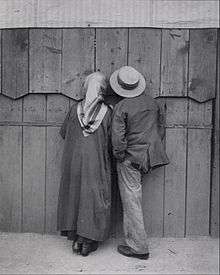

Street photography

Street photography, also sometimes called candid photography, is photography conducted for art or enquiry that features unmediated chance encounters and random incidents[1] within public places. Although there is a difference between street and candid photography, it is usually subtle with most street photography being candid in nature and some candid photography being classifiable as street photography. Street photography does not necessitate the presence of a street or even the urban environment. Though people usually feature directly, street photography might be absent of people and can be of an object or environment where the image projects a decidedly human character in facsimile or aesthetic.[2][3]

Susan Sontag, 1977

The street photographer can be seen as an extension of the flâneur, an observer of the streets (who was often a writer or artist).[4]

Framing and timing can be key aspects of the craft with the aim of some street photography being to create images at a decisive or poignant moment.

Street photography can focus on people and their behavior in public, thereby also recording people's history. This motivation entails having also to navigate or negotiate changing expectations and laws of privacy, security and property. In this respect the street photographer is similar to social documentary photographers or photojournalists who also work in public places, but with the aim of capturing newsworthy events; any of these photographers' images may capture people and property visible within or from public places. The existence of services like Google Street View, recording public space at a massive scale, and the burgeoning trend of self-photography (selfies), further complicate ethical issues reflected in attitudes to street photography.

However, street photography does not need to exclusively feature people within the frame. It can also focus on traces left by humanity that say something about life. Photographers such as William Eggleston often produce street photography where there are no people in the frame, but their presence is suggested by the subject matter.

Much of what is regarded, stylistically and subjectively, as definitive street photography was made in the era spanning the end of the 19th century[5] through to the late 1970s, a period which saw the emergence of portable cameras that enabled candid photography in public places.

History

Depictions of everyday public life form a genre in almost every period of world art, beginning in the pre-historic, Sumerian, Egyptian and early Buddhist art periods. Art dealing with the life of the street, whether within views of cityscapes, or as the dominant motif, appears in the West in the canon of the Northern Renaissance, Baroque, Rococo, of Romanticism, Realism, Impressionism and Post-Impressionism. With the type having been so long established in other media, it followed that photographers would also pursue the subject as soon as technology enabled them.

Nineteenth-century precursors

.jpg)

In 1838 or 1839 the first photograph of figures in the street was recorded by Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre in one of a pair of daguerreotype views taken from his studio window of the Boulevard du Temple in Paris. The second, made at the height of the day, shows an unpopulated stretch of street, while the other was taken at about 8:00 am, and as Beaumont Newhall reports, "The Boulevard, so constantly filled with a moving throng of pedestrians and carriages was perfectly solitary, except an individual who was having his boots brushed. His feet were compelled, of course, to be stationary for some time, one being on the box of the boot black, and the other on the ground. Consequently his boots and legs were well defined, but he is without body or head, because these were in motion."[6]

.jpg)

Charles Nègre was the first photographer to attain the technical sophistication required to register people in movement on the street in Paris in 1851.[7] Photographer John Thomson, a Scotsman working with journalist and social activist Adolphe Smith, published Street Life in London in twelve monthly installments starting in February 1877.[8][9] Thomson played a key role in making everyday life on the streets a significant subject for the medium.[2]

Eugene Atget is regarded as a progenitor, not because he was the first of his kind, but as a result of the popularisation in the late 1920s of his record of Parisian streets by Berenice Abbott, who was inspired to undertake a similar documentation of New York City. As the city developed, Atget helped to promote Parisian streets as a worthy subject for photography. From the 1890s to the 1920s he mainly photographed its architecture, stairs, gardens, and windows. He did photograph some workers, but people were not his main interest.

First sold in 1925, the Leica was the first commercially successful camera to use 35 mm film. Its compactness and bright viewfinder, matched to lenses of quality (changeable on Leicas sold from 1930) helped photographers move through busy streets and capture fleeting moments.[10]

Twentieth-century practitioners

United Kingdom

Paul Martin is considered a pioneer,[5][11] making candid unposed photographs of people in London and at the seaside in the late 19th and early 20th century in order to record life.[11][12] Martin is the first recorded photographer to do so in London with a disguised camera.[11]

Mass-Observation was a social research organisation founded in 1937 which aimed to record everyday life in Britain and to record the reactions of the 'man-in-the-street' to King Edward VIII's abdication in 1936 to marry divorcée Wallis Simpson, and the succession of George VI. Humphrey Spender made photographs on the streets of the northern English industrial town of Bolton, identified for the project's publications as "Yorktown", while filmmaker Humphrey Jennings made a cinematic record in London for a parallel branch of investigation. The chief Mass-Observationists were anthropologist Tom Harrisson in Bolton and poet Charles Madge in London, and their first report was produced as the book "May the Twelfth: Mass-Observation Day-Surveys 1937 by over two hundred observers"[13]

France

The post-war French Humanist School photographers found their subjects on the street or in the bistro. They worked primarily in black‐and‐white in available light with the popular small cameras of the day, discovering what the writer Pierre Mac Orlan (1882–1970) called the "fantastique social de la rue" (social fantastic of the street)[14][15] and their style of image-making rendered romantic and poetic the way of life of ordinary European people, particularly in Paris. Between 1946 and 1957 Le Groupe des XV annually exhibited work of this kind.

Street photography formed the major content of two exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York curated by Edward Steichen, Five French Photographers: Brassai; Cartier-Bresson, Doisneau, Ronis, Izis in 1951 to 1952,[16] and Post-war European Photography in 1953,[17] which exported the concept of street photography internationally. Steichen drew on large numbers of European humanist and American humanistic photographs for his 1955 exhibition The Family of Man, proclaimed as a compassionate portrayal of a global family, which toured the world, inspiring photographers in the depiction of everyday life.

Henri Cartier-Bresson's widely admired Images à la Sauvette (1952)[18] (the English-language edition was titled The Decisive Moment) promoted the idea of taking a picture at what he termed the "decisive moment"; "when form and content, vision and composition merged into a transcendent whole".[19] His book inspired successive generations of photographers to make candid photographs in public places before this approach per se came to be considered déclassé in the aesthetics of postmodernism.[20]

America

Walker Evans[21] worked from 1938 to 1941 on a series in the New York City Subway in order to practice a pure 'record method' of photography; candid portraits of people who would unconsciously come 'into range before an impersonal fixed recording machine during a certain time period'.[22] The recording machine was 'a hidden camera',[23] a 35 mm Contax concealed beneath his coat, that was 'strapped to the chest and connected to a long wire strung down the right sleeve'.[24] However, his work had little contemporary impact as due to Evans' sensitivities about the originality of his project and the privacy of his subjects, it was not published until 1966, in the book Many Are Called,[25] with an introduction written by James Agee in 1940. The work was exhibited as Walker Evans Subway Photographs and Other Recent Acquisitions held at the National Gallery of Art, 1991–1992, accompanied by the catalogue Walker Evans: Subways and Streets.[26]

Helen Levitt, then a teacher of young children, associated with Evans in 1938–39. She documented the transitory chalk drawings that were part of children's street culture in New York at the time, as well as the children who made them. In July 1939, MoMA's new photography section included Levitt's work in its inaugural exhibition.[27] In 1943, Nancy Newhall curated her first solo exhibition Helen Levitt: Photographs of Children there. The photographs were ultimately published in 1987 as In The Street: chalk drawings and messages, New York City 1938–1948.[28]

The beginnings of street photography in the United States can also be linked to those of jazz,[29][30] both emerging as outspoken depictions of everyday life.[31] This connection is visible in the work of the New York school of photography (not to be confused with the New York School). The New York school of photography was not a formal institution, but rather comprised groups of photographers in the mid-20th century based in New York City.

Robert Frank's 1958 book, The Americans, was significant; raw and often out of focus,[32] Frank's images questioned mainstream photography of the time, "challenged all the formal rules laid down by Henri Cartier-Bresson and Walker Evans" and "flew in the face of the wholesome pictorialism and heartfelt photojournalism of American magazines like LIFE and Time".[32] Although the photo-essay format was formative in his early years in Switzerland, Frank rejected it: "I wanted to follow my own intuition and do it my way, and not make any concession – not make a Life story’.[33] Even the work of Cartier-Bresson he regarded as insufficiently subjective: "I’ve always thought it was terribly important to have a point of view, and I was also sort of disappointed in him [Cartier-Bresson] that that was never in his pictures’.[34]

Frank's work thus epitomises the subjectivity of postwar American photography,[30] as John Szarkowski prominently argued; "Minor White’s magazine Aperture and Robert Frank’s book The Americans were characteristic of the new work of their time in the sense that they were both uncompromisingly committed to a highly personal vision of the world".[35] His claim for subjectivism is widely accepted, resulting more recently in Patricia Vettel-Becker's perspective[36] on postwar street photography as highly masculine and centred on the male body, and Lili Corbus Benzer positioning Robert Frank's book as negatively prioritising 'personal vision' over social activism.[37] Mainstream photographers in America fiercely rejected Frank's work, but the book later "changed the nature of photography, what it could say and how it could say it".[32] It was a stepping stone for fresh photographers looking to break away from the restrictions of the old style[2] and "remains perhaps the most influential photography book of the 20th century".[32]

Individual approaches in the later twentieth and early twenty-first centuries

Inspired by Frank, in the 1960s Garry Winogrand, Lee Friedlander and Joel Meyerowitz[38] began photographing on the streets of New York.[19][39] Phil Coomes, writing for BBC News in 2013, said "For those of us interested in street photography there are a few names that stand out and one of those is Garry Winogrand";[40] critic Sean O'Hagan, writing in The Guardian in 2014, said "In the 1960s and 70s, he defined street photography as an attitude as well as a style – and it has laboured in his shadow ever since, so definitive are his photographs of New York."[41]

.jpg)

Returning to the UK in 1965 from the US where he had met Winogrand and adopted street photography, Tony Ray-Jones turned a wry eye on often surreal groupings of British people on their holidays or participating in festivals. The acerbic comic vein of Ray-Jones' high-contrast monochromes, which before his premature death were popularized by Creative Camera (for which he conducted an interview with Brassaï),[42] is mined more recently by Martin Parr in hyper-saturated colour.

Technique

Most kinds of portable camera are used for street photography; for example rangefinders, digital and film SLRs, and point-and-shoot cameras.

The commonly used 35 mm full-frame format focal lengths of 28 mm to 50 mm, are used particularly for their angle of view and increased depth of field, with wide-angle lenses potentially permitting a candid close approach to the human subjects without their suspecting they are in the frame. However, there are no exclusions as to what might be used.

Two commonly used alternative focusing techniques are zone focusing and hyperfocal distance, either to free the photographer from manual-focus; or where autofocus is too slow, or the photographer cannot be sure the focus point will fall where the photographer chooses to place their subject in a quickly changing situation; and which also facilitate shooting "from the hip" i.e. without bringing the camera up to the eye.

With zone focusing, the photographer chooses to set the focus to a specific distance, knowing that a certain area in front of and beyond that point will be in focus. The photographer only has to remember to keep their subject between those set distances.

The hyperfocal distance technique makes as much as possible acceptably sharp so that the photographer is freed up even further, from not having to consider the subject's distance, other than not being too close. The photographer sets the focus to a fixed point particular to the lens focal length, and the chosen aperture, and in the case of digital cameras their crop factor. Thus everything from a specific distance (that will typically be close to the camera), all the way to infinity, will be acceptably sharp. The wider the focal length of the lens (i.e. 28 mm), and the smaller the aperture it is set to (i.e. f/11), and with digital cameras the smaller their crop factor, the closer to the camera is the point at which starts to become acceptably sharp.

Alternatively waist-level finders and the articulating screens of some digital cameras allow for composing, or adjusting focus, without bringing the camera up to the eye and drawing unwanted attention to the photographer.

Anticipation plays a role where a relevant or ironic background that might act as a foil to a foreground incident or passer-by is carefully framed beforehand; it was a strategy much used for early street photographs, most famously in Cartier-Bresson's figure leaping across a puddle in front of a dance poster in Place de l'Europe, Gare Saint Lazare, 1932.

Tony Ray-Jones listed the following shooting advice to himself in his personal journal:[43]

- Be more aggressive

- Get more involved (talk to people)

- Stay with the subject matter (be patient)

- Take simpler pictures

- See if everything in background relates to subject matter

- Vary compositions and angles more

- Be more aware of composition

- Don’t take boring pictures

- Get in closer (use 50mm lens [or possibly ‘less,’ the writing is unclear])

- Watch camera shake (shoot 250 sec or above)

- Don’t shoot too much

- Not all eye level

- No middle distance

Street photography versus documentary photography

Street photography and documentary photography can be very similar genres of photography that often overlap while having distinct individual qualities.

Documentary photographers typically have a defined, premeditated message and an intention to record particular events in history.[44] The gamut of the documentary approach encompasses aspects of journalism, art, education, sociology and history.[45] In social investigation, often documentary images are intended to provoke, or to highlight the need for, societal change. Conversely, street photography is réactive and disinterested by nature[46] and motivated by curiosity or creative inquiry,[47] allowing it to deliver a relatively neutral depiction of the world that mirrors society, "unmanipulated" and with usually unaware subjects.[48]

Candid street photography versus street portraits

Street photography is generally seen as unposed and candid, but there are a few street photographers who will interact with strangers on the streets and take their portraits. Street portraits are classified as portraits taken of strangers in the moment while out doing street photography. They are seen as posed though because there is interaction with the subject.

Legal concerns

The issue of street photographers taking photographs of strangers in public places without their consent (i.e. 'candid photography' by definition) for fine art purposes has been controversial. Photographing people and places in public is legal in most countries protecting freedom of expression and journalistic freedom. There are usually limits on how photos of people may be used and most countries have specific laws regarding people's privacy.

Street photography may also conflict with laws that were originally established to protect against paparazzi, defamation or harassment; and special laws will sometimes apply when taking pictures of minors.

Canada

While the common-law provinces follow the United Kingdom, with respect to the freedom to take pictures in a public place, Quebec law provides that, in most circumstances, their publication can take place only with the consent of the subjects therein.[49]

European Union

The European Union's Human Rights Act 1998, which all EU countries have to uphold in their domestic law, establishes in a right to privacy. This can result in restrictions on the publication of photography.[50] The right to privacy is protected by Article 8 of the convention. In the context of photography, it stands at odds to the Article 10 right of freedom of expression. As such, courts will usually consider the public interest in balancing the rights through the legal test of proportionality.[51]

France

While also limiting photography in order to protect privacy rights, street photography can still be legal in France when pursued as an art form under certain circumstances. While in one prominent case the freedom of artistic expression trumped the individual's right to privacy, the legality will much depend on the individual case.[52]

Germany

Germany protects the right to take photos in public, but also recognizes a "right to one's own picture". That means that even though pictures can often be taken without someones consent, they must not be published without the permission of the person in the picture. The law also protects specifically against defamation”.[53]

This right to one's picture, however, does not extend to people who are not the main focus of the picture (e.g. who just wandered into a scene), or who are not even recognizable in the photo. It also does not usually extend to people who are public figures (e.g. politicians or celebrities).

If a picture is considered art, the courts will also consider the photographer's freedom of artistic expression; meaning that "artful" street photography can still be legally published in certain cases.

Greece

Production, publication and non-commercial sale of street photography is legal in Greece, without the need to have the consent of the shown person or persons. In Greece the right to take photographs and publish them or sell licensing rights over them as fine art or editorial content is protected by the Constitution of Greece (Article 14[54] and other articles) and free speech laws as well as by case law and legal cases. Photographing the police and publishing the photographs is also legal.

Photography and video-taking is also permitted across the whole Athens Metro transport network,[55] which is very popular among Greek street photographers.

Hungary

In Hungary, from 15 March 2014 anyone taking photographs is technically breaking the law if someone wanders into shot, under a new civil code that outlaws taking pictures without the permission of everyone in the photograph. This expands the law on consent to include the taking of photographs, in addition to their publication.[56]

Japan

In Japan permission, or at least signification of intent to photo and the absence of refusal, is needed both for photography and for publication of photos of recognisable people even in public places. 'Hidden photography' (kakushidori hidden, surreptitious photography) 'stolen photography' (nusumitori with no intention of getting permission) and "fast photography' (hayayori before permission and refusal can be given) are forbidden unless in the former permission is obtained from the subject immediately after taking the photo. People have rights to their images (shōzōken, droit de image). The law is especially strict when that which is taken, or the taking, is in any sense shameful. Exception is made for photos of famous people in public places and news photography by registered news media outlets where favour is given to the public right to know.[57]

South Africa

In South Africa, photographing people in public is legal. Reproducing and selling photographs of people is legal for editorial and limited fair use commercial purposes. There exists no case law to define what the limits on commercial use are. Civil law requires the consent of any identifiable persons for advertorial and promotional purposes. Property, including animals, do not enjoy any special consideration.

South Korea

In South Korea, taking pictures of women without their consent, even in public, is considered to be criminal sexual assault, punishable by a fine of under 10 million won and up to 5 years imprisonment.[58] In July 2017 an amendment to the law was voted on in favour of allowing for chemical castration of people taking such photographs.[59]

United Kingdom

The United Kingdom has enacted domestic law in accordance with the Human Rights Act, which limits the publication of certain photographs.[51][60][61]

In terms of photographing property, in general under UK law one cannot prevent photography of private property from a public place, and in general the right to take photographs on private land upon which permission has been obtained is similarly unrestricted. However, landowners are permitted to impose any conditions they wish upon entry to a property, such as forbidding or restricting photography. There are however nuances to these broad principles.

USA

In the US, the protection of free speech is generally interpreted widely, and can include photography.[62]

For example, the case Nussenzweig v. DiCorcia established that taking, publishing and selling street photography (including street portraits) is legal, even without the consent of the person being portrayed, because photography is protected as free speech and art by the First Amendment.[63] However, the Court of Appeals for the State of New York upheld the Nussenzweig decision solely on the basis of the statute of limitations expiring and did not address the free speech and First Amendment arguments.[64]

References

- Warner Marien, Mary (2012). 100 ideas that changed photography. London: Laurence King Publishing. p. 169. ISBN 978-1-85669-793-4.

- Colin Westerbeck. Bystander: A History of Street Photography. 1st ed. Little, Brown and Company, 1994.

- "What is Street Photography?". Retrieved September 22, 2017.

- Sontag, Susan (1978) On Photography. Allen Lane, London p. 55

- Watts, Peter (11 March 2011). "London Street Photography, Museum of London". The Independent. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- Newhall, Beaumont (1982) [First published 1949]. The history of photography from 1839 to the present day (5th ed.). Museum of Modern Art. p. 16. ISBN 978-0-87070-381-2.

- Mora, Gilles (1998). PhotoSPEAK. New York: Abbeville Press. p. 186. ISBN 0-7892-0068-6.

- Thomson, John; Smith, Adolphe (1969) [First published in 1877]. Street life in London. New York: Benjamin Blom. p. Publisher's Note. OCLC 558085267.

- Abbott, Brett (2010). Engaged observers: Documentary photography since the sixties. J. Paul Getty Museum. p. 4. ISBN 978-1-60606-022-3.

- Michael Pritchard, "Leica I–III models", pp. 358–359 of Robin Lenman, ed., The Oxford Companion to the Photograph (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005; ISBN 978-0-19-866271-6).

- "London street photography through the decades". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- McDonald, Sarah. "The hidden Camera" (PDF). Getty Images. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- Jennings, Humphrey (1937). May the twelfth : Mass-Observation day-surveys, 1937. Faber and Faber. Retrieved 22 March 2016.

- In the unpaginated introduction to Kertész, A., & MacOrlan, P. (1934). Paris: Vu par André Kertész. Paris: Librarie Plon.

- Thézy, Marie de; Nori, Claude (1992), La photographie humaniste : 1930-1960, histoire d'un mouvement en France, Contrejour, ISBN 978-2-85949-145-1

- "For a contemporary review see Jacob Deschin, 'The Work of French Photographers', The New York Times (23 December 1951), X14. The U.S. Camera Annual 1953 which includes a selection of photographs from the exhibition under the revised title, Four French Photographers: Brassai, Doisneau, Ronis, Izis (because he could not be contacted by time of publication, Cartier-Bresson was omitted) Kristen Gresh (2005) The European roots of The Family of Man, History of Photography, 29:4, 331-343, DOI: 10.1080/03087298.2005.10442815

- Jacob Deschin, 'European Pictures: Modern Museum Presents Collection by Steichen', The New York Times (31 May 1953), X13; US. Camera Annual 1954, ed. Tom Maloney, New York: U.S. Camera Publishing Co. 1953.

- Cartier-Bresson, Henri (1952). Images a la sauvette : photograhies par Henri Cartier-Bresson. Éditions Verve. Retrieved 21 March 2016.

- O'Hagan, Sean (18 April 2010). "Why street photography is facing a moment of truth". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- Jobey, Liz (15 August 2014). "Street photography". Financial Times. London. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- Judith Keller (1993) "Walker Evans and many are called", History of Photography, 17:2, 152-165, DOI: 10.1080/03087298.1993.10442613

- See Evans's manuscript in the Getty Museum collection (JPGM 84.xG.953.50.2), 'Unposed photographic records of people', first published in Walker Evans at Work, New York: Harper and Row 1982, 160.

- Walker Evans, 'The unposed portrait', Harper's Bazaar 95 (March 1962), 120-5, in Greenough, Walker Evans, 127.

- Walker Evans, 'Twenty thousand moments under Lexington Avenue: A superfluous word', unpublished draft, Greenough, Walker Evans, 127.

- Evans, Walker; Agee, James; Sante, Luc; Rosenheim, Jeff L; Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) (2004). Many are called (First Metropolitan Museum of Art/Yale University Press ed.). New Haven Yale University Press New York Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-300-10617-6.

- Greenough, Sarah; Evans, Walker, 1903-1975; National Gallery of Art (U.S.) (1991). Walker Evans subways and streets. National Gallery of Art. ISBN 978-0-89468-166-0.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Hopkinson, Amanda (April 3, 2009). "Obituary - Helen Levitt: Award-winning New York photographer noted for street scenes and social realism". The Guardian.

- Hambourg, Maria Morris (1991). "Helen Levitt: A Life in Part". In Phillips, Sandra S. (ed.). Helen Levitt. San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. pp. 45–63. ISBN 0-918471-22-2.

- "When discussing his work. [Roy] DeCarava confronts the dilemma of categorization:'The major definition has been that I am a documentary photographer, and then…I became a people's photographer, and then I became a street photographer, and then I became a jazz photographer, and oh, yes. I musn’t forget, I am a black photographer...and there is nothing wrong with any of those definitions. The only trouble is that I need all of them to define myself. Warren, Lynne; Warren, Lynn (2005), Encyclopedia of Twentieth-Century Photography, 3-Volume Set, Taylor and Francis, p. 371, ISBN 978-0-203-94338-0

- Mortenson, E. (2014). The Ghost of Humanism: Rethinking the Subjective Turn in Postwar American Photography. History of Photography, 38(4), 418-434.

- Abbott, Brett; J. Paul Getty Museum (2010), Engaged observers : documentary photography since the sixties, J. Paul Getty Museum, p. 16, ISBN 978-1-60606-022-3

- O'Hagan, Sean (7 November 2014). "Robert Frank at 90: the photographer who revealed America won't look back". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ‘Robert Frank’, in Photography Within the Humanities, ed. Eugenia Parry Janis and Wendy MacNeil, Danbury, NH: Addison House 1977, quoted in Bezner, Photography and Politics in America, 179.

- Photography Within the Humanities, ed. Janis and MacNeil, 56, quoted in James Guimond, American Photography and the American Dream, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press 1991, 242.

- Szarkowski, John; Museum of Modern Art (New York, N.Y.); New York Graphic Society (1978), Mirrors and windows : American photography since 1960, Museum of Modern Art, pp. 17–18, ISBN 978-0-87070-476-5

- Vettel-Becker, Patricia (2005), Shooting from the hip : photography, masculinity, and postwar America, University of Minnesota Press, ISBN 978-0-8166-4301-1

- Bezner, Lili Corbus (1999), Photography and politics in America : from the New Deal into the Cold War, Johns Hopkins University Press ; Wantage : University Presses Marketing, ISBN 978-0-8018-6187-1

- O'Hagan, Sean (8 March 2011). "Right Here, Right Now: Photography snatched off the streets". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- Jobey, Liz (10 February 2012). "Paul Graham: 'The Present'". Financial Times. London. Retrieved 28 April 2015.

- Coomes, Phil (11 March 2013). "The photographic legacy of Garry Winogrand". BBC News. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- O'Hagan, Sean (15 October 2014). "Garry Winogrand: The restless genius who gave street photography attitude". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- 'Brassai talking about photography: An interview with Tony Ray-Jones', Creative Camera, April 1970, p. 120.

- Ray-Jones' archive, National Media Museum, Bradford, England and exhibited by them in the touring exhibition Only in England in 2015

- Newhall, "Documentary Approach to Photography", Parnassus 10, no. 3 (March 1938): pp. 2–6. 22

- Becker, Karin E (1980). Dorothea Lange and the documentary tradition. Louisiana State University Press. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-8071-0551-1.

- Gleason, T. R. (2008). "The communicative roles of street and social landscape photography". SIMILE: Stud. Media Infor. Literacy Educ, 8(4), 1-13.

- Jordan, S. (2016). 12 "Interrupting the Street. Cities Interrupted": Visual Culture and Urban Space, 193.

- Gleason, Timothy. "The Communicative Roles of Street and Social Landscape Photography". Simile vol. 8, no. 4 (n.d.): 1–13.

- Aubry v Éditions Vice-Versa Inc 1998 CanLII 817 at par. 55–59, [1998] 1 SCR 591 (9 April 1998)

- Human Rights Act 1998 sections 2 & 3

- Mosley v News Group Newspapers Ltd [2008] EWHC 1777 (QB)

- Laurent, Olivier (23 April 2013). "Protecting the Right to Photograph, or Not to Be Photographed". The New York Times. Retrieved 15 February 2015.

- "Watch Out!". 21 August 2015.

- "Σύνταγμα".

- "synigoros.gr" (PDF).

- Nolan, Daniel (14 March 2014). "Hungary law requires photographers to ask permission to take pictures". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 May 2014.

- Murakami, Takashi (2000). "肖像権とその周辺 : 写真の撮影・公表をめぐる法律問題と判例の展開" [Study on the Rules for taking a Photograph of a Person and its Publication in Japan] (PDF). Journal of Law and Politics (in Japanese). 39: 25–112. ISSN 0915-0463. Retrieved 2016-12-07.

- "South Korean law on criminal sexual assault, Chapter 1 Article 14"

- "Court legalizes chemical castration of men convicted of photography related sexual assault", edaily

- Campbell v Mirror Group Newspapers Ltd [2004] UKHL 22

- Murray v Express Newspapers Plc [2008] EWCA Civ 446

- Bill, Kenworthy. "Photography & the First Amendment". First Amendment Center.

- "Nussenzweig v. DiCorcia". New York Supreme Court. Retrieved 2011-12-05.

- "Nussenzweig v. Philip-Lorca, 9 N.Y.3d 184 | Casetext". casetext.com. Retrieved 2019-08-13.

Further reading

- Bystander: A History of Street Photography by Joel Meyerowitz and Colin Westerbeck, Boston: Bulfinch Press, 1994. ISBN 0-82121-755-0. Boston: Bulfinch Press, 2001. ISBN 9780821227268.

- The Sidewalk Never Ends: Street Photography Since the 1970s by Colin Westerbeck, Chicago: Art Institute of Chicago, 2001.

- Street Photography Now by Sophie Howarth and Stephen McLaren, London: Thames & Hudson, 2010. ISBN 978-0-500-54393-1 .

- 10 – 10 years of In-Public. London: Nick Turpin, 2010. ISBN 978-0-9563322-1-9 .

- The Street Photographer's Manual. London: Thames & Hudson, 2014. ISBN 978-0-500-29130-6. By David Gibson.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Street photography. |

- Worldwide Photographer's Rights – privacy laws in many countries in regard to street photography

- Legal Rights of Photographers in the US by Andrew Kantor

- UK Photographers Rights Guide v2 by Linda Macpherson