Nubian pyramids

Nubian pyramids are pyramids that were built by the rulers of the ancient Kushite kingdoms. The area of the Nile valley known as Nubia, which lies within the north of present day Sudan, was home to three Kushite kingdoms during antiquity. The first had its capital at Kerma (2500–1500 BC). The second was centered on Napata (1000–300 BC). Finally, the last kingdom was centered on Meroë (300 BC–AD 300). They are built of granite and sandstone. The pyramids were partially demolished by Italian treasure hunter Giuseppe Ferlini in the 1830s.[1]

Aerial view of the pyramids of Meroë | |

Location of Nubian pyramids | |

| Alternative name | Nubian pyramids |

|---|---|

| Location | Sudan |

| Type | Pyramids |

| History | |

| Founded | 800 BCE - 100 CE |

Kerma was Nubia's first centralized state with its own indigenous forms of architecture and burial customs. The last two kingdoms, Napata and Meroë, were heavily influenced by ancient Egypt culturally, economically, politically, and militarily. The Kushite kingdoms in turn competed strongly with Egypt economically and militarily. In 728 BC, the Kushite king Piye united the entire Nile valley from the delta to the city of Napata under his rule. Piye and his descendants ruled as the pharaohs of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty. Napatan control of Egypt ended after being conquered by Assyria in 656 BC. The Nubian pyramids are recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[2]

Pyramids

So far, more than 35 pyramids[3] grouped in five sites were discovered in Sudan. They were constructed in Nubia over a period of a few hundred years to serve as tombs for the kings and queens and wealthy citizens of Napata and Meroë.

The first three sites are located around Napata in Lower Nubia, near the modern town of Karima.

The first of these was built at the site of el-Kurru, including the tombs of King Kashta and his son Piye, together with Piye's successors Shabaka, Shabataka, and Tanwetamani. Fourteen pyramids were constructed for their queens, several of whom were renowned warrior queens. This can be compared to approximately 120 much larger pyramids that were constructed in Ancient Egypt over a period of 3000 years.

Later Napatan pyramids were sited at Nuri, 10 km north on the opposite bank of the Nile. This necropolis was the burial place of 21 kings and 52 queens and princes including Anlami and Aspelta. The bodies of these kings were placed in huge granite sarcophagi. Aspelta's weighed 15.5 tons, and its lid weighed four tons.[4] The oldest and largest pyramid at Nuri is that of the Napatan king and Twenty-fifth Dynasty pharaoh Taharqa.

.jpg)

Another small group of 9 pyramids is located next to Jebel Barkal itself.

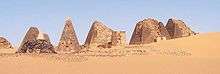

The most extensive Nubian pyramid site is at Meroë, which is located between the fifth and sixth cataracts of the Nile, approximately 240 kilometres (150 mi) north of Khartoum. During the Meroitic period, over forty queens and kings were buried there.

Between 2009 and 2012 the new group of pyramids was discovered near the village Sedeinga.

The physical proportions of Nubian pyramids differ markedly from the Egyptian edifices: they are built of stepped courses of horizontally positioned stone blocks and range approximately 6–30 metres (20–98 ft) in height, but rise from fairly small foundation footprints that rarely exceed 8 metres (26 ft) in width, resulting in tall, narrow structures inclined at approximately 70°. Most also have offering temple structures abutting their base with unique Kushite characteristics. By comparison, Egyptian pyramids of similar height generally had foundation footprints that were at least five times larger and were inclined at angles between 40–50°.

.jpg)

The tombs inside the pyramids of Nubia were plundered in ancient times. Wall reliefs preserved in the tomb chapels reveal that their royal occupants were mummified, covered with jewellery and laid to rest in wooden mummy cases. At the time of their exploration by archaeologists in the 19th and 20th centuries, some pyramids were found to contain the remains of bows, quivers of arrows, archers' thumb rings, horse harnesses, wooden boxes, furniture, pottery, colored glass, metal vessels, and many other artefacts attesting to extensive Meroitic trade with Egypt and the Hellenistic world.

A pyramid excavated at Meroë included hundreds of heavy items such as large blocks decorated with rock art and 390 stones that comprised the pyramid. A cow buried complete with eye ointment was also unearthed in the area to be flooded by the Meroë Dam, as were ringing rocks that were tapped to create a melodic sound.[5]

In the 1830s Giuseppe Ferlini came to Meroe seeking treasure and raided and demolished a number of pyramids which had been found “in good conditions” by Frédéric Cailliaud just a few years earlier.[6] At Wad ban Naqa, he leveled the pyramid N6 of the kandake Amanishakheto starting from the top, and finally found her treasure composed of dozens of gold and silver jewelry pieces. Overall, he is considered responsible for the destruction of over 40 pyramids.[6][7]

Having found the treasure he was looking for, in 1836 Ferlini returned home.[8] A year later he wrote a report of his expedition containing a catalog of his findings, which was translated in French and republished in 1838.[note 1][9] He tried to sell the treasure, but at this time nobody believed that such high quality jewellery could be made in Black Africa. His finds were finally sold in Germany: part of these were purchased by king Ludwig I of Bavaria and are now in the State Museum of Egyptian Art of Munich, while the remaining – under suggestions of Karl Richard Lepsius and of Christian Charles Josias von Bunsen – was bought by the Egyptian Museum of Berlin where it still is.[6]

George Reisner, a Harvard archaeologist, investigated the pyramids at Nuri and mapped more than 80 royal Kushite burials in 1916-1919.[10] Reisner started to explore burial chambers but he found they were flooded caused by rising water table. He abandoned further excavation because he thought it was too dangerous, probably because a collapse of a staircase had killed five of his workers.[10] Some of his findings were published in 1955.[11]

National Geographic funded explorations from 2015-2019 using underwater scuba diving equipment[12] and remote controlled robots.[13]

Pyramids and cemeteries

- The royal cemetery at el-Kurru. Kashta, Piye, Tantamani, Shabaka and several queens are buried in pyramids at El-Kurru.

- The Pyramids of Meroe (Begarawiyah). Dating to the Meroitic period. Pyramids date from ca. 720–300 BC at the South Cemetery and ca. 300 BC to about 350 AD at the North Cemetery.

- The royal cemetery at Nuri. Kings Taharqa, Atlanersa and other royals from the kingdom of Napata are buried at Nuri.

- Pyramids of Gebel Barkal

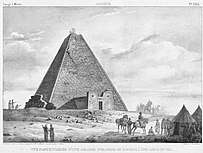

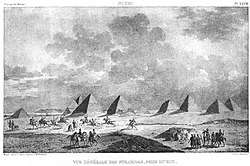

Pyramids of Meroe (Begarawiyah) in 1821

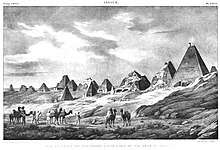

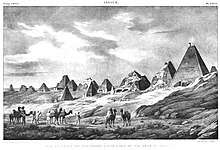

Pyramids of Meroe (Begarawiyah) in 1821 Pyramids of Nuri in 1821

Pyramids of Nuri in 1821 Pyramids at Jebel Barkal in 1821

Pyramids at Jebel Barkal in 1821

See also

- Ancient Egypt

- Candace of Meroë

- Kingdom of Kush

- List of megalithic sites

- Meroë

- Nubia

- Nubian architecture

- Sedeinga pyramids

Notes

- Giuseppe Ferlini, Relation Historique des Fouilles Operées dans la Nubia par le docteur Joseph Ferlini de Bologna, suivie d'un catalogue des objets qu'il a trouvés dans l'une des quarante-sept pyramides aux environs de l'ancienne ville de Meroe, et d'une description des grands déserts de Coruscah et de Sinnaar. Rome, 1838.

References

- Melikian, Souren (2010-05-21). "The Mysteries of Meroe". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-04-16.

- "Wonder at the Meroe Pyramids, Forgotten Relics of the Ancient World". Atlas Obscura. 2017-05-03. Retrieved 2017-07-31.

- Cluster of 35 Ancient Pyramids and Graves Discovered in Sudan

- Lehner, Mark (1997). The Complete Pyramids. Thames and Hudson. pp. 196–197. ISBN 978-0-500-05084-2.

- Adams, Stephen (16 October 2008). "Ancient Egypt had powerful Sudan rival, British Museum dig shows". The Telegraph.

- Cimmino, Franco (1996). Storia delle Piramidi (in Italian). Milano: Rusconi. ISBN 88-18-70143-6., pp. 416-7

- Welsby, Derek A. (1998). The kingdom of Kush: the Napatan and Meroitic empire. Princeton, New Jersey: Markus Wiener., pp. 86; 185

- Epitaph from his gravestone in the Certosa di Bologna.

- Dawson, Warren R.; Uphill, Eric P. (1972). Who Was Who in Egyptology. London: Harrison & sons., p. 166

- Emberling, Geoff (2014-04-04). "Continuing Excavations at an Ancient Burial Site Last Touched in 1919". National Geographic Society Newsroom. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- Romey, Kristin (2019-07-02). "Dive beneath the pyramids of Egypt's black pharaohs". National Geographic, Culture & History. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- Gwin, Peter; Romey, Kirstin (2019-07-02). "Episode 4: Scuba diving in a pyramid". National Geographic. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

- Rappaport, Nora (2015-05-21). "Amazing Drone Footage of Nubian Pyramids". National Geographic Society Newsroom. Retrieved 2019-07-04.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nubian pyramids. |

- Pyramids of Nubia – A site detailing the three major pyramid sites of ancient Nubia

- Nubian Pyramids – A site featuring numerous photographs of the pyramids at Meroë

- Aerial Photographs of Sudan – A site featuring spectacular aerial photographs of the pyramids and temples at el-Kurru, Nuri, and Meroë

- Aerial video of Nubia Pyramids

- Voyage au pays des pharaons noirs Travel in Sudan and notes on Nubian history (in French)