Pakistani Americans

Pakistani Americans (Urdu: پاکستانی نژاد امریکی) are Americans whose ancestry originates from Pakistan or Pakistanis who migrated to and reside in the United States. The term may also refer to people who hold a dual Pakistani and U.S. citizenship. Educational attainment level and household income are much higher in the Pakistani-American diaspora in comparison to the general U.S. population.[2] There are an estimated 518,116 self-identified Pakistani Americans, representing about 0.157% of the U.S. population.[1]

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 508,116 U.S. Estimate, 2018, self-reported[1] Around 0.157% of the U.S. population | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| New York City Metropolitan Area, New Jersey, Baltimore-Washington Metropolitan Area, Philadelphia metropolitan area, Chicago Metropolitan Area, Houston metropolitan area, Los Angeles Metropolitan Area, San Francisco Bay Area, Boston, Atlanta, Phoenix metropolitan area, Dallas-Fort Worth, Florida, and major metropolitan areas throughout the United States | |

| Languages | |

| Religion | |

Predominantly Sunni Islam

| |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Pakistani Canadians, British Pakistanis, Overseas Pakistani |

History in the United States

Immigrants from areas that are now part of Pakistan (formerly northwestern colonial India) had been migrating to America as early as the eighteenth century, working in agriculture, logging, and mining in the western states of California, Oregon, and Washington.[3] The passage of the Luce–Celler Act of 1946 allowed these immigrants to acquire U.S. citizenship through naturalization. Between 1947 and 1965, only 2,500 Pakistani immigrants entered the United States; most of them were students who chose to settle in the United States after graduating from American universities, according to reports from the U.S. Immigration and Naturalization Service. This marked the beginning of a distinct 'Pakistani' community in America. However, after President Lyndon Johnson signed the INS Act of 1965 into law, eliminating per-country immigration quotas and introducing immigration on the basis of professional experience and education, the number of Pakistanis immigrating to the United States increased dramatically.[4] By 1990, the United States Census Bureau indicated that there were about 100,000 Pakistani Americans in the United States and by 2005 their population had grown to 210,000.[5]

Ethnic classification

Pakistani Americans are classified as Asian Americans by the U.S. Census Bureau. Geographically, they are South Asian American.

Demographics

The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that there were 508,116 U.S. residents of Pakistani descent living in the United States in 2018.[1] This is up 24.18% from the number of people who reported as such in the 2010 United States Census, which was 409,163.[7] Some studies estimate the size of the Pakistani community to be much higher and in 2005 research by the Pakistani embassy in the US found that the population numbered more than 700,000 people.[8][9] Pakistan is the 12th highest ranked source country for immigration into the United States.[10]

About half of Pakistani Americans are Muhajirs, about 30% have origins in the Punjab Province of Pakistan, and the rest are made up of other ethnic Groups from Pakistan, including Pashtuns, Balochis, Sindhis, Memons, and Kashmiris.[11] The most systematic study of the demography of Pakistanis in America is found in Prof. Adil Najam's book 'Portrait of a Giving Community', which estimates a total of around 500,000.[12]

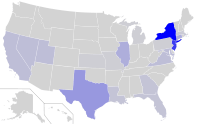

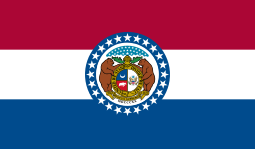

By state totals

This is a list of all 50 states in the U.S. and the District of Columbia ordered by the total estimated population claiming origin from Pakistan according to the 2018 American Community Survey.[1]

.svg.png)

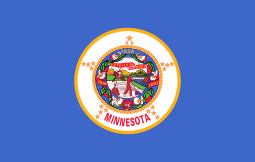

By state concentration

This is a list of all 50 states in the U.S. and the District of Columbia ordered by the estimated concentration of the population claiming origin from Pakistan according to the 2018 American Community Survey rounded to the nearest thousandth of a percent.[1]

.svg.png)

New York City Metropolitan Area

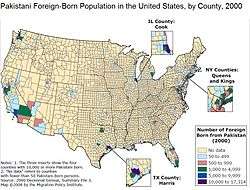

The Greater New York City Combined Statistical Area, consisting of New York City, Long Island, and adjacent areas within New York State, as well as nearby areas within the states of New Jersey (extending to Trenton), Connecticut (extending to Bridgeport), and including Pike County, Pennsylvania, comprises by far the largest Pakistani American population of any metropolitan area in the United States, receiving the highest legal permanent resident Pakistani immigrant population.[13] Within the greater metropolitan area, New York City itself hosts the largest concentration of Pakistani Americans of any U.S. city proper, with a population of approximately 34,310 as of the 2000 United States Census, primarily in the boroughs of Queens and Brooklyn.[14] These numbers made Pakistani Americans the fifth largest Asian American group in New York City. As of 2006, this number had increased to 60,000 people of Pakistani descent said to be living in New York City. This figure additionally rises to a number between 70,000 when illegal immigrants are also included.[15] Pakistan International Airlines served John F. Kennedy International Airport in Queens until 2017.[16] While New York City has celebrated North America's largest Pakistan Day parade for decades, New Jersey's first annual Pakistan Day parade was held on August 16, 2015, in Edison and Woodbridge, New Jersey.[17][18]

California

Silicon Valley counts highly educated and skilled workers from Pakistan most of whom work in the Information Technology, software development, and computer science sectors, and it has been estimated that some 10,000 Pakistanis work in the Silicon Valley.[19] From 1990 - 2000 the Pakistani population in the San Francisco Bay Area increased to 6,119 which is an increase of 76%.[20]

Historically pre-dating the modern state of Pakistan, Muslims from the British Raj immigrated in waves starting in 1902 to the west coast, most notably in Yuba City, California, in search of jobs in mining and logging. Some of the oldest American Muslim communities, and largest Sikh ones in America, exist in Yuba City today.

Chicago

Devon Avenue has a street named after the founder of Pakistan Muhammad Ali Jinnah as well as Mahatma Gandhi to accommodate both the Indian and Pakistani business there.[4][21]

Texas

There is a large Pakistani population in Texas with estimates numbered around 50,000. They are primarily concentrated around the metropolitan areas of Austin, Dallas and Houston (in the three County areas of Harris, Montgomery and Fort Bend).[22]

The community is made up of professionals involved in medicine, IT, engineering, large businesses involved in textiles, manufacturing, real estate, management and also smaller ones such as travel agencies, motels, restaurants, convenience stores and gas stations.[23]

Other cities

Newly arrived Pakistani immigrants mostly settle in cities like New York City, Paterson, New Jersey, Los Angeles, Boston, San Diego, San Francisco, Chicago, Denver and Detroit;[24] like other South Asians, Pakistanis settle in major urban areas. The Pakistani American community are also prevalent in Arizona, Arkansas, Cleveland, Colorado, Connecticut, Louisiana, Massachusetts, Michigan, Nevada, New England, New Mexico, Oklahoma, Oregon, Seattle, Virginia, Washington, D.C., Wisconsin and Utah.[12][23][25][26] Fremont, California has the most Pashtuns in the United States, with many of them emigrating from Pakistan.

Towns and cities in America with the highest percentage of Pakistani ancestry include Madison Park, New Jersey (5.7%),[27] Herricks, New York (4.1% ),[27] Boonton, New Jersey (4%),[28] Lincolnia, Virginia (3%),[29] Stafford, Texas (2%)[30] and Avenel, New Jersey (2%).[31]

For a more comprehensive list, see Epodunk - Pakistani Ancestry by place and Cities with the most residents born in Pakistan== US Census Data === According to the 2010 US Census here are the number of Pakistani Households in the following US Counties.

| County | Pakistani Households | County Population | Concentration of Pakistanis |

| Queens County, New York | 15,972 | 2,296,000 | 3.5% |

| Kings County, New York | 14,412 | 2,592,000 | 2.8% |

| Cook County, Illinois | 12,759 | 5,241,000 | 1.2% |

| Harris County, Texas | 11,221 | 4,337,000 | 1.3% |

| Fairfax County, Virginia | 7,358 | 1,131,000 | 3.3% |

| Los Angeles County, California | 7,025 | 10,020,000 | 0.4% |

| DuPage County, Illinois | 4,000 | 932,126 | 2.1% |

| Middlesex County, New Jersey | 3,788 | 828,919 | 2.3% |

| Orange County, California | 3,658 | 3,114,000 | 0.6% |

| Dallas County, Texas | 3,627 | 2,480,000 | 0.7% |

| Hudson County, New Jersey | 3,369 | 660,282 | 2.6% |

| Fort Bend County, Texas (Sugar Land) | 3,216 | 652,365 | 2.5% |

| Nassau County, New York | 3,137 | 1,352,000 | 1.2% |

| Santa Clara County, California | 2,824 | 1,862,000 | 0.8% |

| Alameda County, California | 2,726 | 1,579,000 | 0.9% |

| Montgomery County, Maryland | 2,410 | 1,017,000 | 1.2% |

| Tarrant County, Texas | 2,388 | 1,912,000 | 0.6% |

| Miami-Dade County, Florida | 2,038 | 2,617,000 | 0.4% |

| Broward County, Florida | 1,934 | 1,839,000 | 0.5% |

| Gwinnett County, Georgia | 1,712 | 859,304 | 1.0% |

| Bergen County, New Jersey | 1,532 | 925,328 | 0.8% |

| Baltimore County, Maryland | 1,226 | 823,015 | 0.7% |

| Contra Costa County, California | 1,148 | 1,094,000 | 0.5% |

| Collin County, Texas (Plano) | 1,015 | 854,778 | 0.6% |

| Essex County, New Jersey | 792 | 789,565 | 0.5% |

| Montgomery County, Texas | 769 | 499,137 | 0.8% |

| Howard County, Maryland | 678 | 304,580 | 1.1% |

| Cobb County, Georgia | 663 | 717,190 | 0.5% |

| Dekalb County, Georgia | 587 | 713,340 | 0.4% |

| Will County, Illinois | 554 | 682,829 | 0.4% |

| Fulton County, Georgia | 491 | 984,293 | 0.2% |

| Palm Beach, County Florida | 472 | 1,372,000 | 0.2% |

| Forsyth County, Georgia | 287 | 195,405 | 0.7% |

From the above list provided by the US Census 2010 data the following Metropolitan List has been compiled.

| Metropolitan Area | Pakistani Households |

| New York City | 39,865 |

| Chicago | 17,313 |

| Houston | 15,206 |

| DC-VA-MD Tri-State Area | 11,672 |

| Los Angeles | 10,683 |

| Dallas/Fort Worth | 7,061 |

| San Francisco/San Jose | 6,698 |

| Miami-Fort Lauderdale | 4,444 |

| Atlanta | 3,740 |

Culture

Like the terms "Asian American" or "South Asian American", the term "Pakistani American" is also an umbrella label applying to a variety of views, values, lifestyles, and appearances. Although Pakistani Americans retain a strong ethnic identity, they are known to assimilate into American culture while at the same time keeping the culture of their ancestors. Pakistani Americans are known to assimilate more easily than many other immigrant groups because they have fewer language barriers (English is the official language of Pakistan and widely spoken in the country among professional classes), more educational credentials (immigrants are disproportionately well educated among Pakistanis), and come from a similarly diverse, relatively tolerant, and multi-ethnic society. Many Pakistani Americans tend to associate themselves with Iranic cultures (Pashtun & Balochi) or Punjabi culture.

Pakistani Americans are well represented in the fields of medicine, engineering, finance and information technology. Pakistani Americans have brought Pakistani cuisine to the United States, and Pakistani cuisine has been established as one of the most popular cuisines in the country with hundreds of Pakistani restaurants in each major city and several similar eateries in smaller cities and towns. There are many Pakistani markets and stores in the United States. Many of such establishments cater to a broader South Asian audience due to the lack of differences in cuisine. Some of the largest Pakistani markets are in New York City, Central New Jersey, Washington, D.C., Chicago, and Houston.

Languages

Pakistani Americans often retain their native languages, such as Urdu.[32] As English is the official language in Pakistan and is taught in schools throughout the country, many immigrants coming to the United States generally have a good native fluency for the English language.[33]

Many Pakistanis in the United States speak some of Pakistan's various regional languages such as Punjabi, Saraiki, Sindhi, Balochi, Pashto and Kashmiri.

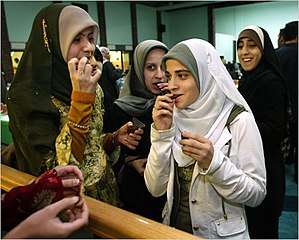

Religion

Most Pakistani Americans are Muslims. Religion figures prominently in many Pakistani American families.

The majority of Pakistanis belong to the Sunni sect of Islam, although there is a significant representation of the Shi'ite and Ahmadiyya sects. In smaller towns in America where there may not be mosques within easy access, Pakistani Americans make trips to attend the nearest one on major religious holidays and occasions.[11] Pakistani Americans worship at mosques alongside other Muslims who might trace their ancestry to all parts of the Islamic world; there are generally no separate Pakistani American mosques.

Pakistani Americans also participate in and contribute to the larger Islamic community, which includes Arab Americans, Iranian American, Turkish American, African Americans, Indonesian Americans, Malaysian Americans, South Asian Americans, and many more ethnic backgrounds in America.[11] They are part of the larger community's efforts to educate the country about the ideals of Islam and the teachings of Mohammed. Pakistani Americans have played important roles in the association the Muslim Students of America (MSA), which caters to the needs of Islamic students across the United States.[11]

Although most Pakistani Americans are Muslims, there are also Hindus, Christians, and Zoroastrians within the community. Pakistani Christians, like Asian Christians, worship at churches all over the country and share in the religious life of the dominant Christian culture in America. Pakistani Hindus mainly share in the religious life of numerous Hindus from various nationalities, such as Indian American Hindus. Pakistani Hindus are mostly from Karachi. In recent times, Pakistani Zoroastrians (called Parsis) have come to the United States mainly from the cities of Lahore and Karachi. Apart from fellow Pakistanis, they also congregate with fellow Zoroastrian co-religionists from Iran.

Music

Notable contributions

Pakistani Americans have made many contributions to the United States in many fields, such as science, politics, military, sports, philanthropy, business and economy.

Business and finance

Shahid Khan is a Pakistani American billionaire businessman who is owner of an auto-parts company and an NFL team Jacksonville Jaguars. As of 2012, he was estimated to have a net worth exceeding $6 billion and is featured on the Forbes 400 list of richest Americans, on which he ranks 179.[34] Overall on the Forbes list of billionaires, he is the 491st richest person in the world.[35]

Philanthropy

The Pakistani American community is said to be philanthropic, research shows that in the year 2002 the community gave close to US$1 Billion in philanthropic activities (including value of volunteered time).[36] Since the Pakistani diaspora has spread internationally over the years, many Pakistanis living abroad choose to donate time, money and talent to further development in Pakistan. Pakathon, for example, aims to empower Pakistanis through innovation, technology and entrepreneurship.

Pakistani-American business tycoon and Philanthropist, Syed Javaid Anwar, from Midland Texas raised by his late mother Ms. Tahira Khatoon (12/22/1928 – 3/21/2015),[37] has shown great excellence as a global citizen as shown by his commitment to many organizations including Habitat for Humanity, University of Texas at Austin, Permian Basin Chapter of the Association of Fundraising Professionals, The Human Development Foundation, and lastly the Pakistani Chamber of Commerce.[38][39]

Military

Pakistani American soldiers make up a sizable proportion of the over 4,000 Muslim service members in the US military.[40] As of February 2008, 125 Pakistan-born service members were on active duty in the US Armed Forces, out of the 826 US service members born in South-Central Asia. This figure refers to those who were naturalized with US citizenship and does not include US-born service members of Pakistani ancestry.[41]

Pakistani American service members have assisted with US intelligence operations, and worked as interpreters, interrogators and liaison officers in Afghanistan. Their knowledge of local languages such as Pashto and Dari gives them an edge in coordination activities.[42]

The overall number of Afghan and Pakistani Americans involved in the war effort has not been released, although their recruitment by the CIA and U.S. Defense Department agencies has been very public. Because most of their work was secret, few of the men have received any public recognition.

— Los Angeles Times[42]

- Pakistani American marine Lieutenant Colonel Asad A. Khan was part of the first conventional units to enter into Afghanistan in late 2001.[42] Khan would return to Afghanistan in command of 1st Battalion 6th Marines in 2004;[43][44] only to be later relieved of command.[44][45]

- Cpt. Humayun Saqib Muazzam Khan was a Pakistani American soldier who posthumously received the Bronze Star and Purple Heart military decorations. He was killed in Iraq and buried at the Arlington National Cemetery.[46][47] Khan's parents, Khizr and Ghazala Khan, appeared at the 2016 Democratic National Convention to challenge Donald Trump's views on Muslims.[48]

- Another Pakistani American who received both a Bronze Star and Purple Heart was Kareem Rashad Sultan Khan who died in Iraq.[49] Others have served in different capacities, such as working as military commissaries abroad.[50]

- Sgt. Wasim Khan was wounded in action during Operation Iraqi Freedom, June 2003, when his leg was shattered by an RPG attack.[51] He is a native of Gilgit in northern Pakistan[52] and migrated to the US with his family in 1997. In 1998, he joined the US Army and was deployed to Iraq with the 2/3 Field Artillery Battalion. He has been awarded numerous military decorations.[53] He was invited as a guest by former President George Bush.

- Spc. Azhar Ali was a Pakistani-American soldier who was also killed while by a roadside bomb while in service in Baghdad, Iraq. He joined the military in 1998, in the 69th Regiment of New York. He was buried at the Flushing Cemetery.[54]

- Commander Muhammad Muzzafar F. Khan is the first Pakistani American to take command of an operational aviation squadron in the U.S. Navy. He commands the Sea Control "Topcats" Squadron.[55]

- Pfc. Usman Khattak, an ethnic Pashtun hailing from northwest Pakistan, is a US Army Food Specialist with the 539th Transportation Division and is based at the US Army camp in Kuwait.[56]

- Sgt. Fahad Kamal is a combat medic in the Army and has served in Afghanistan.[40]

- 2d Lt. Mohsin Naqvi was killed in Afghanistan while on patrol duty. A resident of Newburgh, New York, he enlisted in the Army Reserve a few days after the September 11 attacks and had also previously served in Iraq. He was paid tribute by the Pakistani American community[57] and received a Purple Heart and Bronze Star.[49]

- Naveed Jamali is an intelligence officer in the United States Navy Reserve.[58]

- Atif Qarni is a former U.S. Marine who served for eight years, including in Iraq; he is a Democrat politician who was appointed as the 19th Virginia Secretary of Education.[59]

Entertainment

Shayan Khan, is an American Entrepreneur, Model, Actor, Entertainer and Producer. Khan was awarded the title of Mr. Pakistan World in 2013, and has finished the filming of his first feature film Na Band Na Baarati, in Toronto, Canada on October 17, 2016.

Sports

- Gibran Hamdan is an American football quarterback, who is the first player of Pakistani descent to play in the NFL.

- Mustafa Ali is the first wrestler of Pakistani descent to compete for the WWE.

Socioeconomics

Occupation and income

The Pakistani American community generally lives in a comfortable middle-class, upper-middle-class[11][33] and upper-class lifestyles.[60] Many Pakistani Americans follow the residence pattern set by other immigrants to the United States that when they increase their wealth, they are able to own or franchise small businesses; including restaurants, groceries and convenience stores, clothing and appliance stores, petrol and gas stations, newspaper booths, and travel agencies. It is common to include members of the extended and immediate family in the business.

Members of the Pakistani community believe in the symbolic importance of owning homes; accordingly, Pakistani Americans tend to save money and make other monetary sacrifices earlier on in order to purchase their own homes as soon as possible.[11] Members of the family and sometimes the closer community tend to take care of each other, and to assist in times of economic need. Hence, it would be more common to turn to a community member for economic assistance rather than to a government agency. This leads to relatively low use of welfare and public assistance by Pakistani-Americans.[11] According to the 2000 census, the mean household income in the United States in 2002 was $57,852 annually, whereas for Asian households, which includes Pakistanis this was $70,047.[4] A separate study conducted by the American Community Survey in 2005, showed the mean and median incomes for Pakistani male full-time workers were US$59,310 and US$42,718 - respectively compared to the average male American full-time workers' mean and median incomes of US$56,724 and US$41,965 - respectively.[61] A 2011 report based on data from the 2010 US Census reported the median household income of Pakistani-American families at $63,000, which was considerably higher than the American family income average of $51,369.[62]

There is also incidence of poverty in the Pakistani community and in particular around the growing number of new immigrants that migrated from less privileged backgrounds in Pakistan. These migrants tend to take low-paying jobs involving manual or unskilled labor and tend to live in large cities where such jobs are readily available and in particular New York, where as of the 2000 census, poverty rates for Pakistanis in relation to the total New York population were higher overall, with 28% of Pakistanis living in poverty, which is greater than the general New York City poverty rate of 21%.[63] Compared with those immigrants that arrived from 1965 who were either professionals or students and considered to be middle- and upper-class, the newer migrants tended to be worse off economically.[64]

Education

According to American Factfinder, Pakistani Americans are high achievers academically and tend to be better educated as compared to other heritage groups in the United States with 89.1% being at least high school graduates [65] and about 54% holding a bachelor's degree or higher professional degree.[65] Additionally it was found that over 30% of Pakistani Americans hold graduate or professional degrees.[65]

Physicians

An increasing number of Pakistani Americans work in the medical field. The Association of Physicians of Pakistani Descent of North America, APPNA, has been meeting in various locations across the United States for the past 30 years. There are more than 17,000 doctors practicing medicine in America who are of Pakistani descent.[66] Pakistan is the fourth highest source of IMG doctors in the U.S.[67] and they are chiefly concentrated in New York, California, Florida, New Jersey and Illinois.[68] Pakistan is also the fourth highest source of foreign dentists licensed in the United States.[69] US congressmen and congresswomen have lauded the contributions of Pakistani medical professionals to the country's healthcare system.[70]

Labour

This table shows the areas of work that Pakistanis are employed in and compares people that are born in the U.S., those born in Pakistan and those who are American nationals:[71]

| Occupational characteristics | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Managerial - business/financial-related occupations | % Professional related occupations | % Self-employed | ||

| FB1 | Men | 15.1 | 29.6 | 17.1 |

| FB1 | Women | 8.8 | 32.0 | 9.6 |

| NB2 | Men | 10.0 | 33.3 | 9.9 |

| NB2 | Women | 15.6 | 50.7 | 7.2 |

| NB3 | Men | 17.7 | 18.0 | 14.0 |

| NB3 | Women | 11.9 | 26.7 | 8.2 |

Note: FB1 = Pakistani born, NB2 = American born Pakistani and NB3 = All American nationals

The New York Times estimated that there were 109,300 workers born in Pakistan in all occupations in the US in 2007. With the top 10 occupations in ascending order being; sales-related, managers and administrators, drivers and transportation workers, doctors, accountants and other financial specialists, computer software developers, scientists and quantitative analysts, engineers and architects, clerical and administrative staff, and teachers.[72]

Discrimination

Since the September 11 attacks, there have been scattered incidents of Pakistani Americans having been targets for hate crimes and Pakistani Americans have to go under more security checks in places such as airports. Following these attacks, many Pakistani Americans have identified themselves as Indians to avoid discrimination and obtain jobs (Pakistan was created as a result of the partition of India in 1947).[73]

Politics

Since the second wave of immigration in 1965, the Pakistani American community has not been politically inclined, but this is now changing, with the community starting to contribute funds to their candidates of choice in both parties, and running for elected office in districts with large Pakistani American populations. In recent times, Pakistani American candidates have run for the state senate in districts of such city boroughs as Brooklyn, New York. Because the community is geographically dispersed, the formation of influential voting blocs has not generally been possible, making it difficult to for the community to make an impact on politics in this particular way. However, there are increasing efforts on the part of community leaders to ensure voter registration and involvement. In 1989, observing the need for greater political coordination, activism and advocacy, a group of Pakistani Americans founded The Pakistani American Political Action Committee (PAKPAC).[74]

Historically, Pakistani Americans have tended to vote Republican due to the shared ideology of conservatism and the perceived notion that Republican Presidents and leaders are more pro-Pakistani than Democrats. This was evident during the 2000 Presidential Election, as Pakistani Americans voted in overwhelming numbers for Republican candidate George W. Bush. That trend reversed itself in 2004, after George W. Bush's first term in office. His policies alienated Muslims at home and abroad, and Pakistanis were no exception. When George W. Bush was up for re-election, Pakistani Americans voted for Democratic candidate John Kerry. Former Pakistan diplomat Mohammed Sadiq (diplomat) helped establish the internship program at the Pakistan Embassy in Washington, D.C. Mr. Sadiq also helped the Pakistani American community organize and launch the Pakistan Caucus in Capitol Hill.

In the past, especially during the Cold War and the War on Terror under the Bush administration, there was the perceived notion that Republicans were more pro-Pakistani than Democrats. However, that trend reversed itself from 2011 onwards. Since then, there has been an increasing anti-Pakistani sentiment among Republican congressman which has alienated some Pakistani-Americans. Some Republican presidential candidates have criticised the Democrats policy toward Pakistan. During the 2012 Republican Party presidential debates, the Republican candidates questioned whether the United States could trust Pakistan. Texas governor Rick Perry called Pakistan unworthy of US aid because it had not done enough to help fight al-Qaeda.[75] In the same year a bill was introduced by Dana Rohrabacher in the US House of Representatives proposing a hefty reduction in aid to Pakistan.[76] President Obama has vowed to veto any proposed anti-Pakistan bills.[77] President Obama also courted the Pakistani-American community for votes and money for his 2012 re-election campaign. In March 2012, Obama traveled to Houston, Texas for this purpose and at a dinner organised by Pakistani entrepreneurs, the President managed to raise $3.4 million in just a few hours for his re-election campaign. President Obama also pledged to continue sending aid and selling military equipment to Pakistan. According to polls, most Pakistani-Americans have now switched their votes to the Democratic Party.[78]

In 2013, during the second inauguration of Barack Obama, the re-elected President praised the members of the Pakistani community in America and said, “I am about to go speak to the crowd in Chicago, but I wanted to thank you first. I want you to know that this was not fate and it was not an accident. You made this happen.” Talking to the Daily Times via telephone, US business leader Muhammad Saeed Sheikh said Obama in his address told that he would spend the rest of his presidency honoring the Pakistani-American support and doing what he can to finish what he started. Obama continued his praise and said, "You organised yourselves block by block. You took ownership of this campaign 5 and 10 dollars at a time. And when it was not easy, you pressed forward."[79]

In January 2019, Sadaf Jaffer became the first female Pakistani-American mayor, the first female Muslim American mayor, and the first female South Asian mayor in the United States, of Montgomery in Somerset County, New Jersey.[80]

Relations with Pakistan

Pakistani Americans have always maintained a strong bond with their homeland. No airlines are allowed to fly nonstop to the US from Pakistan, but several Arab airlines fly indirectly between the two nations, carrying with them thousands of Pakistanis who mostly go home to visit family and relatives. The relationship between the U.S. and Pakistani governments in the past few decades has not been very close, and the Pakistani American community has benefited from this American interest in the country of their origin. Pakistani TV channels have found their way into homes of the diaspora worldwide.[74]

Several paid TV channels are available for viewing; Pakistani TV serials, reality TV shows and political talk shows are popular among expatriates. These channels can also be viewed on the internet. Pakistani Americans maintain a deep interest in the society and politics of their country of origin. Funds are raised by the community in the US for various political parties and groups in Pakistan. From all the Pakistani diaspora, Pakistani Americans raised the largest number of funds to help Pakistan due to the 2005 earthquake. Tensions among ethnic groups like the Sindhis, Punjabis, Pashtuns, and Baluchis in Pakistan are not reflected in interaction between these subgroups in the US. Several international airlines serve the growing Pakistani community in the US connecting major US airports to those in Pakistan.

The Pakistani community in the United States also remits the largest share of any Pakistani diaspora community since 2002/03, surpassing those from Saudi Arabia which from 2000/01 were $309.9 million and increased to $1.25 billion by 2007/08 and during the same period remittances from the United States increased from $73.3 million to $1.72 billion.[61]

In 2012 the Election Commission of Pakistan granted Overseas Pakistanis the right to vote in future Pakistani general elections. By allowing the setting up of polling stations in embassies and consulates, this move was welcomed by those Pakistanis living abroad particularly in America who stated "Overseas Pakistanis make enormous contributions to the development of Pakistan".[81][82]

In American popular culture

- Nadia Ali is a Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter, prominent in electronic dance music and the voice of the single "Rapture", which dominated dance charts across the world.

- In the Emmy-Nominated TV series Silicon Valley, Dinesh Chugtai is the lead software engineer in the fictional tech company "Pied Piper." He is originally from Islamabad and is often seen speaking Urdu and making remarks about his homeland. Dinesh has a sarcastic personality and is known for his frequent quarrels with co-worker "Bertram Gilfoyle". The character is played by Pakistani-American actor Kumail Nanjiani.

- In the popular sitcom Seinfeld, Babu Bhatt is a Pakistani immigrant befriended by Jerry Seinfeld in the episode "The Cafe." He appears again in "The Visa," in which he moves into Jerry's building, but Babu is deported to Pakistan due to Jerry not giving him his immigration paperwork (which was mistakenly delivered to his mailbox).

- Mr. Capone-E is a rapper from San Gabriel Valley in Los Angeles, California.

- Nadia Yassir, a character on the hit TV show 24, portrayed a fictional Pakistani American.[83]

- In fall 2007, CW aired a comedy show titled Aliens in America. The show is about a Wisconsin family that hosts a Pakistani exchange student.[84]

- Faran Tahir is a Pakistani American actor who has appeared in hit American television shows such as 24, Monk, and Justice. He also starred as the captain in the 2009 Star Trek movie.

- The latest character in Marvel Comics to take up the mantle of Ms. Marvel is Kamala Khan, a Pakistani American in the Millennial Generation (Generation Y). Her character and comic (of which she is the title character) have received critical acclaim, along with being a commercial success.[85]

- The Kominas are a Boston-based Pakistani American band, prominent in the punk and taqwacore scenes, appearing in the documentary Taqwacore: the Birth of Punk Islam in 2009.

- American rapper Future's 2016 single Low Life's lyrics referenced a 'b**** from Pakistan' twice.[86]

- Homeland, a popular US television drama, based its fourth season in Islamabad, Pakistan.[87]

- The Brink was an American television comedy focused on a geopolitical crisis in Pakistan.

- Last Resort was an American military drama television series was based on Pakistan.

- Madam Secretary's first season's episode three was based on a diplomatic crises with Pakistan.

- Popular U.S series The Simpsons included a remark from Krusty the Clown regarding 'India nuked Pakistan'. The series also showed Springfield's port featuring a restaurant is named "The Karachi Hibachi."

- 2016 HBO mini-series The Night Of was based around a Pakistani American family based in Queens, New York.

Events

- Pakistan day flag raising events are held throughout the US around August 14 every year.[88]

- Pakistan Independence Day Parade: The event is held every year around August 14 (the date Pakistan was established in 1947) in New York City

- The First International Urdu Conference was held in the United Nations Headquarters in New York in June 2000. The conference was organized by Urdu Markaz New York.

- APPNA Conference: This event is organized every year by APPNA (Association of Pakistani Physicians in North America). The conference attracts hundreds of Pakistani American physicians and their families from all over North America. APPNA's doctors have also volunteered their time and services for a free health care event taking place throughout June 2010.[89]

- Pakistan Independence Day Festival of Battery Park: This is the largest gathering of Pakistani Americans in United States which was founded by a political and social activist, Khalid Ali.

- In April 2010, the USA Cricket Association signed a deal with the Pakistan Cricket Board (PCB) to host games in America. The PCB said that they had reached an agreement with the USA Cricket Association and anticipated games starting in 2010.[90] This is also due to the large Pakistani American and Pakistani expatriate community residing in the United States.

Notable people

See also

Notes and references

- "PEOPLE REPORTING ANCESTRY 2018: ACS 5-Year Estimates Detailed Tables". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on May 8, 2020. Retrieved May 8, 2020.

- "Who Are Pakistani Americans?" (PDF). Cdn.americanprogress.org. Retrieved August 17, 2018.

- Pakistanis in America March 2, 2012

- Pakistanis in U.S. Archived December 27, 2016, at the Wayback Machine, May 20, 2010.

- United States Census Bureau. "US demographic census". Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved November 19, 2006.

- "City of Paterson - Silk City". Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved November 9, 2013.

- "The Asian Population: 2010" (PDF). The Asian Population: 2010. U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved May 23, 2020.

- "Press Releases 2010". Embassy of the United States Islamabad, Pakistan. June 16, 2010. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- Aminah Mohammad-Arif (2007). "The Paradox of Religion: The (re)Construction of Hindu and Muslim Identities amongst South Asian Diasporas in the United States". South Asia Multidisciplinary Academic Journal. Samaj.revues.org (1). doi:10.4000/samaj.55. Archived from the original on March 6, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- Pakistan Link - Nayyer Ali Archived October 22, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- Pavri, Tinaz. "PAKISTANI AMERICANS". Archived from the original on May 6, 2006. Retrieved April 10, 2006.

- Pakistanis in New England Archived May 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved May 19, 2010.

- "Yearbook of Immigration Statistics: 2011 Supplemental Table 2". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Archived from the original on August 8, 2012. Retrieved July 11, 2012.

- Census Profile: NYC's Pakistani American Population Archived April 25, 2005, at the Wayback Machine

- "Pakistanis in New York City (graphic)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on October 23, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- 2018, UBM (UK) Ltd. "Pakistan International ends New York service in late-Oct 2017". Routesonline. Retrieved June 8, 2018.CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link)

- Ed Murray (August 16, 2015). "Pakistan Day Parade a display of pride in their heritage and America". New Jersey On-Line LLC. Archived from the original on August 19, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- Michelle Sahn (August 15, 2015). "ICYMI: Pakistan Day Parade To Be Held Sunday In Woodbridge, Edison". Woodbridge Patch. Archived from the original on August 17, 2015. Retrieved August 16, 2015.

- Aatif Awan (2 December 2019), "Opinion: Why Pakistani startups are the next big thing", MENAbytes. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

- We are California, Featured group Pakistanis, Pg 1 Archived May 13, 2009, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved September 8, 2011

- Ajay K. Mehrotra (2005). "Pakistanis". Encyclopedia of Chicago. Archived from the original on November 9, 2013. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- Pakistani community in North Texas Archived December 11, 2011, at the Wayback Machine Retrieved September 25, 2011

- "Consulate General of Pakistan Houston". Pakistanconsulatehouston.org. Archived from the original on March 9, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "Pakistani American Leadership Center". PAL-C. Archived from the original on April 3, 2015. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- Community Overview - Pakistan Consulate General Archived November 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved November 29, 2010.

- "Pakistani ancestry maps". Epodunk.com. Archived from the original on May 7, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- Cities with Pakistani Ancestry Archived July 31, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved May 22, 2010.

- "Boonton, NJ". Epodunk.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "Lincolnia, VA". Epodunk.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "Stafford, TX". Epodunk.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "Avenel, NJ". Epodunk.com. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "Migration Information Source - Spotlight on the Foreign Born of Pakistani Origin in the United States". Migrationinformation.org. Archived from the original on May 30, 2010. Retrieved May 11, 2010.

- Pakistanis in California Pg 2 Archived July 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved May 21, 2010.

- Brian Solomon (September 5, 2012). "Shahid Khan: The New Face Of The NFL And The American Dream". Forbes. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- Shahid Khan on Forbes

- Adil Najam (2006). Portrait of a Giving Community: Philanthropy by the Pakistani-American Diaspora. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674023666. Archived from the original on May 25, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "Published in Midland Reporter-Telegram". Legacy. 2015-03-24. Retrieved 8/6/2019. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - Staff; Midl; Reporter-Telegram (January 18, 2019). "PBPA honors S. Javaid Anwar with Top Hand Award". Midland Reporter-Telegram. Retrieved August 6, 2019.

- Javaid Anwar - Honour Highlights, retrieved August 6, 2019

- Kovach, Gretel C. (November 22, 2009). "Fort Hood soldier says Army, Islam share common values". Dallas News. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- Batalova, Jeanne (May 15, 2008). "Immigrants in the U.S. Armed Forces". Migration Policy Institute. Archived from the original on December 4, 2014. Retrieved November 16, 2014.

- Tempest, Ron (May 25, 2002). "U.S. Heroes Whose Skills Spoke Volumes". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on November 22, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- Lowrey, Colonel Nathan S. (2011). U.S. Marines in Afghanistan, 2001-2002: From the Sea (PDF). Washington, D.C.: History Division, United States Marine Corps. pp. 299–300. ISBN 978-0-16-089557-9. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 29, 2014.

Khan, Asad A. (October 28, 2009). "AFPAK Underlying Issues - Not Addressed". Congressman Jim McDermott. United States House of Representatives. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014. - Tate, David (October 22, 2010). "When afghan First Means Afghan Last". POV. PBS. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- "Yearly Chronologies of the United States Marine Corps - 2004". History Division. United States Marine Corps. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

Hope Hodge (May 13, 2013). "Recent reliefs indicate new fine line for Marine Corps commanders". Marine Corps Times. Archived from the original on December 18, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014. - "Humayun Saqib Muazzam Khan: Captain, United States Army". Arlington Cemetery. June 9, 2004. Archived from the original on November 28, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- Considine, Craig (May 26, 2013). "Honoring Muslim American Veterans on Memorial Day". Huffington Post. Archived from the original on November 15, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- Ballhaus, Rebecca (July 28, 2016). "Khizr Khan, Father of Muslim Army Officer Killed in Iraq, Challenges Donald Trump". Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on May 25, 2017.

- "Pakistani Americans in US military". Pakistani American Public Affairs Committee. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 20, 2014.

- The Illustrated History of American Military Commissaries: The Defense Commissary Agency and its predecessors, since 1989. Government Printing Office. p. 475. ISBN 9780160872464.

- Berman, Nina (March 22, 2005). "Purple Hearts: Back from Iraq". Open Democracy. Archived from the original on November 26, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- Hall, Kenneth (September 2, 2006). "Pakistani-American soldier guest at State of Union". Soundoff. Archived from the original on November 28, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- "Guests of First Lady Laura Bush". ABC News. January 31, 2006. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- "Pakistani-American soldier laid to rest". Dawn. March 20, 2005. Archived from the original on November 29, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- Christensen, Nathan (May 14, 2007). "Pakistan-Born U.S. Naval Aviator Reaches Career Milestone". America's Navy. Archived from the original on November 25, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- Roesch, Kelli (May 13, 2009). "Pakistani-American Soldier Compelled to Serve in U.S. Army". DVIDS. Archived from the original on November 27, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- "Pakistani American Soldier Dies in the Line of Duty". Pakistan Link. 2004. Archived from the original on November 26, 2014. Retrieved November 15, 2014.

- Getlen, Larry (June 14, 2015). "This ordinary Joe brought down a Russian spy at Hooters". New York Post. Retrieved June 3, 2017.

- Khan, Hasan (August 5, 2016). "Footprints: Marine turned teacher countering Trump's rhetoric". Dawn.com. Retrieved December 24, 2017.

- "Pakistani American millionaires". Washington-report.org. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- "Pakistani Migration to the United States: An economic perspective" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 18, 2011. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- Kugelman, Michael (May 24, 2012). "How affluent are the Pakistani-Americans?". Dawn. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

According to a 2011 report by the Asian American Center for Advancing Justice (AACAJ), which draws on data from the 2010 US Census and other US government sources, the median household income of Pakistani-American families is nearly $63,000. This is considerably higher than the figure for families in America on the whole ($51,369).

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 25, 2011. Retrieved April 21, 2007.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Rajan, Gita (February 9, 2006). New Cosmopolitanisms. ISBN 9780804767842. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- "U.S. Census website". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 26, 2019.

- Shafqat, Saad; Zaidi, Anita K.M. (2007). "Pakistani Physicians and the Repatriation Equation". New England Journal of Medicine. 356 (5): 442–443. doi:10.1056/NEJMp068261. PMID 17267903.

- "IMGs by Country of Origin". Ama-assn.org. Archived from the original on December 23, 2010. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- Archived copy at the Library of Congress (October 4, 2012).

- Foreign-trained dentists licensed in the United States Retrieved July 8, 2011

- Imtiaz, Huma. "US should apologise to Pakistan, NATO pay reparations to soldiers: Congressman Kucinich". Tribune.com.pk. Archived from the original on August 5, 2014. Retrieved June 6, 2014.

- Min, Pyong Gap (2006). Asian Americans. ISBN 9781412905565. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- "Immigration and Jobs: Where U.S. Workers Come From". The New York Times. April 7, 2009. Archived from the original on August 12, 2010. Retrieved May 20, 2010.

- "Pakistanis pose as Indians after NY bomb scare". Reuters. May 7, 2010. Retrieved March 23, 2020.

- Tinaz Pavri, "Pakistani Americans." Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs (3rd ed., vol. 3, Gale, 2014), pp. 425-436. online

- "Republican contenders target Pakistan and Iran". The Irish Times. November 24, 2011. Archived from the original on November 29, 2011.

- "The Pioneer". Archived from the original on December 22, 2015. Retrieved December 14, 2015.

- "Obama might veto bill calling for economic restrictions on Pakistan: White House". The Express Tribune. Archived from the original on February 4, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- "Obama seeks Pakistani Americans support for reelection - WORLD - geo.tv". March 17, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- "Re-elected Obama praises Pak community". Daily Times. Archived from the original on April 16, 2013. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- Olivia Rizzo (May 21, 2019). "First female Muslim mayor in the U.S. calls this N.J. town home". New Jersey On-Line LLC. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

She is now the first female South Asian mayor of a New Jersey municipality and the first female Muslim mayor in the state. She is also believed to be the first female Muslim mayor, female Pakistani-American mayor and first female South Asian-American mayor first in the nation, according to Religionnews.com.

- Overseas Pakistanis get right to vote Archived February 17, 2012, at the Wayback Machine March 1, 2012

- Pakistani-Americans hail voting rights move March 1, 2012

- "Television News, Reviews and TV Show Recaps - HuffPost TV". The Huffington Post. Archived from the original on July 24, 2008. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- "Aliens In America - EW.com". Entertainment Weekly's EW.com. Archived from the original on October 22, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- "Review: Ms. Marvel #1 - Comic Book Resources". Archived from the original on March 6, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- "Future (Ft. The Weeknd) – Low Life". Genius. Archived from the original on March 7, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- Ghias, Shehzad (October 8, 2014). "Pakistan in Homeland: Finally, an accurate portrayal!". www.dawn.com. Archived from the original on March 6, 2016. Retrieved March 6, 2016.

- "Flag Raising 2011 - Pak-American Community Association". Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- "South Asia Mail". Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- "Sports". Archived from the original on October 13, 2012. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

Further reading

- Malik, Iftikhar Haider. Pakistanis in Michigan: A Study of Third Culture and Acculturation (AMS Press, 1989).

- Mosbah, Aissa, Ahmed Mukt Abdhamid Abusef, and Salah Belghoul. "Migration and Immigrant Entrepreneurship among Pakistanis: An Assessment of the State of Affairs." Journal of Management and science, 15.2 (2017): 45–53. online

- Najam, Adil. Portrait of a Giving Community: Philanthropy by the Pakistani American Diaspora (Harvard University: Global Equity Initiative, 2007).

- Pavri, Tinaz. "Pakistani Americans." Gale Encyclopedia of Multicultural America, edited by Thomas Riggs (3rd ed., vol. 3, Gale, 2014), pp. 425–436. online

- Taus-Bolstad, Stacy. Pakistanis in America (Lerner Publications, 2006).

- Williams, Raymond Brady. Religions of Immigrants from India and Pakistan: New Threads in the American Tapestry (Cambridge University Press, 1988). online review