Operation Crusader

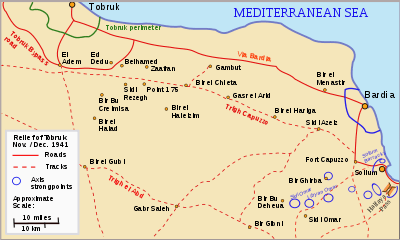

Operation Crusader (18 November – 30 December 1941) was a military operation of the Western Desert Campaign during the Second World War by the British Eighth Army (comprising British, Commonwealth, Indian and Allied contingents), against the Axis forces (German and Italian) in North Africa commanded by Generalleutnant Erwin Rommel. The operation was intended to by-pass Axis defences on the Egyptian–Libyan frontier, defeat the Axis armoured forces and relieve the 1941 Siege of Tobruk.

On 18 November 1941, the Eighth Army launched a surprise attack. From 18 to 22 November, the dispersal of British armoured units led to them suffering 530 tank losses, inflicting Axis losses of about 100 tanks. On 23 November the 5th South African Brigade was destroyed at Sidi Rezegh, while inflicting many German tank casualties. On 24 November Rommel ordered the "dash to the wire", causing chaos in the British rear echelons but allowing the British armoured forces to recover. On 27 November the New Zealanders reached the Tobruk garrison, relieving the siege.

The battle continued into December, when supply shortages forced Rommel to narrow his front and shorten his lines of communication. On 7 December 1941 Rommel withdrew the Axis forces to the Gazala position and on 15 December ordered a withdrawal to El Agheila. The 2nd South African Division captured Bardia on 2 January 1942, Sollum on 12 January and the fortified Halfaya position on 17 January, taking about 13,800 prisoners.[2]

On 21 January 1942 Rommel launched a surprise counter-attack and drove the Eighth Army back to Gazala, where both sides regrouped. This was followed by the Battle of Gazala at the end of May 1942.

Background

Eighth Army

Following the costly failure of Operation Battleaxe, General Archibald Wavell was relieved as Commander-in-Chief Middle East Command and replaced by General Claude Auchinleck. The Western Desert Force was reorganised and renamed the Eighth Army under the command of Lieutenant-General Alan Cunningham replaced by Lieutenant-General Neil Ritchie. The Eighth Army comprised two Corps: XXX Corps under Lieutenant-General Willoughby Norrie and XIII Corps under Lieutenant-General Reade Godwin-Austen.

XXX Corps was made up of 7th Armoured Division (commanded by Major-General William Gott), the understrength South African 1st Infantry Division with two brigades of the Sudan Defence Force (newly arrived from the East African Campaign and commanded by Major-General George Brink) and the independent 22nd Guards Brigade. XIII Corps comprised 4th Indian Infantry Division (commanded by Major-General Frank Messervy), the newly arrived 2nd New Zealand Division (commanded by Major-General Bernard Freyberg) and the 1st Army Tank Brigade.

The Eighth Army also included the Tobruk garrison with the 32nd Army Tank Brigade, and the Australian 9th Division which (in late 1941), was in the process of being replaced by the British 70th Infantry Division and the Polish Carpathian Brigade (commanded by Major-General Stanisław Kopański).Australian Major General Leslie Morshead had been succeeded as Allied commander at Tobruk by British Major General Ronald Scobie. However, by November, the Australian 20th Brigade remained in Tobruk, under Brigadier John Murray.

In reserve, the Eighth Army had the South African 2nd Infantry Division, making a total equivalent of about seven divisions with 770 tanks (including many of the new Crusader Cruiser tanks, after which the operation was named, and new American M3 Stuart light tanks). Air support was provided by up to 724 combat aeroplanes of the Commonwealth air forces in the Middle East and Malta, with direct support under the command of Air HQ Western Desert.[lower-alpha 8]

Panzergruppe Afrika

Panzergruppe Afrika (General Erwin Rommel) comprised the Deutsches Afrika Korps (Lieutenant-General Ludwig Cruwell) comprising the 15th Panzer Division, 21st Panzer Division (total of 260 tanks ), the Division z.b.V Afrika, a composite formation, renamed the 90th Light Africa Division in late November and the Italian 55th Infantry Division Savona.[lower-alpha 9]

The Italian High Command (General Ettore Bastico) disposed the XX Motorised Corps (Lieutenant-General Gastone Gambara) and XXI Corps. The XX Motorised Corps had the 132nd Armoured Division Ariete with 146 M13/40 medium tanks and the 101st Motorised Division Trieste. XXI Corps (Lieutenant-General Enea Navarini) had the 17th Infantry Division Pavia, 102nd Motorised Division Trento, 27th Infantry Division Brescia and 25th Infantry Division Bologna.[lower-alpha 10]

The Axis forces had built a defensive line of strong points along the escarpment running from near the sea at Bardia and Sollum and further along the border wire to Fort Capuzzo. Elements of the 21st Panzer and the Savona divisions manned these defences whilst Rommel kept the rest of his forces grouped near or around the Tobruk perimeter, where an attack on 14 November had been put back to 24 November due to supply difficulties.[6] Axis air support consisted of about 120 German and 200 Italian serviceable aeroplanes but these could be reinforced quickly by transfer of units from Greece and Italy.

Prelude

Axis supply

A German motorised division needed 360 tonnes (350 long tons) per day, and moving the supplies 480 kilometres (300 mi) took 1,170 2.0-tonne (2-long-ton) lorries. With seven Axis divisions, and air and naval units, 71,000 tonnes (70,000 long tons) of supplies per month were needed. The Vichy French agreed to the use of Bizerta but no supplies reached the port until late 1942. From February to May 1941, a surplus of 46,000 tonnes (45,000 long tons) was delivered; attacks from Malta had some effect, but in May, the worst month for ship losses, 91 percent of supplies arrived. Lack of transport in Libya left German supplies in Tripoli, and the Italians had only 7,000 lorries to transport supplies to 225,000 men. A record amount of supplies arrived in June but at the front shortages worsened.[7]

There were fewer Axis attacks on Malta from June and the British increased the proportion of ships sunk from 19% in July, to 25% in September, when Benghazi was bombed and ships diverted to Tripoli; air supply in October made little difference. Deliveries averaged 73,155 t (72,000 long tons) per month from July to October but the consumption of 30 to 50 per cent of fuel deliveries by road transport and a truck unserviceability rate of 35 per cent reduced deliveries to the front. In November, during Operation Crusader, a five-ship convoy was sunk and air attacks on road convoys stopped journeys in daylight. (Lack of deliveries and the Eighth Army offensive forced a retreat to El Agheila from 4 December, crowding the Via Balbia where British ambushes destroyed about half of the remaining Axis transport.)[8]

Convoys to Tripoli resumed and ship losses increased but by 16 December, the supply situation had eased except for the fuel shortage; in December the Luftwaffe was restricted to one sortie per day. The Vichy French sold 3,700 tonnes (3,600 long tons) of fuel, U-boats were ordered into the Mediterranean and air reinforcements sent from Russia in December. The Italian navy used warships to carry fuel to Derna and Benghazi, then made a maximum effort from 16 to 17 December. Four battleships, three light cruisers and 20 destroyers escorted four ships to Libya. The use of an armada for 20,000 tonnes (20,000 long tons) of cargo ships depleted the navy fuel reserve and only one more battleship convoy was possible. Bizerta in Tunisia was canvassed as an entrepôt but this was in range of RAF aircraft from Malta and was another 800 kilometres (500 mi) west of Tripoli.[9]

Eighth Army plan

The plan was to engage the Afrika Korps with the 7th Armoured Division while the South African Division covered their left flank. Meanwhile, on their right, XIII Corps, supported by 4th Armoured Brigade (detached from 7th Armoured Division), would make a clockwise flanking advance west of Sidi Omar and hold position threatening the rear of the line of Axis defensive strongpoints, which ran east from Sidi Omar to the coast at Halfaya. Central to the plan was the destruction of the Axis armour by 7th Armoured Division to allow the relatively lightly armoured XIII Corps to advance north to Bardia on the coast whilst XXX Corps continued north-west to Tobruk and link with a break-out by the 70th Division. There was also a deception plan to persuade the Axis that the main Allied attack would not be ready until early December and would be a sweeping outflanking move through Jarabub, an oasis on the edge of the Great Sand Sea, more than 150 mi (241 km) to the south of the real point of attack. This proved successful to the extent that Rommel, refusing to believe that an attack was imminent, was not in Africa when it came.[10]

Battle

First phase

18 November

Before dawn on 18 November, the Eighth Army launched a surprise attack, advancing west from its base at Mersa Matruh and crossing the Libyan border near Fort Maddalena, some 50 miles (80 km) south of Sidi Omar, and then pushing to the north-west. The Eighth Army was relying on the Desert Air Force to provide them with two clear days without serious air opposition but torrential rain and storms the night before the offensive resulted in the cancellation of all the air-raids planned to interdict the Axis airfields and destroy their aircraft on the ground.[11] At first all went well for the Allies. The 7th Armoured Brigade of the 7th Armoured Division advanced north-west towards Tobruk with 22nd Armoured Brigade to their left. XIII Corps and the New Zealand Division made its flanking advance with 4th Armoured Brigade on its left and 7th Infantry Brigade of the 4th Indian Division on its right flank at Sidi Omar. On the first day no resistance was encountered as the Eighth Army closed on the enemy positions.

On the morning of 19 November, in an action at Bir el Gubi, the advance of the 22nd Armoured Brigade was blunted by the Ariete Division which knocked out many British tanks at the start of the battle.[12] In the centre of the division, 7th Armoured Brigade and the 7th Support Group raced forward almost to within sight of Tobruk and took Sidi Rezegh airfield, while on the right flank 4th Armoured Brigade came into contact that evening with a force of 60 tanks supported by 88 mm gun batteries and anti-tank units from 21st Panzer Division (which had been moving south from Gambut) and became heavily engaged.[13][14]

On 20 November, 22nd Armoured Brigade fought a second engagement with the Ariete Division and 7th Armoured repulsed an infantry counter-attack by the 90th Light and Bologna Divisions at Sidi Rezegh. 4th Armoured fought a second engagement with 21st Panzer pitting the speed of their Stuart tanks against the heavier German guns.

The Eighth Army was fortunate at this time that 15th Panzer Division had been ordered to Sidi Azeiz, where there was no British armour to engage. However, 4th Armoured soon started to receive intelligence that the two German Panzer divisions were linking up. In his original battle plan Cunningham had hoped for this so that he would be able to bring his own larger tank force to bear and defeat the Afrika Korps armour. By attaching 4th Armoured Brigade to XIII Corps, allowing 22nd Armoured Brigade to be sidetracked fighting the Ariete Division and letting 7th Armoured Brigade forge towards Tobruk, his armoured force was by this time hopelessly dispersed. 22nd Armoured Brigade were therefore disengaged from the Ariete and ordered to move east and support 4th Armoured Brigade (while infantry and artillery elements of 1st South African Division were to hold the Ariete) and 4th Armoured were released from their role of defending XIII Corps' flank.[15]

In the afternoon of 20 November, 4th Armoured were engaged with 15th Panzer Division (21st Panzer having temporarily withdrawn for lack of fuel and ammunition). It was too late in the day for a decisive action but 4th Armoured nevertheless lost some 40 tanks and by this time were down to less than two-thirds their original strength of 164 tanks. 22nd Armoured arrived at dusk, too late to have an impact, and during the night of 20 November, Rommel pulled all his tanks north-west for an attack on Sidi Rezegh.[15]

Tobruk

The Eighth Army plans for 21 November were for 70th Division to break out from Tobruk and cut off the Germans to the southeast. The 7th Armoured would advance from Sidi Rezegh to link with them and roll up the Axis positions around Tobruk. The New Zealand Division (XIII Corps) would exploit the decline of the 21st and 15th Panzer and advance 30 mi (48 km) north-east to the Sidi Azeiz area, overlooking Bardia. The 70th Division attack surprised the Axis, Rommel having underestimated the size and armoured strength of the garrison. On the evening of 20 November, Scobie ordered a break-out on 21 November by the 70th Division (2nd/King's Own, 2nd BlackWatch, 2nd/Queen's and 4th RTR with Matilda tanks).[16] The Polish Carpathian Brigade was to mount a diversion just before dawn to pin the Pavia Division. During the operation, one-hundred guns were to bombard the Bologna, Brescia and Pavia positions on the Tobruk perimeter with 40,000 rounds.[17]

Fighting was intense as the three pronged attack, consisting of the 2nd King's Own on the right flank, the 2nd Battalion, Black Watch as the central force and the 2nd Queen's Own on the left flank, advanced to capture a series of prepared strongpoints leading to Ed Duda.[18] Initially, the Italians were stunned by the massive fire and a company of the Pavia was overrun in the predawn darkness, but resistance in the Bologna gradually stiffened.[19][lower-alpha 11]

By mid afternoon elements of 70th Division had advanced some 3.5 miles (5.6 km) towards Ed Duda on the main supply road when they paused as it became clear that 7th Armoured would not link up.[21] The central attack by the Black Watch involved a murderous charge under heavy machine gun fire, attacking and taking various strongpoints, until they reached strongpoint Tiger. The Black Watch lost an estimated 200 men and their commanding officer.[22][lower-alpha 12] The British renewed their advance but the attack petered out when the infantry involved were unable to capture the Bologna defences around the Tugun strongpoint.[lower-alpha 13]

That day, 21 November, another fierce action was fought with high casualties by elements of the German 155th Rifle Regiment, Artillery Group Bottcher, 5th Panzer Regiment and the British 4th, 7th and 22nd Armoured Brigades for possession of Sidi Rezegh and the surrounding height in the hands of Italian infantry and anti-tank gunners of the Bologna. On 22 November General Scobie ordered the position to be consolidated and the corridor widened in the hope that the Eighth Army would link up. The 2nd York and Lancaster Regiment, with tank support, took strongpoint Tiger leaving a 7,000 yd (6,400 m) gap between the corridor and Ed Duda, but efforts to clear the ‘Tugun’ and ‘Dalby Square’ strong points were repelled. In the fighting on the 22nd, the ‘Tugun’ defenders brought down devastating fire, reducing the strength in one attacking British company to just thirty-three all ranks. [19]

Second phase

Sidi Rezegh

On 23 November, the 70th Division in Tobruk attacked the 25th Bologna in an attempt to reach the area of Sidi Rezegh, but elements of the Pavia soon arrived and broke up the British attack.[lower-alpha 14] On 26 November, Scobie ordered a successful attack on the Ed Duda ridge, and in the early morning hours of 27 November the Tobruk garrison linked up with a small force of New Zealanders.[22]

7th Armoured had planned its attack northward to Tobruk to start at 08.30 on 21 November. However, at 07.45 patrols reported the arrival from the south-east of a mass of enemy armour, some 200 tanks in all. 7th Armoured Brigade, together with a battery of field artillery turned to meet this threat leaving the four companies of infantry and the artillery of the Support Group to carry through the attack to the north in anticipation of being reinforced by 5th South African Infantry Brigade which had been detached from the 1st South African Division at Bir el Gubi facing the Ariete Division and was heading north to join them.[25]

Without armoured support the northward attack by the Support Group failed and by the end of the day, 7th Armoured Brigade had lost all but 28 of its 160 tanks and were relying by that time mainly on the artillery of the Support Group to hold the enemy at arm's length. The South African brigade was dug in southeast of Bir el Haiad but had the German armour between them and Sidi Rezegh. However, by the evening of 21 November, 4th Armoured was 8 miles (13 km) south east of Sidi Rezegh and 22nd Armoured Brigade were in contact with the German armour at Bir el Haiad, some 12 miles (19 km) south-west of Sidi Rezegh.[26]

Overnight Rommel once again split his forces with 21st Panzer taking up a defensive position alongside the Afrika Division between Sidi Rezegh and Tobruk and 15th Panzer moving 15 miles (24 km) west to Gasr el Arid to prepare for a battle of manoeuvre which General Ludwig Crüwell believed would favour the Afrika Korps. This presented a clear opportunity for a breakthrough to Tobruk with the whole of 7th Armoured Division concentrated and facing only the weakened 21st Panzer. However, XXX Corps commander Norrie, aware that 7th Armoured division was down to 200 tanks decided on caution.[27]

Instead, in the early afternoon Rommel attacked Sidi Rezegh with 21st Panzer and captured the airfield. Fighting was desperate and gallant: for his actions during these two days of fighting Brigadier Jock Campbell, commanding 7th Support Group, was awarded the Victoria Cross. However, 21st Panzer, despite being considerably weaker in armour, proved superior in its combined arms tactics, pushing 7th Armoured Division back with a further 50 tanks lost (mainly from 22nd Brigade).[27] The fighting at Sidi Rezegh continued through 22 November, with South African Division's 5th Brigade by that time engaged to the south of the airfield. An attempt to recapture it failed and the Axis counter-offensive began to gain momentum. 7th Armoured Brigade withdrew with all but four of their 150 tanks out of commission or destroyed.[28] In four days the Eighth Army had lost 530 tanks against Axis losses of about 100.[29]

The most memorable action during the North African campaign of the 3rd Field Regiment, (Transvaal Horse Artillery) was during the battle of Sidi Rezegh on 23 November 1941. The South Africans were surrounded on all sides by German armour and artillery, subjected to a continuous barrage. They tried to take cover in shallow slit trenches. In many places the South African soldiers could only dig down to around 9 in (23 cm) deep due to the solid limestone underneath their positions.[30] The Transvaal Horse Artillery engaged German tanks from the 15th and 21st Panzer divisions, the gunners firing over open sights as they were overrun. This continued until many of the officers were dead and the gunners had run out of ammunition.

Many of the gun crews were captured. As darkness fell, those that could escaped back to Allied lines under cover of darkness.[31] The gunners of the 3rd Field Regiment managed to save five of their 24 guns from the battlefield. They later recovered a further seven guns.[32] After the battle of Sidi Rezegh, Acting Lieutenant General Sir Charles Willoughby Moke Norrie stated that the South African's "sacrifice resulted in the turning point of the battle, giving the Allies the upper hand in North Africa at that time."[33][34]

Frontier

On the XIII Corps front on 22 November, the 5th New Zealand Brigade advanced north-east to capture Fort Capuzzo on the main Sollum–Bardia road.[35] The Brigade attacked Bir Ghirba, south of Fort Capuzzo and the headquarters of the Savona Division but was repulsed. To the south, the 7th Indian Brigade captured Sidi Omar and most of the Libyan Omar strong points, the two westernmost strong points of the Axis border defences. Losses in its supporting tank units caused a delay in attacks on the other strong points until replacements arrived.[36] One of the New Zealand military unit's historians described the fighting days as the 7th Indian Brigade's most difficult, with the men of the 4/16th Punjab Battalion having "fought all morning to overcome resistance" and the German 12th Oasis Company having "formed the backbone of the defence of the whole position".[37][lower-alpha 15]

On 23 November, the 5th New Zealand Brigade continued its advance south-east, down the main road from Fort Capuzzo towards Sollum and cut off of the Axis positions from Sidi Omar to Sollum and Halfaya from Bardia and its supply route. The 6th New Zealand Brigade Group on the left flank at Bir el Hariga, had been ordered north-west along the Trigh Capuzzo (Capuzzo–El Adem) to reinforce 7th Armoured Division at Sidi Rezegh.[39] The brigade arrived at Bir el Chleta, some 15 miles (24 km) east of Sidi Rezagh, at first light on 23 November, where they stumbled on the Afrika Korps headquarters and captured most of its staff (Crüwell was absent); no supplies reached either panzer division that day.[40] Later in the day the 4th New Zealand Brigade Group was sent north of the 6th New Zealand Brigade to apply pressure on Tobruk and the 5th New Zealand Brigade covered Bardia and the Sollum–Halfaya positions.

Totensonntag

On 23 November, known to the Germans as Totensonntag (Sunday of the Dead) Rommel gathered his two panzer divisions in an attack with the Ariete Armoured Division to cut off and destroy the rest of XXX Corps. In the pocket were the remains of 7th Armoured Division, 5th South African Infantry Brigade and elements of the recently arrived 6th NZ Brigade.[41] By the end of the day the 5th SA Brigade had been destroyed and what remained of the defending force broke out of the pocket, heading south towards Bir el Gubi.[41] Comando Supremo in Rome agreed to put the XX Mobile Corps, including the Ariete Armoured Division and the Trieste Motorised Division, under Rommel's command.[42] By 23 November, Ariete, Trieste and Savona had knocked out about 200 British tanks and a similar number of vehicles were disabled or destroyed. British losses from 19 to 23 November were around 350 tanks destroyed and 150 severely damaged.[43] Axis losses were considerable, with the Afrika Korps down to forty operational tanks.

Dash to the wire

On 24 November Rommel ordered the Afrika Korps and Ariete division to push east, hoping to relieve the siege of Bardia and the frontier garrisons,[44] and pose a large enough threat to the British rear echelon to complete the defeat of Operation Crusader. They headed for Sidi Omar, causing chaos and scattering the mainly rear echelon support units in their path, splitting XXX Corps and almost cutting off XIII Corps.[lower-alpha 16] On 25 November, the 15th Panzer Division set off north-east for Sidi Azeiz, found the area empty and were constantly attacked by the Desert Air Force. South of the border, the 5th Panzer Regiment of the 21st Panzer Division attacked the 7th Indian Brigade at Sidi Omar and were repulsed by the 1st Field Regt RA, firing over open sights at a range of 500 m (547 yd); a second attack left the 5th Panzer Regiment with few operational tanks.[46] The rest of 21st Panzer Division had headed north-east, south of the border, to Halfaya.[47]

By the evening of 25 November, the 15th Panzer Division was west of Sidi Azeiz (where the 5th NZ Brigade headquarters was based) and down to 53 tanks, practically the entire remaining tank strength of the Afrika Korps.[47] The Axis column had only a tenuous link to its supply dumps on the coast between Bardia and Tobruk and supply convoys had to find a way past the 4th and 6th NZ Brigade Groups. On 26 November, the 15th Panzer Division, bypassed Sidi Azeiz and headed for Bardia for supplies, arriving around midday. The remains of the 21st Panzer Division attacked north-west of Halfaya towards Capuzzo and Bardia and Ariete, approaching Bir Ghirba (15 mi (24 km) north-east of Sidi Omar) from the west, was ordered towards Fort Capuzzo to clear any opposition and link with the 21st Panzer Division.[48] They were to be supported by the depleted 115th Infantry Regiment of the 15th Panzer Division, which was to advance with some artillery south-east from Bardia towards Fort Capuzzo.[49]

The two battalions of the 5th NZ Brigade, between Fort Capuzzo and Sollum Barracks, were engaged by the converging elements of the 15th and 21st Panzer divisions at dusk on 26 November. During the night, the 115th Infantry Regiment got to within 800 yd (732 m) of Capuzzo but was disengaged to switch its attack towards Upper Sollum to meet 21st Panzer coming from the south. In the early hours of 27 November, Rommel met with the commanders of the 15th and 21st Panzer divisions at Bardia. The Afrika Korps had to return to the Tobruk front, where the 70th Infantry Division and the New Zealand Division had gained the initiative. On 25 November, in the 102nd Trento Infantry Division sector, the 2nd Battalion Queens Royal Regiment attacked the Bondi strongpoint but was repulsed. The garrison of Tugun, down to half their strength, exhausted and low on ammunition, food and water, surrendered on the evening of 25 November, after having defeated a British attack the previous night.[50]

While Gruppe Böttcher contained the British tank attacks in the Bologna sector, a battalion of Bersaglieri from Trieste counter-attacked the British break-out from Tobruk.{{efn|Afterwards Oberstleutnant Bayerlein wrote,

On 25 November heavy fighting flared up again at Tobruk, where our holding force was caught between pincers, one coming from the south-east and the other from the fortress itself. By mustering all their strength, the Boettcher Group succeeded in beating off most of these attacks, and the only enemy penetration was brought to a standstill by an Italian counterattack.[51]

Rommel ordered the 21st Panzer Division back to Tobruk and the 15th Panzer Division was to attack forces thought to be besieging the border positions between Fort Capuzzo and Sidi Omar. The 15th Panzer Division would first have to capture Sidi Azeiz to provide space for this ambitious manoeuvre. Neumann-Silkow felt the plan had little chance of success and resolved to advance to Sidi Azeiz (where he believed there was a British supply dump), before heading to Tobruk.[52] Defending the 5th Brigade HQ at Sidi Azeiz was a company of the 22nd New Zealand Infantry Battalion and the armoured cars of the New Zealand divisional cavalry plus some field artillery, anti-tank, anti-aircraft and machine gun units. The New Zealanders were overrun early on 27 November and Rommel was present to congratulate Brigadier James Hargest on the determined New Zealand defence; 700 prisoners were taken although the armoured cars escaped.[53]

The 21st Panzer Division ran into the 5th NZ Brigade 22nd battalion at Bir el Menastir, while heading west to Tobruk from Bardia and after an exchange lasting most of the day was forced to detour south via Sidi Azeiz, delaying their return to Tobruk by a day.[54] By early afternoon it became clear to the Eighth Army HQ through radio intercepts that both divisions of the Afrika Korps were heading west to Tobruk, with the Ariete Division on their left.[55] The audacious manoeuvre by Afrika Korps had failed, while coming within 4 mi (6 km) of the main supply base of the Eighth Army.[56] The dash of the Afrika Korps to the south removed a severe threat to the left flank of the New Zealand Division which had remained ignorant of the danger because news of the losses of the 7th Armoured Division had not reached XIII Corps and German tank losses had been wildly overestimated. The New Zealand Division engaged elements of the Afrika,Trieste, Bologna and Pavia divisions, advancing westwards to re-take Sidi Rezegh airfield and the overlooking positions to the north leading to Tobruk.[57] The 70th Infantry Division resumed its attack on 26 November and next day elements linked with the advancing New Zealanders of the 4th NZ Brigade at Ed Duda on the Tobruk by-pass; the 6th NZ Brigade cleared the Sidi Rezegh escarpment in a mutually-costly engagement.[58]

Third phase

27 November

At midday on 27 November, the 15th Panzer Division reached Bir el Chleta and met the 22nd Armoured Brigade, which had been re-organised as a composite regiment with less than fifty tanks. By the afternoon, the 22nd Armoured Brigade was holding on and the 4th Armoured Brigade, with seventy tanks, had arrived on the left flank of the 15th Panzer Division, having dashed over 20 mi (32 km) north-east and was harassing its rear echelons. The 15th Panzer Division was also suffering many losses from bombing.[55] As night fell, the British tanks disengaged to replenish but inexplicably moved south to do this, leaving the route west open for the 15th Panzer Division. Once again the New Zealand Division, engaged in heavy fighting on the south-east end of the tenuous corridor into Tobruk, would be under threat from the Afrika Korps.[59]

By 27 November, the situation of the Eighth Army had improved; XXX Corps had reorganised after the chaos of the breakthrough and the New Zealand Division had linked up with the Tobruk garrison. Auchinleck had spent three days during the period of the breakthrough with Cunningham who had wanted to halt the offensive and withdraw but Auchinleck handed Cunningham written orders on 25 November which included the sentence "...There is only one order, Attack and Pursue"[60] On returning to Cairo on 26 November, after conferring with his superiors, Auchinleck relieved Cunningham and appointed his deputy Chief of Staff, Major-General Neil Ritchie, promoting him to acting lieutenant-general.

Tobruk corridor

From 26 to 27 November, in a determined attack, the 70th Infantry Division killed or captured the Italian defenders of several concrete pillboxes before reaching Ed Duda. On 27 November, the 6th New Zealand Brigade fought a fierce battle with a battalion of the 9th Bersaglieri Regiment, who having dug themselves in among the Prophet's Tomb, used their machine guns to great effect. The New Zealand brigade managed to link up with the 32nd Tank Brigade at Ed Duda and the 6th and 32nd brigades secured a small bridgehead on the Tobruk front but this was to last for five days. By 28 November, the Bologna had regrouped largely in the Bu Amud and Belhamed areas and the division was now stretched out along 8 mi (13 km) from the Via Balbia to the Bypass Road, fighting in several places. The Reuters correspondent with the Tobruk garrison wrote on 28 November that:

The division holding the perimeter continues to fight with utmost bravery and determination. They are stubbornly holding small isolated defence pits, surrounded with barbed wire.

— Reuters[61]

On the night of 27/28 November, Rommel had discussed with Crüwell plans for the next day, indicating that his priority was to cut the Tobruk corridor and destroy the enemy forces fighting there. Crüwell wanted to eliminate the threat of the 7th Armoured Division tanks to the south and felt this needed attention first. 15th Panzer spent most of 28 November once more engaged with 4th and 22nd Armoured and dealing with supply problems. Despite being outnumbered by two to one in tanks and at times immobile because of lack of fuel, 15th Panzer succeeded in pushing the British tank force southwards, while moving westwards.[62]

Fierce fighting continued through 28 November around the Tobruk corridor with the battle ebbing and flowing. It had not been possible to create a firm communications link between the 70th and the New Zealand divisions, making co-ordination between the two somewhat difficult. When two Italian motorised battalions of Bersaglieri together with supporting tanks, anti-tank guns and artillery moved towards Sidi Rezegh, they overran a New Zealand field hospital. The Bersaglieri captured 1,000 patients and 700 medical staff.[63] They also freed some 200 Germans being held captive in the enclosure on the grounds of the hospital.[64] The New Zealand Official History mentions the capture of 1,000 patients and implies that they were captured by Germans:

The cooks were preparing the evening meal in the grouped MDSs on 28 November when over the eastern ridge of the wadi appeared German tracked troop-carrying vehicles, from which sprang men in slate-grey uniforms and kneeboots, armed with tommy guns, rifles, and machine guns. ‘They're Jerries!’ echoed many as the German infantrymen ran down into the wadi and, as if to show that they did not intend to be trifled with, fired a few bullets into the sand.[65]

At 1800 hours the Australian 2/13th Battalion moved to reinforce Ed Duda, where some platoons suffered severe casualties from intense shelling.[66]

On the night of 28 November Rommel rejected Crüwell's plan for a direct advance towards Tobruk (having had no success with head-on attacks on Tobruk during all the months of the siege). He decided on a circling movement to attack Ed Duda from the south-west and carry on through to cut off the enemy forces outside the Tobruk perimeter and destroy them.[67]

On the morning of 29 November, 15th Panzer set off west travelling south of Sidi Rezegh. The remnants of 21st Panzer were supposed to be moving up on their right to form a pincer but were in disarray when von Ravenstein failed to return from a reconnaissance that morning, having been captured. In the afternoon, to the east of Sidi Rezegh, the 21st Battalion of New Zealanders was overrun on the much contested Point 175 by elements of the Ariete Division.[68] The New Zealanders were caught wrong-footed, having mistaken the attackers for reinforcements from the 1st South African Brigade which had been due to arrive from the southwest to reinforce XIII Corps.[69]

According to Lieutenant-Colonel Howard Kippenberger who later rose to command the New Zealand 2nd Division

About 5.30 p.m. damned Italian Motorized Division (Ariete) turned up. They passed with five tanks leading, twenty following, and a huge column of transport and guns, and rolled straight over our infantry on Pt. 175.[70]

The 24th and 26th Battalions met a similar fate at Sidi Rezegh on 30 November and on 1 December a German armoured attack on Belhamed practically destroyed the 20th Battalion.[71] The New Zealanders suffered heavily in the attacks: 879 dead, 1,699 wounded, 2,042 captured.[72]

Meanwhile, the leading elements of 15th Panzer reached Ed Duda but made little progress before nightfall, against determined defences. However, a counter-attack by 4th Royal Tank Regiment supported by Australian infantry recaptured the lost positions and the German units fell back 1,000 yards (914 m) to form a new position. During 29 November the two British Armoured Brigades were strangely passive. The 1st SA Brigade was to all intents and purposes tied to the armoured brigades, unable to move in open ground without them because of the threat from the panzer divisions. On the evening of 29 November, 1st SA Brigade was placed under command of 2nd New Zealand Division and ordered to advance north to recapture Point 175. Meanwhile, radio intercepts had given the Eighth Army to believe that 21st Panzer and Ariete were in trouble and Lieutenant-General Ritchie ordered the 7th Armoured Division to "stick to them like hell".[73]

Eight Matilda tanks provided the preliminary bombardment for a counter-attack by two companies of the 2/13th Australian Infantry Battalion on the night of 29/30 November. In a bayonet charge against German positions, the 2/13th lost two killed and five wounded and took 167 prisoners.[66][74] Following the resistance at Ed Duda Rommel decided to withdraw 15th Panzer to Bir Bu Creimisa, 5 miles (8 km) to the south, and relaunch his attack northeast from there on 30 November aiming between Sidi Rezegh and Belhamed while leaving Ed Duda outside his encircling pocket. By mid afternoon the New Zealand 6th Brigade was being heavily pressed on the western end of the Sidi Rezegh position. The weakened 24th Battalion was overrun as were two companies of 26th Battalion although on the eastern flank of the position 25th Battalion repelled an attack from the Ariete moving from Point 175.[75]

At 06:15 on 1 December 15 Panzer renewed their attack towards Belhamed, supported by a massive artillery effort and once again the New Zealand Division came under intense pressure. During the morning, 7th Armoured Division was ordered to advance to provide direct assistance. 4th Armoured Brigade arrived at Belhamed and may have had the opportunity for a decisive intervention since they outnumbered the 40 or so 15th Panzer Division tanks attacking the position but they believed their orders were to cover the withdrawal of the remains of 6th NZ Brigade, which precluded an offensive operation.[76]

The remains of 2nd NZ Division were now concentrated near Zaafran, five miles east of Belhamed and slightly further north-east of Sidi Rezegh. During the morning of 1 December, Freyberg, commanding 2nd New Zealand Division, saw a signal from the Eighth Army indicating that the South African Brigade were now to be under command of 7th Armoured Division. He drew the inference that Army HQ had given up hope of holding the Tobruk corridor and signalled mid-morning that without the South Africans his position would be untenable and that he was planning a withdrawal. Orders were issued by Freyberg to be ready to move east at 17.30. 15th Panzer, which had been resupplying, renewed its attack at 16.30 and the Trieste cut the tenuous link established with Tobruk.[77] The New Zealanders became involved in a desperate fighting withdrawal from its western positions and showing admirable discipline, was formed up by 17:30 and having paused an hour for the tanks and artillery to join them from the west, set off at 18:45. They reached the XXX Corps lines with little further interruption and in the early hours the 3,500 men and 700 vehicles which had emerged were heading back to Egypt.[78]

Sollum

Once again Rommel became concerned with the cut off units in the border strongpoints and on 2 December, believing that he had won the battle at Tobruk,[79] sent the Geissler Advance Guard and the Knabe Advanced Guard battalion groups to open the routes to Bardia and to Capuzzo and thence Sollum. On 3 December the Geissler Advance Guard were heavily defeated by elements of 5th NZ Brigade on the Bardia road near Menastir. To the south the Knabe force at the same time fared slightly better on the main track to Capuzzo (Trigh Capuzzo), coming up against 'Goldforce' (based on the Central India Horse reconnaissance regiment) and retiring after an artillery exchange.[80]

Rommel insisted once again on trying to relieve the frontier forts. All Afrika Korps tanks were undergoing overhaul, so he ordered the rest of 15th Panzer and the Italian Mobile Corps eastwards on 4 December which caused considerable alarm at the Eighth Army HQ. However, Rommel soon realised he could not deal with the situation at Tobruk and also send a strong force east and the Ariete went no further than Gasr el Arid.

Ed Duda

On 4 December Rommel launched a renewed attack on Ed Duda which was repulsed by 70th Division's 14th Infantry Brigade. When it was clear that the attack would fail Rommel resolved to withdraw from the eastern perimeter of Tobruk to allow him to concentrate his strength against the growing threat from XXX Corps to the south.

Bir el Gubi

Following the withdrawal of 2nd NZ Division, Ritchie had reorganised his rear echelon units to release the 5th and 11th Indian Infantry Brigades of the 4th Indian Infantry Division and the 22nd Guards Brigade. By 3 December the 11th Indian Infantry Brigade was in action against a strongpoint near Bir el Gubi, about 25 mi (40 km) south of Ed Duda. The I and II battalions, 136th "Giovani Fascisti" Regiment from this hilltop position fought off repeated attacks by the British armour and Indian infantry units during the first week of December;

Although Norrie had an overwhelming superiority in every arm in the area of Bir Gubi, the failure to concentrate them and co-ordinate the action of all arms in detail had allowed one Italian battalion group to frustrate the action of his whole corps and inflict heavy casualties on one brigade.

— John Gooch[81]

The Eighth Army infantry were left vulnerable because Norrie had been ordered to send the 4th Armoured Brigade east to cover against the developing threat to Bardia and Sollum.[82] On 4 December, the "Pavia" and "Trento" Divisions counter-attacked the 70th Infantry Division to contain them within the Tobruk perimeter and reportedly recaptured the Plonk and Doc strong points.[83] On 5 December, the 11th Indian Infantry Brigade continued its attrition attack against Point 174. As dusk approached the Afrika Korps and the "Ariete" armoured division intervened to relieve the Young Fascist garrison at Point 174 and attack 11th Indian Infantry Brigade. Crüwell was unaware that 4th Armoured Brigade, with 126 tanks, was over 20 miles (32 km) away and he withdrew to the west. The Indian Brigade had to be withdrawn to refit and be replaced by the 22nd Guards Brigade.[84] Crüwell could have attacked on 6 December as the 4th Armoured Brigade made no move to close up to 22nd Guards Brigade but hesitated for too long and was unable to strike a conclusive blow before dark. By 7 December, the 4th Armoured Brigade had closed up and the opportunity lost; Neumann-Silkow, the commander of the 15th Panzer Division was mortally wounded late on 6 December.[85]

Gazala line

On 7 December the 4 Armoured Brigade engaged 15th Panzer, disabling 11 more tanks. Rommel had been told on 5 December by the Italian Comando Supremo that supply could not improve until the end of the month when the airborne supply from Sicily would start. Realising that success was now unlikely at Bir el Gubi, he decided to narrow his front and shorten his lines of communication by abandoning the Tobruk front and withdrawing to the positions at Gazala, 10 miles (16 km) to his rear, which had been in preparation by Italian rear echelon units and which he had occupied by 8 December.[86] He placed the Italian X Corps at the coastal end of the line and Italian XXI Corps inland. The weakened Italian Mobile Corps anchored the southern end of the line at Alem Hamza while the Afrika Korps were placed behind the southern flank ready to counterattack.[87]

On 6 December, Rommel ordered his divisions to retreat westwards, leaving the Savona to hold out as long as possible in the Sollum, Halfaya and Bardia area. They continued to fight for another month and a half. That night, the 70th Division captured the German-held Walter and Freddie strong points without any resistance; a Pavia battalion made a stand on Point 157, inflicting heavy casualties on the 2nd Durham Light Infantry with its dug-in infantry before being overcome after midnight.[88] Despite the German 90th Light Division pulling out of the Tobruk sector on 4 December, the Bologna Division held out until the night of 8–9 December when trucks were finally assigned to give them some support.[89] In a final action on the part of the British 70th Division, the Polish Carpathian Brigade attacked elements of the Brescia Division, covering the Axis retreat and captured the White Knoll position.[90] The Tobruk defenders were finally relieved as a result after a nineteen-day battle.

In the hope of getting better co-ordination between his infantry and armour, Ritchie transferred 7th Armoured Division to XIII Corps and directed XXX Corps HQ to take South African 2nd Division under command and conduct a siege of the border fortresses. He also sent forward to XIII Corps the 4th Indian Infantry Division and 5th NZ Infantry Brigade.[87] The Eighth Army launched its attack on the Gazala line on 13 December. 5th NZ Brigade attacked along an eight-mile front from the coast while 5th Indian Infantry Brigade made a flanking attack at Alem Hamza. Although the Trieste Division successfully held Alem Hamza, 1st battalion The Buffs from 5th Indian Infantry succeeded in taking point 204, some miles west of Alem Hamza. They were thus left in a vulnerable salient and 7th Indian Infantry Brigade to their left were ordered to send northwards 4th battalion 11th Sikh Regiment, supported by guns from 25th Field Regiment and 12 Valentine tanks from 8th Royal Tank Regiment, to ease their position.[91] This force found itself confronted by the Afrika Korps fielding 39 tanks together with 300 lorries of infantry and guns.[91] Once again the 7th Armoured Division were not in place to intervene and it was left to the force's artillery and supporting tanks to face the threat. Taking heavy casualties, they nevertheless managed to knock out fifteen German tanks and stall the counterattack.[92]

Godwin-Austen ordered Gott to get the British armour to a position where it could engage the Afrika Korps, unaware that Gott and his senior commanders were no longer confident they could defeat the enemy directly, despite their superiority in numbers, because of the Germans' superior tactics and anti-tank artillery, favoured making a wide detour to attack the enemy's soft-skinned elements and lines of supply to immobilise them.[93]

On 14 December the Polish Independent Brigade was brought forward to join the New Zealanders and prepare a new attack for the early hours of 15 December. The attack went in at 03:00, taking the defenders by surprise. The two brigades made good progress but narrowly failed to breach the line.[94]

Meanwhile, on 14 December, to the south, there was little activity from the Afrika Korps and 7th Indian Infantry Brigade were limited to patrolling through a shortage of ammunition as supply problems multiplied.[95] At Alem Hamza 5th Indian Brigade renewed their attack but made no progress against determined defence and at Point 204 5th Indian Brigade's battalion of the Royal East Kent Regiment ("The Buffs"), supported by ten I tanks, an armoured car squadron of the Central India Horse, a company of Bombay Sappers and Miners and the artillery of 31st Field Regiment and elements of 73rd Anti-Tank Regiment and some anti-aircraft guns,[96] were attacked by ten or twelve tanks, the remnants of the Ariete Armoured Division, which they beat off.

On 15 December, the Brescia and Pavia, with Trento in close support, repelled a strong Polish–New Zealand attack, thus freeing the German 15th Panzer Division which had returned to the Gazala Line, to be used elsewhere,

The Poles and New Zealanders made good initial progress, but the Italians rallied well, and by noon it was clear to [General Alfred] Godwin-Austen that his two brigades lacked the weight to achieve a breakthrough on the right flank. It was the same story in the centre, where the Italians of ‘Trieste’ continued to repulse 5th Indian Brigade’s attack on Point 208. By mid-afternoon the III Corps attack had been fought to a halt all along the line.

— Richard Humble[97]

Rommel considered Point 204 a key position and so great a part of the available neighbouring armoured and infantry units were committed to attack it on 15 December and in fierce and determined fighting, the attacking force, the Ariete and the 15th Panzer Division, with the 8th Bersaglieri Regiment and the 115th Lorried Infantry Regiment, overran The Buffs and its supporting elements during the afternoon. The Buffs lost over 1,000 men killed or captured with only 71 men and a battery of field artillery escaping.[98] Fortunately for the rest of 5th Indian Brigade it was by then too late in the day for the attacking force to collect itself and advance further to intervene at Alem Hamza.[99] The attackers too had suffered heavily in the engagement: the German commander was heard on a radio intercept to report the inability of his force to exploit his success because of losses sustained.[98] By 15 December Afrika Korps were down to eight working tanks, although the Ariete still had some 30. Rommel, who had greater respect for the capabilities of 7th Armoured at this time than either Crüwell (or apparently even Gott), became very concerned about a perceived flanking move to the south by the British armour. Despite the vehement objections of the Italian generals as well as Crüwell, he ordered an evacuation of the Gazala line on the night of the 15th.[100]

By the afternoon of 15 December, 4th Armoured, having looped round to the south, was at Bir Halegh el Eleba, some 30 miles (48 km) northwest of Alem Hamza and ideally placed both to strike at the rear of the Afrika Korps and advance north to cut Panzer Group Afrika's main lines of communication along the coast, which Godwin-Austen was urging them to do. However, early on 16 December only a small detachment was sent north (which caused serious confusion among Panzer Group Afrika's rear echelon but was not decisive) while the rest of the brigade headed south to meet its petrol supplies. In the afternoon 15th Panzer moving west were able to pass by 4th Armoured's rear and block any return move to the north. While the mere presence of the British armour had tipped Rommel's hand to withdraw from Gazala, the opportunity to gain a decisive victory had been missed.[101]

Aftermath

Over the following ten days Rommel's forces withdrew to a line between Ajedabia and El Haseia, maintaining his lines of communication and avoiding being cut off and surrounded as the Italians had been the previous year. As his lines of supply shortened and supplies to El Agheila improved he was able to rebuild his tank force while correspondingly the Eighth Army lines of supply became more and more stretched. On 27 December Rommel was able in a three-day tank battle at El Haseia to inflict heavy damage on the 22nd Armoured Brigade, forcing the leading echelons of the Eighth Army to withdraw.[102] This allowed the Axis forces to fall back to a tactically more desirable defensive line at El Agheila during the first two weeks of January without having to deal with pressure from the enemy.[102]

Auchinleck's determination and Ritchie's aggression had removed the Axis threat to Egypt and the Suez Canal for the time being. However the Axis strongholds on the Libya–Egypt border remained, despite Rommel's recommendation that they be evacuated by sea, to block the coast road and tie down Allied troops. Early in December the Allies decided that clearing the Axis frontier positions was essential to facilitate their supply lines and maintain the momentum of their advance. On 16 December the 2nd South African Division commenced an attack on Bardia, garrisoned by 2,200 German and 6,600 Italian troops and on 2 January 1942 the port fell. Sollum fell to the South Africans on 12 January after a small fiercely fought engagement, surrounding the fortified Halfaya Pass position (which included the escarpment, the plateau above it and the surrounding ravines) and cut it off from the sea. The Halfaya garrison, of 4,200 Italians of the 55th Savona Infantry Division and 2,100 Germans, was already desperately short of food and water.[103] The defences allowed the garrison to hold out against heavy artillery and aerial bombardment with relatively few casualties but hunger and thirst forced a capitulation on 17 January.[104] Rommel reported of General Fedele de Giorgis, "Superb leadership was shown by the Italian General de Giorgis, who commanded this German-Italian force in its two months' struggle".[105]

On 21 January Rommel launched a surprise counter-attack from El Agheila. Although the action had originally been a "reconnaissance in force", finding the Eighth Army forward elements to be dispersed and tired, in his typical manner he took advantage of the situation and drove the Eighth Army back to Gazala where they took up defensive positions along Rommel's old line. Here a stalemate set in as both sides regrouped, rebuilt and reorganised. While it may have proved a limited success, Operation Crusader showed that the Axis could be beaten and was a fine illustration of the dynamic, back and forth fighting which characterised the North African Campaign. Geoffrey Cox wrote that Sidi Rezegh was the "forgotten battle" of the Desert War. Crusader was "won by a hair’s breadth" by the Eighth Army but "had we lost it, we would have had to fight the battle of Alamein six months or a year earlier, without the decisive weapon of the Sherman tank".[106]

See also

- List of World War II Battles

- North African Campaign timeline

- List of World War II North Africa Airfields

Notes

- XXX Corps had 477 tanks, XIII Corps 135 tanks; Tobruk garrison 126; 339 tanks were cruiser models, 210 the latest A15 Crusader. Infantry tanks: 201, most being Matilda IIs; 173 were M3 Stuarts and 25 were light tanks.[3]

- 650 planes (550 serviceable) in Egypt and 74 (66 serviceable) in Malta.[4]

- 65,000 German soldiers and 54,000 Italian.[2]

- 70 Panzer II, 139 Panzer III, 35 Panzer IV L/24 and 146 Fiat M13/40; 260 German (15 Panzer I, 40 Panzer II, 150 Panzer III, 55 Panzer IV L/24) and 154 Italian tanks.[3][5]

- Potential Axis serviceable reserve of 750 aircraft in Tripolitania, Sicily, Sardinia, Greece and Crete, excluding transport aircraft, aircraft in mainland Italy or part of the Italian Navy.[4]

- 2,900 killed, 7,300 wounded and 7,500 missing. Casualties have been rounded by source due to underlying flaws with primary source data but cover all the serious fighting of November, December and the first half of January.[2]

- 14,600 German casualties: 1,100 killed, 3,400 wounded and 10,100 missing. 23,700 Italian casualties: 1,200 killed, 2,700 wounded and 19,800 missing. Casualties have been rounded by source due to underlying flaws with primary source data but cover all the serious fighting of November, December and the first half of January.[2]

- 650 aircraft (550 serviceable) were based within Egypt and the remaining 74 (66 serviceable) were based in Malta.[4]

- Most Italian infantry divisions in North Africa were classed as Motor-Transportable, with enough motor vehicles to carry all artillery and services but not the infantry, which could be motorised only by vehicles which were attached to corps and army headquarters and always busy moving supplies, the italian infantry divisions fought as purely "leg-mobile" units for all the North Africa campaign.

- While officially a fully motorised unit, the Trento had been forced to give up most of its trucks for supply duties, and fought for all the North Africa campaign as a "leg-mobile" unit, with its 7th Bersaglieri Regiment almost permanently detached as a Corps-level motorised reserve asset.

- "Although the attack was only supposed to be a feint, the Polish Brigade (1 Pulk Artylerii), attacked as if it was the main thrust ... The Poles slaughtered the Italians defending the sector. It was the Poles' first taste of victory on a large scale since the war had begun almost two years earlier."[20]

- In summing up the experience of the 2nd Battalion the Black Watch in the attack, the Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45 wrote that: "The superlative élan of the Black Watch in the attack had been equalled by the remarkable persistence of the defence in the face of formidable tank-and-infantry pressure."[22]

- Acknowledged in the Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–45, The more elaborate attack on Tugun went in at 3 pm and gained perhaps half the position, together with 256 Italians and many light field guns; but the Italians in the western half could not be dislodged and the base of the break-out area remained on this account uncomfortably narrow.[23]

- A German post-war report recorded "After a sudden artillery concentration the garrison of Fortress Tobruk, supported by sixty tanks, made an attack on the direction of Bel Hamid at noon, intending at long last unite with the main offence group. The Italian troops besieging the fortress, tried to offer resistance; in the confusion they were forced to relinquish numerous strong points about Bir Bu Assaten. The Pavia was committed for a counterattack and managed to seal off the enemy breakthrough."[24]

- Another account is given in Information Bulletin Number 11, US War Department. This says: All Italians captured between 22 November and 23 November in the Omars belonged to the Savona Division and were reported to be tougher on the whole and better disciplined than the Italians of the Trento Division captured in December 1940 and June 1941. The prisoners were a well-clothed, well-disciplined group, who had put up a good fight and knew it. The 6 German and 52 Italian officers, as well as the 37 German technicians, were very bitter about their capture and would not speak.[38]

- His decision was based on the fact that the 7th Armoured Division had been defeated but he ignored intelligence reports of British supply dumps lying in his path on the border and this was to cost him the battle. As Oberstleutnant (Lieutenant-Colonel) Fritz Bayerlein, the chief of staff of the Afrika Korps said after the war, "If we had known about those dumps we could have won the battle".[45]

Citations

- Jaroslav Hrbek and Vít Smetana: Draze zaplacená svoboda I, Paseka Praha 2009 p. 117 (czech)

- Playfair 2004, p. 97.

- Playfair 2004, p. 30.

- Playfair 2004, p. 15.

- Rommel, p. 156 (Chapter written by Fritz Bayerlein).

- Clifford 1943, p. 123.

- Creveld 1977, pp. 182–187.

- Creveld 1977, pp. 189–190.

- Creveld 1977, pp. 190–192.

- Hunt 1990, pp. 72–73.

- Clifford 1943, p. 127.

- French, p.219

- Toppe, Vol. II, p.A-8-3

- Clifford 1943, pp. 130–133.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 88–90.

- "World War: Tobruk, After 33 Weeks". Time. 8 December 1941 – via content. time. com.

- Clifford 1943, p. 161.

- Maughan, pp. 439–442

- Greene & Massignani 1999, pp. 116, 121, 126, 122.

- Koskodan, p. ?

- Murphy 1961, pp. 91–93.

- Murphy 1961, p. 93.

- Murphy 1961, p. 94.

- Toppe, Vol. II, Annexe 8 p. A-8-6

- Murphy 1961, p. 96.

- Murphy 1961, p. 98.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 103–105.

- Clifford, pp. 142–144

- Murphy 1961, p. 108.

- Matthews, p.

- Glass, p.?

- Hurst, C.O. history of the Transvaal horse artillery Archived 4 November 2014 at the Wayback Machine Website of the Transvaal Horse Artillery.

- Horn, K. P.46.

- Bentz, p.

- Murphy 1961, p. 119.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 124–127.

- Murphy 1961, p. 214.

- U.S. Military Intelligence Service (15 April 1942). "Information Bulletin No. 11, U.S. War Department". The Battle of the Omars. Lonesentry.com. p. 41. Retrieved 14 April 2008.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 136–137.

- Murphy 1961, p. 151.

- Toppe, Vol. II, pp.A-8-7 to A-8-8

- Murphy 1961, p. 203.

- Mitcham 2008, p. 550.

- Toppe, Vol. II, p.A-8-9

- Millen 1997, p. 216.

- Murphy 1961, p. 299.

- Murphy 1961, p. 304.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 315–332.

- Murphy 1961, p. 325.

- Lyman (2009), pp. 269, 268

- Rommel, pp. 167–168

- Murphy 1961, pp. 330–331.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 336–340.

- Murphy 1961, p. 342.

- Murphy 1961, p. 354.

- Clifford 1943, pp. 149–150.

- Rommel, p. ?

- Murphy 1961, pp. 286–297.

- Murphy 1961, p. 355.

- Clifford 1943, p. 157.

- The Indian Express, 2 December 1941

- Murphy 1961, p. 367.

- "I Bersaglieri in Africa Settentrionale website" (in Italian). 2003. Retrieved 8 April 2008.

- Greene & Massignani 1999, pp. 121–122.

- McKinney (1952), p.168

- Peter Cox, 2015, Desert War: The Battle of Sidi Rezegh, Wollombi, NSW, Exisle Publishing, pp. 156–157.

- Murphy 1961, p. 390.

- Kiwi veterans' website: The Western Desert Accessed 29 December 2007

- Murphy 1961, pp. 400–402.

- Kippenberger (1949), p. 101

- "I: The Desert Campaign of 1941—Prisoners in Italian Hands - NZETC". www.nzetc.org.

- Thomson 2000, p. 187.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 406, 411.

- Maughan, pp. 475–8.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 418–422.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 452.

- Chant 2013, p. 37.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 458–464.

- "Getting it very badly wrong". 8 February 2009.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 476–478.

- Gooch, p. 100

- Murphy 1961, pp. 479–480.

- The New York Times, 5 December 1941; J. L Ready, p. 313

- Murphy 1961, p. 479.

- Murphy 1961, p. 483.

- Murphy 1961, p. 484.

- Murphy 1961, p. 490.

- Maughan, p. 509

- Mitcham 2008, p. 553.

- Koskodan, p. ?

- Mackenzie (1951), p.166

- Murphy 1961, p. 495.

- Murphy 1961, p. 496.

- Murphy 1961, p. 497.

- Mackenzie (1951), p.167

- Mackenzie (1951), p. 168

- Humble 1987, p. 187.

- Mackenzie (1951), p. 169

- Murphy 1961, pp. 499–500.

- Murphy 1961, p. 501.

- Murphy 1961, pp. 502–504.

- Toppe, Vol. II, p. A-8-15.

- Playfair 2004, pp. 95–96.

- Clifford 1943, pp. 219–221.

- Greene & Massignani 1999, p. 130.

- Cox 1987, p. 196.

References

- Bentz, G. (2012). "From El Wak to Sidi Rezegh: The Union Defence Force's First Experience of Battle in East and North Africa, 1940–1941". Scientia Militaria: South African Journal of Military Studies. South Africa: Stellenbosch University. XL (3): 177–199. OCLC 851625548.

- Chant, Christopher (2013). The Encyclopedia of Codenames of World War II. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-64787-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clifford, Alexander (1943). Three Against Rommel: The Campaigns of Wavell, Auchinleck and Alexander. London: George G. Harrap. OCLC 10426023.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Creveld, M. van (1977). Supplying War: Logistics from Wallenstein to Patton. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-29793-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Cox, Geoffrey (1987). A Tale of Two Battles: Crete & Sidi Rezegh. London: William Kimber. ISBN 0-7183-0642-2.

- Ford, Ken (2010). Operation Crusader 1941. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-500-5.

- French, David (2000). Raising Churchill's Army: The British Army and the War against Germany 1939–1945. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-820641-0.

- Glass, C. (2009). "Sidi Rezegh: Reminiscences of the late Gunner Cyril Herbert Glass, 143458, 3rd Field Regiment (Transvaal Horse Artillery)". Military History Journal. The South African Military History Society / Die Suid-Afrikaanse Krygshistoriese Vereniging. XIV (5). ISSN 0026-4016.

- Gooch, John, ed. (1990). Decisive Campaigns of the Second World War. London: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0-7146-3369-5.

- Greene, Jack; Massignani, Alessandro (1999) [1994]. Rommel's North Africa campaign: September 1940 – November 1942. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo. ISBN 978-1-58097-018-1.

- Horn, K. (2012). South African Prisoner-of-War Experience during and after World War II: 1939 – c.1950 (PhD (unpublished, no ISBN)). Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences Stellenbosch University.

- Humble, Richard (1987). Crusader: Eighth Army's Forgotten Victory, November 1941 – January 1942. London: Leo Cooper. ISBN 978-0-85052-284-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hunt, Sir David (1990) [1966]. A Don at War. Abingdon: Frank Cass. ISBN 0-7146-3383-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kippenberger, Howard (1949). Infantry Brigadier. New Zealand Texts Collection (online ed.). Wellington, NZ: Oxford University Press. OCLC 276433219 – via New Zealand Electronic Text Centre.

- Koskodan, Kenneth K. (2011). No Greater Ally: The Untold Story of Poland's Forces in World War II. Oxford: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84908-479-6.

- Lyman, Robert (2009). The Longest Siege: Tobruk, The Battle That Saved North Africa. Pan Australia. ISBN 978-0-23071-024-5.

- Mackenzie, Compton (1951). Eastern Epic. London: Chatto & Windus. OCLC 1412578.

- Mason, Captain Walter Wynn (1954). "4: The Second Libyan Campaign and After (November 1941 – June 1942)". In Kippenberger, Howard (ed.). Prisoners of War. The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945 (online ed.). Historical Publications Branch, Wellington. OCLC 4372202. Retrieved 6 April 2008.

- Matthews, D. (1997). "With the 5th South African Infantry Brigade at Sidi Rezegh". Military History Journal. The South African Military History Society / Die Suid-Afrikaanse Krygshistoriese Vereniging. X (6). ISSN 0026-4016.

- Maughan, Barton (1966). "10 Ed Duda" (PDF). Tobruk and El Alamein. Australia in the War of 1939–1945, Series 1 – Army. III (1st (online) ed.). Canberra: Australian War Memorial. OCLC 186193977. Retrieved 26 December 2015.

- Millen, Julia (1997). Salute to Service: A History of the Royal New Zealand Corps of Transport and Its Predecessors, 1860–1996. Victoria University Press. ISBN 978-0-86473-324-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitcham, Samuel W. (2008). The Rise of the Wehrmacht: The German Armed Forces and World War II, 1941–43. I. Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-99659-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Murphy, W. E. (1961). Fairbrother, Monty C. (ed.). The Relief of Tobruk. The Official History of New Zealand in the Second World War 1939–1945 (online ed.). Wellington, NZ: War History Branch, Department of Internal Affairs. Retrieved 30 July 2015 – via New Zealand Electronic Text Collection.

- Playfair, Major-General I. S. O.; with Flynn RN, Captain F. C.; Molony, Brigadier C. J. C. & Gleave, Group Captain T. P. (2004) [1st. pub. HMSO 1960]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Mediterranean and Middle East: British Fortunes Reach their Lowest Ebb (September 1941 to September 1942). History of the Second World War United Kingdom Military Series. III. Naval & Military Press. ISBN 1-84574-067-X.

- Rommel, Erwin (1953). Liddell-Hart, Basil (ed.). The Rommel Papers. De Capo Press. ISBN 0-30680-157-4.

- Sadkovich, James. J. (1991). "Of Myths and Men: Rommel and the Italians in North Africa". The International History Review. XIII (2): 284–313. doi:10.1080/07075332.1991.9640582. JSTOR 40106368.

- Spayd, P. A. (2003). Bayerlein: from Afrikakorps to Panzer Lehr: The Life of Rommel's chief-of-staff Generalleutnant Fritz Bayerlein. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7643-1866-5.

- Taylor, A. J. P. (1974). Mayer, S. L. (ed.). A History of World War Two. London: Octopus Books. ISBN 0-7064-0399-1.

- Thomson, John (2000). Warrior Nation: New Zealanders at the Front, 1900–2000. Hazard Press. ISBN 978-1-877161-89-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Toppe, Generalmajor Alfred (1990) [~1947]. German Experiences in Desert Warfare During World War II (PDF). II (The Black Vault ed.). Washington: Historical Division, European Command: US Marine Corps. FMFRP 12-96-II. Retrieved 1 December 2007.

Further reading

- Dando, N. (2014). The Impact of Terrain on British Operations and Doctrine in North Africa 1940–1943 (PhD). Plymouth University. OCLC 885436735. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Montanari, Mario (1993) [1985]. Le operazioni in Africa Settentrionale Tobruk, (marzo 1941 –– gennaio 1942) Parte Seconda. II (2nd online ed.). Roma: Edizione Ufficio Storico SME. OCLC 247554269. Retrieved 25 January 2020 – via issuu.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Operation Crusader. |