Military history of Mexico

The military history of Mexico encompasses armed conflicts within what that nation's territory, dating from before the arrival of Europeans in 1519 to the present era. Mexican military history is replete with small-scale revolts, foreign invasions, civil wars, indigenous uprisings, and coups d’etat by disgruntled military leaders. Mexico's colonial-era military was not established until the eighteenth century. After the Spanish conquest of central Mexico in the early sixteenth century, the Spanish crown did not rely on a standing military, but the crown responded to the external threat of a British invasion by establishing a standing military for the first time following the Seven Years' War (1756–63). The regular army units and militias had a short history when in the early 19th century, the unstable situation in Spain with the Napoleonic invasion gave rise to an insurgency for independence, propelled by militarily untrained, darker complected masses fight for the independence of Mexico. The Mexican War of Independence (1810–21) saw royalist and insurgent armies battling to a stalemate in 1820. That stalemate ended with the royalist military officer turned insurgent, Agustín de Iturbide persuading the guerrilla leader of the insurgency, Vicente Guerrero, to join in a unified movement for independence, forming the Army of the Three Guarantees.[1] The royalist military had to decide whether to support newly independent Mexico. With the collapse of the Spanish state and the establishment of first a monarchy under Iturbide and then a republic, the state was a weak institution. The Roman Catholic Church and the military weathered independence better. Military men dominated Mexico's nineteenth-century history, most particularly General Antonio López de Santa Anna, under whom the Mexican military were defeated by Texas insurgents for independence in 1836 and then the U.S. invasion of Mexico (1846–48). With the overthrow of Santa Anna in 1855 and the installation of a government of political liberals, Mexico briefly had civilian heads of state. The Liberal Reforms that were instituted by Benito Juárez sought to curtail the power of the military and the church and wrote a new constitution in 1857 enshrining these principles. Conservatives comprised large land owners, the Church, and most of the regular army revolted against the Liberals, fighting a civil war. The Conservative military lost on the battlefield. But Conservatives sought another solution, supporting the French intervention in Mexico (1862–65). The Mexican army loyal to the liberal republic were unable to stop the French army's invasion, briefly halting it in with a victory at Puebla on 5 May 1862. Mexican Conservatives supported the installation of Maximilian Hapsburg as Emperor of Mexico, propped up by the French and Mexican armies. With the military aid of the U.S. flowing to the republican government in exile of Juárez, the French withdrew its military supporting othe monarchy and Maximilian was caught and executed. The Mexican army that emerged in the wake of the French Intervention was young and battle tested, not part of the military tradition dating to the colonial and early independence eras.

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Mexico |

|

|

Spanish rule |

|

| Timeline |

|

|

Liberal General Porfirio Díaz was part of the new Mexican military, a hero of the Mexican victory over the French on Cinco de Mayo 1862. He revolted against the civilian liberal government in 1876, and remained continuously in the presidency from 1880 to 1911. Over the course of his presidency, Díaz began professionalizing the army that had emerged. By the time he turned 80 years old in 1910, the Mexican military was an aging, largely ineffective fighting force. When revolts broke out in 1910-11 against his regime, a rebel forces scored decisive victories over the Federal Army in the opening chapter of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920). Díaz resigned in May 1911, but Francisco I. Madero, on whose political behalf rebels rose against Díaz, demobilized the rebel forces and kept the Federal Army in place. "This single decision cost [Madero] the presidency and his life."[2] Army General Victoriano Huerta seized the presidency of Madero in 1913, with Madero murdered in the coup d'etat. Civil war broke out in the wake of the coup. Huerta's Federal Army racked up one defeat after another by the revolutionary armies, with Huerta resigning in 1914. The Federal Army ceased to exist.[3] A new generation of fighting men, most of whom with no formal military training but were natural soldiers, fought now fought against each other in a civil war of the winners. The Constitutionalist Army under the civilian leadership of Venustiano Carranza and the military leadership of General Alvaro Obregón were the victors in 1915. The revolutionary military men were to continue to dominate Mexico's postrevolutionary period, but the military men who became presidents of Mexico brought the military under civilian control, systematically reining in the power of the military and professionalizing the force. The Mexican military has been under civilian government control with no President of Mexico being military generals since 1946.[4] The fact of Mexico's civilian control of the military is in contrast the situation in many other countries in Latin America.[5]

Mexico stood among the Allies of World War II and was one of two Latin American nations to send combat troops to serve in the Second World War. Recent developments in the Mexican military include their suppression of the 1994 Zapatista Army of National Liberation in Chiapas, control of narcotrafficking, and border security.

Pre-Hispanic era, before 1519

Before the arrival of Europeans in 1492, there were many large-scale civilizations in Mesoamerica that had engaged in conquest of rival powers. As civilizations arose, traditional raiding to plunder resources evolved into full-scale conquests between 300 BCE and 150 BCE, with occupying forces that could direct tribute from the conquered to the conquerors. Conquest on a grand scale only occurred with the Aztec Empire, which coalesced in the fifteenth century C.E., but smaller-scale conquests affected the rise and fall of civilizations before that.[6] As early as Teotihuacan and Monte Albán, the first Mesoamerican states, there is evidence of local conquests of defensive walls around urban cores and conflicts resulting in large-scale sacrifice of warriors. There were cycles of conquests over many hundreds of years, resulting in the rise and decline of civilizations.[7]

For many years, scholars depicted the Maya as peaceful, but there is ample evidence of Maya warfare in glyphic written texts and pictorials, as well as archeological evidence of "fortifications, mass graves, and militaristic iconography," indicating warfare's importance.[8] In the 6th century, a series of wars between the Tikal and Calakmul erupted on the Yucatán. The Mayan conflict also included vassal states in the Petén Basin such as Copan, Dos Pilas, Naranjo, Sacul, Quiriguá, and briefly Yaxchilan had a role in initiating the first war. There is also evidence of conquests in the region of the Mixtecs, Zapotecs, and Purépecha (or Tarascans), which were not as extensive as the Aztec empire, but followed the same pattern on a smaller scale.[9]

Prior to Spanish colonization, in the 15th century, several wars ensued between the Aztecs and several other native tribes. Alliances between the Aztec state and Texcoco had become central to these pre colonial wars. Several of these conflicts were evolved to an organized warfare, known as the Flower wars. In the Flower wars the primary objective was to injure or capture the enemy, rather than killing as in Western warfare. Prisoners-of-war were ritually sacrificed to Aztec gods. Cannibalism was also a center feature to this type of warfare. Historical accounts such as that of Juan Bautista de Pomar state that small pieces of meat were offered as gifts to important people in exchange for presents and slaves, but it was rarely eaten, since they considered it had no value; instead it was replaced by turkey, or just thrown away.

Perhaps the most famous of the Native Mexican states is the Aztec Empire. In the 13th and 14th centuries, around Lake Texcoco in the Anahuac Valley, the most powerful of these city states were Culhuacan to the south, and Azcapotzalco to the west. Between them, they controlled the whole Lake Texcoco area.

The Aztecs hired themselves out as mercenaries in wars between the Nahuas, breaking the balance of power between city states. Tenochtitlan, Texcoco, and Tlacopan formed a "Triple Alliance" that came to dominate the Valley of Mexico, and then extended its power beyond. Tenochtitlan, the traditional capital of the Aztec Empire, gradually became the dominant power in the alliance.

The Chichimeca, a wide range of nomadic groups that inhabited the north of modern-day Mexico, were never conquered by the Aztecs.

Spanish conquest of Mexico

The two-year Spanish conquest of the Aztec empire (1519-1521) is the most famous episode of Spanish conquest history. It is documented in the sixteenth century by both Spaniards, their indigenous allies, and indigenous opponents shortly after the events.[10] With arrival of Spaniards in the Caribbean in 1492, they developed patterns of conquest and settlement. From the Caribbean, they went on expeditions (entradas) of exploration, trade, conquest, and settlement. The Spanish crown issued a license for a particular leader to head an expedition, a mature man with wealth, social standing, and ambition to better his position. Explorers probed Mexico's east coast, with Francisco Hernández de Córdoba exploring southeast Mexico in 1517, followed by Juan de Grijalva in 1518. The most important Conquistadores was Hernán Cortés, a settler in Cuba who was well-connected locally. He received a license to lead an expedition of exploration only. As was standard practice for an expedition, those joining it brought their own weapons and armor, and if wealthy enough, a horse. If an entrada of conquest was successful, participants would receive shares of the spoils, with each man receiving one share, and if he was a horseman, an additional share. These expeditions were not organized armies of salaried troops funded by the crown, but groups of settlers turned bands of men in combat or soldiers of fortune, who joined with the expectation that their valor and skill in combat would be rewarded. The term "soldier" was not used by participants themselves. The leader was often called "captain,", but this was not a military rank.[11] Cortés did not want to be restricted by the license limiting him solely to exploration of Mexico's coast, and left Cuba before officials realized his ambition. For that reason, once the Spanish would-be conquerors landed on the mainland, they needed to find way to constitute themselves as a legal entity. They did so by founding the town of Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz (today's Veracruz), and constituting themselves as the city council. They chose Hernán Cortés as their captain.

The conquest of Mexico unfolded along established principles worked out by the Spanish in their twenty years of settlement and expeditions around the Caribbean. Seizing the leader of an indigenous group during a friendly parley was typical, quickly giving Spaniards the advantage. Some groups capitulated immediately and of those some became active allies of the Spanish.[12] The small group of Spaniards realized immediately that the mainland had indigenous populations that were far denser and hierarchically organized societies. The Aztec Empire, the dominant power in central Mexico at the time of European Contact, had conquered indigenous city-states, many of which were chafing under Aztec rule and sought independent status themselves. Cortés quickly realized that he needed indigenous allies for successful conquest and found various indigenous city-states willing to take their chances with these newcomers. From the Spaniards' point of view, the standard strategy of divide-and-conquer was a workable—and winning—strategy. From the indigenous allies' point of view, they formed this alliance with the expectation of bettering their own circumstances. The most important of these allies was the city-state (Nahuatl: altepetl) of Tlaxcala, which the Aztecs had been unable to conquer. The Spanish benefited from another type of ally, an indigenous woman, Malinche or more politely called Doña Marina, who became Cortés's cultural translator. Sent into slavery as a child by her family, she was given as a gift to the Spaniards by a Maya indigenous ally. Malinche was a native speaker of language of the Aztecs, Nahuatl and had learned a Maya language in captivity. She quickly became essential in the Spaniards' ability to negotiate with potential allies and advise the Spaniards about indigenous military strategy and tactics. In sixteenth-century indigenous pictorial accounts of the conquest, such as Codex Azcatitlan, Malinche is shown as an out-sized figure in a leadership position. With their indigenous allies, the Spanish defeated the Aztec empire in a two-year long struggle. They were aided by the outbreak of a smallpox epidemic unintentionally introduced to the mainland by a black slave; the disease disproportionately affected the indigenous populations, since they had no immunity to it.

The Spaniards surrounded and laid siege to the inhabitants of the Aztec's island capital Tenochtitlan, bringing about the Aztecs' total defeat in 1521. Despite their metal weapons, horses, dogs, cannons, and thousands of indigenous allies, the Spanish were unable to subdue the Mexica for seven full months. It was one of the longest continuous sieges in world history.

Several factors contributed to Spanish victory against the Aztecs. Their alliances with indigenous city-states discontented with Aztec rule were crucial to their victory, vastly swelling the number of warriors that could be mobilized in combat. The Aztec empire was fragile politically and militarily, once it became clear that they were beatable. Spanish military technology was superior in many ways, with horses giving Spaniards the advantage in open-field warfare. Iron and steel weapons and harquebuses provided advantages. The Spanish were further aided in their conquest by the Old World diseases (primarily smallpox) they brought with them, to which the natives had no immunity, and which became pandemic, killing large portions of the native population.

Colonial-era control without a standing military

Not until the Spanish empire was by foreign conquest in the eighteenth century did the Spanish crown establish a standing military. Conquests of the central Mexican indigenous civilizations was basically final in the sixteenth century, with the conquest of the Maya region more protracted. Spaniards who had participated in the conquest of central Mexico were rewarded with grants of labor and tribute from city-states which was facilitated by indigenous nobles. The institution of encomienda required the awardees to keep "their Indians" peaceful and to promote their conversion to Christianity. The status of indigenous nobles was recognized by the Spanish crown and were granted the right to carry Spanish arms and ride on horseback, prohibited to commoners. In general, once conquered, the indigenous were incorporated into the Spanish colonial empire as vassals of the crown. There were few rebellions. An exception was the 1541 Mixtón war, where an uprising in what is now Jalisco was suppressed by armed Spaniards and their loyal Tlaxcalan allies led by the highest Spanish administrator, the viceroy, Don Antonio de Mendoza.[13]

The indigenous groups in northern Mexico, collectively called Chichimeca by the Aztecs became fierce and effective warriors against the Spanish once they acquired horses. With the expansion of Spanish exploration northward, these northern indigenous groups were not quickly or permanently subdued and block northern settlement until the discovery of large deposits of silver in Zacatecas. The high value of the silver mines and the need to secure the mining zone and the overland routes to transport silver south and supplies north meant the crown had to create a viable solution. A fifty-year long conflict, the Chichimeca War initially used the construction of presidios to place soldiers permanently to protect the trunk lines. The Spanish "war of blood and fire" (guerra de sangre y fuego) was not effective enough and the Spanish turned to a strategy of "peace by purchase," followed by peaceful Christian evangelization of the indigenous.[14] The frontier institutions of the presidio and the Christian mission complex became standard crown-supported ways to establish and maintain Spanish control in northern Mexico.

Establishment of a standing military, 18th c.

In the eighteenth century, the rise of rival European empires, particularly the British, threatened Spanish control of its lucrative overseas colonies. The 1762 British capture of Havana, Cuba and Manila, the Philippines in the Seven Years' War, prompted the Spanish crown to protect its colony of Mexico by establishing a standing military. The external military threat was real, but in order to establish a military, Spanish and colonial elites had to overcome the fear of arming large numbers of lower-class non-whites. Given the small number of Spaniards available for military service and the large-scale external threat, there was no alternative to enlisting dark-skinned plebeians into part-time militias or a standing military. Indians were exempt from military service, but mixed-race casta men were part of companies and there were some light- and dark-skinned Afro-Mexican companies.[15]

In the eighteenth century, the Bourbon regime had introduced practices and reforms that systematically excluded elite American-born Spaniards from holding high civil or ecclesiastical office. There were fewer visible routes to status and privilege for these men. The establishment of the military provided such a route to recognition with the establishment of the fuero militar, the privilege of being tried before a military rather than a civilian or criminal court, no matter what the offense. Viceroy Branciforte saw the fuero as a way of attracting wealthy American-born Spaniards to the military. Many of them donated large sums to create militias, with themselves as the ranking member, funding the purchase of arms, uniforms, and equipment. The local city councils cabildos, nominated wealthy and socially prominent estate owners to be officers. What was unusual about the fuero militar from fueros of other groups was its extension to enlisted men and not just officers. The crown was concerned that such an extension to the lower ranks would the military a haven for miscreants.[16][17]

Mexican War of Independence, 1810-1821

Events in the late 18th and early 19th centuries may be best summed as to have caused the fight against the Spanish. The Criollos, or American-born rather than Spaniards born in Spain (Peninsulares) had since the eighteen-century Bourbon reforms been passed over for high posts in the civil and ecclesiastical structures; mixed-race castas and indigenous peoples were legally lower in standing with unequal access to justice and usually lived in dire poverty. Spain's debility at the start of the Napoleonic Wars, and an inability to control itself during its French occupation allowed several creole rebels to take advantage of the situation. Thus, leaders such as Simón Bolívar, José de San Martín and Antonio José de Sucre started revolutions throughout Latin America to attain independence.

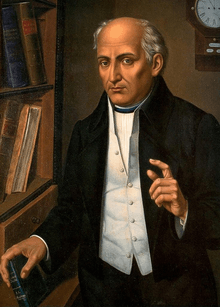

Mexico's War of Independence was less straightforward than the independence movements in most of Spanish South America. In 1808 Peninsulares in Mexico City ousted the viceroy, Iturrigaray, whom they considered too accommodating to creoles' demands. In 1810 a conspiracy of creoles for independence, plotted a rising against the royal government. When it was discovered, secular priest Miguel Hidalgo called to his rural parishioners in the pueblo of Dolores for an uprising. The Grito de Dolores that had denounced bad government touched off a massive uprising by mixed-race castas and indigenous tens of thousands of unorganized followers of Hidalgo. Creole elites who had toyed with the idea of political independence rapidly withdrew their support as their property and persons were targeted for violence.

The viceroy was slow to mobilize a military response to the Hidalgo revolt. Troops had been moved to Mexico City and units suspected of sympathies for independence were demobilized. The followers of Hidalgo rapidly took San Miguel, Guanajuato, Valladolid, and Guadalajara, to the north and northwest of Mexico City. Some regional forces were caught up with the rebels in Querétaro and Michoacán. "Militiamen with their arms and wearing their Spanish uniforms marched with Hidalgo's masses. Some criollo officers, mostly provincial sublieutenants, lieutenants, and captains, attempted to discipline and organize the inchoate popular movement."[18] The larger story, however, was that the vast majority of the royalist army remained loyal to the crown. When Félix Calleja took command of the royal forces, he won a series of decisive victories against Hidalgo's insurgent forces.

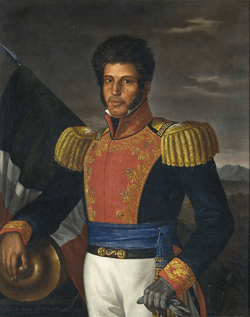

The large-scale insurgency for independence in the north was suppressed, but insurgents in southern Mexico, particularly under Vicente Guerrero turned to guerrilla warfare. Royal troops were less able to win decisive victories and the insurgency remained at a stalemale until the end of the decade. The political situation changed in Spain with a major impact on the situation in New Spain. Spanish liberals staged a coup against the absolutist monarch and for three years sought to implement the liberal constitution of 1812. In Mexico, conservatives saw this turn of events as highly unsettling and considered political independence now an option. Royalist army officer Agustín de Iturbide drafted the Plan of Iguala, calling for political independence, a constitutional monarchy, equality, and Catholicism as its core principles. He persuaded insurgent leader Guerrero to join them. Together they formed the Army of the Three Guarantees, which triumphantly marched into Mexico City in 1821. Independence from Spain was first proclaimed by Hidalgo in 1810, but it was not a political reality until 1821, when the last Spanish viceroy Juan O'Donojú signed the Treaty of Córdoba, 16 September in Córdoba, Veracruz.

Félix María Calleja, Royalist general who defeated Miguel Hidalgo in battle

Félix María Calleja, Royalist general who defeated Miguel Hidalgo in battle Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, "father of Mexican independence" for his 1810 insurgency

Father Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, "father of Mexican independence" for his 1810 insurgency Father José María Morelos, Mexican insurgent. 1812 portrait, now in Chapultepec Castle in the Museo Nacional de Historia.

Father José María Morelos, Mexican insurgent. 1812 portrait, now in Chapultepec Castle in the Museo Nacional de Historia. Vicente Guerrero, insurgent general who signed onto the Plan of Iguala

Vicente Guerrero, insurgent general who signed onto the Plan of Iguala Agustín de Iturbide, royalist officer turned insurgent leader. Author of the Plan of Iguala, Emperor Agustín I, forced to abdicate and later shot returning to Mexico

Agustín de Iturbide, royalist officer turned insurgent leader. Author of the Plan of Iguala, Emperor Agustín I, forced to abdicate and later shot returning to Mexico- General Guadalupe Victoria, first president of the Republic of Mexico

- Antonio López de Santa Anna came to dominate Mexico for thirty years

First Mexican Empire and its overthrow, 1822-1823

In 1821 Agustín de Iturbide, a former Spanish general who switched sides to fight for Mexican independence, proclaimed himself emperor – officially as a temporary measure until a member of European royalty could be persuaded to become monarch of Mexico (see First Mexican Empire for more information). A revolt against Iturbide in 1823 established the United Mexican States. In 1824 Guadalupe Victoria became the first president of the new country; his given name was actually Félix Fernández but he chose his new name for symbolic significance: Guadalupe to give thanks for the protection of Our Lady of Guadalupe, and Victoria, which means Victory.

The Plan de Casa Mata was formulated to abolish the monarchy and to establish a republic. In December 1822, Antonio López de Santa Anna and Guadalupe Victoria signed the Plan de Casa Mata on February 1, 1823, as a start of their efforts to overthrow Emperor Agustín de Iturbide.

In May 1822, using military riots and pressures, Iturbide had taken the power and designated himself Emperor, initiating his government in fight with the Congress. Later he dissolved Congress and ordered opposing deputies to jail.

Several insurrections arose in the provinces and were later crushed by the army. Veracruz was spared due to an agreement between Antonio López de Santa Anna and the rebel general Echávarri.

By agreement of both heads the Plan de Casa Mata was proclaimed on February 1, 1823. This plan did not recognize the Empire and requested the meeting of a new Constituent Congress. The insurrectionists sent their proposal to the provincial delegations and requested their adhesion to the plan. In the course of only six weeks the Plan de Casa Mata had arrived at remote places, like Texas, and almost all the provinces had been united to the plan.

Early Republic

Spanish attempts to reconquer Mexico, 1821-29

Spain did not reconcile itself to the loss of its valuable colony, refusing to acknowledge the Treaty of Cordoba. Spain initiated military efforts to reconquer it during the 1820s. A criollo military officer who emerged as a hero of Mexican nationalism was Antonio López de Santa Anna. In defending Mexico's independence, Santa Anna lost a leg in battle, which became the visible symbol of his sacrifices for the nation. He capitalized on this reputation to forward his political career. The early post-independence period is often called the Age of Santa Anna.

The attempts to reconquer Mexico were not successful, but not until 28 December 1836 did Spain recognize the independence of Mexico. The Santa María–Calatrava Treaty was signed in Madrid by the Mexican Commissioner Miguel Santa María and the Spanish state minister José María Calatrava.[19][20]

Pastry War, 1838

In 1838 a French pastry cook, Monsieur Remontel, claimed his shop in the Tacubaya district of Mexico City had been ruined by looting Mexican officers in 1828. He appealed to France's King Louis-Philippe (1773–1850). Coming to its citizen's aid, France demanded 600,000 pesos in damages. This amount was extremely high when compared to an average workman's daily pay, which was about one peso. In addition to this amount, Mexico had defaulted on millions of dollars worth of loans from France. Diplomat Baron Beffaudis gave Mexico an ultimatum of paying, or the French would demand satisfaction. When the payment was not forthcoming from president Anastasio Bustamante (1780–1853), the king sent a fleet under Rear Admiral Charles Baudin to declare a blockade of all Mexican ports from Yucatán to the Rio Grande, to bombard the coastal fortress of San Juan de Ulúa, and to seize the port of Veracruz. Virtually the entire Mexican Navy was captured at Veracruz by December 1838. Mexico declared war on France. The French withdrew in 1839.

Texas Revolution, 1835-1836

.jpg)

The Texan struggle for independence marked the beginning of a conflict with the modern U.S. state of Texas, and its independence from Mexico and the state of Coahuila y Tejas. Battles associated with the conflict with Texas include the Alamo, where federal troops led by Antonio López de Santa Anna defeated the Texans, and the Battle of San Jacinto, which allowed secession to take place.

Revolts erupted throughout several states after Santa Anna's rise to power. The revolution in Texas began in Gonzales, Texas, when Santa Anna ordered troops to go there and disarm the militia. The war leaned heavily in favor of the rebels after they had won the Battle of Gonzales, captured the fort La Bahía, and successfully captured San Antonio (commonly called Béxar at the time). The war ended in 1836 at the Battle of San Jacinto (about 20 miles east of modern-day Houston) where General Sam Houston led the Texas army to victory over a portion of the Mexican Army led by Santa Anna, who was captured shortly after the battle. The conclusion of the war resulted in the creation of the Republic of Texas, a nation that teetered between collapse and invasion from Mexico until it was annexed by the United States of America in 1845.

Mexican–American War, 1846-1848

The dominant figure of the second quarter of 19th century Mexico was the dictator Antonio López de Santa Anna. During this period, many of the territories in the north were lost to the United States. Santa Anna was the nation's leader during the conflict with Texas, which declared itself independent in 1836, and during the Mexican–American War (1846–48). One of the memorable battles of the U.S. invasion of 1847 was when a group of young Military College cadets (now considered national heroes) fought to the death against a large army of experienced soldiers in the Battle of Chapultepec (September 13, 1847). Ever since this war many Mexicans have resented the loss of much territory, some by means of coercion, and more territory sold cheaply by the dictator Santa Anna (allegedly) for personal profit.

After the declaration of war, U.S. forces invaded Mexican territory on several fronts. In the Pacific, the U.S. Navy sent John D. Sloat to occupy California and claim it for the U.S. because of concerns that Britain might also attempt to occupy the area. He linked up with Anglo colonists in Northern California controlled by the U.S. Army. Meanwhile, U.S. army troops under Stephen W. Kearny occupied Santa Fe, New Mexico, and Kearny led a small force to California where, after some initial reverses, he united with naval reinforcements under Robert F. Stockton to occupy San Diego and Los Angeles.

The main force led by Taylor continued across the Rio Grande, winning the Battle of Monterrey in September 1846. President Antonio López de Santa Anna personally marched north to fight Taylor but was defeated at the battle of Buena Vista on February 22, 1847. Meanwhile, rather than reinforce Taylor's army for a continued advance, President Polk sent a second army under U.S. general Winfield Scott in March, which was transported to the port of Veracruz by sea, to begin an invasion of the country's heartland. Scott won the Siege of Veracruz and marched toward Mexico City, winning the battles of Cerro Gordo and Chapultepec and occupying the capital.

The Treaty of Cahuenga, signed on January 13, 1847, ended the fighting in California. The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, signed on February 2, 1848, ended the war and gave the USA undisputed control of Texas as well as California, Nevada, Utah, and parts of Colorado, Arizona, New Mexico, and Wyoming. In return, Mexico received $18,250,000 or the equivalent of $627,482,629 in today's dollars, total for the cost of the war.

Caste War of Yucatán, 1847-1901

The Caste War lasted from 1847 to 1901, and began as a war of the Maya against the Yucatecos, a colloquial name for people of non-Maya ancestry that settled in the region. Nowadays "Yucatecos" is the demonym given to people who live in the Yucatán state.

The Maya revolt reached its peak of success in the spring of 1848 by driving the Europeans from all the Yucatán Peninsula, with the exception of the walled cities of Campeche and Mérida and a stronghold between the road from Mérida and Sisal.

The Yucatecan governor Miguel Barbachano had prepared a decree for the evacuation of Mérida, but was apparently delayed in publishing it by the lack of suitable paper in the besieged capital. The decree became unnecessary when the republican troops suddenly broke the siege and took the offensive with major advances. The majority of the Maya troops, not realizing the unique strategic advantage of their situation, had left the lines to plant their crops, planning to return after planting.

Yucatán had considered itself an independent nation, but during the crisis of the revolt had offered sovereignty to any nation that would aid in defeating the Indians. The Mexican government was in a rare position of being cash rich from payment by the United States under the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo for the territory taken in the Mexican–American War, and accepted Yucatán's offer. Yucatán was officially reunited with Mexico on 17 August 1848. European Yucateco forces rallied, aided by fresh guns, money, and troops from Mexico, and pushed back the Maya from more than half of the state.

In the 1850s a stalemate developed, with the Yucatecan government in control of the north-west, and the Maya in control of the south-east, with a sparsely populated jungle frontier in between.

In 1850, the Maya of the south east were inspired to continue the struggle by the apparition of the "Talking Cross". This apparition, believed to be a way in which God communicated with the Maya, dictated that the War continue. Chan Santa Cruz (Small Holy Cross) became the religious and political center of the Maya resistance and the rebellion came to be infused with religious significance. Chan Santa Cruz also became the name of the largest of the independent Maya states, as well as the name of the capital town. The followers of the Cross were known as "Cruzob".

The government of Yucatán first declared the war over in 1855, but hopes for peace were premature. There were regular skirmishes, and occasional deadly major assaults into each other's territory, by both sides. The United Kingdom recognized the Chan Santa Cruz Maya as a de facto independent nation, in part because of the major trade between Chan Santa Cruz and British Honduras.

Negotiations in 1883 led to a treaty signed on 11 January 1884 in Belize City by a Chan Santa Cruz general and the vice-Governor of Yucatán recognizing Mexican sovereignty over Chan Santa Cruz in exchange for Mexican recognition of Chan Santa Cruz leader Crescencio Poot as "Governor" of the "State" of Chan Santa Cruz, but the following year there was a coup d'état in Chan Santa Cruz, and the treaty was declared cancelled.

Era of the Liberal Reform

This period was the only one in the nineteenth century with civilian control of the government, but it was not a peaceful era, with a civil war and the foreign invasion of the French and monarchy supported by Mexico's Conservatives, followed by the restoration of the Liberal Republic.

Overthrow of Santa Anna in the Revolution of Ayutla, 1855

The Revolution of Ayutla was an 1854 plan to overthrow the Santa Anna regime by the revolutionary Benito Juárez during his exile in New Orleans, Louisiana. The revolution sustained much support among intellectuals. This tension led to the final resignation of Santa Anna in 1855. Juan Álvarez led a provisional government after Santa Anna's final resignation, and the Revolution of Ayutla became one of the leading factors in the Reform War.

The Reform War, 1857-1860

In 1855 Ignacio Comonfort, leader of the self-described Moderates, was elected president. The Moderados tried to find a middle ground between the nation's Liberals and Conservatives. During Comonfort's presidency a new Constitution was drafted. The Constitution of 1857 sought to establish equality before the law, so that the abolition of fueros, the special privileges of corporate groups, were abolished, including the fuero militar. Such reforms were unacceptable to the leadership of the clergy and the Conservatives, Comonfort and members of his administration were excommunicated and a revolt was declared. This led to the War of Reform, from December 1857 to January 1861. This civil war became increasingly bloody and polarized the nation's politics. Many of the Moderados came over to the side of the Liberales, convinced that the great political power of the Church needed to be curbed. For some time the Liberals and Conservatives had their own governments, the Conservatives in Mexico City and the Liberals headquartered in Veracruz. The war ended with Liberal victory on the battlefield, and Liberal president Benito Juárez moved his administration to Mexico City. But that was not the end of the conflict between Liberals and Conservatives, which was to carry on through another seven years.

French Intervention, 1862-1867

When Juárez repudiated the debts incurred by the rival conservative Mexican government in 1861, Mexican conservatives and European powers, especially France took the opportunity to place a European monarch as head of state in Mexico. The French sent an invading army in 1862, while the U.S. was engaged in its civil war (1861–65).

Although the French, then considered one of the most efficient armies of the world, suffered an initial defeat in the Battle of Puebla on May 5, 1862 (now commemorated as the Cinco de Mayo holiday) they eventually defeated loyalist government forces led by General Ignacio Zaragoza and enthroned Maximilian as Emperor of Mexico. Maximilian of Habsburg favored the establishment of a limited monarchy sharing powers with a democratically elected congress. This was too liberal to please the Conservatives, while the liberals refused to accept a monarch, leaving Maximilian with few enthusiastic allies within Mexico. When the Civil War ended in 1865, the United States sent military aid to Juárez's government. In 1867, the French withdrew their military support of Maximilian, who refused the opportunity to return to Europe. He was captured and executed on the Cerro de las Campanas, Querétaro, by the forces loyal to President Benito Juárez.

Restored Republic under Juárez and the overthrow of Lerdo

Juárez's republic was restored. However, liberal General Porfirio Díaz, a hero of the Battle of Puebla during the French Intervention, challenged civilian liberal president Benito Juárez following fall of the French empire of Maxilimilian Hapsburg that had been propped up by the French government. After Juárez died in office of a heart attack, Sebastián Lerdo de Tejada became president. Díaz then challenged him when Lerdo ran for election; Díaz issued the Plan of Tuxtepec, successfully overthrowing him in 1876.

Porfiriato (1876-1911)

General Díaz came to the presidency by coup, and then there was an election after the fact. The thirty years of his presidency, known as the Porfiriato, was a self-proclaimed era of "Order and Progress." Díaz brought order, sometimes through brutal suppression of uprisings, that gave entrepreneurs confidence to invest in Mexico's modernization. In 1880 at the end of his term, Díaz stepped away from the presidency, and his fellow liberal general, Manuel González, became president of Mexico. In 1884, Díaz returned to the presidency, where he remained in continuous power until 1911. Díaz saw the regular army as a potential threat to his vision of Mexico and his own regime; its budget absorbed a huge amount of the national budget. "He reduced the size of the officer corps and the total strength of the army from a theoretical 30,000 to 20,000."[21] He began to expand the size and role of the elite rural military police, the rurales, placing them under his direct control. The Army remained , but it was increasingly an aging and less efficient or effective fighting force. Díaz was a modernizing, liberal authoritarian, who sought Mexico's development through "order and progress." Peace in Mexico was the key to attracting foreign investment. A major infrastructure project that facilitated that was the construction of a railway network in Mexico, with telegraph lines built along track beds. Rural policemen and their horses could be put on trains and sent to remote areas to suppress rebellions and re-establish order.[22]

Mexican Revolution 1910-1920

The Mexican Revolution came about as a protest against the aging dictator, Porfirio Díaz, and to quell social and economic injustices as found under his authoritarian regime. In 1910 the 80-year-old Díaz reversed his publicly-stated decision not to run for reelection for another term as president. He thought he had long since eliminated any serious opposition at home, including General Bernardo Reyes. He did not consider his nephew, General Félix Díaz as his successor, nor his own son, also a military officer, so did not seek to establish a family dynasty. However, Francisco I. Madero, a civilian from a rich land-owning family, challenged him for the presidency, and quickly gathered popular support. Díaz jailed Madero and fraudulent elections were held.

When the official election results were announced, it was declared that Díaz had won reelection almost unanimously, with Madero receiving only a few hundred votes in the entire country. This fraud by the Porfiriato was too blatant for the public to swallow, and riots broke out. Madero prepared a document known as the Plan de San Luis Potosí, in which he called the people to take their weapons and fight against the illegitimate government of Porfirio Díaz. There was no massive uprising November 20, 1910, but rebellions in Morelos and in northern Mexico, especially by Pascual Orozco and his then-subordinate Pancho Villa defeated the Federal Army, capturing the strategic border town of Ciudad Juárez, forcing Díaz to resign in May 1911. The Treaty of Ciudad Juárez called for Díaz's resignation and exile, an interim presidency pending new elections, and the retention of the Federal Army. Rebels who had ousted Díaz were to be demobilized. For those rebels, this political transition retaining to Federal Army and practically the whole leadership of Díaz's administration was dismaying. Elections were scheduled for the fall, with Madero campaigning actively. In the meantime, the Federal Army under General Victoriano Huerta was directed that summer to Morelos to suppress rebels led by Emiliano Zapata. Elections were held in the fall, with Madero overwhelmingly elected. Once in office, however, the inexperienced civilian politician was unable to govern effectively. A few days after his inauguration, Zapata and fellow leaders in Morelos issued the Plan of Ayala, declaring themselves in rebellion against the Madero government for not implementing land reform. Zapatistas continued to be in rebellion against every subsequent government that decade. Northern rebel Pascual Orozco, a former muleteer, had led rebels in the north, bringing Madero to power. Madero insultingly appointed him a commander of a local rural police force, while keeping the Federal Army commanders he had defeated in power. In 1912 Orozco rose in rebellion against Madero. Madero sent General Huerta to suppress it. General Reyes and General Félix Díaz rose in rebellion and were jailed. Despite their incarceration in separate prisons, they hatch a plot, with the support of the U.S. Ambassador, to overthrow Madero. General Huerta secretly joined the plot. In February 1913 Reyes and Díaz were freed from jail, and Mexico City came under bombardment by rebels in what is known as the Ten Tragic Days. Huerta seized command of the rebels, arrested Madero and his vice president and forced to resign. Madero and he were murdered. Huerta became president of Mexico. The reaction to this was a rising in the north of Mexico, with the Governor of Coahuila state declaring the Huerta regime illegitimate and becoming the "First Chief" of the Constitutionalist Army. Two brilliant natural soldiers, Pancho Villa and Alvaro Obregón, rose to command armies that soundly defeated Huerta's Federal Army. Huerta resigned in July 1914, and the Federal Army dissolved. Zapata had continued guerrilla warfare in Morelos.

With the forces of reaction defeated and the Federal Army gone, the revolutionary winners failed to reach agreement on how power would now exercised. Civil war was the result. Pancho Villa broke with First Chief of the Constitutionalists, Carranza, and went into a loose alliance with Zapata. Constitutionalist General Obregón remained loyal to Carranza and defeated Villa in the Battle of Celaya in 1915. Villa's Northern Division shrank to practically nothing. Carranza took power and held elections. Revolutionaries drafted a new constitution in 1917, enshrining the Mexican government's power over land and natural resources as well as labor rights. Zapata remained in rebellion in Morelos, and Carranza ordered his assassination in 1919. Obregón returned to his home state of Sonora, to await developments when elections were to be held in 1920. When Carranza chose a civilian, Mexico's Ambassador to the U.S., revolutionary generals viewed Carranza as trying to prolong his power with a puppet. Three generals from Sonora, including Obregón, rebelled against Carranza, ousting him. In the 1920, Constitutionalist Army General Álvaro Obregón became president of Mexico. He accommodated all elements of Mexican society except the most reactionary clergy and landlords, and successfully catalyzed social liberalization, particularly in curbing the role of the Catholic Church, improving education and taking steps toward instituting women's civil rights.

Role of the soldaderas

Soldaderas were women soldiers sent to combat among the men during the Mexican Revolution against the conservative Díaz regime to fight for freedoms. Many of these women led ordinary lives, but had taken arms during the time to seek better conditions and rights. Among the soldaderas Dolores Jiménez y Muro and Hermila Galindo are often considered heroines to Mexico today. Today, references to "La Adelita" are made as a symbol of pride among Mexican women. La Adelita was the title of one of the most famous corridos (folk songs) to come out of the Revolution, in which an unnamed revolutionary sang of his undying love for the soldadera Adelita.

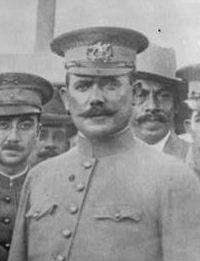

_Pascual_Orozco._(21879503251).jpg) General Pascual Orozco (right), who defeated Diaz's Federal Army in Ciudad Juárez in 1911, and helped bring and Francisco I. Madero (left) to the presidency in 1911. Orozco revolted against Madero in 1912

General Pascual Orozco (right), who defeated Diaz's Federal Army in Ciudad Juárez in 1911, and helped bring and Francisco I. Madero (left) to the presidency in 1911. Orozco revolted against Madero in 1912 Federal Army General Victoriano, who led the coup d'etat against Madero, setting off a civil war. With his defeat, the Federal Army was dissolved

Federal Army General Victoriano, who led the coup d'etat against Madero, setting off a civil war. With his defeat, the Federal Army was dissolved.jpg) Venustiano Carranza, "First Chief" of the Constitutionalist Army, who led the victorious northern faction of the Mexican Revolution

Venustiano Carranza, "First Chief" of the Constitutionalist Army, who led the victorious northern faction of the Mexican Revolution General Pancho Villa, who led the Division of the North in the Constitutionalist Army, later breaking with it

General Pancho Villa, who led the Division of the North in the Constitutionalist Army, later breaking with it General Alvaro Obregón, who remained loyal to Carranza, leader of the Constitutionalists

General Alvaro Obregón, who remained loyal to Carranza, leader of the Constitutionalists General Emiliano Zapata, revolutionary leader of the Liberating Army of the South, allied loosely with Villa in 1915, but was in continuous rebellion against incumbent regimes until his assassination by an agent of Carranza in 1919

General Emiliano Zapata, revolutionary leader of the Liberating Army of the South, allied loosely with Villa in 1915, but was in continuous rebellion against incumbent regimes until his assassination by an agent of Carranza in 1919 Soldaderas, women participants in the Mexican Revolution

Soldaderas, women participants in the Mexican Revolution

World War I Era

With the Revolution still being fought, Mexico remained neutral during the First World War. In addition to the internal conflict of the Revolution, it also experienced external pressures during the war, the most notable incidents being the Tampico Affair, the Pancho Villa Expedition, and the Zimmermann Telegram.

Tensions with the United States resulted in direct military conflict in several instances of varying severity. In addition, while Mexico rejected Germany's overtures to join in war on the United States, a telegram intercepted by the United Kingdom in 1917 hastened U.S. entry into World War I.

On April 9, 1914, officials in the port of Tampico, Tamaulipas, arrested a group of U.S. sailors — including, crucially, at least one taken from on board a ship's boat flying the U.S. flag, and thus from U.S. territory. Mexico's failure to apologize in the terms demanded led to the U.S. navy's bombardment of the port of Veracruz and the occupation of that city for seven months.

In 1916, Pancho Villa crossed the U.S. border and attacked the town of Columbus, New Mexico; this was the sole invasion by a foreign armed corps of the continental U.S. in the 20th century. This raid led the U.S. to send a force under General John Pershing into Mexico, which spent 11 months unsuccessfully chasing him in the punitive Pancho Villa Expedition (March 1916 – February 1917).

The Zimmermann Telegram affair of January 1917, while it did not lead to direct U.S. intervention, also took place against the backdrop of the Constitutional Convention and exacerbated tensions between the US and Mexico. However, following the 27 August 1918 Battle of Ambos Nogales, a skirmish between US Army and Villista troops, it was alleged that the bodies of two Germans were found among the dead. Since the United States and the German Empire were at war at the time, it is widely believed that the Germans were agents provocateurs tasked with instigating attacks against the United States.-

Era of the Post Revolution, 1920-1946

The period after the overthrow of Venusiano Carranza by Sonora revolutionary generals, particularly Alvaro Obregón He initiated a twenty-five year period of revolutionary generals in the presidency. Each one systematically curtailed the power of the military.

Postrevolutionary military

Starting in 1920 until the election of 1946, Mexico's postrevolutionary presidents were all revolutionary generals. Three generals from Sonora, Alvaro Obregón, Plutarco Elías Calles, and Adolfo de la Huerta overthrew civilian president Venustiano Carranza under the Plan of Agua Prieta. Carranza had attempted to impose a nobody, Ignacio Bonillas as his successor in 1920. Carranza died while trying to flee the country, and De la Huerta was installed as interim president, pending elections. Obregón was elected in 1920, serving a full four-year term. When Obregón chose Calles rather than De la Huerta as his successor, De la Huerta led an unsuccessful rebellion in 1923. Calles's anti-clerical policies caused the outbreak of religious warfare, the Cristero War. The constitution was changed to allow the re-election of a president if the terms were not continuous, allowing Obregón to run again in the 1928 election. Obregón won, but was assassinated by a Catholic fanatic before taking office. Calles could not directly serve as president, but brokered a solution to presidential succession by founding the Partido Nacional Revolucionario (PRN), the precursor of óe candidate for the PRN. When Cárdenas move out of the shadow of Calles, Calles put him on an airplane to exile in the U.S. In 1936, Cárdenas reorganize the dominant party, renaming it the Partido Revolucionario Mexicano, with sectors of members by occupation. The Mexican National Army became of the four sectors, making it dependent on the PRM for patronage and privilege. Cárdenas implemented some radical policies, including land reform in Mexico as well as expropriation of foreign-owned petroleum in 1938. Cárdenas chose the moderate Manuel Avila Camacho, wryly known as the "unknown soldier," for his undistinguished revolutionary record. Retired revolutionary general Juan Andreu Almazán ran for the presidency, but in violent and likely fraudulent election, Avila Camacho was declared the winner. Almazán sought support from the U.S. and considered fomenting a rebellion, but in the end he attended Avila Camacho's inauguration. In 1946, the party chose Miguel Alemán Valdés, the son of a revolutionary general, to be its candidate. The PRM became the Institutional Revolutionary Party in 1946, no longer having a sector for the army. No military men sought office Miguel Henríquez Gunzmán revolt in 1952. There were no more rebellions or attempted coups. The long history of the Mexican military as a political force was over. "The armed forces had been disciplined, unifed, and subordinated to the civilian power... The consolidation of civilian supremacy over the armed forces in the 1950s established conditions for a particularly stable pattern of civilian-military relations."[23]

Revolutionary general and President of Mexico, 1920–24

Revolutionary general and President of Mexico, 1920–24.jpg) Plutarco Elías Calles, Revolutionary general and President 1924-28; power behind the presidency in the Maximato, 1928–34

Plutarco Elías Calles, Revolutionary general and President 1924-28; power behind the presidency in the Maximato, 1928–34 General Lázaro46 Cárdenas, revolutionary general and president 1934-40

General Lázaro46 Cárdenas, revolutionary general and president 1934-40 Manuel Avila Camacho, revolutionary officer and president of Mexico 1940-46

Manuel Avila Camacho, revolutionary officer and president of Mexico 1940-46 Adolfo de la Huerta, revolutionary general and interim president of Mexico, 1920, who led a failed rebellion in 1923 against Calles's candidacy

Adolfo de la Huerta, revolutionary general and interim president of Mexico, 1920, who led a failed rebellion in 1923 against Calles's candidacy- José Gonzalo Escobar, revolutionary general who led a failed rebellion in 1929

- , Juan Andreu Almazán, revolutionary general who challenged Avila Camacho for the presidency in 1940

Cristero War, 1926-1929

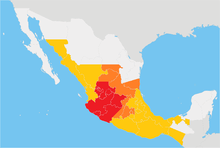

Large-scale outbreaks Moderate outbreaks Sporadic outbreaks

The Cristero War (also known as La Cristiada), was the last large-scale uprising in Mexico after the end of the military phase of the Mexican Revolution in 1920. There are estimates of 100,000 Mexican army troops combating 50,000 Cristeros, with nearly 57,000 government troops killed and 30-50,000 Cristeros killed. An estimated 250,000, largely noncombats, fled, many to the U.S. The conflict stemmed from former revolutionary general Plutarco Elías Calles's implementation of the anticlerical elements of the 1917 Mexican Constitution. An experienced general in the Victoriano Huerta regime, Enrique Gorostieta led Cristeros. Alvaro Obregón, no friend of the Catholic tChurch, did not see a reason to provoke conflict with it when there were pressing issues for his presidency, such as securing U.S. diplomatic recognition and reining in regional revolutionary generals,

Calles's actions against the Catholic Church and popular religious practice produced significant reaction from the Catholic hierarchy and many men who had fought in the Mexican Revolution. After a period of peaceful resistance, a number of skirmishes took place in 1926. The formal rebellion began on January 1, 1927 with the rebels calling themselves Cristeros because they felt they were fighting for Christ himself. Just as the Cristeros began to hold their own against the federal forces, the rebellion was ended by diplomatic means, in large part due to the efforts of U.S. Ambassador Dwight Whitney Morrow. The legacy of the Cristero War includes that of martyrdom, as several Cristeros, such as José Sánchez del Río and the Blessed Miguel Pro, were considered heroes for sacrificing their lives for the sake of the church. When General Manuel Avila Camacho became president of Mexico in 1940, he declared himself a Christian believer (soy creyente), and armed conflict over religion was at an end.

World War II

With the inauguration of Manuel Avila Camacho, the trend of greater cooperation with the United States accelerated as World War II seemed certain to involve other nations. Mexico broke relations with the Axis Powers following its attack on the U.S. base at Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Mexico extended rights of the U.S. Navy and participated in a Joint Defense Commission with the U.S. The Mexican public was not keen in becoming involved in an international conflict. On 22 May 1942, following the torpedoing of two oil tankers in the Gulf, notably the Potrero del Llano and the Faja de Oro by German U-Boats, Mexico declared itself in a state of war with the Axis powers. Mexico instituted national military service in 1942 as well as civil defense. Former President Lázaro Cárdenas (1934–40) served the Avila Camacho administration as Minister of Defense. Cárdenas was the key negotiator with the U.S. military about "radar surveillance, landing rights, naval patrols, and chains of command."[24][25] The Mexican population was indifferent or hostile to the war, but the institution of conscription was an issue. There were violent protests against conscription. The Mexican government did not send conscripts overseas, which helped quell civil unrest over conscription. But Mexican citizens in the U.S. were drafted in the U.S. Army, sustaining a high casualty rate.[26]

The fighting unit in the Mexican military was the Escuadrón 201, also known as the Aztec Eagles saw combat in World War II. This group comprised more than 300 volunteers, who trained in the United States to fight against Imperial Japan. It was the first Mexican military unit trained for overseas combat.[27][28]

Although most countries in the Western Hemisphere eventually entered the war on the Allies' side, Mexico and Brazil were the only Latin American nations that sent troops to fight overseas during World War II. The cooperation of Mexico and the United States in World War II helped bring about reconciliation between the two countries at the leadership level.[29]

In the civil arena, the Bracero Program gave the opportunity for many thousands of Mexicans to work in the US in support of the Allied war effort. This also granted them an opportunity to gain US citizenship by enlisting in the military.

Post World War II

Mexico-Guatemala Conflict, 1958

On December 31, 1958, Mexican fishing boats were attacked by the Fuerza Aérea Guatemalteca (FAG) in the territorial waters of Guatemala. Three fishermen were killed and fourteen injured. Ten of the survivors were subjected to interrogation by the Guatemalan military. The situation caused a temporary termination of diplomatic relations and trade between Mexico and Guatemala, a border bridge was destroyed and the two countries put their militaries on alert.

1994 Zapatista Rebellion in Chiapas

One recent event in the military history of Mexico is that of the Zapatista Army of National Liberation, which is an armed rebel group that claims to work to promote the rights of the country's indigenous peoples. The Zapatistas had the initial goal of overthrowing the federal government. Short armed clashes in Chiapas ended two weeks after the uprising and there have been no full-scale confrontations ever since. The federal government instead pursued a policy of low-intensity warfare with para-military groups in an attempt to control the rebellion, while the Zapatistas developed a media campaign through numerous newspaper comunicados and over time a set of six "Declarations of the Lacandonian Jungle", with no further military or terrorist actions on their part. A strong international Internet presence has prompted the adherence to the movement of numerous leftist international groups.

President Ernesto Zedillo (1994–2000) refused most of the demands of the rebels.

Hurricane Katrina, 2005

In September 2005 Mexican army convoys traveled to the U.S. to help in the Hurricane Katrina relief effort. Mexican army convoys and a navy ship laden with food, supplies and specialists traveled to the United States including military specialists, doctors, nurses and engineers carrying water treatment plants, mobile kitchens, food and blankets. The convoy represents the first Mexican military unit to operate on U.S. soil since 1846, when Mexican troops briefly marched into Texas, which had separated from Mexico and joined the United States. All of the convoy's participants were unarmed.

Mexican Dirty War

Mexican Drug War

The Mexican military has participated in efforts against drug trafficking. The Operaciones contra el narcotrafico (Operations against drug trafficking), for example, describes its purpose in regards to "the performance of the Mexican Army and Air Force in the permanent campaign against the drug trafficking is sustained properly in the faculties that the Executive of the Nation grants to him, the 89 Art. Fracc. VI of the Constitution of the Mexican United States, when indicating that it is faculty of the President of the Republic to have the totality of the permanent Armed Forces, that is of the terrestrial Army, Navy military and the Air Force for the inner and outer security of the federation."

U.N. Peacekeeping, 2014

Mexico has deployed troops for the United Nations peacekeeping efforts.[30][31]

Border security

The government of Andrés Manuel López Obrador established the Mexican National Guard in 2019, which has been involved with border security.[32]

Timeline

- 1519: Hernán Cortés lands at Veracruz. In 1521 Cortés and his indigenous allies conquer Tenochtitlán, the Aztec capital.

- 1808: Napoleon dethrones the Spanish king, Charles IV, stimulating political unrest throughout Spain's empire.

- 1810–c. 1821: During wars of independence that pit Mexicans against one another as well as the forces of Spain, over 12 percent of the Mexican population dies. Independence is achieved under the 1821 Plan of Iguala, which promises equality for citizens and preserves the privileges of the Catholic Church.

- 1835: Rebels seeking independence for Texas fight the regular army at the Alamo. In 1836 the Texas Republic becomes independent.

- 1837–1841: Revolts favoring federalism over the centralizing constitution imposed by Antonio López de Santa Anna in 1836 occur in much of Mexico.

- 1845: The United States annexes Texas.

- 1846–1848: Mexico and the United States are at war. In the resulting treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo, Mexico recognizes the loss of Texas and cedes parts or all of what are now the U.S. states of New Mexico, Arizona, Utah, Colorado, Nevada, Montana, and California to the United States.

- 1847: The start of the Caste War.

- 1854: Mexico sells 77,700 km² (nearly 30,000 square miles) of northern Sonora and Chihuahua to the United States in the Gadsden Purchase.

- 1854–1861: Benito Juárez and other liberals overthrow Santa Anna (Revolution of Ayutla). The liberal reforms they inaugurate encourage division of Indian and church lands into private holdings, subject clergy and military to regular courts, and establish religious freedom.

- 1857: Constitution re-establishes a federal republic and, moving beyond the Constitution of 1824, guarantees the individual rights of free speech, assembly, and press. In 1858–1861 supporters and opponents of the reforms fight the War of the Reform, which ends in liberal victory.

- 1862–1867: The French emperor Napoleon III, in alliance with conservative and proclerical Mexicans, installs Maximilian of Habsburg as emperor of Mexico. On May 5, 1862, loyalist troops defeat Napoleon III's troops at Puebla. (The holiday Cinco de Mayo honors this victory.) In 1867 Juárez's forces defeat and execute Maximilian.

- 1876–1911: The Porfiriato, the authoritarian regime of the longtime president Porfirio Díaz, maintains the liberal economic policies and secularization achieved under Juárez and encourages foreign investment.

- 1901: End of Caste War.

- 1910–1917: Spurred by discontent with Porfirio Díaz regime, regional animosities, and increasing economic inequality in the countryside, rebellions break out in Morelos and Northern Mexico, forcing Díaz's resignation. Francisco Madero maintains the Federal Army as a force, calling for the demobilization of those who brought him to power. With the military coup by General Victoriano Huerta opponents united to oust him. After his ouster, civil war broke out among the revolutionary factions. The Constitutionalist Army defeats Pancho Villa's army, effectively ending the military phase of the Revolution.

- 1914: United States forces occupy the port city of Veracruz for seven months.

- 1916: United States President Woodrow Wilson orders Gen. John Pershing to capture guerrilla leader Pancho Villa after Villa's attack on Columbus, New Mexico. For nine months 4,000 American troops search in vain for Villa.

- 1917: The Constitution of 1917 maintains republican and liberal features of the 1824 and 1857 constitutions but also guarantees social rights such as a living wage. It nationalizes mineral resources and prohibits foreign businessmen from appealing to their home governments to protect their property. Amended many times, this constitution remains in force.

- 1926: Conflict over the 1917 Constitution's provisions for separation of church and state leads to nationalization of church property and armed rebellion, which the government suppresses. This period is known as the Cristero War.

- 1942: Mexico enters World War II, on the side of the Allied Powers.

- 1994: The Zapatista rebellion in Chiapas protests the PRI's dominance of political power and the government's indifference to the fate of peasants and indigenous peoples.

See also

References

- Archer, Christon I. “Military: Bourbon New Spain” in ‘’Encyclopedia of Mexico’’. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 898-904

- Krauze, Enrique, Mexico: Biography of Power. New York: HarperCollins 1997, p. 510.

- Archer, Christon I. “Military: 1821-1914” in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 904-910

- Serrano, Mónica. "Military: 1914-1996" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 911

- Krauze, Mexico: Biography of Power, p. 510.

- Marcus, Joyce. "Conquests: Pre-Hispanic Period" in The Oxford Encyclopedia of Mesoamerican Cultures, ed. David Carrasco. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001, vol. 1, pp. 251-254.

- Marcus, "Conquests: Pre-Hispanic Period", p. 252.

- Marcus: "Conquests: Pre-Hispanic Period", p. 252.

- Marcus, Joyce. "Conquests: Pre-Hispanic Period", pp. 252-53.

- Altman, Ida, et al. The Early History of Greater Mexico. Prentice Hall 2003, p. 53, pp. 73-96

- Lockhart, James and Stuart B. Schwartz, Early Latin America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1982, pp. 79-80

- Lockhart and Schwartz, Early Latin America, p. 80

- Altman, Ida. The War for Mexico's West: Indians and Spaniards in New Galicia, 1524-1550. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 2010

- Powell, Philip Wayne. Soldiers, Indians, & Silver: The Northward Advance of New Spain, 1550-1600. Berkeley, California: University of California Press, 1952 (republished 1969)

- Archer, Christon I. "Military: Bourbon New Spain" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, pp. 898-900.

- Archer, "Military: Bourbon New Spain", pp. 901-02

- McAlister, Lyle C. The "Fuero Militar" in New Spain, 1764-1800. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1957.

- Archer, "Military: Bourbon New Spain", p. 903

- "Fechas históricas de México" (in Spanish).

- "Tratado Definitivo de Paz entre Mexico y España" (PDF) (in Spanish).

- Archer, Christon I. "Military: 1821-1914" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 909.

- Vanderwood, Paul. Disorder and Progress: Bandits, Police, and Mexican Development. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1981.

- Serrano, Mónica. "Military: 1914-1996" in Encyclopedia of Mexico. Chicago: Fitzroy Dearborn 1997, p. 911

- Knight, Alan. "The rise and fall of Cardenismo, c. 1930- c.1946" in Mexico Since Independence, Leslie Bethell, ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press 1991.

- Minster, Christopher (April 16, 2018). "Mexican Involvement in World War II". ThoughtCo.com. ThoughtCo. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- Knight, "The rise and fall of Cardenismo," p. 303.

- Aviation History (June 12, 2006). "World War II: Mexican Air Force Helped Liberate the Philippines". HistoryNet.com. World History Group. Retrieved June 4, 2018.

- Knight, "The rise and fall of Cardenismo" pp. 302-03.

- Knight, "The rise and fall of Cardenismo," p. 305.

- "In historic U-turn, Mexico to join U.N. peacekeeping missions". Reuters. Reuters. September 24, 2014. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- "IContributors to UN Peacekeeping Operations by Country and Post" (PDF). United Nations Peacekeeping. United Nations. April 30, 2018. Retrieved June 5, 2018.

- National Guard of Mexico website (in Spanish)

Further reading

- Archer, Christon I. The Army in Bourbon Mexico, 1760-1810. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1977.

- Brittsan, Zachary. Popular Politics and Rebellion in Mexico: Manuel Lozada and La Reforma, 1855-1876. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press 2015

- Camp, Roderic Ai. Generals in the Palacio: The Military in Modern Mexico. New York: Oxford University Press 1992.

- DePalo, William A. Jr. The Mexican National Army, 1822-1852. College Station TX: Texas A&M Press 1997.

- Liewen, Edwin. Mexican Militarism: The Political Rise and Fall of the Revolutionary Army. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press 1968.

- McAlister, Lyle C. The "Fuero Militar" in New Spain, 1764-1800. Gainesville: University of Florida Press 1957.

- Serrano, Mónica. "The Armed Branch of the State: Civil-Military Relations in Mexico." Journal of Latin American Studies vol 27. 1995.

- Vanderwood, Paul. Disorder and Progress: Bandits, Police, and Mexican Development. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press 1981.

External links

- William Lamport's Rebellion

- Mexican Revolution

- A Continent Divided: The U.S. - Mexico War, Center for Greater Southwestern Studies, the University of Texas at Arlington

- Mexican–American War

- Wars of Independence

- Mexican Independence

- Mexican War

- Battle of Puebla