Negroid

Negroid (used as both a synonym and superset of Congoid)[1] is a historical grouping of human beings, once purported to be an identifiable race and applied as a political class by another dominant 'non-negroid' culture.[2] The term had been used by forensic and physical anthropologists to refer to individuals and populations that share certain morphological and skeletal traits that are frequent among populations in most of Sub-Saharan Africa and isolated parts of South and Southeast Asia (Negritos).[3][4] Within Africa, a racial dividing line separating Caucasoid physical types from Negroid physical types was held to have existed, with Negroid groups forming most of the population south of the area which stretched from the southern Sahara desert in the west to the African Great Lakes in the southeast.[5]

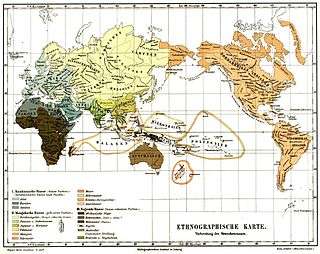

ethnographic map

| Caucasoid: Negroid: Uncertain: | Mongoloid: |

First introduced in the early racial science and anthropometry of the 1780s by members of the Göttingen School of History,[6] Negroid denoted one of the three purported major races of humankind (alongside Caucasoid and Mongoloid).[7] Many social scientists have argued that such analyses are rooted in sociopolitical and historical processes rather than in empirical observation.[8] However, Negroid as a biological classification remains in use in forensic anthropology.[9] The term today is usually considered racist, along with the term it derived from, Negro.

Etymology

Negroid has both Spanish and Ancient Greek etymological roots. It literally translates as "black resemblance" from the Spanish word negro (black), and Greek οειδές -oeidēs, equivalent to -o- + είδες -eidēs "having the appearance of", derivative of είδος eîdos "appearance".[10][11] The earliest recorded use of the term "Negroid" came in 1859.[12] In modern usage, it is associated with populations that on the whole possess the suite of typical Negro physical characteristics.[13]

History of the concept

Origins

Johann Friedrich Blumenbach, a scholar at the then modern Göttingen University developed a concept dividing mankind into five races in the revised 1795 edition of his De generis humani varietate nativa (On the Natural Variety of Mankind). Although Blumenbach's concept later gave rise to scientific racism, his arguments were basically anti-racist,[14] since he underlined that mankind as a whole forms one single species,[15] and points out that the transition from one race to another is so gradual that the distinctions between the races presented by him are "very arbitrary".[16] Blumenbach counts the inhabitants of North Africa among the "Caucasian race", grouping the other Africans as "Ethiopian race". In this context, he names the "Abyssinians" and "Moors" as peoples through which the "Ethiopian race" gradually "flows together" with the "Caucasian race".[17]

In the context of scientific racism

The development of Western race theories took place in a historical situation where most Western nations were still profiting from the enslavement of Africans[18]:524 and therefore had an economical interest in portraying the inhabitants of Sub-Saharan Africa as an inferior race. A significant change in Western views on Africans came about when Napoleon's 1798 invasion of Egypt drew attention to the impressive achievements of Ancient Egypt, which could hardly be reconciled with the theory of Africans being inferior.[18]:526-7 In this context, many of the works published on Egypt after Napoleon's expedition "seemed to have had as their main purpose an attempt to prove in some way that the Egyptians were not Negroes",[18]:525 but belonged to a "Hamitic race", which was seen as a subgroup of the "Caucasian race". Thus the high civilization of Ancient Egypt could be separated from the allegedly inferior African "race".[18]:526

"Perhaps because slavery was both still legal and profitable in the United States ... there arose an American school of anthropology which attempted to prove scientifically that the Egyptian was a Caucasian, far removed from the inferior Negro".[18]:526 In his Crania Aegyptiaca (1844), Samuel George Morton, the founder of anthropology in the United States, analyzed over a hundred intact crania gathered from the Nile Valley, and concluded that the ancient Egyptians were racially akin to Europeans.[19]

Discussions on race among Western scholars during the 19th century took place against the background of the debate between monogenists and polygenists, the former arguing for a single origin of all mankind, the latter holding that each human race had a specific origin. Monogenists based their arguments either on a literal interpretation of the biblical story of Adam and Eve or on secular research. Since polygenism stressed the perceived differences, it was popular among white supremacists, especially slaveholders in the US.[20]

Through craniometry conducted on thousands of human skulls, Morton argued that the differences between the races were too broad to have stemmed from a single common ancestor, but were instead consistent with separate racial origins.[21] In Crania Aegyptiaca, he reported his measurements of internal skull capacity grouped according to Blumenbach's five races, finding that the average capacity of the "Caucasian race" was at the top, and that "Ethiopian" skulls had the smallest capacity, with the other "races" ranging in between.[22] He concluded that the "Ethiopian race" was inferior in terms of intelligence. At his death in 1851, when slavery still existed in the southern United States, the influential Charleston Medical Journal praised him with the words: "We of the South should consider him as our benefactor for aiding most materially in giving to the negro his true position as an inferior race."[23] While a controversy about the correctness of Morton's measurements has been going on since the late 1970s, modern scientists agree that the volume of the skull and intelligence are not related.[24]

| Caucasoid | |

| Congoid | |

| Capoid | |

| Mongoloid | |

| Australoid |

Darwin's landmark work On the Origin of Species, published in 1859, 8 years after Morton's death, significantly changed scientific discourse on the origin of humans. British biologist Thomas Huxley, a strong advocate of Darwinism and a monogenist, counted 10 "modifications of mankind", dividing the native populations of sub-Saharan Africa into the "Bushmen" of the Cape region and the "Negroes" of the central areas of the continent.[25]

By the end of the 19th century, the influential German encyclopaedia, Meyers Konversations-Lexikon, divided humanity into three major races called Caucasoid, Mongoloid, and Negroid, each comprising various sub-races.

Later iterations of the terminology, such as Carleton S. Coon's Origin of Races, placed this theory in an evolutionary context. Coon divided the species Homo sapiens into five groups: Caucasoid, Capoid, Congoid, Australoid and Mongoloid, based on the alleged timing of each group's evolution from Homo erectus. Positing the Capoid race as a separate racial entity, and labeling the two major divisions of what he called the Congoid race as being the "African Negroes" and the "Pygmies", he divided indigenous Africans into distinct Congoid and Capoid groups.[26][27] Coon wrote:

The fourth [racial group] comprises the Negroes and Pygmies of Africa. I have named it Congoid after the region (not a specific nation) which contains both kinds of people. The term Negroid has been deliberately omitted to avoid confusion. It has been applied both to Africans and the spiral-haired peoples of Southern Asia and Oceania who are not genetically related to each other, as far as we know.[28]

Afrocentrist author Cheikh Anta Diop contrasted "Negroid" with "Cro-Magnoid" in his publications arguing for "Negroid" primacy. Grimaldi Man, Upper Paleolithic fossils found in Italy in 1901, had been classified as Negroid by Boule and Vallois (1921). The identification was obsolete by the 1960s, but was controversially revived by Diop (1989).[29]

In the context of the first peopling of the Sahara, there was a debate in the 1970s whether the non-negroid, mixed, or negroid fossils found in the region were older.[30] Asselar man, a 6,400 year old fossil discovered in 1927 in the Adrar des Ifoghas near Essouk (now the Kidal Region of Mali), was claimed as the oldest known anatomically modern human skeleton of Negroid type.[31]

Subraces

In the first half of the 20th century, the traditional subraces of the Negroid race were regarded as being the True Negro, the Forest Negro, the Bantu Negro, the Nilote, the Negrillo (also known as the African Pygmy), the Khoisan (often historically referred to as Hottentot and Bushman), the Negrito (also known as the Asiatic Pygmy), and the Oceanic Negroids (consisting of the Papuan and Melanesian).[32]

By the 1960s, some scholars regarded the Khoisan as a separate race known as the Capoid race, while others continued to regard them as a Negroid subrace.[33] The term "Congoid" was frequently used interchangeably with "Negroid", with the main difference being that Congoid excluded the Capoid taxon.[34]

Physical features

Craniofacial traits

In modern craniofacial anthropometry, Negroid describes features that typify skulls of black people. These include a broad and round nasal cavity; no dam or nasal sill; Quonset hut-shaped nasal bones; notable facial projection in the jaw and mouth area (prognathism); a rectangular-shaped palate; a square or rectangular eye orbit shape;[35] a large interorbital distance; a more undulating supraorbital ridge;[36] and large teeth.[37]

According to George W. Gill and other modern forensic anthropologists, physical traits of Negroid crania are generally distinct from those of the Caucasoid and Mongoloid races. They assert that they can identify a Negroid skull with an accuracy of up to 95%.[38] However, Alan H. Goodman cautions that this precision estimate is often based on methodologies using subsets of samples. He also argues that scientists have a professional and ethical duty to avoid such biological analyses since they could potentially have sociopolitical effects.[39] Although widely used in forensic anthropology, some have also challenged the accuracy of craniofacial anthropometry vis-a-vis different human populations that have developed in close proximity to one another and those of mixed ethnic heritage.[40] Since the distinguishing racial traits are not set until puberty, they are also difficult to ascertain in preadolescent skulls.[36]

Variation in craniofacial form between humans has been found to be largely due to differing patterns of biological inheritance. Modern cross-analysis of osteological variables and genome-wide SNPs has identified specific genes, which control this craniofacial development. Of these genes, DCHS2, RUNX2, GLI3, PAX1 and PAX3 were found to determine nasal morphology, whereas EDAR impacts chin protrusion.[41]

Neoteny

Ashley Montagu lists "neotenous structural traits in which...Negroids [generally] differ from Caucasoids... flattish nose, flat root of the nose, narrower ears, narrower joints, frontal skull eminences, later closure of premaxillary sutures, less hairy, longer eyelashes, [and] cruciform pattern of second and third molars".[42] He also suggested that in the extinct Negroid group termed the "Boskopoids", pedomorphic traits proceeded further than in other Negroids.[42] Additionally, Montagu wrote that the Boskopoids had larger brains than modern humans (1,700 cubic centimeters cranial capacity compared to 1,400 cubic centimeters in modern-day humans), and the projection of their mouth was less than in other Negroids.[42] He believed that the Boskopoids were the ancestors of the Khoisan.[42]

Hair

A.H.Keane (1899) described tightly coiled, kinky hair as an ubiquitous trait among "Negroid" populations. By consequence, he considered the presence of looser, frizzly hair texture in other populations an indication of possible admixture with "Negroid" peoples.[43]

Commenting on the lack of body hair (glabrousness) of Negroids and Mongoloids, Carleton S. Coon wrote that "[b]oth negroid and mongoloid skin conditions are inimical to excessive hair development except upon the scalp".[44]

Skin pigmentation

"Negroid" skin pigmentation was described as varying from very dark brown to light brown.[13] As dark skin is also relatively common in human groups that have historically not been defined as "Negroid", including many populations in both Africa and Asia, it is only when present with other typical Negroid physical traits such as broad facial features, Negroid cranial characteristics, large teeth, prognathism, afro-textured hair and neoteny, that it has been used in Negroid classification.[43] Populations with frequently dark skin yet on the whole lacking the suite of Negroid physical traits were thus usually not regarded as "Negroid", but instead as either "dark Caucasoid" (e.g. Hamitic/Ethiopid and Arabid) or "Australoid" depending on their other salient physical attributes. By contrast, populations with relatively light skin yet generally possessing typical Negroid physical characteristics, such as the Khoisan, were still regarded as "Negroid".[43]

Athleticism

In the context of prominent successes of African-American athletes like Jesse Owens during the 1936 Summer Olympics, the speed advantage of the "Negroid type of calf, foot and heel bone" was discussed. But anthropologist W. Montague Cobb pointed out that "there is not a single physical characteristic, including skin color, which all the Negro stars have in common which definitely classify them as Negroes."[45]

Criticism

| Black people |

|---|

| African diaspora |

|

| Asia-Pacific |

|

| African-derived culture |

| History |

| Race-related |

|

| Related topics |

The term "Negroid" is still used in forensic anthropology.[4] In a medical context, some scholars have recommended that the term Negroid be avoided in scientific writings because of its association with scientific racism.[46] This mirrors the decline in usage of the term negro in English, which fell out of favor following the campaigns of the Civil Rights Movement, but was later re-introduced in the US Census of 2010 because it was found that members of the older generation of African Americans continued to identify with it.[47] The Oxford Dictionaries website as of 2018 indicates that "the term Negroid belongs to a set of terms introduced by 19th-century anthropologists attempting to categorize human races(....) such terms are associated with outdated notions of racial types, and so are now potentially offensive and best avoided".[48]

C.S. Coon's evolutionary approach was criticized on the basis that such sorting criteria generally do not produce meaningful results, and that evolutionary divergence was extremely improbable over the given time-frames.[49] Monatagu (1963) argued that Coon's theory on the speciation of Congoids and other Homo sapiens was unlikely because the transmutation of one species to another was a markedly gradual process.[50]

Criticism based on modern genetics

In his 2016 essay Evolution and Notions of Human Race, Alan R. Templeton discusses various criteria used in biology to define subspecies or races. His examples for traits traditionally considered to be racial include skin colour: "[T]he native peoples with the darkest skins live in tropical Africa and Melanesia." While those two groups would traditionally be classified as "black", in reality Africans are more closely related to Europeans than to Melanesians.[51]:359 Another example is malarial resistance, which is often found in African populations, but also in "many European and Asian populations".[51]:359

Templeton concludes: "[T]he answer to the question whether races exist in humans is clear and unambiguous: no."[51]:360

See also

- Demographics of Africa

- Ethnic groups of Africa

References

- Coon, Carleton S. (Carleton Stevens), 1904-1981. (1966). The living races of man. Cape. OCLC 2179809.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Molnar, Stephen (2006). Human Variation: Races, Types, and Ethnic Groups. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-13-192765-0.

- Molnar, Stephen (2006). Human Variation: Races, Types, and Ethnic Groups. Pearson Prentice Hall. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-13-192765-0.

- Fish, Jacqueline T. (2010). Crime Scene Investigation. Elsevier. p. 395. ISBN 978-1-4224-6331-4.

- "A very prominent racial dividing line between African Caucasian and Negroid groups runs west to east, south of the Sahara Desert into Sudan before curving southward toward the Kenyan-Somali border." Stephen Emerson, Hussein Solomon, African security in the twenty-first century: Challenges and opportunities, Oxford University Press (2018), p. 41.

-

- Baum 2006, pp. 84–85: "Finally, Christoph Meiners (1747–1810), the University of Göttingen “popular philosopher” and historian, first gave the term Caucasian racial meaning in his Grundriss der Geschichte der Menschheit (Outline of the History of Humanity, 1785)… Meiners pursued this “Göttingen program” of inquiry in extensive historical-anthropological writings, which included two editions of his Outline of the History of Humanity and numerous articles in Göttingisches Historisches Magazin"

- William R. Woodward (9 June 2015). Hermann Lotze: An Intellectual Biography. Cambridge University Press. p. 260. ISBN 978-1-316-29785-8.

...the five human races identified by Johann Friedrich Blumenbach – Negroes, American Indians, Malaysians, Mongolians, and Caucasians. He chose to rely on Blumenbach, leader of the Göttingen school of comparative anatomy

; also at - Nicolaas A. Rupke (2002). Göttingen and the Development of the Natural Sciences. Wallstein-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-89244-611-8.

For it was at Gottingen in this period that the outlines of a system of classification were laid down in a manner that still shapes the way in which we attempt to comprehend the different varieties of humankind — including usage of such terms as "Caucasian".

- Charles Simon-Aaron (2008). The Atlantic Slave Trade: Empire, Enlightenment, and the Cult of the Unthinking Negro. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-7734-5197-1.

Here, Blumenbach placed the white European at the apex of the human family; he even gave the European a new name — i.e., Caucasian. This relationship also inspired the academic labors of Karl Otfried Muller, C. Meiners and K.A. Heumann, the more important thinkers at Gottingen for our project. (This list is not intended to be exhaustive).

- RACAR, Revue D'art Canadienne: Canadian Art Review. Society for the Promotion of Art History Publications in Canada. 2004.

It is in the context of the shift to the human as both subject and object that Foucault has placed the "invention" of the human sciences, and it is also in this context that the various human histories as conceived and taught at Gottingen — from the theories of race proposed by Christoph Meiners and Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (who would coin the word "Caucasian" in the 1790s) to new theories of history as interpreted by Johann Christoph Gatterer and August Ludwig von Schlozer to a new art history as conceived by Fiorillo — can be considered.

- Pickering, Robert (2009). The Use of Forensic Anthropology. CRC Press. p. 82. ISBN 978-1-4200-6877-1.

- Susanne Berthier-Foglar, Sheila Collingwood-Whittick, Sandrine Tolazzi (2012). Biomapping Indigenous Peoples: Towards an Understanding of the Issues. Rodopi. p. 186. ISBN 978-9401208666. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

The [American Anthropological Association] statement is representative of the prevailing view in the contemporary social sciences. Many social scientists have questioned the assumption that race is a scientific or objective reality, contending that it is forged from the discourses of politics, society, and history.

CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link) - Roberts, C. A. (2013). Studies in Crime: An Introduction to Forensic Archaeology. Routledge. p. 116. ISBN 978-1-135-86287-9.

The concept of biological race has different meanings to many people and often becomes confused with social, political and religious concepts of race. Biological race is the result of an adaptive response to success (Gill, 1986, p. 143) with resulting physical variation. Race can be described in terms of appearance (phenotype) and genetics or units of inheritance (genotype). The biological anthropologist examines skeletal remains to assess human racial variation assigning individuals to three main races, Caucasoid, Negroid and Mongoloid

- Company, Houghton Mifflin (2005). The American Heritage guide to contemporary usage and style. Houghton Mifflin Company. p. 512. ISBN 978-0-618-60499-9.

- "Oid | Define Oid at Dictionary.com". Dictionary.reference.com. Retrieved 2012-06-12.

- Harper, Douglas (November 2001). "Online Etymological Dictionary". Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- Taylor, Karen T. (2010). Forensic Art and Illustration. CRC Press. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-4200-3695-4.

- Bhopal R (December 2007). "The beautiful skull and Blumenbach's errors: the birth of the scientific concept of race". BMJ. 335 (7633): 1308–9. doi:10.1136/bmj.39413.463958.80. PMC 2151154. PMID 18156242.

Blumenbach’s name has been associated with scientific racism, but his arguments actually undermined racism. Blumenbach could not have foreseen the coming abuse of his ideas and classification in the 19th and (first half of the) 20th centuries.

- Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1797). Handbuch der Naturgeschichte. p. 60. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

Es giebt nur eine Gattung (species) im Menschengeschlecht; und alle uns bekannte Völker aller Zeiten und aller Himmelsstriche können von einer gemeinschaftlichen Stammrasse abstammen.

- German: "sehr willkürlich": Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1797). Handbuch der Naturgeschichte. p. 61. Retrieved 2020-05-24.

Alle diese Verschiedenheiten fließen aber durch so mancherley Abstufungen und Uebergänge so unvermerkt zusammen, daß sich keine andre, als sehr willkürliche Grenzen zwischen ihnen festsetzen lassen.

- German: "Aethiopische Rasse": Johann Friedrich Blumenbach (1797). Handbuch der Naturgeschichte. p. 62. Retrieved 2020-06-06.

Die Aethiopische Rasse: Abbild. n. h. Gegenst. tab. 5. mehr oder weniger schwarz; mit schwarzem krausem Haar; vorwärts prominirenden Kiefern, wulstigen Lippen, und stumpfer Nase. Dahin die übrigen Afrikaner, nahmentlich die Neger, die sich dann in die Habessinier, Mauren ꝛc. verlieren, so wie jede andre Menschen-Varietät mit ihren benachbarten Völkerschaften gleichsam zusammen fließt.

- Sanders, Edith R. (October 1969). "The Hamitic Hypothesis; Its Origin and Functions in Time Perspective". The Journal of African History. 10 (4): 521–532. doi:10.1017/S0021853700009683. ISSN 1469-5138. JSTOR 179896.

- Robinson, Michael F. (2016). The Lost White Tribe: Explorers, Scientists, and the Theory that Changed a Continent. Oxford University Press. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-0199978502. Retrieved 19 February 2017.

- Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning. The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, New York: Nation Books 2016. ISBN 978-1-5685-8464-5, chapters 4, 7-12, 14, 16 passim.

- Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning. The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, New York: Nation Books 2016. ISBN 978-1-5685-8464-5, chapter 14.

- Michael, John S. “A New Look at Morton's Craniological Research.” Current Anthropology, vol. 29, no. 2, 1988, pp. 349–354. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/2743412. Accessed 15 June 2020.

- Stephen Jay Gould. The Mismeasure of Man. ISBN 978-0393314250. Retrieved 2020-06-11. and by: Emily S. Renschler and Janet Monge. "The Samuel George Morton Cranial Collection. Historical Significance and New Research". Retrieved 2020-06-11.

- Mismeasure for mismeasure. Nature 474, 419 (2011). doi:10.1038/474419a

- Huxley, T. H. On the Geographical Distribution of the Chief Modifications of Mankind (1870) Journal of the Ethnological Society of London.

- Jackson Jr., John (June 2001). ""In Ways Unacademical": The Reception of Carleton S. Coon's The Origin of Races". Journal of the History of Biology. 34 (2): 247–285. doi:10.1023/A:1010366015968.

- Keita, S.O.Y.; Rick A. Kittles (September 1987). "The Persistence of Racial Thinking and the Myth of Racial Divergence". American Anthropologist. 99 (3): 534–544. doi:10.1525/aa.1997.99.3.534.

- The Origin of Races by Carleton S. Coon, 1962, pages 3-4.

- Masset, C. (1989): Grimaldi : une imposture honnête et toujours jeune, Bulletin de la Société préhistorique française, vol. 86, n° 8, pp. 228–243. "Cornevin seems to ignore the depth of morphological differences that exist between the Black and the White when he dates these differences back to Antiquity as recent as the eleventh millennium B.C. By doing so he opposes the one hypothesis at the disposal of scholars to confer upon the Whites an antiquity equal to that of the Blacks. He errs most regrettably in claiming that the Asselar man looks more like the Cro-Magnoid European of Grimladi and the Bushman than like modern Blacks. By definition, the Grimaldi Negorid is not Cro-Magnoid, and he is the only one the Asselar man could possibly resemble; he shares no feature with the so-called Cro-Magnon man who lived later in the same cave and is the prototype of the White race as the 'Negroid' is the prototype of the Black race." C. A. Diop, The African Origin of Civilization: Myth Or Reality (1989), p. 266.

- J. D. Fage, John Desmond Clark, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge History of Africa vol. 2, Cambridge University Press (1975) p. 336.

- Bassey W. Andah; Alex Ikechukwu Okpoko (2009). Foundations of Civilization in Tropical Africa. Concept Publications. p. 107. ISBN 978-9788406037. Retrieved 15 June 2016.

- Ashley, Montagu (1951). An Introduction to Physical Anthropology – Second Edition (PDF). Charles C. Thomas Publisher. pp. 302–312.

- Jenkins (M.D.), Trefor (1988). The Peoples of Southern Africa: Studies in Diversity and Disease. Witwatersrand University Press for the Institute for the Study of Man in Africa. p. 6.

- Pearson, Roger (1985). Anthropological glossary. R.E. Krieger Pub. Co. p. 38.

- George W. Gill, Stanley Rhine (eds.) (1990). Skeletal Attribution of Race: Methods for Forensic Anthropology. Maxwell Museum of Anthropology. ISBN 978-0-912535-06-7. OCLC 671604288.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Wilkinson, Caroline (2004). Forensic Facial Reconstruction. Cambridge University Press. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-0-521-82003-5. Retrieved 2 June 2015.

- Brace CL, Tracer DP, Yaroch LA, Robb J, Brandt K, Nelson AR, Clines and clusters versus "race:" a test in ancient Egypt and the case of a death on the Nile, (1993), Yrbk Phys Anthropol 36:1–31, p.18

- Gill, George W. 1998. "Craniofacial Criteria in the Skeletal Attribution of Race. " In Forensic Osteology: Advances in the Identification of Human Remains. (2nd edition) Reichs, Kathleen l(ed.), pp. 293–315.

- Diana Smay, George Armelagos (2000). "Galileo wept: A critical assessment of the use of race of forensic anthropolopy" (PDF). Transforming Anthropology. 9 (2): 22–24. doi:10.1525/tran.2000.9.2.19. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- L’engle Williams, Frank; Robert L. Belcher; George J. Armelagos (April 2005). "Forensic Misclassification of Ancient Nubian Crania: Implications for Assumptions about Human Variation" (PDF). Current Anthropology. 46 (2): 340–346. doi:10.1086/428792. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-03. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- Adhikari, K., Fuentes-Guajardo, M., Quinto-Sánchez, M., Mendoza-Revilla, J., Chacón-Duque, J. C., Acuña-Alonzo, V., Gómez-Valdés, J. (2016). "A genome-wide association scan implicates DCHS2, RUNX2, GLI3, PAX1 and EDAR in human facial variation". Nature Communications. 7: 11616. doi:10.1038/ncomms11616. PMC 4874031. PMID 27193062.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Montagu, Ashley Growing Young Published by Greenwood Publishing Group, 1988 ISBN 0-89789-166-X

- Keane, A.H. (1899). Man, Past and Present (PDF).

- Coon, C.S. (1939). The Races of Europe. USA: The Macmillan Company.

- Cited in: Ibram X. Kendi, Stamped from the Beginning. The Definitive History of Racist Ideas in America, New York: Nation Books 2016. ISBN 978-1-5685-8464-5, chapter 27.

- Agyemang, Charles; Raj Bhopal; Marc Bruijnzeels (2005). "Negro, Black, Black African, African Caribbean, African American or what? Labelling African origin populations in the health arena in the 21st century". Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health. 59 (12): 1014–1018. doi:10.1136/jech.2005.035964. PMC 1732973. PMID 16286485. Retrieved 2007-11-06.

- "Census Bureau defends 'negro' addition". UPI. 2010-01-06. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- "Ask Oxford – Definition of Negroid". Oxford Dictionary of English. 2018. Retrieved 2018-05-10.

- Carlson, David; Armelagos, George (September 1971). "Problems in Racial Geography". Annals of the Association of American Geographers. 61 (3): 630–633. doi:10.1111/j.1467-8306.1971.tb00812.x.

- Dobzhansky, Theodosius; Ashley Montagu; C. S. Coon (1963). "Two Views of Coon's "Origin of Races" with Comments by Coon and Replies". Current Anthropology. 4 (4): 360–367. doi:10.1086/200401.

- Templeton, A. (2016). EVOLUTION AND NOTIONS OF HUMAN RACE. In Losos J. & Lenski R. (Eds.), How Evolution Shapes Our Lives: Essays on Biology and Society (pp. 346-361). Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv7h0s6j.26. That this view reflects the consenus among American anthropologists is stated in: Wagner, Jennifer K.; Yu, Joon-Ho; Ifekwunigwe, Jayne O.; Harrell, Tanya M.; Bamshad, Michael J.; Royal, Charmaine D. (February 2017). "Anthropologists' views on race, ancestry, and genetics". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 162 (2): 318–327. doi:10.1002/ajpa.23120. PMC 5299519. PMID 27874171. See also: American Association of Physical Anthropologists (27 March 2019). "AAPA Statement on Race and Racism". American Association of Physical Anthropologists. Retrieved 19 June 2020.