Arab slave trade

The Arab slave trade is the intersection of slavery and trade surrounding the Arab world and Indian Ocean, mainly in Western and Central Asia, Northern and Eastern Africa, India, and Europe.[1][2] This barter occurred chiefly between the medieval era and the early 20th century. The trade was conducted through slave markets in these areas, with the slaves captured mostly from Africa's interior,[3] Southern and Eastern Europe,[4][5][6] the Caucasus, and Central Asia. There is some contention among scholars over whether it is appropriate to call this slave trade as the "Arab slave trade" or "Islamic slave trade." Historians that are against both nomenclature argue that the names imply that slavery and slave trading within these societies were an intrinsic part of Arab culture or Islam when, in reality, the patterns of slaving had more to do with economics.[7] They tend to prefer to name it after a general region or some geographic area in which the slave trading was happening such as the "Trans-Saharan slave trade" or the "Indian Ocean slave trade."

Scope of the trade

African Zanj slaves

The Arab slave trade, across the Sahara desert and across the Indian Ocean, began after Muslim Arab and Swahili traders won control of the Swahili Coast and sea routes during the 9th century (see Sultanate of Zanzibar). These traders captured Bantu peoples (Zanj) from the interior in present-day Kenya, Mozambique and Tanzania and brought them to the coast.[3][8] There, the slaves gradually assimilated in the rural areas, particularly on the Unguja and Pemba islands.[9]

Author N'Diaye estimates that as many as 17 million people were sold into slavery on the coast of the Indian Ocean, the Middle East, and North Africa, and approximately 5 million African slaves were transported by Muslim slave traders via Red Sea, Indian Ocean, and Sahara desert to other parts of the world between 1500 and 1900.[10] Historian Lodhi challenged N'Diaye's figure saying "17 million? How is that possible if the total population of Africa at that time might not even have been 40 million? These statistics did not exist back then."[11] However, French historian Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau also quotes the figure of 17 million as the total number of people transported from the 7th century until 1920, mentionning it amounts to an average of 6,000 people per year.[12][13]

The captives were sold throughout the Middle East. This trade accelerated as superior ships led to more trade and greater demand for labour on plantations in the region. Eventually, tens of thousands of captives were being taken every year.[9][14][15]

The Indian Ocean slave trade was multi-directional and changed over time. To meet the demand for menial labor, Bantu slaves bought by Arab slave traders from southeastern Africa were sold in cumulatively large numbers over the centuries to customers in Egypt, Arabia, the Persian Gulf, India, European colonies in the Far East, the Indian Ocean islands, Ethiopia and Somalia.[1]

Slave labor in East Africa was drawn from the Zanj, Bantu peoples that lived along the East African coast.[8][16] The Zanj were for centuries shipped as slaves by Arab traders to all the countries bordering the Indian Ocean. The Umayyad and Abbasid caliphs recruited many Zanj slaves as soldiers and, as early as 696, there were revolts of Zanj slave soldiers in Iraq.[17] A 7th-century Chinese text mentions ambassadors from Java presenting the Chinese emperor with two Seng Chi (Zanj) slaves as gifts in 614, and 8th- and 9th-century chronicles mention Seng Chi slaves reaching China from the Hindu kingdom of Sri Vijaya in Java.[17]

The Zanj Rebellion, a series of uprisings that took place between 869 and 883 AD near the city of Basra (also known as Basara), situated in present-day Iraq, is believed to have involved enslaved Zanj that had originally been captured from the African Great Lakes region and areas further south in East Africa.[18] It grew to involve over 500,000 slaves and free men who were imported from across the Muslim empire and claimed over "tens of thousands of lives in lower Iraq".[19] The Zanj who were taken as slaves to the Middle East were often used in strenuous agricultural work.[20] As the plantation economy boomed and the Arabs became richer, agriculture and other manual labor work was thought to be demeaning. The resulting labor shortage led to an increased slave market.

It is certain that large numbers of slaves were exported from eastern Africa; the best evidence for this is the magnitude of the Zanj revolt in Iraq in the 9th century, though not all of the slaves involved were Zanj. There is little evidence of what part of eastern Africa the Zanj came from, for the name is here evidently used in its general sense, rather than to designate the particular stretch of the coast, from about 3°N. to 5°S., to which the name was also applied.[21]

The Zanj were needed to take care of:

the Tigris-Euphrates delta, which had become abandoned marshland as a result of peasant migration and repeated flooding, could be reclaimed through intensive labor. Wealthy proprietors "had received extensive grants of tidal land on the condition that they would make it arable." Sugar cane was prominent among the products of their plantations, particularly in Khūzestān Province. Zanj also worked the salt mines of Mesopotamia, especially around Basra.[22]

Their jobs were to clear away the nitrous topsoil that made the land arable. The working conditions were also considered to be extremely harsh and miserable. Many other people were imported into the region, besides Zanj.[23]

Historian M. A. Shaban has argued that rebellion was not a slave revolt, but a revolt of blacks (zanj). In his opinion, although a few runaway slaves did join the revolt, the majority of the participants were Arabs and free Zanj. If the revolt had been led by slaves, they would have lacked the necessary resources to combat the Abbasid government for as long as they did.[24]

Ibn Battuta who visited the ancient African kingdom of Mali in the mid-14th century recounts that the local inhabitants vie with each other in the number of slaves and servants they have, and was himself given a slave boy as a "hospitality gift."[25]

European slaves

During the Middle Ages, the main regions from where slaves were transported to Muslim lands were Central Europe asides from Central Asia and Bilad as-Sudan. Slaves of Northwestern Europe were also favoured. This slave trade was controlled mostly by Western slave traders. The slaves captured by Christians were sent to Muslim lands like Spain and Egypt through France and Venice. Prague served as a major centre for castration of Slavic captives.[26][27] Emirate of Bari also served as an important port for trade of such slaves.[28] After the Byzantine Empire and Venice blocked Arab merchants from European ports, they started importing in slaves from Caucasus and Caspian Sea.[29] In addition slaving raids by Barbary Pirates on the coasts of Western Europe as far as Iceland became a source until suppressed in the early 19th century.

Arab slaves

Arabs were sometimes made into slaves in the Muslim world.[30][31] Sometimes castration was done on Arab slaves. In Mecca, Arab women were sold as slaves according to Ibn Butlan, and certain rulers in West Africa had slave girls of Arab origin.[32][33] According to al-Maqrizi, slave girls with lighter skin were sold to West Africans on hajj.[34][35][36] Ibn Battuta met an Arab slave girl near Timbuktu in Mali in 1353. Battuta wrote that the slave girl was fluent in Arabic, from Damascus, and her master's name was Farbá Sulaymán.[37][38][39] Besides his Damascus slave girl and a secretary fluent in Arabic, Arabic was also understood by Farbá himself.[40]

Islamic and Oriental aspect

Patrick Manning writes that although the "Oriental" or "Arab" slave trade is sometimes called the "Islamic" slave trade, a religious imperative was not the driver of the slavery. He further argues such use of the terms "Islamic trade" or "Islamic world" erroneously treats Africa as being outside Islam, or a negligible portion of the Islamic world.[41] According to European historians, propagators of Islam in Africa often revealed a cautious attitude towards proselytizing because of its effect in reducing the potential reservoir of slaves.[42]

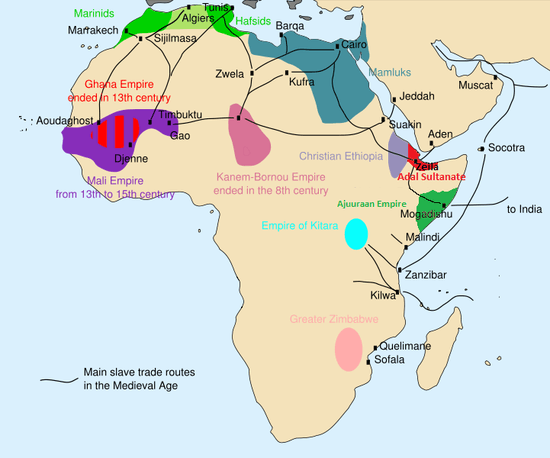

The subject merges with the Oriental slave trade, which followed two main routes in the Middle Ages:

- Overland routes across the Maghreb and Mashriq deserts (Trans-Saharan route)[43]

- Sea routes to the east of Africa through the Red Sea and Indian Ocean (Oriental route)[44][45]

The Arab slave trade originated before Islam and lasted more than a millennium.[46][47][48] To meet the demand for plantation labor, these captured Zanj slaves were shipped to the Arabian peninsula and the Near East, among other areas.[49]

History of the Arab slave trade

— Saladin's secretary Imad al-Din gleefully recounts the capture, enslavement of Christian women by Muslims after the Siege of Jerusalem[50]

From the 7th century until around the 1960s, the Arab slave trade continued in one form or another. Historical accounts and references to slave-owning nobility in Arabia, Yemen and elsewhere are frequent into the early 1920s.[51]

In 641 during the Baqt, a treaty between the Nubian Christian state of Makuria and the new Muslim rulers of Egypt, the Nubians agreed to give Arab traders more privileges of trade in addition to a share in their slave trading.[52]

In Somalia, the Bantu minorities are descended from Bantu groups that had settled in Southeast Africa after the initial expansion from Nigeria/Cameroon. To meet the demand for menial labor, Bantus from southeastern Africa captured by Somali slave traders were sold in cumulatively large numbers over the centuries to customers in Somalia and other areas in Northeast Africa and Asia.[1] People captured locally during wars and raids were also sometimes enslaved by Somalis mostly of Oromo and Nilotic origin.[53] [54][55] However, the perception, capture, treatment and duties of both groups of slaves differed markedly.[55] [56] From 1800 to 1890, between 25,000–50,000 Bantu slaves are thought to have been sold from the slave market of Zanzibar to the Somali coast.[57] Most of the slaves were from the Majindo, Makua, Nyasa, Yao, Zalama, Zaramo and Zigua ethnic groups of Tanzania, Mozambique and Malawi. Collectively, these Bantu groups are known as Mushunguli, which is a term taken from Mzigula, the Zigua tribe's word for "people" (the word holds multiple implied meanings including "worker", "foreigner", and "slave").[58]

During the second half of the 19th century and early 20th century, slaves shipped from Ethiopia had a high demand in the markets of the Arabian peninsula and elsewhere in the Middle East. They were mostly domestic servants, though some served as agricultural labourers, or as water carriers, herdsmen, seamen, camel drivers, porters, washerwomen, masons, shop assistants and cooks. The most fortunate of the men worked as the officials or bodyguards of the ruler and emirs, or as business managers for rich merchants.[59] They enjoyed significant personal freedom and occasionally held slaves of their own. Besides European, Caucasian, Javanese and Chinese girls brought in from the Far East, "red" (non-black) Ethiopian young females were among the most valued concubines. The most beautiful ones often enjoyed a wealthy lifestyle, and became mistresses of the elite or even mothers to rulers.[59] The principal sources of these slaves, all of whom passed through Matamma, Massawa and Tadjoura on the Red Sea, were the southwestern parts of Ethiopia, in the Oromo and Sidama country.[60]

In the Central African Republic, during the 16th and 17th centuries Muslim slave traders began to raid the region as part of the expansion of the Saharan and Nile River slave routes. Their captives were enslaved and shipped to the Mediterranean coast, Europe, Arabia, the Western Hemisphere, or to the slave ports and factories along the West and North Africa coasts or South along the Ubanqui and Congo rivers.[61][62]

The Arab slave trade in the Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Mediterranean Sea long predated the arrival of any significant number of Europeans on the African continent south of the Sahara.[51][63]

While in Wadi Safra during WWI, T.E. Lawrence wrote, "...these blacks were originally from Africa, brought over as children by their nominal Takruri fathers, and sold during the pilgrimage, in Mecca. Some became house or body servants with their masters; but the majority were sent out to the palm villages...and did all the manual work of the holding."[64]

Some descendants of African slaves brought to the Middle East during the slave-trade still live there today, and are aware of their African origins.[65][66]

European colonialism

Historian and Black Power activist Walter Rodney has criticised the "Arab Slave Trade" label as a misnomer, as it obscures the extent to which it was also a European slave trade. He argues that by the 18th and 19th centuries, the East African slave trade network came to be dominated by European colonialists. Most East African slaves during the 18th and 19th centuries ended up in European-owned plantation economies around the Indian Ocean region, such as Mauritius, Réunion, Seychelles, and the Cape of Good Hope, in addition to many taken to the Americas. The East African slave trade reached its peak during this period, as a result of the European capitalist plantation slavery system. This in turn increased demand for slave-grown products in some Arab countries which adopted the European capitalist plantation slavery system, such as Zanzibar.[2]

19th century

In the 1800s, the slave trade from Africa to the Islamic countries picked up significantly when the European slave trade dropped around the 1850s only to be ended with European colonisation of Africa around 1900.[67]

In 1814, Swiss explorer Johann Burckhardt wrote of his travels in Egypt and Nubia, where he saw the practice of slave trading: "I frequently witnessed scenes of the most shameless indecency, which the traders, who were the principal actors, only laughed at. I may venture to state, that very few female slaves who have passed their tenth year, reach Egypt or Arabia in a state of virginity."[68]

Richard Francis Burton wrote about the Medina slaves, during his 1853 Haj, "a little black boy, perfect in all his points, and tolerably intelligent, costs about a thousand piastres; girls are dearer, and eunuchs fetch double that sum." In Zanzibar, Burton found slaves owning slaves.[69]

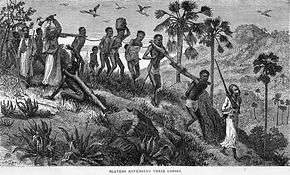

David Livingstone wrote of the slave trade in the African Great Lakes region, which he visited in the mid-nineteenth century:

To overdraw its evils is a simple impossibility ...

19th June 1866 - We passed a woman tied by the neck to a tree and dead, the people of the country explained that she had been unable to keep up with the other slaves in a gang, and her master had determined that she should not become anyone's property if she recovered.

26th June. - ...We passed a slave woman shot or stabbed through the body and lying on the path: a group of men stood about a hundred yards off on one side, and another of the women on the other side, looking on; they said an Arab who passed early that morning had done it in anger at losing the price he had given for her, because she was unable to walk any longer.

27th June 1866 - To-day we came upon a man dead from starvation, as he was very thin. One of our men wandered and found many slaves with slave-sticks on, abandoned by their masters from want of food; they were too weak to be able to speak or say where they had come from; some were quite young.[70]

The strangest disease I have seen in this country seems really to be broken-heartedness, and it attacks free men who have been captured and made slaves... Twenty one were unchained, as now safe; however all ran away at once; but eight with many others still in chains, died in three days after the crossing. They described their only pain in the heart, and placed the hand correctly on the spot, though many think the organ stands high up in the breast-bone.[73]

Zanzibar was once East Africa's main slave-trading port, and under Omani Arabs in the 19th century as many as 50,000 slaves were passing through the city each year.[74]

Livingstone wrote in a letter to the editor of the New York Herald:

And if my disclosures regarding the terrible Ujijian slavery should lead to the suppression of the East Coast slave trade, I shall regard that as a greater matter by far than the discovery of all the Nile sources together.[75]

20th century

During the Second Sudanese Civil War (1983-2005) people were taken into slavery; estimates of abductions range from 14,000 to 200,000.[76]

Slavery in Mauritania was legally abolished by laws passed in 1905, 1961, and 1981.[77] It was finally criminalized in August 2007.[78] It is estimated that up to 600,000 Mauritanians, or 20% of Mauritania's population, are currently in conditions which some consider to be "slavery", namely, many of them used as bonded labour due to poverty.[79]

Slavery was comparatively recently outlawed in Oman (1970),[80] Qatar (1952), Saudi Arabia, and Yemen (both in 1962).[81]

Historical and geographical context

Islamic world

Islamic sharia law allowed slavery but prohibited slavery involving other free men, allowing only the enslavement of prisoners of war;[82] as a result, the main target for slavery were the people who lived in the frontier areas of the Muslim world. Slaves initially came from various regions, including Central Asia (such as mamluks) and Europe (such as saqaliba), but by the modern period, slaves came mostly from Africa.[83]

According to the sharia law, slaves were allowed to earn their living if they opted for that, otherwise it is the owner's (master) duty to provide for that. They also could not be forced to earn money for their masters unless with an agreement between the slave and the master.[84]

This concept is called مخارجة (mukhārajah) (Lane: "And خَارَجَهُ He made an agreement with him, namely, his slave that he (the latter) should pay him a certain impost at the expiration of every month; the slave being left at liberty to work: in which case the slave is termed عَبْدٌ مُخَارِجٌ") in Islamic law. If slaves agree to that and they would like the money they earn to be counted toward their emancipation, then this has to be written in the form of a contract between the slave and the master. This is called مكاتبة (mukātaba) in Islamic jurisprudence which is only, by consensus, a recommendation,[84] and accepting a request for a mukātaba from slaves is thus not obligatory for masters.[85] Although the owner did not have to comply with it, it was considered praiseworthy to do so.[86]

The framework of Islamic civilisation was a well-developed network of towns and oasis trading centers with the market (souq, bazaar) at its heart. These towns were inter-connected by a system of roads crossing semi-arid regions or deserts. The routes were traveled by convoys, and slaves formed part of this caravan traffic.

In contrast to the Atlantic slave trade, where the male-female ratio was 2:1 or 3:1, the Arab slave trade instead usually had a higher female-to-male ratio. This suggests a general preference for female slaves. Concubinage and reproduction served as incentives for importing female slaves (often Caucasian), though many were also imported mainly for performing household tasks.[87]

Arab views on African peoples

Abdelmajid Hannoum, a professor at Wesleyan University, states that racist attitudes were not prevalent until the 18th and 19th century.[88] According to Arnold J. Toynbee: "The extinction of race consciousness as between Muslims is one of the outstanding achievements of Islam and in the contemporary world there is, as it happens, a crying need for the propagation of this Islamic virtue."[89]

In 2010, at the Second Afro-Arab summit Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi apologized for Arab involvement in the African slave trade, saying: "I regret the behavior of the Arabs... They brought African children to North Africa, they made them slaves, they sold them like animals, and they took them as slaves and traded them in a shameful way. I regret and I am ashamed when we remember these practices. I apologize for this."[90]

Africa: 8th through 19th centuries

In April 1998, Elikia M'bokolo, wrote in Le Monde diplomatique. "The African continent was bled of its human resources via all possible routes. Across the Sahara, through the Red Sea, from the Indian Ocean ports and across the Atlantic. At least ten centuries of slavery for the benefit of the Muslim countries (from the ninth to the nineteenth)." He continues: "Four million slaves exported via the Red Sea, another four million through the Swahili ports of the Indian Ocean, perhaps as many as nine million along the trans-Saharan caravan route, and eleven to twenty million (depending on the author) across the Atlantic Ocean"[91]

In the 8th century, Africa was dominated by Arab-Berbers in the north: Islam moved southwards along the Nile and along the desert trails.

- The Sahara was thinly populated. Nevertheless, since antiquity there had been cities living on a trade in salt, gold, slaves, cloth, and on agriculture enabled by irrigation: Tiaret, Oualata, Sijilmasa, Zaouila, and others.

- In the Middle Ages, the general Arabic term bilâd as-sûdân ("Land of the Blacks") was used for the vast Sudan region (an expression denoting West and Central Africa[92]), or sometimes extending from the coast of West Africa to Western Sudan.[93] It provided a pool of manual labour for North and Saharan Africa. This region was dominated by certain states and people: the Ghana Empire, the Empire of Mali, the Kanem-Bornu Empire, the Fulani and Hausa.

- In the Horn of Africa, the coasts of the Red Sea and Indian Ocean were controlled by local Somali and other Muslims, and Yemenis and Omanis had merchant posts along the coasts. The Ethiopian coast, particularly the port of Massawa and Dahlak Archipelago, had long been a hub for the exportation of slaves from the interior by the Kingdom of Aksum and earlier polities. The port and most coastal areas were largely Muslim, and the port itself was home to a number of Arab and Indian merchants.[94] The Solomonic dynasty of Ethiopia often exported Nilotic slaves from their western borderland provinces, or from newly conquered southern provinces.[95] The Somali and Afar Muslim sultanates, such as the Adal Sultanate, also exported Nilotic slaves that they captured from the interior.[96]

- In the African Great Lakes region, Omani and Yemeni traders set up slave-trading posts along the southeastern coast of the Indian Ocean; most notably in the archipelago of Zanzibar, along the coast of present-day Tanzania. The Zanj region or Swahili Coast flanking the Indian Ocean continued to be an important area for the Oriental slave trade up until the 19th century. Livingstone and Stanley were then the first Europeans to penetrate to the interior of the Congo Basin and to discover the scale of slavery there. The Arab Tippu Tip extended his influence there and captured many people as slaves. After Europeans had settled in the Gulf of Guinea, the trans-Saharan slave trade became less important. In Zanzibar, slavery was abolished late, in 1897, under Sultan Hamoud bin Mohammed.

Geography of the slave trade

"Supply" zones

There is historical evidence of North African Muslim slave raids all along the Mediterranean coasts across Christian Europe.[97] The majority of slaves traded across the Mediterranean region were predominantly of European origin from the 7th to 15th centuries.[98]

Slaves were also brought into the Arab world via Central Asia, mainly of Turkic or Tartar origin. Many of these slaves later went on to serve in the armies forming an elite rank.

- Nubia and Ethiopia were also "exporting" regions: in the 15th century, Ethiopians sold slaves from western borderland areas (usually just outside the realm of the Emperor of Ethiopia) or Ennarea,[99] which often ended up in India, where they worked on ships or as soldiers. They eventually rebelled and took power (dynasty of the Habshi Kings).

- The Sudan region and Saharan Africa formed another "export" area, but it is impossible to estimate the scale, since there is a lack of sources with figures.

- Finally, the slave traffic affected eastern Africa, but the distance and local hostility slowed this section of the Oriental trade.

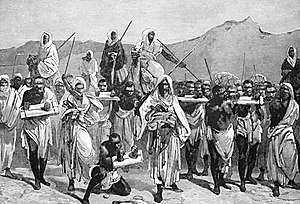

Routes

According to professor Ibrahima Baba Kaké there were four main slavery routes to the Arab world, from east to west of Africa, from the Maghreb to the Sudan, from Tripolitania to central Sudan and from Egypt to the Middle East.[100] Caravan trails, set up in the 9th century, went past the oasis of the Sahara; travel was difficult and uncomfortable for reasons of climate and distance. Since Roman times, long convoys had transported slaves as well as all sorts of products to be used for barter. To protect against attacks from desert nomads, slaves were used as an escort. Any who slowed the progress of the caravan were killed.

Historians know less about the sea routes. From the evidence of illustrated documents, and travellers' tales, it seems that people travelled on dhows or jalbas, Arab ships which were used as transport in the Red Sea. Crossing the Indian Ocean required better organisation and more resources than overland transport. Ships coming from Zanzibar made stops on Socotra or at Aden before heading to the Persian Gulf or to India. Slaves were sold as far away as India, or even China: there was a colony of Arab merchants in Canton. Serge Bilé cites a 12th-century text which tells us that most well-to-do families in Canton had black slaves whom they regarded as savages and demons because of their physical appearance. Although Chinese slave traders bought slaves (Seng Chi i.e. the Zanj[17]) from Arab intermediaries and "stocked up" directly in coastal areas of present-day Somalia, the local Somalis—referred to as Baribah and Barbaroi (Berbers) by medieval Arab and ancient Greek geographers, respectively (see Periplus of the Erythraean Sea),[16][101][102] and no strangers to capturing, owning and trading slaves themselves[103]—were not among them:[104]

One important commodity being transported by the Arab dhows to Somalia was slaves from other parts of East Africa. During the nineteenth century, the East African slave trade grew enormously due to demands by Arabs, Portuguese, and French. Slave traders and raiders moved throughout eastern and central Africa to meet the rising demand for enslaved men, women, and children. The Bantus inhabiting Somalia are descended from Bantu groups that had settled in Southeast Africa after the initial expansion from Nigeria/Cameroon, and whose members were later captured and sold into the Arab slave trade.[56] The Bantus are ethnically, physically, and culturally distinct from Somalis, and they have remained marginalized ever since their arrival in Somalia.[105][106]

Barter

Slaves were often bartered for objects of various kinds: in the Sudan, they were exchanged for cloth, trinkets and so on. In the Maghreb, slaves were swapped for horses. In the desert cities, lengths of cloth, pottery, Venetian glass slave beads, dyestuffs and jewels were used as payment. The trade in black slaves was part of a diverse commercial network. Alongside gold coins, cowrie shells from the Indian Ocean or the Atlantic (Canaries, Luanda) were used as money throughout sub-saharan Africa (merchandise was paid for with sacks of cowries).[107]

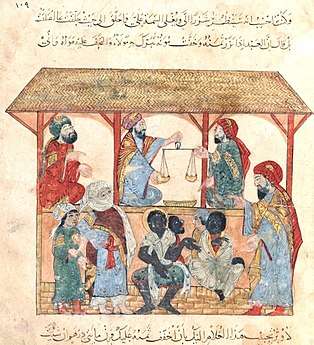

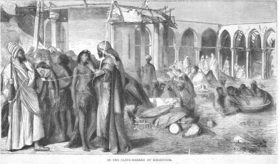

Slave markets and fairs

Enslaved Africans were sold in the towns of the Arab World. In 1416, al-Maqrizi told how pilgrims coming from Takrur (near the Senegal River) brought 1,700 slaves with them to Mecca. In North Africa, the main slave markets were in Morocco, Algiers, Tripoli and Cairo. Sales were held in public places or in souks.

Potential buyers made a careful examination of the "merchandise": they checked the state of health of a person who was often standing naked with wrists bound together. In Cairo, transactions involving eunuchs and concubines happened in private houses. Prices varied according to the slave's quality. Thomas Smee, the commander of the British research ship Ternate, visited such a market in Zanzibar in 1811 and gave a detailed description:

'The show' commences about four o'clock in the afternoon. The slaves, set off to the best advantage by having their skins cleaned and burnished with cocoa-nut oil, their faces painted with red and white stripes and the hands, noses, ears and feet ornamented with a profusion of bracelets of gold and silver and jewels, are ranged in a line, commencing with the youngest, and increasing to the rear according to their size and age. At the head of this file, which is composed of all sexes and ages from 6 to 60, walks the person who owns them; behind and at each side, two or three of his domestic slaves, armed with swords and spears, serve as guard. Thus ordered the procession begins, and passes through the market-place and the principle streets... when any of them strikes a spectator's fancy the line immediately stops, and a process of examination ensues, which, for minuteness, is unequalled in any cattle market in Europe. The intending purchaser having ascertained there is no defect in the faculties of speech, hearing, etc., that there is no disease present, next proceeds to examine the person; the mouth and the teeth are first inspected and afterwards every part of the body in succession, not even excepting the breasts, etc., of the girls, many of whom I have seen handled in the most indecent manner in the public market by their purchasers; indeed there is every reasons to believe that the slave-dealers almost universally force the young girls to submit to their lust previous to their being disposed of. From such scenes one turns away with pity and indignation.[108]

Towns and ports involved in the slave trade

Legacy

The history of the slave trade has given rise to numerous debates amongst historians. For one thing, specialists are undecided on the number of Africans taken from their homes; this is difficult to resolve because of a lack of reliable statistics: there was no census system in medieval Africa. Archival material for the transatlantic trade in the 16th to 18th centuries may seem useful as a source, yet these record books were often falsified. Historians have to use imprecise narrative documents to make estimates which must be treated with caution: Luiz Felipe de Alencastro states that there were 8 million slaves taken from Africa between the 8th and 19th centuries along the Oriental and the Trans-Saharan routes.[109]

Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau has put forward a figure of 17 million African people enslaved (in the same period and from the same area) on the basis of Ralph Austen's work.[110] Ronald Segal estimates between 11.5 and 14 million were enslaved by the Arab slave trade.[111][112][113] Other estimates place it around 11.2 million.[114]

There has also been a considerable genetic impact on Arabs throughout the Arab world from pre-modern African and European slaves.[115]

Primary sources

Medieval Arabic sources

These are given in chronological order. Scholars and geographers from the Arab world had been travelling to Africa since the time of Muhammad in the 7th century.

- Al-Masudi (died 957), Muruj adh-dhahab or The Meadows of Gold, the reference manual for geographers and historians of the Muslim world. The author had travelled widely across the Arab world as well as the Far East.

- Ya'qubi (9th century), Kitab al-Buldan or Book of Countries

- Abraham ben Jacob (Ibrahim ibn Jakub) (10th century), Jewish merchant from Córdoba[116]

- Al-Bakri, author of Kitāb al-Masālik wa'l-Mamālik or Book of Roads and Kingdoms, published in Córdoba around 1068, gives us information about the Berbers and their activities; he collected eyewitness accounts on Saharan caravan routes.

- Muhammad al-Idrisi (died circa 1165), Description of Africa and Spain

- Ibn Battuta (died circa 1377), Moroccan geographer who travelled to sub-Saharan Africa, to Gao and to Timbuktu. His principal work is called A Gift to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling.

- Ibn Khaldun (died in 1406), historian and philosopher from North Africa. Sometimes considered as the historian of Arab, Berber and Persian societies. He is the author of Muqaddimah or Historical Prolegomena and History of the Berbers.

- Al-Maqrizi (died in 1442), Egyptian historian. His main contribution is his description of Cairo markets.

- Leo Africanus (died circa 1548), author of Descrittione dell' Africa or Description of Africa, a rare description of Africa.

- Rifa'a al-Tahtawi (1801–1873), who translated medieval works on geography and history. His work is mostly about Muslim Egypt.

- Joseph Cuoq, Collection of Arabic sources concerning Western Africa between the 8th and 16th centuries (Paris 1975)

European texts (16th–19th centuries)

- João de Castro, Roteiro de Lisboa a Goa (1538)

- James Bruce, (1730–1794), Travels to Discover the Source of the Nile (1790)

- René Caillié, (1799–1838), Journal d'un voyage à Tombouctou

- Robert Adams, The Narrative of Robert Adams (1816)

- Mungo Park, (1771–1806), Travels in the Interior of Africa (1816)

- Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, (1784–1817), Travels in Nubia (1819)

- Heinrich Barth, (1821–1865), Travels and Discoveries in North and Central Africa (1857)

- Richard Francis Burton, (1821–1890), The Lake Regions of Central Africa (1860)

- David Livingstone, (1813–1873), Travel diaries (1866–1873)

- Henry Morton Stanley, (1841–1904), Through the Dark Continent (1878)

Other sources

- Historical manuscripts such as the Tarikh al-Sudan, the Adalite Futuh al-Habash, the Abyssinian Kebra Nagast, and various Arabic and Ajam documents

- African oral tradition

- Kilwa Chronicle (16th century fragments)

- Numismatics: analysis of coins and of their diffusion

- Archaeology: architecture of trading posts and of towns associated with the slave trade

- Iconography: Arab and Persian miniatures in major libraries

- European engravings, contemporary with the slave trade, and some more modern

- Photographs from the 19th century onward

See also

- Abolition of slavery timeline

- Black orientalism

- History of slavery in the Muslim world

- Malê revolt – largest Muslim slave uprising in Brazil

- Mamluk – Muslim soldiers and rulers of slave origin

- Slavery in 21st-century Islamism

- Slavery in antiquity

- Slavery in Iran

- Slavery in modern Africa

- Slavery in the Ottoman Empire

- Transatlantic slave trade

- White slavery

References

- This article was initially translated from the featured French wiki article "Traite musulmane" on 19 May 2006.

- Gwyn Campbell, The Structure of Slavery in Indian Ocean Africa and Asia, 1 edition, (Routledge: 2003), p.ix

- Rodneyʼ, Walter (1972). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications. p. 97. ISBN 9781906387945. Retrieved 29 May 2017.

- Ochiengʼ, William Robert (1975). Eastern Kenya and Its Invaders. East African Literature Bureau. p. 76. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Robert C. Davis (December 2003). Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast and Italy, 1500-1800. London: Palgrave Macmillan. p. 45. ISBN 978-0333719664. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Jeff Grabmeier (8 March 2004). "When Europeans Were Slaves: Research Suggest White Slavery Was Much More Common Than Previously Believed". researchnews.osu.edu. Columbus, Ohio: OSU News Research Archive. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Based on "records for 27,233 voyages that set out to obtain slaves for the Americas". Stephen Behrendt, "Transatlantic Slave Trade", Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience (New York: Basic Civitas Books, 1999), ISBN 0-465-00071-1.

- S. Hopper, Matthew (2015). Slaves of One Master: Globalization and Slavery in Arabia in the Age of Empire. Yale University Press. p. 7.

- Bethwell A. Ogot, Zamani: A Survey of East African History, (East African Publishing House: 1974), p.104

- Lodhi, Abdulaziz (2000). Oriental influences in Swahili: a study in language and culture contacts. Acta Universitatis Gothoburgensis. p. 17. ISBN 978-9173463775.

- "Focus on the slave trade". BBC. 3 September 2001. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017.

- "East Africa's forgotten slave trade". Deutsche Welle. 22 August 2019.

- Lacoste, Yves (2005). "Hérodote a lu : Les Traites négrières, essai d'histoire globale, de Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau" [Book Review: African Slave Trade, an Attempted Global History, by Olivier Pétré-Grenouilleau]. Hérodote (in French) (117): 196–205. doi:10.3917/her.117.0193. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- Pétré-Grenouilleau, Olivier (2004). Les Traites négrières, essai d’histoire globale [African Slave Trade, an Attempted Global History] (in French). Paris: Gallimard. ISBN 9782070734993.

- John Donnelly Fage and William Tordoff (December 2001). A History of Africa (4 ed.). Budapest: Routledge. p. 258. ISBN 9780415252485.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Tannenbaum, Edward R.; Dudley, Guilford (1973). A History of World Civilizations. Wiley. p. 615. ISBN 978-0471844808.

- F.R.C. Bagley et al., The Last Great Muslim Empires, (Brill: 1997), p.174

- Roland Oliver (1975). Africa in the Iron Age: c.500 BC-1400 AD (reprint ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 192. ISBN 9780521099004.

- Rodriguez, Junius P. (2007). Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion, Volume 2. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 585. ISBN 978-0313332739.

- Asquith, Christina. "Revisiting the Zanj and Re-Visioning Revolt: Complexities of the Zanj Conflict – 868-883 Ad – slave revolt in Iraq". Questia.com. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- "Islam, From Arab To Islamic Empire: The Early Abbasid Era". History-world.org. Archived from the original on 2012-10-11. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- Talhami, Ghada Hashem (1 January 1977). "The Zanj Rebellion Reconsidered". The International Journal of African Historical Studies. 10 (3): 443–461. doi:10.2307/216737. JSTOR 216737.

- "the Zanj: Towards a History of the Zanj Slaves' Rebellion". Archived from the original on October 27, 2009. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- "Hidden Iraq". William Cobb.

- Shaban 1976, pp. 101-02.

- Noel King (ed.), Ibn Battuta in Black Africa, Princeton 2005, p. 54

- Charlemagne, Muhammad, and the Arab Roots of Capitalism by Gene W. Heck. Munich: Walter de Gruyter. 2009. p. 316. ISBN 978-3-406-58450-3.

- Atlas of the Year 1000. Munich: Harvard University Press. 2009. p. 72. ISBN 978-3-406-58450-3.

- Packard, Sidney Raymond (1973). 12th century Europe: an interpretive essay. p. 62.

- Pargas, Damian Alan; Roşu, Felicia (2017-12-07). Critical Readings on Global Slavery (4 vols.). pp. 653, 654. ISBN 9789004346611.

- Muhammad A. J. Beg, The "serfs" of Islamic society under the Abbasid regime, Islamic Culture, 49, 2, 1975, p. 108

- Owen Rutter (1986). The pirate wind: tales of the sea-robbers of Malaya. Oxford University Press. p. 140.

- W. G. Clarence-Smith (2006). Islam and the Abolition of Slavery. Oxford University Press. pp. 70–. ISBN 978-0-19-522151-0.

- Humphrey J. Fisher (1 August 2001). Slavery in the History of Muslim Black Africa. NYU Press. pp. 182–. ISBN 978-0-8147-2716-4.

- Chouki El Hamel (27 February 2014). Black Morocco: A History of Slavery, Race, and Islam. Cambridge University Press. pp. 129–. ISBN 978-1-139-62004-8.

- Shirley Guthrie (1 August 2013). Arab Women in the Middle Ages: Private Lives and Public Roles. Saqi. ISBN 978-0-86356-764-3.

- William D. Phillips (1985). Slavery from Roman Times to the Early Transatlantic Trade. Manchester University Press. pp. 126–. ISBN 978-0-7190-1825-1.

- Ibn Batuta; Said Hamdun; Noel Quinton King (March 2005). Ibn Battuta in Black Africa. Markus Wiener Publishers. p. 65. ISBN 978-1-55876-336-4.

- Ibn Battuta (1 September 2004). Travels in Asia and Africa, 1325-1354. Psychology Press. pp. 334–. ISBN 978-0-415-34473-9.

- Raymond Aaron Silverman (1983). History, art and assimilation: the impact of Islam on Akan material culture. University of Washington. p. 51.

- Noel Quinton King (1971). Christian and Muslim in Africa. Harper & Row. p. 22.

- Manning (1990) p.10

- Murray Gordon, Slavery in the Arab World, New Amsterdam Press, New York, 1989. Originally published in French by Editions Robert Laffont, S.A. Paris, 1987, page 28.

- "Battuta's Trip: Journey to West Africa (1351 - 1353)". 2010-06-28. Archived from the original on June 28, 2010. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- Susi O'Neill. "The blood of a nation of Slaves in Stone Town". www.pilotguides.com. Globe Trekker. Archived from the original on December 25, 2008. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- Kevin Mwachiro (30 March 2007). "BBC Remembering East African slave raids". Nairobi: BBC. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- "Know about Islamic Slavery in Africa" Archived October 31, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- "The Forgotten Holocaust: The Eastern Slave Trade". Archived from the original on 2009-10-26.

- Irfan Shahid, Byzantium and the Arabs in the Sixth Century, Dumbarton Oaks, 2002, p. 364 documents; Ghassanid Arabs seizing and selling 20,000 Samaritans as slaves in the year 529, before the rise of Islam.

- Proceedings of the Seminar for Arabian Studies, Volumes 21-22. 1991. p. 87. Retrieved 17 January 2015.

- Everyone's History: A Reader-Friendly World History of War, Bravery, Slavery, Religion, Autocracy, Democracy, and Science, 1 AD to 2000 AD, p. 179.

- Mintz, S. Digital History Slavery, Facts & Myths

- Jay Spaulding. "Medieval Christian Nubia and the Islamic World: A Reconsideration of the Baqt Treaty," International Journal of African Historical Studies XXVIII, 3 (1995)

- Meinhof, Carl (1979). Afrika und Übersee: Sprachen, Kulturen, Volumes 62-63. D. Reimer. p. 272.

- Bridget Anderson, World Directory of Minorities, (Minority Rights Group International: 1997), p. 456.

- Catherine Lowe Besteman, Unraveling Somalia: Race, Class, and the Legacy of Slavery, (University of Pennsylvania Press: 1999), p. 116.

- United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refugees Vol. 3, No. 128, 2002 UNHCR Publication Refugees about the Somali Bantu" (PDF). Unhcr.org. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- "The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 October 2011. Retrieved 18 October 2011.

- Refugee Reports, November 2002, Volume 23, Number 8

- Campbell, Gwyn (2004). Abolition and Its Aftermath in the Indian Ocean Africa and Asia. Psychology Press. p. 121. ISBN 978-0203493021.

- Clarence-Smith, edited by William Gervase (1989). The Economics of the Indian Ocean slave trade in the nineteenth century (1. publ. in Great Britain. ed.). London, England: Frank Cass. ISBN 978-0714633596.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- International Business Publications, USA (7 February 2007). Central African Republic Foreign Policy and Government Guide (World Strategic and Business Information Library). 1. Int'l Business Publications. p. 47. ISBN 978-1433006210. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Alistair Boddy-Evans. Central Africa Republic Timeline – Part 1: From Prehistory to Independence (13 August 1960), A Chronology of Key Events in Central Africa Republic. About.com

- Catherine Coquery-Vidrovitch, in Les Collections de l'Histoire (April 2001) says:"la traite vers l'Océan indien et la Méditerranée est bien antérieure à l'irruption des Européens sur le continent"

- Lawrence, T.E. (1935). Seven Pillars of Wisdom. Garden City: Doubleday, Doran & Company, Inc. pp. 89, 159.

- Labbe, Theola (2004-01-11). "A Legacy Hidden in Plain Sight". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2015-04-29.

- Susan Beckerleg, translated by Salah Al Zaroo. "Hidden History, Secret Present: The Origins and Status of African Palestinians". The Health Promotion Research Unit and The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine. Retrieved 2015-04-29.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Manning, Patrick (1990). Slavery and African Life: Occidental, Oriental, and African Slave Trades. African Studies Series. London: Cambridge University Press.

- "Travels in Nubia, by John Lewis Burckhardt". Ebooks.adelaide.edu.au. 2015-08-25. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- Rice, Ed (1990). Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton: the secret agent who made the pilgrimage to Mecca, discovered the Kama Sutra, and brought the Arabian nights to the West. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. p. 203,280-281,289. ISBN 978-0684191379.

- The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death: Continued by a Narrative of His Last Moments and Sufferings, Obtained from His Faithful Servants, Chuma and Susi. Cambridge University Press. 15 September 2011. pp. 56, 62. ISBN 9781108032612. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

- Kwame Anthony Appiah; Henry Louis Gates (2005). Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African-American Experience, 5-Volume Set. Oxford University Press. p. 295. ISBN 978-0195170559.

- David Livingstone (2006). "The Last Journals of David Livingstone, in Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death". Echo Library. p.46. ISBN 1-84637-555-X

- The Last Journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa, from 1865 to His Death: Continued by a Narrative of His Last Moments and Sufferings, Obtained from His Faithful Servants, Chuma and Susi. Cambridge University Press. 1875. p. 352. Retrieved 25 April 2019.

the strangest disease i have sen in this country is brokenheartedness.

- "Swahili Coast". .nationalgeographic.com. 17 October 2002. Archived from the original on 6 December 2007. Retrieved 15 May 2015.

- Stanley Henry M., How I Found Livingstone; travels, adventures, and discoveries in Central Africa, including an account of four months' residence with Dr. Livingstone. (1871)

- "Slavery, Abduction and Forced Servitude in Sudan". US Department of State. 22 May 2002. Retrieved 20 March 2014.

- Reuters Editorial (2007-03-22). "Slavery still exists in Mauritania". Reuters.com. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- "Mauritanian MPs pass slavery law". BBC News. 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2016-03-23.

- "The Abolition season", BBC World Service

- Miers, Suzanne (21 March 2018). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Rowman Altamira. ISBN 9780759103405. Retrieved 21 March 2018 – via Google Books.

- "BBC – Religions – Islam: Slavery in Islam". bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 21 March 2018.

- From "Human Rights in Islam" by 'Allamah Abu Al-'A'la Mawdudi. Chapter 3, subsection 5 Archived 2007-02-03 at the Wayback Machine

- Alexander, J. (2001). "Islam, Archaeology and Slavery in Africa". World Archaeology. 33 (1): 44–60. doi:10.1080/00438240126645. JSTOR 827888.

- P.J. Bearman; Th. Bianquis; C.E. Bosworth; E. van Donzel; W.P. Heinrichs (eds.). "Abd". Encyclopaedia of Islam Online. Brill Academic Publishers. ISSN 1573-3912.

- Lewis, Bernard (1990). Race and Slavery in the Middle East. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0195062830.

- Murray Gordon (1989). Slavery in the Arab World. New York: New Amsterdam Books. p. 41. ISBN 9780941533300.

- Ehud R. Toledano (1998), Slavery and abolition in the Ottoman Middle East, University of Washington Press, pp. 13–4, ISBN 978-0-295-97642-6

- Hannoum, Abdelmajid (1 January 2003). "Translation and the Colonial Imaginary: Ibn Khaldûn Orientalist". History and Theory. 42 (1): 61–81. doi:10.1111/1468-2303.00230. JSTOR 3590803.

- A. J. Toynbee, Civilization on Trial, New York, 1948, p. 205

- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p9bI_5MKdQ0

- Please note : The numbers occurring in the source, and repeated here on Wikipedia include both Arab and European trade. M'bokolo, Elikia (April 1998). "A Hundred And Fifty Years After France Abolished Slavery: The impact of the slave trade on Africa". mondediplo.com. Le Monde diplomatique. Retrieved 3 June 2015.

- International Association for the History of Religions (1959), Numen, Leiden: EJ Brill, p. 131,

West Africa may be taken as the country stretching from Senegal in the west, to the Cameroons in the east; sometimes it has been called the central and western Sudan, the Bilad as-Sūdan, 'Land of the Blacks', of the Arabs

- Nehemia Levtzion, Randall Lee Pouwels, The History of Islam in Africa, (Ohio University Press, 2000), p.255.

- Pankhurst, Richard. The Ethiopian Borderlands: Essays in Regional History from Ancient Times to the End of the 18th Century (Asmara, Eritrea: Red Sea Press, 1997), pp.416

- Pankhurst. Ethiopian Borderlands, pp.432

- Pankhurst. Ethiopian Borderlands, pp.59 & 435

- Conlin, Joseph (2009), The American Past: A Survey of American History, Boston, MA: Wadsworth, p. 206, ISBN 978-0-495-57288-6, retrieved 10 October 2010

- McDaniel, Antonio (1995), Swing low, sweet chariot: the mortality cost of colonizing Liberia in the nineteenth century, University of Chicago Press, p. 11, ISBN 978-0-226-55724-3

- Emery Van Donzel, "Primary and Secondary Sources for Ethiopian Historiography. The Case of Slavery and Slave-Trade in Ethiopia," in Claude Lepage, ed., Études éthiopiennes, vol I. France: Société française pour les études éthiopiennes, 1994, pp.187-88.

- Doudou Diène (2001). From Chains to Bonds: The Slave Trade Revisited. Berghahn Books. p. 16. ISBN 978-1571812650. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- Mohamed Diriye Abdullahi, Culture and Customs of Somalia, (Greenwood Press: 2001), p.13

- James Hastings, Encyclopedia of Religion and Ethics Part 12: V. 12, (Kessinger Publishing, LLC: 2003), p.490

- Henry Louis Gates, Africana: The Encyclopedia of the African and African American Experience, (Oxford University Press: 1999), p.1746

- David D. Laitin, Politics, Language, and Thought: The Somali Experience, (University Of Chicago Press: 1977), p.52

- cite web |url=http://webdev.cal.org/development/co/bantu/sbpeop.html%5B%5D |title=The Somali Bantu: Their History and Culture – People |publisher=Cal.org |accessdate=21 February 2013 dead link|date=May 2018 |bot=InternetArchiveBot |fix-attempted=yes

- L. Randol Barker et al., Principles of Ambulatory Medicine, 7 edition, (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: 2006), p.633

- Jan Hogendorn and Marion Johnson (1986). The Shell Money of the Slave Trade. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521541107. Retrieved 29 April 2015.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Moorehead, Alan (1960), The White Nile, New York: Harper & Brothers, pp. 11–12, ISBN 9780060956394

- Luiz Felipe de Alencastro, "Traite", in Encyclopædia Universalis (2002), corpus 22, page 902.

- Ralph Austen, African Economic History (1987)

- Quoted in Ronald Segal's Islam's Black Slaves

- Adam Hochschild (Mar 4, 2001). "Human Cargo". New York Times. Retrieved Dec 20, 2012.

- Ronald Segal (2002), Islam's Black Slaves: The Other Black Diaspora, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978-0374527976

- Maddison, Angus. Contours of the world economy 1-2030 AD: Essays in macro-economic history. Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Botelho, Alyssa. "Empires and slave-trading left their mark on our genes". New Scientist.

- "SLAVE-TRADE – JewishEncyclopedia.com".

- Shaban, M.A. (1976). Islamic History: A New Interpretation, Vol 2: A.D. 750-1055 (A.H. 132-448). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 100 ff. ISBN 978-0-521-21198-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Edward A. Alpers, The East African Slave Trade (Berkeley 1967)

- Ibn Khaldun, The Muqaddimah, trans. F. Rosenthal, ed. N. J. Dawood (Princeton 1967)

- Murray Gordon, Slavery in the Arab World (New York 1989)

- Habeeb Akande, Illuminating the Darkness: Blacks and North Africans in Islam (Ta Ha 2012)

- Bernard Lewis, Race and Slavery in the Middle East (OUP 1990)

- Lal, K. S. (1994). Muslim slave system in medieval India. New Delhi: Aditya Prakashan.

- Patrick Manning, Slavery and African Life: Occidental, Oriental, and African Slave Trades (Cambridge 1990)

- Paul E. Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa (Cambridge 2000)

- Allan G. B. Fisher, Slavery and Muslim Society in Africa, ed. C. Hurst (London 1970, 2nd edition 2001)

- The African Diaspora in the Mediterranean Lands of Islam (Princeton Series on the Middle East) Eve Troutt Powell (Editor), John O. Hunwick (Editor) (Princeton 2001)

- Ronald Segal, Islam's Black Slaves (Atlantic Books, London 2002)

- Robert C. Davis, Christian Slaves, Muslim Masters: White Slavery in the Mediterranean, the Barbary Coast, and Italy, 1500-1800 (Palgrave Macmillan, London 2003) ISBN 978-1-4039-4551-8

- Doudou Diène (2001). From Chains to Bonds: The Slave Trade Revisited. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1571812650. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

External links

- Robert Davis. "British Slaves on the Barbary Coast". BBC. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- "Slavery in Islam". BBC. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- "Encyclopædia Britannica's Guide to Black History". www.britannica.com. Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on October 6, 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- iAbolish.ORG! American Anti-Slavery Group (AASG) - particular focus on North African slaves

- "Gaddafi apologizes for Arab slave traders". www.edition.presstv.ir. Press TV. Archived from the original on September 21, 2013. Retrieved 21 September 2013.