Lower Shawneetown

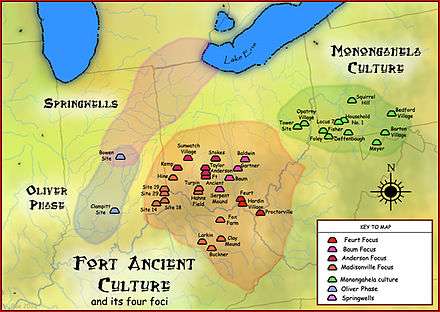

Lower Shawneetown (15Gp15), also known as the Bentley Site, Shannoah and Sonnontio, is a Late Fort Ancient culture Madisonville horizon (post 1400 CE) archaeological site overlain by an 18th-century Shawnee village; it is located within the Lower Shawneetown Archeological District, near South Portsmouth in Greenup County, Kentucky and Lewis County, Kentucky.[2] It was added to the National Register of Historic Places on April 28, 1983.[1]

Bronze historical marker near site | |

Approximate location within Kentucky today | |

| Location | South Portsmouth, Kentucky, Greenup County, Kentucky, |

|---|---|

| Region | Greenup County, Kentucky |

| Coordinates | 38°43′17.76″N 83°1′22.98″W |

| History | |

| Founded | Ca. 1733 |

| Abandoned | 1758 |

| Periods | Madisonville horizon, protohistoric |

| Cultures | Fort Ancient culture, Shawnee people |

| Architecture | |

| Architectural details | Number of monuments: |

Lower Shawneetown | |

| NRHP reference No. | 83002784[1] |

| Added to NRHP | April 28, 1983 |

Between about 1734 and 1758 Lower Shawneetown became a center for commerce and diplomacy, "a sort of republic populated by a diverse array of migratory peoples, from the Iroquois to the Delawares, and supplied by British traders, Lower Shawneetown had become a formidable threat to French ambitions. With a 'fairly large number of bad characters from various nations,' Lower Shawneetown posed a significant challenge to France and Great Britain alike. The community was less a village and more of a 'district extending along the wide Scioto River and narrower Ohio River floodplains and terraces.' It was a sprawling series of wickiups and longhouses ... French and British traders regarded Lower Shawneetown as one of two capitals of the Shawnee tribe."[3]

The town was destroyed by floods in November, 1758, and the population relocated to another site further up the Scioto River.[4]

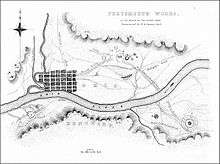

Portsmouth Earthworks, Group A

Built between 100 BCE and 500 CE by the Hopewell culture, the earthworks are a large ceremonial center located at the confluence of the Scioto and Ohio rivers.[5] A feature of the site is the "Old Fort Earthworks", a part of the Portsmouth Earthworks known as Group A.[6] The earthworks include a northern section consisting of a number of circular enclosures, two large horseshoe-shaped enclosures, and three sets of parallel-walled roads leading away from this location. One set of walls went to the southwest and may have been linked by an earthen causeway to a large square enclosure located on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River. Another set of walls went to the southeast, where it led to the Ohio River. The walls continued on the opposite side of the river and led to a complicated circular enclosure. The third set of walls went to the northwest for an undetermined distance.[7] Much of the site is now encompassed by the city of Portsmouth.

Fort Ancient settlement

The site is a 1.2 hectare village on the second flood terrace of the Ohio River, located across from the mouth of the Scioto River. It was excavated in the 1930s and was discovered to have had similar structures and building techniques as those found at another nearby Fort Ancient site, the Hardin Village Site located 13 kilometres (8.1 mi) up the Ohio.[8] Also found during the excavations were distinctive Madisonville horizon pottery,[9] including cordmarked, plain and grooved-paddle jars, as well as a variety of chert points, scrapers and ceremonial pipes.[2] The site was inhabited continuously from 1400 to about 1650 CE and probably had a population of 250 to 500 people living in long, rectangular houses covered with bark and shared by multiple families, as indicated by the several central hearths and interior partitions.[10]

Prior to the arrival of Europeans, the community engaged in trade with other villages, as evidenced by the presence in graves of ornamental shell gorgets made from the shells of marine mollusks harvested off the coasts of Florida and the Gulf of Mexico.[11][12] Fort Ancient residents probably obtained these shells by trading salt extracted from boiled brine.[13] Salt was still being produced as late as 1755 when the captive Mary Draper Ingles was employed in boiling brine before she escaped from Lower Shawneetown in October of that year.[14]

Many 18th century European trade goods were also found at the site, including gun spalls and gunflints, gun parts (sideplate, mainspring, ram pipes, and breech plugs), wire-wound and drawn glass beads, tinkling cones, a button, pendants, an earring, cutlery, kettle ears, a key, nails, chisels, hooks, a buckle, a Jew's harp, and pieces of a pair of iron scissors.[2][8][12]

The Fort Ancient residents of southern Ohio were very likely wiped out in the late seventeenth century by infectious diseases brought by Europeans, particularly measles, smallpox, and influenza. Graves from this period often contain multiple burials—from four to over a hundred individuals—reflecting a sudden increase in mortality typical of epidemics.[12] Depopulation may have been hastened by Iroquois raids during the Beaver Wars (1629-1701). The region was largely uninhabited when Lower Shawneetown was founded in the early 18th century.[10]

Shawnee village

.jpg)

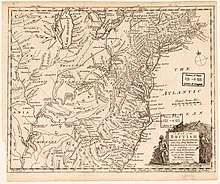

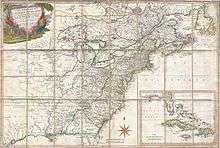

Established in the mid-1730s[4] at the confluence of the Scioto and Ohio Rivers, this was one of the earliest known Shawnee settlements on both sides of the Ohio River.[15] The Shawnee name of the town was not recorded, but scholars believe it may have been "Chalahgawtha," a Shawnee word meaning "principal place".[16] On English maps the town was labelled "the Lower Shawonese Town," "the lower Shawanees town," "Lower Shanna Town," "the Shannoah town," or "Shawnoah."[4] The French called it "Saint Yotoc"[17] (which may be a corruption of Scioto), "Sinhioto," "Sononito," "Sonnioto," "Scioto," and "Cenioteaux."[17][18]

Pressure from the growing European populations on the east coast of North America and in southern Canada had caused Native American populations to concentrate in the Ohio River Valley,[19] and Lower Shawneetown was situated at a convenient point, accessible to many communities living on tributaries of the Ohio River. The area had Iroquois, Delaware, Wyandot, and Miami communities within a few days' journey. The town also lay near the Seneca Trail, which was used by Cherokees and Catawbas, and it was surrounded by fertile, alluvial flatlands that were ideal for growing corn, beans, squash, gourds, tobacco, and sunflowers. The area adjacent to the town was rich in natural resources: a mosaic of mixed hardwood forests, flat grassy plains, canebrakes, salt and clear freshwater springs, home to deer, bear, elk, and bison. Wild plants and nut-bearing trees were abundant, and chert-bearing bedrock and clay river banks provided essential materials for tools and pottery.[16]

Although mainly a Shawnee village, the population included contingents of Seneca and Lenape.[3] After his visit to Lower Shawneetown in 1749, Céloron de Blainville wrote "this village [is] composed for the most part of Chavenois (Shawnee) and Iroquois of the Five Nations...men from the Sault St. Louis (Kahnawake), there are also some from the Lake of Two Mountains (Mohawks of Kanesatake), some Loups from the Miami (Munsee), and nearly all the nations from the territory of Enhault (Pays d'en Haut, the territory of New France to the west of Montreal)."[20]

The opportunity to trade for furs and to broker political alliances also attracted both British and French traders[16] and the town became a key center in dealings between Native American tribes and Europeans.[2][4][21] During the 1740s and 1750s, both the British and the French became increasingly concerned about the growing Native American settlements in the region, including Lower Shawneetown's neighbors, Logstown, Pickawillany, and Sandusky. Historian Richard White characterizes such "Indian republics" as multiethnic and autonomous, made up of a variety of smaller disparate social groups: village fragments, extended families, or individuals, often survivors of epidemics and refugees from conflicts with other Native Americans or with Europeans.[22]

In 1749 Joseph Pierre de Bonnecamps estimated that the entire town had about 60 cabins,[23] but by 1751, the town consisted of 40 houses on the Kentucky side and 100 houses on the Ohio side, as well as a 90 feet (27 m) long council house.[15] Including its 300 warriors, the town may have had a total population of between 1,200[21] and 1,500.[24] In 1753, the Shawnee relocated part of the village on the east bank of the Scioto River and on the Kentucky side of the Ohio River after a flood destroyed much of the original village, which had been situated on the Scioto River's west bank.[8][25]

Peter Chartier

In April 1745 Peter Chartier and about 400 Shawnees took refuge in Lower Shawneetown after defying Governor Patrick Gordon in a conflict over the sale of rum to the Shawnees. Chartier opposed the sale of alcohol in Native American communities and threatened to destroy any shipments of rum that he found. He persuaded members of the Pekowi Shawnee to leave Pennsylvania and migrate south. A French trader in Lower Shawneetown witnessed Chartier's Shawnees performing a two-day "Death Feast,"[26] a ceremony conducted before abandoning a village.[3] After staying in Lower Shawneetown for a few weeks they proceeded into Kentucky to found the community of Eskippakithiki.[4]

Visits by French soldiers

The earliest reference to the town is found in a July 27, 1734 letter by François-Marie Bissot, Sieur de Vincennes, describing an English trader's warehouse (probably that of George Croghan and William Trent) in "the home of the Shawnees on the Ohio River."[4] The French had focused much attention on Canada, allowing English traders to establish themselves in the Ohio Valley, but in the late 1730s the French began trying to correct this by sending expeditions into the region.

The earliest eyewitness account is a report by Charles III Le Moyne, Baron de Longueuil from July 1739. A French military expedition made up of 123 French soldiers and 319 Native American warriors from Quebec, under the command of Le Moyne, was on its way to help defend New Orleans from the Chickasaw, who were attacking the city on behalf of England. While on their journey down the Ohio River towards the Mississippi River, they met with local chiefs in a village on the banks of the Scioto, which was probably Lower Shawneetown.[4]

Concerned that this vibrant community would be readily influenced by trade goods supplied by the British, the Governor of New France, Charles de la Boische, Marquis de Beauharnois sent emissaries to Lower Shawneetown in 1741 to try to persuade the Shawnees to relocate to Detroit, but the proposal was rejected.[3]

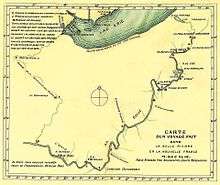

Visit by Céloron de Blainville

In the summer of 1749 Pierre Joseph Céloron de Blainville, leading a force of eight officers, six cadets, an armorer, 20 soldiers, 180 Canadians, 30 Iroquois and 25 Abenakis,[17] moved down the Ohio River on his "lead plate expedition," burying lead plates at six locations where major tributaries entered the Ohio.[20] The plates were inscribed to claim the area for France. Céloron also sought out British traders and warned them to leave this territory which belonged to France.[16] Céloron arrived at the town of "St. Yotoc" on 21 August, where a Lenape Indian they met informed them that the town consisted of "about 80 cabins there, and perhaps 100." Father Bonnecamps, the geographer of Celoron's expedition, wrote:

The situation of the village of the Chaouanons is quite pleasant, at least, it is not masked by the mountains, like the other villages through which we had passed. The Sinhioto River, which bounds it on the west, has given it its name. It is composed of about sixty cabins. The Englishmen there numbered five.[23]

Hearing that a French military force was approaching, the inhabitants had hastily erected a stockade. Céloron described it as a "stone fort, strongly built and in good condition for their defense." He sent a delegation of Kahnawake and Abenaki Indians led by Philippe-Thomas Joncaire de Chabert, but as they approached the town, warriors manning the stockade fired three shots at them, all of which struck the French flag they were carrying. Shortly afterwards, a canoe bearing a white flag approached Céloron's camp, and Shawnee and Iroquois leaders from Lower Shawneetown met with Céloron. They apologized for the shots fired at the French delegation, saying that they had feared that the French were planning to attack the town.[20]

The Shawnees invited him to enter the town and address them in their council-house, but Céloron was wary of being ambushed: "I was aware of the weakness of my detachment; two-thirds were recruits who had never made an attack...[The Indians] being much displeased, it would have been a great imprudence to go to their village."[20] Céloron negotiated with the leaders of the town for two days but he was unable to persuade them to abandon their loyalty to the English, as "the cheap merchandise which the English furnished was [a] very seducing motive for them to remain attached to the latter." On 25 August he summoned the five Pennsylvania traders who were then living in the town and ordered them to leave, stating that "they had no right to trade or aught else on the [Ohio] River."[20] Céloron considered plundering their goods, but as he was confronted by a large and well-armed Shawnee force, he desisted and continued on his way.[27] Céloron's expedition was intended to impress the inhabitants of the Ohio River Valley with the capability of the French to maintain control over the region, but it met with defiance and resulted in a weakening of the French position.[22]

Commerce with British traders

.jpg)

William Trent established a storehouse in Lower Shawneetown sometime around 1734, and the Shawnees kept it secure in order to encourage further trade with the British. Between 1748 and 1751 the British traders Andrew Montour and George Croghan visited the town three times while attempting to strengthen the alliance between the Shawnees and the British government.[4] When Céloron visited the town in August 1749, he found five English traders "established...in the village and well sustained by the Indians."[20] In 1750, the Ohio Company hired Christopher Gist, a skilled woodsman and surveyor, to explore the Ohio Valley in order to identify lands for potential settlement. He surveyed the Kanawhan Region and the Ohio Valley tributaries in 1750–1751 and 1753. In January 1751 Gist, Croghan and Montour, accompanied by Robert Callender, visited the town. Gist's journal entry from January 29, 1751 states:

Tuesday 29.— Set out ... to the Mouth of Sciodoe Creek opposite to the Shannoah Town, here we fired our Guns to alarm the Traders, who soon answered, and came and ferryed Us over to the Town — The Land about the Mouth of Sciodoe Creek is rich but broken fine Bottoms upon the River & Creek. The Shannoah Town is situate upon both Sides the River Ohio, just below the Mouth of Sciodoe Creek, and contains about 300 Men, there are about 40 Houses on the S Side of the River and about 100 on the N Side, with a Kind of State-House of about 90 Feet long, with a light Cover of Bark in which they hold their Councils.

The journal terminates with a detailed description of a festival Gist witnessed during his stay in Lower Shawneetown.[29]

When the town was destroyed by flooding in 1753, British traders relocated with the rest of the town's population, intending to maintain their profitable businesses. In the 1918 edition of Narrative of the Life of Mrs. Mary Jemison, George P. Donehoo, Secretary of the Pennsylvania Historical Commission, records:

Shortly after 1753 the village...was destroyed by a flood. The town was then built up on the south side of the Ohio. George Croghan, William Trent and other Indian traders had trading houses at this place. Croghan's large store...was destroyed by the French and Indians in 1754.[25]:339–340

Archeological evidence shows that, by the 1750s, trade had transformed the lives of the residents of the town. Traders brought guns, metal tools, knives, saddles, hatchets, glass and ceramic beads, brooches, strouds (a kind of coarse blanket), ruffled and plain shirts, coats, clay tobacco pipes, brass and iron pots, and rum to trade for the furs and skins of deer, elk, bison, bear, beaver, raccoon, fox, wildcat, muskrat, mink and fisher. Town residents wore European-style glass beads, silver earrings, armbands, and brooches, rather than traditional Native American beads and pendants made from shell, animal teeth, or animal bone. Cloth matchcoats, blankets, skirts, and shirts supplemented moccasins and garments manufactured from animal skins.[16]

Lower Shawneetown's size and connections to neighboring communities allowed traders to establish storehouses for incoming and outgoing goods, managed by European men who lived in the town year-round and sometimes married Native American women. These trading posts attracted local hunters to bring skins and furs to the town, meaning that a post in Lower Shawneetown could do profitable business with dozens of villages without requiring the traders themselves to travel, as they had done previously. The town's location on the Ohio River allowed traders to send furs and skins by canoe up to Logstown, where they were taken by packhorses over the mountains, transferred into wagons for a fourteen-day journey to Philadelphia and then shipped to London.[16]

Captives

At least five captives taken during raids on American pioneer settlements are known to have lived in or visited Lower Shawneetown. Catherine Gougar (1732–1801) was kidnapped in 1744 from her home in Berks County, Pennsylvania and lived in the town for five years.[30][31] She was eventually sold to French-Canadian traders and after two more years in Canada, managed to return home in 1751.[32]

Mary Draper Ingles (1732–1815) was kidnapped during the Draper's Meadow massacre in July 1755 and taken to Lower Shawneetown. French traders were living in the town at that time, selling cloth, and Ingles demonstrated her skill in sewing shirts, for which she was paid "in goods."[33] She stayed in the town for about three weeks before being taken to Big Bone Lick to make salt by boiling brine. She and another captive escaped in mid-October, 1755, and walked several hundred miles to return home.[14][34] An article in the New-York Mercury of 16 February 1756, describing Mary's capture and escape mentions that, while in Lower Shawneetown, she saw "a considerable Number of English Prisoners, who have been taken Captives from the Frontiers of Virginia."[35]

The same newspaper article states that she saw Captain Samuel Stalnaker, who had been captured during a raid on Holston River in Tennessee on June 18, 1755.[35] A letter from Governor Robert Dinwiddie dated 21 June 1756, reports that he later escaped, although no details are given.[36][37][38]

Moses Moore and Isham Bernat were captured in Virginia and taken to Lower Shawneetown in the spring of 1758. Bernat was living at his plantation near the Irwin River when he was taken prisoner by a party of Shawnees, Wyandots, Delawares and Mingoes on 31 March 1758. Moore was hunting beaver in Augusta County when he was taken prisoner by a party of Wyandots in April, 1758. They were held for a few days in Lower Shawneetown before escaping and walking for 23 days to reach Pittsburgh.[39][4]

Destruction and relocation

John P. Hale states that in about November, 1758,

... a very extreme, if not unprecedented, flood in the rivers swept off a greater part of the town, and it was never rebuilt at that place; but the tribe moved its headquarters ... up the Scioto and built up successively the Old and New Chillicothe, or Che-le-co-the Towns. There remained a Shawnee village at the mouth of the Scioto, which was then built upon the other side, the present site of the city of Portsmouth.[40]

When Mary Jemison, a captive of the Seneca, spent the winter at the mouth of the Scioto River in 1758–1759, Lower Shawneetown had been abandoned and relocated further up the Scioto River.[25]:360–361 It is possible that this new village was Chalahgawtha at the site of present-day Chillicothe, Ohio.[4]

George P. Donehoo says:

In 1758, the first year of Mary Jemison's going there, the Shawnee moved their town (the Lower Shawnee Town) from the mouth of the Scioto to the upper plains of the Scioto, sending for the Shawnees of Logstown to join them there and possibly also for the Shawnees of the Shawnee Town at the mouth of the Great Kanawha to do the same.[25]

Legacy

A. Gwynn Henderson argues that multiethnic "supervillages" such as Lower Shawneetown might be considered early Native American city-states because of their political autonomy and the new opportunities they created for different tribes as well as for the interaction of Native Americans with Europeans:

"The intermarriage and ethnic diversity within these settlements created a multitude of new kinship and social situations, adding layers of ethnic, social, and village relationships. Thus, the potential for factionalism and the development of different European responses may have been even greater in these villages than in traditional single-ethnic villages. As autonomous communities, these republics existed politically beyond the control of the French, British, and even the Six Nations at Onondaga, and their residents were responsible only to themselves. Thus, they had the freedom to make decisions based on their own needs, traditions, and cultural proscriptions, and they could ally themselves with whomever they wished or change their alliances when it suited their needs.[16]

Lower Shawneetown's diversity prevented it from operating as a political entity, however. Independent factions, themselves often divided, responded individually to events, to the frustration of European envoys. Community leaders were rarely able to unify a majority in backing policy decisions, which prevented Europeans from establishing firm diplomatic relations with Lower Shawneetown as they did (to some extent) at Logstown.[16]

Lower Shawneetown Archeological District

The Lower Shawneetown Archeological District, in Greenup County, Kentucky and Lewis County, Kentucky near South Portsmouth, is a 335 acres (1.36 km2) historic district which was listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1985.[41]

It is Address restricted[42].

It includes the Lower Shawneetown village site, graves/burials, and more in six contributing sites and was listed for its information potential.[1]

See also

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. 2010-11-02. Archived from the original on 2013-02-20.

- Sharp, William E. (1996). "Chapter 6: Fort Ancient Farmers". In Lewis, R. Barry (ed.). Kentucky Archaeology. University Press of Kentucky. pp. 170–176. ISBN 0-8131-1907-3.

- Stephen Warren, Worlds the Shawnees Made: Migration and Violence in Early America, UNC Press Books, 2014 ISBN 1469611732

- Charles Augustus Hanna, The Wilderness Trail: Or, The Ventures and Adventures of the Pennsylvania Traders on the Allegheny Path, Volume 1, Putnam's sons, 1911

- Case, D. Troy and Christopher Carr, eds. The Scioto Hopewell and their Neighbors: Bioarchaeological Documentation and Cultural Understanding. New York, NY: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers, 2008

- Woodward, Susan L., and Jerry N. McDonald. Indian Mounds of the Middle Ohio Valley: A Guide to Mounds and Earthworks of the Adena, Hopewell, Cole, and Fort Ancient People. Lincoln: The University of Nebraska Press, 2002

- Ephraim George Squier; Edwin Hamilton Davis (1848). Ancient Monuments of the Mississippi Valley. Smithsonian Institution. pp. 179–187.

- David Pollack and A. Gwynn Henderson, "A Preliminary Report on the Contact Period Occupation at Lower Shawneetown (l5GP15), Greenup County, Kentucky," paper presented at the 58th Annual Meeting of the Central States Anthropological Society on April 9, 1982.

- Michelle M. Davidson, "Preliminary mineralogical and chemical study of Pre-Madisonville and Madisonville horizon Fort Ancient ceramics," Norse Scientist, Vol. 1, Issue 1, April 2003; Northern Kentucky University.

- A. Gwynn Henderson, David Pollack, "A Native History of Kentucky: Selections from Chapter 17: Kentucky," in Native America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia, edited by Daniel S. Murphree, Volume 1, pages 393-440; Greenwood Press, Santa Barbara, CA. 2012

- Dubin, Lois Sherr (1999). North American Indian Jewelry and Adornment: From Prehistory to the Present. New York: Harry N. Abrams. ISBN 978-0-8109-3689-8.

- A. Gwynn Henderson, "Dispelling the Myth: Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Indian Life in Kentucky," The Register of the Kentucky Historical Society, Vol. 90, No. 1, The KentuckyImage (Bicentennial Issue), pp. 1-25, Kentucky Historical Society

- Ian W. Brown, Salt and the Eastern North American Indian: An Archaeological Study, Cambridge, Mass., 1980.

- Jennings, Gary (August 1968). "An Indian Captivity". American Heritage Magazine. 19 (5).

- Foster, Emily (2000-08-24). The Ohio Frontier: An Anthology of Early Writings. The University Press of Kentucky. p. 13. ISBN 978-0-8131-0979-4.

- A. Gwynn Henderson, "The Lower Shawnee Town on Ohio: Sustaining Native Autonomy in an Indian "Republic"." In Craig Thompson Friend, ed., The Buzzel about Kentuck: Settling the Promised Land, University Press of Kentucky, 1999; pp. 25-56. ISBN 0813133394

- O. H. Marshall, "De Celoron's Expedition to the Ohio in 1749, Magazine of American History, March, 1878, p. 146.

- Ermine Wheeler Voegelin, An Ethnohistorical Report on the Indian Use and Occupancy of Royce Area 11, Ohio and Indiana, 2 vols. (New York: Garland Press, 1974), vol 1, p. 261.

- Jerry E. Clark, "A System Model of Shawnee Indian Migration," Transactions of the Nebraska Academy of Sciences, Vol VII, 1979.

- "Celeron de Bienville". Ohio History Central. Ohio Historical Society. Retrieved 2019-05-13.

- Gordon Calloway, The Shawnees and the War for America, The Penguin library of American Indian history; Penguin, 2007. ISBN 0670038628

- Richard White, The Middle Ground: Indians, Empires, and Republics in the Great Lakes Region, 1650–1815 Cambridge studies in North American Indian history, Cambridge University Press, 1991. ISBN 1139495682

- "Relation du voyage de la Belle Rivière faite en 1749, sous les ordres de M. de Céloron," in Reuben Gold Thwaites, ed., The Jesuit Relations and Allied Documents, 73 vols. Cleveland: Burrow Brothers, 1896-1901, vol. 69; pp. 181-83.

- Henry F. Dobyns, William R. Swagerty, Their Number Become Thinned: Native American Population Dynamics in Eastern North America, ACLS Humanities E-Book; Native American historic demography series; Newberry Library. Center for the History of the American Indian, University of Tennessee Press, 1983. ISBN 0870494007

- James Everett Seaver, Charles Delamater Vail A Narrative of the Life of Mary Jemison: The White Woman of the Genessee, American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society, 1918.

- Guy Lanoue, "Female Rituals of the Iroquois," Université de Montréal.

- Ian K. Steele, Setting All the Captives Free: Capture, Adjustment, and Recollection in Allegheny Country, Vol. 71 of McGill-Queen's Native and Northern Series; McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP, 2013. ISBN 0773589899

- Annosanah: A Novel Based on the Life of Christopher Gist

- The Journal of Christopher Gist, 1750–1751 From Lewis P. Summers, 1929, Annals of Southwest Virginia, 1769–1800. Abingdon, VA.

- Caroline S. Coldren, "Catherine Gougar Goodman," monograph, April 1940; Family History Library.

- Catherine Gougar Goodman

- Frank Warner, "Catherine Gougar," Ohio History, Volume 31; Ohio Historical Society., 1922.

- Ingles, John (1824). The Narrative of Col. John Ingles Relating to Mary Ingles and the Escape from Big Bone Lick (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-13. Retrieved 2019-05-10.

- "James Duvall, "Mary Ingles and the Escape from Big Bone Lick," Boone County Public Library, 2009" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-03-13. Retrieved 2014-04-21.

- "Contemporary newspaper account of Mary Ingles' escape" (PDF). Mercury. New York. 26 January 1756. p. 3 col. 1.

- Robert A. Brock, ed. The official records of Robert Dinwiddie, Lieutenant-governor of the Colony of Virginia, 1751-1758, Richmond: The Society, 1883-84; p. 447.

- Lewis Preston Summers, History of Southwest Virginia, 1746-1786, Washington County, 1777-1870, J.L. Hill Print. Company, 1903.

- Indian Attacks of 1755-1758 in Augusta County, VA

- Samuel Hazard, ed. Pennsylvania Archives: 1st Series: Selected and Arranged from Original Documents in the Office of the Secretary of the Commonwealth, Conformably to Acts of the General Assembly, February 15, 1851, and March 1, 1852. Pennsylvania, Secretary of the Commonwealth. J. Severns, 1853; pp. 632-33.

- John P. Hale, Trans-Allegheny pioneers : historical sketches of the first white settlements west of the Alleghenies, Cincinnati: The Graphic Press, 1886.

- "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Lower Shawneetown Archeological District". National Park Service. With accompanying pictures

- Federal and state laws and practices restrict general public access to information regarding the specific location of this resource. In some cases, this is to protect archeological sites from vandalism, while in other cases it is restricted at the request of the owner. See: Knoerl, John; Miller, Diane; Shrimpton, Rebecca H. (1990), Guidelines for Restricting Information about Historic and Prehistoric Resources, National Register Bulletin, National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, OCLC 20706997.