Lockheed P-3 Orion

The Lockheed P-3 Orion is a four-engine turboprop anti-submarine and maritime surveillance aircraft developed for the United States Navy and introduced in the 1960s. Lockheed based it on the L-188 Electra commercial airliner.[4] The aircraft is easily distinguished from the Electra by its distinctive tail stinger or "MAD Boom", used for the magnetic detection of submarines.

| P-3 Orion | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| A P-3C of the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force | |

| Role | Maritime patrol aircraft |

| National origin | United States |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed Lockheed Martin Kawasaki Heavy Industries |

| First flight | November 1959 |

| Introduction | August 1962 |

| Status | Active |

| Primary users | United States Navy Royal New Zealand Air Force Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force Royal Australian Air Force Republic of Korea Navy |

| Produced | 1961–1990[2] |

| Number built | Lockheed – 650, Kawasaki – 107, Total – 757[3] |

| Unit cost |

US$36 million (FY1987) |

| Developed from | Lockheed L-188 Electra |

| Variants | Lockheed AP-3C Orion Lockheed CP-140 Aurora Lockheed EP-3 Lockheed WP-3D Orion |

| Developed into | Lockheed P-7 |

Over the years, the aircraft has seen numerous design developments, most notably in its electronics packages. Numerous navies and air forces around the world continue to use the P-3 Orion, primarily for maritime patrol, reconnaissance, anti-surface warfare and anti-submarine warfare. A total of 757 P-3s have been built, and in 2012, it joined the handful of military aircraft including the Boeing B-52 Stratofortress, Boeing KC-135 Stratotanker, Lockheed C-130 Hercules and the Lockheed U-2 that have seen over 50 years of continuous use by the United States military. The Boeing P-8 Poseidon will eventually replace the U.S. Navy's remaining P-3C aircraft.

Development

Origins

In August 1957 the U.S. Navy called for proposals for replacement of the piston-engined Lockheed P2V Neptune (later redesignated P-2) and Martin P5M Marlin (later redesignated P-5) with a more advanced aircraft to conduct maritime patrol and anti-submarine warfare. Modifying an existing aircraft was expected to save on cost and to allow rapid introduction into the fleet. Lockheed suggested a military version of its L-188 Electra, then still in development and yet to fly. In April 1958 Lockheed won the competition and was awarded an initial research-and-development contract in May.[4]

Lockheed modified the prototype YP3V-1/YP-3A, Bureau Number (BuNo) 148276 from the third Electra airframe c/n 1003.[5] The first flight of the aircraft's aerodynamic prototype, originally designated YP3V-1, took place on 19 August 1958. While based on the same design philosophy as the Lockheed L-188 Electra, the aircraft differed structurally: it had 7 feet (2.1 m) less fuselage forward of the wings with an opening bomb bay, and a more pointed nose radome, a distinctive tail "stinger" for detection of submarines by magnetic anomaly detector, wing hardpoints, and other internal, external, and airframe-production technique enhancements.[4] The Orion has four Allison T56 turboprops which give it a top speed of 411 knots (761 km/h; 473 mph) comparable to the fastest propeller fighters, or even to slow high-bypass turbofan jets such as the Fairchild Republic A-10 Thunderbolt II or the Lockheed S-3 Viking. Similar patrol aircraft include the Soviet Ilyushin Il-38, the French Breguet Atlantique and the British jet-powered Hawker Siddeley Nimrod (based on the de Havilland Comet).

The first production version, designated P3V-1, was launched on 15 April 1961. Initial squadron deliveries to Patrol Squadron Eight (VP-8) and Patrol Squadron Forty Four (VP-44) at Naval Air Station Patuxent River, Maryland, began in August 1962. On 18 September 1962 the U.S. military transitioned to a unified designation system for all services, with the aircraft being renamed the P-3 Orion.[4] Paint schemes have changed from early 1960s gloss seaplane gray and white to mid-1960s/1970s/1980s/early 1990s gloss white and gray, to mid-1990s flat finish low-visibility gray with fewer and smaller markings. In the early 2000s the paint scheme changed to its current overall gloss gray finish with the original full-size color markings. However, large-size Bureau Numbers on the vertical stabilizer and squadron designations on the fuselage remained largely omitted.[6]

Further developments

In 1963, the U.S. Navy Bureau of Weapons (BuWeps) contracted Univac Defense Systems Division of Sperry-Rand to engineer, build and test a digital computer (then in its infancy) to interface with the many sensors and newly developing display units of the P-3 Orion. Project A-NEW was the engineering system which, after several early trials, produced the engineering prototype, the CP-823/U, Univac 1830, Serial A-1, A-NEW MOD3 Computing System. The CP-823/U was delivered to the Naval Air Development Center (NADC) at Johnsville, Pennsylvania in 1965, and directly led to the production computers later equipped on the P-3C Orion.[7]

Three civilian Electras were lost in fatal accidents between February 1959 and March 1960. Following the third crash the FAA restricted the maximum speed of Electras until the cause could be determined. After an extensive investigation, two of the crashes (in September 1959 and March 1960) were found to be caused by insufficiently strong engine mounts, unable to damp a whirling motion that could affect the outboard engines. When the oscillation was transmitted to the wings, a severe vertical vibration escalated until the wings were torn from the aircraft.[8][9] The company implemented an expensive modification program, labelled the Lockheed Electra Achievement Program or LEAP, in which the engine mounts and wing structures supporting the mounts were strengthened, and some wing skins replaced with thicker material. All the surviving Electras of the 145 built at that time were modified at Lockheed's expense at the factory, the modifications taking 20 days for each aircraft. The changes were incorporated in subsequent aircraft as they were built.[8]

Sales of Electra airliners were limited, as Lockheed's technical fix did not serve to completely erase the aircraft's "jinxed" reputation, in an era in which turboprop-powered aircraft were being replaced by faster jets.[10] In a military role where fuel efficiency was more valued than speed, the Orion has been in service over 50 years after its 1962 introduction. Although surpassed in production longevity by the Lockheed C-130 Hercules, 734 P-3s were produced through 1990.[2][11][12] Lockheed Martin opened a new P-3 wing production line in 2008 as part of its Service Life Extension Program (ASLEP) for delivery in 2010. A complete ASLEP replaces the outer wings, center wing lower section and horizontal stabilizers with newly built parts.[13]

In the 1990s, during a U.S. Navy attempt to identify a successor aircraft to the P-3, the improved P-7 was selected over a navalized variant of the twin turbofan-powered Boeing 757, but this program was subsequently cancelled. In a second program to procure a successor, the advanced Lockheed Martin Orion 21, another P-3 derived aircraft, lost out to the Boeing P-8 Poseidon, a Boeing 737 variant, which entered service in 2013.

Design

The P-3 has an internal bomb bay under the front fuselage which can house conventional Mark 50 torpedoes or Mark 46 torpedoes and/or special (nuclear) weapons. Additional underwing stations, or pylons, can carry other armament configurations including the AGM-84 Harpoon, AGM-84E SLAM, AGM-84H/K SLAM-ER, the AGM-65 Maverick, 127 millimetres (5.0 in) Zuni rockets, and various other sea mines, missiles, and gravity bombs. The aircraft also had the capability to carry the AGM-12 Bullpup guided missile until that weapon was withdrawn from U.S./NATO/Allied service.[14]

The P-3 is equipped with a magnetic anomaly detector (MAD) in the extended tail. This instrument is able to detect the magnetic anomaly of a submarine in the Earth's magnetic field. The limited range of this instrument requires the aircraft to be near the submarine at low altitude. Because of this, it is primarily used for pinpointing the location of a submarine immediately prior to a torpedo or depth bomb attack. Due to the sensitivity of the detector, electromagnetic noise can interfere with it, so the detector is placed in P-3's fiberglass tail stinger (MAD boom), far from other electronics and ferrous metals on the aircraft.[15]

Crew complement

The crew complement varies depending on the role being flown, the variant being operated, and the country that is operating the type. In U.S. Navy service, the normal crew complement was 12 until it was reduced to its current complement of 11 in the early 2000s when the in-flight ordnanceman (ORD) position was eliminated as a cost-savings measure and the ORD duties assumed by the in-flight technician (IFT). Data for U.S. Navy P-3C only.

Officers:

- three Naval Aviators

- Patrol Plane Commander (PPC)

- Patrol Plane 2nd Pilot (PP2P)

- Patrol Plane 3rd Pilot (PP3P)

- two Naval Flight Officers

- Patrol Plane Tactical Coordinator (PPTC or TACCO)

- Patrol Plane Navigator/Communicator (PPNC or NAVCOM)

NOTE: NAVCOM on P-3C only; USN P-3A and P-3B series had an NFO Navigator (TACNAV) and an enlisted Airborne Radio Operator (RO)

Enlisted Aircrew:

- two enlisted Aircrew Flight Engineers (FE1 and FE2)

- three enlisted Sensor Operators

- Radar/MAD/EWO (SS-3)

- two Acoustic (SS-1 and SS-2)

- one enlisted In-Flight Technician (IFT)

- one enlisted Aviation Ordnanceman (ORD position no longer used on USN crews; duties assumed by IFT.)

The senior of either the PPC or TACCO will be designated as the aircraft Mission Commander (MC).

Engine loiter shutdown

Once on station, one engine is often shut down (usually the No. 1 engine – the left outer engine) to conserve fuel and extend the time aloft and/or range when at low level. It is the primary candidate for loiter shutdown because it has no generator. Eliminating the exhaust from engine 1 also improves visibility from the aft observer station on the left side of the aircraft.

On occasion, both outboard engines can be shut down, weight, weather, and fuel permitting. Long deep-water, coastal or border patrol missions can last over 10 hours and may include extra crew. The record time aloft for a P-3 is 21.5 hours, undertaken by the Royal New Zealand Air Force's No. 5 Squadron in 1972.

Operational history

United States

Developed during the Cold War, the P-3's primary mission was to localize Soviet Navy ballistic missile and fast attack submarines detected by undersea surveillance systems and eliminate them in the event of full-scale war.[16][17] At its height, the U.S. Navy's P-3 community consisted of twenty-four active duty "Fleet" patrol squadrons home based at air stations in the states of Florida and Hawaii as well as bases which formerly had P-3 operations in Maryland, Maine, and California. There were also thirteen Naval Reserve patrol squadrons identical to their active duty "Fleet" counterparts, said Reserve "Fleet" squadrons being based in Florida, Pennsylvania, Maryland, Michigan, Massachusetts (later relocated to Maine), Illinois, Tennessee, Louisiana, California and Washington. Two Fleet Replacement Squadrons (FRS), also called "RAG" squadrons (from the historic "Replacement Air Group" nomenclature) were located in California and Florida. The since-deactivated VP-31 in California provided P-3 training for the Pacific Fleet, while VP-30 in Florida performed the task for the Atlantic Fleet. These squadrons were also augmented by a test and evaluation squadron in Maryland, two additional test and evaluation units that were part of an air development center in Pennsylvania and a test center in California, an oceanographic development squadron in Maryland, and two active duty "special projects" units in Maine and Hawaii, the latter being slightly smaller than a typical squadron.

Reconnaissance missions in international waters led to occasions where Soviet fighters would "bump" a P-3, either operated by the U.S. Navy or other operators such as the Royal Norwegian Air Force. On 1 April 2001, a midair collision between a United States Navy EP-3E ARIES II signals surveillance aircraft and a People's Liberation Army Navy J-8II jet fighter-interceptor resulted in an international dispute between the U.S. and the People's Republic of China (PRC).[18]

More than 40 combatant and noncombatant P-3 variants have demonstrated the rugged reliability displayed by the platform flying 12-hour plus missions 200 ft (61 m) over salt water while maintaining an excellent safety record. Versions have been developed for the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) for research and hurricane hunting/hurricane wall busting, for the U.S. Customs Service (now U.S. Customs and Border Protection) for drug interdiction and aerial surveillance mission with a rotodome adapted from the Grumman E-2 Hawkeye or an AN/APG-66 radar adapted from the General Dynamics F-16 Fighting Falcon, and for NASA for research and development.

The U.S. Navy remains the largest P-3 operator, currently distributed between a single fleet replacement (i.e., "training") patrol squadron in Florida (VP-30), 12 active duty patrol squadrons distributed between bases in Florida, Washington and Hawaii, two Navy Reserve patrol squadrons in Florida and Washington, one active duty special projects patrol squadron (VPU-2) in Hawaii, and two active duty test and evaluation squadrons. One additional active duty fleet reconnaissance squadron (VQ-1) operates the EP-3 Aries signals intelligence (SIGINT) variant at Naval Air Station Whidbey Island, Washington.

In January 2011, the U.S. Navy revealed that P-3s have been used to hunt down "third generation" narco subs.[19] This is significant because as recently as July 2009, fully submersible submarines have been used in smuggling operations.[20] As of November 2013, the US Navy began phasing out the P-3 in favor of the newer and more advanced Boeing P-8 Poseidon.

In May 2020, Patrol Squadron 40 completed the transition to the P-8, marking the retirement of the P-3C from U.S. Navy active duty service. The last of the active-duty P-3Cs, aircraft 162776, was also delivered to the Naval Aviation Museum in Pensacola, Florida. Two Navy Reserve squadrons and Air Test and Evaluation Squadron 30 continue to fly the P-3C, with final phaseout of the aircraft expected in 2023.[21]

In Cuba

In October 1962, P-3A aircraft flew several blockade patrols in the vicinity of Cuba. Having just recently joined the operational Fleet earlier that year, this was the first employment of the P-3 in a real world "near conflict" situation.

In Vietnam

Beginning in 1964, forward deployed P-3 aircraft began flying a variety of missions under Operation Market Time from bases in the Philippines and Vietnam. The primary focus of these coastal patrols was to stem the supply of materials to the Viet Cong by sea, although several of these missions also became overland "feet dry" sorties. During one such mission, a small caliber artillery shell passed through a P-3 without rendering it mission incapable. The only confirmed combat loss of a P-3 also occurred during Operation Market Time. In April 1968, a U.S. Navy P-3B of VP-26 was downed by anti-aircraft fire in the Gulf of Thailand with the loss of the entire crew. Two months earlier, in February 1968, another one of VP-26's P-3B aircraft was operating in the same vicinity when it crashed with the loss of the entire crew. Originally attributed to an aircraft mishap at low altitude, later conjecture is that this aircraft may have also fallen victim to anti-aircraft artillery (AAA) fire from the same source as the April incident.[22]

In Iraq

On 2 August 1990, Iraq invaded Kuwait and was poised to strike Saudi Arabia. Within 48 hours of the initial invasion, U.S. Navy P-3C aircraft were among the first American forces to arrive in the area. One was a modified platform with a prototype system known as "Outlaw Hunter". Undergoing trials in the Pacific after being developed by Tiburon Systems, Inc. for NAVAIR's PMA-290 Program Office, "Outlaw Hunter" was testing a specialized over-the-horizon targeting (OTH-T) system package when it responded. Within hours of the start of the coalition air campaign, "Outlaw Hunter" detected a large number of Iraqi patrol boats and naval vessels attempting to move from Basra and Umm Qasr to Iranian waters. "Outlaw Hunter" vectored in strike elements which attacked the flotilla near Bubiyan Island destroying 11 vessels and damaging scores more. During Desert Shield, a P-3 using infrared imaging detected a ship with Iraqi markings beneath freshly-painted bogus Egyptian markings trying to avoid detection. Several days before the 7 January 1991 commencement of Operation Desert Storm, a P-3C equipped with an APS-137 Inverse Synthetic Aperture Radar (ISAR) conducted coastal surveillance along Iraq and Kuwait to provide pre-strike reconnaissance on enemy military installations. A total of 55 of the 108 Iraqi vessels destroyed during the conflict were targeted by P-3C aircraft.[23]

The P-3 Orion's mission expanded in the late 1990s and early 2000s to include battlespace surveillance both at sea and over land. The long range and long loiter time of the P-3 Orion have proved to be an invaluable asset during Operation Iraqi Freedom and Operation Enduring Freedom. It can instantaneously provide information about the battlespace it can see to ground troops, particularly the U.S. Marines.

In Afghanistan

Although the P-3 is a Maritime Patrol Aircraft, armament and sensor upgrades in the Anti-surface Warfare Improvement Program (AIP)[24] have made it suitable for sustained combat air support over land.[24] In what became known as the "Decade in the Desert", Navy P-3C crews patrolled combat zones in the middle east and southwest Asia.[25] Since the start of the current war in Afghanistan, U.S. Navy P-3 aircraft have been operating from Kandahar in that role.[26] Royal Australian Air Force AP-3C Orions operated out of Minhad Air Base in the UAE from 2003 until their withdrawal in November 2012. During the period 2008–2012, the AP-3C Orions conducted overland intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance tasks in support of coalition troops throughout Afghanistan.[27]

The United States Geological Survey used the Orion to survey parts of southern and eastern Afghanistan for lithium, copper, and other mineral deposits.[28]

In Libya

Several U.S. Navy P-3C Orions, and two Canadian CP-140 Auroras, a variant of the Orion, have participated in maritime surveillance missions over Libyan waters in the framework of enforcement of the 2011 no-fly zone over Libya.[29][30]

A U.S. Navy P-3C Orion supporting Operation Odyssey Dawn engaged the Libyan coast guard vessel Vittoria on 28 March 2011 after the vessel and eight smaller craft fired on merchant ships in the port of Misrata, Libya. The Orion fired AGM-65 Maverick missiles on Vittoria, which was subsequently beached.[31]

Iran

Lockheed produced the P-3F variant of the P-3 Orion, for Iran. Six examples were delivered to the former Imperial Iranian Air Force (IIAF) in 1975 and 1976.

Following the Iranian Revolution in 1979, the Orions continued in service, after the IIAF was renamed the Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force (IRIAF). They were used in the Tanker War phase of the Iran–Iraq War and were operated by one of the most successful squadrons of the IRIAF during that conflict. A total of four P-3Fs remain in service.

Pakistan

Three P-3C Orions, delivered to the Pakistan Navy in 1996 and 1997 were operated extensively during the Kargil conflict. After the crash of one, the type was grounded due to the loss of an entire crew; nonetheless, the aircraft were maintained in an armed state and airworthy condition throughout the escalation period of 2001 and 2002. In 2007, they were used by the navy to conduct signals intelligence, airborne and bombing operations in a Swat offensive and Operation Rah-e-Nijat. Precision and strategic bombing missions were carried out by the Orions, and in 2007, intelligence management operations were conducted against Taliban and al-Qaeda operatives.[32]

On 22 May 2011, two out of the four Pakistani P-3Cs were destroyed in an attack on PNS Mehran, a Pakistani Naval station in Karachi.[33] The Pakistani fleet had been readily used in overland, counter-insurgency operations. In June 2011, the U.S. agreed to replace the destroyed aircraft with two new ones, with delivery to follow later.[34] In February 2012, the U.S. delivered two additional P-3C Orion aircraft to the Pakistan Navy.[35]

In Somalia

The Spanish Air Force deployed P-3s to assist the international effort against piracy in Somalia. On 29 October 2008, a Spanish P-3 aircraft patrolling the coast of Somalia reacted to a distress call from an oil tanker in the Gulf of Aden. To deter the pirates, the aircraft flew over the pirates three times as they attempted to board the tanker, dropping a smoke bomb on each pass. After the third pass, the attacking pirate boats broke off their attack.[36] Later, on 29 March 2009, the same P-3 pursued the assailants of the German navy tanker Spessart (A1442), resulting in the capture of the pirates.[37]

In April 2011, the Portuguese Air Force also contributed to Operation Ocean Shield by sending a P-3C[38] which had early success when on its fifth mission detected a pirate whaler with two attack skiffs.[39]

Since 2009 the Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force has deployed P-3s to Djibouti for anti-piracy patrols,[40][41][42] from 2011 from its own base.[43] As well the German Navy is contributing assets against piracy with one P-3 from time to time.

Civilian uses

Several P-3 aircraft have been N-registered and are operated by civilian agencies. The US Customs and Border Protection has a number of P-3A and P-3B aircraft that are used for aircraft intercept and maritime patrol. NOAA operates two WP-3D variants specially modified for hurricane research. One P-3B, N426NA, is used by National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) as an Earth science research platform, primarily for the NASA Science Mission Directorate's Airborne Science Program. It is based at Goddard Space Flight Center's Wallops Flight Facility, Virginia.

Aero Union, Inc. operated eight secondhand P-3A aircraft configured as air tankers, which were leased to the U.S. Forest Service, the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection and other agencies for firefighting use. Several of these aircraft were involved in the U.S. Forest Service airtanker scandal but have not been involved in any catastrophic aircraft mishaps. Aero Union has since gone bankrupt, and their P-3s have been put up for auction.[44]

Variants

Over the years, numerous variants of the P-3 have been created. A few notable examples are:

- WP-3D: Two P-3C aircraft as modified on the production line for NOAA weather research, including hurricane hunting.

- EP-3E Aries: 10 P-3A and 2 EP-3B aircraft converted into ELINT aircraft.

- EP-3E Aries II: 12 P-3C aircraft converted into ELINT aircraft.

- AP-3C: Royal Australian Air Force P-3C/W aircraft which have been extensively upgraded by L-3 Communications with new mission systems, including an Elta SAR/ISAR radar and a General Dynamics Canada acoustic processor system.

- CP-140M Aurora: Long-range maritime reconnaissance, anti-submarine warfare (ASW) aircraft for the Canadian Forces. Based on the P-3C Orion airframe, but mounts the more advanced electronics suite of the Lockheed S-3 Viking; 18 built

- CP-140A Arcturus: Three P-3s without ASW equipment for CP-140 Aurora crew training and various coastal patrol missions.

- P-7 proposed new-build and improved variant as a P-3 Orion replacement later canceled.

- Orion 21 proposed new-build and improved variant as a P-3 Orion replacement; lost to the Boeing P-8 Poseidon.

- P-3K2: Royal New Zealand Air Force P-3K2 aircraft which have been fully upgraded with totally new mission systems by L-3 Mission Integration Division, Greenville, Texas

. The flight deck now has 'glass' instrumentation and navigation computer automation. The Tactical Rail (Tacrail) has been completely refitted with modern sensors, communication and data management systems.

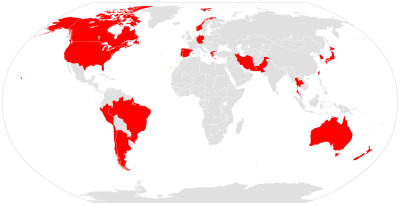

Operators

Military operators

- Argentine Naval Aviation – six P-3B; based at Base Aeronaval Alte. Zar, Trelew

- Royal Australian Air Force – 18 AP-3C, 1 P-3C

- No. 92 Wing

- 10 Sqn, 11 Sqn and No. 292 Sqn; based at RAAF Base Edinburgh

- No. 92 Wing

In 2002, the RAAF received significantly upgraded AP-3C. Also known as Australian Orions they are fitted with a variety of sensors. They include digital multi-mode radar, electronic support measures, electro-optics detectors (infrared and visual), magnetic anomaly detectors, identification friend or foe systems, and acoustic detectors.[45] The Boeing P-8 Poseidon is gradually replacing them. The P-3 Orion celebrated 50 years of RAAF service in November 2018. P-3B sold to Portugal.

- Brazilian Air Force – 9 P-3AM (Upgraded) in 2008 (12 ex-USN airframes purchased).[46] Integrated with the CASA FITS (Fully Integrated Tactical System)utilized in antisubmarine warfare.

- Chilean Navy – four P-3A; based at Base Aeronaval Torquemada, Concón. Three used as patrol aircraft, one used for personnel transport. Chile plans to extend their service lives past 2030 by changing the wings, modernizing the engines, and integrating the AGM-84 Harpoon anti-ship missile.[47]

- Royal Canadian Air Force – Canada purchased 18 P-3A in 1980. The CP-140 Aurora are operated by 404 Long Range Patrol and Training Squadron, 405 Long Range Patrol Squadron, 415 Long Range Patrol Force Development Squadron, (all three from 14 Wing Greenwood), 407 Long Range Patrol Squadron (19 Wing Comox).[48][49]

- The RCAF also operated 3 CP-140A Arcturus, P-3 aircraft purchased in 1991 without an anti-submarine warfare suite and used primarily for pilot training and long-range surface patrol. The last two were retired in 2011.

- German Navy – eight P-3C CUP+ (ex Royal Netherlands Navy); based at NAS Nordholz, Marinefliegergeschwader 3 Graf Zeppelin

- Hellenic Air Force – six P-3B operated jointly with the Hellenic Navy, 1 in operable condition as of 2019, 3 additional of the planes are undergoing maintenance as of 2016 which should return them to airworthy condition, the first of which was completed in May 2019.[50]

- Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force – four P-3F (71ASW SQN); based at Shiraz International Airport (Shahid Douran Air Base)

- Japan Maritime Self-Defense Force – 93 P-3C, five EP-3, five OP-3C, one UP-3C, three UP-3D.[51] The Kawasaki Corporation assembled five airframes produced by Lockheed, and then Kawasaki produced more than 100 P-3s under license in Japan.[52] The Kawasaki P-1 is gradually replacing them.

- Air Patrol Squadron 3 (JMSDF) (1984–2017)[53]

- Royal New Zealand Air Force – six P-3K2 (5 Sqn); based in RNZAF Base Auckland. Operated by 5 SQN. Five were originally delivered in 1966 as P-3Bs. Another was purchased from the RAAF in 1985. All six have been upgraded by L-3 Communications Canada and now designated as P-3K2,[54] with the first upgraded aircraft delivered back to New Zealand in April 2011.[55] The New Zealand Government announced[56] they are to be replaced in 2023 with the purchase of 4 Boeing P-8A Poseidons. An interim upgrade contract worth NZ$36M has been awarded to Boeing to upgrade the underwater intelligence, reconnaissance and surveillance capability of the P-3K2,[57] with a capability similar to what is provided in the P-8.[58]

- Royal Norwegian Air Force – four P-3C, two P-3N (333 Sqn); based in Andøya Air Station

- Pakistan Naval Air Arm – ~Four P-3C; based in Naval aviation base Faisal, Karachi. Upgraded P-3C MPA and P-3B AEW models (equipped with Hawkeye 2000 AEW system) ordered in 2006,[59] first upgraded P-3C delivered in early 2007. In June 2010, two more upgraded P-3Cs joined the Pakistan Navy with anti-ship and submarine warfare capabilities. A total of nine (9).[60] Two aircraft were destroyed in an attack by armed militants at the Mehran Naval Airbase.

- Portuguese Air Force – five P-3C CUP+ (ex Royal Netherlands Navy) operated by 601 Squadron "Lobos", based in Beja Air Base. They replaced six former RAAF P-3Bs upgraded to P-3Ps in the late 1980s. The last P-3P flew on 13 October 2011.

- Republic of Korea Navy – eight P-3Cs, eight P-3CKs; based in Pohang Airport and Jeju international airport. Korean Air/L-3 Communications are upgrading the P-3C aircraft with new electronics, including new magnetic anomaly detectors, electro-optical sensors, surveillance equipment and a self-protection suite. The Navy's impetus stems from a 2010 experience in which ROK forces detected only 28% of North Korean submarines involved in exercises.[61]

- Spanish Air Force – Two P-3A HWs, four P-3B ( ex-Norway) being upgraded to P-3M, based at Morón Air Base. The Spanish AF bought five P-3B from Norway in 1989 and it was planned to upgrade all five to M standard, however, due to budgetary constraints only four are to be upgraded, the remaining aircraft being used as spares source.

- Republic of China Air Force(1966–1967) – Least known of all P-3 family. Three P-3As (149669, 149673, 149678) were obtained by the CIA from the U.S. Navy under Project STSPIN in May 1963, as the replacement aircraft for CIA's own covert operation fleet of RB-69A/P2V-7U versions. Converted by Aerosystems Division of LTV at Greenville, Texas, the three P-3As were simply known as "black" P-3As under "Project Axial". Officially transferred from U.S. Navy to CIA on June/July 1964, LTV Aerosystems converted the three aircraft to be both ELINT and COMINT platform. First of three "black" P-3As arrived in Taiwan and officially transferred to ROCAF's top secret Black Bat Squadron on 22 June 1966. Armed with four Sidewinder short range AAM missiles for self-defense, the three "black" P-3A flew peripheral missions along the China coast to collect SIGINT and air samples. When the project was terminated in January 1967, all three "black" P-3As were flown to NAS Alameda, CA, for long term storage. In September 1967, Lockheed at Burbank, converted two of the three aircraft (149669 and 149678) into the only two EP-3B examples in existence in the world, while the third aircraft (149673) was converted by Lockheed in 1969–1970 to serve as a development aircraft for various electronic programs. The two EP-3Bs known as "Bat Rack", owing to their short period of service with Taiwan's "Black Bat" Squadron, were issued to U.S. Navy's VQ-1 Squadron in 1969 and deployed to Da Nang, Vietnam. Later, the two EP-3Bs were converted to EP-3E ARIES, along with seven EP-3As. The two EP-3Es retired in the 1980s, when replaced by 12 EP-3E ARIES II versions.[62]

- Republic of China Navy – The Taiwan Navy obtained 12 P-3C aircraft under the U.S. government's Foreign Military Sales program in 2007 which were then modernized to provide an additional 15,000 flight hours.[63] 12 P-3Cs (Ordered, with deliveries starting in 2012), with three "spare" airframes that might be converting to EP-3E standard; based in south part of the island and offshore island.[64] In May 2014 Lockheed Martin were awarded a contract to upgrade and overhaul all 12 P-3Cs for completion by August 2015.[65]

- United States Navy – 100 P-3Cs and 14 EP-3Es in service.[66] The government of Singapore has expressed an interest in buying surplus P-3C aircraft from the U.S. Navy.[67]

Former military operators

- Royal Netherlands Navy – Netherlands Naval Aviation Service – former operator. Sold to Portugal and Germany.

- Royal Thai Navy – two P-3Ts, one VP-3T, one UP-3T ; based at RTNAB U-Tapao (102 Sqn). Whithdrawn from active service in 2014.

Civilian operators

United States

- National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) – two WP-3Ds flown by NOAA Commissioned Corps officers, previously based at MacDill AFB, now based at Lakeland Linder International Airport, Florida

- National Aeronautics and Space Administration – one ex-USN P-3B; based at NASA's Wallops Flight Facility, Virginia used for low altitude heavy lift airborne science missions, modified to support passive microwave instruments, such as NOAA's Polarimetric Scanning Radiometer (PSR), NASA's 2-DSTAR, and the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) polarimetric scatterometer (POLSCAT) instruments.[68]

- United States Department of Homeland Security / Bureau of Customs and Border Protection / Office of Air and Marine – eight P-3 AEWs; based at NAS Corpus Christi, Texas and Cecil Field and NAS Jacksonville, Florida. Used for border patrol and anti-drug duties. Former USN aircraft, modified and equipped with the same Airborne Early Warning radar as fitted to the E-2 Hawkeye.[69]

- United States Department of Homeland Security / Bureau of Customs and Border Protection / Office of Air and Marine – 8 P-3 LRTs (Long Range Tracker). Former USN aircraft also based at NAS Corpus Christi, Texas and Cecil Field, Jacksonville, Florida. Normally operate in tandem with P-3 AEW aircraft.[70]

- MHD-ROCKLAND Services, Inc. - 5 former RAAF AP-3Cs. Aircraft are FAA Registered as L285D, and based in Keystone Heights, FL.

- Airstrike Firefighters – 1 former Aero Union Tanker 23, with plans for 6 more P-3's.[72]

Former Civilian Operators

United States

- Aero Union – eight ex-USN P-3A; aircraft based at Chico Municipal Airport in Chico, California and converted into aerial firefighting platforms[73] Aero Union shut down and put its Orions up for auction in 2011.[44]

Notable events, accidents, and incidents

- 30 January 1963: United States Navy P-3A BuNo 149762 was lost at sea in the Atlantic Ocean, 14 crew killed.[74]

- 4 July 1966: Lockheed P-3A Orion, BuNo 152172, construction number 185-5142, assigned to VP-19, Radio call sign Papa Echo Zero Five (PE-05), crashed 7 miles (11 km) northeast Battle Creek, MI. The P-3A Orion was on the return leg of a cross country training flight from NAS New York-Floyd Bennett Field, New York to NAS Moffett Field, California via NAS Glenview, Illinois; all four crew lost.[75]

- 6 Feb 1968: Lockheed P-3B Orion, Registration 153440, construction number 185-5237, assigned to VP-26, crashed during an Operation Market Time combat patrol off Phu Quoc Island, Vietnam, with the loss of all 12 crew MIA. Initially attributed to mechanical failure, later events suggest it may have been shot down.[76]

- 1 Apr 1968: Lockheed P-3B Orion, Registration 153445, construction number 185-5241, assigned to VP-26, was shot down by surface anti-aircraft fire during an Operation Market Time combat patrol off PhuQ uoc Island, Vietnam. The AAA fire initially set an engine on fire, but during a subsequent attempt to land, the wing separated and the aircraft crashed, with the loss of all 12 crew.[77]

- 11 Apr 1968: Lockheed P-3B Orion, Registration A9-296, construction number 185-5406, assigned to RAAF, , crashed on runway 32L at NAS Moffett Field, California after departing the manufacturer's facility during pre-delivery acceptance trials. The left main mount (undercarriage) collapsed on landing and the aircraft ground-looped. All crew survived without serious injury, but the aircraft was completely destroyed by the resulting fire.[78]

- 6 March 1969: USN P-3A BuNo 152765 tail coded RP-07 of VP-31 crashed at NAS Lemoore, California, at the end of a practice ground control approach (GCA) landing, all six crew died.

- 28 January 1971: Commander Donald H. Lilienthal, USN flew a P-3C Orion to a world speed record for heavyweight turboprops. Over 15–25 kilometers, he reached 501 miles per hour to break the Soviet Il-18's May 1968 record of 452 miles per hour.

- 26 May 1972: USN P-3A BuNo 152155 disappeared over the Pacific Ocean on a routine training mission after departing NAS Moffett Field, California, with the loss of eight crew members.[79]

- 3 June 1972: While attempting to fly through the Straits of Gibraltar, en route from Naval Station Rota, Spain to Naval Air Station Sigonella, Sicily, a U.S. Navy P-3A of VP-44 hit a mountain in Morocco, resulting in the death of all 14 crew on board the aircraft.[80]

- 12 April 1973: A United States Navy P-3C BuNo 157332 operating from NAS Moffett Field, California collided with a Convair CV-990 (N711NA) operated by NASA during approach to runway 32L. The aircraft crashed on the Sunnyvale Municipal Golf Course, 0.5 miles (0.80 km) short of the runway, resulting in destruction of both aircraft and the death of all but one crewmember.[81]

- 11 December 1977: USN P-3B BuNo 153428 from VP-11 operating from Lajes Field, Azores crashed on mountainous El Hierro (southwesternmost of the Canary Islands) in poor visibility. There were no survivors from the crew of 13.[82]

- 26 April 1978: USN P-3B BuNo 152724 from VP-23 crashed on landing approach to Lajes Field, Azores. Seven of the crew were killed and the plane sank into deep water preventing recovery to assess the cause of the crash.[83]

- 22 September 1978: USN P-3B BuNo 152757 from VP-8 disintegrated over Poland, Maine on 22 September 1978. An over-pressurized fuel tank caused the port wing to separate at the outboard engine.[84] The detached wing sheared off part of the tail; and aerodynamic forces caused the remaining engines and starboard wing to detach from the fuselage. Debris rained down near the south end of Tripp Pond shortly after 12:00. There were no survivors from the plane's 8-man crew.[85]

- 26 October 1978: USN P-3C BuNo 159892 call sign coded AF 586 from VP-9 operating from NAS Adak ditched at sea after an engine fire caused by a propeller malfunction. All but two of the 15-man crew were rescued by a Soviet trawler, but three crew members died of exposure.[86]

- 27 June 1979: P-3B BuNo 154596 from VP-22 operating from NAS Cubi Point Philippines, had a propeller overspeed shortly after departure. The number 4 propeller then departed the aircraft striking the number three with a subsequent fire on that engine. While attempting an overweight landing with 2 engines out, the aircraft stalled, rolled inverted and crashed in Subic Bay just past Grande Island. Four crew and one passenger were killed in the crash.[87]

- 17 April 1980: USN P-3C BuNo 158213 from VP-50 while flying for a parachuting exhibition in Pago Pago, American Samoa struck overhead tram wires and crashed, killing all six crew on board.[87]

- 17 May 1983: USN P-3B BuNo 152733 tail coded YB-07 from VP-1 inadvertently landed gear up during a routine dedicated field work (DFW) pilot training flight at NAS Barbers Point. No crew were injured but the aircraft was a total loss.[88]

- 16 June 1983: USN P-3B BuNo 152720 tail coded YB-06 from VP-1 at NAS Barbers Point crashed into a mountain top in fog and low clouds on the Napali Coast between the Hanapu and Kalalau valleys in Kauai, Hawai'i shortly after 0400 hours, killing all 14 on board.[87][89]

- 13 September 1987: A Royal Norwegian Air Force P-3B, tail number "602", is hit from below by a Russian Air Force Sukhoi Su-27 of the 941st IAP V-PVO. The Su-27 flew below the P-3's starboard side, then accelerated and pulled up, clipping the #4 engine's propellers. The propeller shrapnel hit the Orion's fuselage and caused a decompression. There were no injuries and both aircraft returned safely to base.[90]

- 25 September 1990: The first production model P-3C Update III, BuNo 161762, assigned to VP-31 at NAS Moffett Field, impacted the runway at an excessive rate of descent while conducting at dedicated field work sortie at Naval Auxiliary Landing Field Crows Landing. Both main landing gear failed and the aircraft slid down the runway. Some crewmembers sustained minor injuries, but there were no fatalities. The aircraft was a total loss.[91]

- 21 March 1991: While on a training mission west of San Diego, California, two U.S. Navy P-3C Orions, BuNos 158930 and 159325 assigned to VP-50 based at NAS Moffett Field collided in midair, killing all 27 crew on board both aircraft.[92]

- 26 April 1991: AP-3C, tail number A9-754 of the Royal Australian Air Force, lost a wing leading edge and crashed into shallow water in the Cocos Island; one crewman was killed. Aircraft was cut up and used as an artificial reef.[93] The head investigator of this incident was RAAF FLTLT Richard Hall.[94]

- 16 October 1991: P-3A N924AU of Aero Union crashed into a mountain in Montana, United States killing both crew.[95]

- 25 March 1995: USN P-3C BuNo 158217 assigned to VP-47 was returning from a training mission in the North Arabian Sea when it suffered catastrophic engine failure of the number 4 engine. The aircraft ditched at sea 2 miles (3.2 km) from RAFO Masirah, Oman. All 11 crew members were rescued by the Royal Omani Air Force.[96]

- 1 April 2001: An aerial collision known as the Hainan Island incident between a USN EP-3E ARIES II, BuNo 156511, a signals reconnaissance version of the P-3C, and a People's Liberation Army Navy J-8IIM fighter resulted in the J-8IIM crashing and its pilot was killed. The EP-3 came close to becoming uncontrollable, at one point sustaining a near inverted roll, but was able to make an emergency landing on Hainan.[97]

- 20 April 2005: P-3B N926AU of Aero Union crashed while conducting practice drops of water over an area of rugged mountainous terrain located north of the Chico Airport. All three crew onboard were killed.[98]

- 22 May 2011: Twenty Tehrik-i-Taliban Pakistan militants claiming to avenge Osama Bin Laden's death destroyed two Pakistan Navy P-3C Orions during an armed attack at PNS Mehran, a heavily guarded base of the Pakistan Navy located in Karachi.[99] The aircraft had been readily used by the Pakistani military in overland counter-insurgency surveillance operations.[100]

- 15 February 2014: Three US Navy P-3C Orions were crushed "beyond repair" when their hangar, at NAF Atsugi, Japan was destroyed due to a massive snow storm.[101][102]

Surviving aircraft

- 150509 – P-3A – Moffett Field Historical Society (former NAS Moffett Field), California.

- 151370 – P–3A Cockpit – Moffett Field Historical Society (former NAS Moffett Field), California.

- 150511 – VP-3A – Pima Air and Space Museum, adjacent to Davis-Monthan AFB, Tucson, Arizona. Aircraft last assigned to Executive Transport Det, NAS Signonella, Sicily

- 151374 – P-3A – NAS Jacksonville Heritage Park, NAS Jacksonville, Florida

- 152152 – P-3A – National Naval Aviation Museum, NAS Pensacola, Florida. Aircraft last assigned to VP-69.

- 152156 – P-3A – Brunswick Executive Airport (former NAS Brunswick), Maine

- 152184 – VP-3T – U-Tapao RTAFB, Thailand. Former US Navy aircraft, transferred to, operated by and later retired as gate guard by Royal Thai Navy.

- 152729 – P-3B – U.S. Customs and Border Protection, Washington, DC. Registered as N769SK.

- 152748 – P-3B – Navy Operational Support Center (formerly Naval Air Facility Detroit), Selfridge ANGB, Michigan. Aircraft last assigned to VP-93.

- 160770 – P-3C CDU – Naval Air Museum Barbers Point, Kalaeloa Airport (former Naval Air Station Barbers Point), Hawaii. Aircraft last assigned to VP-9, but carrying 1960s era markings of VP-6 for U.S. Naval Aviation Centennial celebration in 2011.

- 156515 – P-3C Hickory Aviation Museum, at Hickory Regional Airport, Hickory North Carolina.

- 160753 – AP-3C – Historical Aircraft Restoration Society, Shellharbour Airport, New South Wales, Australia. Ex-Royal Australian Air Force A9-753, former 10 Squadron aircraft and later 292 Squadron as a static training aid.[103] Officially handed over to HARS by the RAAF on 3 November 2017.[104] Civil registered as VH-ORI and will be maintained as a flying warbird.[105]

- 160756 – AP-3C – South Australian Aviation Museum, South Australia. Construction number 5666, RAAF A9-756, received by 10 Squadron as a P-3C in 1978, upgraded to AP-3C in early 2000s.[106]

- 160999 – P-3C UD II – Marine Corps Air Station Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii. Aircraft last assigned to VP-9.

- 161006 – P-3C UD II – Joint Base Andrews (former Naval Air Facility Washington), Maryland. Aircraft last assigned to VP-68.

- RCAF Serial 140119 – CP-140A – Greenwood Military Museum, CFB Greenwood, Canada. Aircraft last assigned to RCAF 404 (MP) Squadron.

Specifications (P-3C Orion)

Data from Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1994-95,[107] Specifications: P-3,[108]

General characteristics

- Crew: 11

- Length: 116 ft 10 in (35.61 m)

- Wingspan: 99 ft 8 in (30.38 m)

- Height: 33 ft 8.5 in (10.274 m)

- Aspect ratio: 7.5

- Airfoil: root: NACA 0014 modified; tip: NACA 0012 modified[109]

- Empty weight: 61,491 lb (27,892 kg)

- Zero-fuel weight: 77,200 lb (35,017 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 135,000 lb (61,235 kg) MTOW normal

- 142,000 lb (64,410 kg) maximum permissible

- Maximum landing weight: (MLW) 103,880 lb (47,119 kg)

- Fuel capacity: 9,200 US gal (7,700 imp gal; 35,000 l) usable fuel in 5 wing and fuselage tanks ; (62,500 lb (28,350 kg) maximum fuel weight) ; 111 US gal (92 imp gal; 420 l) usable oil in 4 tanks

- Powerplant: 4 × Allison T56-A-14 turboprop engines, 4,910 shp (3,660 kW) each (equivalent)

- Propellers: 4-bladed Hamilton Standard 54H60-77, 13 ft 6 in (4.11 m) diameter constant-speed fully-feathering reversible propellers

Performance

- Maximum speed: 411 kn (473 mph, 761 km/h) at 15,000 ft (4,572 m) and 105,000 lb (47,627 kg)

- Cruise speed: 328 kn (377 mph, 607 km/h) at 25,000 ft (7,620 m) and 110,000 lb (49,895 kg)

- Patrol speed: 206 kn (237 mph; 382 km/h) at 1,500 ft (457 m) and 110,000 lb (49,895 kg)

- Stall speed: 133 kn (153 mph, 246 km/h) flaps up

- 112 kn (129 mph; 207 km/h) flaps down

- Combat range: 1,345 nmi (1,548 mi, 2,491 km) (3 hours on station at 1,500 ft (457 m))

- Ferry range: 4,830 nmi (5,560 mi, 8,950 km)

- Endurance: 17 hours 12 minutes at 15,000 ft (4,572 m) on two engines

- 12 hours 20 minutes at 15,000 ft (4,572 m) on four engines

- Service ceiling: 28,300 ft (8,600 m)

- 19,000 ft (5,791 m) one engine inoperative (OEI)

- Rate of climb: 1,950 ft/min (9.9 m/s)

- Time to altitude: 25,000 ft (7,620 m) in 30 minutes

- Wing loading: 103.8 lb/sq ft (507 kg/m2)

- Power/mass: 0.1455 lb/hp (0.0885 kg/kW) (equivalent)

- Take-off run: 4,240 ft (1,292 m)

- Take-off distance to 50 ft (15 m): 5,490 ft (1,673 m)

- Landing distance from 50 ft (15 m): 2,770 ft (844 m)

Armament

- Hardpoints: 10 wing stations in total (3x on each wing and 2x on each wing root) and eight internal bomb bay stations with a capacity of 20,000 lb (9,100 kg),with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Rockets: None

- Missiles:

- Air-to-surface missile:4× AGM-65 Maverick,6× AGM-84 Harpoon,4× AGM-84 Standoff Land Attack Missile (SLAM-ER)

- Bombs:

- Depth charges, Mk 101 Lulu nuclear depth bomb,10× MK20 Rockeye, MK80 Series (18× MK82, MK83, MK84) general-purpose bombs, B57 nuclear bomb (US service only, retired 1993)

- Other:

- Mk 44 (mostly retired from service),8× Mk 46, 6× Mk 50,7× Mk 54 or MU90 Impact torpedoes

- Mk 25, Mk 39, Mk 55,7× Mk 56, Mk 60 CAPTOR or 6× Mk 65 or 18× mk 62 or 11×mk 63 Quickstrike naval mines[110]

- Stonefish naval mine (in Australian service)

- Active and passive Sonobuoys

Avionics

- RADAR: Raytheon AN/APS-115 Maritime Surveillance Radar, AN/APS-137D(V)5 Inverse Synthetic Aperture Search Radar[110]

- IFF: APX-72, APX-76, APX-118/123 Interrogation Friend or Foe (IFF)[110]

- EO/IR: ASX-4 Advanced Imaging Multispectral Sensor (AIMS), ASX-6 Multi-Mode Imaging System (MMIS)

- ESM: ALR-66 Radar Warning Receiver, ALR-95(V)2 Specific Emitter Identification/Threat Warning

- Hazeltine Corporation AN/ARR-78(V) sonobuoy receiving system[110]

- Fighting Electronics Inc AN/ARR-72 sonobuoy receiver[110]

- IBM Proteus UYS-1 acoustic processor

- AQA-7 directional acoustic frequency analysis and recording sonobuoy indicators[110]

- AQH-4 (V) sonar tape recorder[110]

- ASQ-81 magnetic anomaly detector (MAD)[110]

- ASA-65 magnetic compensator[110]

- Lockheed Martin AN/ALQ-78(V) electronic surveillance receiver[110]

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Avro Shackleton

- Boeing P-8 Poseidon

- Bombardier Aerospace DHC-8-MPA-D8

- Breguet Atlantique

- Canadair CP-107 Argus

- CASA CN-235 MPA

- CASA C-295 MPA

- EADS HC-144 Ocean Sentry

- Hawker-Siddeley Nimrod

- Ilyushin Il-38

- Kawasaki P-1

- Shin Meiwa PS-1

Related lists

References

- "Lockheed Martin P-3 Orion." Archived 11 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Aeroflight.co.uk, 31 July 2010. Retrieved: 16 November 2010.

- "P-3 production." Archived 1 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine p3orion.nl. Retrieved: 7 June 2011.

- "P-3 history." Archived 24 March 2010 at the Wayback Machine GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- Reade 1998.

- "Second VP-9." Archived 27 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine Dictionary of American Naval Aviation Squadrons — Volume 2, p. 74. Retrieved: 7 July 2012.

- Thomas, Todd J. "First Digital Airborne Computing System: UNIVAC 1830, CP-823/U Serial A-New Mod 3, Engineering Prototype Lockheed P-3 Orion." Archived 15 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine p3oriontopsecret.com, 2010. Retrieved: 9 December 2010.

- Serling, Robert J., Loud and Clear, Dell, 1970.

- Lessons of a turboprop inquest Archived 4 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Flight 17 February 1961 p.225

- Murphy, Pat. "Fighting fire like a regular military ground, air war: Onetime jinxed airliner now a superstar fire bomber." mtexpress.com, 2010. Retrieved: 16 November 2010.

- "P-3 Orion Overview." Archived 23 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Federation of American Scientists (FAS). Retrieved: 25 January 2011.

- Barbour, John (14 July 1990). "Retooling the war machine". Idahonian. (Moscow). Associated Press. p. 6C.

- "Lockheed Martin Awarded Contract to Build Outer Wing Sets for the US Navy's P-3 Orion Fleet." Archived 18 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine deagel.com, 4 September 2008.

- "P-3C." Archived 28 July 2010 at the Wayback Machine history.navy.mil. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- "Air Anti-Submarine Warfare ." Archived 12 January 2010 at the Wayback Machine fas.org. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- Holler, Roger A. (5 November 2013). "The Evolution Of The Sonobuoy From World War II To The Cold War" (PDF). U.S. Navy Journal of Underwater Acoustics: 332–333. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- Whitman, Edward C. (Winter 2005). "SOSUS The "Secret Weapon" of Undersea Surveillance". Undersea Warfare. Vol. 7 no. 2. Retrieved 24 March 2020.

- "'Born to Fly,' by Lt. Shane Osborn: Navy Lt. Shane Osborn's Tale of Danger and Survival." Archived 29 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine abcnews.go.com, 30 September 2004. Retrieved: 28 July 2010.

- "P-3 Subhunters Using ASW Gear to Find Narco-Subs?" Archived 19 January 2011 at the Wayback Machine defensetech.org, 14 January 2011. Retrieved: 25 January 2011.

- Page, Lewis. "First true submarine captured from American drug smugglers." Archived 5 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine The Register, 6 July 2010. Retrieved: 25 January 2011.

- Fair winds and following seas to the Navy’s P-3C. Navy Times. 4 June 2020.

- "VP-26 Memorial: VP-26 Crew – In Memorium – VP-26 Crew." Archived 10 May 2007 at the Wayback Machine vpnavy.org. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- Reade 1998, pp. 42–49.

- Chudy, Jason. "P-3C Anti-Surface Warfare Improvement Program (P-3C AIP)." Archived 29 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine lockheedmartin.com. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- Rogoway, Tyler (2 July 2014). "Confessions Of A US Navy P-3 Orion Maritime Patrol Pilot". Foxtrot Alpha. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- Chudy, Jason."P-3C Anti-Surface Warfare Improvement Program (P-3C AIP)." Archived 11 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine military.com. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- "Defence Ministers » Minister for Defence and Minister for Defence Science and Personnel – Joint Media Release – Last AP-3C Orion Aircraft welcomed home from Middle East". defence.gov.au. Archived from the original on 29 April 2013.

- Risen, James. "U.S. Identifies Vast Mineral Riches in Afghanistan." Archived 15 December 2014 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 13 June 2010. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- "British ships protected by borrowed US spy plane in Libya." Archived 11 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine The Telegraph. Retrieved: 7 January 2012.

- Strelieff, Captain Jill. "Auroras fly first missions over Libya." Archived 12 December 2011 at the Wayback Machine Sicily Air Wing Public Affairs, 4 October 2011. Retrieved: 7 January 2012.

- "US Navy P-3C, USAF A-10 and USS Barry Engage Libyan Vessels." Archived 20 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine africom.mil, 29 March 2011. Retrieved: 29 March 2011

- Mackey, Robert. "Before Attack, Pakistan’s Navy Boasted of Role in Fight Against Taliban." Archived 17 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 23 May 2011. Retrieved: 10 April 2012.

- "Foreign Hand Behind PNS Mehran Base Attack in Pakistan". Pakalert Press. 26 May 2011. Archived from the original on 29 May 2011.

- "US to replace two P3C Orion aircraft." Archived 2 September 2011 at the Wayback Machine Dawn.com, 17 June 2011.

- "Pakistan Navy receives two P3Cs." Archived 19 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine News International, 22 February 2012. Retrieved: 9 April 2012.

- "Spain foils pirates' plans." Archived 1 November 2008 at the Wayback Machine news24.com. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- "Boxer Supports International Counter-Piracy Effort in Gulf of Aden – Other Attacks Increase Off Somali Coast." Archived 16 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine dvidshub.net, 28 October 2008. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- "P-3 na Operação 'Ocean Shield'." Archived 5 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine Força Aérea Portuguesa, 5 April 2011. Retrieved: 28 June 2011.

- "News Release: NATO’S latest counter piracy weapon strikes early blow." Allied Maritime Command Headquarters Northwood, 29 April 2011. Retrieved: 28 June 2011.

- Japan: Joining the Anti-Piracy Effort off the Somali Coast May 28, 2009 Retrieved 21 November 2016

- Here’s how Coalition Patrol Planes Hunt Somali Pirates in the Horn of Africa January 23, 2013 Archived 2 February 2017 at the Wayback Machine The Aviationist Retrieved 21 November 2016

- Japan's Actions against Piracy off the Coast of Somalia February 15, 2016 Archived 9 December 2016 at the Wayback Machine Ministry of Foreign Affairs Retrieved 21 November 2016

- Japan to expand Djibouti military base to counter Chinese influence October 13, 2016 Archived 19 May 2017 at the Wayback Machine Reuters Retrieved 21 November 2016

- "Aero Union to auction their P-3 air tankers". wildfiretoday.com. Archived from the original on 14 September 2012. Retrieved 8 May 2013.

- "AP-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft". raaf.gov. 29 March 2009. Archived from the original on 19 December 2008. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- "World Air Forces listing A-B". 24 November 1999. Archived from the original on 21 November 2016. Retrieved 20 February 2016.

- "Chile; P-3 Orions life extension plans". Dmilt.com. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 13 July 2013.

- Green, William (1988). Aircraft (37 ed.). Frederick Warne. pp. 142–143. ISBN 0 7232 3534 1.

- "CP-140 Aurora". Royal Canadian Air Force. Archived from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- Igor, Bozinovski (21 May 2019). "Greek P-3B re-enters service". Jane's 360. Skopje. Archived from the original on 21 May 2019. Retrieved 21 May 2019.

- Polmar, Norman (2005). The Naval Institute guide to the ships and aircraft of the U.S. fleet (18th ed.). Annapolis, Maryland, USA: Naval Institute. p. 416. ISBN 1-59114-685-2.

- 厚木航空基地HP トピックス:P-1への移行完了 Archived 30 September 2017 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 September 2017 (in Japanese)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "New Zealand to buy four P-8A Poseidon Maritime Patrol Aircraft". The Beehive. Archived from the original on 10 July 2018. Retrieved 9 July 2018.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 12 January 2019. Retrieved 11 January 2019.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Ansari, Usman. "Pakistan Navy To Boost Air Surveillance Capability." defencenews.com, 30 January 2010. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- Ansari, Usman. "Pakistan navy planes to get more teeth." Archived 5 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine expressindia.com, 14 February 2007. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- Perrett, Bradley, Sub-hunting, Aviation Week and Space Technology, 8 July 2013, p.27

- Pocock, Chris. The Black Bats: CIA Spy Flights Over China From Taiwan, 1951–1969. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer Publishing, 2010. ISBN 978-0-7643-3513-6.

- "Taiwan". Lockheed Martin. Lockheed Martin. Archived from the original on 14 November 2017. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

P-3- The Taiwan Navy obtained 12 P-3C aircraft under the U.S. government’s Foreign Military Sales program in 2007 which were then modernized to provide an additional 15,000 flight hours.

- "U.S. in deal to refurbish aircraft for Taiwan." Washington Post, 13 March 2009. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- "Contract View". defense.gov. Archived from the original on 31 May 2014.

- "WorldAirForces2016-Corrected.pdf". Flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 19 January 2016. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- Hoyle, Craig. "Singapore interested in ex-US Navy P-3s." Archived 1 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine Flight via flightglobal.com, 15 December 2010. Retrieved: 19 December 2010.

- Eastmunt, Catherine. "P-3B Description." Archived 11 June 2009 at the Wayback Machine Wallops Flight Facility: NASA. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- "DHS Air Assets P-3 AEW: Lockheed Orion P-3B AEW." Archived 29 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine cbp.gov, 11 March 2009. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- "DHS Air Assets P-3 LRT: Lockheed Orion P-3B AEW." Archived 29 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine cbp.gov, 11 March 2009. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- https://registry.faa.gov/aircraftinquiry/NNum_Results.aspx?omni=Home-N-Number&nNumberTxt=N665bd

- "Colorado signs CWN contract for P-3 air tankers" // Archived 26 August 2018 at the Wayback Machine, accessed 28 August 2018 at Fire Aviation.

- "Firefighting." Archived 5 October 2007 at the Wayback Machine aerounion.com, 2003. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- "P-3 Orion Crash Site Michigan – Wreckchasing Message Board". pacaeropress.websitetoolbox.com. Archived from the original on 14 July 2015. Retrieved 8 July 2015.

- "No Title". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- https://aviation-safety.net/database/record.php?id=19680401-0. Retrieved 9 February 2020. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "No Title". aviation-safety.net. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Ranter, Harro and Fabian I. Lujan. "ASN Aircraft accident Lockheed P-3A-50-LO Orion 152155 California." Archived 4 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine Aviation Safety Network, 2005. Retrieved: 28 June 2011.

- "United States Navy Aircrew, 3 June 1972." Archived 19 November 2010 at the Wayback Machine Arlington National Cemetery. Retrieved: 25 January 2011.

- "ASN Aircraft accident, Lockheed P-3C-125-LO Orion, 12 April 1973." Archived 6 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved: 28 June 2011.

- "Lockheed P-3B-80-LO Orion." Archived 9 October 2014 at the Wayback Machine Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved: 21 January 2012.

- "Third VP-23." Archived 9 July 2011 at the Library of Congress Web Archives United States Navy. Retrieved: 21 January 2012.

- "VP-8 Mishaps." Archived 22 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine U.S.Navy Patrol Squadrons. Retrieved: 21 January 2012.

- "The ultimate sacrifice; wreck sites a reminder of military plane disasters." Archived 10 March 2012 at the Wayback Machine Lewiston Sun Journal. Retrieved: 20 January 2012.

- Jampoler, Andrew C.A. Adak: the rescue of Alfa Foxtrot 586. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press, 2003. ISBN 1-59114-412-4.

- "Accident List- United States." Archived 10 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine VPI Book of Remembrance, 27 September 2008. Retrieved: 7 July 2012.

- "VPNAVY – VP-1 Mishap Summary Page – VP Patrol Squadron". vpnavy.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "The Crash of YB-06." Archived 16 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine youtube.com. Retrieved: 7 July 2012.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 29 July 2014. Retrieved 10 March 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident Lockheed P-3C Orion 161762 Crows Landing-Aux Field, CA (NRC)". aviation-safety.net. Archived from the original on 13 September 2016. Retrieved 12 September 2016.

- "VP-50 Crew 2/11 — In Memoriam — VP-50 Crew 2/11, 21 March 1991" Archived 22 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine. U.S. Navy Patrol Squadrons. Retrieved: 25 January 2011.

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- Verbal Account from RAAF Flight Lieutenant Richard Hall

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network

- "A P-3 ditches with Four engines Out, All Survive." http://www.vpnavy.org/vp47ditch.html Archived 25 February 2014 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- Brookes, Andrew (2002). Destination disaster : aviation accidents in the modern age. London: Ian Allan. pp. 101–110. ISBN 0-7110-2862-1.

- Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident Lockheed P-3B Orion N926AU Chico, CA". aviation-safety.net. Archived from the original on 15 October 2017. Retrieved 15 October 2017.

- Jung, Ahmed, Faraz Khan and Jahanzaib Haque. "Navy says PNS base under control after attack." Archived 23 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine tribune.com, 23 May 2011. Retrieved: 23 May 2011.

- Mackey, Robert. "The Lede (blog): Before Attack, Pakistan’s Navy Boasted of Role in Fight Against Taliban." Archived 17 June 2012 at the Wayback Machine The New York Times, 23 May 2011. Retrieved: 10 April 2012.

- "Three US navy planes crushed in Japan snow". AFP. 7 May 2014. Archived from the original on 10 May 2014. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- "Navy Orions likely damaged in hangar collapse". Stars and Stripes. 18 February 2014. Archived from the original on 18 May 2014. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 18 November 2017.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Lockheed AP-3C Orion A9-756". South Australian Aviation Museum. Archived from the original on 4 October 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2018.

- Lambert, Mark; Munson, Kenneth, eds. (1994). Jane's All the World's Aircraft 1994-95 (85th ed.). Coulson, Surrey, UK: Jane's Information Group. pp. 554–557. ISBN 978-0710611604.

- "Specifications: P-3". lockheedmartin.com. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 13 October 2012.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "P-3C Orion – Maritime Patrol and Anti-Submarine Warfare." Archived 5 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine Naval-Technology.Com. Retrieved: 1 August 2010.

- Reade, David (1998). The Age of Orion: The Lockheed P-3 Orion Story. Atglen, Pennsylvania: Schiffer publications. ISBN 0-7643-0478-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Eden, Paul (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Modern Military Aircraft. London: Amber Books, 2004. ISBN 1-904687-84-9.

- McCaughlin, Andrew. "Quiet Achiever." Australian Aviation, December 2007.

- Upgrade of the Orion maritime patrol aircraft fleet : Department of Defence, Defence Materiel Organisation (PDF). Canberra: Australian National Audit Office. 2005. ISBN 0-642-80867-8. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 February 2009.

- Winchester, Jim, ed. (2006). Military Aircraft of the Cold War (The Aviation Factfile). London: Grange plc. ISBN 1-84013-929-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Lockheed P-3 Orion. |

- "AP-3C Orion maritime patrol aircraft." Royal Australian Air Force, 28 November 2008. Retrieved: 14 July 2010.

- ADF-Serials RAAF Lockheed AP-3C, P-3B/C, TAP-3B Orion Page

- P-3 Orion Computer Development History and Project A-New

- P-3C fact file

- P-3 Orion Research Group