Maritime patrol aircraft

A maritime patrol aircraft (MPA), also known as a patrol aircraft, maritime reconnaissance aircraft, or by the older American term patrol bomber, is a fixed-wing aircraft designed to operate for long durations over water in maritime patrol roles — in particular anti-submarine warfare (ASW), anti-ship warfare (AShW), and search and rescue (SAR). It is an important asset among other maritime surveillance resources like satellites, ships, unmanned aerial vehicles or helicopters.[1]. In regard to the ASW role they can carry sonar buoys as well as torpedoes and are supposed to fly at low altitudes.[2]

History

World War I

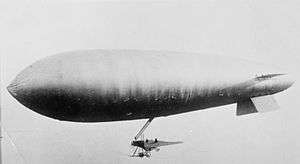

The first aircraft that would now be identified as maritime patrol aircraft were flown by the Royal Naval Air Service and the French Aéronautique Maritime during World War I, primarily on anti-submarine patrols. France, Italy and Austria-Hungary used large numbers of smaller patrol aircraft for the Mediterranean, Adriatic and other coastal areas while the Germans and British fought over the North Sea. At first, blimps and zeppelins were the only aircraft capable of staying aloft for the longer 10 hour patrols whilst carrying a useful payload while shorter-range patrols were mounted with landplanes such as the Sopwith 1½ Strutter. A number of specialized patrol balloons were built, particularly by the British, including the SS class airship of which 158 were built including subtypes. Later in the war, aircraft were also developed specifically for the role including small flying boats such as the FBA Type C as well as large floatplanes such as the Short 184 or flying boats such as the Felixstowe F.3. Developments of the Felixstowe served with the Royal Air Force until the mid 20s, and with the US Navy as the Curtiss F5L and Naval Aircraft Factory PN whose developments saw service until 1938. During the war, Dornier did considerable pioneering work in all aluminium aircraft structures while working for Zeppelin and built four large patrol flying boats, the last of which, the Zeppelin-Lindau Rs.IV influenced development elsewhere resulting in the replacement of wooden hulls with metal ones, such as on the Short Singapore. The success of long range patrol aircraft led to the development of fighters specifically designed to intercept them, such as the Hansa-Brandenburg W.29.

World War II

Many of the World War II patrol airplanes were converted from either bombers or airliners such as the Lockheed Hudson which started out as the Lockheed Model 14 Super Electra, as well as older biplane designs such as the Supermarine Stranraer which had begun to be replaced by monoplanes just before the outbreak of war. The British in particular used obsolete bombers to supplement purpose-built aircraft for maritime patrol, such as the Vickers Wellington and Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley while the US relegated the Douglas B-18 Bolo to the same role until better aircraft became available. Blimps were widely used by the U.S. Navy, especially in the warmer and calmer latitudes of the Caribbean Sea, the Bahamas, Bermuda, the Gulf of Mexico, Puerto Rico, Trinidad, and later the Azores.

Special-purpose aircraft were also used, including the American-made twin-engine Consolidated PBY Catalina flying boats, and the large, four-engine British Short Sunderland flying boats of the Allies. In the Pacific, the Catalina was gradually superseded by the longer-ranged Martin PBM Mariner flying boat. For the Axis Powers, there were the long-range Japanese Kawanishi H6K and Kawanishi H8K flying boats, and the German Blohm & Voss BV 138 diesel-engined trimotor flying boat as well as the converted Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor airliner landplane.

To finally close the Mid-Atlantic gap, or "Black Gap", the British Royal Air Force, the Royal Canadian Air Force, and the U.S. Army Air Forces employed the very long range American Consolidated B-24 Liberator bomber which also saw service in the Pacific as the PB4Y with the U.S. Navy.

New developments in Air-to-Surface Vessel radar and sonobuoys enhanced the ability of aircraft to find and destroy submarines, especially at night and in poor weather, while the need for effective camouflage came under fresh review, with the widespread adoption of white paint schemes in the Atlantic to reduce the warning available to surfaced U-boats, while US Navy aircraft transitioned from an upper light blue-gray and lower white to an all-over dark blue due to the increasing threat of Japanese forces at night-time.

Post–World War II

In the decades following World War II, the patrol duties were partially taken over by aircraft derived from civilian airliners. These had range and performance factors better than most of the wartime bombers. The latest jet-powered bombers of the 1950s did not have the endurance needed for long, overwater patrolling, and they did not have the low loitering speeds necessary for antisubmarine operations.

The RAF also flew a derivative of the Avro Lancaster bomber – the Avro Shackleton – , and then eventually replaced it with the Hawker Siddeley Nimrod, a derivation of the De Havilland Comet airliner.

The U.S. Navy flew a mixture of patrol planes such as the Lockheed P2V Neptune (P2V) and the carrier-based Grumman S-2 Tracker. The P2V was replaced by the Lockheed P-3 Orion, which is still in service after many decades. The P-3 is derived from the 1950s Lockheed Electra airliner with four turboprop engines. Produced in United States, Japan and Canada, the P-3 has been operated by the air forces and navies of United States, Japan, Canada, Australia, Brazil, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, and Taiwan. The Canadian version is called the CP-140 Aurora.

At first, the Royal Australian Air Force and the Royal Australian Navy had to make do with a stretched-fuselage modification of the Avro Lincoln bomber, before replacing those with the P2V and then the P-3C, still in service.

In addition to their ASW and SAR capabilities, most P-3Cs have been modified to carry Harpoon and Maverick missiles for attacking surface ships. American P-3s were formerly armed with the Lulu nuclear depth charge for ASW, but those were removed from the arsenal and scrapped decades ago.

The Soviet Union developed the Ilyushin Il-38 from a civilian airliner. Similarly, the Royal Canadian Air Force derived the Canadair CP-107 Argus from a British airliner. The Argus was superseded by the CP-140 Aurora, derived from the Lockheed Electra.

The French Navy developed the Breguet Atlantic following a Request for Proposal (RFP) from the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO). Some of these were also produced for some other NATO members that were not flying the P-3 or the CP-140.

Japan has developed purpose-designed aircraft as well, the Shin Meiwa PS-1 and ShinMaywa US-2 flying boats, and the Kawasaki P-1 Maritime Patrol Aircraft.

The main threat to NATO maritime supremacy throughout the 1960s, 1970s, and the 1980s was Soviet Navy and Warsaw Pact submarines. These were countered by the NATO fleets, the NATO patrol planes mentioned above, and by sophisticated underwater listening systems. These span the so-called "GIUK Gap" of the North Atlantic that extends from Greenland to Iceland, to the Faroe Islands, to Scotland in the United Kingdom. Air bases for NATO patrol planes have also been located in these areas: U.S. Navy and Canadian aircraft based in Greenland, Iceland, and Newfoundland; British aircraft based in Scotland and Northern Ireland; and Norwegian, Dutch, and German aircraft based in their home countries.

Since the end of the Cold War the threat of a large-scale submarine attack is a remote one, and many of the air forces and navies have been downsizing their fleets of patrol planes. Those still in service are still used for search-and-rescue, counter-smuggling, antipiracy, antipoaching of marine life, the enforcement of the exclusive economic zones, and enforcement of the laws of the seas.

Armament and countermeasures

The earliest patrol aircraft carried bombs and machine guns. Between the wars the British experimented with equipping their patrol aircraft with the COW 37 mm gun. During World War II, depth charges that could be set to detonate at specific depths, and later when in proximity with large metal objects replaced "anti-submarine" bombs that detonated on contact.

Patrol aircraft also carried defensive armament which was necessary when patrolling areas close to enemy territory such as Allied operations in the Bay of Biscay targeting U-boats starting out from their base.

As a result of Allied successes with patrol aircraft against U-boats, the Germans introduced U-flak (submarines equipped with more antiaircraft weaponry) to escort U-boats out of base and encouraged commanders to remain on the surface and fire back at attacking craft rather than trying to escape by diving. However, U-flak was short lived as opposing pilots adapted their tactics. Equipping submarines with radar-warning devices and the snorkel made them harder to find.

To counter the German long-range patrol aircraft that targeted merchant convoys, the Royal Navy introduced the "CAM ship", which was a merchant vessel equipped with a lone fighter plane which could be launched once to engage the enemy planes.

Then the small escort carriers of WW II became available to cover the deep oceans, and the land air bases in the Azores became available in mid-1943 from Portugal.

Sensors

Maritime patrol aircraft are typically fitted with a wide range of sensors:[3]

- Radar to detect surface shipping movements. Radar can also detect a submarine snorkel or periscope, and the wake it creates.

- Magnetic anomaly detector (MAD) to detect the iron in a submarine's hull. The MAD sensor is typically mounted on an extension from the tail or is trailed behind the aircraft on a cable to minimize interference from the metal in the rest of the aircraft;

- Sonobuoys - self-contained sonar transmitter/receivers dropped into the water to transmit data back to the aircraft for analysis;

- ELINT sensors to monitor communications and radar emissions;

- Infrared cameras (sometimes referred to as FLIR for forward looking infrared) for detecting exhaust streams and other sources of heat and are useful in monitoring shipping movements and fishing activity.

- Visual inspection using the aircrew's eyes, in some cases aided by searchlights or flares.

A modern military maritime patrol aircraft typically carries a dozen or so crew members, including relief flight crews, to effectively operate the equipment for 12 hours or more at a time.

Examples

References

- Defence Committee, James Arbuthnot, Great Britain: Parliament: House of Commons (2012). Future Maritime Surveillance. Authority of the House of Commons London: The Stationery Office Limited. p. 11. ISBN 9780215048479. "Fifth Report of Session 2012-13, Vol. 1", Google Books

- Panayirci, E.; Isik, C.; Ince, A.N.; Topuz, E. (2012). "5: Sensor Platforms". Principles of Integrated Maritime Surveillance Systems. United States: Springer US. p. 188. ISBN 9781461552710. , Google Books

- Global Security.com - ASW Sensors accessdate:March 2014