Little penguin

The little penguin (Eudyptula minor) is the smallest species of penguin. It grows to an average of 33 cm (13 in) in height and 43 cm (17 in) in length, though specific measurements vary by subspecies.[2][3] It is found on the coastlines of southern Australia and New Zealand, with possible records from Chile. In Australia, they are often called fairy penguins because of their small size. In New Zealand, they are more commonly known as little blue penguins or blue penguins owing to their slate-blue plumage; they are also known by their Māori name: kororā.

| Little penguin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Near burrow at night, Bruny Island, Tasmania, Australia | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Sphenisciformes |

| Family: | Spheniscidae |

| Genus: | Eudyptula |

| Species: | E. minor |

| Binomial name | |

| Eudyptula minor (J.R.Forster, 1781) | |

Taxonomy

The little penguin was first described by German naturalist Johann Reinhold Forster in 1781. Several subspecies are known, but a precise classification of these is still a matter of dispute. The holotypes of the subspecies E. m. variabilis[4] and Eudyptula minor chathamensis[5] are in the collection of the Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. The white-flippered penguin is sometimes considered a subspecies, sometimes a distinct species, and sometimes a morph.

Genetic analyses indicate that the Australian and Otago (southeastern coast of South Island) little penguins may constitute a distinct species.[6] In this case the specific name minor would devolve on it, with the specific name novaehollandiae suggested for the other populations.[7] This interpretation suggests that E. novaehollandiae individuals arrived in New Zealand between AD 1500 and 1900 while the local E. minor population had declined, leaving a genetic opening for a new species.[8][9]

Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA evidence suggests the split between Eudyptula and Spheniscus occurred around 25 million years ago, with the ancestors of the white-flippered and little penguins diverging about 2.7 million years ago.[10]

Description

Like those of all penguins, the little penguin's wings have developed into flippers used for swimming. The little penguin typically grows to between 30 and 33 cm (12 and 13 in) tall and usually weighs about 1.5 kg on average (3.3 lb). The head and upper parts are blue in colour, with slate-grey ear coverts fading to white underneath, from the chin to the belly. Their flippers are blue in colour. The dark grey-black beak is 3–4 cm long, the irises pale silvery- or bluish-grey or hazel, and the feet pink above with black soles and webbing. An immature individual will have a shorter bill and lighter upperparts.[11]

Like most seabirds, they have a long lifespan. The average for the species is 6.5 years, but flipper ringing experiments show in very exceptional cases up to 25 years in captivity.[12]

Distribution and habitat

The little penguin breeds along the entire coastline of New Zealand (including the Chatham Islands), and southern Australia (including roughly 20,000 pairs[13] on Babel Island). Australian colonies exist in New South Wales, Victoria, Tasmania, South Australia, Western Australia and the Jervis Bay Territory. Little penguins have also been reported from Chile (where they are known as pingüino pequeño or pingüino azul) (Isla Chañaral 1996, Playa de Santo Domingo, San Antonio, 16 March 1997) and South Africa, but it is unclear whether these birds were vagrants. As new colonies continue to be discovered, rough estimates of the world population circa 2011 were around 350,000-600,000 animals.[3]

New Zealand

Overall, little penguin populations in New Zealand have been decreasing. Some colonies have become extinct and others continue to be at risk.[3] Some new colonies have been established in urban areas.[2] The species is not considered endangered in New Zealand, with the exception of the white-flippered subspecies found only on Banks Peninsula and nearby Motunau Island. Since the 1960s, the mainland population has declined by 60-70%; though a small increase has occurred on Motunau Island. A colony exists in Wellington Harbor on Matiu/Somes Island.

Australia

Australian little penguin colonies primarily exist on offshore islands, where they are protected from feral terrestrial predators and human disturbance. Colonies are found from Port Stephens in northern New South Wales around the southern coast to Fremantle, Western Australia. Foraging penguins have occasionally been seen as far north as Southport, Queensland[14] and Shark Bay, Western Australia.[15]

New South Wales

An endangered population of little penguins exists at Manly, in Sydney's North Harbour. The population is protected under the NSW Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995[16] and has been managed in accordance with a Recovery Plan since the year 2000. The population once numbered in the hundreds, but has decreased to around 60 pairs of birds. The decline is believed to be mainly due to loss of suitable habitat, attacks by foxes and dogs and disturbance at nesting sites.[17]

The largest colony in New South Wales is on Montague Island. Up to 8000 breeding pairs are known to nest there each year.[18] Additional colonies exist on the Tollgate Islands in Batemans Bay.

Additional colonies exist in the Five Islands Nature Reserve, offshore from Port Kembla,[19] and at Boondelbah Island, Cabbage Tree Island and the Broughton Islands off Port Stephens.[20][21]

Jervis Bay Territory

A population of about 5,000 breeding pairs exists on Bowen Island. The colony has increased from 500 pairs in 1979 and 1500 pairs in 1985. During this time, the island was privately leased. The island was vacated in 1986 and is currently controlled by the federal government.[22]

South Australia

In South Australia, many little penguin colony declines have been identified across the state. In some cases, colonies have declined to extinction (including the Neptune Islands, West Island, Wright Island, Pullen Island and several colonies on western Kangaroo Island), while others have declined from thousands of animals to few (Granite Island and Kingscote). The only known mainland colony exists at Bunda Cliffs on the state's far west coast, though colonies have existed historically on Yorke Peninsula.[23] A report released in 2011 presented evidence supporting the listing of the statewide population or the more closely monitored sub-population from Gulf St. Vincent as Vulnerable under South Australia's National Parks & Wildlife Act 1972.[24] As of 2014, the little penguin is not listed as a species of conservation concern,[25] despite ongoing declines at many colonies.

Tasmania

Tasmanian little penguin population estimates range from 110,000–190,000 breeding pairs of which less than 5% are found on mainland Tasmania. Ever-increasing human pressure is predicted to result in the extinction of colonies on mainland Tasmania.[26]

Victoria

.jpg)

St Kilda breakwater

The largest colony of little penguins in Victoria is located at Phillip Island, where the nightly 'parade' of penguins across Summerland Beach has been a major tourist destination, and more recently a major conservation effort, since the 1920s. Phillip Island is home to an estimated 32,000 breeding adults.[27] Little penguins can also be seen in the vicinity of the St Kilda, Victoria pier and breakwater. The breakwater is home to a colony of little penguins which have been the subject of a conservation study since 1986.[28]

Little penguin habitats also exist at a number of other locations, including London Arch and The Twelve Apostles along the Great Ocean Road, Wilson's Promontory and Gabo Island.[29]

Western Australia

The largest colony of little penguins in Western Australia is believed to be located on Penguin Island, where an estimated 1,000 pairs nest during winter.[30] Penguins are also known to nest on Garden Island and Carnac Island which lie north of Penguin Island. Many islands along Western Australia's southern coast are likely to support little penguin colonies, though the status of these populations is largely unknown. An account of little penguins on Bellinger Island published in 1928 numbered them in their thousands. Visiting naturalists in November 1986 estimated the colony at 20 breeding pairs.[31] The account named another substantial colony 12 miles from Bellinger Island and the same distance from Cape Pasley.[32] Little penguins are known to breed on some islands of the Recherche Archipelago, including Woody Island where day-tripping tourists can view the animals. A penguin colony exists on Mistaken Island in King George Sound near Albany.[33] Historical accounts of little penguins on Newdegate Island at the mouth of Deep River[34] and on Breaksea Island near Torbay also exist. West Australian little penguins have been found to forage as far as 150 miles north of Geraldton (south of Denham and Shark Bay).[15]

Behaviour

Little penguins are diurnal and like many penguin species, spend the largest part of their day swimming and foraging at sea. During the breeding and chick-rearing seasons, little penguins leave their nest at sunrise, forage for food throughout the day and return to their nests just after dusk. Thus, sunlight, moonlight and artificial lights can affect the behaviour of attendance to the colony.[35] Also, increased wind speeds negatively affect the little penguins' efficiency in foraging for chicks, but for reasons not yet understood.[36] Little penguins preen their feathers to keep them waterproof. They do this by rubbing a tiny drop of oil onto every feather from a special gland above the tail.

Range

Tagged or banded birds later recaptured or found deceased have shown that individual birds can travel great distances during their lifetimes. In 1984, a penguin that had been tagged at Gabo Island in eastern Victoria was found dead at Victor Harbor in South Australia. Another little penguin was found near Adelaide in 1970 after being tagged at Phillip Island in Victoria the previous year.[37] In 1996, a banded penguin was found dead at Middleton. It had been banded in 1991 at Troubridge Island in Gulf St Vincent, South Australia.[38]

The little penguin's foraging range is quite limited in terms of distance from shore when compared to seabirds that can fly.[39]

Feeding

Little penguins feed by hunting small clupeoid fish, cephalopods and crustaceans, for which they travel and dive quite extensively[40][41] including to the sea floor. Researcher Tom Montague studied a Victorian population for two years in order to understand its feeding patterns. Montague's analysis revealed a penguin diet consisting of 76% fish and 24% squid. Nineteen fish species were recorded, with pilchard and anchovy dominating. The fish were usually less than 10 cm long and often post-larval or juvenile. Less common little penguin prey include: crab larvae, eels, jellyfish and seahorses.[39] In New Zealand, important little penguin prey items include arrow squid, slender sprat, Graham's gudgeon, red cod and ahuru.[42]

Since the year 2000, the little penguins of Port Phillip Bay's diet has consisted mainly of barracouta, anchovy, and arrow squid. Pilchards previously featured more prominently in southern Australian little penguin diets prior to mass sardine mortality events of the 1990s. These mass mortality events affected sardine stocks over 5,000 kilometres of coastline.[43] Jellyfish including species in the genera Chrysaora and Cyanea were found to be actively sought-out food items, while they previously had been thought to be only accidentally ingested. Similar preferences were found in the Adélie penguin, yellow-eyed penguin and Magellanic penguin.[44] A important crustacean present in the little penguin diet is the krill, Nyctiphanes australis, which surface-swarms during the day.[39]

Little penguins are generally inshore feeders.[45] The use of data loggers has shown that in the diving behaviour of little penguins, 50% of dives go no deeper than 2 m, and the mean diving time is 21 seconds.[46] In the 1980s, average little penguin dive time was estimated to be 23-24 seconds.[39] The maximum recorded depth and time submerged are 66.7 metres and 90 seconds respectively.[47]

Parasites

Little penguins play an important role in the ecosystem as not only a predator to parasites but also a host. Recent studies have shown a new species of feather mite that feeds on the preening oil on the feathers of the penguin.[48] Little penguins preen their mates to strengthen social bonds and remove parasites, especially from their partner's head where self-preening is difficult.[39]

Reproduction

Little penguins reach sexual maturity at different ages. The female matures at two years old and the male at three years old.

Between June and August, males return to shore to renovate or dig new burrows and display to attract a mate for the season. Males compete for partners with their displays. Breeding occurs annually, but the timing and duration of the breeding season varies from location to location and from year to year. Breeding occurs during spring and summer when oceans are most productive and food is plentiful.

Little penguins remain faithful to their partner during a breeding season and whilst hatching eggs. At other times of the year they tend to swap burrows. They exhibit site fidelity to their nesting colonies and nesting sites over successive years. Little penguins can breed as isolated pairs, in colonies, or semi-colonially.[42]

Nesting

Penguins' nests vary depending on the available habitat. They are established close to the sea in sandy burrows excavated by the birds' feet or dug previously by other animals. Nests may also be made in caves, rock crevices, under logs or in or under a variety of man-made structures including nest boxes, pipes, stacks of wood or timber, and buildings. Nests have been occasionally observed to be shared with prions, while some burrows are occupied by short-tailed shearwaters and little penguins in alternating seasons. In the 1980s, little was known on the subject of competition for burrows between bird species.[39]

Timing

The timing of breeding seasons varies across the species' range. In the 1980s, the first egg laid at a penguin colony on Australia's eastern coast could be expected to come as early as May or as late as October. Eastern Australian populations (including at Phillip Island, Victoria) lay their eggs from July to December.[49] In South Australia's Gulf St. Vincent, eggs are laid between April and October[50] and south of Perth in Western Australia, peak egg-laying occurred in June and continued until mid-October (based on observations from the 1980s).[39]

Male and female birds share incubating and chick-rearing duties. They are the only species of penguin capable of producing more than one clutch of eggs per breeding season, but few populations do so. In ideal conditions, a penguin pair is capable of raising two or even three clutches of eggs over an extended season, which can last between eight and twenty-eight weeks.[39]

The one or two (on rare occasions, three) white or lightly mottled brown eggs are laid between one and four days apart. Each egg typically weighs around 55 grams at time of laying.[39] Incubation takes up to 36 days. Chicks are brooded for 18–38 days and fledge after 7–8 weeks.[42] On Australia's east coast, chicks are raised from August to March.[49] In Gulf St. Vincent, chicks are raised from June through November.[50]

Little penguins typically return to their colonies to feed their chicks at dusk. The birds tend to come ashore in small groups to provide some defence against predators, which might otherwise pick off individuals. In Australia, the strongest colonies are usually on cat-free and fox-free islands. However, the population on Granite Island (which is a fox, cat and dog-free island) has been severely depleted, from around 2000 penguins in 2001 down to 22 in 2015. Granite Island is connected to the mainland via a timber causeway.

Native predators

Predation by native animals is not considered a threat to little penguin populations, as these predators' diets are diverse. Large native reptiles including the tiger snake and Rosenberg's goanna[51] are known to take little penguin chicks and blue-tongued lizards are known to take eggs.[39] At sea, little penguins are eaten by long-nosed fur seals. A study conducted by researchers from the South Australian Research and Development Institute found that roughly 40 percent of seal droppings in South Australia's Granite Island area contained little penguin remains.[52][53] Other marine predators include sharks and barracouta.[39]

Little penguins are also preyed upon by white-bellied sea eagles. These large birds-of-prey are endangered in South Australia and not considered a threat to colony viability there. Other avian predators include: kelp gulls, pacific gulls, brown skuas and currawongs.[39]

In Victoria, at least one penguin death has been attributed to a water rat.[54]

Mass mortalities

A mass mortality event occurred in Port Phillip Bay in March 1935. The event coincided with moulting and deaths were attributed to fatigue.[55] Another event occurred at Phillip Island in Victoria in 1940. The population there was believed to have fallen from 2000 birds to 200. Dead birds were allegedly in healthy-looking condition so speculation pointed to a disease or pathogen.[56]

Citizens have raised concerns about mass mortality of penguins alleging a lack of official interest in the subject.[57] Discoveries of dead penguins in Australia should be reported to the corresponding state's environment department. In South Australia, a mortality register was established in 2011.

Relationship with humans

Little penguins have long been a curiosity to humans and to children in particular.[58] Captive animals are often exhibited in zoos. Over time attitudes towards penguins have evolved from direct exploitation (for meat, skins and eggs) to the development of tourism ventures, conservation management and the protection of both birds and their habitat.

Direct exploitation

During the 19th and 20th centuries, little penguins were shot for "sport", killed for their skins, captured for amusement and eaten by ship-wrecked sailors and castaways to avoid starvation.[59][60][61][62] Their eggs were also collected for human consumption by indigenous[39] and non-indigenous people.[63] In 1831, N. W. J. Robinson noted that penguins were typically soaked in water for many days to tenderise the meat before eating.[39]

One of the colonies raided for penguin skins was Lady Julia Percy Island in Victoria.[64] The following directions for preparing penguin skin were published in The Chronicle in 1904:[65]

'F.W.M.,' Port Lincoln. — To clean penguin skins, scrape off as much fat as you can with a blunt knife. Then peg the skin out carefully, stretching it well. Let it remain in the sun till most of the fat is dried out of it, then rub with a compound of powdered alum, salt, and pepper in about equal proportions. Continue to rub this on at intervals until the skin becomes soft and pliable.

An Australian taxidermist was once commissioned to make a woman's hat for a cocktail party from the remains of a dead little penguin. The newspaper described it as "a smart little toque of white and black feathers, with black flippers set at a jaunty angle on the crown."[66]

In the 20th century, little penguins have been maliciously attacked by humans, used as bait to catch Southern rock lobster,[39] used to free snagged fishing tackle,[67] killed as incidental bycatch by fishermen using nets, and killed by vehicle strikes on roads and on the water.[68]

In the late 20th and 21st centuries, more mutually beneficial relationships between penguins and humans developed. The sites of some breeding colonies have become carefully-managed tourist destinations which provide an economic boost for coastal and island communities in Australia and New Zealand. These locations also often provide facilities and volunteer staff to support population surveys, habitat improvement works and little penguin research programs.

Tourism

At Phillip Island, Victoria, a viewing area has been established at the Phillip Island Nature Park to allow visitors to view the nightly "penguin parade". Lights and concrete stands have been erected to allow visitors to see but not photograph or film the birds (this is because it can blind or scare them) interacting in their colony.[69] In 1987, more international visitors viewed the penguins coming ashore at Phillip Island than visited Uluru. In the financial year 1985-86, 350,000 people saw the event, and at that time audience numbers were growing 12% annually.[70]

In Bicheno, Tasmania, evening penguin viewing tours are offered by a local tour operator at a rookery on private land.[71] A similar sunset tour is offered at Low Head, near the mouth of the Tamar River on Tasmania's north coast.[72] Observation platforms exist near some of Tasmania's other little penguin colonies, including Bruny Island and Lillico Beach near Devonport.[73]

South of Perth, Western Australia, visitors to Penguin Island are able to view penguin feeding within a penguin rehabilitation centre and may also encounter wild penguins ashore in their natural habitat. The island is accessible via a short passenger ferry ride, and visitors depart the island before dusk to protect the colony from disturbance.

Visitors to Kangaroo Island, South Australia, have nightly opportunities to observe penguins at the Kangaroo Island Marine Centre in Kingscote and at the Penneshaw Penguin Centre.[74] Granite Island at Victor Harbor, South Australia continues to offer guided tours at dusk, despite its colony dropping from thousands in the 1990s to dozens in 2014.[75] There is also a Penguin Centre located on the island where the penguins can be viewed in captivity.[76]

In the Otago, New Zealand town of Oamaru, visitors may view the birds returning to their colony at dusk.[77] In Oamaru it is not uncommon for penguins to nest within the cellars and foundations of local shorefront properties, especially in the old historic precinct of the town. More recently, little penguin viewing facilities have been established at Pilots Beach on the Otago Peninsula in Dunedin, New Zealand. Here visitors are guided by volunteer wardens to watch penguins returning to their burrows at dusk.[78]

Threats

Prey availability

Food availability appears to strongly influence the survival and breeding success of little penguin populations across their range.[39]

Variation in prey abundance and distribution from year to year causes young birds to be washed up dead from starvation or in weak condition.[26] This problem is not constrained to young birds, and has been observed throughout the 20th century.[79] The breeding season of 1984-1985 in Australia was particularly bad, with minimal breeding success. Eggs were deserted prior to hatching and many chicks starved to death. Malnourished penguin carcasses were found washed up on beaches and the trend continued the following year. In April 1986, approximately 850 dead penguins were found washed ashore in south-western Victoria. The phenomenon was ascribed to lack of available food.[39]

There are two seasonal peaks in the discovery of dead little penguins in Victoria. The first follows moult and the second occurs in mid-winter. Moulting penguins are under stress, and some return to the water in a weak condition afterwards.[39] Mid-winter marks the season of lowest prey availability, thus increasing the probability of malnutrition and starvation.

In 1990, 24 dead penguins were found in the Encounter Bay area in South Australia during a week spanning late April to early May. A State government park ranger explained that many of the birds were juvenile and had starved after moulting.[80]

In 1995 pilchard mass mortality events occurred, which reduced the penguins' available prey and resulted in starvation and breeding failure.[81] Another similar event occurred in 1999. Both mortality events were attributed to an exotic pathogen which spread across the entire Australian population of the fish, reducing the breeding biomass by 70%. Crested tern and gannet populations also suffered following these events.[82]

In 1995, 30 dead penguins were found ashore between Waitpinga and Chiton Rocks in the Encounter Bay area. The birds has suffered severe bacterial infections and the mortalities may have been linked to the mass mortality of pilchards that resulted from the spread of an exotic pathogen that year.[83]

In the late 1980s, it was believed that penguins did not compete with the fishing industry, despite anchovy being commercially caught.[39] That assertion was made prior to the establishment and development of South Australia's commercial pilchard fishery in the 1990s. In South Africa, the overfishing of species of preferred penguin prey has caused Jackass penguin populations to decline. Overfishing is a potential (but not proven) threat to the little penguin.[39]

Introduced predators

Introduced mammalian predators present the greatest terrestrial risk to little penguins and include cats, dogs, rats, foxes, ferrets and stoats.[2][3][84][85][86]

Due to their diminutive size and the introduction of new predators, some colonies have been reduced in size by as much as 98% in just a few years, such as the small colony on Middle Island, near Warrnambool, Victoria, which was reduced from approximately 600 penguins in 2001 to less than 10 in 2005. Because of this threat of colony collapse, conservationists successfully pioneered an experimental technique using Maremma Sheepdogs to protect the colony and fend off would-be predators,[87] with numbers reaching 100 by 2017.[88]

Uncontrolled dogs or feral cats can have sudden and severe impacts on penguin colonies (more than the penguin's natural predators) and may kill many individuals. Examples of colonies affected by dog attacks include Manly, New South Wales,[89] Penneshaw, South Australia,[90] Red Chapel Beach,[91] Wynyard[92] and Low Head, Tasmania,[93] Penguin Island, Western Australia and Little Kaiteriteri Beach, New Zealand.[94] Cats have been recorded preying on penguin chicks at Emu Bay on Kangaroo Island in South Australia.[51] Paw prints at an attack site at Freeman's Knob, Encounter Bay, showed that the dog responsible was small, roughly the size of a terrier. The single attack may have rendered the small colony extinct.[95]

A suspected stoat or ferret attack at Doctor's Point near Dunedin, New Zealand claimed the lives of 29 little blue penguins in November 2014.[96]

Foxes have been known to prey on little penguins since at least the early 20th century.[97][98] A fox was believed responsible for the deaths of 53 little penguins over several nights on Granite Island in 1994.[99] In June 2015, 26 penguins from the Manly colony were killed in 11 days. A fox believed responsible was eventually shot in the area and an autopsy is expected to prove or disprove its involvement.[85] In November 2015 a fox entered the little penguin enclosure at the Melbourne Zoo and killed 14 penguins, prompting measures to further "fox proof" the enclosure.[100]

Human development

The impacts of human habitation in proximity to little penguin colonies include collisions with vehicles,[101] direct harassment, burning and clearing of vegetation and housing development.[26] In 1950, roughly a hundred little penguins were allegedly burned to death near The Nobbies at Port Phillip Bay during a grass fire lit intentionally by a grazier for land management purposes.[102] It was later reported that the figure had been overstated.[103] The matter was resolved when the grazier offered to return land to the custody of the State for the future protection of the colony.[104][105]

The Conservation Council of Western Australia has expressed opposition to the proposed development of a marina and canals at Mangles Bay, in close proximity to penguin colonies at Penguin Island and Garden Island. Researcher Belinda Cannell of Murdoch University found that over a quarter of penguins found dead in the area had been killed by boats. Carcasses had been found with heads, flippers or feet cut off, cuts on their backs and ruptured organs. The development would increase boat traffic and result in more penguin deaths.[106]

Human interference

Penguins are vulnerable to interference by humans, especially while they are ashore during moult or nesting periods.

In 1930 in Tasmania, it was believed that little penguins were competing with mutton-birds, which were being commercially exploited. An "open season" in which penguins would be permitted to be killed was planned in response to requests from members of the mutton-birding industry.[107]

In the 1930s, an arsonist was believed to have started a fire on Rabbit Island near Albany, Western Australia- a known little penguin rookery. Visitors later reported finding dead penguins there with their feet burned off.[108]

In 1949, penguins on Phillip Island in Victoria became victims of human cruelty, with some kicked and others thrown off a cliff and shot at. These acts of cruelty prompted the state government to fence off the rookeries.[109] In 1973, ten dead penguins and fifteen young seagulls were found dead on Wright Island in Encounter Bay, South Australia. It was believed that they were killed by people poking sticks down burrows before scattering the dead bodies around.[110] In 1983 one penguin was found dead and another injured at Encounter Bay, both by human interference. The injured bird was euthanased.[111]

More recent examples of destructive interference can be found at Granite island, where in 1994 a penguin chick was taken from a burrow and abandoned on the mainland, a burrow containing penguin chicks was trampled and litter was discarded down active burrows.[112] In 1998, two incidents in six months resulted in penguin deaths. The latter, which occurred in May, saw 13 penguins apparently kicked to death.[113][114] In March 2016, two little penguins were kicked and attacked by humans during separate incidents at the St Kilda colony, Victoria.[115]

In 2018, 20-year-old Tasmanian man Joshua Leigh Jeffrey was fined $82.50 in court costs and sentenced to 49 hours of community service at Burnie Magistrates Court after killing nine little penguins at Sulphur Creek in North West Tasmania on 1 January 2016 by beating them with a stick.[116] Dr Eric Woehler from conservation group Birds Tasmania denounced the perceived leniency of the sentence, which he said placed minimal value on Tasmania's wildlife and set an "unwelcome precedent".[117] Following an appeal by prosecutors, Jeffrey had his sentence doubled on 15 October 2018. The office of the Director of Public Prosecutions said it considered the original sentence to be manifestly inadequate. The original sentence was set aside, and Jeffrey was sentenced to two months in prison, suspended on the condition of him committing no offences for a year that are punishable by imprisonment. His community order was also doubled to 98 hours.[118]

Also in 2018, a dozen little penguin carcasses were found in a garbage bin at Low Head, Tasmania prompting an investigation into the causes of death.[119]

Interactions with fishing

Some little penguins are drowned when amateur fishermen set gill nets near penguin colonies.[120] Discarded fishing line can also present an entanglement risk and contact can result in physical injury, reduced mobility or drowning.[26] In 2014, a group of 25 dead little penguins was found on Altona Beach in Victoria. Necropsies concluded that the animals had died after becoming entangled in net fishing equipment, prompting community calls for a ban on net fishing in Port Phillip Bay.[121]

In the 20th century, little penguins were intentionally shot or caught by fishermen to use as bait in pots for catching crayfish (Southern rock lobster) or by line fishermen.[122][123][124] Colonies were targeted for this purpose in various parts of Tasmania[125][126] including Bruny Island[127] and West Island, South Australia.

A study in Perth from 2003 to 2012 found that the main cause of mortality was trauma, most likely from watercraft, leading to a recommendation for management strategies to avoid watercraft strikes.[128]

Oil spills

Oil spills can be lethal for penguins and other sea birds.[129] Oil is toxic when ingested and penguins' buoyancy and the insulative quality of their plumage is damaged by contact with oil.[26][39] Little penguin populations have been significantly affected during two major oil spills at sea: the Iron Baron oil spill off Tasmania's north coast in 1995 and the grounding of the Rena off New Zealand in 2011. In 2005, a 10-year post-mortem reflection on the Iron Baron incident estimated penguin fatalities at 25,000.[130] The Rena incident killed 2,000 seabirds (including little penguins) directly, and killed an estimated 20,000 in total based on wider ecosystem impacts.[131][132]

Another oil spill or dumping event claimed the lives of up to 120 little penguins which were found oiled, deceased and ashore near Warnambool in 1990. A further 104 penguins were taken into care for cleaning. The waters west of Cape Otway were polluted with bunker oil. The source was unknown at the time and an investigation was started into three potentially responsible vessels.[133] Earlier oil spill or oil dumping events impacted little penguins at various locations in the 1920s,[134] 1930s,[135]1940s,[136][137] and in the 1950s.[138][139]

Plastic pollution

Plastics are swallowed by little penguins, who mistake them for prey items. They present a choking hazard and also occupy space in the animal's stomach. Indigestible material in a penguin's stomach can contribute to malnutrition or starvation. Other larger plastic items, such as bottle packaging rings, can become entangled around penguins' necks, affecting their mobility.[26][39]

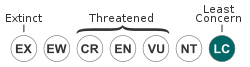

Climate change

Heat waves can result in mass mortality episodes at nesting sites, as the penguins have poor physiological adaptations towards losing heat.[140] Climate change is recognised as a threat, though currently it is assessed to be less significant than others.[1] Efforts are being made to protect penguins in Australia from the likely future increased occurrence of extreme heat events.[140]

Variation in the timing of seasonal ocean upwelling events, such as the Bonney Upwelling, which provide abundant nutrients vital to the growth and reproduction of primary producers at the base of the food chain, may adversely affect prey availability, and the timing and success or failure of little penguin breeding seasons.[141]

Conservation

Little penguins are protected from various threats under different legislation in different jurisdictions. The table below may not be exhaustive.

| Location | Status | Register or Legislation |

|---|---|---|

| Australia (Commonwealth waters) | Listed marine species. | Environment Protection Biodiversity Conservation (EPBC) Act 1999[142] |

| Western Australia | Protected fauna. | Wildlife Conservation Act 1950[143] |

| South Australia | Protected animal.

Mandatory reporting for fisheries interactions. |

National Parks & Wildlife Act 1972[144]

Fisheries Management Act 2007 |

| Victoria | Protected wildlife.

Mandatory reporting for fisheries interactions. |

Wildlife Act 1975[145]

Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988[146] |

| Tasmania | Protected wildlife.

Penguins declared "sensitive wildlife" and some colony sites declared "sensitive areas". |

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1970[147]

Dog Control Act 2000[148] |

| New South Wales | Threatened species (Manly colony only) .

Manly colony declared "Critical Habitat". |

Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016

Threatened Species Conservation Act 1995[149] |

| New Zealand | At risk - declining. | Wildlife Act 1953[150] |

Management of introduced predators

On land, little penguins are vulnerable to attack from domestic and feral dogs and cats. Attacks at Encounter Bay,[151] on Kangaroo Island,[90] at Manly[89] in Tasmania[91] and in New Zealand[94] have resulted in significant impacts to different populations. Management strategies to mitigate the risk of attack include establishing dog-free zones near penguin colonies[92] and introducing regulations to ensure dogs to remain on leashes at all times in adjacent areas.

Little penguins on Middle Island off Warrnambool, Victoria were subject to heavy predation by foxes, which were able to reach the island at low tide by a tidal sand bridge. The deployment of Maremma sheepdogs to protect the penguin colony has deterred the foxes and enabled the penguin population to rebound.[152][153] This is in addition to the support from groups of volunteers who work to protect the penguins from attack at night. The first Maremma sheepdog to prove the concept was Oddball, whose story inspired a feature film of the same name, released in 2015.[154][155] In December 2015, the BBC reported, "The current dogs patrolling Middle Island are Eudy and Tula, named after the scientific term for the fairy penguin: Eudyptula. They are the sixth and seventh dogs to be used and a new puppy is being trained up [...] to start work in 2016.[154]

In Sydney, snipers have been used to protect a colony of little penguins. This effort is in addition to support from local volunteers who work to protect the penguins from attack at night.[156]

Habitat restoration

Several efforts have been made to improve breeding sites on Kangaroo Island, including augmenting habitat with artificial burrows and revegetation work. The Knox School's habitat restoration efforts were filmed and broadcast in 2008 by Totally Wild.

In 2019, concrete nesting "huts" were made for the little penguins of Lion Island in the mouth of the Hawkesbury River in New South Wales, Australia. The island was ravaged by a fire which began with a lightning strike and destroyed 85% of the penguin's natural habitat.[157]

Weed control undertaken by the Friends of Five Islands in New South Wales helps improve prospects of breeding success for seabirds, including the little penguin.[158] The main problem species on the Five Islands are kikuyu grass and coastal morning glory.[159] The weeding work has resulted in increasing numbers of little penguin burrows in the areas weeded and the return of the white-faced storm petrel to the island after a 56 year breeding absence.[160]

Zoological exhibits

Zoological exhibits featuring purpose-built enclosures for little penguins can be seen in Australia at the Adelaide Zoo, Melbourne Zoo, the National Zoo & Aquarium in Canberra, Perth Zoo, Caversham Wildlife Park (Perth), Ballarat Wildlife Park, Sea Life Sydney Aquarium[161] and the Taronga Zoo in Sydney.[162][163][164][165][166][167][168] Enclosures include nesting boxes or similar structures for the animals to retire into, a reconstruction of a pool and in some cases, a transparent aquarium wall to allow patrons to view the animals underwater while they swim.

A little penguin exhibit exists at Sea World, on the Gold Coast, Queensland, Australia. In early March, 2007, 25 of the 37 penguins died from an unknown toxin following a change of gravel in their enclosure.[169][170][171] It is still not known what caused the deaths of the little penguins, and it was decided not to return the 12 surviving penguins to the same enclosure where the penguins became ill.[172] A new enclosure for the little penguin colony was opened at Sea World in 2008.[173]

In New Zealand, little penguin exhibits exist at the Auckland Zoo, the Wellington Zoo and the National Aquarium of New Zealand.[174] Since 2017, the National Aquarium of New Zealand, has featured a monthly "Penguin of the Month" board, declaring two of their resident animals the "Naughty" and "Nice" penguin for that month. Photos of the board have gone viral and gained the aquarium a large worldwide social media following.[175]

A colony of little blue penguins exists at the New England Aquarium in Boston, Massachusetts. The penguins are one of three species on exhibit and are part of the Association of Zoos and Aquariums' Species Survival Plan for little blue penguins.[176] Little penguins can also be seen at the Louisville Zoo[177] and the Bronx Zoo.[178]

Mascots and logos

Linus Torvalds, the original creator of Linux (a popular operating system kernel), was once pecked by a little penguin while on holiday in Australia. Reportedly, this encounter encouraged Torvalds to select Tux as the official Linux mascot.[179]

A Linux kernel programming challenge called the Eudyptula Challenge[180] has attracted thousands of persons; its creator(s) use the name "Little Penguin".

Penny the Little Penguin was the mascot for the 2007 FINA World Swimming Championships held in Melbourne, Victoria.[181][182]

See also

References

- BirdLife International (2012). "Eudyptula minor". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Grabski, Valerie (2009). "Little Penguin - Penguin Project". Penguin Sentinels/University of Washington. Archived from Little the original Check

|url=value (help) on 16 December 2011. Retrieved 25 November 2011. - Dann, Peter. "Penguins: Little (Blue or Fairy) Penguins - Eudyptula minor". International Penguin Conservation Work Group. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- "Eudyptula minor variabilis; holotype". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- "Eudyptula minor chathamensis; holotype". Collections Online. Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- Banks, Jonathan C.; Mitchell, Anthony D.; Waas, Joseph R. & Paterson, Adrian M. (2002): An unexpected pattern of molecular divergence within the blue penguin (Eudyptula minor) complex. Notornis 49(1): 29–38. PDF fulltext

- Grosser, Stefanie; Rawlence, Nicolas J.; Anderson, Christian N. K.; Smith, Ian W. G.; Scofield, R. Paul; Waters, Jonathan M. (3 February 2016). "Invader or resident? Ancient-DNA reveals rapid species turnover in New Zealand little penguins". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 283 (1824): 20152879. doi:10.1098/rspb.2015.2879. PMC 4760177. PMID 26842575.

- Grosser, Stefanie. "NZ's southern little penguins are recent Aussie invaders: Otago research". University of Otago. University of Otago: Department of Zoology. Retrieved 11 May 2016.

- Grosser, Stefanie; Burridge, Christopher P.; Peucker, Amanda J.; Waters, Jonathan M. (14 December 2015). "Coalescent Modelling Suggests Recent Secondary-Contact of Cryptic Penguin Species". PLOS ONE. 10 (12): e0144966. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1044966G. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0144966. PMC 4682933. PMID 26675310.

- Baker AJ, Pereira SL, Haddrath OP, Edge KA (2006). "Multiple gene evidence for expansion of extant penguins out of Antarctica due to global cooling". Proc Biol Sci. 273 (1582): 11–17. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3260. PMC 1560011. PMID 16519228.

- Williams (The Penguins) p. 230

- Dann, Peter (2005). "Longevity in Little Penguins" (PDF). Marine Ornithology (33): 71–72. Retrieved 17 September 2012.

- "Birds of world significance: Babel Island Group, Tasmania". Atlas of Australian Birds. Birds Australia. Retrieved 29 November 2011.

- "BABY PENGUIN FOUND ON THE BEACH AT SOUTHPORT (Q.)". Australasian (Melbourne, Vic. : 1864 - 1946). 21 June 1924. p. 68. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "NEWS AND NOTES". Geraldton Guardian (WA : 1950 - 1954). 17 January 1952. p. 2. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "THREATENED SPECIES CONSERVATION ACT 1995". www.austlii.edu.au. Australasian Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "Little Penguin population in Sydney's North Harbor". NSW Government - Environment & Heritage. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- "About Montague". Montague Island NSW. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- LANGFORD, BEN (4 March 2015). "Seabirds thrive on restored Five Islands Nature Reserve". Illawarra Mercury. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Shoal Bay". Port Stephens Australia. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- laspinne. "port stephens". Little Penguin research. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Susskind, Anne (3 November 1985). "The Struggle for Bowen Island". The Canberra Times. Canberra, Australia. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- "THE CRUSOE OF WEDGE ISLAND". Saturday Journal (Adelaide, SA : 1923 - 1929). 5 January 1924. p. 3. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- Wiebkin, A. S. (2011) Conservation management priorities for little penguin populations in Gulf St Vincent. Report to Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2011/000188-1. SARDI Research Report Series No.588. 97pp.

- "Eudyptula minor". Atlas of Living Australia. Retrieved 26 July 2014.

- "Eudyptula minor - Little Penguin". Parks & Wildlife Service, Tasmania. Archived from the original on 15 March 2011. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- "About Little Penguins". penguinfoundation.org.au. Retrieved 20 June 2019.

- "Conservation and Research Strategy 2007" (PDF). stkildapenguins.com.au. Earthcare St Kilda. Retrieved 2 December 2014.

- "Eudyptula minor – Little Penguin". www.environment.gov.au. Australian government - Department of Environment. Retrieved 3 December 2014.

- "Visitor Information: About Penguin Island". www.penguinisland.com.au. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 27 July 2014.

- Smith, L. E.; Johnstone, R. E. (1987). "Corella - Seabird Islands No. 179" (PDF). Australian Bird Study Association inc. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

- Douglas, Alfred (1 April 1928). "The little blue penguin". Sunday Times. Perth, Western Australia. Retrieved 19 October 2015.

- "Albany Suspects Incendiarism ALBANY, Saturday". The Daily News. 1 January 1938. p. 7. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- "CHAPTER XII.—1841". The Inquirer and Commercial News. 11 November 1898. p. 4. Retrieved 7 November 2015.

- Rodríguez, A., Chiaradia, A., Wasiak, P., Renwick, L., and Dann, P.(2016) "Waddling on the Dark Side: Ambient Light Affects Attendance Behavior of Little Penguins." Journal of Biological Rhythms 31:194-204

- Saraux, Claire; Chiaradia, Andre; Salton, Marcus; Dann, Peter; Viblanc, Vincent A (2016). "Negative effects of wind speed on individual foraging performance and breeding success in little penguins" (PDF). Ecological Monographs. 86 (1): 61–77. doi:10.1890/14-2124.1. Retrieved 6 January 2017.

- "Band tells a story". Victor Harbour Times (SA : 1932 - 1986). 14 November 1984. p. 2. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Penguin's travels revealed". Times (Victor Harbor, SA : 1987 - 1999). 16 February 1996. p. 13. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Stahel, Colin; Gales, Rosemary (1987). Little Penguin - Fairy Penguins in Australia. New South Wales University Press. pp. 51–99.

- Flemming, S.A., Lalas, C., and van Heezik, Y. (2013) "Little penguin (Eudyptula minor) diet at three breeding colonies in New Zealand". New Zealand Journal of Ecology 37: 199–205 Accessed 30 January 2014.

- "Little Penguin Factsheet" Auckland Council, New Zealand (28 February 2014). Accessed 2014-07-26.

- Flemming, S.A. (2013) "". In Miskelly, C.M. (ed.) New Zealand Birds Online

- Chiaradia, A., Forero, M. G., Hobson, K. A., and Cullen, J. M. (2010) Changes in diet and trophic position of a top predator 10 years after a mass mortality of a key prey. – ICES Journal of Marine Science, 67: 1710–1720

- Christie Wilcox (15 September 2017). "Penguins Caught Feasting on an Unexpected Prey". National Geographic.

- Numata, M; Davis, L & Renner, M (2000) "[Prolonged foraging trips and egg desertion in little penguins (Eudyptula minor)]". New Zealand Journal of Zoology 27: 291-298

- Bethge, P; Nicol, S; Culik, BM & RP Wilson (1997) "Diving behaviour and energetics in breeding little penguins (Eudyptula minor)". Journal of Zoology 242: 483-502

- Ropert-Coudert Y, Chiaradia A, Kato A (2006) "An exceptionally deep dive by a Little Penguin Eudyptula minor". Marine Ornithology 34: 71-74

- Ashley Chung. "Eudyptula minor Little Penguin". Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- "About Little Penguins". penguinfoundation.org.au. Retrieved 3 April 2016.

- Wiebkin, A. S. (2011) Conservation management priorities for little penguin populations in Gulf St Vincent. Report to Adelaide and Mount Lofty Ranges Natural Resources Management Board. South Australian Research and Development Institute (Aquatic Sciences), Adelaide. SARDI Publication No. F2011/000188-1. SARDI Research Report Series No.588. 97pp

- Colombelli-Négrel, Diane; Tomo, Ikuko (2017). "Identification of terrestrial predators at two Little Penguin colonies in South Australia". Australian Field Ornithology. 34 (0).

- Penguins—Environment, South Australian Government Archived 20 October 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- Littlely, Bryan (10 October 2007). "Fur seals threat to Granite Island penguins". The Advertiser. p. 23.

- Preston, T. (1 December 2008). "Water rats as predators of little penguins". Victorian Naturalist. 125: 165–168.

- "Wild Nature's Ways". Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 - 1954). 5 March 1935. p. 17. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "BIG PENGUIN TOLL A MYSTERY". News (Adelaide, SA : 1923 - 1954). 19 March 1940. p. 13. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Letters to the Editor". Times (Victor Harbor, SA : 1987 - 1999). 24 November 1992. p. 9. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Elliot kids love penguins". Times (Victor Harbor, SA : 1987 - 1999). 17 November 1995. p. 14. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Hay, Alexander (24 September 1949). "Days of Misery on Barren Isle". The Mail. Adelaide, South Australia. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- "S.A. Pair Marooned on Barren Island". The Advertiser. Adelaide, South Australia. 19 September 1949. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- "Esperance news by telegraph. Loss of the Fleetwing". The Norseman Pioneer. 28 November 1896. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

- "STORY OF THE PENGUINS". Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1889 - 1931). 13 May 1899. p. 6. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "PORT POINTS". Sunday Times (Perth, WA : 1902 - 1954). 19 April 1903. p. 2. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "DESTRUCTION OF SEALS". Argus (Melbourne, Vic. : 1848 - 1957). 8 August 1941. p. 2. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "THE PORT LINCOLN RAILWAY". Chronicle (Adelaide, SA : 1895 - 1954). 10 September 1904. p. 30. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Taxidermist Cuts His Cloth To Suit The Times". Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 - 1954). 10 June 1939. p. 12. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Port Lincoln's Islands—Sir Joseph Bank's Group". Port Lincoln Times (SA : 1927 - 1954). 24 February 1939. p. 7. Retrieved 2 June 2020.

- Pim, Mr. (2 March 1951). "Passing By". News. Adelaide, South Australia. Retrieved 28 July 2014.

- Tourism Victoria. "Phillip Island Penguin Parade". Visit Victoria. Retrieved 21 July 2011.

- Stahel, Colin; Gales, Rosemary (1987). Little Penguin - Fairy Penguins in Australia. New South Wales University Press. p. 108.

- Tourism Tasmania > Bicheno Penguin Tours Accessed 16 September 2013.

- "Welcome". Low Head Penguin Tours. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- "Where to see little penguins in Tasmania". ABC News. 20 January 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

- "Penneshaw Penguin Centre". Tourkangarooisland.com.au. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "Granite Island Recreation & Nature Park : Penguin Tours South Australia". Graniteisland.com.au. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "Granite Island Penguin Centre : Looking after the Little Penguins of South Australia". Graniteisland.com.au. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "Oamaru Blue Penguin Colony". Penguins.co.nz. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "Blue Penguins Pukekura". Bluepenguins.co.nz. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- "MY NATURE DIARY". Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 - 1954). 14 July 1925. p. 6. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Penguins: No cause for alarm". Times (Victor Harbor, SA : 1987 - 1999). 2 May 1990. p. 5. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Dann, P.; Norman, F. I.; Cullen, J. M.; Neira, F. J.; Chiaradia, A. (2000). "Mortality and breeding failure of little penguins, Eudyptula minor, in Victoria 1995-96 following a widespread mortality of pilchards, Sardinops sagax". Marine and Freshwater Research. 51: 355–362.

- Ward, T. M.; Smart, J.; Ivey, A. (2017). Stock Assessment of Australian Sardine (Sardinops sagax) off South Australia 2017 (PDF). South Australia: SARDI.

- "Penguin deaths mystery". Times (Victor Harbor, SA : 1987 - 1999). 30 June 1995. p. 1. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "BBC - Science & Nature -Sea Life - Fact Files: Little/Fairy penguin". bbc. July 2005. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- "Fox thought to have killed nearly 30 penguins shot overnight". ABC News. Retrieved 27 June 2015.

- Penguin-spotting encouraged after predator attack wipes out Cape Northumberland colony ABC News, 3 February 2017. Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- Vieru, Tudor (7 January 2009). "Sheepdogs Guard Endangered Fairy Penguin Colony". Softpedia. Retrieved 25 November 2011.

- Wallis, Robert; King, Kristie; Wallis, Anne (2017). "The Little Penguin'Eudyptula minor'on Middle Island, Warrnambool, Victoria: An update on population size and predator management". Victorian Naturalist. 134 (2): 48–51.

- Holland, Malcolm (6 December 2010). "Seven penguins found dead at Manly". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- "Dogs kill penguins". The Canberra Times. 10 July 1984. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- "Penguins killed in dog attack". Sydney Morning Herald. 12 March 2003. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- Carter, Mahalia; Dadson, Manika (15 September 2019). "Tasmanian Government boosts fines for wildlife slaughter". ABC News. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Almost 60 penguins killed in suspected dog attack in Tasmania, months after similar incident - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". mobile.abc.net.au. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- Carson, Jonathan (3 September 2014). "DOC devastated by death of penguins". Nelson Mail. Retrieved 4 September 2014.

- "Penguin colony attacked". Victor Harbour Times (SA : 1932 - 1986). 12 August 1981. p. 1. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Mead, Thomas (5 November 2014). "Stoat suspected in Little blue penguin massacre". 3 News. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- "FOXES OF PHILLIP ISLAND". Australasian (Melbourne, Vic. : 1864 - 1946). 22 March 1924. p. 59. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Penguins are plentiful". Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 - 1954). 25 August 1953. p. 7. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Penguin slaughter". Times. 11 March 1994. p. 1. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- "Keeps on lookout for fox which killed 14 penguins at Melbourne Zoo". news. Retrieved 4 November 2015.

- "Traffic, fishermen have killed most of Bruny penguins". The Mercury. 9 June 1953. Retrieved 20 December 2015 – via Trove.

- "These penguins are doomed". Mail (Adelaide, SA : 1912 - 1954). 18 March 1950. p. 3. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Animals Make Splash in News". Age (Melbourne, Vic. : 1854 - 1954). 13 March 1950. p. 3. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "PENGUINS WILL BE SAFE". Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 - 1954). 22 March 1950. p. 4. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "PHILLIP ISLAND PENGUINS". Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 - 1954). 11 March 1950. p. 3. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Carmody, James (23 February 2018). "Fears marina project could 'finish off' WA's little penguin population". ABC News. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "MUTTONBIRD INDUSTRY. Damage by penguins". Advocate. 27 August 1930. Retrieved 20 December 2015 – via Trove.

- "Albany Suspects Incendiarism". Daily News (Perth, WA : 1882 - 1950). 1 January 1938. p. 7. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Penguins used as footballs". Advocate. 22 March 1949 – via Trove.

- "PENGUINS, SEAGULLS KILLED". Victor Harbour Times (SA : 1932 - 1986). 12 January 1973. p. 7. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Penguin 'put to sleep'". Victor Harbour Times (SA : 1932 - 1986). 17 August 1983. p. 16. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Tourists target penguins". Victor Harbour Times. 11 January 1994. Retrieved 17 August 2015 – via Trove.

- "Island security under review". Times. 25 June 1998. p. 1. Retrieved 17 August 2015.

- "Attack angers guides". Times (Victor Harbor, SA : 1987 - 1999). 28 May 1998. p. 6. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- Dobbin, Marika. "Violent attacks on St Kilda's little penguins". The Age. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- Lansdown, Sarah (25 June 2018). "Penalty for killing nine little penguins no deterrent: seabird expert". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- Zwartz, Henry (25 June 2018) Penguin killer Joshua Leigh Jeffrey avoids jail; bird group expresses 'extreme disappointment' at sentence, ABC News, Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- Gooch, Declan (15 October 2018) Tasmanian man who beat penguins to death has 'manifestly inadequate' sentence doubled, ABC News, Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 October 2018.

- "Penguins found dumped in bin in Tasmania, with public asked to help solve mystery - ABC News (Australian Broadcasting Corporation)". mobile.abc.net.au. Retrieved 18 October 2018.

- "Penguin found dead in net". Times (Victor Harbor, SA : 1987 - 1999). 17 November 1992. p. 1. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- O'Doherty, Fiona (10 September 2014). "Death of 25 fairy penguins found at Altona Beach renews calls for commercial fishing net ban in Port Phillip Bay". Hobsons Bay Leader. Retrieved 16 September 2014.

- "Destruction of penguins". Advocate. Burnie, Tasmania. 1 August 1947. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- "CRAYFISHING". The Kangaroo Island Courier. 6 January 1912. p. 6. Retrieved 5 July 2015.

- Thomson, Donald (17 February 1928). "STACK ISLAND The remains of aboriginal feasts, penguins and rabbits, unfrequented Bass Strait". The Mercury. Retrieved 20 December 2015 – via Trove.

- "Destruction of penguins". Advocate. 1 August 1947. Retrieved 20 December 2015 – via Trove.

- "Concern felt for penguins". Advocate. 12 June 1953. Retrieved 20 December 2015 – via Trove.

- "Concern at killing of penguins". The Mercury. Hobart, Tasmania. 12 June 1953. Retrieved 11 November 2014.

- Cannell, B.L.; Campbell, K.; Fitzgerald, L.; Lewis, J.A.; Baran, I.J.; Stephens, N.S. (2015). "Anthropogenic trauma is the most prevalent cause of mortality in Little Penguins (Eudyptula minor) in Perth, Western Australia". Emu. 116 (1): 52–61. doi:10.1071/MU15039.

- "Little Penguins". Penguin Pedia. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- "Shipping industry reflects on Iron Baron spill" ABC News (2005-07-10). Retrieved 2014-01-27.

- Backhouse, Matthew (28 December 2011). "Penguin reigns in battle for nation's hearts". New Zealand Herald. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- "Rena: Oil clean-up chemical worries Greenpeace". New Zealand Herald. 25 November 2011. Retrieved 28 March 2012.

- "Penguins still dying from slick oil". Canberra Times (ACT : 1926 - 1995). 27 May 1990. p. 3. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "A Naturalist's Jottings". Frankston and Somerville Standard (Vic. : 1921 - 1939). 14 August 1925. p. 7. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Discharge Of Oil From Ships Kills Sea Birds". Advertiser (Adelaide, SA : 1931 - 1954). 3 August 1934. p. 13. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Oil Kills Penquins". Northern Times (Carnarvon, WA : 1905 - 1952). 7 November 1940. p. 5. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "OIL ON BAY KILLS MANY PENGUINS". Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 - 1954). 16 July 1946. p. 5. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Penguin guard stands watch". Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 - 1954). 3 July 1954. p. 1. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Oil causing big toll of penguins on bayside". Herald (Melbourne, Vic. : 1861 - 1954). 7 July 1954. p. 9. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Perkins, Miki (23 April 2020). "As climate heats up, artificial burrows could help penguins stay cool". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 29 April 2020.

- Antarctica warm snap likely put Australian wildlife off-kilter in the following months ABC News, 9 May 2020. Retrieved 9 May 2020.

- "Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment". Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Western Australian Legislation - Wildlife Conservation Act 1950". www.legislation.wa.gov.au. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- Counsel, Office of Parliamentary, South Australian Legislation, Office of Parliamentary Counsel, retrieved 22 April 2020

- "WILDLIFE ACT 1975 - SECT 3 Definitions". classic.austlii.edu.au. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Protected Species Identification Guide for Victoria's Commercial Fishers" (PDF).

- "View - Tasmanian Legislation Online". www.legislation.tas.gov.au. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Little Penguin Monitoring and Protection Measures | Department of Primary Industries, Parks, Water and Environment, Tasmania". dpipwe.tas.gov.au. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Critical Habitat Declaration for the Little Penguins of Manly" (PDF).

- "Wildlife Act 1953 No 31 (as at 02 August 2019), Public Act Contents – New Zealand Legislation". legislation.govt.nz. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- "Penguin colony attacked". Victor Harbour Times (SA : 1932 - 1986). 12 August 1981. p. 1. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Dogs come to fairy penguins' rescue". Special Broadcasting Service. 5 January 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- Austin Ramzynov, Australia Deploys Sheepdogs to Save a Penguin Colony, New York Times (3 November 2015).

- Donnison, Jon (14 December 2015). "The dogs that protect little penguins". BBC News Online. Retrieved 14 December 2015.

- Jokic, Verica (29 July 2014). "How one oddball dog saved Middle Island's penguins". Bush Telegraph. ABC Radio National. Retrieved 30 July 2014.

- "Penguin murders prompt sniper aid". BBC. 16 July 2009. Retrieved 16 July 2009.

- Kidd, Jessica (30 May 2019). "New huts to save Sydney's penguin population". ABC News. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- LANGFORD, BEN (4 March 2015). "Seabirds thrive on restored Five Islands Nature Reserve". Illawarra Mercury. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Conservation: Five Islands Nature Reserve island restoration". NSW National Parks. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- "Big Island Little Penguin, Shearwater and Petrel Remediation". Port Kembla 2505. 2 March 2017. Retrieved 30 April 2020.

- Sea Life Sydney Aquarium

- "Little Blue Penguin" (PDF). Zoos South Australia. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "Little Penguin". Zoos Victoria. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "AdventureTrail" (PDF). National Zoo & Aquarium. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "Little Penguin". Perth Zoo. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "Australian Little Penguin". Taronga Conservation Society Australia. Retrieved 12 March 2014.

- "Little Penguins | SEA LIFE Sydney Aquarium". www.sydneyaquarium.com.au. Retrieved 23 April 2020.

- "Little Penguins". Ballarat Wildlife Park. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Mystery penguin deaths at Sea World". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 15 August 2012.

- Authorities find unknown toxin in Sea World Penguins Archived 13 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Sea World probes mysterious deaths Archived 13 February 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- Penguin deaths remain a mystery Archived 21 March 2008 at the Wayback Machine

- "Seaworld opens new haven for penguins". Brisbane Times. 8 March 2008. Retrieved 24 January 2019.

- National Aquarium of New Zealand > New Zealand Land Animals - Little Penguin Accessed 27 December 2014

- New England Aquarium > Animals and Exhibits > Little Blue Penguin Accessed 2 March 2014

- "Penguin Cove — Little Penguin Conservation Center". Louisville Zoo. 20 April 2016. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- "Little Penguins Make a Big Splash - Bronx Zoo". bronxzoo.com. Retrieved 21 April 2020.

- ""Tux" the Aussie Penguin". Linux Australia. Archived from the original on 7 May 2006. Retrieved 25 June 2006.

- "The Eudyptula Challenge".

- "FINA". Melbourne, 2007. Retrieved 12 June 2012.

- Protecting our Little Penguins (Victorian Government website) Archived 21 July 2008 at the Wayback Machine

Further reading

- Williams, Tony D. (1995). The Penguins. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854667-X.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Eudyptula minor |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eudyptula minor. |

- State of Penguins: Little (blue) penguin – detailed and current species account of (Eudyptula minor) in New Zealand

- Little penguins at the International Penguin Conservation

- Little penguin at PenguinWorld

- West Coast Penguin Trust (New Zealand)

- Philip Island Nature Park website

- Gould's The Birds of Australia plate

- Roscoe, R. "Little (Blue) Penguin". Photo Volcaniaca. Retrieved 13 April 2008.