African penguin

The African penguin (Spheniscus demersus), also known as the Cape penguin, and South African penguin, is a species of penguin confined to southern African waters. Like all extant penguins, it is flightless, with a streamlined body, and wings stiffened and flattened into flippers for a marine habitat. Adults weigh on average 2.2–3.5 kg (4.9–7.7 lb) and are 60–70 cm (24–28 in) tall. It has distinctive pink patches of skin above the eyes and a black facial mask; the body upperparts are black and sharply delineated from the white underparts, which are spotted and marked with a black band. The pink gland above their eyes helps them to cope with changing temperatures. When the temperature gets hotter, the body of the African penguin sends more blood to these glands to be cooled by the air surrounding it. This then causes the gland to turn a darker shade of pink.[2]

| African Penguin | |

|---|---|

| |

| At the Boulders Beach in Cape Town, South Africa | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Sphenisciformes |

| Family: | Spheniscidae |

| Genus: | Spheniscus |

| Species: | S. demersus |

| Binomial name | |

| Spheniscus demersus | |

| |

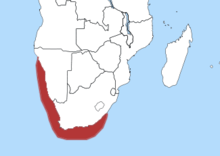

| Distribution of the African penguin | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Diomedea demersa Linnaeus, 1758 | |

The African penguin is a pursuit diver and feeds primarily on fish and squid. Once extremely numerous, the African penguin is declining rapidly due to a combination of several threats and is classified as endangered. It is a charismatic species and is popular with tourists. Other vernacular names of the species include black-footed penguin and jackass penguin, which it is called due to its loud donkey-like bray,[3] although several related species of South American penguins produce the same sound.

Taxonomy

The African penguin was one of the many bird species originally described by Linnaeus in the landmark 1758 10th edition of his Systema Naturae, where he grouped it with the wandering albatross on the basis of its bill and nostril morphology and gave it the name Diomedea demersa.[4]

The African penguin is a banded penguin, placed in the genus Spheniscus. The other banded penguins are the African penguin's closest relatives, and are all found mainly in the Southern Hemisphere: the Humboldt penguin and Magellanic penguins found in southern South America, and the Galápagos penguin found in the Pacific Ocean near the equator. All are similar in shape, colour and behaviour.

The African penguin is a member of the class Aves, and the order Sphenisciformes. It belongs to the penguin family Spheniscidae. It is classified as Spheniscus demersus. The genus to which the African penguin belongs, Spheniscus, derives from the Ancient Greek word sphen, which means wedge. This refers to their streamlined body shape. Its species name, demersus, is a Latin word for "plunging".[5]

Description

African penguins grow to 60–70 cm (24–28 in) tall and weigh between 2.2–3.5 kg (4.9–7.7 lb).[6] They have a black stripe and black spots on the chest, the pattern of spots being unique for every penguin, like human fingerprints. They have pink glands above their eyes, which are used for thermoregulation. The hotter the penguin gets, the more blood is sent to these glands so it may be cooled by the surrounding air, thus making the glands more pink.[7] This species exhibits slight sexual dimorphism: the males are slightly larger than the females and have longer beaks.[8] Juveniles do not possess the bold, delineated markings of the adult but instead have dark upperparts that vary from greyish-blue to brown; the pale underparts lack both spots and the band. The beak is more pointed than that of the Humboldt. Their distinctive black and white colouring is a vital form of camouflage called countershading– white for underwater predators looking upwards and black for predators looking down onto the dark water. African penguins look similar and are thought to be related to the Humboldt, Magellanic, and Galapagos penguins.[9] African penguins have a very recognisable appearance with a thick band of black that is in the shape of an upside-down horseshoe. They have black feet and unique black spots that vary in size and shape per penguin. Magellanic penguins share a similar characteristic that often confuses the two; Magellanics have a double bar on the throat and chest, whereas the African has a single bar. These penguins have the nickname of "jackass penguin" which comes from the loud noises they make.

Distribution and habitat

The African penguin is only found on the south-western coast of Africa, living in colonies on 24 islands between Namibia and Algoa Bay, near Port Elizabeth, South Africa.[1] It is the only penguin species that breeds in Africa and its presence gave name to the Penguin Islands.

Two colonies were established by penguins in the 1980s on the mainland near Cape Town, namely Boulders Beach near Simon's Town and Stony Point in Betty's Bay. Mainland colonies probably only became possible in recent times due to the reduction of predator numbers, although the Betty's Bay colony has been attacked by leopards.[10][11] The only other mainland colony is in Namibia, but it is not known when it was established.

Boulders Beach is a tourist attraction, for the beach, swimming and the penguins.[12][13] The penguins will allow people to approach them as close as a metre.

Breeding populations of African penguins are being kept in numerous zoos worldwide. No colonies are known outside the south-western coast of Africa, although vagrants (mostly juveniles) may occasionally be sighted beyond the normal range.

Population

Roughly 4 million penguins existed at the beginning of the 19th century. Of the 1.5-million population of African penguins estimated in 1910, only some 10% remained at the end of the 20th century. African penguin populations, which breed in Namibia and South Africa, have declined by 95 percent since pre-industrial times.[14]

Today, their breeding is largely restricted to 24 islands from Namibia to Algoa Bay, South Africa,[15] with the Boulders Beach colony being an exception to this rule.

The total population fell to approximately 150,000-180,000 in 2000.[16] Of those, 56,000 belonged to the Dassen Island colony and 14,000 to the Robben Island colony.[17] The colony at Dyer Island in South Africa fell from 46,000 in the early 1970s to 3,000 in 2008.[18]

In 2008, 5,000 breeding pairs were estimated to live in Namibia.

In 2010, the total African Penguin population was estimated at 55,000. At this rate of decline, the African penguin is expected to be extinct in the wild by 2026.[19]

In 2012, about 18,700 breeding pairs were estimated to live in South Africa, with the majority on St Croix Island in Algoa Bay.[1][20]

The total breeding population across both South Africa and Namibia fell to a historic low of about 20,850 pairs in 2019.[21]

Behaviour

Diet

African penguins forage in the open sea, where they pursue pelagic fish such as sardines and anchovies (e.g. Engraulis capensis),[22] and marine invertebrates such as squid and small crustaceans.[23] Penguins normally swim within 20 km of the shore.[6] A penguin may consume up to 540 grams of prey every day,[24] but this may increase to over 1 kg when raising older chicks.[23]

Due to the collapse of a commercial pilchard fishery in 1960, African penguin diet has shifted towards anchovies to some extent, although available pilchard biomass is still a notable determinant of penguin population development and breeding success. While a diet of anchovy appears to be generally sufficient, it is not ideal due to lower concentrations of fat and protein. Penguin diet changes throughout the year; as in many seabirds, it is believed that the interaction of diet choice and breeding success helps the penguins maintain their population size. Although parent penguins are protective of their hatchlings, they will not incur nutritional deficits themselves if prey is scarce and hunting requires greater time or energy commitment. This may lead to higher rates of brood loss under poor food conditions.

When foraging, African penguins carry out dives that on average reach a depth of 25 m and last for 69 s, although a maximum depth of 130 m and duration of 275 s has been recorded.[25]

Breeding

The African penguin is monogamous.[5] It breeds in colonies, and pairs return to the same site each year. The African penguin has an extended breeding season,[5] with nesting usually peaking from March to May in South Africa, and November and December in Namibia.[22] A clutch of two eggs are laid either in burrows dug in guano, or scrapes in the sand under boulders or bushes. Incubation is undertaken equally by both parents for around 40 days. At least one parent guards the chicks for about one month, whereafter the chicks joins a crèche with other chicks, and both parents head out to sea to forage each day.

Chicks fledge at 60 to 130 days, the timing depending on environmental factors such as the quality and availability of food. The fledged chicks then go to sea on their own, where they spend the next one to nearly two years. They then return to their natal colony to molt into adult plumage.[5]

When penguins molt, they are unable to forage as their new feathers are not yet waterproof; therefore, they fast over the entire molting period, which in African penguins takes around three weeks.[5]

Female African penguins remain fertile for 10 years. African penguins spend most of their lives at sea until it comes time for them to lay their eggs. Due to the high predation on the mainland, African penguins will seek protection on offshore islands, where they are safer from larger mammals and natural challenges. These penguins usually breed during the winter when temperatures are lower. African penguins often will abandon their eggs if they become overheated in the hot sun. Abandoned eggs do not survive the heat. Ideally, eggs are incubated in a burrow dug into the guano layer, which provides a suitable temperature regulation, but the widespread human removal of guano deposits has rendered this type of nest unfeasible at many colonies. To compensate, penguins dig holes in the sand, breed in the open, or make use of nest boxes if such are provided. The penguins spend three weeks on land to provide for their offspring, after which chicks may be left alone during the day while the parents forage. The chicks are frequently killed by predators or succumb to the hot sun. The eggs are three to four times bigger than hen's eggs. Parents usually feed hatchlings during dusk or dawn.

In 2015, when foraging conditions were favorable, more male than female African penguin chicks were produced in the colony on Bird Island. Male chicks also had higher growth rates and fledging mass, and therefore may have higher post-fledging survival than females. This coupled with higher adult female mortality in this species may result in a male biased adult sex ratio, indicating that conservation strategies focused on benefiting female African Penguins may be necessary.[26]

Predation

The average lifespan of an African penguin is 10 to 27 years in the wild, and up to 30 in captivity.[27]

Primary predators of African penguins include sharks and fur seals. While nesting, kelp gulls, mongooses, caracals, Cape genets and domestic cats may prey on the penguins and their chicks.[28][29] Pressure from terrestrial predators is higher if penguins are forced to breed in the open in the absence of suitable burrows or nest boxes.

Threats and conservation

Historical exploitation

African penguin eggs were considered a delicacy and were still being collected for sale as recently as the 1970s. In the 1950s, they were being collected from Dassen Island and sold in nearby towns.[30] In 1953, 12,000 eggs were collected.[31] In the late 1950s, some French chefs expressed interest in recipes for African penguin eggs collected from the islands off South Africa's west coast and placed annual orders for small quantities.[32][33][34] In the mid 1960s, eggs were collected in the thousands and sold by the dozen,[35] with each customer limited to two dozen eggs in total.[36]

The practice of collecting African penguin eggs involved smashing those found a few days prior to a collecting effort, to ensure that only freshly laid ones were sold. This added to the drastic decline of the African penguin population around the Cape coast, a decline which was hastened by the removal of guano from islands for use as fertiliser, eliminating the burrowing material used by penguins.[37]

Oil spills

Penguins remain susceptible to pollution of their habitat by petrochemicals from spills, shipwrecks and cleaning of tankers while at sea. Accounts of African penguins impacted by oil date back to the 1930s.[38] In 1953, dead penguins were among a range of birds, fish and other marine life that washed ashore dead after the tanker Sliedrecht was holed and spilled oil near Table Bay.[39] In 1971, the SS Wafra oil spill impacted the African penguin colony of Dyer Island. In 1975, newspapers reported that oil pollution from shipwrecks and the pumping of bilges at sea had killed tens of thousands of African penguins. At the time, the Dassen Island colony was being passed by 650 oil tankers each month.[40]

In 1979, an oil spill prompted the collection and treatment of 150 African penguins from St Croix Island near Port Elizabeth. The animals were later released at Robben Island and four of them promptly swam back to St Croix Island, surprising scientists.[41][42]

In 1983, the exposure of penguins of Dassen Island to the oil slick from the Castillo de Bellver was also a controversial topic at the time given their conservation status at the time, but owing to prevailing wind and current, only gannets were oiled.[43]

1994 MV Apollo Sea disaster

African penguin casualties were significant following the sinking of the MV Apollo Sea and subsequent oil slick in 1994. 10,000 penguins were collected and cleaned, of which less than half survived.[44]

2000 MV Treasure crisis

Disaster struck on 23 June 2000, when the iron ore tanker MV Treasure sank between Robben Island and Dassen Island, South Africa. It released 1,300 tons of fuel oil, causing an unprecedented coastal bird crisis,[45] oiling 19,000 adult penguins at the height of the best breeding season on record for this vulnerable species. The oiled birds were brought to an abandoned train repair warehouse in Cape Town to be cared for. An additional 19,500 un-oiled penguins were removed from Dassen Island and other areas before they became oiled, and were released about 800 kilometres east of Cape Town, near Port Elizabeth. This gave workers enough time to clean up the oiled waters and shores before the birds could complete their long swim home (which took the penguins between one and three weeks). Some of the penguins were named and radio-tracked as they swam back to their breeding grounds. Tens of thousands of volunteers helped with the rescue and rehabilitation process, which was overseen by IFAW (International Fund for Animal Welfare) and the South African Foundation for the Conservation of Coastal Birds (SANCCOB), and took more than three months to complete. This was the largest animal rescue event in history; more than 91% of the penguins were successfully rehabilitated and released – an amazing feat that could not have been accomplished without such a tremendous international response.[46]

Due to the positive outcome of African penguins being raised in captivity after tragedies, such as the Treasure oil spill, the species is considered a good "candidate for a captive-breeding programme which aims to release offspring into the wild"; however, worries about the spread of new strains of avian malaria is a major concerning factor in the situation.[47]

Bringing the birds inland led to the exposure of parasites and vector species such as mosquitoes, specifically avian malaria which has caused 27% of the rehabilitated penguins deaths annually.[48]

2016 & 2019 Port of Ngqura

Small scale oil spills (of less than 400 litres) have occurred at the Port of Nqgura since bunkering activities started there in 2016. Bunkering is a ship refueling process that can result in oil spills and slicks entering the water. Hundreds of African penguins have been harmed following these spills,[49] due to the port's close proximity to penguin rookeries on St. Croix Island and seabird habitat on neighbouring Jahleel and Brenton Islands.

Competition with fisheries

Commercial fisheries of sardines and anchovy, which constitute the two main prey species of the penguins, have forced these penguins to search for prey farther off shore, as well as having to switch to eat less nutritious prey.[14] Experimental closures of the immediate vicinity of colony sites at e.g. Robben Island to fishery for short periods (3 years) were shown to result in marked benefits to penguin breeding success, and longer closure periods and their extension to further colonies are being evaluated.[50][51][52]

Conservation status

The African penguin is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African–Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds (AEWA) applies. In November 2013 the African penguin was listed as endangered on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species.[1] In September 2010 it was listed as endangered under the US Endangered Species Act.[14]

Mediation efforts

Many organisations such as SANCCOB, Dyer Island Conservation Trust, SAMREC and Raggy Charters with the Penguin Research Fund in Port Elizabeth are working to halt the decline of the African penguin. Measures include monitoring population trends, hand-rearing and releasing abandoned chicks, establishing artificial nests and proclaiming marine reserves in which fishing is prohibited.[1] Some colonies (e.g. on Dyer Island) are suspected to be under heavy pressure from predation by Cape fur seals and may benefit from the culling of individual problem animals[51][53] which has been found effective (although requiring a large amount of management effort) in trials.[54]

Established in 1968, SANCCOB is currently the only organisation mandated by the South African government to respond to crises involving seabirds along South Africa's coastline and is internationally recognised for the role it played during the MV Treasure oil spill when more than 20,000 African penguins were oiled when the ship sank between Robben Island and Dassen Island. A modeling exercise conducted in 2003 by the University of Cape Town's Percy Fitz Patrick Institute of African Ornithology found that rehabilitating oiled African penguins has resulted in the current population being 19 percent larger than it would have been in the absence of SANCCOB's rehabilitation efforts.[55]

In February 2015, the Dyer Island Conservation Trust opened the African Penguin and Seabird Sanctuary (APSS) in Gansbaai, South Africa.[56] The centre was opened by the Department of Tourism Minister Derek Hanekom [57] and will serve as a hub for seabird research carried out by the Dyer Island Conservation Trust. The centre will also run local education projects, host international marine volunteers, and seek to improve seabird handling techniques and rehabilitation protocols.

Captivity

.jpg)

African penguins are a commonly seen species in zoos across the world. Because they do not require particularly low temperatures, they are often kept in outside enclosures. They adapt fairly well to this captive environment and are rather easy to breed compared to other species of the family. In Europe the breeding program or EEP is regulated by Artis zoo in the Netherlands, whilst in the United States the SSP is coordinated by Smithsonian National Zoological Park. The idea is to create a backup ex-situ population, as well as to aid in the conservation of the in-situ population. Between 2010 and 2013, American zoos spent $300 000 on in-situ conservation.[58][59]

Gallery

Nesting African penguin.

Nesting African penguin. Colony of African penguins nesting on Boulders Beach in Cape Town.

Colony of African penguins nesting on Boulders Beach in Cape Town. African penguins on Boulders Beach.

African penguins on Boulders Beach. African penguins on a rock at Boulders Beach.

African penguins on a rock at Boulders Beach.

References

- BirdLife International (2018). Spheniscus demersus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2018. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2018-2.RLTS.T22697810A132604504.en

- a-z animals. "The African Penguin". a-z animals. Retrieved 2013-07-09.

- Favaro, Livio; Ozella, Laura; Pessani, Daniela; Pavan, Gianni (30 July 2014). "The Vocal Repertoire of the African Penguin (Spheniscus demersus): Structure and Function of Calls". PLoS ONE. 9 (7): e103460. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0103460. PMC 4116197. PMID 25076136.

- Linnaeus, Carl (1758). Systema Naturae per Regna Tria Naturae, Secundum Classes, Ordines, Genera, Species, cum Characteribus, Differentiis, Synonymis, Locis. Tomus I. Editio decima, reformata (in Latin). Holmiae: (Laurentii Salvii). p. 132.

- Penguins: African Penguins – Spheniscus demersus. Penguins.cl. Retrieved on 2015-09-25.

- Sinclair, Ian; Hockey, Phil; Tarboton, Warwick; Ryan, Peter (2011). Sasol Birds Of South Africa. Struik. p. 22. ISBN 9781770079250.

- Mahard, Tyler (2012). "The Black-footed Penguin Spheniscus demersus". Wildlife Monthly. Retrieved 2012-11-20.

- "African Penguin (Speheniscus demersus)". Dyer Island Conservation Trust. Archived from the original on 26 October 2009.

- "African Penguin". Retrieved 2013-01-30.

- "The African Penguin". Bettysbay.info. 2010-04-08. Archived from the original on May 30, 2012. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- CapeNature increases protection from predators at Stony Point. capenature.co.za

- "Table Mountain National Park". SANParks. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- "Boulders Beach, Swimming with Penguins – Swimming with Penguins in South Africa". Goafrica.about.com. 2010-06-14. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- Kilduff, Catherine (September 28, 2010) Vanishing African Penguin, Threatened by Climate Change and Fishing, Wins Protections. seaturtles.org

- "Know your Georgia Aquarium penguins (2006)". The Atlanta Constitution. 2006-11-17. pp. G6. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Penguins begin swim home (Treasure, 2000)". York Daily Record. 2000-10-12. p. 6. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Flight of the African penguin (2000)". Tampa Bay Times. 2000-07-08. p. 2. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Experiments seek to house declining South African penguins (2009)". The Boston Globe. 2009-03-30. pp. A6. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "African Penguin | Endangered | Cape Town". Globalpost.com. 2011-06-19. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- Makhado, A.B., B.N. Dyer, R. Fox, D. Geldenhuys, L. Pichegru, R.M. Randall, R.B. Sherley, L. Upfold, J. Visagie., L.J. Waller, P.A. Whittington, and R.J.M. Crawford. 2013. Estimates of numbers of twelve seabird species breeding in South Africa, updated to include 2012. Branch Oceans and Coasts, Department of Environmental Affairs, Cape Town.

- Sherley, R.B.; Crawford, R.J.; de Blocq, A.D.; Dyer, B.M.; Geldenhuys, D.; Hagen, C.; Kemper, J.; Makhado, A.B.; Pichegru, L.; Upfold, L.; Visagie, J.; Waller, Lauren J.; Winker, Henning (2020). "The conservation status and population decline of the African penguin deconstructed in space and time". bioRxiv. doi:10.1101/2020.01.15.907485.

- "African penguin videos, photos and facts – Spheniscus demersus". ARKive. Archived from the original on 2012-03-22. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- "The African Penguin Simons Town". Simonstown.com. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- Crawford, R. J. M.; Ryan, P. G.; Williams, A. J. (1991). "Seabird consumption and production in the Benguela and western Agulhas ecosystems". South African Journal of Marine Science. 11 (1): 357–375. doi:10.2989/025776191784287709.

- Ropert-Coudert Y, Kato A, Robbins A, Humphries GRW (October 2018). "African Penguin (Spheniscus demersus)". The Penguiness book, version 3.0. Unpublished. doi:10.13140/RG.2.2.32289.66406.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Spelt, A.; Pichegru, L. (2017). "Sex allocation and sex-specific parental investment in an endangered seabird". Ibis. 159 (2): 272–284. doi:10.1111/ibi.12457.

- "ADW: Spheniscus demersus: INFORMATION". Animaldiversity.ummz.umich.edu. 2010-02-01. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- Whittington, P. A.; Hofmeyr, J. H.; Cooper, J. (1996). "Establishment, growth and conservation of a mainland colony of Jackass Penguins Spheniscus demersus at Stony Point, Betty's Bay, South Africa". Ostrich. 67 (3–4)): 144–150. doi:10.1080/00306525.1996.9639700.

- "African penguin". Neaq.org. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- "Dassen Island African penguins (1955)". The Pantagraph. 1955-01-09. p. 10. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Penguin playmates & egg exports, Dassen Island (1954)". Press and Sun-Bulletin. 1954-10-23. p. 4. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "French Gourmet Finds Penguin Egg Recipes (1959)". The Racine Journal-Times Sunday Bulletin. 1959-08-09. p. 17. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Penguin-egg eating may spread (1959)". The Troy Record. 1956-07-23. p. 14. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Penguin eggs sent to French eaters (1959)". The Daily Oklahoman. 1959-05-24. p. 48. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Penguins' Eggs Again To Grace Gourmets' Tables (1965)". Arizona Daily Star. 1965-05-30. p. 32. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Must Ration Penguin Eggs at $2.10 a Dozen (1965)". Sioux City Journal. 1965-05-09. p. 49. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- Shannon, L. J.; Crawford, R. J. M. (1999). "Management of the African penguin Spheniscus demersus — insights from modelling". Marine Ornithology. 27: 119–128.

- "Oily penguin, South Africa (1936)". Hartford Courant. 1936-08-02. p. 70. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Ship Oil Kills Fish, Penguins". Newcastle Sun (NSW : 1918 - 1954). 1953-11-03. p. 8. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "South Africa's penguins die from oil pollution effects (1975)". Arizona Republic. 1975-05-01. p. 1. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- ""Homing" Penguins Travel 500 Miles (1979)". The Charlotte News. 1979-09-17. p. 4. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Penguins baffle scientists (1979)". The Daily News. 1979-09-18. p. 27. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- "Split Supertanker Gets Slow Tow Out To Sea (Castillo de Bellver oil spill, 1983)". The Baytown Sun. 1983-08-08. p. 6. Retrieved 2020-05-09.

- Wolfaardt, A. C.; Underhill, L. G.; Altwegg, R.; Visagie, J. (2008). "Restoration of oiled African penguins Spheniscus demersus a decade after the Apollo Sea spill". African Journal of Marine Science. 30 (2): 421–436. doi:10.2989/ajms.2008.30.2.14.564.

- Penguins, rescue, rehabilitation, research, internships. Sanccob. Retrieved on 2015-09-25.

- ""Jackass Penguins Freed after Rehab", National Geographic's Video News, June 17, 2009". News.nationalgeographic.com. 2010-10-28. Retrieved 2012-03-30.

- Barham, P. J.; L. G. Underhill; R. J. M. Crawford; R. Altewegg; T. M. Leshoro; D. A. Bolton; B. M. Dyer & L. Upfold (2008). "The efficacy of hand-rearing penguin chicks: evidence from African penguins (Spheniscus demersus) orphaned in the Treasure oil spill". Bird Conservation International. 18 (2). doi:10.1017/S0959270908000142.

- Grim, C. (2003). "Plasmodium juxtanucleare associated with mortality in black-footed penguins (Spheniscus demersus) admitted to a rehabilitation center". Journal of Zoo and Wildlife Medicine. 34 (3): 250–5. doi:10.1638/02-070. JSTOR 20460327. PMID 14582786.

- "Refuelling under scrutiny as S.Africa penguins hit by oil spill". phys.org. Retrieved 2020-04-23.

- Sherley, R. B.; Underhill, L. G.; Barham, B. J.; Barham, P. J.; Coetzee, J. C.; Crawford, R. J.; Dyer, B. M.; Leshoro, T. M.; Upfold, L. (2013). "Influence of local and regional prey availability on breeding performance of African penguins Spheniscus demersus". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 473: 291–301. Bibcode:2013MEPS..473..291S. doi:10.3354/meps10070.

- Weller, Florian; Sherley, Richard B.; Waller, Lauren J.; Ludynia, Katrin; Geldenhuys, Deon; Shannon, Lynne J.; Jarre, Astrid (2016). "System dynamics modelling of the Endangered African penguin populations on Dyer and Robben islands, South Africa". Ecological Modelling. 327: 44–56. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2016.01.011.

- Sherley, Richard B.; et al. (2018). "Bayesian inference reveals positive but subtle effects of experimental fishery closures on marine predator demographics". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 285 (1871): 20172443. doi:10.1098/rspb.2017.2443. PMC 5805942. PMID 29343602.

- Ludynia, K.; L.J. Waller; R.B. Sherley; F. Abadi; Y. Galada; D. Geldenhuys; R.J.M Crawford; L.J. Shannon & A. Jarre (2014). "Processes influencing the population dynamics and conservation of African penguins on Dyer Island, South Africa". African Journal of Marine Science. 36 (2): 253. doi:10.2989/1814232X.2014.929027.

- Makhado, A.B.; M.A. Meÿer; R.J.M. Crawford; L.G Underhill & C. Wilke (2009). "The efficacy of culling seals seen preying on seabirds as a means of reducing seabird mortality". African Journal of Ecology. 47 (3): 335. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2028.2008.00966.x. hdl:11427/24160.

- Nel, D. C.; Crawford, R. J. M.; Parsons, N. J. (2003). "The conservation status and impact of oiling on the African penguin". In Nel, D. C.; Whittington, P. A. (eds.). Rehabilitation of Oiled African Penguins: a Conservation Success Story. Cape Town: BirdLife South Africa and Avian Demography Unit. pp. 1–7.

- ""FIRST CLASS AFRICAN PENGUIN AND SEABIRD SANCTUARY OPENS IN KLEINBAAI, OVERBERG", ScenicSouth, February 26, 2015". SceinicSouth.co.za. 2015-02-26. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- ""Rehab center goes to the birds", iol SciTech, March 3, 2015". iol.co.za. 2015-03-03. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- "African Penguin". aza.org.

- "Nature conservation project African penguin". artis.nl.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to: |

| Wikispecies has information related to Spheniscus demersus |

- California Academy of Sciences: Web cams, mobile app and blog

- ARKive there are African penguins – Images and movies of the African penguin

- African penguins from the International Penguin Conservation website

- "Toronto Zoo | African Penguins –

- Dyer Island Conservation Trust

- African Penguin and Seabird Sanctuary

- African penguins on Boulders beach south of Cape Town