Lakhmids

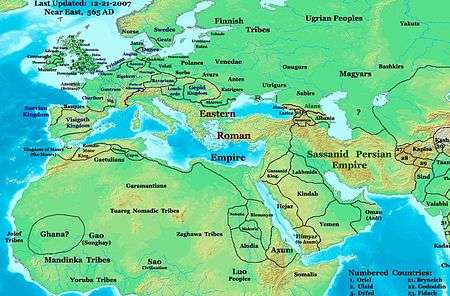

The Lakhmids (Arabic: اللخميون) referred to in Arabic as al-Manādhirah (المناذرة) or Banu Lakhm (بنو لخم) were an Arab kingdom of southern Iraq with al-Hirah as their capital, from about 300 to 602 AD. They were generally but intermittently the allies and clients of the Sassanian Empire, and participant in the Roman–Persian Wars. While the term "Lakhmids" has also been applied to the ruling dynasty, more recent scholarship prefers to refer to the latter as the Naṣrids.[1]

Lakhmid Kingdom المناذرة | |

|---|---|

| c.300–602 | |

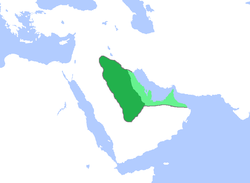

Map of the Lakhmid kingdom in the 6th-century. Light green is Sasanian territory governed by the Lakhmids. | |

| Capital | Al-Hirah |

| Common languages | |

| Religion | Arab Paganism Manichaeism Christianity (Church of the East) |

| Government | Monarchy |

| History | |

• Established | c.300 |

• Annexed by Sasanian Empire | 602 |

Nomenclature and problems of Lakhmid history

The nature and identity of the Lakhmid kingdom remains mostly unclear. The ruling Nasrid family emerges with "Amr of the Lakhm", mentioned in the late 3rd-century Paikuli inscription among the vassals of the Sasanian Empire. From this, the term "Lakhmid" has been applied by historians to the Nasrids and their subjects, ruled from al-Hirah. However, as historian Greg Fisher points out, there is "very little information about who made up the people who lived in or around al-Hirah, and there is no reason to suppose that any connection between Nasrid leaders and Lakhm that may have existed in the third century was still present in the sixth, or that the Nasrids ruled over a homogeneous Lakhmid kingdom".[1] This situation is exacerbated by the fact that the historical sources—mostly Byzantine—start dealing with the Lakhmids in greater detail only from the late 5th century, as well as by the relative lack of archaeological work at al-Hirah.[2]

History

The Lakhmid Kingdom was founded and ruled by the Banu Lakhm tribe that emigrated from Yemen in the second century. The founder of the dynasty was 'Amr, whose son Imru' al-Qais (not to be confused with the poet Imru' al-Qais who lived in the sixth century) is claimed to have converted to Christianity. However, there is debate on his religious affinity. Theodor Nöldeke noted that Imru' al-Qays ibn 'Amr was not a Christian,[3] while Irfan Shahîd noted a possible Christian affiliation, suggesting that Imru'al Qays' Christianity may have been "orthodox, heretical or of the Manichaean type".[4] Furthermore, Shahid asserts that the funerary inscription of Imru' al Qays ibn 'Amr lacks Christian formulas and symbols.[5]

Imru' al-Qais dreamt of a unified and independent Arab kingdom and, following that dream, he seized many cities in the Arabian Peninsula. He then formed a large army and developed the Kingdom as a naval power, which consisted of a fleet of ships operating along the Bahraini coast. From this position he attacked the coastal cities of Iran - which at that time was in civil war, due to a dispute as to the succession - even raiding the birthplace of the Sasanian kings, Fars Province.

In 325, the Persians, led by Shapur II, began a campaign against the Arab kingdoms. When Imru' al-Qais realised that a mighty Persian army composed of 60,000 warriors was approaching his kingdom, he asked for the assistance of the Roman Empire. Constantine promised to assist him but was unable to provide that help when it was needed. The Persians advanced toward Hira and a series of vicious battles took place around and in Hira and the surrounding cities.

Shapur II's army defeated the Lakhmid army and captured Hira. In this, the young Shapur acted much more violently and slaughtered all the Arab men of the city and took the Arab woman and children as slaves. He then installed Aws ibn Qallam and retreated his army.

Imru' al-Qais escaped to Bahrain, taking his dream of a unified Arab nation with him, and then to Syria seeking the promised assistance from Constantius II which never materialized, so he stayed there until he died. When he died he was entombed at al-Nimarah in the Syrian desert.

Imru' al-Qais' funerary inscription is written in an extremely difficult type of script. Recently there has been a revival of interest in the inscription, and controversy has arisen over its precise implications. It is now certain that Imru' al-Qais claimed the title "King of all the Arabs" and also claimed in the inscription to have campaigned successfully over the entire north and centre of the peninsula, as far as the border of Najran.

Two years after his death, in the year 330, a revolt took place where Aws ibn Qallam was killed and succeeded by the son of Imru' al-Qais, 'Amr. Thereafter, the Lakhmids' main rivals were the Ghassanids, who were vassals of the Sassanians' arch-enemy, the Roman Empire. The Lakhmid kingdom could have been a major centre of the Church of the East, which was nurtured by the Sassanians, as it opposed the Chalcedonian Christianity of the Romans.

The Lakhmids remained influential throughout the sixth century. Nevertheless, in 602, the last Lakhmid king, al-Nu'man III ibn al-Mundhir, was put to death by the Sasanian emperor Khosrow II because of a false suspicion of treason, and the Lakhmid kingdom was annexed.

It is now widely believed that the annexation of the Lakhmid kingdom was one of the main factors behind the fall of the Sasanian Empire and the Muslim conquest of Persia as the Sassanians were defeated in the Battle of Hira by Khalid ibn al-Walid.[6] At that point, the city was abandoned and its materials were used to reconstruct Kufa, its exhausted twin city.

According to the Arab historian Abu ʿUbaidah (d. 824), Khosrow II was angry with the king, al-Nu'man III ibn al-Mundhir, for refusing to give him his daughter in marriage, and therefore imprisoned him. Subsequently, Khosrow sent troops to recover the Nu'man family armor, but Hani ibn Mas'ud (Nu'man's friend) refused, and the Arab forces of the Sasanian Empire were annihilated at the Battle of Dhi Qar, near al-Hirah, the capital of the Lakhmids, in 609. Hira stood just south of what is now the Iraqi city of Kufa.

Lakhmid dynasty and its descendants

| Historical Arab states and dynasties | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Ancient Arab States

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arab Empires

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Eastern Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Western Dynasties

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Arabian Peninsula

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

East Africa

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Current monarchies

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The founder and most of the rulers of the kingdom were from the Banu Lakhm dynasty.

Many modern "Qahtanite" dynasties claim descent from the Lakhmids such as the Mandharis of Oman, Iraq, and the United Arab Emirates, the Na'amanis of Oman, and the Druze Arslan royal family.

Lakhmid rulers

| # | Ruler | Reign |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 'Amr I ibn Adi | 268–295 |

| 2 | Imru' al-Qays I ibn 'Amr | 295–328 |

| 3 | 'Amr II ibn Imru' al-Qays | 328–363 |

| 4 | Aws ibn Qallam (non-dynastic) | 363–368 |

| 5 | Imru' al-Qays II ibn 'Amr | 368–390 |

| 6 | al-Nu'man I ibn Imru' al-Qays | 390–418 |

| 7 | al-Mundhir I ibn al-Nu'man | 418–462 |

| 8 | al-Aswad ibn al-Mundhir | 462–490 |

| 9 | al-Mundhir II ibn al-Mundhir | 490–497 |

| 10 | al-Nu'man II ibn al-Aswad | 497–503 |

| 11 | Abu Ya'fur ibn Alqama (non-dynastic, uncertain) | 503–505 |

| 12 | al-Mundhir III ibn al-Nu'man | 503/5–554 |

| 13 | 'Amr III ibn al-Mundhir | 554–569 |

| 14 | Qabus ibn al-Mundhir | 569–573 |

| 15 | Suhrab (Persian governor) | 573–574 |

| 16 | al-Mundhir IV ibn al-Mundhir | 574–580 |

| 17 | al-Nu'man III ibn al-Mundhir | 580–602 |

| 18 | Iyas ibn Qabisah al-Ta'i (non-dynastic) with Nakhiragan (Persian governor) | 602–617/618 |

| 19 | Azadbeh (Persian governor) followed by the Muslim conquest of Persia | 617/618–633 |

Abbadid dynasty

The Abbadid dynasty, which ruled the Taifa of Seville in al-Andalus in the 11th century, was of Lakhmid descent.[7]

In literature

Poets described al-Hira as paradise on earth; an Arab poet described the city's pleasant climate and beauty thus: "One day in al-Hirah is better than a year of treatment". The ruins of al-Hirah are located 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) south of Kufa on the west bank of the Euphrates.

See also

- Kingdom of Araba

- Tanukhids

- Christian Arabs

References

- Fisher 2011, p. 258.

- Fisher 2011, pp. 258–259.

- Nöldeke, Theodor. Geschichte der Perser und Araber zur Zeit der Sasaniden. p. 47.

- Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fourth Century, Irfan Shahid. pp. 33–34. Imru'al-qays christianity (may have been) orthodox, heretical or of the manichaean type [...] Perhaps Imru' al-Qays christianity was of the manichaean type, completely unacceptable to those in Byzantium. His father 'Amr was the protector of Manichaeism in Hira, that followed the crucifixion of Mani, the coptic papyri have shown.

- Byzantium and the Arabs in the Fourth Century, Irfan Shahîd. p. 32. .Allthough Imru' al-Qays was considered christian [...] there is not a single christian formula or symbol in the (Namarah) inscription.

- Iraq After the Muslim Conquest By Michael G. Morony, pg. 233

- Soravia, Bruna (2011). "ʿAbbādids". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Brill Online. ISSN 1873-9830.

Sources

- Bosworth, C. E. (1983). "Iran and the Arabs Before Islam". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). The Cambridge History of Iran: The Seleucid, Parthian, and Sasanian periods (1). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 593–612. ISBN 978-0-521-200929.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bosworth, C.E., ed. (1999). The History of al-Ṭabarī, Volume V: The Sāsānids, the Byzantines, the Lakhmids, and Yemen. SUNY Series in Near Eastern Studies. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press. pp. 370–371. ISBN 978-0-7914-4355-2.

- Fisher, Greg (2011). "Kingdoms or Dynasties? Arabs, History, and Identity before Islam". Journal of Late Antiquity. 4 (2): 245–267. doi:10.1353/jla.2011.0024.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Martindale, John R., ed. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire: Volume III, AD 527–641. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-20160-8.

- History of the kings of Hirah, in The Fields of Gold by Al-Masudi (ca. 896–956), Abu al-Ḥasan ʿAlī ibn al-Ḥusayn ibn ʿAlī (1871) [1861], "44", Kitab Muruj adh-Dhahab wa-Ma'adin al-Jawhar (Les Prairies d'or), III, translated by de Meynard, Charles Barbier; de Courteille, Pavet, Paris: Imprimerie imperiale, pp. 181–213

- Rothstein, Gustav (1899). Die Dynastie der Lahmiden in al-Hîra. Ein Versuch zur arabisch-persichen Geschichte zur Zeit der Sasaniden [The Dynasty of the Lakhmids at al-Hira. An Essay on Arab–Persian History at the Time of the Sasanids] (in German). Berlin: Reuther & Reichard.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Britannica Encyclopedia

- Bahrain government website "Arabic website"

- Article about al-Hira history "Arabic website"

External links

- Al Sejel el Arslaneh (the book of the history of the Arslan dynasty)