Altıntaş, Midyat

Altıntaş (Classical Syriac: ܟܦܪܙܗ, romanized: Kfarze,[1][nb 1] Kurdish: Kevirzê)[5] is a village in Mardin Province in southeastern Turkey. It is located in the district of Midyat and the historical region of Tur Abdin.

Altıntaş | |

|---|---|

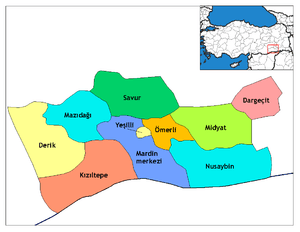

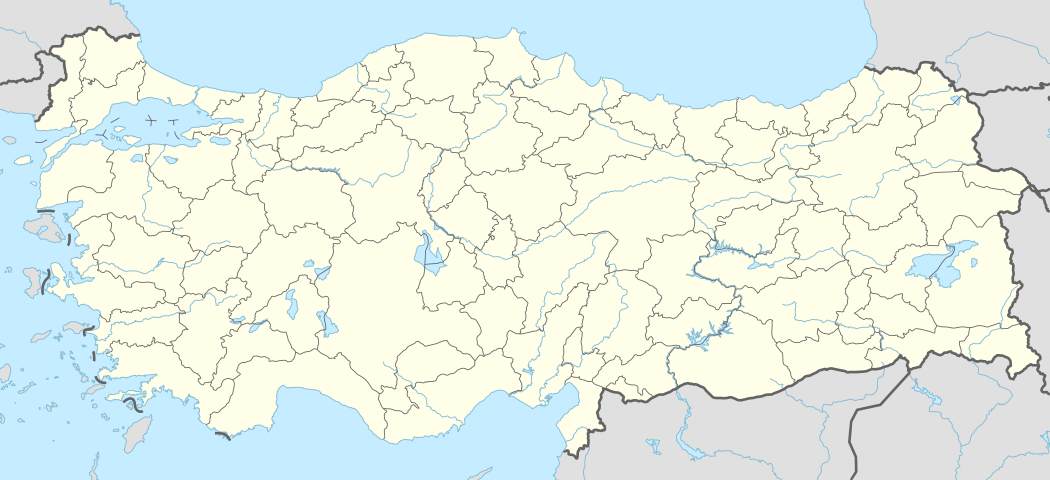

Altıntaş Location in Turkey | |

| Coordinates: 37.444°N 41.527°E | |

| Country | |

| Province | Mardin Province |

| District | Midyat |

| Population (2013) | |

| • Total | 275 |

In the village, there are churches of Yoldath Aloho, Mor Yohannon, Mor Abrohom, and Mor Izozoel.[6] There is also the ruins of the churches of Mor Eliyo and Mor Malke.[7]

Etymology

The Turkish name of the village comprises two words, "altın" ("gold" in Turkish) and "taş" ("stone" in Turkish), therefore Altıntaş translates to "gold stone".[4] The Syriac name of the village is derived from "kfar" ("village" in Syriac).

History

It was alleged that the church of Kfarze was constructed by Emperor Anastasius I Dicorus, however, this was fabricated to add historicity.[8] The Church of Mor Izozoel in Kfarze was likely constructed in the late 7th century AD.[6] The village is first mentioned in 935 AD, and was looted by Yazidis and Kurds in c. 1413.[7] Kfarze was attacked in 1855 by Prince Asdin Schin Buqtoyo and resulted in the death of many Christians.[7] Gertrude Bell visited the village in 1909 and 1911.[6]

In 1914, Kfarze was inhabited by approximately 160 Syriac Orthodox Christian families and 70 Muslim families.[9] During the Assyrian Genocide, upon receiving news of an impending Kurdish attack, most of the village's Assyrian population fled to Inwardo whilst those who remained were killed.[10] The Assyrians later returned to Kfarze in 1922.[10] Part of the nave vault of the Church of Mor Izozoel collapsed during the First World War or immediately after, and was restored in 1936.[4]

Kurds of Kfarze belong to the Dermemikan clan, and the village acts as the centre of the tribe.[11] The Kurdish poet Şivan Perwer is a descendant of the Muslim population of Kfarze.[11] In 2005, the village was populated by 12 Syriac Orthodox Christian families and 35-40 Kurdish families.[12] The Syriac Orthodox Christian population of Kfarze speak Turoyo.[7]

References

Notes

Citations

- Kfarze. The Syriac Gazeteer.

- Biner (2019), p. x

- "Bu köylerin isimleri değişecek!". Sözcü (in Turkish). 14 February 2015. Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- Sinclair (1989), p. 246

- Sediyani (2009), p. 255

- Sinclair (1989), p. 248

- Geschichte von Keferze. Keferze. (in German)

- Palmer (1990), p. 52

- Gaunt et al. (2006), p. 234

- Kfarze. Foundation for Conservation and Promotion of the Aramaic Cultural Heritage. (in German)

- Altıntaş. Index Anatolicus. (in Turkish)

- Csató et al. (2005), p. 182

Bibliography

- Biner, Zerrin Ozlem (2019). States of Dispossession: Violence and Precarious Coexistence in Southeast Turkey. University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Csató, Éva Ágnes; Isaksson, Bo; Jahani, Carina (2005). Linguistic Convergence and Areal Diffusion: Case Studies from Iranian, Semitic and Turkic. Psychology Press.

- Gaunt, David; Bet̲-Şawoce, Jan; Donef, Racho (2006). Massacres, Resistance, Protectors: Muslim-Christian Relations in Eastern Anatolia During World War I. Gorgias Press.

- Palmer, Andrew (1990). Monk and Mason on the Tigris Frontier: The Early History of Tur Abdin. Cambridge University Press.

- Sediyani, İbrahim (2009). Adını arayan coğrafya. Özedönüş Yayınları. ISBN 9786054296002.

- Sinclair, T.A. (1989). Eastern Turkey: An Architectural & Archaeological Survey, Volume III. Pindar Press.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Altıntaş, Midyat. |