Iran–Russia relations

Relations between the Grand Duchy of Moscow and the Persian Empire (Iran), officially commenced in 1521, with the Safavids in power.[1] Past and present contact between Russia and Iran have long been complicatedly multi-faceted; often wavering between collaboration and rivalry. The two nations have a long history of geographic, economic, and socio-political interaction. Mutual relations have often been turbulent, and dormant at other times. Currently Russia and Iran act as economic partners to one another, since both countries are under sanctions by much of the Western world.[2]

_01.jpg)

| |

Iran |

Russia |

|---|---|

Since the fall of the Soviet Union, the two neighboring nations have generally enjoyed very close cordial relations. Iran and Russia are strategic allies[3][4][5] and form an axis in the Caucasus alongside Armenia. Iran and Russia are also military allies in the conflicts in Syria and Iraq and partners in Afghanistan and post-Soviet Central Asia. Due to Western economic sanctions on Iran, Russia has become a key trading partner, especially in regard to the former's excess oil reserves. Militarily, Iran is the only country in Western Asia that has been invited to join the Collective Security Treaty Organization, Russia's own international treaty organization in response to NATO. While much of the Iranian military uses Iranian-manufactured weapons and domestic hardware, Iran still purchases some weapons systems from Russia. In turn, Iran has helped Russia with its drone technology and other military technology. Iran has its embassy in Moscow and consulates in the cities of Astrakhan and Kazan. Russia has its embassy in Tehran, and consulates in Rasht and Isfahan.

History of Iran–Russia relations

Pre-Safavid era

Contacts between Russians and Persians have a long history, extending back more than a millennium.[6] There were known commercial exchanges as early as the 8th century AD between Persia and Russia.[1] They were interrupted by the Mongol invasions in the 13th and 14th centuries but started up again in the 15th century with the rise of the state of Muscovy. In the 9th–11th century AD, there were repetitive military raids undertaken by the Rus' between 864 and 1041 on the Caspian Sea shores of what are nowadays Iran, Azerbaijan, and Dagestan as part of the Caspian expeditions of the Rus'.[7] Initially, the Rus' appeared in Serkland in the 9th century traveling as merchants along the Volga trade route, selling furs, honey, and slaves. The first small-scale raids took place in the late 9th and early 10th century. The Rus' undertook the first large-scale expedition in 913; having arrived on 500 ships, they pillaged the Gorgan region, in the territory of present-day Iran, and the areas of Gilan and Mazandaran, taking slaves and goods.

Safavid Empire–Russian Empire

It was not until the 16th century that formal diplomatic contacts were established between Persia and Russia, with the latter acting as an intermediary in the trade between England and Persia. Transporting goods across Russian territory meant that the English could avoid the zones under Ottoman and Portuguese control.[1] The Muscovy Company (also known as the Russian Company) was founded in 1553 to expand the trade routes across the Caspian sea.[1] Moscow's role as an intermediary in exchanges between Britain and Persia led Russian traders to set up business in urban centres across Persia, as far south as Kashan.[1] The Russian victories over the Kazan Khanate in 1552 and the Astrakhan Khanate in 1556 by Tsar Ivan IV (r. 1533–84) revived trade between Iran and Russia via the Volga-Caspian route and marked the first Russian penetration of the Caucasus and the Caspian area.[6] Though these commercial exchanges in the latter half of the 16th century were limited in scope, they nonetheless indicate that the fledgling entente between the two countries emerged as a result of opposition to the neighboring Ottoman Empire.

Diplomatic relations between Russia and Iran date back to 1521, when the Safavid Shah Ismail I sent an emissary to visit the Czar Vasili III. As the first diplomatic contacts between the two countries was being established, Shah Ismail was also working hard with the aim of joining forces against their mutual enemy, neighboring Ottoman Turkey.[1] On several occasions, Iran offered Russia a deal exchanging a part of its territory (for example Derbent and Baku in 1586) for its support in its wars against their Ottoman archrivals.[1] In 1552–53, Safavid Iran and the Muscovy state in Russia exchanged ambassadors for the first time, and, starting in 1586, they established a regular diplomatic relationship. In 1650, extensive contact between the two people, culminated in the Russo-Persian War (1651–53), after which Russia had to cede its footholds in the North Caucasus to the Safavids. In the 1660s the famous Russian Cossack ataman Stenka Razin raided, and occasionally wintered at, Persia's north coast, creating diplomatic problems for the Russian Czar in his dealings with the Persian Shah.[8] The Russian song telling the tragic semi-legendary story of Razin's relationship with a Persian princess remains popular to this day.

Peace reigned for many decades between the two peoples after these conflicts, in which trade and migration of peoples flourished. The decline of the Safavid and Ottoman state saw the rise of Imperial Russia on the other hand. After the fall of Shah Sultan Husayn brought the Safavid dynasty to an end in 1722, the greatest threats facing Persia were Russian and Ottoman ambitions for territorial expansion in the Caspian region—north-western Persia specifically. During the Safavid period, Russian and Persian power was relatively evenly balanced.[1] Overall, the common anti-Ottoman struggle served as the main common political interest for Iran and Russia throughout the period of Safavid rule, with several attempts to conclude an anti-Ottoman military treaty.[6] Following Shah Husayn's fall, the relationship lost its symmetry, but it was largely restored under Nader Shah.[1]

In his later years of rule, Peter the Great found himself in a strong enough position to increase Russian influence more southwards in the Caucasus, the Caspian Sea and the Black Sea, challenging both the Safavids and the Ottomans. He made the city of Astrakhan his base for his hostilities against Persia, created a shipyard, and attacked the weakened Safavids in the Russo-Persian War (1722–1723), capturing many of its territories in the Caucasus and northern mainland Iran for several years. After several years of political chaos in Persia following the fall of the Safavids, a new and powerful Persian empire was born under the highly successful military leader Nader Shah. Fearing a costly war which would most likely be lost against Nader and also being flanked by the Turks in the west, the Russians were forced to give back all territories and retreat from the entire Caucasus and northern mainland Iran as according to the Treaty of Resht (1732) and Treaty of Ganja (1735) during the reign of Anna of Russia. The terms of the treaty also included the first instance of close Russo-Iranian collaboration against a common enemy, in this case the Ottoman Turks.[9][10]

Qajar Persia–Russian Empire

Irano-Russian relations particularly picked up again following the death of Nader Shah and the dissolution of his Afsharid Dynasty which gave eventually way to the Qajarid dynasty in the mid-18th century. The first Qajar Persian Ambassador to Russia was Mirza Abolhassan Khan Ilchi. After the rule of Agha Mohammad Khan, who stabilized the nation and re-established Iranian suzerainty in the Caucasus,[11] the Qajarid government was quickly absorbed with managing domestic turmoil, while rival colonial powers rapidly sought a stable foothold in the region. While the Portuguese, British, and Dutch competed for the south and southeast of Persia in the Persian Gulf, the Russian Empire largely was left unchallenged in the north as it plunged southward to establish dominance in Persia's northern territories. Plagued with internal politics, the Qajarid government found itself incapable of rising to the challenge of facing its northern threat from Russia.

A weakened and bankrupted royal court, under Fath Ali Shah, was forced to sign the notoriously unfavourable Treaty of Gulistan (1813) following the outcome of the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813), irrevocably ceding what is modern-day Dagestan, Georgia, and large parts of the Republic of Azerbaijan. The Treaty of Turkmenchay (1828) was the outcome of the Russo-Persian War (1826-1828), which resulted in the loss of modern-day Armenia and the remainder of the Azerbaijan Republic, and granted Russia several highly beneficial capitulatory rights, after efforts and initial success by Abbas Mirza failed to ultimately secure Persia's northern front.[12] By these two treaties, Iran lost swaths of its integral territories that had made part of the concept of Iran for centuries.[13] The area to the north of the Aras River, which included the territories of the contemporary nations of Georgia, Azerbaijan, Armenia and the North Caucasian Republic of Dagestan, were Iranian territory until they were occupied by Russia in the course of the 19th century.[14][15][16][17][18][19]

Anti-Russian sentiment was so high in Persia during that time that uprisings in numerous cities were formed. The famous Russian intellectual, ambassador to Persia, and Alexander Pushkin's best friend, Alexander Griboyedov, was killed along with hundreds of Cossacks by angry mobs in Tehran during these uprisings. With the Russian Empire still advancing south in the course of two wars against Persia, and the treaties of Turkmanchay and Golestan in the western frontiers, plus the unexpected death of Abbas Mirza in 1823, and the murder of Persia's Grand Vizier (Mirza AbolQasem Qa'im Maqām), Persia lost its traditional foothold in Central Asia.[20] The Treaty of Akhal, in which the Qajarid's were forced to drop all claims on Central Asia and parts of Turkmenistan, topped off Persian losses to the global emerging power of Imperial Russia.

.jpg)

By the end of the 19th century, the Russian Empire's dominance became so pronounced that Tabriz, Qazvin, and a host of other cities were occupied by Russia, and the central government in Tehran was left with no power to even select its own ministers without the approval of the Anglo-Russian consulates. Morgan Shuster, for example, had to resign under tremendous British and Russian pressure on the royal court. Shuster's book "The Strangling of Persia"[21] is an account of these times, and a harsh criticism of the Russian and British Empires. Northern Iran at this point was officially a sphere of influence of Imperial Russia, and many ethnic Russian settlements were established there.

In the same period, by a proposal of the Shah with the backing of the Tsar, the Russians founded the Persian Cossack Brigade, which and would prove to be crucial in the next few decades of Iranian history and Irano-Russian relations. The Persian Cossacks were organized along Russian lines and controlled by Russian officers.[22] They dominated Tehran and most northern centers of living.

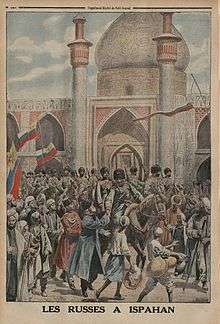

The Russians also organized a banking institution in Iran, which they established in 1890.[23] In 1907, Russia and Britain divided Iran into three segments that served their mutual interests, in the Anglo-Russian Entente of 1907.[22] The Russians gained control over the northern areas of Iran, which included the cities of Tabriz, Tehran, Mashad, and Isfahan. The British were given the southeastern region and control of the Persian Gulf, and the territory between the two regions was classified as neutral territory.

These, and a series of climaxing events such as the Russian shelling of Mashad's Goharshad Mosque in 1911, and the shelling of the Persian National Assembly by the Russian Colonel V. Liakhov, led to a surge in widespread anti-Russian sentiments across the nation.

Pahlavi–Soviet Union

One result of the public outcry against the ubiquitous presence of Imperial Russia in Persia was the Constitutionalist movement of Gilan, which followed up the Persian Constitutional Revolution. Many participants of the revolution were Iranians educated in the Caucasus, direct émigrés (also called Caucasian muhajirs) from the Caucasus, as well as Armenians that at the same period were busy with establishing the Dashnaktsutyun party as well as operations directed against the neighboring Ottoman Empire. The rebellion in Gilan, headed by Mirza Kuchak Khan led to an eventual confrontation between the Iranian rebels and the Russian army, but was disrupted with the October Revolution in 1917.

As a result of the October Revolution, thousands of Russians fled the country, many to Persia. Many of these refugees settled in northern Persia creating their own communities of which many of their descendants still populate the country. Some notable descendants of these Russian refugees in Persia include the political activist and writer Marina Nemat and the former general and deputy chief of the Imperial Iranian Air Force Nader Jahanbani, whose mother was a White émigré.

Russian involvement however continued on with the establishment of the short-lived Persian Socialist Soviet Republic in 1920, supported by Azeri and Caucasian Bolshevik leaders. After the fall of this republic, in late 1921, political and economic relations were renewed. In the 1920s, trade between the Soviet Union and Persia reached again important levels. Baku played a particularly significant role as the venue for a trade fair between the USSR and the Middle East, notably Persia.[24]

In 1921, Britain and the new Bolshevik government entered into an agreement that reversed the division of Iran made in 1907. The Bolsheviks returned all the territory back to Iran, and Iran once more had secured navigation rights on the Caspian Sea. This agreement to evacuate from Iran was made in the Russo-Persian Treaty of Friendship (1921), but the regaining of Iranian territory did not protect the Qajar Dynasty from a sudden coup d'état led by Colonel Reza Shah.[22]

In 1941, as the Second World War raged, the Soviet Union and the United Kingdom launched an undeclared joint invasion of Iran, ignoring its plea of neutrality.

In a revealing cable sent on July 6, 1945 by the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union, the local Soviet commander in northern Azerbaijan was instructed as such:

- "Begin preparatory work to form a national autonomous Azerbaijan district with broad powers within the Iranian state and simultaneously develop separatist movements in the provinces of Gilan, Mazandaran, Gorgan, and Khorasan".[25]

After the end of the war, the Soviets supported two newly formed in Iran, the Azerbaijan People's Government and the Republic of Mahabad, but both collapsed in the Iran crisis of 1946. This postwar confrontation brought the United States fully into Iran's political arena and, with Cold War starting, the US quickly moved to convert Iran into an anti-communist ally.

Post 1979

The Soviet Union was the first state to recognize the Islamic Republic of Iran, in February 1979.[26] During the Iran–Iraq War, however, it supplied Saddam Hussein with large amounts of conventional arms. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Khomeini deemed Islam principally incompatible with the communist ideals (such as atheism) of the Soviet Union, leaving the secular Saddam as an ally of Moscow.

After the war, especially with the fall of the USSR, Tehran–Moscow relations experienced a sudden increase in diplomatic and commercial relations, and Iran soon even began purchasing weapons from Russia. By the mid-1990s, Russia had already agreed to continue work on developing Iran's nuclear program, with plans to finish constructing the nuclear reactor plant at Bushehr, which had been delayed for nearly 20 years.

During the East Prigorodny conflict, and Georgian–Ossetian conflict, Iran secretly supported Ossetian separatism against Georgia, and sided with the Ossetians against Ingush and Chechens in the conflict.

Current relations

As tension between the United States and Iran escalates, the country is finding itself further pushed into an alliance with Russia, as well as China. Iran, like Russia, "views Turkey's regional ambitions and the possible spread of some form of pan-Turkic ideology with suspicion".[27]

Russia and Iran also share a common interest in limiting the political influence of the United States in Central Asia. This common interest has led the Shanghai Cooperation Organization to extend to Iran observer status in 2005, and offer full membership in 2006. Iran's relations with the organization, which is dominated by Russia and China, represents the most extensive diplomatic ties Iran has shared since the 1979 revolution. Iran and Russia have co-founded the Gas Exporting Countries Forum along with Qatar.

Military

Unlike previous years in which Iran's air fleet was entirely Western-made, Iran's Air Force and civilian air fleet are increasingly becoming domestically and Russian built as the US and Europe continue to maintain sanctions on Iran.[28][29][30] In 2010, Iran's refusal to halt uranium enrichment led the UN to pass a new resolution, number 1929 to vote for new sanctions against Iran which bans the sale of all types of heavy weaponry (including missiles) to Iran. This resulted in the cancellation of the delivery of the S-300 system to Iran:[31] In September 2010 Russian President Dmitry Medvedev signed a decree banning the delivery of S-300 missile systems, armored vehicles, warplanes, helicopters and ships to Iran.[32] Mahmoud Ahmadinejad also criticised Russia for kowtowing to the United States.[33] As a result of the cancellation, Iran brought suit against Russia in Swiss court and in response to the lawsuit Russia threatened to withdraw diplomatic support for Iran in the nuclear dispute.[34]

Since the outbreak of the Syrian civil war in 2011, Iran and Russia have become the Syrian government's principal allies in the conflict, openly providing armed support. Meanwhile, Russia's own relations with the West plummeted due the Ukraine crisis, the 2018 Skripal poisoning incident in Great Britain, and alleged Russian interference with Western politics, prompting the U.S. and Europe to retaliate with sanctions against Russia. As a result, Russia has shown a degree willingness to ally with Iran militarily. Following the JCPOA agreement, President Vladimir Putin lifted the ban in 2015 and the deal for the S-300 missile defense system to Iran was revived.[35] The delivery was completed in November 2016 and was to be followed by a $10 billion deal that included helicopters, planes and artillery systems.[36]

Trade

In addition to their trade and cooperation in hydrocarbons, Iran and Russia have also expanded trade ties in many non-energy sectors of the economy, including a large agriculture agreement in January 2009 and a telecommunications contract in December 2008.[37] In July 2010, Iran and Russia signed an agreement to increase their cooperation in developing their energy sectors. Features of the agreement include the establishment of a joint oil exchange, which with a combined production of up to 15 million barrels of oil per day has the potential to become a leading market globally.[38] Gazprom and Lukoil have become increasingly involved in the development of Iranian oil and gas projects.

In 2005, Russia was the seventh largest trading partner of Iran, with 5.33% of all exports to Iran originating from Russia.[39] Trade relations between the two increased from US$1 billion in 2005 to $3.7 billion in 2008.[37] Motor vehicles, fruits, vegetables, glass, textiles, plastics, chemicals, hand-woven carpet, stone and plaster products were among the main Iranian non-oil goods exported to Russia.[40]

Relations between Russia and Iran have increased as both countries are under U.S. sanctions and are seeking new trade partners. The two countries signed a historic US$20 billion oil for goods deal in August 2014.[41][42][43]

Eurasian Economic Union

As Iran and Russia economic and geo-political relations have improved over the years, Russia and the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) have opted for Iran to join the EEU as well. Currently, only one EEU country, Armenia, shares a land border with Iran. Iran currently remains a key partner of the Eurasian Economic Union.

Iran has expressed interest in joining the EEU.[44] During a meeting between Kazakhstan President Nursultan Nazarbayev and Iranian President Hassan Rouhani, they discussed the prospect of cooperation between the customs union and Iran. According to the Iranian Ambassador to Russia, Mehdi Sanaei, Iran is focusing on signing an agreement with the EEU in 2015 regarding mutual trade and reduction of import tariffs to central Asian countries and trading in national currencies as part of the agreement rather than in US dollars.[45]

In May 2015, the Union gave the initial go-ahead to signing a free trade agreement with Iran. Described as the EEU's "key partner in the Middle East" by Andrey Slepnev, the Russian representative on the Eurasian Economic Commission board in an expert-level EEU meeting in Yerevan,[46] Viktor Khristenko furthermore noted that Iran is an important partner for all the EEU member states. He stated that "Cooperation between the EEU and Iran is an important area of our work in strengthening the economic stability of the region".[47]

Polls

According to 2015 data from Pew Research Center, 54% of Russians have a negative opinion of Iran, with 34% expressing a positive opinion.[48] According to a 2013 BBC World Service poll, 86% of Russians view Iran's influence positively, with 10% expressing a negative view.[49] A Gallup poll from the end of 2013 showed Iran ranked as sixth greatest threat to peace in the world according to Russian view (3%), after United States (54%), China (6%), Iraq (5%), and Syria (5%).[50] According to a December 2018 survey by IranPoll, 63.8% of Iranians have a favorable view of Russia, with 34.5% expressing an unfavorable view.[51]

See also

References

- Relations between Tehran and Moscow, 1979–2014. Academia.edu. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- MacFarquhar, Neil. "Putin Lifts Ban on Russian Missile Sales to Iran". The New York Times. Retrieved April 14, 2016.

- Ozbay, Fatih; Aras, Bulent (2008). "The limits of the Russian-Iranian strategic alliance: its history and geopolitics, and the nuclear issue". Korean Journal of Defense Analysis. 20 (1): 47–62. doi:10.1080/10163270802006321. hdl:11729/299. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "The Strategic Partnership of Russia and Iran". Strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "Russia and Iran: Strategic Partners or Competing Regional Hegemons? A Critical Analysis of Russian-Iranian Relations in the Post-Soviet Space". Studentpulse.com. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- "RUSSIA i. Russo-Iranian Relations up to the Bolshevik Revolution". Iranicaonline.org. Retrieved 24 September 2015.

- Logan (1992), p. 201

- O'Rourke, Shane (2000). Warriors and Peasants. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Mikaberidze, Alexander (2011). "Treaty of Ganja (1735)". In Mikaberidze, Alexander (ed.). Conflict and Conquest in the Islamic World: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 329. ISBN 978-1598843361.

- Tucker, Ernest (2006). "Nāder Shah". Encyclopædia Iranica Online. Retrieved 5 January 2014.

- Kazemzadeh 1991, pp. 328–330.

- Cronin, Stephanie (2012). The Making of Modern Iran: State and Society under Riza Shah, 1921–1941. Routledge. p. 90. ISBN 978-1136026942.

- Fisher et al. 1991, p. 329.

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press. pp. 69, 133. ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3.

- L. Batalden, Sandra (1997). The newly independent states of Eurasia: handbook of former Soviet republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-89774-940-4.

- E. Ebel, Robert, Menon, Rajan (2000). Energy and conflict in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-7425-0063-1.

- Andreeva, Elena (2010). Russia and Iran in the great game: travelogues and orientalism (reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-415-78153-4.

- Çiçek, Kemal, Kuran, Ercüment (2000). The Great Ottoman-Turkish Civilisation. University of Michigan. ISBN 978-975-6782-18-7.

- Ernest Meyer, Karl, Blair Brysac, Shareen (2006). Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. Basic Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-465-04576-1.

- Nasser Takmil Homayoun. Kharazm: What do I know about Iran?. 2004. ISBN 964-379-023-1 p.78.

- Morgan Shuster, The Strangling of Persia: Story of the European Diplomacy and Oriental Intrigue That Resulted in the Denationalization of Twelve Million Mohammedans. ISBN 0-934211-06-X

- Ziring, Lawrence (1981). Iran, Turkey, and Afghanistan, A Political Chronology. United States: Praeger Publishers. ISBN 0-03-058651-8.

- Basseer, Clawson & Floor 1988, pp. 698–709.

- Etienne Forestier-Peyrat, "Red Passage to Iran: The Baku Trade Fair and the Unmaking of the Azerbaijani Borderland, 1922–1930", Ab Imperio, Vol 2013, Issue 4, pp. 79–112.

- Decree of the CC CPSU Politburo to Mir Bagirov, CC Secretary of the Communist Party of Azerbaijan, on "measures to Organize a Separatist Movement in Southern Azerbaijan and Other Provinces of Northern Iran". Translation provided by The Cold War International History Project at The Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars.

- Goodarzi, Jubin M. (January 2013). "Syria and Iran: Alliance Cooperation in a Changing Regional Environment" (PDF). Middle East Studies. 4 (2): 31–59. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- Herzig Edmund, Iran and the former Soviet South, Royal Institute for International Affairs, 1995, ISBN 1-899658-04-1, p.9

- "Middle East | Iran air safety hit by sanctions". BBC News. 2005-12-06. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

- "Iran to buy five TU 100-204 planes from Russia". Payvand.com. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-06-14. Retrieved 2006-07-15.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- John Pike. "Analysts Say Iran-Russia Relations Worsening". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Medvedev bans sale of S-300 missiles, other weapons to Iran (Update 1)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2010-11-13. Retrieved 2010-11-03.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Strokan, Sergey. "Russia and Iran: Heading toward a political earthquake?" Archived 2013-02-02 at Archive.today RT, 15 August 2012.

- Putin Lifts Ban On Supplies Of S-300 Missiles To Iran

- Russia Completes S-300 Delivery to Iran

- "Tehran Times". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Iran Investment Monthly Aug 2010.pdf" (PDF). Turquoisepartners.com. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

- "The Cost of Economic Sanctions on Major Exporters to Iran". Payvand.com. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

- http://www.iran-daily.com/1388/3414/html/economy.htm#s383292. Retrieved 2009-06-07. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Trotman, Andrew (2014-08-06). "Vladimir Putin signs historic $20bn oil deal with Iran to bypass Western sanctions". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- "Russia and Iran strike oil agreement". CNBC.com. 2014-08-06. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- Jonathan Saul and Parisa Hafezi (2 April 2014). "Iran, Russia working to seal $20 billion oil-for-goods deal: sources". Reuters. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- "Iran Plans to Sign Agreement With Eurasian Economic Union in 2015". Sputniknews.com. 2015-01-27. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

- "Iran Seeks Trade Agreement with Eurasian Union". Asbarez.com. 2015-02-06. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

- "PressTV-Eurasian union okays free trade with Iran". Presstv.ir. Retrieved 4 June 2015.

- "Tehran Times". Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- Global Indicators Database. Pew Research Center.

- 2013 World Service Poll BBC

- "End of year 2013 : Russia" (PDF). Wingia.com. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2016-10-22.

- "State of Iran Survey Series". IranPoll. February 8, 2019.

Sources

- Basseer, P.; Clawson, P.; Floor, W. (1988). "BANKING". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 7. pp. 698–709.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1991). "Iranian relations with Russia and the Soviet Union, to 1921". In Peter, Avery; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran (Vol. 7). Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521200950.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fisher, William Bayne; Avery, P.; Hambly, G. R. G; Melville, C. (1991). The Cambridge History of Iran. 7. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521200954.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz, Russia and Britain in Persia, A study in Imperialism, 2821, Yale University Press.

- http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/russia-i-relations; RUSSIA i. Russo-Iranian Relations up to the Bolshevik Revolution.

- http://www.iranicaonline.org/articles/russia-iii-iranian-relations-post-soviet; RUSSIA iii. Russo-Iranian Relations in the Post-Soviet Era (1991–present)

- Cronin, Stephanie. Iranian-Russian Encounters: Empires and Revolutions Since 1800. Routledge, 2013. ISBN 978-0415624336.

- Deutschmann, Moritz. Iran and Russian Imperialism: The Ideal Anarchists, 1800-1914. Routledge, 2015. ISBN 978-1138937017.

- Vladislav M Zubok. "Stalin, Soviet Intelligence, and the Struggle for Iran, 1945–53." Diplomatic History, Volume 44, Issue 1, January 2020, Pages 22–46

- Koolaee, Elaheh; Mousavi, Hamed; Abedi, Afifeh (2020). "Fluctuations in Iran-Russia Relations During the Past Four Decades". Iran and the Caucasus. 24 (2): 216–232. doi:10.1163/1573384X-20200206.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Relations of Iran and Russia. |