Derbent

Derbent (Russian: Дербе́нт; Persian: دربند; Lezgian: Кьвевар; Azerbaijani: Dərbənd; Avar: Дербенд), formerly romanized as Derbend,[8] is a city in the Republic of Dagestan, Russia, located on the Caspian Sea. It is the southernmost city in Russia, and it is the second-most important city of Dagestan. Population: 119,200 (2010 Census);[3] 101,031 (2002 Census);[9] 78,371 (1989 Census).[10]

Derbent Дербент | |

|---|---|

City[1] | |

| Other transcription(s) | |

| • Azerbaijani | Dərbənd |

| • Lezgian | Кьвевар, Дербенд |

| • Avar | Дербенд |

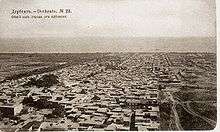

Derbent in 2017 | |

_(2014).png) Coat of arms | |

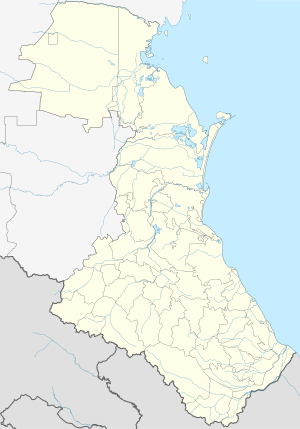

Location of Derbent

| |

Derbent Location of Derbent  Derbent Derbent (Republic of Dagestan) | |

| Coordinates: 42°03′N 48°18′E | |

| Country | Russia |

| Federal subject | Dagestan[1] |

| Founded | 438 |

| City status since | 1840 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Khizri M. Abakarov |

| Area | |

| • Total | 69.63 km2 (26.88 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 0 m (0 ft) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 119,200 |

| • Estimate (2018)[4] | 123,720 (+3.8%) |

| • Rank | 137th in 2010 |

| • Density | 1,700/km2 (4,400/sq mi) |

| • Subordinated to | City of Derbent[1] |

| • Capital of | Republic of Dagestan[1] |

| • Capital of | City of Derbent[1], Derbentsky District[1] |

| • Urban okrug | Derbent Urban Okrug[5] |

| • Capital of | Derbent Urban Okrug[5], Derbentsky Municipal District |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (MSK |

| Postal code(s)[7] | 368600 |

| Dialing code(s) | +7 87240 |

| OKTMO ID | 82710000001 |

| Twin towns | Yakima, Kronstadt, Ganja, Hadera, Pskov |

| Website | www |

Derbent occupies the narrow gateway between the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus Mountains connecting the Eurasian Steppe to the north and the Iranian Plateau to the south.

Derbent claims to be the oldest city in Russia with historical documentation dating to the 8th century BCE.[11] Due to its strategic location, over the course of history, the city changed ownership many times, particularly among the Persian, Arab, Mongol, Timurid, Shirvan and Iranian kingdoms. In the 19th century, the city passed from Iranian into Russian hands by the Treaty of Gulistan of 1813.[12]

Etymology

Derbent is derived from Persian "Darband" (Persian: دربند, lit. 'Barred gate', from dar “gate” + band “bar,” lit., “barred gate”[13]), referring to the adjacent pass. It is often identified with the Gates of Alexander, a legendary barrier supposedly built by Alexander the Great in the Caucasus. The Persian name for the city came into use at the end of the 5th or the beginning of the 6th century AD, when the city was re-established by Kavadh I of the Sassanid dynasty of Persia, but Derbent was probably already in the Sasanian sphere of influence as a result of the victory over the Parthians and the conquest of Caucasian Albania by Shapur I, the second shah of the Sassanid Persians.[14] The geographical treatise Šahrestānīhā ī Ērānšahr written in Middle Persian mentions the old name of the fortress – Wērōy-pahr (The Gruzinian Guard):

"šahrestan [ī] kūmīs [ī] panj-burg až-i dahāg pad šabestān kard. māniš [ī] *pārsīgān ānōh būd. padxwadayīh [ī] yazdgird ī šabuhrān kard andar tāzišn ī čōl wērōy-pahr [ī] an ālag. (The city of Kūmīs of five towers Aži Dahag made it his own harem. The abode of the Parthians was there. In the reign of Yazdgird, the son of Šabuhr made it during the invasion of the Čōl, at the boundary of the Gruzinian Guard.)".[15]

"-Wėrōy-pahr: "The Gruzinian Guard" The old name of the fortress at Darband;..."[16]

In Arabic texts the city was known as "Bāb al-Abwāb" (Arabic: باب الأبواب, lit. 'Gate of Gates')[17], simply as "al-Bāb" (Arabic: الباب, lit. 'The Gate') or as "Bāb al-Hadid" (Arabic: باب الحديد, lit. 'Gate of Iron / Iron Gate').[18] A similar name, also meaning "Iron Gate", was used by Turkic peoples, in the form of "Demirkapi".[19][20]

History

Derbent's location on a narrow, three-kilometer strip of land in the North Caucasus between the Caspian Sea and the Caucasus mountains is strategic in the entire Caucasus region. Historically, this position allowed the rulers of Derbent to control land traffic between the Eurasian Steppe and the Middle East. The only other practicable crossing of the Caucasus ridge was over the Darial Gorge.

Persian rule

A traditionally and historically Iranian city,[21] the first intensive settlement in the Derbent area dates from the 8th century BC; the site was intermittently controlled by the Persian monarchs, starting from the 6th century BC. Until the 4th century AD, it was part of Caucasian Albania which was a satrap of the Achaemenid Persian Empire, and is traditionally identified with Albana, the capital.[14] The modern name is a Persian word (دربند Darband) meaning "gateway", which came into use in the end of the 5th or the beginning of the 6th century AD, when the city was re-established by Kavadh I of the Sassanid dynasty of Persia,[22] however, Derbent was probably already into the Sasanian sphere of influence as a result of the victory over the Parthians and the conquest of Caucasian Albania by Shapur I, the second shah of the Sassanid Persians.[14] In the 5th century Derbent also functioned as a border fortress and the seat of a Sassanid marzban.[14]

The 20-meter-high (66 ft) walls with thirty north-looking towers are believed to belong to the time of Kavadh's son, Khosrau I, who also directed the construction of Derbent's fortress.[23]

The Sassanid fortress does not exist any more, as the famous Derbent fortress as it stands today was built from the 12th century onward.[24] Some say that the level of the Caspian was formerly higher and that the lowering of the water level opened an invasion route that had to be fortified.[25] The chronicler Movses Kaghankatvatsi wrote about "the wondrous walls, for whose construction the Persian kings exhausted our country, recruiting architects and collecting building materials with a view of constructing a great edifice stretching between the Caucasus Mountains and the Great Eastern Sea." Derbent became a strong military outpost and harbour of the Sassanid Empire. During the 5th and 6th centuries, Derbent also became an important center for spreading the Christian faith in the Caucasus.

During periods when the Sasanians were distracted by war with the Byzantines or protracted battles with the Hephthalites in the eastern provinces, the northern tribes succeeded in advancing into the Caucasus. The first Sasanian attempt to seal off the road along the Caspian seacoast at Darband by means of a mud-brick wall has been dated in the reign of Yazdegerd II (438–457 AD).[14]

Movses Kagankatvatsi left a graphic description of the sack of Derbent by the hordes of Tong Yabghu of the Western Turkic Khaganate in 627. His successor, Böri Shad, proved unable to consolidate Tong Yabghu's conquests, and the city was retaken by the Persians, who held it as an integral domain until the Muslim Arab conquest.

As mentioned by the Encyclopedia Iranica, ancient Iranian language elements were absorbed into the everyday speech of the population of Dagestan and Derbent especially during the Sassanian era, and many remain current.[26] In fact, a deliberate policy of “Persianizing” Derbent and the eastern Caucasus in general can be traced over many centuries, from Khosrow I to the Safavid shahs Ismail I, and ʿAbbās the Great.[26] According to the account in the later "Darband-nāma", after construction of the fortifications Khosrow I “moved much folk here from Persia”,[27] relocating about 3,000 families from the interior of Persia in the city of Derbent and neighboring villages.[26] This account seems to be corroborated by the Spanish Arab Ḥamīd Moḥammad Ḡarnāṭī, who reported in 1130 that Derbent was populated by many ethnic groups, including a large Persian-speaking population.[28]

Arab conquest

In 654, Derbent was captured by the Arabs, who called it the Gate of Gates (Bab al-Abwab),[29] following their invasion of Persia. They transformed it into an important administrative center and introduced Islam to the area. The impression of antiquity evoked by these fortifications led many Arab historians to connect them with Khosrow I and to include them among the seven wonders of the world.[14] The Darband fortress was certainly the most prominent Sasanian defensive construction in the Caucasus and could have been erected only by an extremely powerful central government.[14] Because of its strategic position on the northern branch of the Silk Route, the fortress was contested by the Khazars in the course of the Khazar-Arab Wars. The Sassanids had also brought Armenians from Syunik to help protect the pass from invaders; as Arab rule weakened in the region at the end of the ninth century, the Armenians living there were able to establish a kingdom, which lasted until the early years of the thirteenth century.[30][31] The Holy Saviour Armenian Church still rises up in the skyline, though it is used as the Museum of Carpet, Arts and Crafts today due to the decline in the Armenian population. There was also a second Armenian church, and two Armenian schools which served the Armenian community, which numbered about 3,000 in the census of 1913.

Excavations on the eastern side of the Caspian Sea, opposite to Derbent, revealed the Great Wall of Gorgan, the eastern counterpart to the wall and fortifications of Derbent. Similar Sassanian defensive fortifications there—massive forts, garrison towns, long walls—also run from the sea to the mountains.

The Caliph Harun al-Rashid lived in Derbent and brought it into great repute as a seat of the arts and commerce. According to Arab historians, Derbent, with population exceeding 50,000, was the largest city of the 9th century Caucasus. In the 10th century, with the collapse of the Arab Caliphate, Derbent became the capital of an emirate. This emirate often fought losing wars with the neighboring Christian state of Sarir, allowing Sarir to manipulate Derbent's politics on occasion. Despite that, the emirate outlived its rival and continued to flourish at the time of the Mongol invasion in 1239. In the 14th century, Derbent was occupied by Timur's armies.

Shirvanshah era

The Shirvanshahs dynasty existed as independent or a vassal state, from 861 until 1538; longer than any other dynasty in the Islamic world. They were renowned for their cultural achievements and geopolitical pursuits. The rulers of Shirvan, called the Shirvanshahs, had attempted, and on numerous times, succeeded, to conquer Derbend since the 18th Shirvanshah king, Afridun I, was appointed as the governor of the city. Over the centuries the city changed hands often. The 21st Shirvanshah king, Akhsitan I, briefly reconquered the city. However, the city was lost once again to the northern Kipchaks.

After the Timurud invasion, Ibrahim I of Shirvan, the 33rd Shirvanshah, managed to keep the kingdom of Shirvan independent. Ibrahim I revived Shirvan's fortunes, and through his cunning politics managed to continue without paying tribute. Furthermore, Ibrahim also greatly increased the limits of his state. He conquered the city of Derbend in 1437. The Shirvanshahs integrated the city so closely with their political structure that a new branch of the Shirvan dynasty emerged from Derbend, the Derbenid dynasty. The Derbenid dynasty, being a cadet dynasty of Shirvan, inherited the throne of Shirvan in the 15th century.

In the early 16th century the kingdom of Shirvan was conquered by Shah Ismail of the Safavid dynasty. As Shah Ismail incorporated all the Shirvan possessions, he also inherited Derbend.

Russian annexation

Derbent stayed under Iranian rule, while occasionally briefly taken by the Ottoman Turks such as in 1583 after the Battle of Torches and the Treaty of Istanbul, till the course of the 19th century, when the Russians occupied the city and wider Iranian-ruled swaths of Dagestan.[32][33][34][35][36][37][38]

Being briefly taken by the Russians as a result of the Persian expedition of 1722–23 by Peter the Great, the 1735 Treaty of Ganja, formed by Imperial Russia and Safavid Iran (de facto ruled by Nader Shah), forced Russia to return Derbent and its bastion to Iran. In 1747, Derbent became the capital of the Derbent Khanate of the same name.

During the Persian Expedition of 1796, Derbent was stormed by Russian forces under General Valerian Zubov, but the Russians were forced to retreat due to internal political issues,[39] making it fall under Persian rule again. As a consequence of the Russo-Persian War (1804-1813) and the resulting Treaty of Gulistan of 1813, Derbent and wider Dagestan were forcedly and irrevocably ceded by Qajar Iran to the Russian Empire.[40] For background see Russian conquest of the Caucasus#Caspian Coast.)

In the 1886 population counting of the Dagestan Oblast of Russia's Caucasus Viceroyalty, of the 15,265 inhabitants Derbent had, 8,994 (58,9%) were of Iranian descent (Russian: персы) thus comprising an absolute majority in the town.[41]

Geography

The modern city is built near the western shores of the Caspian Sea, south of the Rubas River, on the slopes of the Tabasaran Mountains (part of the Bigger Caucasus range). Derbent is well served by public transport, with its own harbor, a railway going south to Baku, and the Baku to Rostov-on-Don road.

To the north of the town is the monument of the Kirk-lar, or forty heroes, who fell defending Dagestan against the Arabs in 728. To the south lies the seaward extremity of the Caucasian wall (fifty metres long), otherwise known as Alexander's Wall, blocking the narrow pass of the Iron Gate or Caspian Gates (Portae Athanae or Portae Caspiae). When intact, the wall had a height of 9 m (29 ft) and a thickness of about 3 m (10 ft) and, with its iron gates and numerous watch-towers, defended Persia's frontier.[22]

Climate

Derbent has a cold semi-arid climate (Köppen climate classification BSk).

| Climate data for Derbent | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 26.7 (80.1) |

26.6 (79.9) |

28.3 (82.9) |

30.1 (86.2) |

34.2 (93.6) |

35.3 (95.5) |

35.8 (96.4) |

38.8 (101.8) |

33.0 (91.4) |

28.0 (82.4) |

28.0 (82.4) |

27.6 (81.7) |

38.8 (101.8) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 4.8 (40.6) |

4.7 (40.5) |

7.4 (45.3) |

13.6 (56.5) |

20.0 (68.0) |

25.4 (77.7) |

28.4 (83.1) |

28.2 (82.8) |

23.7 (74.7) |

17.5 (63.5) |

11.7 (53.1) |

7.2 (45.0) |

16.1 (61.0) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 2.1 (35.8) |

2.0 (35.6) |

4.5 (40.1) |

10.1 (50.2) |

16.3 (61.3) |

21.7 (71.1) |

24.9 (76.8) |

24.6 (76.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

8.9 (48.0) |

4.5 (40.1) |

12.9 (55.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −0.2 (31.6) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

2.2 (36.0) |

7.1 (44.8) |

12.8 (55.0) |

17.9 (64.2) |

21.2 (70.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.9 (62.4) |

11.4 (52.5) |

6.4 (43.5) |

2.3 (36.1) |

10.0 (50.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −18.9 (−2.0) |

−19.0 (−2.2) |

−9.1 (15.6) |

−3.1 (26.4) |

4.1 (39.4) |

8.5 (47.3) |

12.9 (55.2) |

10.7 (51.3) |

5.1 (41.2) |

−3.4 (25.9) |

−9.7 (14.5) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

−19.0 (−2.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 30.7 (1.21) |

31.6 (1.24) |

23.4 (0.92) |

20.9 (0.82) |

22.9 (0.90) |

18.7 (0.74) |

18.9 (0.74) |

24.8 (0.98) |

47.0 (1.85) |

52.2 (2.06) |

48.5 (1.91) |

39.9 (1.57) |

379.5 (14.94) |

| Average precipitation days | 11.0 | 10.9 | 8.7 | 6.1 | 5.9 | 5.8 | 4.9 | 5.2 | 7.3 | 9.3 | 10.6 | 11.2 | 96.8 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 72 | 73 | 102 | 158 | 227 | 260 | 275 | 248 | 193 | 133 | 86 | 67 | 1,894 |

| Source: climatebase.ru[42] | |||||||||||||

Administrative and municipal status

Within the framework of administrative divisions, Derbent serves as the administrative center of Derbentsky District, even though it is not a part of it.[1] As an administrative division, it is incorporated separately as the City of Derbent—an administrative unit with the status equal to that of the districts.[1] As a municipal division, the City of Derbent is incorporated as Derbent Urban Okrug.[5]

Demographics

The main ethnic groups are (2002 Census):[43][44]

- Lezgins (32.6%)

- Azerbaijanis (31.7%)

- Tabasarans (6.4%)

- Dargins (5.5%)

- Russians (5.0%)

- Aghuls (2.9%)

- Rutuls (0.7%)

Jewish community

Jews began to settle in Derbent in ancient times. During the Khazars' reign, they played an important part in the life of the city.[45] The Jewish traveler Benjamin of Tudela mentions Jews living in Derbent in the 12th century, and Christian traveler Wilhelm of Rubruquis writes about a Jewish community in the 13th century. The first mention of Jews in Derbent in modern times is by a German traveler, Adam Olearius, in the 17th century.

Derbent's Jewry suffered during the wars in the 18th century. Nadir Shah of Persia forced many Jews to adopt Islam. After the Russian conquest, many Jews of rural Dagestan fled to Derbent, which became the spiritual center of the Mountain Jews. The Jewish population numbered 2,200 in 1897 (15% of total population) and 3,500 in 1903. In the middle of the 20th century, Jews constituted about a third of the population of Derbent.[46] In 1989, there were 13,000 Jews in the city, but most emigrated after the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In 2002, there were 2,000 Jews with an active synagogue and community center.[47] The chief rabbi of Derbent, Obadiah Isakov, was badly injured in an assassination attempt on July 25, 2013, sparking concerns of further acts of anti-Semitism targeting the Jewish community.[48] In 2016, the Jewish population was down to 1,345.[49]

Economy and culture

The city is home to machine building, food, textile, fishing and fishery supplies, construction materials and wood industries. It is the center of Russian brandy production. The educational infrastructure includes a university as well as several technical schools. On the cultural front, there is a Lezgin drama theater (named after S. Stalsky). About two kilometers (1.2 miles) from the city is the vacation colony of Chayka (Seagull).

The Soviet novelist Yury Krymov named a fictional motor tanker after the city in his book The Tanker "Derbent".

Citadel of Derbend

Derbent resembles a huge museum and has magnificent mountains and shore nearby, and therefore possesses much touristic potential, further increased by UNESCO's classification of the citadel, ancient city and fortress as a World Heritage Site in 2003; however, instability in the region has halted development.

The current fortification and walls were built by the Persian Sassanian Empire as a defensive structure against hostile nomadic people in the north, and continuously repaired or improved by later Arab, Mongol, Timurid, Shirvan and Iranian kingdoms until the early course of the 19th century, as long as its military function lasted. The fortress was built under direction of the Sassanid emperor Khosrow (Chosroes) I.[23]

A large portion of the walls and several watchtowers still remain in reasonable shape. The walls, reaching to the sea, date from the 6th century, Sassanid dynasty period. The city has a well-preserved citadel (Narin-kala), enclosing an area of 4.5 hectares (11 acres), enclosed by strong walls. Historical attractions include the baths, the cisterns, the old cemeteries, the caravanserai, the 18th-century Khan's mausoleum, as well as several mosques. The oldest mosque is the Juma Mosque, built over a 6th-century Christian basilica; it has a 15th-century madrasa. Other shrines include the 17th-century Kyrhlyar mosque, the Bala mosque and the 18th-century Chertebe mosque.

Notable people

- Shahriyar of Derbent, Sasanian commander

- Bella Nisan, ophthalmologist

- Igor Yusufov, politician

- Israel Tsvaygenbaum, artist

- Mushail Mushailov, artist and teacher

- Sergey Izgiyayev, poet, playwright, and translator of Mountain Jewish descent

- Suleyman Kerimov, businessman, investor, and politician

- Tamara Musakhanova, sculptor and ceramist

- Yagutil Mishiev, writer

- Sevil Novruzova, lawyer

Twin towns – sister cities

Derbent is twinned with:[50]

Gallery

.jpg) The old Armenian Church, now used as a venue and Museum

The old Armenian Church, now used as a venue and Museum Russian Orthodox Church of the Intercession

Russian Orthodox Church of the Intercession Memorial of the grieving mother

Memorial of the grieving mother Walls of the Citadel

Walls of the Citadel School number 15

School number 15_02.jpg) Putin visiting an exhibition dedicated to the 2000th anniversary of Derbent in the State Historical Museum

Putin visiting an exhibition dedicated to the 2000th anniversary of Derbent in the State Historical Museum

References

Notes

- Law #16

- "База данных показателей муниципальных образований". Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (2011). "Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года. Том 1" [2010 All-Russian Population Census, vol. 1]. Всероссийская перепись населения 2010 года [2010 All-Russia Population Census] (in Russian). Federal State Statistics Service.

- http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/doc_2018/bul_dr/mun_obr2018.rar; archive date: 26 July 2018; archive URL: https://web.archive.org/web/20180726010024/http://www.gks.ru/free_doc/doc_2018/bul_dr/mun_obr2018.rar.

- Law #6

- "Об исчислении времени". Официальный интернет-портал правовой информации (in Russian). June 3, 2011. Retrieved January 19, 2019.

- Почта России. Информационно-вычислительный центр ОАСУ РПО. (Russian Post). Поиск объектов почтовой связи (Postal Objects Search) (in Russian)

-

- Russian Federal State Statistics Service (May 21, 2004). "Численность населения России, субъектов Российской Федерации в составе федеральных округов, районов, городских поселений, сельских населённых пунктов – районных центров и сельских населённых пунктов с населением 3 тысячи и более человек" [Population of Russia, Its Federal Districts, Federal Subjects, Districts, Urban Localities, Rural Localities—Administrative Centers, and Rural Localities with Population of Over 3,000] (XLS). Всероссийская перепись населения 2002 года [All-Russia Population Census of 2002] (in Russian).

- "Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 г. Численность наличного населения союзных и автономных республик, автономных областей и округов, краёв, областей, районов, городских поселений и сёл-райцентров" [All Union Population Census of 1989: Present Population of Union and Autonomous Republics, Autonomous Oblasts and Okrugs, Krais, Oblasts, Districts, Urban Settlements, and Villages Serving as District Administrative Centers]. Всесоюзная перепись населения 1989 года [All-Union Population Census of 1989] (in Russian). Институт демографии Национального исследовательского университета: Высшая школа экономики [Institute of Demography at the National Research University: Higher School of Economics]. 1989 – via Demoscope Weekly.

- Derbent - Russia’s oldest city: 5,000 and counting Archived May 15, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- Timothy C. Dowling Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond p 728 ABC-CLIO, 2 dec. 2014 ISBN 1598849484

- Zonn, Igor S; Kosarev, Aleksey N; Glantz, Michael; Kostianoy, Andrey G. (2010). The Caspian Sea Encyclopedia. Springer. p. 160.

- "DARBAND (1)". Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- Daryaee, Touraj (2002). Šahrestānīhā Ī Ērānšahr: A Middle Persian Text on Late Antique Geography, Epic, and History. Costa Mesa, California 92628 U.S.A.: Mazda Publishers, Inc. pp. 14, 18. ISBN 1-56859-143-8.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Daryaee., Touraj (2002). Šahrestānīhā Ī Ērānšahr: A Middle Persian Text on Late Antique Geography, Epic, and History. Costa Mesa, California 92628 U.S.A.: Mazda Publishers, Inc. p. 40. ISBN 1-56859-143-8.CS1 maint: location (link)

- McFarquhar, Neil (February 17, 2016). "Derbent as Russia's Oldest City? Think Again, Moscow Says". The New York Times. Retrieved February 17, 2016.

- Chenciner, Robert (October 12, 2012). Daghestan: Tradition and Survival. Routledge. ISBN 9781136107146.

- Pereira, Michael (January 1, 1973). Across the Caucasus. Bles.

- The Modern Part of an Universal History: From the Earliest Account of Time. Compiled from Original Writers. By the Authors of The Antient Part. S. Richardson, T. Osborne, C. Hitch, A. Millar, John Rivington, S. Crowder, P. Davey and B. Law, T. Longman, and C. Ware. 1759.

- Michael Khodarkovsky. "Bitter Choices: Loyalty and Betrayal in the Russian Conquest of the North Caucasus" Cornell University Press, 12 mrt. 2015. ISBN 0801462908 pp 47–52

-

- Kevin Alan Brook. "The Jews of Khazatia" Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 27 sep. 2006. ISBN 978-1442203020 p 126

- Nicolle, David (September 22, 2009). Saracen Strongholds 1100-1500: The Central and Eastern Islamic Lands. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 9781846033759.

- Robert H. Hewsen, Armenia: A historical Atlas, 2001, page 89

- "DAGESTAN". Retrieved June 11, 2015.

- Saidov and Shikhsaidov, pp. 26-27

- Bol’shakov and Mongaĭt, p. 26

- Hoyland, Robert G. (2014). In Gods Path: The Arab Conquests and the Creation of an Islamic Empire. Oxford University Press. p. 113.

- See (in Armenian) Sedrak Barkhudaryan, “Դերբենդի հայ-աղվանական թագավորությունը” (“The Armenian-Caucasian Albanian Kingdom of Derbend”). Patma-Banasirakan Handes . № 3, 1969, pp. 125-147.

- (in Armenian) Matthew of Edessa. Ժամանակնագրություն (Chronicle). Translated by Hrach Bartikyan. Yerevan: Hayastan Publishing, 1973, pp. 151-152, 332, note 132a.

- Swietochowski, Tadeusz (1995). Russia and Azerbaijan: A Borderland in Transition. Columbia University Press. pp. 69, 133. ISBN 978-0-231-07068-3.

- L. Batalden, Sandra (1997). The newly independent states of Eurasia: handbook of former Soviet republics. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 98. ISBN 978-0-89774-940-4.

- E. Ebel, Robert, Menon, Rajan (2000). Energy and conflict in Central Asia and the Caucasus. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-7425-0063-1.

- Andreeva, Elena (2010). Russia and Iran in the great game: travelogues and orientalism (reprint ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-415-78153-4.

- Çiçek, Kemal, Kuran, Ercüment (2000). The Great Ottoman-Turkish Civilisation. University of Michigan. ISBN 978-975-6782-18-7.

- Ernest Meyer, Karl, Blair Brysac, Shareen (2006). Tournament of Shadows: The Great Game and the Race for Empire in Central Asia. Basic Books. p. 66. ISBN 978-0-465-04576-1.

- "Citadel, Ancient City and Fortress Buildings of Derbent". Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- "Alexey Yermolov's Memoirs". Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- "Russia at War: From the Mongol Conquest to Afghanistan, Chechnya, and Beyond ..." Retrieved December 29, 2014.

- НАСЕЛЕНИЕ ДАГЕСТАНА ДАГЕСТАНСКАЯ ОБЛАСТЬ (1886 г.) Retrieved 29 October 2015

- "Climatebase". Retrieved November 4, 2017.

- Правительство РД — Дербент — Муниципальные районы и городские округа Archived January 11, 2012, at the Wayback Machine

- "население дагестана". Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- "DERBENT - JewishEncyclopedia.com". Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- "Saving Another Dying Jewish Language Before It's Too Late". Haaretz. April 19, 2010.

- "Derbent - Jewish Virtual Library". Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- "После покушения на раввина евреи Дагестана живут в страхе". Retrieved June 9, 2015.

- Derbent as Russia's Oldest City? Think Again, Moscow Says

- "Города-побратимы". derbent.ru (in Russian). Derbent. Retrieved February 3, 2020.

Sources

- Народное Собрание Республики Дагестан. Закон №16 от 10 апреля 2002 г. «Об административно-территориальном устройстве Республики Дагестан», в ред. Закона №106 от 30 декабря 2013 г. «О внесении изменений в некоторые законодательные акты Республики Дагестан». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Дагестанская правда", №81, 12 апреля 2002 г. (People's Assembly of the Republic of Dagestan. Law #16 of April 10, 2002 On the Administrative-Territorial Structure of the Republic of Dagestan, as amended by the Law #106 of December 30, 2013 On Amending Various Legislative Acts of the Republic of Dagestan. Effective as of the day of the official publication.).

- Народное Собрание Республики Дагестан. Закон №6 от 13 января 2005 г. «О статусе и границах муниципальных образований Республики Дагестан», в ред. Закона №43 от 30 апреля 2015 г. «О статусе городского округа с внутригородским делением "Город Махачкала", статусе и границах внутригородских районов в составе городского округа с внутригородским делением "Город Махачкала" и о внесении изменений в отдельные законодательные акты Республики Дагестан». Вступил в силу со дня официального опубликования. Опубликован: "Дагестанская правда", №8, 15 февраля 2005 г. (People's Assembly of the Republic of Dagestan. Law #6 of January 13, 2005 On the Status and Borders of the Municipal Formations of the Republic of Dagestan, as amended by the Law #43 of April 30, 2015 On the Status of the "City of Makhachkala" Urban Okrug with Intra-Urban Divisions, the Status and the Borders of the Intra-City Districts Comprising the "City of Makhachkala" Urban Okrug with Intra-Urban Divisions, and on Amending Various Legislative Acts of the Republic of Dagestan. Effective as of the day of the official publication.).

- Some text used with permission from www.travel-images.com. The original text can be found here .

- M. S. Saidov, ed., Katalog arabskikh rukopiseĭ Instituta IYaL Dagestanskogo filiala AN SSSR (Catalogue of Arabic manuscripts in the H.L.L. Institute of the Dāḡestān branch of the A.N. of the U.S.S.R.) I, Moscow, 1977.

- Idem and A. R. Shikhsaidov, “Derbend-name (k istorii izucheniya)” (Darband-nāma. On the history of research),” in Vostochnye istochniki po istorii Dagestana (Eastern sources on the history of Dāḡestān), Makhachkala, 1980, pp. 564.