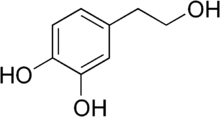

Hydroxytyrosol

Hydroxytyrosol is a phenylethanoid, a type of phenolic phytochemical with antioxidant properties in vitro. In nature, hydroxytyrosol is found in olive leaf and olive oil, in the form of its elenolic acid ester oleuropein and, especially after degradation, in its plain form.[1]

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

4-(2-Hydroxyethyl)-1,2-benzenediol | |

| Other names

3-Hydroxytyrosol 3,4-dihydroxyphenylethanol (DOPET) Dihydroxyphenylethanol 2-(3,4-Di-hydroxyphenyl)-ethanol (DHPE) 3,4-dihydroxyphenolethanol (3,4-DHPEA)[1] | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.114.418 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C8H10O3 | |

| Molar mass | 154.165 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Clear, faint yellow to yellow liquid |

| Boiling point | 174 °C (345 °F; 447 K) |

| 5 g/100 ml | |

| Hazards | |

| Main hazards | Causes skin irritation.

Causes serious eye irritation. May cause respiratory irritation. |

| Safety data sheet | |

| R-phrases (outdated) | R36/37/38 |

| S-phrases (outdated) | S26, S37/39 |

| Related compounds | |

Related alcohols |

benzyl alcohol, tyrosol |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Hydroxytyrosol itself in pure form is a colorless, odorless liquid. The olives, leaves and olive pulp contain large amounts of hydroxytyrosol (compared to olive oil), most of which can be recovered to produce hydroxytyrosol extracts.[1] However, it was found that black olives, such as common canned variety, containing iron(II) gluconate contained little hydroxytyrosol, as iron salts are catalysts for its oxidation.[2]

Hydroxytyrosol is mentioned by the scientific committee of the European Food Safety Authority as one of several olive oil polyphenols under preliminary research for the potential to affect blood lipid levels, although there is no evidence from high-quality clinical research to indicate that this effect exists.[3]

Animal research

As of 2015, the NOAEL for hydroxytyrosol in rats is 250 mg/kg/day, with a LOAEL of 500 mg/kg/day.[4]

See also

- Echinacoside, a hydroxytyrosol-containing glycoside

- Tyrosol

- Verbascoside, another hydroxytyrosol-containing glycoside

References

- M. Baldioli; M. Servili; G. Perretti; G. F. Montedoro (1996). "Antioxidant activity of tocopherols and phenolic compounds of virgin olive oil". Journal of the American Oil Chemists' Society. 73 (11): 1589–1593. doi:10.1007/BF02523530.

- Vincenzo Marsilio; Cristina Campestre; Barbara Lanza (July 2001). "Phenolic compounds change during California-style ripe olive processing". Food Chemistry. 74 (1): 55–60. doi:10.1016/S0308-8146(00)00338-1.

- Sadler MJ (2014). Foods, Nutrients and Food Ingredients with Authorised EU Health Claims; Volume 1 of Woodhead Publishing Series in Food Science, Technology and Nutrition; Section 10.3: Authorised health claim. Elsevier. pp. 214–5. ISBN 9780857098481.

- Heilman J, Anyangwe N, Tran N, Edwards J, Beilstein P, López J (2015). "Toxicological evaluation of an olive extract, H35: Subchronic toxicity in the rat" (PDF). Food and Chemical Toxicology. 84: 18–28. doi:10.1016/j.fct.2015.07.007. PMID 26184542. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

The lowest observed adverse effect level (LOAEL) was the 500 mg HT/kg bw/day based on statistically significant reductions in body weight gain and decreased body weight in males. The no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) was 250 mg HT/kg bw/day, equivalent to 691 mg/kg bw/day of H35 extract.