Holyrood Park

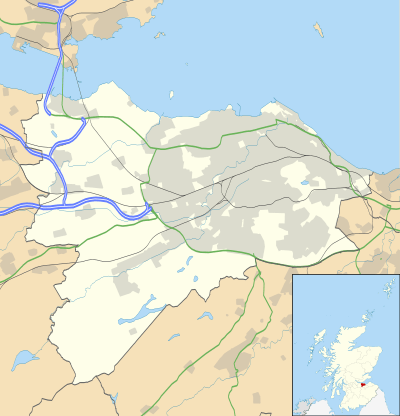

Holyrood Park (also called the Queen's Park or King's Park depending on the reigning monarch's gender) is a royal park in central Edinburgh, Scotland about 1 mile (1.6 kilometres) to the east of Edinburgh Castle. It is open to the public. It has an array of hills, lochs, glens, ridges, basalt cliffs, and patches of gorse, providing a wild piece of highland landscape within its 650-acre (260 ha) area. The park is associated with the royal palace of Holyroodhouse and was formerly a 12th-century royal hunting estate. The park was created in 1541 when James V had the ground "circulit about Arthurs Sett, Salisborie and Duddingston craggis" enclosed by a stone wall.[1]

| Holyrood Park | |

|---|---|

Arthur's Seat is located within Holyrood Park | |

| |

| Type | Urban park |

| Location | Edinburgh |

| Coordinates | 55°56′54″N 3°09′32″W |

| Area | 650 acres (260 ha) |

| Created | 1541 |

| Status | Open all year |

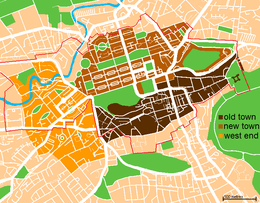

Arthur's Seat, an extinct volcano and the highest point in Edinburgh, is at the centre of the park, with the cliffs of Salisbury Crags to the west. There are three lochs; St Margaret's Loch, Dunsapie Loch, and Duddingston Loch. The ruined St Anthony's Chapel stands above St Margaret's Loch. Queen's Drive is the main route through the Park, and is partly closed on Sundays to motor vehicles.[2] St Margaret's Well and St Anthony's Well are both natural springs within the park. Holyrood Park is located to the south-east of the Old Town, at the edge of the city centre. Abbeyhill is to the north, and Duddingston village to the east. The University of Edinburgh's Pollock Halls of Residence are to the south-west, and Dumbiedykes is to the west.

Holyrood Park is one of Scotland's Properties in Care, owned by Scottish Ministers and managed on their behalf by Historic Environment Scotland.

Natural features

Arthur's Seat

Arthur's Seat is the main peak of the group of hills which form most of Holyrood Park. The hill rises above the city to a height of 251 metres (823 ft), provides excellent views, is quite easy to climb, and is a popular walk. Though it can be climbed from almost any direction, the easiest and simplest ascent is from the East, where a grassy slope rises above Dunsapie Loch, a small artificial loch located between Dunsapie Hill and Arthur's Seat. The loch is fed with water from Alnwickhill in the south of the city, and is a popular location within the park, supporting several bird species.

Salisbury Crags

Salisbury Crags are a series of 46-metre (151 ft) cliffs at the top of a subsidiary spur of Arthur's Seat which rise on the west of Holyrood Park. Below the foot of the cliffs is a large and steep talus slope falling to the floor of Holyrood Park with a track known as the Radical Road running in the space between the two. This track was given its name after it was paved in the aftermath of the Radical War of 1820, using the labour of unemployed weavers from the west of Scotland at the suggestion of Walter Scott.[3]

On the basis of it simply being the same name, Hugo Arnot derived the name from the first Earl of Salisbury who accompanied Edward III of England on one of his invasions of Scotland.[4] James Grant's view of this is that it was "an idle story" and quoted Lord Hailes' derivation from Anglo-Saxon meaning "waste or dry habitation".[5] The modern Gaelic name of the cliffs is Creagan Salisbury, a direct translation of the English; however in 1128, the cliffs were described in a charter under an older Gaelic name, Creag nam Marbh (the Crag of the Dead).[6][7]

The cliffs are formed from steep dolerite and columnar basalt and have a long history of rock climbing on their faces starting from the earliest days of the sport. Harold Raeburn was brought up nearby, and became the leading climber of the Scottish Mountaineering Club not long after he joined it in 1896.[8] By 1900 a number of traditional climbing and sport climbing routes had been recorded by Raeburn and W. Inglis Clark.[9] In recent years the park rangers (previously under the auspices of the Royal Estate and now Historic Scotland, who had taken over management of the park) attempted to regulate access to the cliffs due to hazards to park visitors from loose and falling rocks. Climbers are now restricted to a designated area of the South Quarry, and need to apply for a permit, free of charge, at the education centre in the north of the park in order to be allowed to climb.[10] There is still some activity, though most of it is bouldering rather than free climbing. The finest areas are in the two quarries, although it is only in the South Quarry that climbing is still permitted at this time. The south quarry contains the Black Wall, a well-known bouldering testpiece in the Edinburgh climbing scene. The best known route to climb the Crags is at "Cat Nick" or "Cat's Nick"[11][12][13] which is a cleft in the rocks near the highest point of the Crags. This is named on maps, sometimes leading people to believe that the highest point of the crag is itself so named.

Samson's Ribs

Samson's Ribs are a formation of columnar basalt.

St Margaret's Loch

St Margaret's Loch is a shallow man-made loch to the south of Queen's Drive. It is around 500 m east of Holyrood Palace, and about 100 m north of the ruin of St Anthony's Chapel. Once a boggy marshland, the loch was formed in 1856 as part of Prince Albert's improvement plans for the area surrounding the palace. The loch has been used as a boating pond but is now home to a strong population of ducks, geese, and swans.

Other geographical features

Other geographical features include the Haggis Knowe, Whinny Hill and Hunter's Bog, which drains into St Margaret's Loch.

Cultural heritage

There are traces of prehistoric hill forts within the park, notably on the rocky knoll above Dunsapie Loch. The remains of cultivation terraces can be seen on the eastern slopes of Arthur's Seat.

Holyrood Abbey

The ruined Augustinian Abbey of Holyrood was established in 1128, at the order of King David I of Scotland, within his royal deer-hunting park. The Abbey was in use until the 16th century. It was briefly used as a Chapel Royal by James VII, but was finally ruined in the mid-18th century.

Holyrood Palace

The Royal Palace of Holyroodhouse began as a lodging within the Abbey, but eventually grew into a substantial palace. James IV had the first buildings constructed around 1500, although the bulk of the present building dates from the late 17th century, when it was remodelled in the neo-classical style by Sir William Bruce. It remains as the official residence of the British monarch in Scotland.

St Anthony's Chapel

The origin and the history of the chapel are obscure, but it was certainly built no later than the early 15th century, as in 1426 it is recorded that the Pope gave money for its repair. The chapel may have been linked to the Preceptory of St. Anthony, a skin hospice, which was based in Leith around this time. It may have been linked to the nearby Holyrood Abbey.

It was originally rectangular in shape, around 43 by 18 feet (13.1 by 5.5 m), with 3-foot-thick (0.9 m) walls, and was built with local stone. The tower would have stood just over 39 ft (11.9 m) high, and probably had a spiral stair inside. The chapel is now a ruin: only the north wall and a fragment of west wall remain next to part of an ancillary building.[14]

History

Though the chapel is now in ruinous condition, we do have some idea of what the chapel may once have looked like from historical and archaeological research. 18th century records describe it as being:

"a beautiful Gothick building, well suited to the rugged sublimity of the rock ... and its west end there was a tower .. about forty feet [12 m] high." - Hugot Arnot, The History of Edinburgh 1779

Muschat's Cairn

This cairn is situated by the Duke's Walk at the eastern (Meadowbank) end of Holyrood Park. It commemorates an event on 17 October 1720 when Nichol Muschat, a surgeon, dragged his wife to a nearby spot and brutally murdered her. He was eventually tried and hanged for this crime. At his trial he said that he had simply tired of her.

The present cairn consists of boulders cemented together[15] and was erected in 1823 replacing an earlier cairn which had been removed c.1789. This earlier cairn was formed over several years by the tradition of laying stones on the cairn "in token of the people's abhorrence and reprobation of the deed". It was situated some way to the west of the present cairn with Sir Walter Scott placing it about a furlong to the east of St. Anthony's Chapel.[16] Scott mentions the cairn several times in the novel, The Heart of Midlothian, by siting Jeanie Dean's tryst with the outlaw, George Robertson, at this spot. The site of the so-called Jeanie Deans Cottage can also be seen in Holyrood Park at the south end of St. Leonards Bank.

Road Network

Up until 1844, no definite road existed around the Park. The road network in the park today is a product of Prince Albert's reforms in 1844, which added the circular Victoria Road, later called The Queen's Drive.[17]

The roads in Holyrood Park are private and do not form part of the City of Edinburgh road network. Holyrood Park, including the road network, is under the ownership and care of the Scottish Ministers and managed through Historic Environment Scotland as a Property in Care.[18] Historic Environment Scotland receive no direct funding for the upkeep of the Park roads.[19]

Road Closures

HES has the authority to implement motor vehicle closures to most roads when required or requested. HES may open or close roads at any time in the interest of safety, maintenance or to facilitate organised events.[20]

All roads in the park (except the High Road and access to car parks) are closed to vehicles every Sunday.[21] The road network is also closed for many events and holidays during the year: Christmas, Boxing Day, New Years Day, Edinburgh Marathon, marches etc.the High Road is closed for annual toad migration[22] and during winter evenings after 3:30pm.[23]

To facilitate the road closures, there are gates at the five motor vehicle entrances: Dukes Walk (north east), Holyrood Gait (north west), Horse Wynd (north west), Holyrood Park Road (south west) and Old Church Lane (south east).

During the Spring 2020 coronavirus lockdown, the High Road was closed to motor vehicles at all times. This was at first due to the annual toad migration in March and early April, but Historic Environment Scotland continued the road closure after the toad migration ended.[24]

In June 2020, Historic Environment Scotland announced all roads in Holyrood Park would be closed to motor vehicles on both Saturday and Sunday, 8:30am to 6pm.[25]

Regulations

As a Royal Park, Holyrood Park is protected under the framework of The Parks Regulations Acts, 1872 to 1974, The Holyrood Park Regulations 1971 and subsequent amendments.

The Holyrood Park Regulations 1971[26] prohibit:

- soliciting passengers with a hackney carriage;

- driving or using any vehicle designed to seat more than seven passengers (in addition to the driver), or constructed or adapted for the purpose of any trade or business or as a dwelling, effectively prohibiting commercial vehicles.

The Holyrood Park Amendment Regulations 2005 instituted parking charges at Broad Pavement car park.[27]

Coaches require the written permission of the Scottish Ministers to use Holyrood Park. Coach drivers must obtain a permit which is valid for 12 calendar months. Coach Permits are only valid while coaches are carrying passengers. Empty coaches travelling through the Park are classed as commercial vehicles and liable to a fixed penalty notice. Permits only allow coaches access to The Queen's Drive and High Road and do not allow access to the Low Road between Holyrood Park Road (Commonwealth Pool) and Old Church Lane (Duddingston Village).[28]

Traffic Reduction

In 2011, Historic Scotland started a campaign to reduce traffic passing through Holyrood Park. Martin Gray, Historic Scotland's Royal Parks Visitor Services Manager noted increasing motor traffic in the Park: 'Holyrood Park is a unique green space in the heart of the city. The Park's location makes it very accessible and popular to visitors, but developments around the park have resulted in increasing levels of through-traffic, commercial vehicle misuse and speeding. Large and heavy vehicles cause accelerated wearing of roads surfaces and damage kerbs and traffic islands. They also pose a risk to park users and wildlife who enjoy the use of the Park.'[29]

Cycling Infrastructure

There is a cycle path on the south side of Queen's Drive from St Margaret's Loch to Broad Pavement car park, where it becomes shared use (shared between pedestrians and cyclists) between Broad Pavement car park to the roundabout by the Royal Commonwealth Pool entrance to Holyrood Park.

See also

- Holyrood (disambiguation)

References

- "Edinburgh, Holyrood Park, General and Perimeter Wall". Retrieved 15 September 2010.

- "Try Your Christmas Bike in the Park". CyclingEdinburgh.info. Archived from the original on 8 July 2012. Retrieved 21 December 2007.

- "Salisbury Crags". Retrieved 5 July 2011.

- Arnot, Hugo (1816). The History of Edinburgh,... Thomas Turnbull. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

salisbury.

- Grant, James. Old and New Edinburgh. Retrieved 13 October 2010.

- "Salisbury Crags". Àineaman-Àite na h-Alba. Retrieved 26 January 2018.

- Dùn Èideann nan Gàidheal/Gaelic in Edinburgh. Edinburgh: University of Edinburgh. 2018. p. 4.

- "SMC Pioneers: Harold Andrew Raeburn (1865 – 1926)". Scottish Mountaineering Club. 2007. Archived from the original on 18 June 2015. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- Some climbs on the Salisbury Crags by W. Inglis Clark, Scottish Mountaineering Journal, Volume 3, Number 3, September 1900 (available online).

- "Official guide: Climbing in Holyrood Park" (PDF). Historic Scotland. Retrieved 2 February 2014.

- UKClimbing.com 'logbook' (available online).

- The Cat Nick in Winter, W. Inglis Clark, Scottish Mountaineering Journal, Volume 4, Number 5, May 1897 (available online).

- Bob Henderson's recollections on www.edinphoto.org.uk (available online).

- "Edinburgh, Holyrood Park, Queen's Drive, St Anthony's Chapel and Hermitage". Royal Commission on Ancient and Historic Monuments Scotland. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- "Edinburgh, Holyrood Park, Muschet's Cairn". Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- Scott, Walter. The Waverly anecdotes: illustrative of the incidents, characters ..., Volume 2. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- Wright, Gordon; Adams, Ian; Scott, Michael (1987). A Guide to Holyrood Park and Arthur's Seat. p. 30.

- "Questions and Answers regarding traffic regulations at Holyrood Park" (PDF).

- "Questions and Answers regarding traffic regulations at Holyrood Park" (PDF).

- Historic Environment Scotland (2019). "Guidance Notes: Holding an event in Holyrood Park".

- "Holyrood Park: Park Roads". www.historicenvironment.scot. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "Saving toads with our Holyrood rangers". Historic Environment Scotland Blog. 7 April 2016. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "Holyrood Park: Park Roads". www.historicenvironment.scot. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "Using Holyrood Park and Linlithgow Peel during the pandemic". www.historicenvironment.scot. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- Smith, Joe (10 June 2020). "Holyrood Park road will close to all vehicles at certain times under new rules". edinburghlive. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "The Holyrood Park Regulations 1971" (PDF). Historic Environment Scotland. 1971.

- "The Holyrood Park Amendment Regulations 2005". www.legislation.gov.uk. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "Historic Scotland Starts Traffic Reduction Campaign in Holyrood Park | Edinburgh Guide". www.edinburghguide.com. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

- "Historic Scotland Starts Traffic Reduction Campaign in Holyrood Park | Edinburgh Guide". www.edinburghguide.com. Retrieved 19 June 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Holyrood Park. |