H. L. Hunley (submarine)

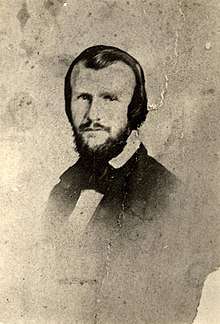

H. L. Hunley, often referred to as Hunley, was a submarine of the Confederate States of America that played a small part in the American Civil War. Hunley demonstrated the advantages and the dangers of undersea warfare. She was the first combat submarine to sink a warship (USS Housatonic), although Hunley was not completely submerged and, following her successful attack, was lost along with her crew before she could return to base. The Confederacy lost 21 crewmen in three sinkings of Hunley during her short career. She was named for her inventor, Horace Lawson Hunley, shortly after she was taken into government service under the control of the Confederate States Army at Charleston, South Carolina.

1864 painting of H. L. Hunley by Conrad Wise Chapman | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | H. L. Hunley |

| Namesake: | Horace Lawson Hunley |

| Builder: | James McClintock |

| Laid down: | Early 1863 |

| Launched: | July 1863 |

| Acquired: | August 1863 |

| In service: | 17 February 1864 |

| Out of service: | 17 February 1864 |

| Status: | Awaiting conservation |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 7.5 short tons (6.8 t) |

| Length: | 39.5 ft (12.0 m) (unconfirmed) |

| Beam: | 3.83 ft (1.17 m) |

| Propulsion: | Hand-cranked ducted propeller |

| Speed: | 4 kn (7.4 km/h; 4.6 mph) (surface) |

| Complement: | 2 officer, 6 enlisted |

| Armament: | 1 spar torpedo |

H. L. HUNLEY (submarine) | |

| |

| Nearest city | North Charleston, South Carolina |

| Coordinates | 32°44′0″N 79°46′0″W |

| Built | 1864 |

| Architect | Park & Lyons; Hunley, McClintock & Watson |

| NRHP reference No. | 78003412[1] |

| Added to NRHP | December 29, 1978 |

Hunley, nearly 40 ft (12 m) long, was built at Mobile, Alabama, and launched in July 1863. She was then shipped by rail on 12 August 1863, to Charleston. Hunley (then referred to as the "fish boat", the "fish torpedo boat", or the "porpoise") sank on 29 August 1863, during a test run, killing five members of her crew. She sank again on 15 October 1863, killing all eight of her second crew, including Horace Hunley himself, who was aboard at the time, even though he was not a member of the Confederate military. Both times Hunley was raised and returned to service.

On 17 February 1864, Hunley attacked and sank the 1,240-displacement ton United States Navy[2] screw sloop-of-war Housatonic, which had been on Union blockade-duty in Charleston's outer harbor. Hunley did not survive the attack and also sank, taking with her all eight members of her third crew, and was lost.

Finally located in 1995, Hunley was raised in 2000, and is on display in North Charleston, South Carolina, at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center on the Cooper River. Examination in 2012, of recovered Hunley artifacts suggests that the submarine was as close as 20 ft (6.1 m) to her target, Housatonic, when her deployed torpedo exploded, which caused the submarine's own loss.[3]

Predecessors

Horace Lawson Hunley provided financing for James McClintock to design three submarines: Pioneer in New Orleans, Louisiana, American Diver built in Mobile, and Hunley.[4]

While the United States Navy was constructing its first submarine USS Alligator, in late 1861, the Confederacy were doing so as well. Hunley, McClintock, and Baxter Watson first built Pioneer, which was tested in February 1862, in the Mississippi River, and was later towed to Lake Pontchartrain, for additional trials. But the Union advance towards New Orleans caused the men to abandon development and scuttle Pioneer the following month.[4] The Bayou St. John Confederate submarine may have been constructed about this time.[5] Hunley and McClintock moved to Mobile, to begin development of a second submarine, American Diver with the collaboration of two others.[4][5] Their efforts were supported by the Confederate States Army. Lieutenant William Alexander of the 21st Alabama Infantry Regiment was assigned to oversee the project. The builders experimented with electric and steam propulsion for the new submarine, before falling back on a simple hand-cranked propulsion system. American Diver was ready for harbor trials by January 1863, but she proved too slow to be practical. Nonetheless, it was decided to tow the submarine down the bay to Fort Morgan and attempt an attack on the Union blockade. However, the submarine foundered in the heavy chop caused by foul weather and the currents at the mouth of Mobile Bay and sank.[6] The crew escaped, but the boat was not recovered.

Construction and testing

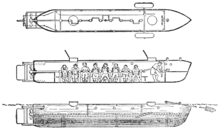

Construction of Hunley began soon after the loss of American Diver. At this stage, Hunley was variously referred to as the "fish boat", the "fish torpedo boat", or the "porpoise". Legend held that Hunley was made from a cast-off steam boiler — perhaps because a cutaway drawing by William Alexander, who had seen her, showed a short and stubby machine. In fact, Hunley was designed and built for her role, and the sleek, modern-looking craft shown in R.G. Skerrett's 1902 drawing is an accurate representation. Hunley was designed for a crew of eight, seven to turn the hand-cranked ducted propeller, ~3.5 Horsepower, and one to steer and direct the boat. Each end was equipped with ballast tanks that could be flooded by valves or pumped dry by hand pumps. Extra ballast was added through the use of iron weights bolted to the underside of the hull. In the event the submarine needed additional buoyancy to rise in an emergency, the iron weight could be removed by unscrewing the heads of the bolts from inside the vessel.

Hunley was equipped with two watertight hatches, one forward and one aft, atop two short conning towers equipped with small portholes and slender, triangular cutwaters. The hatches, bigger than original estimates, measure about 16.5 in (420 mm) wide and nearly 21 in (530 mm) long),[8] making entrance to and egress from the hull difficult. The height of the ship's hull was 4 feet 3 inches (1.30 m).

By July 1863, Hunley was ready for a demonstration. Supervised by Confederate Admiral Franklin Buchanan, Hunley successfully attacked a coal flatboat in Mobile Bay. Following this, the submarine was shipped by rail to Charleston, South Carolina, arriving on 12 August 1863.

However, the Confederate military seized the submarine from her private builders and owners shortly after arriving, turning her over to the Confederate Army. Hunley would operate as a Confederate Army vessel from then on, although Horace Hunley, and his partners would remain involved in her further testing and operation. While sometimes referred to as CSS Hunley, she was never officially commissioned into service.

Confederate Navy Lieutenant John A. Payne of CSS Chicora volunteered to be Hunley's captain, and seven men from Chicora and CSS Palmetto State volunteered to operate her. On 29 August 1863, Hunley's new crew was preparing to make a test dive, when Lieutenant Payne accidentally stepped on the lever controlling the sub's diving planes as she was running on the surface. This caused Hunley to dive with one of her hatches still open. Payne and two others escaped, but the other five crewmen drowned.

H. L. Hunley crew lost 29 August 1863:[9]

- Michael Cane

- Nicholas Davis

- Frank Doyle

- John Kelly

- Absolum Williams

The Confederate Army took control of Hunley, with all orders coming directly from General P. G. T. Beauregard, with Lt. George E. Dixon placed in charge. On 15 October 1863, Hunley failed to surface after a mock attack, killing all eight crewmen. Among these was Hunley himself, who had joined the crew for the exercise and possibly had taken over command from Dixon, for the attack maneuver. The Confederate Navy once more salvaged the submarine and returned her to service.

H. L. Hunley Crew lost 15 October 1863:[10]

- Horace Hunley.

- Thomas S. Parks

- Henry Beard.

- R. Brookbanks

- John Marshall

- Charles McHugh

- Joseph Patterson

- Charles L. Sprague

Armament

Hunley was originally intended to attack by using a floating explosive charge with a contact fuse (a torpedo in 19th century terminology) which was towed at the end of a long rope. Hunley was to approach an enemy ship on the surface, then dive under her, and surface again once beyond her. The torpedo would be drawn against the targeted ship and explode. This plan was discarded as dangerous because of the possibility of the tow line fouling Hunley's screw or drifting into the submarine herself.

Instead, a spar torpedo—a copper cylinder containing 135 pounds (61 kilograms) of black powder—was attached to a 22-foot (6.7 m)-long wooden spar, as seen in illustrations made at this time. Mounted on Hunley's bow, the spar was to be used when the submarine was 6 ft (1.8 m) or more below the surface. Previous spar torpedoes had been designed with a barbed point: the spar torpedo would be jammed in the target's side by ramming, and then detonated by a mechanical trigger attached to the submarine by a line, so that as she backed away from her target, the torpedo would set off. However, archaeologists working on Hunley discovered evidence, including a spool of copper wire and components of a battery, that it may actually have been electrically detonated. In the configuration used in the attack on Housatonic, it appears Hunley's torpedo had no barbs, and was designed to explode on contact as it was pushed against an enemy vessel at close range.[11] After Horace Hunley's death, General Beauregard ordered that the submarine should no longer be used to attack underwater. An iron pipe was then attached to her bow, angled downwards so the explosive charge would be delivered sufficiently under water to make it effective. This was the same method developed for the earlier "David" surface attack craft used successfully against the USS New Ironsides. The Confederate Veteran of 1902, printed a reminiscence authored by an engineer stationed at Battery Marshall who, with another engineer, made adjustments to the iron pipe mechanism before Hunley left on her last fatal mission on 17 February 1864. A drawing of the iron pipe spar, confirming her "David" type configuration, was published in early histories of submarine warfare.

Attack on Housatonic

Hunley made her only attack against an enemy target on the night of 17 February 1864. The target was USS Housatonic, a 1,240 long tons (1,260 t)[2] wooden-hulled steam-powered sloop-of-war with 12 large cannons, which was stationed at the entrance to Charleston, about 5 miles (8.0 kilometres) offshore. Desperate to break the naval blockade of the city, Lieutenant George E. Dixon, and a crew of seven volunteers successfully attacked Housatonic, ramming Hunley's only spar torpedo against the enemy's hull.[12] The torpedo was detonated, sending Housatonic to the bottom in five minutes, along with five of her crewmen.[13]

Years later, when the area around the wreck of Housatonic was surveyed, the sunken Hunley was found on the seaward side of the sloop, where no one had considered looking before. This later indicated that the ocean current was going out following the attack on Housatonic, taking Hunley with her to where she was eventually found and later recovered.

Disappearance

After the attack, H.L. Hunley failed to return to her base. At one point there appeared to be evidence that Hunley survived as long as one hour following the attack at about 20:45. The day after the attack, the commander of "Battery Marshall" reported that he had received "the signals" from the submarine indicating she was returning to her base.[14] The report did not say what the signals were. A postwar correspondent wrote that "two blue lights" were the prearranged signals,[15] and a lookout on Housatonic reported he saw a "blue light" on the water after his ship sank.[16] "Blue light" in 1864 referred to a pyrotechnic signal[17] in long use by the U.S. Navy.[18] It has been falsely represented in published works as a blue lantern; the lantern eventually found on the recovered H. L. Hunley had a clear, not a blue, lens.[19] Pyrotechnic "blue light" could be seen easily over the (four-mile (six-point-four-kilometre)) distance between Battery Marshall and the site of Hunley's attack on Housatonic.[20]

After signaling, Dixon's plan would have been to take his submarine underwater to make a return to Sullivan's Island. Although at one point the finders of Hunley suggested she was unintentionally rammed by USS Canandaigua when that warship was going to rescue the crew of Housatonic, no such damage was found when she was raised from the bottom of the harbor. Instead, all evidence and analysis eventually pointed to the instantaneous death of Hunley's entire crew at the moment of the spar torpedo's contact with the hull of Housatonic from the explosion's shock wave which destroyed their lungs and brain tissue in milliseconds. In October 2008, scientists reported they had found that the crew of Hunley had not set her pump to remove water from the crew's compartment, and this might indicate she was not being flooded. In January 2013, it was announced that conservator Paul Mardikian, had found evidence of a copper sleeve at the end of Hunley's spar. This indicated the torpedo had been attached directly to the spar, meaning the submarine may have been less than 20 feet from Housatonic when the torpedo exploded.[3] The short distance involved has led some researchers to theorize that Hunley's crew was killed by the resulting blast,[21] though their conclusion has been disputed by US Navy and Naval History and Heritage Command researchers.[22] In 2018, researchers reported that the keel blocks, which would allow the sub to surface quickly in an emergency, had never been released.[23]

Recovery of wreckage

Hunley's discovery was described by Dr. William Dudley, Director of Naval History at the Naval Historical Center as "probably the most important find of the century."[24] The tiny sub and her contents have been valued at more than $40 million, making her discovery and subsequent donation one of the most important and valuable contributions made to South Carolina.

.jpg)

The discovery of Hunley has been claimed by two different individuals. Underwater Archaeologist E. Lee Spence, president, Sea Research Society, reportedly discovered Hunley in 1970,[25][26] and has a collection of evidence[27] claiming to validate this, including a 1980 Civil Admiralty Case.[28] The court took the position that the wreck was outside the jurisdiction of the U.S. Marshals Office, and no determination of ownership was made.[29]

On 13 September 1976, the National Park Service submitted Sea Research Society's (Spence's) location for H. L. Hunley for inclusion on the National Register of Historic Places. Spence's location for Hunley became a matter of public record when H. L. Hunley's placement on that list was officially approved on 29 December 1978.[30] Spence's book Treasures of the Confederate Coast, which had a chapter on his discovery of Hunley and included a map complete with an "X" showing the wreck's location, was published in January 1995.[31]

Diver Ralph Wilbanks located the wreck in April 1995, while leading a NUMA dive team originally organized by archaeologist Mark Newell, and funded by novelist Clive Cussler,[32] who announced the find as a new discovery[33] and first claimed that the location was in about 18 ft (5.5 m) of water over a mile inshore of Housatonic, but later admitted to a reporter that that was false.[34] The wreck was actually 100 yd (91 m) away from and on the seaward side of Housatonic in 27 feet (8.2 m) of water. The submarine was buried under several feet of silt, which had both concealed and protected the vessel for more than a hundred years. The divers exposed the forward hatch and the ventilator box (the air box for the attachment of her twin snorkels) in order to identify her. The submarine was resting on her starboard side, at about a 45-degree angle, and was covered in a 1⁄4 to 3⁄4 inch (0.64 to 1.91 cm) thick encrustation of rust bonded with sand and seashell particles. Archaeologists exposed part of the ship's port side and uncovered the bow dive plane. More probing revealed an approximate length of 37 feet (11 m), with all of the vessel preserved under the sediment.[35]

On 14 September 1995, at the official request of Senator Glenn F. McConnell, Chairman, South Carolina Hunley Commission,[36] E. Lee Spence, with South Carolina Attorney General Charles M. Condon signing, donated[37] Hunley to the State of South Carolina.[38][39] Shortly thereafter, NUMA disclosed to government officials Wilbank's location for the wreck which, when finally made public in October 2000, matched Spence's 1970s plot of the wreck's location well within standard mapping tolerances.[40] Spence avows that he discovered Hunley in 1970, revisiting and mapping the site in 1971 and again in 1979, and that after he published the location in his 1995 book he expected NUMA to independently verify the wreck as Hunley, not to claim that NUMA had discovered her. NUMA was actually part of a SCIAA expedition directed by Dr. Mark M. Newell and not Cussler.[41][42]) Dr. Newell swore under oath that he used Spence's maps to direct the joint SCIAA/NUMA expedition and credited Spence with the original discovery. Dr. Newell credits his expedition only with the official verification of Hunley.[43]

The in situ underwater archaeological investigation and excavation culminated with the raising of Hunley on 8 August 2000.[44] A large team of professionals from the Naval Historical Center's Underwater Archaeology Branch, National Park Service, the South Carolina Institute of Archaeology and Anthropology, and various other individuals investigated the vessel, measuring and documenting her prior to removal. Once the on-site investigation was complete, harnesses were slipped underneath the sub and attached to a truss designed by Oceaneering International. After the last harness had been secured, the crane from the recovery barge Karlissa B hoisted the submarine from the sea floor.[45][46] She was raised from the open waters of the Atlantic Ocean, just over 3.5 nautical miles (6.5 km) from Sullivan's Island outside the entrance to Charleston Harbor. Despite having used a sextant and hand-held compass, thirty years earlier, to plot the wreck's location, Dr. Spence's 52 m (171 ft) accuracy turned out to be well within the length of the recovery barge, which was 64 m (210 ft) long.[47][48] On 8 August 2000, at 08:37, the sub broke the surface for the first time in more than 136 years, greeted by a cheering crowd on shore and in surrounding watercraft, including author Clive Cussler. Once safely on her transporting barge, Hunley was shipped back to Charleston. The removal operation concluded when the submarine was secured inside the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, at the former Charleston Navy Yard in North Charleston, in a specially designed tank of fresh water to await conservation until she could eventually be exposed to air.

The exploits of Hunley and her final recovery were the subject of an episode of the television series The Sea Hunters, called Hunley: First Kill. This program was based on a section ("Part 6") in Clive Cussler's 1996 non-fiction book of the same name (which was accepted by the Board of Governors of the Maritime College of the State University of New York in lieu of his Ph.D. thesis).[49]

In 2001, Clive Cussler, filed a lawsuit against E. Lee Spence, for unfair competition, injurious falsehood, civil conspiracy, and defamation.[50] Spence filed a countersuit against Cussler, in 2002, seeking damages, claiming that Cussler was engaging in unfair competition, tortious interference, and civil conspiracy by claiming Cussler had discovered the location of the wreck of Hunley in 1995, when she had already been discovered by Spence in 1970, and that such claims by Cussler were damaging to Spence's career, and had caused him damages in excess of $100,000.[51] Spence's lawsuit was dismissed through summary judgment in 2007, on the legal theory that, under the Lanham Act, regardless of whether Cussler's claims were factual or not, Cussler had been making them for over three years before Spence brought his suit against Cussler, and thus the suit was not filed within the statute of limitations.[52] Cussler dropped his suit a year later,[53] after the judge agreed that Spence could introduce evidence in support of his discovery claims as a truth defense against Cussler's claims against him.[54]

Hunley may be viewed during tours at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, in Charleston. A replica is on display at Battleship Memorial Park, Mobile, Alabama, alongside the USS Alabama (BB-60) and the USS Drum (SS-228).

Crew

The crew was composed of Lieutenant George E. Dixon (Commander) (of Alabama or Ohio), Frank Collins (of Virginia), Joseph F. Ridgaway (of Maryland), James A. Wicks (North Carolina native living in Florida), Arnold Becker (of Germany), Corporal Johan Frederik Carlsen (of Denmark), C. Lumpkin (probably of the British Isles), and Augustus Miller (probably a former member of the German Artillery).[55][56][57]

Apart from the commander of the submarine, Lieutenant George E. Dixon, the identities of the volunteer crewmen of Hunley had long remained a mystery. Douglas Owsley, a physical anthropologist working for the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of Natural History, examined the remains and determined that four of the men were American born, while the four others were of European birth, based on the chemical signatures left on the men's teeth and bones by the predominant components of their diet. Four of the men had eaten plenty of corn, an American diet, while the remainder ate mostly wheat and rye, a mainly European one. By examining Civil War records and conducting DNA testing with possible relatives, forensic genealogist Linda Abrams, was able to identify the remains of Dixon, and the three other Americans: Frank G. Collins of Fredericksburg, Va., Joseph Ridgaway, and James A. Wicks.[19] Identifying the European crewmen has been more problematic, but was apparently solved in late 2004. The position of the remains indicated that the men died at their stations and were not trying to escape from the sinking submarine.[21]

On 17 April 2004, the remains of the crew were laid to rest at Magnolia Cemetery, in Charleston.[58] Tens of thousands of people attended including some 6,000 reenactors and 4,000 civilians wearing period clothing. Color guards from all five branches of the U.S. armed forces—wearing modern uniforms—were also in the procession.[59] Even though only two of the crew were from the Confederate States, all were buried with full Confederate honors, including being buried with the 2nd Confederate national flag,[60] known as the Stainless Banner.

Another surprise occurred in 2002, when lead researcher Maria Jacobsen,[61][62] examining the area close to Lieutenant Dixon, found a misshapen $20 gold piece, minted in 1860, with the inscription "Shiloh April 6, 1862 My life Preserver G. E. D." on a sanded-smooth area of the coin's reverse side, and a forensic anthropologist found a healed injury to Lt. Dixon's hip bone. The findings matched a legend, passed down in the family, that Dixon's sweetheart, Queenie Bennett, had given him the coin to protect him. However, the supposed relationship between Bennett and Dixon, has not been supported by archaeological investigation of the legend. Dixon had the coin with him at the Battle of Shiloh, where he was wounded in the thigh on 6 April 1862. The bullet struck the coin in his pocket, saving his leg and possibly his life. He had the gold coin engraved and carried it as a lucky charm.[63][64]

A.J. Kronegh, of the Danish National Archive, has identified the J.F. Carlsen of Hunley. Johan F. Carlsen, was born in Ærøskøbing 9 April 1841. The last year he is registered in the census of Ærøskøbing is 1860, where he is registered as "sailor". The teeth of his remains in Hunley still bear significant marks of a cobbler, which was the profession of his father. In 1861, J.F. Carlsen entered the freight ship Grethe of Dragør, which landed in Charleston, in February 1861, where J.F. Carlsen left (deserted) the ship. In June 1861, he entered Jefferson Davis (the Confederate privateer brig originally named Putnam) as mate.[65][66]

Tours

Visitors can obtain tickets for guided tours of the conservation laboratory that houses Hunley, at the Warren Lasch Conservation Center, on weekends. The actual Hunley is preserved and on display in a tank of water, while a replica can be entered by the public. The Center includes artifacts found inside Hunley, exhibits about the submarine and a video.

In popular culture

- Hunley's story was the subject of the first episode (entitled "The Hunley") of the TV series The Great Adventure. It aired on 27 September 1963, on CBS. The role of Lt. Dixon (misspelled in the credits as "Lt. Dickson") was played by Jackie Cooper.

- The original TNT Network made-for-cable movie The Hunley (1999) tells the story of H. L. Hunley's final mission while on station in Charleston. It stars Armand Assante, as Lt. Dixon, and Donald Sutherland, as General Beauregard, Dixon's direct superior on the Hunley project.[67]

- Hunley is the inspiration of the Sons of Confederate Veterans, H. L. Hunley JROTC Award, presented to cadets on the basis of strong corps values, honor, courage, and commitment to their unit during the school year.[68]

- In the novel The Stingray Shuffle by Tim Dorsey, a minor drug cartel decides to emulate the larger cartels' narco-submarine cocaine trafficking by building a replica of Hunley using blueprints downloaded off the Internet.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to H. L. Hunley (submarine, 1863). |

- USS Alligator (1862) – U. S. Navy submarine launched a year before Hunley

- The American Turtle – built in 1775, the world's first submersible with a documented record of use in combat

- French submarine Plongeur – launched a few months before Hunley

- Peral Submarine – 1888 submarine from Spain, the first to be powered by electric batteries

References

Citations

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Housatonic Archived copy at the Library of Congress (December 5, 2013).

- Smith, Bruce (January 28, 2013). "Experts find new evidence in submarine mystery". Associated Press. Retrieved January 29, 2013.

- Walker, Sally M. (2005). Secrets of a Civil War Submarine: Solving the Mysteries of the H. L. Hunley. Minneapolis: Carolrhoda Books. pp. 10, 11. ISBN 9781575058306.

- Early, Curtis A.; Early, Gloria J. (2011). Ohio Confederate Connection: Facts You May Not Know about the Civil War. Bloomington, IN: iUniverse. p. 218. ISBN 9781450273732.

- John S. Sledge (29 May 2015). The Mobile River. University of South Carolina Press. pp. 188–189. ISBN 978-1-61117-486-1.

- "Hunley Newsletter #66". August–September 2006. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04.

- Find a grave virtual cemetery

- Civil War Forum

- Brian Hicks (27 January 2013). "Rewriting history: Discovery alters legend of doomed sub..." The Post and Courier.

- Lance, Rachel M.; Stalcup, Lucas; Wojtylak, Brad; Bass, Cameron R. (2017). "Air blast injuries killed the crew of the submarine H.L. Hunley". PLoS ONE. 12 (8): e0182244. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1282244L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182244. PMC 5568114. PMID 28832592.

- The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion Series I – Vol. 15, p. 328

- The Official Records of the Union and Confederate Navies in the War of the Rebellion; Series I – Vol. 15, p. 335.

- Jacob N. Cardozo, Reminiscences of Charleston (Charleston, 1866) p. 124

- Proceedings of the Naval Court of Inquiry on the Sinking of the Housatonic NARA Microfilm Publication M 273, reel 169, Records of the Judge Advocate General (Navy) Record Group 125

- Noah Webster, International Dictionary of the English Language Comprising the issues of 1864, 1879 and 1884, ed. Noah Porter, p. 137.

- George Marshall, Marshall’s Practical Marine Gunnery: Containing a View of the Magnitude, Weight, Description and Use of Every Article Used in the Sea Gunner’s Department in the Navy of the United States (Norfolk, 1822), pp. 22 and 24.

- Tom Chaffin (16 February 2010). The H. L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. pp. 225–242. ISBN 978-1-4299-9035-6.

- Benton, Captain James Gilchrist (1862). A Course of Instruction in Ordnance and Gunnery Compiled for the Use of the Cadets of the United States Military Academy (Second ed.). p. 369.

- Lance, Rachel M.; Stalcup, Lucas; Wojtylak, Brad; Bass, Cameron R. (2017-08-23). "Air blast injuries killed the crew of the submarine H.L. Hunley". PLoS ONE. 12 (8): e0182244. Bibcode:2017PLoSO..1282244L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0182244. PMC 5568114. PMID 28832592.

- "Black Powder Blast Effects on the Confederate Submarine Hunley". Naval History and Heritage Command. 28 August 2017. Retrieved 2018-03-14.

- "Clues to Confederate Mystery: Sub's Crew Never Dumped Weight". New York Times. Associated Press. July 18, 2018.

- "H.L. Hunley Fact Sheet". The Hunley. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03.CS1 maint: unfit url (link)

- Curry, Andrew (June 24, 2007). "A Civil War Time Capsule From the Sea: Artifacts from the South's submarine are turning fable into fact". U.S. News & World Report.

- Roberts, Nancy (2001). "The Man Who Found the Hunley: Charleston, South Carolina". Ghosts from the Coast. UNC Press. pp. 89–94. ISBN 978-0-8078-2665-2.

- "Letters, Charts, Maps, Documents, etc. attached to Dr. E. Lee Spence's Sworn Affidavit regarding Spence's 1970 discovery of the Civil War submarine H.L. Hunley". Shipwrecks.com. Archived from the original on 2008-02-28.

- United States District Court, District of Charleston, Case #80-1303-8, Filed July 8, 1980

- Witte, Sully (Sep 5, 2015). "A look back at Hurricane Hugo, five years after the storm". Moultrie News. Evening Post Industries. Archived from the original on 7 July 2019. Retrieved 13 December 2017.

- Yasko, Karel (February 1976). "H. L. Hunley (Submarine)" (PDF). National Register of Historic Places Nomination Form - Inventory. National Park Service. Retrieved 28 April 2012.

- Treasures of the Confederate Coast: The "Real Rhett Butler" & Other Revelations by Dr. E. Lee Spence, Narwhal Press, Charleston/Miami, © 1995, p.54

- Raising the Hunley: The Remarkable History and Recovery of the Lost Confederate Submarine by B. Hicks and S. Kropf, Ballantine Publishing, NY, © 2002, p. 131

- NUMA News release, Austin, Texas, May 11, 1995

- "Salvaging Hunley clues: Cussler fibs about sub's depth" by Schuyler Kropf, The Post and Courier, Charleston, SC, May 11, 1996

- H.L. Hunley Site Assessment, NPS, NHC and SCIAA, edited by Larry Murphy (SCRU), 1998, pp. 6–13, 63–66

- Minutes of the Hunley Commission Meeting of September 14, 1995

- "Wayback Machine". 15 January 2003. Archived from the original on 15 January 2003. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- "Assignment of Interest," September 14, 1995, signed by E. Lee Spence and Charles Molony Condon, Attorney General State of South Carolina

- "Hunley claimant signs over rights to state" by Sid Gaulden, The Post and Courier, Charleston, SC, September 15, 1995

- 'Whose X marks the spot?' by W. Thomas Smith Jr., Charleston City Paper, Charleston, SC, October 4, 2000, p. 16

- "News," official press release by NUMA, listing Clive Cussler as a contact, Austin, Texas, May 11, 1995

- The Hunley: Submarines, Sacrifice & Success in the Civil War by Mark Ragan, Narwhal Press Inc., ISBN 1-886391-04-1, p. 186

- The Andy Thomas Show, live radio interview by Andy Thomas with Dr. Newell, Dr. Spence and Claude Petrone, Columbia, SC, August, 2001

- Neyland, Robert S (2005). "Underwater Archaeology and the Confederate Submarine H.L. Hunley". In: Godfrey, JM; Shumway, SE. Diving for Science 2005. Proceedings of the American Academy of Underwater Sciences Symposium on March 10–12, 2005 at the University of Connecticut at Avery Point, Groton, Connecticut. American Academy of Underwater Sciences. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- "Tubería y Perfiles PROLAMSA" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-15.

- Teaster, Gerald. "Karlissa B Crane".

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120228203228/http://www.titansalvage.com/jackupbarges/jackupspecs.pdf

- "Annotated section of November 24, 1979, edition of NOAA chart 11523 with Spence's 1980 claim area and showing sites marked "it" which is the wreck of the Civil War submarine H.L. Hunley and "W.O," which is the old Housatonic wreck buoy". Archived from the original on July 4, 2008.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- The Arizona Republic, May 18, 1997; page unknown, dated cut-out article

- Bruce Smith (October 11, 2001). "H.L. Hunley Discovery Case Heads to Court". The Item. Associated Press.

- Civil Action Number 2:01-cv-04006-SB, Date Filed 05/31/2002, entry number 35, pages 32–40

- "Judge dismisses counterclaim in Hunley lawsuit". HistoryNet.com. The Associated Press. May 18, 2007. Archived from the original on January 15, 2015.

- Kropf, Schuyler. "Cussler ends lawsuit over finding Hunley".

- Civil Action Number 2:01-cv-04006-SB, Date Filed 06/06/08, Entry Number 209, Page 8 of 30

- Willie Drye (April 12, 2004). "Hunley Findings Put Faces on Civil War Submarine". National Geographic News. p. 2. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- Associated Press (24 August 2017). "Crew of Hunley studied". The Augusta Chronicle. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- find a grave (24 August 2017). "Smn Augustus Miller". Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- "Friends of the Hunley". hunley.org. Archived from the original on 27 July 2003. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- "Last Funeral of the Civil War" to Put Hunley Crew to Rest (dead link 25 February 2020)

- "Last Funeral of the Civil War" to Put Hunley Crew to Rest (dead link 25 February 2020)

- Tayler, Jeffrey. "Secret Weapon of the Confederacy" National Geographic (magazine), July 2002. Accessed: December 22, 2014.

- "Secret Weapon of the Confederacy" IMDb, September 15, 2011. Accessed: December 22, 2014.

- Ron Franscell (November 18, 2002). "Civil War legends surface with sub Fort Collins expert studies exhumed sailors". The Denver Post. p. A1.

- "The Legend of the gold coin". hunley.org. Archived from the original on 11 August 2002. Retrieved 26 September 2017.

- "Press release: J. F. Carlsen from the Hunley identified". Danish National Archive. 28 September 2015.

- "Mysteriet om den 8. mand" [The Mystery of the 8th Man]. Berlingske (in Danish). 27 September 2015.

- "The Hunley". 11 July 1999. Retrieved 26 September 2017 – via www.imdb.com.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-16. Retrieved 2010-05-11.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

Bibliography

- The H. L. Hunley: The Secret Hope of the Confederacy by Tom Chaffin (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2008), ISBN 0-8090-9512-2

- The Hunley: Submarines, Sacrifice & Success in the Civil War by Mark Ragan (Narwhal Press, Charleston/Miami, 1995), ISBN 1-886391-43-2

- Ghosts from the Coast, "The Man Who Found the Hunley" by Nancy Roberts, UNC Press, 2001, ISBN 978-0-8078-2665-2

- Treasures of the Confederate Coast: the "real Rhett Butler" & Other Revelations by Dr. E. Lee Spence, (Narwhal Press, Charleston/Miami, 1995), ISBN 1-886391-00-9

- Civil War Sub ISBN 0-448-42597-1

- The Voyage of the Hunley, ISBN 1-58080-094-7

- Raising the Hunley, ISBN 0-345-44772-7

- The CSS H. L. Hunley, ISBN 1-57249-175-2

- The CSS Hunley, ISBN 0-87833-219-7

- Shipwreck Encyclopedia of the Civil War: South Carolina & Georgia, 1861–1865 by Edward Lee Spence (Sullivan's Island, S. C., Shipwreck Press, 1991) OCLC: 24420089

- Shipwrecks of South Carolina and Georgia: (includes Spence's List, 1520–1865) Sullivan's Island, S. C. (Sullivan's Island 29482, Sea Research Society, 1984)OCLC 10593079

- Shipwrecks of the Civil War : Charleston, South Carolina, 1861–1865 map by E. Lee Spence (Sullivan's Island, S. C., 1984) OCLC 11214217

- Robert F. Burgess (1975). Ships Beneath the Sea: A History of Subs and Submersibles. New York: McGraw Hill. p. 238.

- Crawford, Thomas A. (June 2018). "Why Did H. L. Hunley Sink?". Warship International. LV (2): 165–166. ISSN 0043-0374.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to H. L. Hunley. |

- US Navy at the Wayback Machine (archived 2003-12-25)

- Friends of the Hunley – includes visiting information

- Sea Research Society links to Hunley at the Wayback Machine (archived 2006-06-13)

- "H. L. Hunley, Confederate Submarine" at the U.S. Naval Historical Center at the Library of Congress Web Archives (archived 2010-04-07)

- Pre-Hunley – Confederate Submarines

- The Hunley (TV movie)

- Rootsweb

- Hunley – Archaeological Interpretation and 3D Reconstruction

- Hunley Related Items at the Wayback Machine (archived 2003-02-04)

- HNSA Web Page: H.L. Hunley at the Wayback Machine (archived 2007-10-14)

- H.L. Hunley article, Encyclopedia of Alabama

- An Interview with Dr. Lee Spence – Discoverer of the Confederate Submarine HL Hunley