Greenland ice sheet

The Greenland ice sheet (Danish: Grønlands indlandsis, Greenlandic: Sermersuaq) is a vast body of ice covering 1,710,000 square kilometres (660,000 sq mi), roughly 79% of the surface of Greenland.

| Greenland ice sheet | |

|---|---|

| Grønlands indlandsis Sermersuaq | |

| Type | Ice sheet |

| Coordinates | 76°42′N 41°12′W |

| Area | 1,710,000 km2 (660,000 sq mi) |

| Length | 2,400 km (1,500 mi) |

| Width | 1,100 km (680 mi) |

| Thickness | 2,000–3,000 m (6,600–9,800 ft) |

It is the second largest ice body in the world, after the Antarctic ice sheet. The ice sheet is almost 2,900 kilometres (1,800 mi) long in a north-south direction, and its greatest width is 1,100 kilometres (680 mi) at a latitude of 77°N, near its northern margin. The mean altitude of the ice is 2,135 metres (7,005 ft).[1] The thickness is generally more than 2 km (1.2 mi) and over 3 km (1.9 mi) at its thickest point. In addition to the large ice sheet, isolated glaciers and small ice caps cover between 76,000 and 100,000 square kilometres (29,000 and 39,000 sq mi) around the periphery. If the entire 2,850,000 cubic kilometres (684,000 cu mi) of ice were to melt, it would lead to a global sea level rise of 7.2 m (24 ft).[2] The Greenland Ice Sheet is sometimes referred to under the term inland ice, or its Danish equivalent, indlandsis. It is also sometimes referred to as an ice cap.

General

The presence of ice-rafted sediments in deep-sea cores recovered from northwest Greenland, in the Fram Strait, and south of Greenland indicated the more or less continuous presence of either an ice sheet or ice sheets covering significant parts of Greenland for the last 18 million years. From about 11 million years ago to 10 million years ago, the Greenland Ice Sheet was greatly reduced in size. The Greenland Ice Sheet formed in the middle Miocene by coalescence of ice caps and glaciers. There was an intensification of glaciation during the Late Pliocene.[3] Ice sheet formed in connection to the uplift of the West Greenland and East Greenland uplands. The Western and Eastern Greenland mountains constitute passive continental margins that were uplifted in two phases, 10 and 5 million years ago, in the Miocene epoch.[upper-alpha 1] Computer modelling shows that the uplift would have enabled glaciation by producing increased orographic precipitation and cooling the surface temperatures.[4] The oldest known ice in the current ice sheet is as much as 1,000,000 years old.[5]

The weight of the ice has depressed the central area of Greenland; the bedrock surface is near sea level over most of the interior of Greenland, but mountains occur around the periphery, confining the sheet along its margins. If the ice suddenly disappeared, Greenland would most probably appear as an archipelago, at least until isostasy lifted the land surface above sea level once again. The ice surface reaches its greatest altitude on two north-south elongated domes, or ridges. The southern dome reaches almost 3,000 metres (10,000 ft) at latitudes 63°–65°N; the northern dome reaches about 3,290 metres (10,800 ft) at about latitude 72°N (the fourth highest "summit" of Greenland). The crests of both domes are displaced east of the centre line of Greenland. The unconfined ice sheet does not reach the sea along a broad front anywhere in Greenland, so that no large ice shelves occur. The ice margin just reaches the sea, however, in a region of irregular topography in the area of Melville Bay southeast of Thule. Large outlet glaciers, which are restricted tongues of the ice sheet, move through bordering valleys around the periphery of Greenland to calve off into the ocean, producing the numerous icebergs that sometimes occur in North Atlantic shipping lanes. The best known of these outlet glaciers is Jakobshavn Glacier (Greenlandic: Sermeq Kujalleq), which, at its terminus, flows at speeds of 20 to 22 metres or 66 to 72 feet per day.

On the ice sheet, temperatures are generally substantially lower than elsewhere in Greenland. The lowest mean annual temperatures, about −31 °C (−24 °F), occur on the north-central part of the north dome, and temperatures at the crest of the south dome are about −20 °C (−4 °F).

Change of the ice sheet

The ice sheet as a record of past climates

The ice sheet, consisting of layers of compressed snow from more than 100,000 years, contains in its ice today's most valuable record of past climates. In the past decades, scientists have drilled ice cores up to 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) deep. Scientists have, using those ice cores, obtained information on (proxies for) temperature, ocean volume, precipitation, chemistry and gas composition of the lower atmosphere, volcanic eruptions, solar variability, sea-surface productivity, desert extent and forest fires. This variety of climatic proxies is greater than in any other natural recorder of climate, such as tree rings or sediment layers.

The melting ice sheet

Summary

Many scientists who study the ice ablation in Greenland consider that an increase in temperature of two or three degrees Celsius would result in a complete melting of Greenland's ice and leave Greenland completely submerged in water.[6] Positioned in the Arctic, the Greenland ice sheet is especially vulnerable to climate change. Arctic climate is believed to be now rapidly warming and much larger Arctic shrinkage changes are projected.[7] The Greenland Ice Sheet has experienced record melting in recent years since detailed records have been kept and is likely to contribute substantially to sea level rise as well as to possible changes in ocean circulation in the future. The area of the sheet that experiences melting has been argued to have increased by about 16% between 1979 (when measurements started) and 2002 (most recent data). The area of melting in 2002 broke all previous records.[7] The number of glacial earthquakes at the Helheim Glacier and the northwest Greenland glaciers increased substantially between 1993 and 2005.[8] In 2006, estimated monthly changes in the mass of Greenland's ice sheet suggest that it is melting at a rate of about 239 cubic kilometers (57 cu mi) per year. A more recent study, based on reprocessed and improved data between 2003 and 2008, reports an average trend of 195 cubic kilometers (47 cu mi) per year.[9] These measurements came from the US space agency's GRACE (Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment) satellite, launched in 2002, as reported by BBC.[10] Using data from two ground-observing satellites, ICESAT and ASTER, a study published in Geophysical Research Letters (September 2008) shows that nearly 75 percent of the loss of Greenland's ice can be traced back to small coastal glaciers.[11]

If the entire 2,850,000 km3 (684,000 cu mi) of ice were to melt, global sea levels would rise 7.2 m (24 ft).[2] Recently, fears have grown that continued climate change will make the Greenland Ice Sheet cross a threshold where long-term melting of the ice sheet is inevitable.[12][13] Climate models project that local warming in Greenland will be 3 °C (5 °F) to 9 °C (16 °F) during this century. Ice sheet models project that such a warming would initiate the long-term melting of the ice sheet, leading to a complete melting of the ice sheet (over centuries), resulting in a global sea level rise of about 7 metres (23 ft).[7] Such a rise would inundate almost every major coastal city in the world. How fast the melt would eventually occur is a matter of discussion. According to the IPCC 2001 report,[2] such warming would, if kept from rising further after the 21st Century, result in 1 to 5 meter sea level rise over the next millennium due to Greenland ice sheet melting. Some scientists have cautioned that these rates of melting are overly optimistic as they assume a linear, rather than erratic, progression. James E. Hansen has argued that multiple positive feedbacks could lead to nonlinear ice sheet disintegration much faster than claimed by the IPCC. According to a 2007 paper, "we find no evidence of millennial lags between forcing and ice sheet response in paleoclimate data. An ice sheet response time of centuries seems probable, and we cannot rule out large changes on decadal time-scales once wide-scale surface melt is underway."[14]

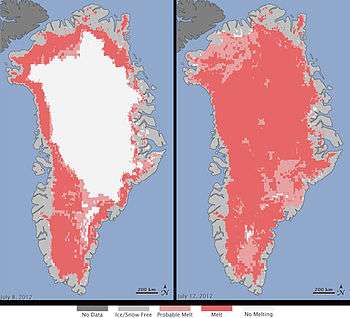

The melt zone, where summer warmth turns snow and ice into slush and melt ponds of meltwater, has been expanding at an accelerating rate in recent years. When the meltwater seeps down through cracks in the sheet, it accelerates the melting and, in some areas, allows the ice to slide more easily over the bedrock below, speeding its movement to the sea. Besides contributing to global sea level rise, the process adds freshwater to the ocean, which may disturb ocean circulation and thus regional climate.[7] In July 2012, this melt zone extended to 97 percent of the ice cover.[15] Ice cores show that events such as this occur approximately every 150 years on average. The last time a melt this large happened was in 1889. This particular melt may be part of cyclical behavior; however, Lora Koenig, a Goddard glaciologist suggested that "...if we continue to observe melting events like this in upcoming years, it will be worrisome."[16][17][18] Global warming is increasing growth of algae on the ice sheet. This darkens the ice causing it to absorb more sunlight and potentially increasing the rate of melting.[19]

Meltwater around Greenland may transport nutrients in both dissolved and particulate phases to the ocean.[20] Measurements of the amount of iron in meltwater from the Greenland ice sheet show that extensive melting of the ice sheet might add an amount of this micronutrient to the Atlantic Ocean equivalent to that added by airborne dust.[21] However much of the particles and iron derived from glaciers around Greenland may be trapped within the extensive fjords that surround the island[22] and, unlike the HNLC Southern ocean where iron is an extensive limiting micronutrient,[23] biological production in the North Atlantic is subject only to very spatially and temporally limited periods of iron limitation.[24] Nonetheless high productivity is observed in the immediate vicinity of major marine terminating glaciers around Greenland and this is attributed to meltwater inputs driving the upwelling of seawater rich in macronutrients.[25]

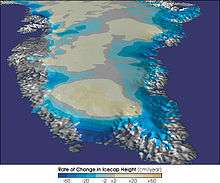

Until 2007, rate of decrease in ice sheet height in cm per year.

Until 2007, rate of decrease in ice sheet height in cm per year. Modelling results of the sea-level rise under different warming scenarios.

Modelling results of the sea-level rise under different warming scenarios. Satellite image of dark melt ponds.

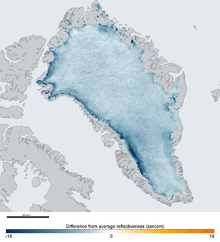

Satellite image of dark melt ponds. Albedo change in Greenland

Albedo change in Greenland

Observation and research since 2010

In a 2013 study published in Nature, 133 researchers analyzed a Greenland ice core from the Eemian interglacial. They concluded that during this geological period, roughly 130,000–115,000 years ago, the GIS (Greenland Ice Sheet) was 8 degrees C warmer than today. This resulted in a thickness decrease of the northwest Greenland ice sheet by 400 ± 250 metres, reaching surface elevations 122,000 years ago of 130 ± 300 metres lower than at present.[27]

Researchers have considered that clouds may enhance Greenland ice sheet melt. A study published in Nature in 2013 found that optically thin liquid-bearing clouds extended this July 2012 extreme melt zone,[28] while a Nature Communications study in 2016 suggests that clouds in general enhance Greenland ice sheet's meltwater runoff by more than 30% due to decreased meltwater refreezing in the firn layer at night.[29]

A 2015 study by climate scientists Michael Mann of Penn State and Stefan Rahmstorf from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research suggests that the observed cold blob in the North Atlantic during years of temperature records is a sign that the Atlantic Ocean's Meridional overturning circulation (AMOC) may be weakening. They published their findings, and concluded that the AMOC circulation shows exceptional slowdown in the last century, and that Greenland melt is a possible contributor.[30]

A study published in 2016, by researchers from the University of South Florida, Canada and the Netherlands, used GRACE satellite data to estimate freshwater flux from Greenland. They concluded that freshwater runoff is accelerating, and could eventually cause a disruption of AMOC in the future, which would affect Europe and North America.[31]

The United States built a secret nuclear powered base, called Camp Century, in the Greenland ice sheet.[32] In 2016, a group of scientists evaluated the environmental impact and estimated that due to changing weather patterns over the next few decades, melt water could release the nuclear waste, 20,000 liters of chemical waste and 24 million liters of untreated sewage into the environment. However, so far neither US or Denmark has taken responsibility for the clean-up.[33]

A 2018 international study found that the fertilizing effect of meltwater around Greenland is highly sensitive to the glacier grounding line depth it is released at. Retreat of Greenland's large marine-terminating glaciers inland will diminish the fertilizing effect of meltwater- even with further large increases in freshwater discharge volume.[34]

Melting process since 2000

- Between 2000 and 2001: Northern Greenland's Petermann glacier lost 85 square kilometres (33 sq mi) of floating ice.

- Between 2001 and 2005: Sermeq Kujalleq broke up, losing 93 square kilometres (36 sq mi) and raised awareness worldwide of glacial response to global climate change.[35]

- July 2008: Researchers monitoring daily satellite images discovered that a 28-square-kilometre (11 sq mi) piece of Petermann broke away.

- August 2010: A sheet of ice measuring 260 square kilometres (100 sq mi) broke off from the Petermann Glacier. Researchers from the Canadian Ice Service located the calving from NASA satellite images taken on August 5. The images showed that Petermann lost about one-quarter of its 70 km-long (43 mile) floating ice shelf.[36]

- July 2012: Another large ice sheet twice the area of Manhattan, about 120 square kilometres (46 sq mi), broke away from the Petermann glacier in northern Greenland.[37]

- In 2015, Jakobshavn Glacier calved an iceberg about 4,600 feet (1,400 m) thick with an area of about 5 square miles (13 km2).[6]

Two mechanisms have been utilized to explain the change in velocity of the Greenland Ice Sheets outlet glaciers. The first is the enhanced meltwater effect, which relies on additional surface melting, funneled through moulins reaching the glacier base and reducing the friction through a higher basal water pressure. (Not all meltwater is retained in the ice sheet and some moulins drain into the ocean, with varying rapidity.) This idea was observed to be the cause of a brief seasonal acceleration of up to 20% on Sermeq Kujalleq in 1998 and 1999 at Swiss Camp.[38] (The acceleration lasted between two and three months and was less than 10% in 1996 and 1997 for example. They offered a conclusion that the "coupling between surface melting and ice-sheet flow provides a mechanism for rapid, large-scale, dynamic responses of ice sheets to climate warming". Examination of recent rapid supra-glacial lake drainage documented short term velocity changes due to such events, but they had little significance to the annual flow of the large outlet glaciers.[39]

The second mechanism is a force imbalance at the calving front due to thinning causing a substantial non-linear response. In this case an imbalance of forces at the calving front propagates up-glacier. Thinning causes the glacier to be more buoyant, reducing frictional back forces, as the glacier becomes more afloat at the calving front. The reduced friction due to greater buoyancy allows for an increase in velocity. This is akin to letting off the emergency brake a bit. The reduced resistive force at the calving front is then propagated up-glacier via longitudinal extension because of the backforce reduction.[40][41] For ice streaming sections of large outlet glaciers (in Antarctica as well) there is always water at the base of the glacier that helps lubricate the flow.

If the enhanced meltwater effect is the key, then since meltwater is a seasonal input, velocity would have a seasonal signal and all glaciers would experience this effect. If the force imbalance effect is the key, then the velocity will propagate up-glacier, there will be no seasonal cycle, and the acceleration will be focused on calving glaciers. Helheim Glacier, East Greenland had a stable terminus from the 1970s–2000. In 2001–2005 the glacier retreated 7 km (4.3 mi) and accelerated from 20 to 33 m or 70 to 110 ft/day, while thinning up to 130 meters (430 ft) in the terminus region. Kangerdlugssuaq Glacier, East Greenland had a stable terminus history from 1960 to 2002. The glacier velocity was 13 m or 43 ft/day in the 1990s. In 2004–2005 it accelerated to 36 m or 120 ft/day and thinned by up to 100 m (300 ft) in the lower reach of the glacier. On Sermeq Kujalleq the acceleration began at the calving front and spread up-glacier 20 km (12 mi) in 1997 and up to 55 km (34 mi) inland by 2003.[42] On Helheim the thinning and velocity propagated up-glacier from the calving front. In each case the major outlet glaciers accelerated by at least 50%, much larger than the impact noted due to summer meltwater increase. On each glacier the acceleration was not restricted to the summer, persisting through the winter when surface meltwater is absent.

An examination of 32 outlet glaciers in southeast Greenland indicates that the acceleration is significant only for marine-terminating outlet glaciers—glaciers that calve into the ocean.[43] A 2008 study noted that the thinning of the ice sheet is most pronounced for marine-terminating outlet glaciers.[44] As a result of the above, all concluded that the only plausible sequence of events is that increased thinning of the terminus regions, of marine-terminating outlet glaciers, ungrounded the glacier tongues and subsequently allowed acceleration, retreat and further thinning.[43][45][46][47]

Warmer temperatures in the region have brought increased precipitation to Greenland, and part of the lost mass has been offset by increased snowfall. However, there are only a small number of weather stations on the island, and though satellite data can examine the entire island, it has only been available since the early 1990s, making the study of trends difficult. It has been observed that there is more precipitation where it is warmer, up to 1.5 meters per year on the southeast flank, and less precipitation or none on the 25–80 percent (depending on the time of year) of the island that is cooler.[48]

Rate of change

Several factors determine the net rate of growth or decline. These are

- Accumulation and melting rates of snow in the central parts

- Melting of surface snow and ice which then flows into moulins, falls and flows to bedrock, lubricates the base of glaciers, and affects the speed of glacial motion. This flow is implicated in accelerating the speed of glaciers and thus the rate of glacial calving.

- Melting of ice along the sheet's margins (runoff) and basal hydrology,

- Iceberg calving into the sea from outlet glaciers also along the sheet's edges

Explanation of accelerated glacial coastward movement and iceberg calving fails to consider another causal factor: increased weight of the central highland ice sheet. As the central ice sheet thickens, which it has for at least seven decades, its greater weight causes more horizontal outward force at the bedrock. This in turn appears to have increased glacial calving at the coasts. Visual evidence for increased central highland ice sheet thickness exists in the numerous aircraft that have made forced landings on the icecap since the 1940s. They landed on the surface and later disappeared under the ice.[49] A notable example is the Lockheed P-38F Lightning World War II fighter plane Glacier Girl that was exhumed from 268 feet of ice in 1992 and restored to flying condition after being buried for over 50 years. It was recovered by members of the Greenland Expedition Society after years of searching and excavation, eventually transported to Kentucky and restored to flying condition.[50]

The IPCC Third Assessment Report (2001) estimated the accumulation to 520 ± 26 Gigatonnes of ice per year, runoff and bottom melting to 297±32 Gt/yr and 32±3 Gt/yr, respectively, and iceberg production to 235±33 Gt/yr. On balance, the IPCC estimates −44 ± 53 Gt/yr, which means that the ice sheet may currently be melting.[2] Data from 1996 to 2005 shows that the ice sheet is thinning even faster than supposed by IPCC. According to the study, in 1996 Greenland was losing about 96 km3 or 23.0 cu mi per year in volume from its ice sheet. In 2005, this had increased to about 220 km3 or 52.8 cu mi a year due to rapid thinning near its coasts,[51] while in 2006 it was estimated at 239 km3 (57.3 cu mi) per year.[10] It was estimated that in the year 2007 Greenland ice sheet melting was higher than ever, 592 km3 (142.0 cu mi). Also snowfall was unusually low, which led to unprecedented negative −65 km3 (−15.6 cu mi) Surface Mass Balance.[52] If iceberg calving has happened as an average, Greenland lost 294 Gt of its mass during 2007 (one km3 of ice weighs about 0.9 Gt).

The IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (2007) noted, it is hard to measure the mass balance precisely, but most results indicate accelerating mass loss from Greenland during the 1990s up to 2005. Assessment of the data and techniques suggests a mass balance for the Greenland Ice Sheet ranging between growth of 25 Gt/yr and loss of 60 Gt/yr for 1961 to 2003, loss of 50 to 100 Gt/yr for 1993 to 2003 and loss at even higher rates between 2003 and 2005.[53]

Analysis of gravity data from GRACE satellites indicates that the Greenland ice sheet lost approximately 2900 Gt (0.1% of its total mass) between March 2002 and September 2012. The mean mass loss rate for 2008–2012 was 367 Gt/year.[54]

A study published in 2020 estimated, by combining 26 individual estimates of mass balance derived by tracking changes in Greenland's ice sheet volume, speed and gravity as part of the Ice Sheet Mass Balance Inter-comparison Exercise, that the Greenland Ice Sheet had lost a total of 3,902 gigatons (Gt) of ice between 1992 and 2018 . The rate of ice loss has increased over time from 26 ± 27 Gt/year between 1992 and 1997 to 244 ± 28 Gt/year between 2012 and 2017 with a peak mass loss rate of 275 ± 28 Gt/year during the period 2007 and 2012.[55]

A paper on Greenland's temperature record shows that the warmest year on record was 1941 while the warmest decades were the 1930s and 1940s. The data used was from stations on the south and west coasts, most of which did not operate continuously the entire study period.[56]

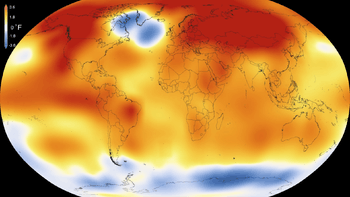

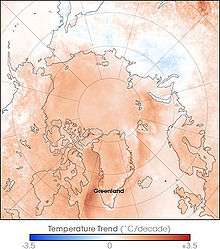

While Arctic temperatures have generally increased, there is some discussion concerning the temperatures over Greenland. First of all, Arctic temperatures are highly variable, making it difficult to discern clear trends at a local level. Also, until recently, an area in the North Atlantic including southern Greenland was one of the only areas in the World showing cooling rather than warming in recent decades,[57] but this cooling has now been replaced by strong warming in the period 1979–2005.[58]

See also

Notes

- The timing of the uplift of Greenland is known from the study of planation surfaces formed near sea-level. Greenland has two large planation surfaces: the older Upper Planation Surface and the younger Lower Planation Surface. The Upper Planation Surface has been uplifted 2000 to 3000 masl. since formation and the Lower Planation Surface has been uplifted 500 to 1000 masl.[4]

References

- Encyclopædia Britannica. 1999 Multimedia edition.

- Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) [Houghton, J.T., Y. Ding, D.J. Griggs, M. Noguer, P.J. van der Linden, X. Dai, K. Maskell, and C.A. Johnson (eds.)]Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 881pp. , "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-02-10. Retrieved 2006-02-10.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link), and .

- Thiede, JC Jessen, P Knutz, A Kuijpers, N Mikkelsen, N Norgaard-Pedersen, and R Spielhagen (2011) Millions of Years of Greenland Ice Sheet History Recorded in Ocean Sediments. Polarforschung. 80(3):141–159.

- Solgaard, Anne M.; Bonow, Johan M.; Langen, Peter L.; Japsen, Peter; Hvidberg, Christine (2013). "Mountain building and the initiation of the Greenland Ice Sheet". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 392: 161–176. Bibcode:2013PPP...392..161S. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2013.09.019.

- Yau, Audrey M.; Bender, Michael L.; Blunier, Thomas; Jouzel, Jean (2016). "Setting a chronology for the basal ice at Dye-3 and GRIP: Implications for the long-term stability of the Greenland Ice Sheet". Earth and Planetary Science Letters. 451: 1–9. Bibcode:2016E&PSL.451....1Y. doi:10.1016/j.epsl.2016.06.053.

- "The Secrets in Greenland's Ice Sheet". The New York Times. 2015.

- Impacts of a Warming Arctic: Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, Cambridge University Press, 2004. Archived 2006-11-19 at the Wayback Machine

- "Glacial Earthquakes Point to Rising Temperatures in Greenland – Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory News". columbia.edu.

- ScienceDaily, 10 October 2008: "An Accurate Picture Of Ice Loss In Greenland"

- "BBC NEWS – Science/Nature – Greenland melt 'speeding up'". bbc.co.uk. 2006-08-11.

- Small Glaciers Account for Most of Greenland's Recent Ice Loss Newswise, Retrieved on September 15, 2008.

- "Greenland ice loss is at 'worse-case scenario' levels, study finds". UCI News. 2019-12-19. Retrieved 2020-01-04.

- Irvalı, Nil; Galaasen, Eirik V.; Ninnemann, Ulysses S.; Rosenthal, Yair; Born, Andreas; Kleiven, Helga (Kikki) F. (2019-12-18). "A low climate threshold for south Greenland Ice Sheet demise during the Late Pleistocene". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 117: 190–195. doi:10.1073/pnas.1911902116. ISSN 0027-8424. PMC 6955352. PMID 31871153.

- Hansen, James; Sato, Makiko; Kharecha, Pushker; Russell, Gary; Lea, David W.; Siddall, Mark (2007). "Climate change and trace gases". Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 365 (1856): 1925–1954. Bibcode:2007RSPTA.365.1925H. doi:10.1098/rsta.2007.2052. PMID 17513270.

- "Greenland enters melt mode". Science News. 2013-09-23.

- Wall, Tim (2017-05-10). "Greenland Hits 97 Percent Meltdown in July". Discovery News.

- "NASA Made Up 150 Year Melt Cycle". Daily Kos.

- Meese, D. A.; Gow, A. J.; Grootes, P.; Stuiver, M.; Mayewski, P. A.; Zielinski, G. A.; Ram, M.; Taylor, K. C.; Waddington, E. D. (1994). "The Accumulation Record from the GISP2 Core as an Indicator of Climate Change Throughout the Holocene". Science. 266 (5191): 1680–1682. Bibcode:1994Sci...266.1680M. doi:10.1126/science.266.5191.1680. PMID 17775628.

- Sea level fears as Greenland darkens BBC

- Statham, Peter J.; Skidmore, Mark; Tranter, Martyn (2008-09-01). "Inputs of glacially derived dissolved and colloidal iron to the coastal ocean and implications for primary productivity". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 22 (3): GB3013. Bibcode:2008GBioC..22.3013S. doi:10.1029/2007GB003106. ISSN 1944-9224.

- "Glaciers Contribute Significant Iron to North Atlantic Ocean" (news release). Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution. March 10, 2013. Retrieved March 18, 2013.

- Hopwood, Mark James; Connelly, Douglas Patrick; Arendt, Kristine Engel; Juul-Pedersen, Thomas; Stinchcombe, Mark; Meire, Lorenz; Esposito, Mario; Krishna, Ram (2016-01-01). "Seasonal changes in Fe along a glaciated Greenlandic fjord". Frontiers in Earth Science. 4: 15. Bibcode:2016FrEaS...4...15H. doi:10.3389/feart.2016.00015.

- Martin, John H.; Fitzwater, Steve E.; Gordon, R. Michael (1990-03-01). "Iron deficiency limits phytoplankton growth in Antarctic waters". Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 4 (1): 5–12. Bibcode:1990GBioC...4....5M. doi:10.1029/GB004i001p00005. ISSN 1944-9224.

- Nielsdóttir, Maria C.; Moore, Christopher Mark; Sanders, Richard; Hinz, Daria J.; Achterberg, Eric P. (2009-09-01). "Iron limitation of the postbloom phytoplankton communities in the Iceland Basin" (PDF). Global Biogeochemical Cycles. 23 (3): GB3001. Bibcode:2009GBioC..23.3001N. doi:10.1029/2008GB003410. ISSN 1944-9224.

- Arendt, Kristine Engel; Nielsen, Torkel Gissel; Rysgaard, Sren; Tnnesson, Kajsa (2010-02-22). "Differences in plankton community structure along the Godthåbsfjord, from the Greenland Ice Sheet to offshore waters". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 401: 49–62. Bibcode:2010MEPS..401...49E. doi:10.3354/meps08368.

- Brown, Dwayne; Cabbage, Michael; McCarthy, Leslie; Norton, Karen (20 January 2016). "NASA, NOAA Analyses Reveal Record-Shattering Global Warm Temperatures in 2015". NASA. Retrieved 21 January 2016.

- NEEM community members; Dahl-Jensen, D.; Albert, M. R.; Aldahan, A.; Azuma, N.; Balslev-Clausen, D.; Baumgartner, M.; Berggren, A. -M.; Bigler, M.; Binder, T.; Blunier, T.; Bourgeois, J. C.; Brook, E. J.; Buchardt, S. L.; Buizert, C.; Capron, E.; Chappellaz, J.; Chung, J.; Clausen, H. B.; Cvijanovic, I.; Davies, S. M.; Ditlevsen, P.; Eicher, O.; Fischer, H.; Fisher, D. A.; Fleet, L. G.; Gfeller, G.; Gkinis, V.; Gogineni, S.; et al. (January 24, 2013). "Eemian interglacial reconstructed from a Greenland folded ice core" (PDF). Nature. 493 (7433): 489–494. Bibcode:2013Natur.493..489N. doi:10.1038/nature11789. PMID 23344358.

- Bennartz, R.; Shupe, M. D.; Turner, D. D.; Walden, V. P.; Steffen, K.; Cox, C. J.; Kulie, M. S.; Miller, N. B.; Pettersen, C. (2013). "July 2012 Greenland melt extent enhanced by low-level liquid clouds". Nature. 496 (7443): 83–86. Bibcode:2013Natur.496...83B. doi:10.1038/nature12002. PMID 23552947.

- Van Tricht, K.; Lhermitte, S.; Lenaerts, J. T. M.; Gorodetskaya, I. V.; L’Ecuyer, T. S.; Noël, B.; van den Broeke, M. R.; Turner, D. D.; van Lipzig, N. P. M. (2016-01-12). "Clouds enhance Greenland ice sheet meltwater runoff". Nature Communications. 7: 10266. Bibcode:2016NatCo...710266V. doi:10.1038/ncomms10266. PMC 4729937. PMID 26756470.

- Stefan Rahmstorf, Jason E. Box, Georg Feulner, Michael E. Mann, Alexander Robinson, Scott Rutherford & Erik J. Schaffernicht (May 2015). "Exceptional twentieth-century slowdown in Atlantic Ocean overturning circulation" (PDF). Nature. 5 (5): 475–480. Bibcode:2015NatCC...5..475R. doi:10.1038/nclimate2554.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Melting Greenland ice sheet may affect global ocean circulation, future climate". Phys.org. 2016.

- "A Top-Secret US Military Base Will Melt Out of the Greenland Ice Sheet". VICE Magazine. 9 March 2019.

- Laskow, Sarah (2018-02-27). "America's Secret Ice Base Won't Stay Frozen Forever". Wired. ISSN 1059-1028.

- Hopwood, M. J.; Carroll, D.; Browning, T. J.; Meire, L.; Mortensen, J.; Krisch, S.; Achterberg, E. P. (14 August 2018). "Non-linear response of summertime marine productivity to increased meltwater discharge around Greenland". Nature Communications. 9 (1): 3256. Bibcode:2018NatCo...9.3256H. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-05488-8. PMC 6092443. PMID 30108210.

- "Images Show Breakup of Two of Greenland's Largest Glaciers, Predict Disintegration in Near Future". NASA Earth Observatory. August 20, 2008. Retrieved 2008-08-31.

- "Huge ice island breaks from Greenland glacier". BBC News. 2010-08-07.

- Iceberg breaks off from Greenland's Petermann Glacier 19 July 2012

- "Surface Melt-Induced Acceleration of Greenland Ice-Sheet Flow by Zwally et al., "

- "Fracture Propagation to the Base of the Greenland Ice Sheet During Supraglacial Lake Drainage by Das. et al.,"

- "Thomas R.H (2004), Force-perturbation analysis of recent thinning and acceleration of Jakobshavn Isbrae, Greenland, Journal of Glaciology 50 (168): 57–66. "

- Thomas, R. H. Abdalati W; Frederick, E; Krabill, WB; Manizade, S; Steffen, K (2003). "Investigation of surface melting and dynamic thinning on Jakobshavn Isbrae, Greenland". Journal of Glaciology. 49 (165): 231–239. Bibcode:2003JGlac..49..231T. doi:10.3189/172756503781830764.

- Joughin, I; Abdalati, W; Fahnestock, M (December 2004). "Large fluctuations in speed on Greenlands Jakobshavn Isbræ glacier". Nature. 432 (7017): 608–610. Bibcode:2004Natur.432..608J. doi:10.1038/nature03130. PMID 15577906.

- "Rates of southeast Greenland ice volume loss...by Howat et al". AGU.

- "Greenland Ice Sheet: is land-terminating ice thinning at anomalously high rates by Sole et al.,"

- "Rapid and synchronous ice-dynamic changes in East Greenland by Luckman, Murray. de Lange and Hanna" "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-24. Retrieved 2008-09-27.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "Greenland Ice Sheet: is land-terminating ice thinning at anomalously high rates by Sole et al.,"

- "Moulins calving fronts and Greenland outletglacier acceleration by Pelto"

- "Modelling Precipitation over ice sheets: an assessment using Greenland", Gerard H. Roe, University of Washington,

- Wikipedia,

- airspacemag.com. "Glacier Girl: The Back Story". Air & Space Magazine. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 21 June 2020.

- "Greenland Ice Loss Doubles in Past Decade, Raising Sea Level Faster". Jet Propulsion Laboratory News release, Thursday, 16 February 2006. "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2006-10-03. Retrieved 2006-02-22.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- http://www.cosis.net/abstracts/EGU2008/03388/EGU2008-A-03388-3.pdf?PHPSESSID=

- Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M. Tignor and H.L. Miller (eds.)]. Chapter 4 Observations: Changes in Snow, Ice and Frozen Ground.IPCC, 2007. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, 996 pp.

- "Arctic Report Card: Update for 2012; Greenland Ice Sheet".

- Shepherd, Andrew; Ivins, Erik; Rignot, Eric; Smith, Ben; van den Broeke, Michiel; Velicogna, Isabella; Whitehouse, Pippa; Briggs, Kate; Joughin, Ian; Krinner, Gerhard; Nowicki, Sophie (2020-03-12). "Mass balance of the Greenland Ice Sheet from 1992 to 2018". Nature. 579 (7798): 233–239. doi:10.1038/s41586-019-1855-2. ISSN 1476-4687. PMID 31822019. Archived from the original on 27 March 2020. Alt URL

- Vinther, B. M.; Andersen, K. K.; Jones, P. D.; Briffa, K. R.; Cappelen, J. (2006). "Extending Greenland temperature records into the late eighteenth century" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research. 111 (D11): D11105. Bibcode:2006JGRD..11111105V. doi:10.1029/2005JD006810.

- see Arctic Climate Impact Assessment (2004) and IPCC Second Assessment Report, among others.

- IPCC, 2007. Trenberth, K.E., P.D. Jones, P. Ambenje, R. Bojariu, D. Easterling, A. Klein Tank, D. Parker, F. Rahimzadeh, J.A. Renwick, M. Rusticucci, B. Soden and P. Zhai, 2007: Observations: Surface and Atmospheric Climate Change. In: Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Solomon, S., D. Qin, M. Manning, Z. Chen, M. Marquis, K.B. Averyt, M. Tignor and H.L. Miller (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA.

External links

![]()

- Real Climate the Greenland Ice

- Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland (GEUS) GEUS has much scientific material on Greenland.

- Emporia State University – James S. Aber Lecture 2: Modern Glaciers and Ice Sheets.

- Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

- GRACE ice mass measurement: "Recent Land Ice Mass Flux from SpaceborneGravimetry"

- Greenland ice cap melting faster than ever, Bristol University

- Greenland Ice Mass Loss: Jan. 2004 – June 2014 (NASA animation)

- Greenland Ice Cap, 1942-1944 Report at Dartmouth College Library

- Greenland Ice Cap literary Survey/Bibliography 1953 at Dartmouth College Library