Dorset culture

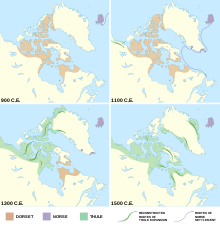

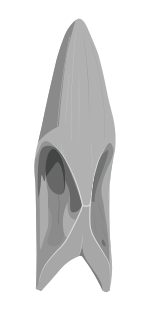

The Dorset was a Paleo-Eskimo culture, lasting from 500 BCE to between 1000 and 1500CE, that followed the Pre-Dorset and preceded the Inuit in the Arctic of North America. It is named after Cape Dorset in Nunavut, Canada, where the first evidence of its existence was found. The culture has been defined as having four phases due to the distinct differences in the technologies relating to hunting and tool making. Artifacts include distinctive triangular end-blades, soapstone lamps, and burins.

_(3034045389).jpg)

_(3034882558).jpg)

.svg.png)

The Dorset were first identified as a separate culture in 1925. The Dorset appear to have been extinct by 1500 at the latest and perhaps as early as 1000. The Thule people, who began migrating east from Alaska in the 11th century, ended up spreading through the lands previously inhabited by the Dorset. There is no strong evidence that the Inuit and Dorset ever met. Modern genetic studies show the Dorset population were distinct from later groups and that "[t]here was virtually no evidence of genetic or cultural interaction between the Dorset and the Thule peoples."[1]

Inuit legends recount them encountering people they called the Tuniit (singular Tuniq) or Sivullirmiut "First Inhabitants". According to legend, the first Inhabitants were giants, taller and stronger than the Inuit but afraid to interact and "easily put to flight."[2] There is also a controversial theory of contact and trade between the Dorset and the Norse promoted by Patricia Sutherland.[3][4][5][6]

Discovery

In 1925 anthropologist Diamond Jenness received some odd artifacts from Cape Dorset. As they were quite different from those of the Inuit, he speculated that they were indicative of an ancient, preceding culture. Jenness named the culture "Dorset" after the location of the find. These artifacts showed a consistent and distinct cultural pattern that included sophisticated art distinct from that of the Inuit. For example, the carvings featured uniquely large hairstyles for women, and figures of both sexes wearing hoodless parkas with large, tall collars. Much research since then has revealed many details of the Dorset people and their culture.

History

Origins

The origins of the Dorset people are not well understood. They may have developed from the previous cultures of Pre-Dorset, Saqqaq or (less likely) Independence I. There are, however, problems with this theory: these earlier cultures had bow and arrow technology which the Dorsets lacked. Possibly, due to a shift from terrestrial to aquatic hunting, the bow and arrow became lost to the Dorset. Another piece of technology that is missing from the Dorset are drills: there are no drill holes in Dorset artifacts. Instead, the Dorset gouged lenticular holes. For example, bone needles are common in Dorset sites, but they have long and narrow holes that have been painstakingly carved or gouged. Both the Pre-Dorset and Thule (Inuit) had drills.

Historical and cultural periods

Dorset culture and history is divided into periods: the Early (500–1 BCE), Middle (CE 1–500), and Late phases (500–1000), as well as perhaps a Terminal phase (from c. 1000 onwards). The Terminal phase, if it existed, would likely be closely related to the onset of the Medieval Warm Period, which started to warm the Arctic considerably around the mid-10th century. With the warmer climates, the sea ice became less predictable and was isolated from the High Arctic.

The Dorset were highly adapted to living in a very cold climate, and much of their food is thought to have been from hunting sea mammals that breathe through holes in the ice. The massive decline in sea-ice which the Medieval Warm Period produced would have strongly affected the Dorset. They could have followed the ice north. Most of the evidence suggests that they disappeared some time between 1000 and 1500. Scientists have suggested that they disappeared because they were unable to adapt to climate change[7] or that they were vulnerable to newly introduced disease.[8]

Technology

The Dorset adaptation was different from that of the whaling-based Thule Inuit. Unlike the Inuit, they rarely hunted land animals, such as polar bears and caribou. They did not use bows or arrows. Instead, they seem to have relied on seals and other sea mammals that they apparently hunted from holes in the ice. Their clothing must have been adapted to the extreme conditions.

Triangular end-blades and burins are diagnostic of the Dorset. The end-blades were hafted onto harpoon heads. They primarily used the harpoons to hunt seal, but also hunted larger sea mammals such as walrus and narwhals. They made kudlik lamps from soapstone and filled them with seal oil. Burins were a type of stone flake with a chisel-like edge. They were probably either used for engraving or for carving wood or bone. The burins were also used by Pre-Dorset groups and had distinctive mitten shape.

The Dorset were highly skilled at making refined miniature carvings, and striking masks. Both indicate an active shamanistic tradition. The Dorset culture was remarkably homogeneous across the Canadian Arctic, but there were some important variations which have been noted in both Greenland and Newfoundland/Labrador regions.

Interaction with the Inuit

There appears to be no genetic connection between the Dorset and the Thule who replaced them.[9] Archaeological and legendary evidence is often thought to support some cultural contact, but this has been questioned.[10] The Dorset people, for instance, engaged in seal-hole hunting, a method which requires several steps and includes the use of dogs. The Thule apparently did not use this technique in the time they had previously spent in Alaska. Settlement pattern data has been used to claim that the Dorset also extensively used a breathing-hole sealing technique and perhaps they would have taught this to the Inuit. But this has been questioned on the grounds that there is no evidence that the Dorset had dogs.[10]

Some elders describe peace with an ancient group of people, while others describe conflict.[11]

The Sadlermiut

The Sadlermiut were a people living in near isolation mainly on and around Coats Island, Walrus Island, and Southampton Island in Hudson Bay up until 1902–03. Encounters with Europeans and exposure to infectious disease caused the deaths of the last members of the Sadlermiut.

Scholars had believed the Sadlermiut were the last remnants of the Dorset culture, as they had a culture and dialect distinct from the mainland Inuit. Supporting this a 2002 mitochondrial DNA research showed that the Sadlermiut bore a mitochrondrial relationship to both the Dorset and Thule peoples, perhaps suggesting local admixture.[12]

However a subsequent 2012 genetic analysis showed no genetic link between the Sadlermiut and the Dorset.[13]

See also

Bibliography

- Michael Fortescue, Steven Jacobson & Lawrence Kaplan (1994): Comparative Eskimo Dictionary; with Aleut Cognates (Alaska Native Language Center Research Paper 9); ISBN 1-55500-051-7

- Robert McGhee (2005): The Last Imaginary Place: A Human History of the Arctic World; ISBN 0-19-518368-1

- Robert McGhee (2001): Ancient People of the Arctic

- Plummet Patrick, Lebel Serge (1997). "Dorset Tip Fluting: A Second 'American' Invention". Arctic Anthropology. 34 (2): 132–162.

- Renouf M.A.P. (1999). "Prehistory of Newfoundland Hunter-Gatherers: Extinctions or Adaptations?". World Archaeology. 30 (3): 403–420. doi:10.1080/00438243.1999.9980420.

References

- "Dorset DNA: Genes Trace the Tale of the Arctic's Long-Gone 'Hobbits' - NBC News". NBC News.

- "When science meets aboriginal oral history". Toronto Star.

- Weber, Bob (22 July 2018). "Ancient Arctic people may have known how to spin yarn long before Vikings arrived". Old theories being questioned in light of carbon-dated yarn samples. CBC. Retrieved 2 January 2019.

… Michele Hayeur Smith of Brown University in Rhode Island, lead author of a recent paper in the Journal of Archaeological Science. Hayeur Smith and her colleagues were looking at scraps of yarn, perhaps used to hang amulets or decorate clothing, from ancient sites on Baffin Island and the Ungava Peninsula. The idea that you would have to learn to spin something from another culture was a bit ludicrous," she said. "It's a pretty intuitive thing to do.

- Barber, Elizabeth Wayland (1992) Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean, Princeton University Press, "We now have at least two pieces of evidence that this important principle of twisting for strength dates to the Palaeolithic. In 1953, the Abbé Glory was investigating floor deposits in a steep corridor of the famed Lascaux caves in southern France […] a long piece of Palaeolithic cord […] neatly twisted in the S direction […] from three Z-plied strands […]" ISBN 0-691-00224-X

- Smith, Michèle Hayeur; Smith, Kevin P.; Nilsen, Gørill (August 2018). "Journal of Archaeological Science". Dorset, Norse, or Thule? Technological Transfers, Marine Mammal Contamination, and AMS Dating of Spun Yarn and Textiles from the Eastern Canadian Arctic. Elsevier. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2018.06.005. S2CID 52035803.

However, the date received on Sample 4440b from Nanook clearly indicates that sinew was being spun and plied at least as early, if not earlier, than yarn at this site. We feel that the most parsimonious explanation of this data is that the practice of spinning hair and wool into plied yarn most likely developed naturally within this context of complex, indigenous, Arctic fiber technologies, and not through contact with European textile producers. [. . .] Our investigations indicate that Paleoeskimo (Dorset) communities on Baffin Island spun threads from the hair and also from the sinews of native terrestrial grazing animals, most likely musk ox and arctic hare, throughout the Middle Dorset period and for at least a millennium before there is any reasonable evidence of European activity in the islands of the North Atlantic or in the North American Arctic

- Armstrong, Jane (20 November 2012). "Vikings in Canada?". A researcher says she’s found evidence that Norse sailors may have settled in Canada’s Arctic. Others aren’t so sure. Maclean's. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

In fact, Fitzhugh thinks the cord at the centre of Sutherland’s “eureka” moment is a Dorset artifact. “We have very good evidence that this kind of spun cordage was being used hundreds of years before the Norse arrived in the New World, in other words 500 to 600 CE, at the least,” he says.

- "New Study Offers Clues to Swift Arctic Extinction". New York Times.

- "The strange history of the North American Arctic". Science AAAS.

- Maanasa Raghavan; Eske Willerslev; et al. (August 29, 2014). "The genetic prehistory of the New World Arctic". Science. 345 (6200): 1020. doi:10.1126/science.1255832. PMID 25170159.

- Robert W. Park (1993). "The Dorset-Thule succession in Arctic North America: Assessing claims for culture contact". American Antiquity. 58 (2): 203–234. doi:10.2307/281966. JSTOR 281966.

- "Inuit stories of the Tuniit backed up by science". Northern News Services. Archived from the original on 2017-08-03. Retrieved 2017-07-27.

- "Arctic Studies Center Newsletter page 34" (PDF). National Museum of Natural History. Smithsonian Institution. June 2002. Retrieved 2008-10-13.

- Robert W. Park (August 29, 2014). "Stories of Arctic colonization". Science. 345 (6200): 1004–05. doi:10.1126/science.1258607. PMID 25170138. Retrieved 2015-08-08.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dorset culture. |

- "Dorset Culture in Nunavik", Avataq

- "In the bones of the world", Nuntsiaq News

- "Sadlermiut", Canadian Encyclopedia

- "Dorset Paleoeskimo Culture", Canada.ca.