Germanwings Flight 9525

Germanwings Flight 9525[1][lower-alpha 1] was a scheduled international passenger flight from Barcelona–El Prat Airport in Spain to Düsseldorf Airport in Germany. The flight was operated by Germanwings, a low-cost carrier owned by the German airline Lufthansa. On 24 March 2015, the aircraft, an Airbus A320-211, crashed 100 km (62 mi; 54 nmi) north-west of Nice in the French Alps. All 144 passengers and six crew members were killed.[2][3] It was Germanwings' first fatal crash in the 18-year history of the company.

.jpg) D-AIPX, the aircraft involved, in May 2014 | |

| Incident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 24 March 2015 |

| Summary | Suicide by pilot |

| Site | Prads-Haute-Bléone, Alpes-de-Haute-Provence, France 44°16′50″N 6°26′20″E |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Airbus A320-211 |

| Operator | Germanwings |

| IATA flight No. | 4U9525 |

| ICAO flight No. | GWI18G[1] |

| Call sign | GERMANWINGS 18 GOLF |

| Registration | D-AIPX |

| Flight origin | Barcelona–El Prat Airport, Barcelona, Spain |

| Destination | Düsseldorf Airport, Düsseldorf, Germany |

| Occupants | 150 |

| Passengers | 144 |

| Crew | 6 |

| Fatalities | 150 |

| Survivors | 0 |

The investigation determined that the crash was caused deliberately by the co-pilot, Andreas Lubitz, who had previously been treated for suicidal tendencies and declared "unfit to work" by his doctor. Lubitz kept this information from his employer and instead reported for duty. Shortly after reaching cruise altitude and while the captain was out of the cockpit, he locked the cockpit door and initiated a controlled descent that continued until the aircraft impacted a mountainside.

In response to the incident and the circumstances of the co-pilot's involvement, aviation authorities in some countries implemented new regulations that require the presence of two authorized personnel in the cockpit at all times.[4][5][6][7] Three days after the incident, the European Aviation Safety Agency issued a temporary recommendation for airlines to ensure that at least two crew members—including at least one pilot—were in the cockpit for the entire duration of the flight.[8] Several airlines announced that they had already adopted similar policies voluntarily.[9][10][11]

Flight

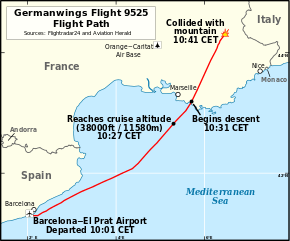

Germanwings Flight 9525 took off from Runway 07R at Barcelona–El Prat Airport on 24 March 2015 at 10:01 am CET (09:01 UTC) and was due to arrive at Düsseldorf Airport by 11:39 CET.[2][12] The flight's scheduled departure time was 9:35 CET.[13] According to the French national civil aviation inquiries bureau, the Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety (BEA),[14] the pilots confirmed instructions from French air traffic control at 10:30 CET. At 10:31 CET, after crossing the French coast near Toulon, the aircraft left its assigned cruising altitude of 38,000 ft (11,600 m) and without approval began to descend rapidly. The air traffic controller declared the aircraft in distress after its descent and loss of radio contact.[15][16][17]

The descent time from 38,000 ft was about 10 minutes; radar observed an average descent rate around 3,400 ft/min (58 ft/s (18 m/s)).[18] Attempts by French air traffic control to contact the flight on the assigned radio frequency were not answered. A French military Mirage jet was scrambled from the Orange-Caritat Air Base to intercept the aircraft.[19][20] According to the BEA, radar contact was lost at 10:40 CET; at the time, the aircraft had descended to 6,175 feet (1,880 m),[21] and crashed in the remote commune of Prads-Haute-Bléone, 100 km (62 mi; 54 nmi) north-west of Nice.[22][23][24][25] A seismological station of the Sismalp network, the Grenoble Observatory, 12 km (7.5 mi; 6.5 nmi) from the crash site, recorded the associated seismic event, determining the crash time as 10:41:05 CET.[26]

The crash is the deadliest air disaster in France since the 1981 crash of Inex-Adria Aviopromet Flight 1308, in which 180 people died, and the third-deadliest French air disaster of all time, behind Flight 1308 and Turkish Airlines Flight 981.[27] This was the first major crash of a civil airliner in France since the crash of Air France Flight 4590 on takeoff from Charles de Gaulle Airport in 2000.[28][29]

Crash site

The crash site is within the Massif des Trois-Évêchés, 3 km (1.9 mi; 1.6 nmi) east of the settlement Le Vernet and beyond the road to the Col de Mariaud, in an area known as the Ravin du Rosé.[30] The aircraft crashed on the southern side of the Tête du Travers,[31] a minor peak in the lower western slopes of the Tête de l'Estrop. The site is about 10 km (6 mi; 5 nmi) west of Mount Cimet, where Air France Flight 178 crashed in 1953.[32][33]

Gendarmerie nationale and Sécurité Civile sent helicopters to locate the wreckage.[34] The aircraft had disintegrated; the largest piece of wreckage was "the size of a car."[35] A helicopter landed near the crash site; its personnel confirmed no survivors.[36] The search and rescue team reported the debris field covered 2 km2 (500 acres).[24]

Aircraft

The aircraft involved was a 24-year-old Airbus A320-211,[lower-alpha 2] serial number 147, registered as D-AIPX. It made its first flight on 29 November 1990[37] and was delivered to Lufthansa on 5 February 1991.[38][39] The aircraft was leased to Germanwings from 1 June 2003 until mid-2004,[40] then returned to Lufthansa on 22 July 2004 and remained with the airline until it was transferred to Germanwings again on 31 January 2014.[39][40] The aircraft had accumulated about 58,300 flight hours on 46,700 flights.[41]

Crew and passengers

| Citizenship | No. | Ref. |

|---|---|---|

| Germany[lower-alpha 3] | 72 | [43] |

| Spain | 51 | [44] |

| Argentina | 3 | [45] |

| Kazakhstan | 3 | [46] |

| United Kingdom[lower-alpha 4] | 3 | [49] |

| United States | 3 | [50] |

| Australia | 2 | [51] |

| Colombia | 2 | [52] |

| Iran | 2 | [53] |

| Japan | 2 | [54] |

| Mexico[lower-alpha 5] | 2 | [56] |

| Morocco | 2 | [57] |

| Venezuela | 2 | [58] |

| Belgium | 1 | [59] |

| Chile | 1 | [60] |

| Denmark | 1 | [61] |

| Israel | 1 | [62] |

| Netherlands | 1 | [63] |

| Some passengers had multiple citizenship. Counts are based on preliminary data and do not total 150. | ||

During its final flight, the aircraft was carrying 144 passengers and six crew (two pilots and four cabin crew members)[2][64] from at least 18 countries—mostly Germany and Spain.[16] The count was confused by the multiple citizenship status of some people on board.[65]

Crew

The flight's pilot in command was 34-year-old Captain Patrick Sondenheimer,[66] who had 10 years of flying experience (6,000 flight hours, including 3,811 hours on the Airbus A320)[22] flying A320s for Germanwings, Lufthansa, and Condor.[67][17] The co-pilot was 27-year-old Andreas Lubitz,[68] who joined Germanwings in September 2013 and had 630 flight hours of experience, with 540 of them on the Airbus A320.[69][70]

Andreas Lubitz

Andreas Günter Lubitz[71] was born on 18 December 1987 and grew up in Neuburg an der Donau, Bavaria[72] and Montabaur in the German state of Rhineland-Palatinate.[67] He took flying lessons at Luftsportclub Westerwald, an aviation sports club in Montabaur.[67][73]

Lubitz was accepted into a Lufthansa trainee programme after finishing high school. In September 2008, he began training at the Lufthansa Flight Training school in Bremen, Germany.[1][67] He suspended his pilot training in November 2008 after being hospitalized for a severe episode of depression. After his psychiatrist determined that the depressive episode was fully resolved, Lubitz returned to the Lufthansa school in August 2009.[1][74][75][76][77] Lubitz moved to the United States in November 2010 to continue training at the Lufthansa Airline Training Center in Goodyear, Arizona.[78][79] From June 2011 to December 2013, he worked as a flight attendant for Lufthansa while training to obtain his commercial pilot's licence,[67][73] until joining Germanwings as a first officer in June 2014.[1]

Passengers

Among the passengers were 16 students and two teachers from the Joseph-König-Gymnasium of Haltern am See, North Rhine-Westphalia. They were returning home from a student exchange with the Giola Institute in Llinars del Vallès, Barcelona.[80] Haltern's mayor, Bodo Klimpel, described the crash as "the darkest day in the history of [the] town".[81] Bass-baritone Oleg Bryjak and contralto Maria Radner, singers with Deutsche Oper am Rhein, were also on the flight.[82][83]

Investigation

The French BEA opened an investigation into the crash; it was joined by its German counterpart, the Federal Bureau of Aircraft Accident Investigation. The BEA was assisted by the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation.[84][85] Hours after the crash, the BEA sent seven investigators to the crash site; these were accompanied by representatives from Airbus and CFM International. The cockpit voice recorder, which was damaged but still usable, was recovered by rescue workers and was examined by the investigation team.[86][87][88][89][90] The following week, Brice Robin, the government prosecutor based in Marseille, announced that the flight data recorder, which was blackened by fire but still usable, had also been found.[91][92] Investigators isolated 150 sets of DNA, which were compared with the DNA of the victims' families.[93][94]

Cause of crash

According to French and German prosecutors, the crash was deliberately caused by the co-pilot, Andreas Lubitz.[29][95][96] Brice Robin said Lubitz was initially courteous to Captain Sondenheimer during the first part of the flight, then became "curt" when the captain began the midflight briefing on the planned landing.[97] Robin said when the captain returned from probably using the toilet and tried to enter the cockpit, Lubitz had locked the door.[29][95] The captain had a code to unlock the door, but the lock's code panel can be disabled from the cockpit controls.[5][98] The captain requested re-entry using the intercom; he knocked and then banged on the door, but received no response.[99] The captain then tried to break down the door, but like most cockpit doors made after the September 11 attacks, it had been reinforced to prevent intrusion. The captain asked cabin crew to bring a crash axe to try and ply the door open to try to gain access to the cockpit, which can be heard being used as loud bangs on the CVR recovered from the crash site.[100][14][75][101] During the descent, the co-pilot did not respond to questions from air traffic control, nor transmit a distress call.[102] Robin said contact from the Marseille air traffic control tower, the captain's attempts to break in, and Lubitz's steady breathing were audible on the cockpit voice recording.[95][103] The screams of passengers in the last moments before impact were also heard on the recording.[97]

After their initial analysis of the aircraft's flight data recorder, the BEA concluded that Lubitz had made flight control inputs that led to the accident, though it had yet to be determined why. He had set the autopilot to descend to 100 ft (30 m) and accelerated the speed of the descending aircraft several times thereafter.[104][105] The aircraft was travelling at 700 km/h (380 kn; 435 mph) when it crashed into the mountain.[97] The BEA preliminary report into the crash was published on 6 May 2015, six weeks later. It confirmed the initial analysis of the aircraft's flight data recorder and revealed that during the earlier outbound Flight 9524 from Düsseldorf to Barcelona, Lubitz had practised setting the autopilot altitude dial to 100 ft several times while the captain was out of the cockpit.[106][107]

The BEA final report into the crash was published on 13 March 2016. The report confirmed the findings made in the preliminary report and concluded that Lubitz had deliberately crashed the aircraft as a suicide, which stated:[1][108]

The collision with the ground was due to the deliberate and planned action of the co-pilot, who decided to commit suicide while alone in the cockpit. The process for medical certification of pilots, in particular self-reporting in case of a decrease in medical fitness between two periodic medical evaluations, did not succeed in preventing the co-pilot, who was experiencing mental disorder with psychotic symptoms, from exercising the privilege of his license.

The following factors may have contributed to the failure of this principle:

- The co-pilot’s probable fear of losing his ability to fly as a professional pilot if he had reported his decrease in medical fitness to an AME

- The potential financial consequences generated by the lack of specific insurance covering the risks of loss of income in case of unfitness to fly

- The lack of clear guidelines in German regulations on when a threat to public safety outweighs the requirements of medical confidentiality

Security requirements led to cockpit doors designed to resist forcible intrusion by unauthorized persons. This made entering the flight compartment impossible before the aircraft impacted the terrain in the French Alps.

— Causes, BEA Final Report

Investigation of Lubitz

Three days after the crash, German detectives searched Lubitz's Montabaur properties and removed a computer and other items for testing. They did not find a suicide note nor any evidence his actions had been motivated by "a political or religious background".[109][110][111] During their search of Lubitz's apartment, detectives found a letter in a waste bin indicating he had been declared unfit to work by a doctor. Germanwings stated it had not received a sick note from Lubitz for the day of the flight. News accounts said Lubitz was "hiding an illness from his employers";[112][113][114][115][116] under German law, employers do not have access to employees' medical records, and sick notes excusing a person from work do not give information about medical conditions.[117]

The following day, authorities again searched Lubitz's home, where they found evidence he was taking prescription drugs and suffered from a psychosomatic illness.[118][119] Criminal investigators said Lubitz's web searches on his tablet computer in the days leading up to the crash included "ways to commit suicide" and "cockpit doors and their security provisions".[91][92][93] Prosecutor Brice Robin said doctors had told him Lubitz should not have been flying, but medical secrecy requirements prevented this information from being made available to Germanwings.[120][121]

In the weeks before the BEA's preliminary report, the investigation into Lubitz found he had been treated for suicidal tendencies prior to his training as a commercial pilot and had been temporarily denied a US pilot's license because of these treatments for depression.[122][123][124] The final report of the BEA confirmed the preliminary report's findings, saying the co-pilot began showing symptoms of psychotic depression.[1][lower-alpha 6] For five years, Lubitz had frequently been unable to sleep because of what he believed were vision problems; he consulted over 40 doctors and feared he was going blind.[120][121][125] Motivated by the fear that blindness would cause him to lose his pilot's licence, he began conducting online research about methods of committing suicide before deciding to crash Flight 9525.[1][67][121][125][126]

Aftermath

Political

French Minister of the Interior Bernard Cazeneuve announced that due to the "violence of the impact", "little hope" existed that any survivors would be found.[127] Then-Prime Minister Manuel Valls dispatched Cazeneuve to the scene and set up a ministerial task force to coordinate the response to the incident.[128]

German Foreign Minister Frank-Walter Steinmeier flew over the crash site; he described it as "a picture of horror".[128] German Chancellor Angela Merkel and the minister-president of North Rhine-Westphalia Hannelore Kraft travelled to the crash site the following day.[129][130] Merkel, Valls, and Spanish Prime Minister Mariano Rajoy visited the recovery operations base at Seyne-les-Alpes.[131] Bodo Klimpel, mayor of Haltern am See, reacting to the deaths of 16 students and two teachers from the town, said that people were shocked by the crash.[132]

Commercial

Lufthansa chief executive officer Carsten Spohr visited the crash location the day following the crash; he said it was "the darkest day for Lufthansa in its 60-year history".[133] Several Germanwings flights were cancelled on 24 and 25 March due to the pilots' grief at the loss of their colleagues.[134] Germanwings retired the flight number 4U9525, changing it to 4U9441; the outbound flight number was changed from 4U9524 to 4U9440.[135] In the days following the crash, Lufthansa at first said it saw no reason to change its procedures, then reversed its earlier statement by introducing a new policy across its airlines requiring the presence of two crew members in the cockpit at all times.[136][137][138]

Regulatory

In response to the incident and the circumstances of Lubitz's involvement in it, aviation authorities in some countries (including Australia, Canada, Germany, and New Zealand) implemented new regulations that require two authorized personnel to be present in the cockpit of large passenger aircraft at all times.[4][5][6][7] While the United States Federal Aviation Administration,[lower-alpha 7][11][139] the Civil Aviation Administration of China[lower-alpha 8][140][141] and some European airlines already had a similar "rule of two" requirement, the European Aviation Safety Agency recommended the introduction of similar legal changes.[6][142] Other airlines announced similar changes to their policies.[4][10]

The British Psychological Society issued a statement offering to provide expert support in psychological testing and monitoring of pilots.[143] The European Federation of Psychologists' Associations issued a statement supporting psychological testing in the selection of pilots, but also stated it could not forecast the life events and mental health problems of individual pilots, nor could it predict the unique ways pilots would cope with these. It said priority should be given to psychological help for relatives and friends of victims in the aftermath of a disaster.[144] Lufthansa CEO Carsten Spohr proposed random checks of pilots' psychological fitness and a loosening of the extant physician–patient confidentiality laws. Politicians began echoing the call for a loosening of the laws in exceptional cases.[145][146]

The National Gendarmerie, a national police force in France that prides itself on toughness and resilience, introduced a new set of support mechanisms to minimize the psychosocial risks to relief workers who deal with events such as Flight 9525 in their daily jobs.[147]

Compensation

Germanwings' parent company Lufthansa offered victims' families an initial aid payment up to €50,000, separate from any legally required compensation for the disaster. Elmar Giemulla, a professor of aviation law at the Technical University of Berlin quoted by the Rheinische Post, said he expected the airline would pay €10–30 million in compensation. The Montreal Convention sets a per-victim cap of €143,000 in the event an airline is held liable, unless negligence can be proven.[148][149] Insurance specialists said although co-pilot Andreas Lubitz hid a serious illness from his employer and deliberately crashed the passenger aircraft, these facts would not affect the issue of compensation nor be applicable to the exclusion clause in Lufthansa's insurance policy.[148] Lufthansa's insurance company set aside US$300 million (€280 million) for financial compensation to victims' families and for the cost of the aircraft.[150][151]

As of February 2017, Lufthansa had paid €75,000 to every family of a victim, as well as €10,000 pain and suffering compensation to every close relative of a victim. A lawyer for the families was preparing a lawsuit in Germany to extract higher compensation.[152]

Commemorative

Shortly after the crash, a memorial stone in memory of the victims was erected near the crash site in Le Vernet.[153] The following month, about 1,400 relatives of victims, senior politicians, rescue workers, and airline employees attended a memorial service at Cologne Cathedral.[154] The parents of Andreas Lubitz were invited to the service but did not attend.[155]

The remains of 15 of the 16 school children and their two teachers arrived in their home town of Haltern for burial two months after the crash. Residents held white roses as the hearses passed the children's school, where 18 trees—one for each victim—had been planted as a memorial.[156] In Düsseldorf on the same day, the remains of 44 of the 72 German victims arrived for burial. Errors on the victims' death certificates had caused a delay. A lawyer representing the families of 34 victims said that burying the remains would help many relatives achieve closure.[157]

Second anniversary

The Lubitz family held a press conference on 24 March 2017, two years after the crash. Lubitz's father said that they did not accept the official investigative findings that Andreas Lubitz deliberately caused the crash or that he had been depressed at the time. They presented aviation journalist Tim van Beveren, whom they had commissioned to publish a new report, which asserted that Lubitz could have fallen unconscious, that the cockpit door lock had malfunctioned on previous flights, and that potentially dangerous turbulence had been reported in the area on the day of the crash. The timing of the press conference by Lubitz's father, on the anniversary of the crash, was criticized by families of the victims, who were holding their own remembrances on that day.[158][159][160][161]

Dramatisation

The crash was dramatised in season 16 of the Canadian TV series Mayday in an episode entitled "Murder in the Skies".[162] The episode aired on 24 January 2017.[163]

See also

Notes

- Abbreviated forms of the flight name combine the airline's IATA airline code (4U) or ICAO airline code (GWI) with the flight number.

- The aircraft was an Airbus A320-200 model; the infix '11' signifies it was fitted with CFM International CFM56-5A1 engines.

- Includes two passengers with dual Bosnian–German citizenship.[42]

- Includes one passenger with Spanish–Polish–British citizenship.[47][48]

- Includes one passenger with dual Mexican–Spanish citizenship.[55]

- The final investigative report of the BEA was released on 13 March 2016. The investigation concluded that the process of medical certifications for pilots, in particular, self-reporting in case of decrease in medical fitness between two periodic medical evaluations, did not succeed in preventing the co-pilot from exercising the privilege of his licence. The report also stated that the co-pilot was experiencing mental disorder with psychotic symptoms.[1]

- Rule enacted following the September 11 attacks.

- Rule enacted following the disappearance of Malaysia Airlines Flight 370.

References

- "Final Investigation Report: Accident to the Airbus A320-211, registered D-AIPX and operated by Germanwings, flight GWI18G, on 03/24/15 at Prads-Haute-Bléone". Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la Sécurité de l'Aviation Civile. 13 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016. - PDF of the English translation of the final report, and the original French version (which the BEA notes on PDF p. 2/110 of the English PDF is the primary work of reference)

- "Ce que l'on sait du crash de l'Airbus A320 entre Digne et Barcelonnette" [What is known about the crash of the Airbus A320 between Digne and Barcelonnette] (in French). BFMTV. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "No survivors from German airliner crash in French Alps". aljazeera.com. Al Jazeera. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Flight 4U9525: Canadian airlines told to have 2 people in the cockpit". CBC News. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Cooke, Henry (27 March 2015). "CAA changes cockpit policy following Germanwings crash". Fairfax New Zealand. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Crash: How the Aviation Industry Has Reacted". The Wall Street Journal. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Freed, Jamie (30 March 2015). "'Rule of two': Australia to require two in a cockpit at all times in wake of Germanwings tragedy". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- "EASA recommends minimum two crew in the cockpit". EASA. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "Germanwings crash: airlines change cockpit rules after co-pilot blamed – as it happened". The Guardian. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Germanwings investigators find torn-up sicknote in co-pilot's home". The Guardian. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Flight 4U9525 co-pilot Andreas Lubitz 'hid illness' from employer". CBC News. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Germanwings (4U) #9525 ✈ 24-Mar-2015 ✈ LEBL / BCN – EDDL / DUS". FlightAware. 24 March 2015. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "(4U) Germanwings 9525 Flight Status". Flightstats. Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Clark, Nicola; Bilefsky, Dan (26 March 2015). "Germanwings Pilot Was Locked Out of Cockpit Before Crash in France". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Germanwings flight 4U9525 crashes in French Alps with 150 on board – live updates". The Guardian. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "As it happened: Airbus A320 crash". BBC News. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Alps plane crash: What happened?". BBC News. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "What Happened on the Germanwings Flight". The New York Times. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Ce que l'on sait sur le crash de l'A320 dans les Alpes" [What is known about the crash of the A320 in the Alps]. Libération (in French). 25 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Germanwings plane crash: Airbus A320 glide to destruction 'took 18 minutes not 8'". The Independent. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "BEA Pressconference 25.05.2015 slides". BEA. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Crash: Germanwings A320 near Barcelonnette on Mar 24th 2015, lost height and impacted terrain". The Aviation Herald. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Rosnoblet, Jean Francois. "German Airbus crashes in French Alps with 150 dead, black box found". Reuters. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "German Airbus A320 plane crashes in French Alps". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Withnall, Adam (24 March 2015). "A320 crashes: Germanwings Flight down in southern France". The Independent. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Notice F. Thouvenot". isterre.fr (in French). Retrieved 20 January 2020.

- Clark, Nicola; Bilefsky, Dan (24 March 2015). "Germanwings Crash in French Alps Kills 150; Cockpit Voice Recorder Is Found". The New York Times. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "French Alps plane crash: Germanwings crew 'did not send distress signal'". The Independent. Independent Digital News and Media Ltd. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Hepher, Tim; Rosnoblet, Jean-Francois (27 March 2015). "Co-pilot suspected of deliberately crashing Germanwings jet". Reuters. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Condolencias de MeteoCampoo Accidente GWI9525" [The condolences of MeteoCampoo for the GWI9525 accident] (in Spanish). Meteo Campoo. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Airbus A320 crashes in French Alps with 150 people on board: as it happened". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Analysis: Crash of Germanwings Flight 9525 – Investigation and Latest Responses". vindobona.org. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- Gover, Dominic (24 March 2015). "Germanwings Flight 4U9525 crashed in identical spot as 1953 air disaster in French Alps near Barcelonette". International Business Times. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Plane crashes in French Alps, 150 feared dead". Grand Forks Herald. Reuters. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Crash of an A320 in south of France – more details". Airlive. Archived from the original on 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "150 killed in French Alps aircrash". Echo. Press Association. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "4U9525 Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "D-AIPX Germanwings Airbus A320-200 – cn 147". planespotters.net. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "Aircraft Registration Database Lookup". airframes.org. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "Airbus A320 – MSN 147 – D-AIPX Airline Germanwings". Airfleets.net. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- Engel, Pamela; Kelley, Michael B. (24 March 2015). "A plane with 150 people aboard crashed in France – no survivors expected". Business Insider. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Fehret i Emira iz BiH među žrtvama tragičnog leta". Avaz (in Bosnian). Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Zahl der deutschen Opfer steigt auf 72" [Number of German toll rises to 72]. n-tv (in German). 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Spain raises Spanish death toll on Germanwings flight to 51". Reuters. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Quiénes eran los argentinos fallecidos en la tragedia aérea de Germanwings en Francia" [Who were the Argentinians who died in the Germanwings tragedy in France]. Infobae (in Spanish). 24 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "На борту разбившегося во Франции самолета находились трое граждан Казахстана" [On board the aircraft crashed in France were three citizens of Kazakhstan] (in Russian). Interfax. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Katastrofa samolotu Germanwings. 150 osób na pokładzie. Nikt nie przeżył" [Germanwings plane crash. 150 people on board. Nobody survived]. gazeta.pl (in Polish). 24 March 2015. Archived from the original on 25 October 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Gordon Rayner; Josie Ensor (25 March 2015). "Germanwings crash: British victims named as Martyn Matthews, Paul Bramley and Julian Pracz-Bandres". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Alps air crash killed three Britons, says Hammond". BBC News. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Third American Killed in Germanwings Crash, State Department Says". HuffPost. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Germanwings plane crash: Two Australians among 150 victims of Airbus A320 crash, which included 16 school children". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Dos colombianos viajaban en el avión que chocó en los Alpes franceses" [Two Colombians were aboard the plane that crashed in the French Alps]. Caracol Radio (in Spanish). 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Tasnim Reporter Among Germanwings Crash Victims". Tasnim News Agency. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Two Japanese feared dead in French Alps plane crash; voice recorder found". Japan Times. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Iván Saldaña (26 March 2015). "Dora Isela Salas, la otra mexicana víctima del vuelo 9525". Excélsior (in Spanish). Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "SRE identifica a 2 mexicanas que murieron en avionazo" [SRE identifies 2 Mexicans who died in a plane crash]. Milenio (in Spanish). Mexico City. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "ثنائي مغربي ضمن ضحايا الطائرة المتحطّمة على التراب الفرنسي" [Two Moroccan victims were in the aircraft that crashed on French soil]. Hespress (in Arabic). 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Germanwings includes two Venezuelans among plane crash victims". El Universal. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Belg onder doden vliegtuigcrash" [Belgian among the dead in airplane crash]. AD (in Dutch). 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Chilena figura entre las víctimas fatales de avión accidentado en Francia" [Chilean among the dead victims of the aircraft accident in France]. EMOL (in Spanish). Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- de Stordeur, Gudmund (24 March 2015). "Dansker blandt de omkomne i flystyrt" [Dane died in plane crash]. nyhederne.tv2.dk (in Danish). Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Eichner, Itamar (24 March 2015). "Israeli among 150 killed in Germanwings crash named". Yedioth Ahronoth. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Zeker één Nederlandse dode bij crash Frankrijk" [Certainly one Dutch dead in France crash] (in Dutch). nos.nl. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "French police confirm – No survivors after plane crash – as it happened". News24. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Flight 9525 crash: 2 Americans among 150 killed". AL.com. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- Shoichet, Catherine E. (31 March 2015). "Who was Patrick Sondenheimer, the captain of Germanwings Flight 9525?". CNN. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Sawer, Patrick (29 March 2015). "Andreas Lubitz: Everything we know about Germanwings plane crash co-pilot". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Co-Pilot Named as Andreas Lubitz". The Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Co. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Germanwings crash: Who was co-pilot Andreas Lubitz?". BBC News. 23 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Kozlowska, Hanna (26 March 2015). "What we know so far about Andreas Lubitz, the co-pilot who "deliberately" crashed the Germanwings plane". Quartz. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- Kulish, Nicholas; Clark, Nicola (18 April 2015). "Germanwings Crash Exposes History of Denial on Risk of Pilot Suicide". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- "Andreas Lubitz: first picture of Germanwings co-pilot's father emerges". The Daily Telegraph. 1 April 2015.

- "Germanwings Flight 9525 co-pilot said to be "happy" with his job". CBS News. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 29 August 2015.

- "Lufthansa flight school knew of crash pilot's depression". Reuters. 31 March 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Germanwings plane crash: Reports co-pilot suffered from depression six years ago as police search homes; pilot bashed cockpit door with axe". ABC News. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Germanwings Plane Crash Investigation". The Guardian. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Lufthansa helps investigation progress". Germany: lufthansagroup.com. 31 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 18 April 2015.

- "Officials: German pilot in crash trained in Goodyear". The Arizona Republic. Phoenix. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

Ruecker said Lubitz also trained in Goodyear, Arizona.

- Ewing, Jack; Eddy, Melissa (26 March 2015). "Andreas Lubitz, Who Loved to Fly, Ended Up on a Mysterious and Deadly Course". The New York Times. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- "Germanwings A320 Crash Victims Include 15 German Schoolchildren, Local Media Reports". International Business Times. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "As Night Falls, Officials Call Off Search Operation For German Plane". wusfnews. wusf.usf.edu. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "Germanwings plane crash: two opera singers confirmed among dead". The Guardian. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Humphreys, Garry (26 March 2015). "Maria Radner: Internationally acclaimed contralto who was due to make her Bayreuth Festival debut later this year". The Independent. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "FBI assisting in crash investigation". CNN. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Flight 9525 co-pilot deliberately crashed plane, officials say". CNN. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Germanwings A320 black box found in French Alps". RT. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Germanwings plane black box found as investigators reach crash site". The Guardian. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "French Interior Minister says crashed Germanwings plane's voice recorder damaged, but 'usable'". Fox News Channel. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Accident d'un Airbus A 320–211 immatriculé D-AIPX, vol GWI18G, survenu le 24 mars 2015" [Accident of an Airbus A320-211 registered D-AIPX, flight GWI18G, occurred on March 24, 2015]. BEA (in French). Archived from the original on 10 April 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- Hepher, Tim (25 March 2015). "Useable voice recording recovered from Alps crash: investigators". Paris. Reuters. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Germanwings crash: Co-pilot Lubitz 'researched suicide'". BBC News. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- Kulish, Nicholas; Eddy, Melissa; Clark, Nicola (2 April 2015). "Germanwings Pilot Searched Web About Suicide and Cockpit Doors, Officials Say". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Brown, Pamela; Smith-Spark, Laura; Pleitgen, Frederik (25 April 2015). "Germanwings crash: Co-pilot researched suicide methods, cockpit doors". CNN.

- "Germanwings Crash Site: Body Parts Found For All 150 Victims, French Prosecutor Says". International Business Times. 2 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- Clark, Nicola; Bilefsky, Dan (26 March 2015). "Fatal Descent of Germanwings Plane Was 'Deliberate,' French Authorities Say". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Flight 4U9525: Co-pilot put plane into descent, prosecutor says". CBC News. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Germanwings crash: What happened in the final 30 minutes". BBC News. 23 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Crash: How the Lock on the Cockpit Door Works". The New York Times. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Airbus A320 tragedy: cockpit recordings reveal co-pilot Andreas Lubitz crashed plane deliberately". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- Mouawad, Jad; Drew, Christopher (26 March 2015). "Post-Sept. 11, Cockpits Are Built to Protect From Outside Threats". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 June 2018.

- "Germanwings plane crash: Pilot locked out of cockpit before aircraft hit French Alps, says investigator, German state prosecutor". Australia: ABC News. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- Hinnant, Lori; McHugh, Dave (26 March 2015). "Alone at controls, co-pilot sought to 'destroy' the plane". MSN. Archived from the original on 26 January 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2015.

- "Germanwings plane crash: Co-pilot of flight appears to have crashed plane deliberately, French prosecutor says". Australia: ABC News. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Germanwings crash: Co-pilot Lubitz 'accelerated descent'". BBC News. 3 April 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- Clark, Nicola (3 April 2015). "Germanwings Co-Pilot Accelerated During Descent, Data From 2nd Recorder Shows". The New York Times. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- "Germanwings crash: Co-pilot Lubitz 'practised rapid descent'". BBC News. 6 May 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- "Preliminary Report" (PDF). Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'aviation civile. 24 March 2015. p. 29. Retrieved 29 February 2016.

He then intentionally modified the autopilot instructions to order the aeroplane to descend until it collided with the terrain.

- "Final report" (PDF). Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la sécurité de l'aviation civile. 13 March 2016. Retrieved 1 June 2019.

- "Airbus 320 crash: What we known about A320 co-pilot Andreas Lubitz". News.com.au. 28 March 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

but hid his illness from his employer and colleagues.

- "Germanwings plane crash: Police say 'significant discovery' at home of co-pilot Andreas Lubitz is not a suicide note". The Belfast Telegraph. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Germanwings plane crash: Co-pilot 'wanted to destroy plane'". BBC News. 27 March 2015.

- Pearson, Michael; Smith-Spark, Laura; Karimi, Faith (27 March 2015). "Germanwings co-pilot Andreas Lubitz declared 'unfit to work,' officials say". CNN. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

Germanwings co-pilot Andreas Lubitz was hiding an illness from his employers and had been declared "unfit to work" by a doctor, according to German authorities investigating what could have prompted the seemingly competent and stable pilot to steer his jetliner into a French mountain.

- "Germanwings crash: Co-pilot Lubitz 'hid illness'". BBC News. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Germanwings co-pilot Andreas Lubitz hid illness from employers – Business Insider". Business Insider. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- Kauh, Elaine (27 March 2015). "Investigators: Germanwings Co-pilot Concealed Medical Treatment". AVweb. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Flight 4U9525 co-pilot Andreas Lubitz 'hid illness' from employer". CBC News. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Germanwings plane crash: Co-pilot had been treated for suicidal tendencies, prosecutors say". ABC News (Australia). 31 March 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Reports: Antidepressants found at home of co-pilot Andreas Lubitz". CNN. 28 March 2015.

- "Andreas Lubitz 'repeatedly urged Germanwings captain to leave him alone' before setting A320 on path to French Alps crash". The Independent. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Keaton, Jamey (11 June 2015). "Germanwings Co-Pilot Feared Going Blind". ABC News. Archived from the original on 11 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Germanwings crash: French prosecutors open new probe". BBC News. 11 June 2015. Retrieved 30 August 2015.

- "Germanwings Flight 4U9525: Flight school knew of depressive episode". CBC News. 31 March 2015. Retrieved 1 April 2015.

- Calamur, Krishnadev; Chappell, Bill (30 March 2015). "Germanwings Crash: Co-Pilot Was Treated For Suicidal Tendencies". NPR. Retrieved 30 March 2015.

- Northam, Jackie (30 April 2015). "Documents Show FAA Questioned Mental Fitness of Germanwings Co-Pilot Andreas Lubitz". NPR. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "Germanwings co-pilot Andreas Lubitz feared going blind, visited many doctors". CNN. 11 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Germanwings Co-Pilot Contacted Dozens of Doctors". AVweb. 5 June 2015. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- "'The plane is disintegrated': 150 dead as Airbus A320 goes down in Southern France". National Post. Toronto, Canada. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Germanwings plane 4U 9525 crashes in French Alps – no survivors". BBC News. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Angela Merkel to travel to Germanwings crash site". ITV News. 24 March 2015. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- Botelho, Greg; Smith-Spark, Laura; Hanna, Jason (24 March 2015). "France plane crash: No survivors expected, French President says". CNN. Retrieved 24 March 2015.

- "Hollande, Merkel, Rajoy visit Germanwings A320 crash site". Radio France Internationale. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Germanwings Airbus A320 Crash: Haltern Weeps for Teens on Doomed Flight". NBC News. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Lufthansa boss says past hours 'darkest in 60-year history'". ITV News. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Distraught Germanwings pilots refuse to fly". CNN. 25 March 2015. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- "Germanwings Retires Flight Number 4U9525; New Flight Numbers from 25MAR15". airlineroute.net. Archived from the original on 29 March 2015. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "In reversal, crash-hit Lufthansa agrees to two-crew in cockpit rule". Fortune. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "Lufthansa will now keep two crew members in cockpits". CNN. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- Bryan, Victoria (28 March 2015). "Germanwings plane crash: Lufthansa to require two crew members in cockpit at all times". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 28 March 2015.

- "Reducing Risks After the Germanwings Crash". The New York Times. The Editorial Board. 26 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "China reasserts 'two in cockpit' rule it already had". Want China Times. 29 March 2015. Archived from the original on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Jingya, Zhang. "China clarifies rules following Alps plane crash – CCTV News – CCTV.com English". China Central Television. Retrieved 6 April 2015.

- "EU Regulator Recommends Tightening Cockpit Rules After Germanwings Crash". The Wall Street Journal. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 27 March 2015.

- "Statement on the Germanwings disaster". British Psychological Society. 27 March 2015. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- "EFPA News: European (Aviation) Psychologists react to crash Germanwings flight 4U 9525". Efpa.eu. 30 March 2015. Retrieved 1 May 2015.

- Niles, Russ (24 May 2015). "Random Pilot Mental Health Tests Proposed". AVweb. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Sheahan, Maria (22 May 2015). "Lufthansa CEO advocates random psych tests for pilots: FAZ". Reuters. Retrieved 5 September 2015.

- Le Poder, Laurence (2018). "Managing the emotional impact of disaster relief: The Gendarmerie Nationale and the crash of Germanwings Flight 952". Global Business & Organizational Excellence. 37 (4): 48–57. doi:10.1002/joe.21863.

- "Lufthansa offers victims' families initial 50,000 euros". Deutsche Welle. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 29 March 2015.

- Zubarev, Leonid (5 March 2013). "Montreal Convention of 1999 – new rules for international carriage by air". Globe Business Media Group. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- "Germanwings insurer sets aside $300 million to pay victims' families". Deutsche Welle. 31 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- "Lufthansa Expects Insurance Claim of $300 Million After Germanwings Plane Crash". The Wall Street Journal. 31 March 2015. Retrieved 31 March 2015.

- Rosenkranz, Justine; Suckow, Martin (11 March 2017). "Germanwings: Kein höheres Schmerzensgeld für Angehörige" [No higher compensation for relatives]. Tagesschau (in German). ARD. Archived from the original on 3 October 2017. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- "Flowers surround memorial for Alps crash victims". ITV. 27 March 2015. Retrieved 8 June 2015.

- Connolly, Kate (17 April 2015). "Germanwings flight relatives attend memorial service in Cologne". The Guardian. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- "Alps plane crash: Memorial service held in Cologne". BBC News. 17 April 2015. Retrieved 6 May 2015.

- "Germanwings crash: School victims return home". BBC News. 10 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- "Germanwings crash: Victims' remains land in Duesseldorf". BBC News. 10 June 2015. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- Rothwell, James (24 March 2017). "Father of Germanwings suicide pilot Andreas Lubitz angers victims' families as he protests son's innocence". The Daily Telegraph.

- "My son was not depressed,' father of Germanwings co-pilot says". Deutsche Welle. 24 March 2017.

- "Vater des Piloten erhebt schwere Vorwürfe gegen Ermittler" [Father of the pilot raises serious accusations against investigators]. Die Zeit (in German). 22 March 2017.

- "Vater von Andreas Lubitz: 'Unser Sohn war zum Zeitpunkt des Absturzes nicht depressiv'" [Our son was not depressed at the time of the crash]. Stern (in German). 24 March 2017.

- "Murder in the Skies". Mayday. Season 16. National Geographic Channel.

- "Season 16, Episode 7 'Murder in the Skies'". TV Guide. 24 January 2017. Retrieved 8 July 2017.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Germanwings Flight 9525. |

- Official memorial website - Lufthansa Group

- Indeepsorrow.com at the Wayback Machine (archive index) memorial site (also by Lufthansa Group)

- "Final Investigation Report: Accident to the Airbus A320-211, registered D-AIPX and operated by Germanwings, flight GWI18G, on 03/24/15 at Prads-Haute-Bléone". Bureau d'Enquêtes et d'Analyses pour la Sécurité de l'Aviation Civile. 13 March 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2016.

- "Task Force on Measures Following the Accident of Germanwings Flight 9525" (PDF) (Final Report). European Aviation Safety Agency. July 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2016.

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network