Airbus A320 family

The Airbus A320 family are narrow-body airliners designed and produced by Airbus. The A320 was launched in March 1984, first flew on 22 February 1987, and was introduced in April 1988 by Air France. The first member of the family was followed by the longer A321 (first delivered in January 1994), the shorter A319 (April 1996), and the even shorter A318 (July 2003). Final assembly takes place in Toulouse in France; Hamburg in Germany; Tianjin in China since 2009; and in Mobile, Alabama in the United States since April 2016.

| A320 family A318/A319/A320/A321 | |

|---|---|

_crop.jpg) | |

| A Jetstar Airways A320 in flight. The A320 is a low wing airliner with twin underwing turbofans | |

| Role | Single-aisle jet airliner |

| National origin | Multi-national[lower-alpha 1] |

| Manufacturer | Airbus |

| First flight | 22 February 1987 |

| Introduction | 18 April 1988 with Air France[1] |

| Status | In service |

| Primary users | American Airlines[lower-alpha 2] |

| Produced | 1986–present |

| Number built | 9,373 as of 31 May 2020[3] |

| Program cost | £2 billion ($2.8 billion, 1984 – Flight International estimate)[4](£6 billion today) or 5.486 Bn FRF (1988)[5] |

| Unit cost |

|

| Variants | |

| Developed into | Airbus A320neo family |

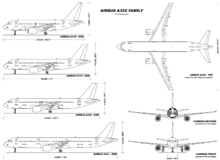

The twinjet has a six-abreast cross-section and is powered by either CFM56 or IAE V2500 turbofans, except the CFM56/PW6000 powered A318. The family pioneered the use of digital fly-by-wire and side-stick flight controls in airliners. Variants offer maximum take-off weights from 68 to 93.5 t (150,000 to 206,000 lb), to cover a 5,740–6,940 km (3,100–3,750 nmi) range. The 31.4 m (103 ft) long A318 typically accommodates 107 to 132 passengers. The 124-156 seats A319 is 33.8 m (111 ft) long. The A320 is 37.6 m (123 ft) long and can accommodate 150 to 186 passengers. The 44.5 m (146 ft) A321 offers 185 to 230 seats. The Airbus Corporate Jets are business jet versions.

In December 2010, Airbus announced the re-engined A320neo (new engine option), which entered service with Lufthansa in January 2016. With more efficient turbofans and improvements including sharklets, it offers up to 15% better fuel economy. Earlier A320s are now called A320ceo (current engine option).

In October 2019, it surpassed the Boeing 737 to become the highest-selling airliner. As of January 2020, a total of 9,273 aircraft have been delivered to more than 330 operators including low-cost carriers, with 8,814 aircraft in service. American Airlines is the largest operator with 414 aircraft.[lower-alpha 2] Orders pending were 6,068, for a total of 15,315 orders. The A320ceo initially competed with the MD-80 and the 737 Classic, then the MD-90 and the 737 Next Generation, while the 737 MAX is Boeing's response to the A320neo.

Development

Origins

When Airbus designed the Airbus A300 during the late 1960s and early 1970s, it envisaged a broad family of airliners with which to compete against Boeing and Douglas, two established US aerospace manufacturers. From the moment of formation, Airbus had begun studies into derivatives of the Airbus A300B in support of this long-term goal.[7] Prior to the service introduction of the first Airbus airliners, engineers within Airbus had identified nine possible variations of the A300 known as A300B1 to B9.[8] A 10th variation, conceived in 1973, later the first to be constructed, was designated the A300B10.[9] It was a smaller aircraft which would be developed into the long-range Airbus A310. Airbus then focused its efforts on the single-aisle market, which was dominated by the 737 and McDonnell Douglas DC-9.

Plans from a number of European aircraft manufacturers called for a successor to the relatively successful BAC One-Eleven, and to replace the 737-200 and DC-9.[10] Germany's MBB (Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm), British Aircraft Corporation, Sweden's Saab and Spain's CASA worked on the EUROPLANE, a 180- to 200-seat aircraft.[10][11] It was abandoned after intruding on A310 specifications.[11] VFW-Fokker, Dornier and Hawker Siddeley worked on a number of 150-seat designs.[10]

The design within the JET study that was carried forward was the JET2 (163 passengers), which then became the Airbus S.A1/2/3 series (Single Aisle), before settling on the A320 name for its launch in 1984. Previously, Hawker Siddeley had produced a design called the HS.134 "Airbus" in 1965, an evolution of the HS.121 (formerly DH.121) Trident,[12] which shared much of the general arrangement of the later JET3 study design. The name "Airbus" at the time referred to a BEA requirement, rather than to the later international programme.

Design effort

In June 1977 a new Joint European Transport (JET) programme was set up, established by BAe, Aerospatiale, Dornier and Fokker.[13][14] It was based at the then British Aerospace (formerly Vickers) site in Weybridge, Surrey, UK. Although the members were all of Airbus' partners, they regarded the project as a separate collaboration from Airbus.[15] This project was considered the forerunner of Airbus A320, encompassing the 130- to 188-seat market, powered by two CFM56s.[10] It would have a cruise speed of Mach 0.84 (faster than the Boeing 737).[10] The programme was later transferred to Airbus, leading up to the creation of the Single-Aisle (SA) studies in 1980, led by former leader of JET programme, Derek Brown.[11] The group looked at three different variants, covering the 125- to 180-seat market, called SA1, SA2 and SA3.[10] Although unaware at the time, the consortium was producing the blueprints for the A319, A320 and A321, respectively.[11] The single-aisle programme created divisions within Airbus about whether to design a shorter-range twinjet rather than a longer-range quadjet wanted by the West Germans, particularly Lufthansa.[10][15] However, works proceeded, and the German carrier would eventually order the twinjet.

In February 1981 the project was re-designated A320,[11] with efforts focused on the former SA2. During the year, Airbus worked with Delta Air Lines on a 150-seat aircraft envisioned and required by the airline. The A320 would carry 150 passengers over 5,280 or 3,440 km (2,850 or 1,860 nmi) using fuel from wing fuel tanks only.[11] The Dash 200 had centre tank activated, increasing fuel capacity from 15,590 to 23,430 L (3,429 to 5,154 imp gal).[16] They would measure 36.04 and 39.24 m (118 ft 3 in and 128 ft 9 in), respectively.[11] Airbus considered a fuselage diameter of "the Boeing 707 and 727, or do something better" and settled on a wider cross-section with a 3.7 m (12 ft 2 in) internal width, compared to Boeing's 3.45 m (11 ft 4 in).[10] Although heavier, this allowed to compete more effectively with the 737. The A320 wing went through several stages of design, finally settling on 33.91 m (111 ft 3 in).[16]

National shares

The UK, France and West Germany wanted the responsibility of final assembly and the associated duties, known as "work-share arguments". The Germans requested an increased work-share of 40%, while the British wanted the major responsibilities to be swapped around to give partners production and research and development experience. In the end, British work-share was increased from that of the two previous Airbuses.[15]

France was willing to commit to a launch aid, or subsidies, while the Germans were more cautious.[15] The UK government was unwilling to provide funding for the tooling requested by British Aerospace (BAe) and estimated at £250 million, it was postponed for three years.[16] On 1 March 1984 the government and the manufacturer agreed that £50 million would be paid whether the A320 would fly or not, while the rest would be paid as a levy on each aircraft sold.[15]

Launch

_FAB_SEP88_(13753510323).jpg)

The programme was launched on 2 March 1984.[17] At this time, Airbus had 96 orders.[18]:48 Air France was its first customer with a "letter of intent" for 25 A320s and an option for 25 more at the 1981 Paris air show.[19] In October 1983, British Caledonian placed seven firm orders, bringing total orders to more than 80.[20] Cyprus Airways became the first to place order for V2500-powered A320s in November 1984, followed by Pan Am with 16 firm orders and 34 options in January 1985, then Inex Adria.[18]:49 One of the most significant orders was when Northwest Airlines placed an order for 100 A320s in October 1986, later confirmed at the 1990 Farnborough Airshow, powered by CFM56 engines.[18]:49–50

During the A320 development programme, Airbus considered propfan technology, backed by Lufthansa.[15] At the time unproven, it was essentially a fan placed outside the engine nacelle, offering speed of a turbofan at turboprops economics; eventually, Airbus stuck with turbofans.

Power on the A320 would be supplied by two CFM56-5-A1s rated at 25,000 lbf (111.2 kN).[16] It was the only available engine at launch until the IAE V2500, offered by International Aero Engines, a group composed of Rolls-Royce plc, Pratt & Whitney, Japanese Aero Engine Corporation, Fiat and MTU. The first V2500 variant, the V2500-A1, has a thrust output of 25,000 pounds-force (110 kN),[21] hence the name. It is 4% more efficient than the CFM56, with cruise thrust specific fuel consumption for the -A5 at 0.574 and 0.596 lb/lbf/h (16.3 and 16.9 g/kN/s) for the CFM56-5A1.[22]

Introduction

_F-GFKQ_-_MSN_002_(10655931213).jpg)

In presence of then French Prime Minister Jacques Chirac and the Prince and Princess of Wales, the first A320 was rolled out of the final assembly line on 14 February 1987 and made its maiden flight on 22 February in 3 hours and 23 minutes from Toulouse.[23] The flight test programme took 1,200 hours on 530 flights. European Joint Aviation Authorities certification was delivered on 26 February 1988.[18]:50 The first A320 was delivered to Air France on 28 March 1988.[24]

Stretching the A320: A321

The first derivative of the A320 was the Airbus A321, also known as the Stretched A320, A320-500 and A325.[11][25] Its launch came on 24 November 1988 after commitments for 183 aircraft from 10 customers were secured.[11][26] The aircraft would be a minimum-changed derivative, apart from a number of minor modifications to the wing, and the fuselage stretch itself. The wing would incorporate double-slotted flaps and minor trailing edge modifications,[11] increasing the wing area from 124 m2 (1,330 sq ft) to 128 m2 (1,380 sq ft).[27] The fuselage was lengthened by four plugs (two ahead and two behind the wings), giving the A321 an overall length of 6.94 metres (22 ft 9 in) longer than the A320.[11][28][29] The length increase required the overwing exits of the A320 to be enlarged and repositioned in front of and behind the wings.[16] The centre fuselage and undercarriage were reinforced to accommodate the increase in maximum takeoff weight of 9,600 kg (21,200 lb), taking it to 83,000 kg (183,000 lb).[11]

Final assembly for the A321 would be, as a first for any Airbus, carried out in Germany (then West Germany).[30] This came after a dispute between the French, who claimed the move would incur $150 million (€135 million) in unnecessary expenditure associated with the new plant,[11] and the Germans, arguing it would be more productive for Airbus in the long run. The second production line was located at Hamburg, which would also subsequently produce the smaller Airbus A319 and A318. For the first time, Airbus entered the bond market, through which it raised $480 million (€475 million) to finance development costs.[26] An additional $180 million (€175 million) was borrowed from European Investment Bank and private investors.[11]

The maiden flight of the Airbus A321 came on 11 March 1993, when the prototype, registration F-WWIA, flew with IAE V2500 engines; the second prototype, equipped with CFM56-5B turbofans, flew in May. Lufthansa and Alitalia were the first to order the stretched Airbuses, with 20 and 40 aircraft requested, respectively. The first of Lufthansa's V2500-A5-powered A321s arrived on 27 January 1994, while Alitalia received its first CFM56-5B-powered aircraft on 22 March.

Shrinking the A320: A319

.jpg)

The A319 is the next derivative of the baseline A320. The design is a "shrink" with its origins in the 130- to 140-seat SA1, part of the Single-Aisle studies.[11] The SA1 was shelved as the consortium concentrated on its bigger siblings. After healthy sales of the A320/A321, Airbus re-focused on what was then known as the A320M-7, meaning A320 minus seven fuselage frames.[16] It would provide direct competition for the 737-300/-700.[11] The shrink was achieved through the removal of four fuselage frames fore and three aft of the wing, cutting the overall length by 3.73 metres (12 ft 3 in).[28][31][32] Consequently, the number of overwing exits was reduced from four to two. The bulk-cargo door was replaced by an aft container door, which can take in reduced height LD3-45 containers.[31] Minor software changes were made to accommodate the different handling characteristics; otherwise the aircraft is largely unchanged. Power is provided by the CFM56-5A or V2500-A5, derated to 98 kN (22,000 lbf), with option for 105 kN (24,000 lbf) thrust.[33]

Airbus began offering the new model from 22 May 1992, with the actual launch of the $275 million (€250 million) programme occurring on 10 June 1993;[31][11][8] the A319's first customer was ILFC, who signed for six aircraft. On 23 March 1995, the first A319 underwent final assembly at Airbus' German plant in Hamburg, where the A321s are also assembled. It was rolled out on 24 August 1995, with the maiden flight the following day.[16] The certification programme would take 350 airborne hours involving two aircraft; certification for the CFM56-5B6/2-equipped variant was granted in April 1996, after which qualification for the V2524-A5 started the following month.[11]

Delivery of the first A319, to Swissair, took place on 25 April 1996, entering service by month's end.[11] In January 1997, an A319 broke a record during a delivery flight by flying 3,588 nautical miles (6,645 km) the great circle route to Winnipeg, Manitoba from Hamburg, in 9 hours 5 minutes.[11] The A319 has proved popular with low-cost airlines such as EasyJet, who has orders for 172, with 172 delivered.[3]

Second shrink: A318

The A318 was born out of mid-1990 studies between Aviation Industries of China (AVIC), Singapore Technologies Aerospace, Alenia and Airbus on a 95- to 125-seat aircraft project. The programme was called the AE31X, and covered the 95-seat AE316 and 115- to 125-seat AE317.[11] The former would have had an overall length of 31.3 m (102 ft 8 in), while the AE317 was longer by 3.2 m (10 ft 6 in), at 34.5 m (113 ft 2 in).[34] The engines were to be supplied from two Rolls-Royce BR715s, CFM56-9s, or the Pratt & Whitney PW6000s;[11][34] with the MTOW of 53.3 t (118,000 lb) for the smaller version and 58 t (128,000 lb) for the AE317, the thrust requirement were 77.9–84.6 kN (17,500–19,000 lbf) and 84.6–91.2 kN (19,000–20,500 lbf), respectively.[34] Range was settled at 5,200 km (2,800 nmi) and 5,800 km (3,100 nmi) for the high gross weights of both variants.[34] Both share a wingspan of 31.0 m (101 ft 8 in)[34] and a flight deck similar to that of the A320 family. Costing $2 billion (€1.85 billion) to develop, aircraft production was to take place in China.[11]

Simultaneously, Airbus was developing Airbus A318. In early 1998, Airbus revealed its considerations of designing a 100-seat aircraft based on the A320. The AE31X project was terminated by September 1998, after which Airbus officially announced an aircraft of its own, the A318,[11] at that year's Farnborough Airshow.[8] The aircraft is the smallest product of Airbus's product range, and was developed coincidentally at the same time as the largest commercial aircraft in history, the Airbus A380. First called A319M5 in as early as March 1995, it was shorter by 0.79-metre (2 ft 7 in) ahead of the wing and 1.6 metres (5 ft 3 in) behind.[8] These cuts reduced passenger capacity from 124 on the A319 to 107 passengers in a two-class layout.[35] Range was 5,700 kilometres (3,100 nmi), or 5,950 kilometres (3,210 nmi) with upcoming Sharklets.[35]

The 107-seater was launched on 26 April 1999 with the options and orders count at 109 aircraft.[8] After three years of design, the maiden flight took place at Hamburg on 15 January 2002.[36] Tests on the lead engine, the Pratt & Whitney PW6000, revealed worse-than-expected fuel consumption.[37] Consequently, Pratt & Whitney abandoned the five-stage high-pressure compressor (HPC) for the MTU-designed six-stage HPC. The 129 order book for the A318 shrunk to 80 largely because of switches to other A320 family members.[37] After 17 months of flight certification, during which 850 hours and 350 flights were accumulated, JAA certification was obtained for the CFM56-powered variant on 23 May 2003.[37] On 22 July 2003, first delivery for launch customer Frontier Airlines occurred,[8] entering service before the end of the month.

Production

.jpg)

The Toulouse Blagnac final assembly line builds A320s, whereas the Hamburg Finkenwerder final assembly line builds A318s, A319s, and A321s. The Airbus factory in Tianjin, China assembles A319s, A320s, and A321s; A320s and A321s are also assembled at the Airbus Americas factory in Mobile, Alabama.[38] Airbus produced a total of 42 A320s per month in 2015, and expects to increase to 50 per month in 2017.[39]

As Airbus targets a 60 monthly global production rate by mid-2019, the Tianjin line delivered 51 in 2016 and it could assemble six per month from four as it starts producing A320neos in 2017; 147 Airbus were delivered in 2016 in China, 20% of its production, mostly A320-family, a 47% market share as the country should become the world's largest market ahead of the US before 2027.[40]

In June 2018, along a larger and modernised delivery centre, Airbus inaugurated its fourth Hamburg production line, with two seven-axis robots to drill 80% of fuselage upper side holes, autonomous mobile tooling platforms and following Design Thinking principles.[41] By January 2019, Mobile was outputting 4.5 A320s per month, raising to five by the end of the year.[42]

In September 2019, Airbus reached a milestone with the delivery of the 9000th A320-family aircraft to Easyjet. In October 2019, Airbus inaugurated a highly automated fuselage structure assembly line for A320 Family aircraft in Hamburg, showcasing an evolution in Airbus' industrial production system.[43] Production rates continue to rise, and Airbus aims to reach a production rate of 63 aircraft per month by 2021, which would result in the 10,000th delivery occurring early that year.[44]

A320 Enhanced

Improvements

In 2006, Airbus started the A320 Enhanced (A320E) programme as a series of improvements targeting a 4–5% efficiency gain with large winglets (2%), aerodynamic refinements (1%), weight savings and a new aircraft cabin.[45] Engine improvements reducing fuel consumption by 1% were fitted into the A320 in 2007 with the CFM56 Tech Insertion[46] and in 2008 with the V2500Select (One).[47]

Sharklets

In 2006, Airbus tested three styles of winglet intended to counteract the wing's induced drag and wingtip vortices more effectively than the previous wingtip fence. The first design type to be tested was developed by Airbus and was based on work done by the AWIATOR programme.[48] The second type of winglet incorporated a more blended design and was designed by Winglet Technology, a company based in Wichita, Kansas. Two aircraft were used in the flight test evaluation campaign – the prototype A320, which had been retained by Airbus for testing, and a new build aircraft which was fitted with both types of winglets before it was delivered to JetBlue.

Despite the anticipated efficiency gains and development work, Airbus announced that the new winglets will not be offered to customers, claiming that the weight of the modifications required would negate any aerodynamic benefits.[49] On 17 December 2008, Airbus announced it was to begin flight testing an existing blended winglet design developed by Aviation Partners Inc. as part of an A320 modernisation programme using the A320 prototype.[50]

Airbus launched the sharklet blended wingtip device during the November 2009 Dubai Airshow: installation adds 200 kg (440 lb) but offers a 3.5% fuel burn reduction on flights over 2,800 km (1,500 nmi).[51] They save US$220,000 and 700 t of CO2 per aircraft per year.[52] The 2.5 metres (8 ft 2 in) tall devices are manufactured by Korean Air Aerospace Division.[53] The winglets increase efficiency by decreasing lift-induced drag.

In December 2011, Airbus filed suit in the western district of Texas over Aviation Partners' claims of infringement of its patents on winglet design and construction which were granted in 1993. Airbus' lawsuit seeks to reject responsibility to pay royalties to Aviation Partners for using its designs, despite work performed together with both parties to develop advanced winglets for the A320neo.[54]

The first sharklet-equipped A320 was delivered to AirAsia on 21 December 2012, offering a 450 kg (990 lb) payload increase or 190 km (100 nmi) longer range at the original payload.[55]

Cabin

In 2007, Airbus introduced a new enhanced, quieter cabin with better luggage storage and a more modern look and feel, and a new galley reduces weight, increases revenue space and improves ergonomics and design for food hygiene and recycling.[56] It offers a new air purifier with filters and a catalytic converter removing unpleasant smells from the air before it is pumped into the cabin and LEDs for ambience lighting and PSU.[57]

Offering 10% more overhead bin volume, more shoulder room, a weight reduction, a new intercom and in-flight entertainment system, noise reduction and slimmer PSU, the enhanced Cabin can be retrofitted.[58] The flight crew controls the cabin through touchscreen displays.[59]

New Engine Option

The A320neo (neo for new engine option) is a development launched on 1 December 2010, it made its first flight on 25 September 2014 and it was introduced by Lufthansa on 25 January 2016. Re-engined with CFM International LEAP-1A or Pratt & Whitney PW1000G engines and with large sharklets, it should be 15% more fuel efficient. Three variants are based on the previous A319, A320 and A321. Airbus received 6,031 orders by March 2018 and delivered 318 by May 2018. The original family is renamed A320ceo, for current engine option.

Design

The Airbus A320 family are narrow-body (single-aisle) aircraft with a retractable tricycle landing gear and are powered by two wing pylon-mounted turbofan engines. After the oil price rises of the 1970s, Airbus needed to minimise the trip fuel costs of the A320. To that end, it adopted composite primary structures, centre-of-gravity control using fuel, glass cockpit (EFIS) and a two-crew flight deck.

Airbus claimed the 737-300 burns 35% more fuel and has a 16% higher operating cost per seat than the V2500-powered A320.[60] A 150-seat A320 burns 11,608 kg (25,591 lb) of jet fuel over 3,984 km (2,151 nmi) (between Los Angeles and New York City), or 2.43 L/100 km (97 mpg‑US) per seat with a 0.8 kg/L fuel.[61] Its wing is long and thin, offering better aerodynamic efficiency because of the higher aspect ratio than the competing 737 and MD-80.

Airframe

The Airbus A320 family are low-wing cantilever monoplanes with a conventional empennage with a single vertical stabilizer and rudder. Its wing sweep is 25 degrees. Compared to other airliners of the same class, the A320 features a wider single-aisle cabin of 3.95 metres (156 in) outside diameter,[28] compared to 3.8 m (148 in) of the Boeing 737 or 757, and larger overhead bins. Its cargo hold can accommodate Unit Load Devices containers.

The A320 airframe includes composite materials and aluminium alloys to save weight and reduce the total number of parts to decrease the maintenance costs.[62] Its tail assembly is made almost entirely of such composites by CASA, who also builds the elevators, main landing gear doors, and rear fuselage parts.[11]

Flight deck

It includes a full glass cockpit rather than the hybrid versions found in previous airliners. The A320's flight deck is equipped with Electronic Flight Instrument System (EFIS) with side-stick controllers. The A320 features an Electronic Centralised Aircraft Monitor (ECAM) which gives the flight crew information about all the systems of the aircraft. The only analogue instruments were the radio-magnetic indicator and brake pressure indicator.

Since 2003, the A320 features liquid crystal display (LCD) units in its flight deck instead of the original cathode ray tube (CRT) displays. These include the main displays and the backup artificial horizon, which was previously an analog display.[63]

Airbus offers an avionics upgrade for older A320, the In-Service Enhancement Package, to keep them updated.[64] Digital head-up displays are available.[65]

The A320 retained the dark cockpit (where an indicator is off when its system is running; useful for drawing attention to dysfunctions when an indicator is lit) from the A310, the first widebody designed to be operated without a flight engineer and influenced by Bernard Ziegler, first Airbus CEO Henri Ziegler's son.[66]

Fly-by-wire

The A320 is the world's first airliner with digital fly-by-wire (FBW) flight control system: input commands through the side-stick are interpreted by flight control computers and transmitted to flight control surfaces within the flight envelope protection; in the 1980s the computer-controlled dynamic system of the Dassault Mirage 2000 fighter cross-fertilised the Airbus team which tested FBW on an A300.[67] At its introduction, fly-by-wire and flight envelope protection was a new experience for many pilots.

All following Airbuses have similar human/machine interface and systems control philosophy to facilitate cross-type qualification with minimal training. For Roger Béteille, then Airbus president, introducing fly-by-wire with flight envelope protection was one of the most difficult decisions he had ever made, explaining: "Either we were going to be first with new technologies or we could not expect to be in the market."[67]

Early A320s used the Intel 80186 and Motorola 68010.[68] In 1988, the flight management computer contained six Intel 80286 CPUs, running in three logical pairs, with 2.5 megabytes of memory.[69]

Engines

The suppliers providing turbofan engines for the A320 series are CFM International with the CFM56, International Aero Engines offering its V2500, and Pratt & Whitney's PW6000 engines available only for the A318.[70]

.jpg) The CFM56, with an unmixed exhaust, is available on all variants

The CFM56, with an unmixed exhaust, is available on all variants.jpg) The IAE V2500, with a mixed exhaust, equips the larger variants

The IAE V2500, with a mixed exhaust, equips the larger variants_landed_at_Congonhas-S%C3%A3o_Paulo_International_Airport_(1)_(cropped).jpg) The PW6000 is available on the smallest A318

The PW6000 is available on the smallest A318

Operational history

The Joint Aviation Authorities (JAA) issued the type certificate for the A320 on 26 February 1988. After entering the market on 18 April 1988 with Air France, Airbus then expanded the A320 family rapidly, launching the 185-seat A321 in 1989 and first delivered it in 1994; launching the 124-seat A319 in 1993 and delivering it in 1996; and launching the 107-seat A318 in 1999 with first deliveries in 2003.[71]

Competition

.jpg)

The A320 family was developed to compete with the Boeing 737 Classics (-300/-400/-500) and the McDonnell Douglas MD-80/90 series, and has since faced challenges from the Boeing 737 Next Generation (-600/-700/-800/-900) and the 717 during its two decades in service. As of 2010, as well as the 737, the A320 family faces competition from Embraer's E-195 (to the A318), and the CSeries being developed by Bombardier[72] to the A318/A319.

Airbus has delivered 8,605 A320 family aircraft since their certification/first delivery in early 1988, with another 6,056 on firm order (as of 31 December 2018).[3] In comparison, Boeing has shipped 10,444 737 series since late 1967, with 8,918[73] of those deliveries since March 1988,[74] and has a further 4,763 on firm order (as of 31 December 2018).[75]

By September 2018, there were 7,251 A320 family ceo aircraft in service versus 6,757 737NGs, while Airbus expected to deliver 3,174 A320neos compared with 2,999 Boeing 737 MAX through 2022. Airbus sold the A320 well to low-cost startups and offering a choice of engines could make them more attractive to airlines and lessors than the single sourced 737, but CFM engines are extremely reliable. The six-month head-start of the A320neo allowed Airbus to rack up 1,000 orders before Boeing announced the MAX. The A321 has outsold the 737-900 three to one, as the A321neo is again dominating the 737-9 MAX, to be joined by the 737-10 MAX.[78]

Maintenance

A Checks are every 750 flight hours and structural inspections are at six- and 12-year intervals.

Replacement airliner

In 2006, Airbus was studying a future replacement for the A320 series, tentatively dubbed NSR, for "New Short-Range aircraft".[79] The follow-on aircraft to replace the A320 was named A30X. Airbus North America President Barry Eccleston stated that the earliest the aircraft could have been available was 2017.[80] In January 2010, John Leahy, Airbus's chief operating officer-customers, stated that an all-new single-aisle aircraft was unlikely to be constructed before 2024 or 2025.[81]

Variants

Overview

The baseline A320 has given rise to a family of aircraft which share a common design but with passenger capacity ranges from 100, on the A318,[35] to 220, on the A321.[29] They compete with the 737, 757, and 717. Because the four variants share the same flight deck, all have the same pilot type rating. Today all variants are available as corporate jets. An A319 variant known as A319LR is also developed. Military version like A319 MPA also exists. American Airlines is the world's largest airline operator of the A320 family of aircraft with 392 aircraft in service as of 30 September 2017.[3]

Technically, the name "A320" only refers to the original mid-sized aircraft, but it is often informally used to indicate any of the A318/A319/A320/A321 family. All variants are able to be ETOPS (Extended-range Twin-engine Operational Performance Standards) certified for 180 minutes since 2004 (EASA) and 2006 (FAA).[82] With launch of the new Airbus A320neo project, the previous members of the Airbus A320 family received the "current engine option" or "CEO" name.

A320

The A320 series has two variants, the A320-100 and A320-200. Only 21 A320-100s were produced.[11] These aircraft, the first to be manufactured, were delivered to Air Inter – later acquired by Air France – and British Airways as a result of an order from British Caledonian made prior to its acquisition.

The primary changes of the -200 over the -100 are wingtip fences and increased fuel capacity for increased range. Indian Airlines used its first 31 A320-200s with double-bogie main landing gear for airfields with poor runway condition which a single-bogie main gear could not manage.

Powered by two CFM International CFM56-5s or IAE V2500s with thrust ratings of 98–120 kN (22,000–27,000 lbf), its typical range with 150 passengers is 3,300 nmi / 6,100 km.[28] A total of 4,512 of the A320ceo model have been delivered, with 220 remaining on order as of 30 September 2017.[3] The closest Boeing competitor is the 737-800.[83]

In 1988, the value of a new A320 was $30 million, reaching $40 million by the end of the 1990s, a 30% increase lower than the inflation, it dipped to $37 million after 2001, then peaked to $47 million in 2008, and stabilised at $40–42 million until the transition to the A320neo.[84]

A321

.jpg)

As the A320 began operations in 1988, the A321 was launched as its first derivative.[11] The A321 fuselage is stretched by 6.93 metres (22 ft 9 in) with a 4.27 m (14 ft 0 in) front plug immediately forward of wing and a 2.67 m (8 ft 9 in) rear plug.[8] The A321-100 maximum takeoff weight is increased by 9,600 kg (21,200 lb) to 83,000 kg (183,000 lb).[11] To maintain performance, double-slotted flaps were included, in addition to increasing the wing area by 4 m2 (43 sq ft), to 128 m2 (1,380 sq ft).[27] The maiden flight of the first of two prototypes came on 11 March 1993.[16] The A321-100 entered service in January 1994 with Lufthansa.

As the A321-100 range was reduced compared to the A320, the heavier and longer range A321-200 development was launched in 1995. This is achieved through higher thrust engines (V2533-A5 or CFM56-5B3), minor structural strengthening, and an increase in fuel capacity with the installation of one or two optional 2,990 L (790 US gal) tanks in the rear underfloor hold.[8] Its fuel capacity is increased to 30,030 L (7,930 US gal) and its maximum takeoff weight to 93,000 kg (205,000 lb). It first flew in December 1996 and entered service with Monarch Airlines in April 1997.

Its closest Boeing competitors are the 737-900/900ER,[83] and the 757-200.[27] A total of 1,562 of the A321ceo model have been delivered, with 231 remaining on order as of 30 September 2017.[3]

A319

The A319 is 3.73 m (12 ft 3 in) shorter than the A320.[28][31][32] Also known as the A320M-7, it is a shortened, minimum-change version of the A320 with four frames fore of the wing and three frames aft of the wing removed. With a similar fuel capacity as the A320-200 and fewer passengers, the range with 124 passengers in a two-class configuration extends to 6,650 km (3,590 nmi), or 6,850 km (3,700 nmi) with the "Sharklets".[32] Four propulsion options available on the A319 are the 23,040–24,800 lbf (102.5–110.3 kN) IAE V2500, or the 22,000–27,000 lbf (98–120 kN) CFM56.[8] Although identical to those of the A320, these engines are derated because of the A319's lower MTOW.

The A319 was developed at the request of Steven F. Udvar-Házy, the former president and CEO of ILFC.[86] The A319's launch customer, in fact, was ILFC, which had placed an order for six A319s by 1993.[11] Anticipating further orders by Swissair and Alitalia, Airbus decided to launch the programme on 10 June 1993. Final assembly of the first A319 began on 23 March 1995[16] and it was first introduced with Swissair in April 1996. The direct Boeing competitor is the Boeing 737-700.

A total of 1,460 of the A319ceo model have been delivered with 24 remaining on order as of 30 September 2017.[3] A 1998 A319 value was $35 million new, was halved by 2009, and reached scrap levels by 2019.[87]

A319CJ

.jpg)

The A319CJ (rebranded ACJ319) is the corporate jet version of the A319. It incorporates removable extra fuel tanks (up to six additional center tanks) which are installed in the cargo compartment, and an increased service ceiling of 12,500 m (41,000 ft).[88] Range with eight passengers' payload and auxiliary fuel tanks (ACTs) is up to 11,000 kilometres (6,000 nmi).[89][90] Upon resale, the aircraft can be reconfigured as a standard A319 by removing its extra tanks and corporate cabin outfit, thus maximising its resale value. It was formerly also known as the ACJ, or Airbus Corporate Jet, while starting with 2014 it has the marketing designation ACJ319.

The aircraft seats up to 39 passengers, but may be outfitted by the customers into any configuration. Tyrolean Jet Services Mfg. GmbH & CO KG, MJET and Reliance Industries are among its users. The A319CJ competes with other ultralarge-cabin corporate jets such as the Boeing 737-700-based Boeing Business Jet (BBJ) and Embraer Lineage 1000, as well as with large-cabin and ultralong-range Gulfstream G650, Gulfstream G550 and Bombardier's Global 6000. It is powered by the same engine types as the A320. The A319CJ was used by the Escadron de Transport, d'Entraînement et de Calibration which is in charge of transportation for France's officials and also by the Flugbereitschaft of the German Air Force for transportation of Germany's officials. An ACJ serves as a presidential or official aircraft of Armenia,[91] Azerbaijan, Brazil, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Germany, Italy,[92] Malaysia, Slovakia, Thailand, Turkey, Ukraine, and Venezuela.

A318

.jpg)

The Airbus A318 is the smallest member of the Airbus A320 family. The A318 carries up to 132 passengers and has a maximum range of 5,700 km (3,100 nmi). The aircraft entered service in July 2003 with Frontier Airlines, and shares a common type rating with all other Airbus A320 family variants, allowing existing A320 family pilots to fly the aircraft without the need for further training. It is the largest commercial aircraft certified by the European Aviation Safety Agency for steep approach operations, allowing flights at airports such as London City Airport. Relative to other Airbus A320 family variants, the A318 has sold in only small numbers with total orders for only 80 aircraft placed as of 31 October 2015.

Freighter

.jpg)

A programme to convert A320 and A321 aircraft into freighters was set up by Airbus Freighter Conversion GmbH. Airframes would be converted by EADS EFW in Dresden, Germany, and Zhukovsky, Russia. The launch customer AerCap signed a firm contract on 16 July 2008 to convert 30 of AerCap's passenger A320/A321s into A320/A321P2F (passenger to freighter). However, on 3 June 2011, Airbus announced all partners would end the passenger to freighter programme, citing high demand for used airframes for passenger service.[93]

On 17 June 2015 ST Aerospace signed agreements with Airbus and EADS EFW for a collaboration to launch the A320/A321 passenger-to-freighter (P2F) conversion programme.[94] In August 2019, Qantas was announced as the launch operator for the A321P2F converted freighter, for Australia Post, with up to three aircraft to be introduced in October 2020.[95] The initial converted aircraft first flew on 22 January 2020, to be delivered to Vallair, and it secured EASA supplementary type certificate in February. It should replace older converted Boeing 757s with 14 positions on the main deck and 10 on the lower, lifting up to 27.9 t (62,000 lb) over 4,300 km (2,300 nmi). Airbus sees a market for 1,000 narrowbody conversions over the 2020-2040 period.[96]

Operators

_-_Quintin_Soloviev.jpg)

As of 31 December 2017, 7,630 Airbus A320-family aircraft (all variants, including the A320neo family) remained in commercial service with over 330 airline operators. This includes 67 A318, 1,446 A319ceo, 4,270 A320ceo, 229 A320neo, 1,598 A321ceo and 20 A321neo aircraft.[3] Air France and British Airways are the only operators to operate all four variants of the A320ceo family.

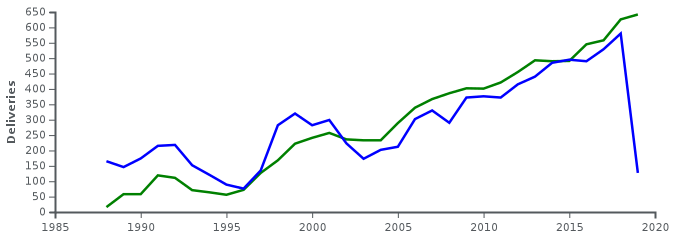

Orders and deliveries

It ranked as the world's fastest-selling jet airliner family according to records from 2005 to 2007.[97]

By end of October 2019, the backlog of A320ceo fell to 78: 7 A319s, 24 A320s and 47 A321s; as Airbus delivered 87 A320ceo variants over the first 10 months of 2019 compared to 394 A320neo variants. With the backlog was over the 6,000 mark again, the A320 family total orders reached 15,193, surpassing the 15,136 Boeing 737 orders amid the Boeing 737 MAX groundings, becoming the highest-selling airliner, while 10,563 of the 737 series have been delivered since 1965, nearly 1,500 more than the 9,086 A320-family aircraft delivered since 1988.[98]

By end of May 2020, the A320ceo backlog fell further to 60: 6 A319s, 20 A320s and 34 A321s; as Airbus delivered 6 A320ceo variants over the first 5 months of 2020 compared to 120 A320neo variants. The backlog of A320 family was still over the 6,000 mark and the total orders reached 15,572, whilst Boeing 737's was down to 14,861 aircraft.

| Type | Orders | Deliveries | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Backlog | Total | 2020 | 2019 | 2018 | 2017 | 2016 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A318 | 80 | - | 80 | - | - | - | - | 1 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A319 | 1,486 | 6 | 1,480 | 1 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 4 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A320 | 4,770 | 20 | 4,750 | 1 | 49 | 133 | 184 | 251 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A321 | 1,791 | 34 | 1,757 | 4 | 38 | 99 | 183 | 222 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| -- A320ceo -- | 8,127 | 60 | 8,067 | 6 | 91 | 240 | 377 | 477 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A319neo | 84 | 82 | 2 | - | 2 | - | - | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A320neo | 3,948 | 2,975 | 973 | 79 | 381 | 284 | 161 | 68 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| A321neo | 3,413 | 3,082 | 331 | 41 | 168 | 102 | 20 | - | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| -- A320neo -- | 7,445 | 6,139 | 1,306 | 120 | 551 | 386 | 181 | 68 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| (A320 family) | (15,572) | (6,199) | (9,373) | (126) | (642) | (626) | (558) | (545) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Type | Deliveries | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | 2014 | 2013 | 2012 | 2011 | 2010 | 2009 | 2008 | 2007 | 2006 | 2005 | 2004 | 2003 | 2002 | 2001 | 2000 | 1999 | 1998 | 1997 | 1996 | 1995 | 1994 | 1993 | 1992 | 1991 | 1990 | 1989 | 1988 | |

| A318 | - | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 6 | 13 | - | 17 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 9 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| A319 | 24 | 34 | 38 | 38 | 47 | 51 | 88 | 98 | 105 | 137 | 142 | 87 | 72 | 85 | 89 | 112 | 88 | 53 | 47 | 18 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| A320 | 282 | 306 | 352 | 332 | 306 | 297 | 221 | 209 | 194 | 164 | 121 | 101 | 119 | 116 | 119 | 101 | 101 | 80 | 58 | 38 | 34 | 48 | 71 | 111 | 119 | 58 | 58 | 16 |

| A321 | 184 | 150 | 102 | 83 | 66 | 51 | 87 | 66 | 51 | 30 | 17 | 35 | 33 | 35 | 49 | 28 | 33 | 35 | 22 | 16 | 22 | 16 | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| -- A320ceo -- | 491 | 490 | 493 | 455 | 421 | 401 | 402 | 386 | 367 | 339 | 289 | 233 | 233 | 236 | 257 | 241 | 222 | 168 | 127 | 72 | 56 | 64 | 71 | 111 | 119 | 58 | 58 | 16 |

| -- A320neo -- | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| (A320 family) | (491) | (490) | (493) | (455) | (421) | (401) | (402) | (386) | (367) | (339) | (289) | (233) | (233) | (236) | (257) | (241) | (222) | (168) | (127) | (72) | (56) | (64) | (71) | (111) | (119) | (58) | (58) | (16) |

Accidents and incidents

For the entire A320 family, 159 major aviation accidents and incidents have occurred,[99] including 47 hull loss accidents (latest one being Pakistan International Airlines Flight 8303 on 22 May 2020),[100] and a total of 1393 fatalities.[101]

On 26 June 1988, Air France Flight 296 crashed into trees at the end of runway at Mulhouse-Habsheim Airport, three out of 130 passengers were killed.[102] In February 1990 another A320, Indian Airlines Flight 605, crash landed short of the airport runway in Bangalore, the ensuing fire contributed to the casualty count of 92 of 146 on board.[103] The press and media later questioned the fly-by-wire flight control system, but subsequent investigations by commission of inquiry found "no malfunction of the aircraft or its equipment which could have contributed towards a reduction in safety or an increase in the crew's workload during the final flight phase ... the response of the engines was normal and in compliance with certification requirement."[26]

It has seen 50 incidents where several flight displays were lost.[104] Through 2015, the Airbus A320 family has experienced 0.12 fatal hull-loss accidents for every million takeoffs and 0.26 total hull-loss accidents for every million takeoffs.[105]

Specifications

| Subtype | A318[35] | A319[32] | A320[28] | A321[29] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cockpit crew | Two | ||||

| Exit limit EASA[85]/FAA[106] | 136 | 160 | 195/190 | 230 | |

| 1-class max. seating[107] | 132 at 29–30 in (74–76 cm) pitch | 156 at 28–30 in (71–76 cm) pitch | 186 at 29 in (74 cm) pitch[108] | 236 at 28 in (71 cm) pitch[109] | |

| 1-class, typical[107] | 117 at 32 in (81 cm) pitch | 134 at 32 in (81 cm) pitch | 164 at 32 in (81 cm) pitch | 199 at 32 in (81 cm) pitch | |

| 2-class, typical[107] | 107 (8F @ 38 in, 99Y @ 32 in) | 124 (8F @ 38 in, 116Y @ 32 in) | 150 (12F @ 36 in, 138Y @ 32 in) | 185 (16F @ 36 in, 169Y @ 32 in) | |

| Cargo volume | 21.20 m3 (749 cu ft) | 27.70 m3 (978 cu ft) | 37.40 m3 (1,321 cu ft) | 51.70 m3 (1,826 cu ft) | |

| Unit load devices | 4× LD3-45 | 7× LD3-45 | 10× LD3-45 | ||

| Length | 31.44 m (103 ft 2 in) | 33.84 m (111 ft 0 in) | 37.57 m (123 ft 3 in) | 44.51 m (146 ft 0 in) | |

| Wingspan | 34.10 m (111 ft 11 in) | 35.8 m (117 ft 5 in) [lower-alpha 3] | |||

| Wing area[27] | 124 m2 (1,330 sq ft), 10.3 aspect ratio | 128 m2 (1,380 sq ft), 10 AR | |||

| Wingsweep | 25 degrees[110] | ||||

| Height | 12.56 m (41 ft 2 in) | 11.76 m (38 ft 7 in) | |||

| Fuselage | 4.14 m (13 ft 7 in) height, 3.95 m (13 ft 0 in) width, 3.70 m (12 ft 2 in) cabin width | ||||

| MTOW | 68 t (150,000 lb) | 75.5 t (166,000 lb) | 78 t (172,000 lb) | 93.5 t (206,000 lb) | |

| Max. payload | 15 t (33,000 lb) | 17.7 t (39,000 lb) | 19.9 t (44,000 lb) | 25.3 t (56,000 lb) | |

| Fuel capacity | 24,210 L 6,400 US gal |

24,210–30,190 L 6,400–7,980 US gal |

24,210–27,200 L 6,400–7,190 US gal |

24,050–30,030 L 6,350–7,930 US gal | |

| OEW[107] | 39.5 t (87,100 lb) | 40.8 t (89,900 lb) | 42.6 t (93,900 lb) | 48.5 t (107,000 lb) | |

| Minimum Weight[85] | 34.5 t (76,000 lb) | 35.4 t (78,000 lb) | 37.23 t (82,100 lb) | 47.5 t (105,000 lb) | |

| Speed | Cruise: Mach 0.78 (447 kn; 829 km/h),[111] MMO: Mach 0.82 (470 kn; 871 km/h)[111] | ||||

| Range[lower-alpha 4] | 5,741 km (3,100 nmi) | 6,945 km (3,750 nmi)[lower-alpha 3] | 6,112 km (3,300 nmi)[lower-alpha 3] | 5,926 km (3,200 nmi)[lower-alpha 3] | |

| Takeoff (MTOW, SL, ISA) | 1,780 m (5,840 ft)[112] | 1,850 m (6,070 ft)[113] | 2,100 m (6,900 ft)[114] | ||

| Landing (MLW, SL, ISA) | 1,230 m (4,040 ft)[112] | 1,360 m (4,460 ft)[113] | 1,500 m (4,900 ft)[114] | ||

| Ceiling | 39,100–41,000 ft (11,900–12,500 m)[85] | ||||

| Engines (×2) | CFM International CFM56-5B, 68.3 in (1.73 m) fan | ||||

| PW6000A, 56.5 in (1.44 m) fan | IAE V2500A5, 63.5 in (1.61 m) fan | ||||

| Thrust (×2) | 96–106 kN (22,000–24,000 lbf) | 98–120 kN (22,000–27,000 lbf) | 133–147 kN (30,000–33,000 lbf) | ||

| ICAO code[115] | A318 | A319 | A320 | A321 | |

Engines

| Aircraft model | Certification date | Engines[85] |

|---|---|---|

| A318-111 | 23 May 2003 | CFM56-5B8/P |

| A318-112 | 23 May 2003 | CFM56-5B9/P |

| A318-121 | 21 December 2005 | PW6122A |

| A318-122 | 21 December 2005 | PW6124A |

| A319-111 | 10 April 1996 | CFM56-5B5 or 5B5/P |

| A319-112 | 10 April 1996 | CFM56-5B6 or 5B6/P or 5B6/2P |

| A319-113 | 31 May 1996 | CFM56-5A4 or 5A4/F |

| A319-114 | 31 May 1996 | CFM56-5A5 or 5A5/F |

| A319-115 | 30 July 1999 | CFM56-5B7 or 5B7/P |

| A319-131 | 18 December 1996 | IAE Model V2522-A5 |

| A319-132 | 18 December 1996 | IAE Model V2524-A5 |

| A319-133 | 30 July 1999 | IAE Model V2527M-A5 |

| A320-111 | 26 February 1988 | CFM56-5A1 or 5A1/F |

| A320-211 | 8 November 1988 | CFM56-5A1 or 5A1/F |

| A320-212 | 20 November 1990 | CFM56-5A3 |

| A320-214 | 10 March 1995 | CFM56-5B4 or 5B4/P or 5B4/2P |

| A320-215 | 22 June 2006 | CFM56-5B5 |

| A320-216 | 14 June 2006 | CFM56-5B6 |

| A320-231 | 20 April 1989 | IAE Model V2500-A1 |

| A320-232 | 28 September 1993 | IAE Model V2527-A5 |

| A320-233 | 12 June 1996 | IAE Model V2527E-A5 |

| A321-111 | 27 May 1995 | CFM56-5B1 or 5B1/P or 5B1/2P |

| A321-112 | 15 February 1995 | CFM56-5B2 or 5B2/P |

| A321-131 | 17 December 1993 | IAE Model V2530-A5 |

| A321-211 | 20 March 1997 | CFM56-5B3 or 5B3/P or 5B3/2P |

| A321-212 | 31 August 2001 | CFM56-5B1 or 5B1/P or 5B1/2P |

| A321-213 | 31 August 2001 | CFM56-5B2 or 5B2/P |

| A321-231 | 20 March 1997 | IAE Model V2533-A5 |

| A321-232 | 31 August 2001 | IAE Model V2530-A5 |

See also

Related development

Aircraft of comparable role, configuration and era

- Boeing 717

- Boeing 737 Classic

- Boeing 737 Next Generation

- Boeing 757

- Airbus A220

- Comac C919

- Embraer 195

- Irkut MC-21

- McDonnell Douglas MD-80

- McDonnell Douglas MD-90

- Tupolev Tu-204

Related lists

Notes

- Final assembly in France (Toulouse,) Germany (Hamburg), China (Tianjin,) and the United States (Mobile, Alabama)

- At 30 September 2017, Airbus still list American Airlines and US Airways as separate operators. Following a merger[2] of the airlines in October 2015, the American Airlines total used here is combined for both carriers

- with sharklets

- typical passengers and bags

References

- David Learmount (3 September 1988). "A320 in service: an ordinary aeroplane". Flight International. Vol. 134 no. 4129. Reed Business Publishing. pp. 132, 133. ISSN 0015-3710. Archived from the original on 29 November 2014. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- "US Airways' final flight closes curtain on another major airline". USA Today. 16 October 2015. Archived from the original on 21 October 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- "Airbus Orders and Deliveries". Airbus. 30 April 2020. Archived from the original (xls) on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "A320 has repaid faith of Airbus – and governments". Flightglobal. 29 March 2018.

- Pierre Muller (Fondation nationale des sciences politiques / Centre des recherches administratives) (1989). "La transformation des modes d'action de l'État à travers l'histoire du programme Airbus". Politique et Management Public (in French): 268.

- "AIRBUS AIRCRAFT 2018 AVERAGE LIST PRICES* (USD millions)" (PDF). airbus.com. Airbus. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 January 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2018.

- Wensveen, J.G. (1 January 2007). Air Transportation: A Management Perspective. Burlington, Vermont: Ashgate Publishing, 2007. p. 63. ISBN 978-0-7546-7171-8.

- Gunston, Bill (2009). Airbus: The Complete Story. Sparkford, Yeovil, Somerset, UK: Haynes Publishing. p. 213–216, 222–223. ISBN 978-1-84425-585-6.

- Norris, Guy and Mark Wagner (2001). Airbus A340 and A330. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing. p. 18. ISBN 978-0-7603-0889-9.

- "A320 family". Flight International. 1997. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 17 February 2011.

- Norris, Guy and Mark Wagner (1999). Airbus. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing. pp. 38, 41–44, 50–55, 87–88. ISBN 978-0-7603-0677-2.

- "Hawker Siddeley Trident". Century of Flight. Archived from the original on 11 September 2009. Retrieved 7 January 2010.

- Eden, Paul E. (15 December 2016). The world's most powerful civilian aircraft. New York. ISBN 9781499465884. OCLC 959698377.

- Payne, Richard (2004). Stuck on the Drawing Board: Unbuilt British Commercial Aircraft Since 1945. London, UK: The History Press Ltd. ISBN 978-0-7524-3172-7.

- Aris, Stephen (2002). Close to the Sun. London, UK: Aurum Press Ltd. p. 119–126. ISBN 978-1-85410-830-2.

- Eden, Paul E. (general editor) (2008). Civil Aircraft Today. London: Amber Books, 2008. p. 23–27. ISBN 978-1-905704-86-6.

- "A320 launch and first delivery of A300-600" (Press release). Airbus. 2 March 1984. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017.

- Guy Norris and Mark Wagner (1999). Airbus. MBI Publishing Company. ISBN 9781610606967.

- "Air France: launch customer of the A320" (Press release). Airbus. 10 June 1981. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017.

- "More than 80 orders for the planned A320" (Press release). Airbus. 1 October 1983. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017.

- "V2500" (PDF). International Aero Engines. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 July 2011. Retrieved 18 February 2011.

- "Engine Data File". Civil jet aircraft design. Elsevier. 2001. Archived from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- "A320 roll-out and first flight" (Press release). Airbus. 22 February 1987. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017.

- "A320 first delivery" (Press release). Airbus. 28 March 1988. Archived from the original on 22 February 2017.

- Laming, Tim and Robert Hewson (2000). Airbus A320. Zenith Imprint. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-7603-0902-5.

- Reed, Arthur (1992). Airbus: Europe's High Flyer. Zürich, Switzerland: Norden Publishing House. p. 84. ISBN 978-3-907150-10-8.

- Julian Moxon (17 March 1993). "A321: Taking on the 757". Flight International. Archived from the original on 24 March 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

- "A320 Dimensions & key data". Airbus. Archived from the original on 24 January 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- "A321 Dimensions & key data". Airbus. Archived from the original on 24 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- Sebdon, Gilbert (7 February 1990). "A321 victory for West Germany". Flight International. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 24 February 2011.

- Moxon, Henley (30 August 1995). "Meeting demands". Flight International. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 25 February 2011.

- "A319 Dimensions & key data". Airbus. Archived from the original on 15 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- Henley, Peter. "A319 flight test". Flight International. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- Paul Lewis (5 November 1997). "Time out in asia". Flight International. 152 (4599): 38,39. ISSN 0015-3710. Archived from the original on 22 June 2012. Retrieved 26 February 2011.

- "A318 Dimensions & key data". Airbus. Archived from the original on 26 February 2012. Retrieved 13 February 2012.

- "Flights that made Airbus' history". Airbus. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- Kingsley-Jones, Max (10–16 June 2003). "The Minibus Arrives". Flight International. Archived from the original on 27 February 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- "How Is An Aircraft Built > Final Assembly And Tests". Airbus. Archived from the original on 19 January 2019. Retrieved 17 January 2019.

- Joe Anselmo (2 March 2015). "Analysts Flag Potential Airliner Glut". Aviation Week & Space Technology. Archived from the original on 4 March 2015. Retrieved 4 March 2015.

- "Tianjin becomes eastern cousin of Toulouse". FlightGlobal. 23 February 2017. Archived from the original on 25 February 2017. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- "Airbus inaugurates Hamburg's fourth A320 Family production line" (Press release). Airbus. 14 June 2018. Archived from the original on 17 June 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2018.

- Norris, Guy (17 January 2019). "Airbus A320, A220 Evolution Considered As Mobile Expands". Aviation Week Network.

- "Airbus inaugurates new A320 structure assembly line in Hamburg". Airbus (Press release). 1 October 2019.

- Kaminski-Morrow, David (17 September 2019). "A320 family embarks on approach to 10,000 deliveries". Flightglobal.com.

- "Pictures: Airbus aims to thwart Boeing's narrowbody plans with upgraded 'A320 Enhanced'". Flight International. 20 June 2006. Archived from the original on 29 December 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "Skybus Becomes First North American Operator of Advanced CFM56-5B Tech insertion Engine". GE Aviation. 3 December 2007. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "A320 completes first IAE V2500 SelectOne". Flight International. 27 February 2008. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "Projects and Results : Aircraft wing advanced technology operations". CORDIS. European Commission. 13 June 2006. Archived from the original on 17 November 2017. Retrieved 16 November 2017.

- Max Kingsley-Jones (10 October 2006). "Airbus rethinks plan to put winglets on A320". Flight International. Archived from the original on 17 February 2015. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "Airbus undertakes Blended-Winglet evaluation on A320". Airbus. 17 December 2008. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- Max Kingsley-Jones (15 November 2009). "Dubai 09: A320s sharklets to deliver 3.5% lower fuel burn from 2012". Flight International. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- John Irish (15 November 2009). "Airbus says wingtip change to save fuel". Reuters. Archived from the original on 19 June 2012. Retrieved 22 February 2011.

- "Korean Air Aerospace to manufacture and distribute Sharklets" (Press release). Airbus. 31 May 2010. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 18 February 2013.

- Kaminski-Morrow, David (14 December 2011). "Airbus lawsuit details sharklet patent abuse". Flightglobal. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "AirAsia becomes first operator of Airbus' Sharklet equipped A320" (Press release). Airbus. 21 December 2012. Archived from the original on 1 March 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "Airbus drives cabin efficiency at Aircraft Interiors Expo" (Press release). Airbus. 30 March 2009. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "On board well-being". Airbus. Archived from the original on 20 November 2016. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- "Condor launch the A320 Enhanced Cabin Retrofit programme" (Press release). Airbus. 17 June 2009. Archived from the original on 18 June 2018. Retrieved 18 June 2018.

- cesar soto (12 September 2007). Enhanced Fap—Airbus 320. Youtube. Archived from the original on 13 April 2016. Retrieved 27 November 2016.

- Graham Warwick (30 August 1986). "A320: fly-by-wire airliner". Flight International.

- Anja Kollmuss & Jessica Lane (May 2008). "Carbon Offset Calculators for Air Travel" (PDF). Stockholm Environment Institute. Archived from the original (PDF) on 31 December 2010. Retrieved 26 November 2018.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "A320 Family / Technology". Airbus. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 3 January 2017.

- Charlotte Adams (1 January 2003). "Product Focus: Cockpit Displays: LCDs vs. CRTs". Avionics magazine. Archived from the original on 19 March 2017. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- "Airbus launches a new systems Enhancement Package for In-Service A320 Family aircraft" (Press release). Airbus. 24 September 2007. Archived from the original on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- "Digital head-up display system" (PDF). Thales. 2012. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- "Airbus's fly-by-wire pioneer Bernard Ziegler wins Flightglobal Lifetime Achievement Award". Flight Daily News. 11 July 2012. Archived from the original on 16 October 2015. Retrieved 9 July 2013.

- David Learmount (20 February 2017). "How A320 changed the world for commercial pilots". Flight International. Archived from the original on 21 February 2017. Retrieved 20 February 2017.

- Dominique Brière, Pascal Traverse - Aérospatiale (22–24 June 1993). "Airbus A320/A330/A340 Electrical Flight Controls: A Family of Fault-Tolerant Systems" (PDF). FTCS-23 the Twenty-Third International Symposium on Fault-Tolerant Computing. IEEE. 4.2 "Failure detection and redundancy". doi:10.1109/FTCS.1993.627364. ISBN 0-8186-3680-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 March 2009.

- Gilbert Sedbon (13 February 1988). "Keeping the Complex Simple". Flight International. p. 44. Archived from the original on 20 May 2012. Retrieved 5 November 2009.

- "P&W Main Website". Archived from the original on 9 June 2012.

- Aviation Week & Space Technology, 29 October 2007, p. 63

- Maynard, Micheline (14 July 2008). "A New Bombardier Jet Draws Only Tepid Demand". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 June 2011. Retrieved 4 April 2010.

- "Boeing Orders & Deliveries". Boeing.com. Boeing Press Calculations. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- "Orders and Deliveries search page". Boeing. 30 September 2017. Archived from the original on 31 August 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- "737 Model Summary". Boeing. 30 September 2017. Archived from the original on 27 September 2018. Retrieved 7 October 2017.

- "Historical Orders and Deliveries 1974–2009". Airbus S.A.S. January 2010. Archived from the original (Microsoft Excel) on 23 December 2010. Retrieved 10 December 2012.

- "Historical Deliveries". Boeing. December 2015. Retrieved 5 February 2016.

- Alex Derber (29 August 2018). "How The A320 Overtook The 737, And MRO Implications". Aviation Week Network. Archived from the original on 7 September 2018. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Norris, Guy (7 February 2006). "The 737 Story: Smoke and mirrors obscure 737 and Airbus A320 replacement studies". Flight International. Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 27 January 2014.

- "A30X Isn't Coming Soon". Aviation Week and Space Technology. Vol. 167 no. 18. 5 November 2007. p. 20. Archived from the original on 12 June 2017. Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- "Airbus sees lifespan of at least 10 years for re-engined A320". Flight International. 14 January 2010. Archived from the original on 11 March 2016. Retrieved 4 September 2018.

- Airbus A320 Family approved for 180 minute ETOPS by the FAA Archived 7 April 2016 at the Wayback Machine Airbus

- "The Airbus A320 family vs the Boeing 737 family: Who's got the muscle?". The Flying Engineer. 30 May 2010. Archived from the original on 23 March 2017. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

- Aircraft Value News (21 January 2019). "Prices of New A320s Hardly Changed in 20 Years". Archived from the original on 21 January 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "Type certificate data sheet No. EASA.A.064 for AIRBUS A318 – A319 – A320 – A321" (PDF). European Aviation Safety Agency. 29 November 2019.

- Wayne, Leslie (10 May 2007). "The Real Owner of All Those Planes". The New York Times. p. 2. Archived from the original on 15 May 2013. Retrieved 4 March 2011.

- Aircraft Value News (21 January 2019). "Values of A319 Continue to Taper Down". Archived from the original on 22 January 2019. Retrieved 21 January 2019.

- "Aircraft Families – Airbus Executive and Private Aviation – ACJ Family". Stagev4.airbus.com. Archived from the original on 29 May 2007. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- ACJ Specifications Archived 8 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine , airbus.com

- "ACJ Analysis" Business & Commercial Aviation Magazine – July 2002, Page 44

- "– Government of Armenia A319CJ". Airliners.net. 11 April 2010. Archived from the original on 24 October 2013. Retrieved 9 July 2012.

- "Il portale dell'Aeronautica Militare – Airbus A319CJ". Archived from the original on 10 January 2015. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

- "Strong demand for used Airbus A320 aircraft drives joint decision to stop freighter conversion programme" (Press release). Airbus. 12 April 2016.

- "ST Aerospace, Airbus and EFW to launch A320 and A321P2F conversion programme" (Press release). ST Aerospace. 17 June 2015.

- Ellis Taylor (12 August 2019). "Qantas to be launch operator for A321P2F". Flightglobal.

- David Kaminski-Morrow (25 February 2020). "A321 converted freighter secures EASA certification". Flightglobal.

- "Airbus steals the Paris air show". Hellocompany.org. 19 June 2007. Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 26 June 2011.

- David Kaminski-Morrow (15 November 2019). "A320's order total overtakes 737's as Max crisis persists". Flightglobal.

- "hull-loss and repairable damage occurrences". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. 20 May 2020.

- "hull-loss occurrences". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. 20 May 2020.

- "Airbus A320 Statistics". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. 22 May 2020.

- "AF296Q Accident description". Aviation Safety Network. Flight Safety Foundation. Archived from the original on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved on 19 February 2011.

- "Safety Recommendation A08-53" (PDF). National Transportation Safety Board. 22 July 2008. p. 2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 February 2017. Retrieved 23 March 2017.

According to Airbus, as of May 2007, 49 events similar to the United Airlines flight 731 and UK events had occurred in which the failure of electrical busses resulted in the loss of flight displays and various aircraft systems.

- "Statistical Summary of Commercial Jet Airplane Accidents" (PDF). Boeing. July 2016. p. 19. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 November 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2015.

- "Type Certificate Data Sheet" (PDF). FAA. 12 August 2016. Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 December 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- "All About the Airbus A320 Family". Airbus. 2009. Archived from the original on 11 September 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- "High-density A320s for easyJet will retain seat pitch, assures airline". Runway Girl Network. 1 March 2016. Archived from the original on 14 September 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- "Airbus Studies 236-Seat A321". Aviation Week. 10 December 2012. Archived from the original on 16 September 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- "Airbus Aircraft Data File". Civil Jet Aircraft Design. Elsevier. July 1999. Archived from the original on 27 January 2017. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- "A320 Family Technology". Airbus. Archived from the original on 3 April 2016. Retrieved 1 September 2016.

- "ACJ318". Airbus. Archived from the original on 1 December 2016.

- "ACJ319". Airbus. Archived from the original on 5 January 2013.

- "ACJ320". Airbus. Archived from the original on 6 December 2016.

- "Document 8643". International Civil Aviation Organization.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Airbus A320 family. |

- Official Airbus website of the A320 aircraft family

- Max Kingsley-Jones (26 March 2018). "Analysis : Three decades since first A320 delivery". Flightglobal.

.jpg)