Gay icon

A gay icon is a public figure who is highly regarded and beloved by the LGBT community. A gay icon can either be a part of the LGBT community or heterosexual, but heterosexual gay icons are often highly supportive of their fans within the community and the rights of LGBT people. Organizations such as GLAAD routinely recognize public figures for their contributions and support for the LGBT community. Gay icons exist across cultures, most prominently in North and South America, Europe, and Asia.

Many gay icons are celebrities in the entertainment industry, but can also include figures in politics, history, sports, literature, and other mediums. Prominent entertainers considered to be gay icons often incorporate themes of acceptance, self-love, and sexuality in their work. Gay icons of all orientations have acknowledged the role that their gay fans have played in their success, including Bette Midler, Cher, Diana Ross, Madonna, Mariah Carey, Beyoncé, and Lady Gaga. Politicians considered to be gay icons typically attain their status in the LGBT community for consistently supporting and advocating for LGBT rights.

Historical

The earliest gay icon may have been Saint Sebastian,[1] a Christian saint and martyr, whose combination of strong and shirtless physique, symbolic arrow-pierced flesh and rapturous look of pain have intrigued artists, both gay and straight, for centuries and began the first explicitly gay cult in the nineteenth century.[1] Journalist Richard A. Kaye wrote, "Contemporary gay men have seen in Sebastian at once a stunning advertisement for homosexual desire (indeed, a homoerotic ideal), and a prototypical portrait of a tortured closet case."[2]

Due to Saint Sebastian's status as a gay icon, Tennessee Williams chose to use the saint's name for the martyred character Sebastian in his play, Suddenly, Last Summer.[3] The name was also used by Oscar Wilde—as Sebastian Melmoth—when in exile after his release from prison. Wilde, an Irish writer and poet, was about as "out of the closet" as was possible for the late 19th century, and is himself considered to be a gay icon.[4]

Marie Antoinette was an early lesbian icon. Rumors about her relationships with women circulated in pornographic detail by anti-royalist pamphlets before the French Revolution. In Victorian England, biographers who idealized the Ancien Régime made a point of denying the rumours, but at the same time romanticised Marie Antoinette's "sisterly" friendship with the Princesse de Lamballe as—in the words of an 1858 biography—one of the "rare and great loves that Providence unites in death."[5] By the end of the 19th century, she was a cult icon of "sapphism." Her execution, seen as tragic martyrdom, may have added to her appeal.

Allusions to her appearance were made in early 20th century lesbian literature—most notably Radclyffe Hall's The Well of Loneliness—where the gay playwright Jonathan Brockett describes Marie Antoinette and de Lamballe as "poor souls... sick to death of the subterfuge and pretenses."[6] She had crossover appeal as a gay icon, as well, at least for French novelist, playwright, poet, essayist, and political activist Jean Genet, who was fascinated by her story. He included a reenactment of her execution in his 1947 play The Maids.[5]

Modern

Modern gay icons in entertainment include film stars and musicians, most of whom have strong, distinctive personalities, and many of whom died young or under tragic circumstances. For example, Greek-American opera singer Maria Callas—who reached her peak in the 1950s—became a gay icon because the uniquely compelling qualities of her stage performances were allied to a tempestuous private life, a sequence of unhappy love affairs, and a lonely premature death in Paris after her voice had deserted her.

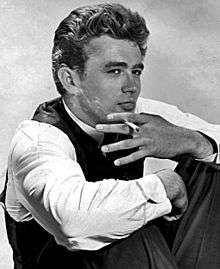

Lesbian icons, sometimes called "dykons" (a portmanteau of the words "dyke" and "icon") are most often powerful women who are, or are rumored to be, lesbian or bisexual.[7][8] However, a few male entertainers have also had iconic status for lesbian people. James Dean was an early lesbian icon who, along with Marlon Brando, influenced the butch look and self-image in the 1950s and after.[9][10][11][12] One critic has argued for Johnny Cash as a minor lesbian icon, attributing his appeal to "lesbian identification with troubled and suffering masculinity."[13]

Gay icons may be homosexual or heterosexual, out or in the closet, male or female. The women most commonly portrayed by drag queens are usually gay icons. The definition of what it means to be a "gay icon" has come under criticism in recent years for a lack of substance. Paul Flynn of The Guardian wrote, "The concept of gay icon is a cheap ticket...[and] the idea of gay iconography itself is currently replaceable with the idea of popularity and the ability to carry a strong, identifiable, signature look."[14] Author Michael Thomas Ford depicts a similar attitude in his work of fiction Last Summer.

Non-American cultures

.jpg)

Although the term "gay icon" is most commonly used in the United States, the concept is found in other cultures, as well. Dalida, a French singer of Italian origin who was born in Egypt had a career-long gay following that extended out of Paris and well into the Middle East. In the years since her death in 1987, her iconic status has not diminished.[15][16]

Asian

India’s first openly queer Stand-Up Comedian Navin Noronha,[17] Indian actor Anil Kapoor [18] and actress Sonam Kapoor,[19] Taiwanese singer Jolin Tsai,[20] Hong Kong singer Leslie Cheung,[21] South Korean pop group Girls' Generation,[22] chinese Ren Hang (photographer) and Thai singer Christina Aguilar[23] have been called gay icons. Singers like Ayumi Hamasaki, Namie Amuro, and Utada Hikaru have been considered gay icons of Japanese pop.

European

In the Netherlands, Dutch singer and actress Willeke Alberti is widely embraced as a gay icon, due to a combination of her song repertoire, her durability, and her performances in support of manifold gay causes.[24] Spanish actress Carmen Maura, Spanish politician Pedro Zerolo,[25] Italian singers Mina and Raffaella Carrà, Scottish pop singer Jimmy Somerville, German actress and singer Hildegard Knef, and English singers Dusty Springfield and Sophie Ellis-Bextor are also considered gay icons,[26][27][28][29][30][31] as are French entertainers Dalida, Mylène Farmer, Lorie, Jenifer, Alizée, and Ysa Ferrer, Ukrainian boy band Kazaky, Turkish singer Ajda Pekkan, and Italian actress Isabella Rossellini.[32][33][34][35]

Latin America

Latin American figures have also gained reputations as gay icons. Pop band Alaska y Dinarama is one example. Their single "¿A quién le importa?" ("Who Cares?"), which was later covered in 2002 by Thalía, was a hit for the 1980s Spanish band, becoming a gay anthem for the Hispanophone LGBT community. Singer Gloria Trevi is considered a gay icon, especially after her release of "Todos me miran" ("Everyone's Looking at Me") featuring a rejected gay man turned drag queen, but had been popular with the gay and lesbian community in Mexico since the beginning of her career for being a controversial and powerful singer.[36] Mexican singer and actress Paulina Rubio has been a gay icon for Latin America after supporting gay marriage and publicly stating that she wants to have sex with fellow gay icon Madonna.[37]

Other modern Latin American gay icons include singers Alaska, Ricky Martin, Selena, La Lupe, Sara Montiel, Lola Flores and Chavela Vargas.[38][39]

Argentine gay icons include actresses Isabel Sarli, Susana Giménez and Moria Casán, the trans woman Florencia de la V, First Lady Eva Perón and President Cristina Fernández de Kirchner.[40]

Venezuelan actresses Mimi Lazo, Haydée Balza, Lila Morillo, Mirtha Perez, Kiara and Hilda Abrahamz are the most beloved gay icons in the country, often impersonated by drag queens. Other artists who have fought for gay rights in the country are the model and actress Patricia Velásquez, the play writer Isaac Chocrón, the journalist Boris Izaguirre, the actors Edgar Ramírez and Luis Fernández as for the youtuber Pedro Figueira known as La Divaza.

In Brazil, pop singers Kelly Key, Sandy, Lorena Simpson, Preta Gil, and Wanessa are considered gay icons. In 2012, Key was honored with the "Pink Triangle Award," a Brazilian LGBT award, considered the "Gay Oscar".[41][42][43][44]

Entertainment

1930s–1940s

The 1930s saw a number of writers, political activists, and celebrities garner reputations as gay icons. Poet and satirical writer Dorothy Parker reportedly had a large gay following. Though the phrase "friend of Dorothy" was made popular in later years by Judy Garland's role in The Wizard Of Oz (1939), some speculate it originated with Parker.

Actress Bette Davis' performance in Dark Victory (1939), was dubbed by queer theorist Eve Sedgwick as "the epistemology of the closet."[45] Davis' portrayal of the melodramatic Judith Traherne made her talent for playing someone with a secret revered and her "camp-worthy" dialog reflexive of the "flamboyant gay queen of the dramatic arts."[45] Ed Sikov, author of Dark Victory: The Life of Bette Davis, wrote that 20th century gay men developed their own subculture following Davis' example.[45]

In Marcella Althaus-Reid's Liberation Theology and Sexuality, Marlene Dietrich, who is considered to be the first German-born actress to receive critical acclaim in Hollywood, is a model of liberation and subversion, as well as beauty, perfection and sensuality.[46][47] In Rio de Janeiro, Althaus-Reid discovered a statue of Dietrich dressed as Our Lady of Aparecida in a gay bar in Copacabana beach.[47] The image of Dietrich as the black Virgin Mary represents her overcoming duality.[47] According to Althaus-Reid, it is a figure that sanctifies Dietrich while simultaneously liberating Mary.[47]

Other icons from this time period include Mae West, Jean Harlow, Carol Channing,[48] Mona von Bismarck, Greta Garbo, Queen Astrid, Josephine Baker, Wallis Simpson, Katharine Hepburn and Cary Grant, who endured speculation over his alleged relationships with men.

1950s–1960s

An archetypal gay icon is Judy Garland.[49] Michael Bronski, author of Culture Clash: The Making of Gay Sensibility, describes Garland as "the quintessential pre-Stonewall gay icon."[50] So revered is she as a gay icon that her best known film role, Dorothy Gale in The Wizard of Oz, became used as code among homosexuals in the 1950s.[51]

The expression "Is he a friend of Dorothy?" was slang for "Is he gay?"[51] The character Dorothy meets an odd group of friends during her journey through Oz—the Tin Man, the Cowardly Lion and the Scarecrow—and so referring to an individual as a "friend of Dorothy" meant that they were "unusual or odd" and, therefore, "queer".[51] Though Garland has been noted for her embodiment of camp in her acting roles, Bronski argues that she was the "antithesis of camp" and "made a legend of her pain and oppression."[50] As Bronski observes, the bleak setting of 1950s Hollywood had replaced the "sauciness of the [1930s] and the independence of the [1940s]."[50] Garland, as well as Connie Francis, Lana Turner and Susan Hayward, epitomized the idea that "suffering was the price of glamor...[and] the women stars of the [1950s] reflected the condition of many gay men: they suffered, beautifully".[50]

Garland's daughter Liza Minnelli would later follow in her mother's footsteps as a gay icon, as would fellow musical artist Barbra Streisand.[8][40] Joan Crawford has been described as the "ultimate gay icon—the martyr who suffered for her art and, therefore, enabled herself to bond with this all-important faction of her fanbase."[52] In Joan Crawford: The Essential Biography, author Lawrence J. Quirk explains that Crawford appealed to gay men because they sympathized with her struggle for success, in both the entertainment industry and in her personal life.[53] Though Crawford had been a notable film star during the 1930s and 1940s, according to David Bret, author of Joan Crawford: Hollywood Martyr, it was not until her 1953 film Torch Song that she was seen as a "complete gay icon, primarily because it was shot in color." Bret explains that seeing the actress' red hair, dark eyes and "Victory Red" lips linked her to "gaydom's other sirens: Dietrich, Garland, Bankhead, Piaf, and new recruits Marilyn Monroe and Maria Callas."[52]

Actress Lucille Ball was also a prominent icon from this period. In Lee Tannen's book I Loved Lucy: My Friendship with Lucille Ball, the author describes his experience when he witnessed Lucille Ball being labeled a gay icon for the first time by a mutual friend.[54] Ball was told of the adoration she received from gay men, as a bar in West Hollywood was known for routinely playing episodes of her television series I Love Lucy every weekend.[54]

1970s

During the late 1970s, many female comedians appeared, joining the ranks of what had stereotypically been a male profession, including Joan Rivers, who began appearing on The Tonight Show Starring Johnny Carson. Rivers gained a strong gay following after performing in Greenwich Village, an LGBT friendly area of New York, from the early days of her career. Rivers' frank and sharp use of wit and insults (largely turned toward herself) made her an instant gay icon.

The first gay icon of the 1970s underground gay disco scene was the "Queen of Disco" Donna Summer, whose dance songs became anthems for the clubbing gay community, and her music the back beat to the battles of the gay rights movement of the 1970s.[55] Her number one single "Love to Love You Baby"—regarded as an "absolute disco epic"—not only became a gay anthem because of its "unabridged sexuality", but it also brought European-oriented disco to the United States and influenced the course the recording industry would take in the following years.[56] However, Summer became immersed in controversy when, after becoming a Born again Christian, and during a 1983–84 tour, at the dawn of the HIV/AIDS crisis, she was allegedly reported as making homophobic remarks; including that "AIDS was God's punishment to homosexuals." However, she later denied having ever made these comments.[57] Paul Flynn of The Guardian referred to Summer as "the accidental gay icon" as she did not make songs with the intention of appealing to LGBT people, but her songs nevertheless became popular in the community.[57] Fellow disco singer Gloria Gaynor was embraced by the gay community because of her single "I Will Survive", which served as an anthem for both feminists and the gay rights movement.[58] The Village People, a pioneering disco group, are also regarded as gay icons for bringing gay disco culture into the mainstream with their popular disco and dance hits; and their costumes, with each member of the group representing a part of gay erotica (a policeman, a sailor, a construction worker, a cowboy, a leather clad man).[59]

Actress Lynda Carter became a gay icon after starring as Wonder Woman in the 1975–1979 series of the same name. Her role as the heroine attracted the LGBT community for her onscreen persona of female strength and fashionable outfits.[60] Carter is a vocal supporter of LGBT equality and has participated in the New York City Gay Pride Parade.[61]

Singer Sylvester became a gay icon after releasing his Hi-NRG single "You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real)" in 1978. Sylvester often made appearances in drag, and often described as a disco diva because of his falsetto voice and flamboyant appearance. He also influenced the gay nightclub scene in the late seventies and eighties. Sylvester died of AIDS-related complications in 1988.[62]

Singer Cass Elliot became known as a gay icon, both during her solo career and as a member of The Mamas & the Papas. Her musical impact became known through her camp fashion and lyrics praising individuality (such as "Make Your Own Kind of Music" and "Different") and free love. Her music was later featured in the acclaimed gay film Beautiful Thing (1996), adapted from the play of the same name.

Singer and actress Bette Midler became recognized as a gay icon in the 1970s. After performing on Broadway, Midler began performing at the Continental Baths, a gay bathhouse in the city, where she became close to her piano accompanist Barry Manilow, who produced her first major album The Divine Miss M (1973). "Despite the way things turned out [with the AIDS crisis], I'm still proud of those days [singing at gay bathhouses]. I feel like I was at the forefront of the gay liberation movement, and I hope I did my part to help it move forward. So, I kind of wear the label of 'Bathhouse Betty' with pride," Midler reminisced in 1998.[63]

Freddie Mercury, the lead vocalist of Queen, was widely considered a gay icon,[64] with his LGBT fanbase growing by the 1980s. Although Freddie Mercury never revealed his sexuality publicly[65] (even when events made it seem inevitable[66]), he often "playfully alluded to his queerness with his flamboyant, high-camp stage antics", according to Gay Star News.[67] In 1992, John Marshall of Gay Times expressed the following opinion: "[Mercury] was a 'scene-queen,' not afraid to publicly express his gayness, but unwilling to analyse or justify his 'lifestyle' ... It was as if Freddie Mercury was saying to the world, 'I am what I am. So what?' And that in itself for some was a statement."[68] Many assumed him to be either gay or bisexual[69] and not sexually active.[70] He would often distance himself from his later partner, Jim Hutton, during public events.[71] On the evening of November 24, 1991, Mercury died at the age of 45 at his home in Kensington of AIDS-related illnesses (bronchial pneumonia).[72]

1980s

Artists particularly embraced by the gay community during the 1980s included Whitney Houston, Tina Turner, Patti Labelle, Alaska, Charo, Dolly Parton, Elaine Paige, Amanda Lear, Prince and Mylène Farmer.[32][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82] Several Britons were seen as gay icons, including singers Boy George, David Bowie, George Michael, Morrissey, Pet Shop Boys, Kate Bush, Annie Lennox, and writer Quentin Crisp.[40][82] Elton John also became a gay icon during this decade, a status strengthened throughout the years.[83][84][85][86] Diana Ross, a long time gay icon, of The Supremes; released the song "I'm Coming Out",[87] which brought an additional significance to the phrase of "coming out".

Cher became notable in the gay community not only for her music, but also her drag, her leather outfits of the 80s made her popular with the leather crowd.[88] In later years, her son Chaz Bono came out as gay at the age of 17 (and many years later as a transgender man), much to his mother's initial feelings of "guilt, fear and pain".[88] When Cher was able to accept her son's sexual orientation, she realized that Chaz, as well as other LGBT people, "didn't have the same rights as everyone else, [and she] thought that was unfair".[89] Cher emerged not only as an icon among LGBT people, but also as a role model for straight parents who have gay, lesbian, bisexual or transgender children.[88] She became the keynote speaker for the 1997 national Parents, Families and Friends of Lesbians and Gays (PFLAG) convention.[88][89] Cher's longevity in the music industry has often been credited to her gay following.[90] William J. Mann, author of Gay Pride: A Celebration of All Things Gay and Lesbian, comments "[w]e'll be dancing to a 90-year-old Cher when we're 60. Just watch".[90]

Continuing into the 1980s, pop music singer Madonna—dubbed the "Queen of Pop" and "Queen of Dance" by the media, and later the "World's Most Successful Female Recording Artist" by Guinness World Records—became the preeminent gay icon of the late 20th century.[91][92][93] The Advocate's Steve Gdula commented "[b]ack in the 1980s and even the early 1990s, the release of a new Madonna video or single was akin to a national holiday, at least among her gay fans."[93] Gdula also stated that during this period, concurrent with the rise of the AIDS epidemic, "when other artists tried to distance themselves from the very audience that helped their stars to rise, Madonna only turned the light back on her gay fans and made it burn all the brighter."[93]

Georges Claude Guilbert, author of Madonna As Postmodern Myth: How One Star's Self-Construction Rewrites Sex, Gender, Hollywood and the American Dream, writes that Madonna's reverence as a gay icon is equated with that of Judy Garland, noting similarities between the two popular culture icons.[94] Guilbert writes that gay icons "usually belong to one or the other of two types of female stars: either the very vulnerable or suicidal star, or the strong idol whom nobody or nothing resists, like Madonna."[94] According to Madonna: An Intimate Biography, the pop star has always been aware that her most loyal fans were gay men, has appeared in gay-oriented magazines as an activist for gay rights, and was even named in the book The Gay 100 as one of the most influential gay people in history.[95]

Other superstar recording artists, including Cyndi Lauper, followed.[96] Lauper and Madonna were seen as trailblazers of women's sexual liberation.[97] Lauper's debut album She's So Unusual (1983) generated a large following of fans responding to the "gay-friendly camp and lesbian-friendly womyn power epitomized in [her] femme anthem 'Girls Just Want to Have Fun'."[98] Lauper explained that growing up during the 1960s influenced her dedication to fair and equal treatment of all people, noting that the music of the 1960s "helped to open the world's point of view to change."[99] According to Lauper "It wasn't until my sister came out in the early [1970s] that I became more aware of the bigoted slurs and the violence against a community of people...who were gay."[99] Lauper has since become an active gay rights activist, often encouraging LGBT people and their allies to vote for equal rights.[99] Political activism for LGBT rights was the theme of Lauper's annual True Colors Tour.

.jpg)

In the mid- to late-1980s, Oprah Winfrey emerged as an icon for the gay community with an intimate confessional communication style that altered the cultural landscape. According to the book Freaks Talk Back by Yale sociologist Joshua Gamson, the tabloid talk show genre popularized by Oprah Winfrey and Phil Donahue, did more to make gay people mainstream and socially acceptable than any other development of the 20th century by providing decades of high-impact media visibility for sexual nonconformists.[100][101]

Fellow gay icon Ellen DeGeneres cast Winfrey to play the therapist she comes out of the closet to on the controversial episode of her Ellen sitcom. Though Winfrey abandoned her tabloid talk show format in the mid-1990s as the genre became flooded by more extreme clones like Ricki Lake, Jenny Jones and Jerry Springer, she continued to broadcast shows that were perceived as gay-friendly. Her show Oprah's Big Give was the first reality TV show with an openly gay host Nate Berkus. Her own show has been nominated several times for GLAAD Media Awards, and another in 2010 for an interview with Ellen DeGeneres and her wife Portia de Rossi,[102] winning one in 2007[103][104] Oprah Winfrey also co-produced the Oscar-winning film Precious (2009), which was honored by GLAAD for portraying a lesbian couple as heroines.[105]

Winfrey's iconic status among gay males has entered the popular culture. One of the stars of the reality TV show The Benefactor was a gay African American man named Kevin who was so obsessed with Winfrey that he would ask "What would Oprah do?" before making any strategic decision. Adam Lambert is another high-profile gay man who has described himself as a fan of Winfrey.[106] Other icons from this decade include Joan Collins, Tori Amos, Tina Arena, Harvey Fierstein, and Stevie Nicks.[8][83][107][108][109][110][111][112][113]

1990s

Janet Jackson, who twice was established as one of the highest-paid recording artists in the history of contemporary music during the 1990s, became a gay icon after she released her sixth studio album The Velvet Rope (1997).[114][115][116] The album was honored by the National Black Lesbian and Gay Leadership Forum and received the award for Outstanding Music Album at the 9th Annual GLAAD Media Awards in 1998 for its songs that dealt with sexual orientation and homophobia.[117] On April 26, 2008, she received the Vanguard Award—a media award from the Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation—to honor her work in the entertainment industry in promoting equality for LGBT people.[117] GLAAD President Neil G. Giuliano commented, "Ms. Jackson has a tremendous following inside the LGBT community and out, and having her stand with us against the defamation that LGBT people still face in our country is extremely significant."[117][118]

Deborah Cox quickly becomes a gay icon due to her investment for the fight against the AIDS but also and especially thanks to club remixes included in her singles, which are frequently played in the discothèques.[119][120][121]

Writer, composer and singer, Ysa Ferrer is regarded as the French "Kylie". Her dance/electro style, called "Pop Kosmic" is very popular in France and Russia especially in the gay community where she is considered as a true icon.[122][123]

Glenn Close was established as a gay icon after portraying Margarethe Cammermeyer in Serving in Silence (1995). She gained more recognition through her campy portrayal of the glamorous Cruella de Vil in 101 Dalmatians (1996) and as the fading diva Norma Desmond in the Broadway musical Sunset Boulevard.[124]

Garth Brooks, whose sister is openly lesbian, was one of the first non-LGBT male artists to openly back gay rights, and later same-sex marriage.[125]

The Spice Girls became gay icons during the 1990s,[126][127] on account of their dance-pop sound, flamboyant outfits, outgoing personalities and affirmations of equality. Geri Halliwell, in particular, went on to become a gay icon in her own right during her solo career in the 2000s, covering The Weather Girls' classic gay anthem, "It's Raining Men".[128][129] In 2016, Halliwell received the Honorary Gay Award at the annual Attitude Awards.[130]

Mariah Carey who dominated the 90's with chart-topping hits is regarded as a gay icon. Her 1993 single "Hero" is regarded as an anthem for the gay community as it touches upon themes of embracing individuality and overcoming self-doubt.[131] Carey's diva persona has also given her much admiration from gay fans as she embraces and epitomizes glamour, confidence, and extravagance.[132] Carey was honored by GLAAD in 2016 with the "GLAAD Ally Award" for which she expressed gratitude to her LGBT+ fans. In her speech Carey thanked the community, "For the unconditional love because it's very difficult for me to have that. I haven't experienced much of it...I wish all of you love, peace, [and] harmony..."[133]

2000s

.jpg)

The main single of I Turn to You by Melanie C, which became a gay anthem, was released as the "Hex Hector Radio Mix", for which Hex Hector won the 2001 Grammy as Remixer of the Year.[134]

Following her "Ride It" single in 2004, which became a gay anthem, Geri Halliwell confirms her gay icon status.[129][135]

Kylie Minogue reinvented herself musically in the first decade of the 21st century and found herself faced with a renewed and increasing gay fanbase.[136][137] She said, "My gay audience has been with me from the beginning ... they kind of adopted me."[137] Minogue first became aware of her gay audience in 1988, when several drag queens performed to her music at a Sydney pub, and she later saw a similar show in Melbourne. Minogue felt "very touched" to have such an "appreciative crowd," and this encouraged her to perform at gay venues throughout the world, as well as headlining Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras. Her sister, Dannii Minogue, also has a large gay following and has been regarded a gay icon.[138]

Irish actress and television presenter Carrie Crowley, best known abroad for presenting the Eurovision Song Contest 1997, has also been cited as a gay icon.[139]

As a result of her role playing Karen Walker on Will & Grace, Megan Mullally emerged as a gay icon.[140] One commentator wrote that the show "won the actress an impressive gay following, both with men and women, who want to be her and with her."[140]

The television series Sex and the City was popular among gay men and spawned gay icons Sarah Jessica Parker and Kim Cattrall.[83][141]

Christina Aguilera is regarded a gay icon, a status that came following the release of the song "Beautiful", which became a gay anthem and was recognized as "the most empowering song for lesbian, gay and bisexual people of the decade."[142] The accompanying video featured people who can feel ostracised from society, including a same-sex couple and a transgender woman. Aguilera also was honored with the very first spot on The Abbey's Gay Walk of Fame for her contributions to gay culture, re-enforcing the title of gay icon she earned a decade ago with her anthem "Beautiful".[143][144][145]

2010s–present

Various LGBT celebrities have been embraced as gay icons after opening up about their sexual orientation and/or gender identity as media professionals and public figures, including Mj Rodriguez,[146] Indya Moore,[147] Dominique Jackson,[148] Angelica Ross,[149] Lily Tomlin,[150] Margaret Cho, Jobriath,[151] Divine (performer), John Waters, Stanley Kwan,[152] Manila Luzon,[153] Ricky Martin, Ryan Murphy, George Michael,[154] Elton John,[155] Eric Andre,[156] Lance Bass,[157] Ellen DeGeneres,[158] Portia de Rossi,[159] Jodie Foster, Hannah Gadsby,[147] Andreja Pejić,[159] Rupert Everett,[160] Neil Patrick Harris,[161] Janelle Monáe, Colton Haynes,[162] Zachary Quinto,[163] Matt Bomer,[164] Luke Evans,[165] Wentworth Miller,[166] Rosie O'Donnell,[158] Jeff Sheng,[153] Frank Ocean,[167] RuPaul,[168] George Takei,[169] Ian McKellen,[170] Christina Hendricks,[171] Sarah Paulson,[172] Laverne Cox,[173] Conchita Wurst,[174] Alexander Wang (designer),[153] Billy Porter,[175] Ruby Rose,[159] Troye Sivan,[174] Lil Nas X, Sab Shimono,[153] Jenny Shimizu,[153] Jason Wu,[153] Jaboukie Young-White,[176] John Yang (journalist),[153] Megan Ellison,[176] Mark Kanemura,[153] Lena Waithe,[176] Billy Eichner,[176] and Lizzo.

Ariana Grande has been named by Billboard the Gay Icon of this generation.[177][178] The same publication also praised Lady Gaga for earning her gay icon status and called her "one of the LGBTQ community's fiercest advocates".[179][158]

Popular musicians including Katy Perry,[180] Adam Lambert,[181] Dua Lipa,[182] Nancy Sinatra,[183] Gwen Stefani,[160] Hayley Kiyoko,[184] Lily Allen,[185] Lana Del Rey,[186] Taylor Swift,[187] Marina and the Diamonds,[188] P!nk,[189] Beyoncé,[158] Mariah Carey,[190] Christina Aguilera,[191] Miley Cyrus,[192]Kesha,[190] Jennifer Lopez,[193] Britney Spears,[190][194] Carly Rae Jepsen,[195] Charli XCX,[196] Halsey,[176] Nicki Minaj,[197] Li Yuchun,[198] St. Vincent[176] Kim Petras,[199] SOPHIE,[200] Björk,[201] Kylie Minogue,[202] Stevie Nicks,[203] Demi Lovato,[204]Idina Menzel,[205] Macklemore,[206] Robyn, Adele,[207] Kacey Musgraves,[208] and Cupcakke,[209][210] are notable gay icons of current times.

Melanie Brown was shown kissing another woman in her "For Once in My Life" video, making this song a hymn of the gay community.[211][212][213][214]

Public figures like supermodel Tyra Banks,[215][216] Matsuko Deluxe,[217] Troy Perry,[176] Helen Zia,[198] and Niki Nakayama[176] are considered gay icons.

Many famous actors and thespians have been celebrated as gay icons, including Jane Fonda,[218][219] Angela Lansbury,[220] Whoopi Goldberg,[221] Kathy Griffin,[222][223] Jessica Lange,[224] Angela Bassett, Kathy Bates, Carrie Fisher,[225] Tim Blake Nelson, Magda Szubanski,[226] Mitsu Dan,[217] Michelle Rodriguez,[176] Lucy Lawless,[227][228] Amanda Henderson,[229] Nicole Kidman, Mo'Nique,[230] Maggie Smith,[231][232] BD Wong,[233] Akihiro Miwa,[217] Kristin Chenoweth,[234] Leslie Grossman,[234] Amandla Stenberg,[176] Bai Ling,[233] Jin Xing,[198] Kristen Stewart,[176]Laura Dern,[235][236] and Patricia Clarkson[237].

Meryl Streep became a gay icon after portraying Miranda Priestly in the film The Devil Wears Prada.[238][239]

Emmy award winning comediennes Lisa Kudrow and Catherine O'Hara became popular amongst LGBTQ audiences following their roles of Valerie Cherish and Moira Rose in the sitcoms The Comeback and Schitt'$ Creek, respectively. [240] .[241][242][243]

Many heterosexual actors, including Timothée Chalamet,[244] Olivia Colman,[245] Taron Egerton,[246] Jake Gyllenhaal,[247][248] Heath Ledger,[247] Richard Madden,[249] Nick Robinson,[250] Chloë Sevigny [251] & Rachel Weisz[252] all developed a significant LGBTQ+ fanbase after portraying openly queer characters Elio Perlman, Anne, Queen of Great Britain, Sir Elton John, Jack Twist, Ennis Del Mar, John Reid, Simon Spier, Lana Tisdel and Baroness Abigail Masham, with many of them being dubbed "honorary gays".[253]

Sports

Ben Cohen, Balian Buschbaum, Amélie Mauresmo, Ian Roberts (rugby league),[226] Billie Jean King,[8][254][255] Tom Daley,[256] Robbie Rogers,[257] Michael Sam,[258] Brian Boitano,[259] Adam Rippon,[260] Gus Kenworthy,[260][261] Ian Thorpe,[262] and Gareth Thomas[263][264] are considered by some to be gay icons within the sports industry.

Politics

In the political arena, gay icons are represented by, among others, Diana, Princess of Wales,[266] Catherine, Duchess of Cambridge,[267] Manvendra Singh Gohil,[233] Sheila Kuehl,[176] Pedro Zerolo,[265] Justin Trudeau,[268] Angela Merkel,[268] Kim Coco Iwamoto,[233] Brian Sims,[269] Dianne Feinstein,[270] Alex Greenwich,[226] Mark Takano,[233] Cate McGregor,[226] George Moscone,[271] Pamela K. Chen[198] Coretta Scott King,[272] Abraham Lincoln,[273] Nelson Mandela,[206] Winnie Mandela,[274] Tony Blair,[170] Hillary Clinton,[275] Eva Perón,[276] Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis,[277] and Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir, the first openly lesbian head of government of the modern era.[278][279] Roger Casement, an Irish civil rights activist, became a gay icon of the early 20th century.[280] Civil rights activist Coretta Scott King was held in high regard among members of the gay community for her involvement in the Gay Rights Movement.[272] During her lifetime, she routinely equated the goals of the Civil Rights Movement, led by her late husband Martin Luther King Jr., with that of LGBT activism.[272]

I still hear people say that I should not be talking about the rights of lesbian and gay people and I should stick to the issue of racial justice... But I hasten to remind them that Martin Luther King Jr. said "Injustice anywhere is a threat to justice everywhere."... I appeal to everyone who believes in Martin Luther King Jr.'s dream to make room at the table of brother- and sisterhood for lesbian and gay people.[272]

— Coretta Scott King, Metro Weekly

San Francisco City Supervisor Harvey Milk was the first openly gay man to be elected to office in the U.S. and spearheaded the defeat of statewide anti-gay ballot measure Proposition 6 in California in 1978. While he and Moscone were assassinated shortly thereafter, both became viewed as martyrs for gay rights. Milk's image as a positive role model led to him becoming the namesake for the first high school designed primarily for gay teenagers, the Harvey Milk High School, in the East Village of New York City.[281] The portrayal of those efforts in the critically acclaimed film Milk earned Sean Penn an Oscar and comparisons to the contemporary battle over the anti-gay ballot initiative Proposition 8 raging in California at the time of the film's release in 2008.[282]

An ironic icon is Anita Bryant, who worked to oppose homosexuality.[283] During the 1970s, Bryant led a national campaign, "Save Our Children", that conflated homosexuality and pedophilia and insisted that, because homosexuals cannot reproduce, they must "recruit" or "convert" people to their lifestyle.[284] California State Senator John V. Briggs applauded Bryant's work as a "national, religious crusade [and] courageous stand to protect American children from blatant homosexuality".[284] However, as Bruce C. Steele of The Advocate wrote, Bryant's crusade against the Gay Rights Movement made her synonymous with it.

About 10 years ago, I was at an American Booksellers Association convention where Bryant was ... still pissing and moaning about how the homosexuals had destroyed her career as spokesperson for Florida orange juice. The irony is, it wasn't the orange juice boycott that caused her to lose her job; it was the fact that she made herself forever associated with homosexuality. So, in one way, she was a victim of homophobia herself: Folks on the orange board didn't want people to think about queers when they bought orange juice."[283]

— as told to Bruce C. Steele, The Advocate

According to John Coppola, exhibit curator and former head of exhibits at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, DC, "In a completely unintended way, Anita Bryant was about the best thing to happen to the gay rights movement ... She and her cohorts were so over the top that it just completely galvanized the gay rights movement".[285] The 30th anniversary of Bryant's campaign against LGBT rights has been commemorated at the Stonewall Library & Archives, with executive director Jack Rutland dubbing her "The Mother of Gay Rights".[285]

Fictional

Various fictional characters have been regarded as gay icons, including cartoon figures. Bugs Bunny, a fictional anthropomorphic rabbit appearing in animation by Warner Bros. Cartoons during the Golden Age of American animation—dubbed the greatest cartoon character of all time by TV Guide—has been declared a "queer cultural icon [and] parodic diva" due to his "cross-dressing antics" and camp appeal.[286][287][288]

Some comic book characters are considered gay icons. Homosexual interpretations of Batman and the original Robin, Dick Grayson, have been of interest in cultural and academic study, due primarily to psychologist Fredric Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent (1954).[289] In the mid-1950s, Wertham led a national campaign against comic books, convincing Americans that they were responsible for corrupting children and encouraging them to engage in acts of sex and violence.[289] In relation to Batman and Robin, Wertham asserted "the Batman type of story helps to fixate homoerotic tendencies by suggesting the form of an adolescent-with-adult or Ganymede-Zeus type of love-relationship".[290]

In Containing America: Cultural Production and Consumption in Fifties America, authors Nathan Abrams and Julie Hughes point out that homosexual interpretations of Batman and Robin existed prior to Wertham's Seduction of the Innocent.[291] Wertham claimed his book was, in fact, prompted by the earlier research of a California psychiatrist.[291] The relationship between Batman and arch villain the Joker has also been interpreted by many as homoerotic. Frank Miller, author of The Dark Knight Returns, has described the relationship between Batman and the Joker as a "homophobic nightmare," and views the character as sublimating his sexual urges into crime fighting, concluding, "He'd be much healthier if he were gay."[292]

One TV series that appeals most to LGBT culture is the 1960s sitcom Bewitched. Aside from the campy characterizations, it contained three gay cast members (Dick Sargent, Paul Lynde and—allegedly—Agnes Moorehead). Star Elizabeth Montgomery and Sargent were grand marshals of a Los Angeles gay pride parade in the early 1990s. Another example is Bianca Montgomery of All My Children.[293]

Responses

Many celebrities have responded positively to being regarded as gay icons, several noting the loyalty of their gay fans. Eartha Kitt and Cher credited gay fans with keeping them going at times when their careers had faltered.[294] Kylie Minogue has acknowledged the perception of herself as a gay icon and has performed at such events as the Sydney Gay and Lesbian Mardi Gras. Asked to explain the reason for her large gay fanbase, Minogue replied, "It's always difficult for me to give the definitive answer because I don't have it. My gay audience has been with me from the beginning ... they kind of adopted me." She noted that she differed from many gay icons who were seen as tragic figures, with the comment, "I've had a lot of tragic hairdos and outfits. I think that makes up for it!"[295]

.jpg)

Tammy Faye Messner (ex-wife of fellow controversial televangelist Jim Bakker and mother of pastor Jay Bakker), who benevolently has been referred to as "the ultimate drag queen,"[296] said in her last interview with Larry King that, "When I went—when we lost everything, it was the gay people that came to my rescue, and I will always love them for that."[297]

Lady Gaga has acknowledged and credited her gay following for launching then supporting her career stating, among other examples, "When I started in the mainstream it was the gays that lifted me up" or "because of the gay community I'm where I am today." As a way to thanks her gay audience for having her in gay clubs for her first album before she was invited to perform at straight ones, she often debuted her new albums eras at gay clubs afterwards. Along her career, she also dedicated a MuchMusic Video Award win as well as her Alejandro music video to gay people, frequently praised her gay entourage for the positive impact they had on her life and often gave a place to different queer crowds in her songs, performances, music videos as well as in the visuals of her make up line. Lady Gaga is known for her fights as an LGBT activist and attended numerous LGBT events such as Prides and Stonewall day.[298][299][300][301][302][303][304]

Others have been more ambivalent. Mae West, a gay icon from the early days of her career, supported gay rights but bristled when her performance style was referred to as camp.[305]

Madonna has acknowledged and embraced her gay following throughout her career, even making several references to the gay community in her songs or performances, and performed at several gay clubs. She has declared in interviews that some of her best friends are gay and that she adores gay people and refers to herself as "the biggest gay icon of all times."[306] She also has been quoted in television interviews in the early 1990s as declaring the "big problem in America at the time was homophobia."

See also

References

- "Subjects of the Visual Arts: St. Sebastian". glbtq.com. 2002. Archived from the original on September 1, 2007. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- Kaye, Richard A. (1996). "Losing His Religion: Saint Sebastian as Contemporary Gay Martyr". Outlooks: Lesbian and Gay Sexualities and Visual Cultures. Peter Horne and Reina Lewis, Eds. New York: Routledge. 86: 105. doi:10.4324/9780203432433_chapter_five.

- "Tiny Rep presents Suddenly, Last Summer" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on September 28, 2007. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- Vatican comes out of the closet and embraces Oscar; Richard Owen, The Times; January 5, 2007. Retrieved October 14, 2007.

- Fraser, Antonia (2001). Marie Antoinette: The Journey. New York: Anchor. p. 449. ISBN 0-385-48949-8.

- Castle, Terry (1993). The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 126–149 and 261n56. ISBN 0-231-07652-5.

- Euan Ferguson, Daniela's still dying for it; February 16, 2003; Retrieved February 8, 2007: All over the South-East men fell in lust with the idea of a fast lippy sexy Scot, and I'm told she also became something of a dykon, a female gay icon.

- Abernethy, Michael (November 16, 2006). "Queer, Isn't It?: Gay Icons: Judy Who?". PopMatters. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- Pramaggiore, Maria (February 1997). "Fishing For Girls: Romancing Lesbians in New Queer Cinema". College Literature. 24 (1): 59–75. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved February 9, 2007.

- Kennedy, Elizabeth Lapovsky; Madeline D. Davis (1994). Boots of Leather, Slippers of Gold: The History of a Lesbian Community. New York: Penguin. pp. 212–213. ISBN 0-14-023550-7.

- Blackman, Inge; Kathryn Perry (1990). "Skirting the Issue: Lesbian Fashion for the 1990s". Feminist Review. 0 (34): 67–78. doi:10.2307/1395306. JSTOR 1395306.

- Halberstam, Judith (1998). Female Masculinity. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. p. 330. ISBN 0-8223-2243-9.

- Ortega, Teresa. "'My Name is Sue! How do you do?': Johnny Cash as Lesbian Icon". In Tichi, Cecilia (1998). Reading Country Music: Steel Guitars, Opry Stars, and Honky-Tonk Bars. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. p. 222. ISBN 0-8223-2168-8.

- Flynn, Paul (May 16, 2006). "Margaret Thatcher: gay icon". The Guardian. London. Retrieved April 17, 2017.

- "Gay Montmartre Tour". Archived from the original on January 17, 2008. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- France, David (February 2007). "Dying to come out:The war on gay people in Iraq". GQ magazine. Archived from the original on May 13, 2007. Retrieved February 7, 2007.

- "PeopleMeet Navin Noronha, India's first openly gay stand-up comedian who is also an engineering graduate!". edxlive.com. August 11, 2018. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- "Here's how Anil Kapoor became the newest gay icon!". Bollywoodlife.com. September 8, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- "Is Sonam Kapoor India's new gay icon? - Rediff.com Movies". Rediff.com. June 27, 2011. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- "Jolin Tsai on LGBTQ representation in her music". Billboard.com.

- Ho, Gwyneth (April 9, 2018). "Leslie Cheung: Asia's gay icon lives on 15 years after his death - BBC News". BBC News. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- "Korea's biggest pop group Girls Generation comes out for LGBTI rights". Gay Star News. August 9, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2020.

- "Tina rules the waves". The Nation.com. May 28, 2016. Retrieved April 28, 2019.

- "Foot and Hand Prints in Rotterdam". Gayinfo.tripod.com. Archived from the original on February 14, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- «Fallece Pedro Zerolo, un icono del activismo LGTB.»

- The Guardian (August 13, 2006). 'Sex was my way of coping with death' (interview with Pedro Almodóvar). Retrieved June 14, 2008.

- "El Papa es impopular entre gays". Los Tiempos. January 17, 2007. Archived from the original on November 10, 2007. Retrieved June 22, 2008.

- "Joss, Lionel & Jimmy Play Dublin..." ShowBiz Ireland. April 11, 2004. Archived from the original on June 3, 2013. Retrieved November 26, 2007.

- Hildegard Knef. Eine Künstlerin aus Deutschland. ASIN 3865051677.

- Kort, Michele (April 27, 1999). "The secret life of Dusty Springfield". The Advocate. Archived from the original on May 6, 2005. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- "Murder on the dance floor: a quick tango with Sophie Ellis-Bextor". The Standard. Retrieved October 21, 2013.

- "Pourquoi Mylène Farmer est-elle une icône gay? – Têtu". Tetu.com. Archived from the original on April 17, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- Matson, Michael (November 22, 2010). "Ukraine's Hottest Boy Band". Geek Out. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved November 22, 2010.

- "Türkiye'nin 'gay ikonu' Hande Yener". Archived from the original on November 5, 2013. Retrieved January 19, 2012.

- "Isabella Rossellini: Fashion and Gay icon to make film series". The New Gay. May 3, 2010. Archived from the original on March 12, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- "An anti-diva returns to thank her fans". Houston Chronicle. January 10, 2008. Retrieved July 18, 2009.

- Gonzalez, Lisa (June 11, 2009). "Paulina Rubio Inspired By Miami For New Album And Video". Mtv. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- "Alaska says we should refer to "gay" as a positive thing". Agmagazine.info. June 20, 2009. Archived from the original on April 7, 2012. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- "Enrique Loves Gay Life – Softpedia". News.softpedia.com. Archived from the original on December 23, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- "Iconos y técnicas de conquista en la primera enciclopedia gay argentina". Ñ (in Spanish). Clarín. December 29, 2009. Archived from the original on November 11, 2013. Retrieved November 10, 2013.

- "Meu público gay agora tem idade para ir a boates, diz Kelly Key". Brazil: G1 News. June 14, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- ""Eu sou a favor do casamento gay", revela Sandy em entrevista". Brazil: Virgula Uol News. June 14, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- "Público gay foi o primeiro a abraçar novo trabalho, diz Wanessa Camargo". Brazil: G1 News. June 14, 2012. Retrieved June 17, 2012.

- "Gays criticam Dilma, Crô e Minotauro e entregam "Oscar"". Terra. August 17, 2012. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- Sikov, Ed (2007). Dark Victory: The Life of Bette Davis. Macmillan. p. 139. ISBN 978-0-8050-7548-9.

- Dunn, Andrew (December 25, 2001). "Review: 'Dietrich' beautiful photo collection". CNN.com. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- Althaus-Reid, Marcella (2006). Liberation Theology and Sexuality. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 134. ISBN 0-7546-5080-4.

- "Carol Channing remembered by LGBTQ community as 'gay icon'". NBC News. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- Westley, Michael (August 13, 2002). "Cher: Last of the Gay Icons?". Salt Lake Tribune. Archived from the original on September 30, 2007. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- Bronski, Michael (1984). Culture Clash: The Making of Gay Sensibility. South End Press. p. 104. ISBN 0-89608-217-2.

- Cage, Ken; Moyra Evans (2003). Gayle: The Language of Kinks and Queens, A History and Dictionary of Gay Language in South Africa. Jacana Media. p. 10. ISBN 1-919931-49-X.

- Bret, David (2008). Joan Crawford: Hollywood Martyr. Da Capo Press. pp. 192, 287. ISBN 978-0-306-81624-6.

- Quirk, Lawrence J.; William Schoell (2002). Joan Crawford: The Essential Biography. University Press of Kentucky. p. 235. ISBN 0-8131-2254-6.

- Tannen, Lee (2002). I Loved Lucy: My Friendship With Lucille Ball. St. Martin's Press. Macmillan. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-312-30274-0. Retrieved January 24, 2008.

- Grew, Tony (January 5, 2007). "Gordon Ramsay 50th most popular gay icon". Pink News. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- Creswell, Toby (2006). 1001 Songs: The Great Songs of All Time and the Artists, Stories and Secrets Behind Them. Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 175. ISBN 1-56025-915-9.

- Flynn, Paul (May 18, 2012). "RIP Donna Summer – the accidental gay icon". The Guardian. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- Sagert, Kelly Boyer (2007). The 1970s. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 183. ISBN 978-0-313-33919-6.

- "Village People – Gay Icons". Astabgay.com. March 4, 2001. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- Bugg, Sean (June 6, 2013). "Pride's Wonder Woman". Metro Weekly. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- Peeples, Jase (April 24, 2012). "The Further Adventures of Lynda Carter". Out. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- "Sylvester: Remembering the LGBTQ Pioneer's Inspirational Life". June 30, 2017.

- "Bette Midler". Houston Voice. October 23, 1998.

- R. Jay Magill (July 16, 2012). Sincerity: How a moral ideal born five hundred years ago inspired religious wars, modern art, hipster chic, and the curious notion that we all have something to say (no matter how dull). W. W. Norton. p. 163. ISBN 978-0-393-08419-1.

- Januszczak, Waldemar (November 17, 1996). "Star of India". The Sunday Times. London.;Cain, Matthew, dir. (2006). "Freddie Mercury: A Kind of Magic". London: British Film Institute...;Landesman, Cosmo (September 10, 2006). "Freddie, a Very Private Rock Star". The Times. London. Retrieved May 2, 2010.

- Patricia Juliana Smith (2002). "Mercury, Freddie (1946-1991)" (PDF). glbtq Inc. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- Jamie Tabberer (December 1, 2014). "Never forget: 9 gay icons who lost their lives to HIV and AIDS". Gay Star News. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- Helen Hok-Sze Leung. "Undercurrents: Queer Culture and Postcolonial Hong Kong". p. 88. HBC Press.

- "Zanzibar angry over Mercury bash". BBC News. London. September 1, 2006. Retrieved January 4, 2010.;Fitzpatrick, Liam (November 13, 2006). "Farookh Bulsara". Time Magazine, Asia Edition. 60 Years of Asian Heroes. 168 (21). Hong Kong: Time Asia. Archived from the original on December 28, 2008.

- Gilmore, Mikhal (July 7, 2014). "Queen's Tragic Rhapsody". Rolling Stone. Retrieved September 6, 2015.

- Hutton, Jim; Waspshott, Tim (1994), Mercury and Me, London: Bloomsbury, ISBN 0-7475-1922-6

- "1991: Giant of rock dies". News.bbc.co.uk. November 24, 1991. Retrieved September 27, 2014.

- Louis A Bustamante (July 2, 2007). "Deborah Harry News: SF Gate: Gay icons rock Berkeley for a cause in post-Pride 'True Colors' celebration". Deborahharry.com. Archived from the original on July 9, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- Devitt, Rachel (March 29, 2011). "Cheat Sheet: Gay Icons – Rhapsody: The Mix". Blog.rhapsody.com. Archived from the original on June 3, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- Wieder, Judy (May 11, 1999). "Stop! In the name of love". The Advocate. Archived from the original on March 19, 2005. Retrieved January 11, 2008.

- Charo: From 'Love Boat' to Pride parade float Carolyne Zinko, San Francisco Chronicle; June 29, 2008.

- "You ask the questions (Such as: so, Elaine Paige, have you ever sung in a karaoke bar?)". The Independent. London. June 7, 2000. Retrieved January 29, 2008.

- Bolcer, Julie. "Dolly Parton: I'm for Gay Marriage". The Advocate. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- "Lesbian and Gay Icons". Retrieved July 24, 2007.

- "Why Lady Gaga Is Not a Gay Icon and Whitney Houston Is". Stephen Ira. February 17, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2012.

- "Interview with gay ally Olivia Newton-John". AfterElton. August 13, 2008. Archived from the original on June 14, 2012.

- "Rufus picks his gay icons". The Guardian. London. November 10, 2006.

- Frank, Steven (September 25, 2005). "What Does It Take to Be a Gay Icon Today?". After Elton. Archived from the original on December 10, 2007. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- Leboeuf, Tony (May 3, 2005). "Be My Idol". Time Out. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- "David Bowie: An Icon for All Music Generations". Archived from the original on September 23, 2008. Retrieved May 4, 2009.

- "Elton John". Gay.com. Archived from the original on July 2, 2005. Retrieved April 24, 2008.

- Portwood, Jerry (June 12, 2017). "25 Essential Gay Pride Songs: Rolling Stone Editor Picks – Rolling Stone". Rollingstone.com. Retrieved October 21, 2018.

- Bernstein, Robert (2003). Straight Parents, Gay Children: Keeping Families Together. Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 166. ISBN 1-56025-452-1.

- Plumez, Jacqueline Hornor (2002). Mother Power. Sourcebooks, Inc. p. 182. ISBN 1-57071-823-7.

- Mann, William J. (2004). Gay Pride: A Celebration of All Things Gay and Lesbian. Citadel Press. p. 14. ISBN 0-8065-2563-0.

- Cross, Mary (2004). Madonna: A Biography. Canongate U.S. ISBN 0-313-33811-6.

- Bowman, Edith (May 26, 2007). "BBC World Visionaries: Madonna Vs. Mozart". BBC News. Archived from the original on May 25, 2008. Retrieved May 12, 2008.

In 2000, Guinness World Records listed Madonna as the most successful female recording artist of all time.

- Gdula, Steve (November 11, 2005). "Happy Madonna day!". Archived from the original on November 19, 2006. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- Guilbert, Georges-Claude (2002). Madonna As Postmodern Myth: How One Star's Self-Construction Rewrites Sex, Gender, Hollywood and the American Dream. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-1408-1. Retrieved July 9, 2008.

- Taraborrelli, J. Randy (2002). Madonna: An Intimate Biography. Simon and Schuster. p. 147. ISBN 0-7432-2880-4.

- "Cyndi Lauper to Perform at National Forum". Equality Forum press release. February 24, 2005. Archived from the original on June 7, 2007. Retrieved August 1, 2007.

- Creekmur, Corey K.; Doty, Alexander (1995). Out in Culture: Gay, Lesbian, and Queer Essays on Popular Culture. Duke University Press. p. 420. ISBN 0-8223-1541-6.

- Stites, Jessica (June 30, 2008). "She Still Bops". The Advocate. Archived from the original on July 26, 2008. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- Lauper, Cyndi (June 11, 2008). "Here's Where I'm Coming From". The Advocate. Archived from the original on June 28, 2011. Retrieved July 11, 2008.

- "Freaks Talk Back: Tabloid Talk Shows and Sexual Nonconformity, Gamson". Press.uchicago.edu. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- Abt, Vicki; Mustazza, Leonard (1997). Coming after Oprah: Cultural Fallout in the Age of the TV Talk Show (9780879727529): Vicki Abt, Leonard Mustazza: Books. ISBN 0879727527.

- "GLAAD Glad Name Media Award Nominees / Queerty". Queerty.com. January 21, 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- Keith Boykin (March 27, 2007). "Patti LaBelle Wins GLAAD Media Award". Keithboykin.com. Archived from the original on November 21, 2008. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- "Cynthia Nixon, Joy Behar win gay media awards – Arts & Entertainment – CBC News". Canada: CBC. March 14, 2010. Archived from the original on March 17, 2010. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- "'Precious,' 'A Single Man' Among GLAAD Nominees". Archived from the original on July 6, 2011. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- Wightman, Catriona (January 10, 2010). "Lambert "really excited" about Oprah". Digitalspy.com. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- "Tina Arena Spectacular - Gay & Lesbian - Time Out Sydney". Au.timeout.com. Archived from the original on May 19, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- "Queen of Quirky". Archived from the original on November 6, 2007. Retrieved March 18, 2009.

- Taylor, Maggie (July 22, 2008). "Thank You for Being a Friend; Golden Girls' Estelle Getty Dead at 84". GayWired.com. Archived from the original on December 6, 2008. Retrieved July 24, 2008.

- D'Argy, Marcelle (April 22, 2001). "Joan Collins: She's younger by the minute". The Independent. London. Retrieved April 14, 2010.

- "Diva Annie Lennox Sings... Live..." GTMagazine. September 2007. Archived from the original on October 14, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2007.

- "In News Weekly May 2, 2001 Nicks of Time By Lawrence Ferber". Rockalittle.com. May 2, 2001. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- Magazine Staff. "Gay Entertainment Report: Stevie Nicks As Gay Icon". On Top Magazine. Archived from the original on September 9, 2012. Retrieved October 1, 2016.

- Goldberg, M. (May 2, 1991). "The Jacksons score big". Rolling Stone. p. 32. ISSN 0035-791X.

- "Janet Jackson Hits Big; $80 Million Record Deal". Newsday. January 13, 1996. pp. A02.

- McCormick, Neil (October 18, 1997). "The Arts: Give her enough rope... Reviews Rock CDs". The Daily Telegraph. p. 11.

- McCarthy, Marc (April 1, 2008). "Janet Jackson to be Honored at 19th Annual GLAAD Media Awards in Los Angeles". GLAAD. Archived from the original on April 9, 2008. Retrieved April 1, 2008.

- "La Toya Jackson Learns Life's Lessons". gaywired.com. June 2005. Archived from the original on October 23, 2005. Retrieved December 21, 2007.

- Rule, Doug (April 7, 2010). "The Musical Empowerment of Deborah Cox – Metro Weekly". Metroweekly.com. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- "Gayly's exclusive interview with the sensational Deborah Cox". The Gayly. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- "Deborah Cox returns to Orlando for GayDays". Watermark Online. May 26, 2011. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- "Ysa Ferrer, icône gay, star en Russie, veut élargir son public, ce soir à Lille - La Voix du Nord". Lavoixdunord.fr. Archived from the original on April 27, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- "Nordeclair.fr". Nordeclair.fr. Archived from the original on April 26, 2014. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- "Glenn Close: Yep, I'm a Gay Icon!". PEOPLE.com. April 30, 2002. Retrieved December 24, 2016.

- "Garth backs us gays=dallasvoice". July 12, 1996. Archived from the original on January 2, 2017. Retrieved July 12, 2016.

- "Emma Bunton Interview". dancemusic.about.com. Archived from the original on September 17, 2005. Retrieved 13 February 2017.

- "G-A-Y founder takes back nightclub chain from HMV". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved February 4, 2013.

- "Geri Power – Metro Weekly". Metroweekly.com. November 10, 1999. Retrieved May 19, 2014.

- Top 50 gay icons. femin.co.uk. Retrieved 17 January 2008. Archived January 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- "Interview: Geri Horner talks Spice Girls, solo regrets, and her kinship with the gay community". Attitude. January 5, 2017. Retrieved February 13, 2017.

- https://www.therainbowtimesmass.com/heroism-of-mariah-carey/

- https://www.vice.com/en_us/article/rnw8jq/how-the-gay-icon-in-music-has-evolved

- https://www.mic.com/articles/143485/mariah-carey-just-explained-what-lgbtq-truly-stands-for-at-glaad-media-awards

- Boucher, Geoff (January 4, 2001). "Grammys Cast a Wider Net Than Usual". Los Angeles Times. Tribune Company. p. 13. Retrieved April 29, 2011.

- "The pink hit parade: Sing if you're glad to be gay". The Independent. London. November 1, 2006. Retrieved April 26, 2009.

- Lucy Ellis, Bryony Sutherland. Kylie "Talking": Kylie Minogue in Her Own Words. Omnibus Press, 2003. ISBN 978-0-7119-9834-6. p. 47

- Ives, Brian; Bottomley, C. (February 24, 2004). "Kylie Minogue: Disco's Thin White Dame". VH1. Retrieved January 21, 2007.

- Pemberton, Andy. "Danni Minogue, gay icon, wants John Mayer for obvious reasons". Musictoob. Archived from the original on May 3, 2010. Retrieved August 9, 2015.

- Jackson, Joe (September 12, 2004). "Finding the joy in sorrow". Sunday Independent. Independent News & Media. Retrieved September 12, 2004.

Was Crowley, who would later become a figure of romantic longing for TV viewers - male and, presumably, female, given that she was once cited as a gay icon - always aware of how attractive she is?

- Szymanek, Lukas (2004). "Chasing Megan Mullally". Lumino Magazine. Archived from the original on July 18, 2011. Retrieved April 24, 2010.

- Hernandez, Greg (April 23, 2008). "Out in Hollywood". Insidesocal.com. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- "Christina Aguilera's Beautiful named most-empowering gay anthem of the decade! « The Rainbow Post". Therainbowpost.com. April 8, 2011. Archived from the original on August 31, 2011. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- "Christina Aguilera honored at debut of The Abbey's Gay Walk of Fame (photos) (ChicagoPride.com : West Hollywood, CA News)". Chicago.gopride.com. Retrieved June 16, 2011.

- "Christina Aguilera Celebrates The Gays By Getting Dirty [PHOTOS]". Socialite Life. April 21, 2011. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- "Christina Aguilera Is Honored On The Gay Walk Of Fame". Pink is the New Blog. April 21, 2011. Archived from the original on December 4, 2011. Retrieved December 9, 2011.

- "TIME 100 Next 2019: Mj Rodriguez". Time. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- Blum, Steven (May 20, 2019). "100-Plus LGBTQ Icons and Iconoclasts Who Are Shaping Culture in L.A. and Beyond". Los Angeles Magazine. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- Campaign, Human Rights. "Ricky Martin, Dominique Jackson at the HRC National Dinner". Human Rights Campaign. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- "Angelica Ross Accepts Visibility Award from the Human Rights Campaign". Miss Ross. November 16, 2016. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- "How Lily Tomlin Became a Lifelong Advocate for the L.A. LGBT Center". www.advocate.com. September 20, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- Elliott, Mark (June 11, 2019). "LGBTQ Musicians: 15 Pioneering Icons That Helped Fans Find Their Voice". uDiscover Music. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- shanicave (July 5, 2017). "10 Chinese LGBTQ Icons". Project Pengyou. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- Tungol, J. R.; professional, ContributorNYC-based media (October 29, 2012). "PHOTOS: The Most Influential LGBT Asian Icons". HuffPost. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- "The controversial moment that led George Michael to publicly acknowledge he was gay". Independent.

- "Elton John and Judy Garland ranked top gay icons". PinkNews.

- Mark, Allen. "Comedian Eric Andre: The Gay Interview". Towler Road. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- "Lance Bass, Fiance Michael Turchin to Get Married on TV: Will *NSYNC Perform at the Wedding?". Latin Post.

- "The 12 Greatest Female Gay Icons of All Time". out.com.

- Smith, Tom. "The Most Important LGBT Icons in Australia". Culture Trip. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Gordon Ramsay 50th most popular gay icon - PinkNews.co.uk". June 4, 2011. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved January 28, 2020.

- Justine Ashley Costanza (September 26, 2012). "Neil Patrick Harris New Book: From Child Star To Gay Icon And Everything In Between". International Business Times.

- Bruna Nessif (May 5, 2016). "Colton Haynes Comes Out as Gay: "I'm Happier Than I've Ever Been"". E! News. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- CNN Wire Staff (October 16, 2011). "Actor Zachary Quinto comes out in honor of bullied teen". CNN. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- THR Staff (February 13, 2012). "'White Collar's' Matt Bomer Officially Comes Out as Gay at Awards Show". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Daniel D'Addario (October 10, 2014). "Luke Evans Has Been Out for Years, But He's Finally Stopped Hiding". Time. Retrieved June 1, 2019.

- Queer Voices (August 21, 2013). "Wentworth Miller Comes Out: 'Prison Break' Star Reveals He's Gay". The Huffington Post. Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- Jack'd (June 5, 2014). "Michael Sam, Frank Ocean and Iggy Azalea Voted as Top New Gay Icons... -- BOSTON, June 5, 2014 /PRNewswire/ --". prnewswire.com.

- "Michelle Visage Reveals Her Favorite Gay Icon to Gay Times". World of Wonder.

- Mic. "How George Takei Went From Being a Trekkie to a Gay Rights Hero". Mic.

- "Tony Blair named as one of top gay icons of past 30 years". The Guardian. September 26, 2014.

- Christina Hendricks Appreciates her status as a gay icon

- Matson, Michael (November 19, 2015). "Sarah Paulson on Cats Blanchett, Carol, Coming Out and Jessica Lange". Out. Retrieved November 19, 2015.

- https://www.nbcnews.com/news/amp/ncna1057636

- "My Top Ten Queer Icons". The Odyssey Online. June 30, 2017. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- https://www.pinknews.co.uk/2019/06/18/lgbt-icon-billy-porter-headline-pride-london/

- Blum, Steven (May 20, 2019). "100-Plus LGBTQ Icons and Iconoclasts Who Are Shaping Culture in L.A. and Beyond". Los Angeles Magazine. Retrieved May 16, 2020.

- "Billboard Named Ariana Grande the 'Gay Icon of Her Generation' and People Are...Confused?". pride.com. July 20, 2018.

- "Ariana Grande is officially THE gay icon of this generation". LGBTeen.

- "8 Times Lady Gaga Earned Her 'Gay Icon' Title". Billboard. Retrieved December 27, 2019.

- "See 6 Times Katy Perry Stood Up in Support of the LGBTQ Community". Billboard. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- "GLAAD to honor Adam Lambert at the #glaadawards in San Francisco". GLAAD. March 28, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2018.

- "appeal of Dua Lipa". Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- "I Wish I'd Been a Bad Girl". Retrieved December 15, 2019.

- Pollard, Alexandra (February 22, 2018). "How Hayley Kiyoko Became Pop's 'Lesbian Jesus'". Out. Retrieved March 31, 2018.

- Duffy, Stuart. "Gay icon Lily Allen to perform in Scotland". KaleidoScot.

- "Watch The Trailer For 'Maleficent,' Which Sure Seems Destined For a Big Gay Following". Oliver Skinner.

...and it's all set to a cover of "Once Upon a Dream" by undeniable gay icon Ms. Lana Del Rey.

- "Taylor Swift Donates $113,000 to Tennessee Equality Project to Fight Anti-LGBTQ Bills". Billboard.com.

- "Marina and the Diamonds On Nervous Breakdown, Gay Following & Being One of the 'Greats'". Pride Source. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- "Queen Of The Underdogs: 5 Reasons Pink Is an Underappreciated Gay Icon". Billboard. Retrieved April 2, 2018.

- "Gay Icons: 25 Divas Who Have Been Embraced by Gay Culture". The Huffington Post.

- "Christina Aguilera hailed for inspiring LGBTQ community". IrishExaminer.

- "Miley Cyrus On Gay Fans, Same-Sex Marriage And Why London Is Her Favorite City". The Huffington Post. January 1, 2013.

- "HRC to Honor Jennifer Lopez with Ally for Equality Award". Human Rights Campaign.

- Billboard https://www.billboard.com/articles/news/pride/7941086. Retrieved March 14, 2018. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Carly Rae Jepsen: My Relationship With My Gay Fans Is A 'Mutual Lovefest'". The Huffington Post.

- country, About the Author Matthew Wade Matthew Wade is the Editor of Star Observer When he isn't covering the latest LGBTI news across the; Cinema, He Indulges in Queer (August 23, 2017). "Charli XCX: the LGBTI community were the first to celebrate my music". Star Observer. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- Dalton, Deron; journalist, ContributorMulticultural Web (March 31, 2013). "Gay Icons: 25 Divas Who Have Been Embraced By Gay Culture". HuffPost. Retrieved March 7, 2020.

- shanicave (July 5, 2017). "10 Chinese LGBTQ Icons". Project Pengyou. Retrieved April 7, 2020.

- "Kim Petras: Inside the Fantasy and Behind the Bops". out.com. October 17, 2018. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- McErlane, Fern (February 15, 2019). "Is SOPHIE the unapologetic LGBTQ+ icon we need?". The Gryphon. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- Williscroft-Ferris, Lee (November 12, 2016). "Björk: A queer icon". Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- "Fifty Years of Queer Icon Kylie Minogue". intomore.com. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- "5 Reasons Stevie Nicks Is, In Fact, a Gay Icon". billboard.com. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- "Why Demi Lovato is an LGBT icon: Her fearless takes on sexuality, addiction and mental illness". PinkNews.

- "Idina Menzel on Working Toward LGBT Icon Status, a Lesbian Elsa & Angry Gays Who Oppose Her 'Beaches' Remake".

- "Gay Icons | The 18 Greatest Gay Male Icons Of Our Generation". rukkle. October 28, 2015. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- "Adele voted new gay icon". Hindustan Times. April 22, 2012. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- Yang, Matt Rogers, Bowen (March 30, 2018). "Kacey Musgraves Is a Gay Icon and the World Needs to Know". Vulture. Retrieved March 28, 2020.

- "In Conversation With Elizabeth "CupcakKe" Harris". October 28, 2016.

- "CupcakKe's new single Crayons is the LGBTQ anthem we've been waiting for". March 26, 2018.

- Mel B is a gay icon on out.com

- Mel B gay icon sur gaystarnews.com

- Mel B is a gay icon on pridesource.com

- Mel B happy to be known as a gay icon on dnaindia.com

- "Tyra Banks, Suze Orman Honored at 20th Annual GLAAD Media Awards Presented by IBM". GLAAD. March 29, 2009.

- "Tyra, Clay Aiken, Suze Orman Get GLAAD in NYC". Logo TV. March 30, 2009.

- "LGBT+ Icons in Japan". All About Japan. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- "#BornThisDay: Gay Icon, Jane Fonda". The WOW Report. December 21, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- "'Grandma's joining': Jane Fonda arrested at climate-change protest". PinkNews - Gay news, reviews and comment from the world's most read lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans news service. October 12, 2019. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- "'I'm Proud To Be A Gay Icon!': Angela Lansbury Opens Up In New Interview". Entertainmentwise. January 25, 2014. Archived from the original on July 4, 2015. Retrieved April 7, 2014.

- Wong, Curtis M. (May 14, 2014). "Whoopi Sounds Off On Those Long-Standing Lesbian Rumors". HuffPost. Retrieved February 15, 2020.

- "Kathy Griffin Talks Paltrow, Kidman, and Keeping It Real". Los Angeles Magazine. June 1, 2005.

- "Gay Iconography: Do You Love Or Loathe Kathy Griffin?". Towleroad. February 8, 2014.

- "Ryan Murphy Interviews Jessica Lange on Fame, Feuds & the Feminine Mystique". out.com. February 28, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- "5 Ways Carrie Fisher Helped The LGBTQ Community". Hornet. December 28, 2016.

- Smith, Tom. "The Most Important LGBT Icons in Australia". Culture Trip. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Xena Likes Being A Lesbian Icon". New York Post. February 17, 1999. Retrieved March 7, 2017.

- "An interview with Lucy Lawless". AfterEllen.com. January 7, 2011. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- "It's three days into 2020 and the internet has declared its first gay icon, Casualty star Amanda Henderson". PinkNews - Gay news, reviews and comment from the world's most read lesbian, gay, bisexual, and trans news service. January 3, 2020. Retrieved January 27, 2020.

- "Mo'Nique". getoutmag.com. November 22, 2015.

- "Top 10 Gay Icon Dames". The Gay UK Magazine. December 31, 2014. Archived from the original on March 17, 2017. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- "Alluring qualities that make a gay icon". The Independent. October 2, 1992.

- Tungol, J. R.; professional, ContributorNYC-based media (October 29, 2012). "PHOTOS: The Most Influential LGBT Asian Icons". HuffPost. Retrieved April 16, 2020.

- "New Gay Icon: Leslie Grossman Talks 'AHS', Mary Cherry, and Gay Friends". www.out.com. September 26, 2018. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- "Why Is Laura Dern a Gay Icon?". PAPER. February 14, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- "How a Gay 'Fanboy' Created an Unforgettable Laura Dern Tribute". www.advocate.com. February 13, 2020. Retrieved February 14, 2020.

- "Patricia Clarkson's Publicists Asked For Fake, LGBT-Supporting Memes About Her To Be Taken Down". Buzzfeed. January 16, 2019. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- "Meryl Streep to Be Honored With Major LGBT Award (Exclusive)". The Hollywood Reporter. December 20, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- "Meryl Streep talks sexting, becoming a gay icon — 'I just can't remember when LGBT people were not in my life'". New York Daily News. August 10, 2016. Retrieved March 17, 2017.

- Domnu, Rosie (December 19, 2020). "Catherine O'Hara Hopes Schitt's Creek Inspires Queer Representation".

- Hardnick, Chris (May 10, 2020). "An Ode to Moira Rose of Schitt's Creek, the Most Delightfully Absurd Mother on TV: Catherine O'Hara gave TV audiences one memorable character in Moira Rose on Schitt's Creek". E News. Retrieved May 10, 2020.

- Wong, Curtis M. (October 22, 2014). "Lisa Kudrow: 'Gay Men Are Superior Beings In My Mind'". Huffington Post.

- Combs Marr, Zoe (June 8, 2020). "The Comeback: Lisa Kudrow is perfect in hilarious, biting and deeply meta satire".

- Clarendon, Dan (December 19, 2019). "Timothée Chalamet learns he's the 'straight prince of twinks'". Queerty.

- Duff, Nick (February 11, 2019). "Rachel Weisz and Olivia Colman's 'gay rights' BAFTAs moment driving fans wild". Pink News.

- Megarry, Daniel (May 30, 2019). "Watch Rocketman star Taron Egerton read out thirsty tweets from fans". Gay Times.

- "The Greatest Gay Icons in Film". Ranker. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Gay Icons | The 18 Greatest Gay Male Icons Of Our Generation". rukkle. October 28, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2020.

- Grant, David (February 19, 2020). "PHOTO: Richard Madden leaves fans parched with latest thirst trap". Queerty.

- Damshenas. "Watch Colton Haynes hit on Nick Robinson in deleted scene from Love, Simon". Retrieved May 29, 2020.

- Gilchrist, Tracey E (September 12, 2018). "Lizzie's Chloë Sevigny Will Never Play Trans Again". Adovocate.

- Gutowitz, Jill (February 22, 2019). "How Rachel Weisz Became the Unofficial Straight LGBTQ Ambassador". Vice.

- Perry, Grace (October 29, 2019). "The Problem With Queer Thirst For Straight Celebrities". Buzzfeed.

- Breen, Matthew (June 18, 2013). "National Gay & Lesbian Sports Hall of Fame's Inaugural Class Announced". out.com. Retrieved June 18, 2013.

- "Lesbian tennis star becomes a pioneer for women's rights". April 26, 2006. Archived from the original on December 15, 2006. Retrieved January 15, 2007.

- "Tom Daley at 20: Plymouth Schoolboy and Olympic Diving Star to Gay Icon". International Business Times. May 21, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- "Robbie Rogers: The aftermath of a gay footballer coming out". CNN. January 9, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2017.

- "MICHAEL SAM, FRANK OCEAN VOTED 2014'S TOP GAY ICONS". Attitude. June 6, 2014. Retrieved February 24, 2017.

- "Institutionalized homophobia in men's figure skating". outsports.com. February 4, 2014. Retrieved April 1, 2017.

- Donnelly, Grace (February 12, 2018). "Olympians Adam Rippon and Gus Kenworthy on Mike Pence, Visibility, and Becoming Gay Icons". Fortune. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- Stroude, Will (November 12, 2015). "Gus Kenworthy talks about Sochi, first sexual experiences and becoming a gay role model". Attitude. Retrieved October 15, 2017.

- Tom Smith. "The Most Important LGBT Icons in Australia". Culture Trip. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- "Rugby legend and LGBT icon Gareth Thomas comes to Portsmouth Guildhall". teamlocals.co.uk. July 30, 2015. Archived from the original on April 1, 2017. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- "The Pink List 2010". The Independent. July 31, 2010. Retrieved March 24, 2017.

- El legado de Pedro Zerolo

- Gage, Simon; Lisa Richards; Howard Wilmot; Boy George (2002). Queer. Thunder's Mouth Press. p. 17. ISBN 1-56025-377-0.

- "Kate Middleton is an 'icon' to lesbian people, says Tipping the Velvet author Sarah Waters". The Telegraph. London. April 21, 2011. Archived from the original on April 24, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- Hawgood, Alex (June 23, 2017). "These World Leaders Are the New Gay Icons". The Cut. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

- "Brian Sims". Retrieved March 16, 2017.

- "LGBTQ Equality".

- "Gay icon yields lessons after 30 years". NBC News. November 27, 2008. Retrieved April 9, 2012.

- O'Bryan, Will (February 16, 2006). "Losing an Ally: Gay leaders mourn the death of Coretta Scott King, mull the future of the King legacy for GLBT civil rights". Metro Weekly. Retrieved April 10, 2008.

- "Invisibility: Gay Icons in U.S. History". panel event. Equality Forum 2005. April 26, 2005. Archived from the original on November 13, 2006. Retrieved January 16, 2007.

- Labruce, Bruce (April 13, 2000). "In praise of the Bitch Goddess". Archived from the original on September 27, 2007. Retrieved January 15, 2007.