Ganymede (mythology)

In Greek mythology, Ganymede /ˈɡænɪmiːd/[1] or Ganymedes /ɡænɪˈmiːdiːz/[2] (Ancient Greek: Γανυμήδης Ganymēdēs) is a divine hero whose homeland was Troy. Homer describes Ganymede as the most beautiful of mortals, and in one version of the myth, Zeus falls in love with his beauty and abducts him in the form of an eagle to serve as cup-bearer in Olympus.

[Ganymedes] was the loveliest born of the race of mortals, and therefore

the gods caught him away to themselves, to be Zeus' wine-pourer,

for the sake of his beauty, so he might be among the immortals.

The myth was a model for the Greek social custom of paiderastía, the socially acceptable romantic relationship between an adult male and an adolescent male. The Latin form of the name was Catamitus (and also "Ganymedes"), from which the English word catamite is derived.[4] According to Plato, the Cretans were regularly accused of inventing the myth because they wanted to justify their "unnatural pleasures".[5]

Family

Ganymede was the son of Tros of Dardania,[6][7][8] from whose name "Troy" was supposedly derived, either by his wife Callirrhoe, daughter of the river god Scamander,[9][10][11] or Acallaris, daughter of Eumedes.[12] Depending on the author, he was the brother of Ilus, Assaracus, Cleopatra and Cleomestra. [13]

The traditions about Ganymede, however, differ greatly in their detail, for some call him a son of Laomedon,[14][15] others a son of Ilus[16] in some version of Dardanus[17] and others, again, of Erichthonius[18] or Assaracus.[19]

| Relation | Names | Sources | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Homer | Homeric Hymns | Euripides | Diodorus | Cicero | Dionysius | Apollodorus | Hyginus | Dictys | Clement | Suda | Tzetzes | ||

| Parentage | Tros | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Acallaris | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Callirhoe | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Laomedon | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Erichthonius | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Assaracus | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Dardanus | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Ilus | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Siblings | Ilus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Assaracus | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Cleopatra | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Cleomestra | ✓ | ||||||||||||

Mythology

Ganymede was abducted by Zeus from Mount Ida near Troy in Phrygia. Ganymede had been tending sheep, a rustic or humble pursuit characteristic of a hero's boyhood before his privileged status is revealed. Zeus either summoned an eagle or turned into an eagle himself to transport the youth to Mount Olympus.[20][lower-alpha 1]

On Olympus, Zeus had him granted eternal youth and immortality and the office of cupbearer to the gods, in place of his daughter Hebe who was relieved of her duties as cupbearer upon her marriage to Herakles. Alternatively, the Iliad presents Hebe (and at one instance, Hephaestus) as the cupbearer of the gods with Ganymede acting as Zeus’s personal cupbearer.[22][23] Edmund Veckenstedt associated Ganymede with the genesis of the intoxicating drink mead, which had a traditional origin in Phrygia.[24] In some literature such as the Aeneid, Hera, Zeus's wife, regards Ganymede as a rival for her husband's affection.[25] In some traditions, Zeus later put Ganymede in the sky as the constellation Aquarius (the "water-carrier" or "cup-carrier"), which is adjacent to Aquila (the Eagle).[26] The largest moon of the planet Jupiter (named after Zeus's Roman counterpart) was named Ganymede by the German astronomer Simon Marius.[27]

In the Iliad, Zeus is said to have compensated Ganymede's father Tros by the gift of fine horses, "the same that carry the immortals", delivered by the messenger god Hermes.[28] Tros was consoled that his son was now immortal and would be the cupbearer for the gods, a position of much distinction.

Plato accounts for the pederastic aspect of the myth by attributing its origin to Crete, where the social custom of paiderastía was supposed to have originated (see "Cretan pederasty").[29] Athenaeus recorded a version of the myth where Ganymede was abducted by the legendary King Minos to serve as his cupbearer instead of Zeus.[30] Some authors have equated this version of the myth to Cretan pederasty practices, as recorded by Strabo and Ephoros, that involved abduction of a youth by an older lover for a period of two months before the youth was able to re-enter society as a man.[30] Xenophon portrays Socrates as denying that Ganymede was the catamite of Zeus, instead asserting that the god loved him for his psychē, "mind" or "soul," giving the etymology of his name as ganu- "taking pleasure" and mēd- "mind." Xenophon's Socrates points out that Zeus did not grant any of his lovers immortality, but that he did grant immortality to Ganymede.[31]

In poetry, Ganymede became a symbol for the beautiful young male who attracted homosexual desire and love. He is not always portrayed as acquiescent, however, as in the Argonautica of Apollonius of Rhodes, Ganymede is furious at the god Eros for having cheated him at the game of chance played with knucklebones, and Aphrodite scolds her son for "cheating a beginner."[32] The Augustan poet Virgil portrays the abduction with pathos: the boy's aged tutors try in vain to draw him back to Earth, and his hounds bay uselessly at the sky.[33] The loyal hounds left calling after their abducted master is a frequent motif in visual depictions, and is referenced by Statius:

Here the Phrygian hunter is borne aloft on tawny wings, Gargara’s range sinks downwards as he rises, and Troy grows dim beneath him; sadly stand his comrades; vainly the hounds weary their throats with barking, pursue his shadow or bay at the clouds.[34]

In the arts

Ancient visual arts

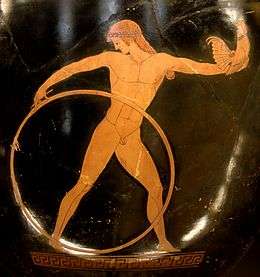

In 5th century Athens, the story of Ganymede became popular among vase-painters, which was suited to the all-male symposium.[36] Ganymede was usually depicted as a muscular young man, although Greek and Roman sculpture typically depicted his physique as less developed than athletes.[37]

One of the earliest depictions of Ganymede is a red-figure krater by the Berlin Painter in the Musée du Louvre.[38] Zeus pursues Ganymede on one side, while on the other side the youth runs away, rolling along a hoop while holding aloft a crowing cock. The Ganymede myth was treated in recognizable contemporary terms, illustrated with common behavior of homoerotic courtship rituals, as on a vase by the "Achilles Painter" where Ganymede also flees with a cock. Cocks were common gifts from older male suitors to younger men they were interested in romantically in 5th century Athens.[36] Leochares (ca. 350 B.C.E.), a Greek sculptor of Athens who was engaged with Scopas on the Mausoleum at Halicarnassus cast a lost bronze group of Ganymede and the Eagle, a work that was held remarkable for its ingenious composition.[36] It is apparently copied in a well-known marble group in the Vatican.[39] Such Hellenistic gravity-defying feats were influential in the sculpture of the Baroque.

Ganymede and Zeus in the guise of an eagle were a popular subject on Roman funerary monuments with at least 16 sarcophagi depicting this scene.[37]

Renaissance and Baroque

Ganymede was a major symbol of homosexual love in the visual and literary arts from the Renaissance to the Late Victorian era, where Antinous, the reported lover of the Roman Emperor Hadrian, became a more popular subject.[40]

In Shakespeare's As You Like It (1599), a comedy of mistaken identity in the magical setting of the Forest of Arden, Celia, dressed as a shepherdess, becomes "Aliena" (Latin "stranger", Ganymede's sister) and Rosalind, because she is "more than common tall", dresses up as a boy, Ganymede, a well-known image to the audience. She plays on her ambiguous charm to seduce Orlando, but also (involuntarily) the shepherdess Phoebe. Thus behind the conventions of Elizabethan theater in its original setting, the young boy playing the girl Rosalind dresses up as a boy and is then courted by another boy playing Phoebe. Ganymede also appears in the opening of Christopher Marlowe play Dido, Queene of Carthage, where his and Zeus’s affectionate banter is interrupted by an angry Hera.[41] In later Jacobean tragedy, Women Beware Women, Ganymede, Hebe, and Hymen briefly appear to serve as cupbearers to the court, one of which has been poisoned in an assassination attempt, although the plan goes awry.[42]

Allusions to Ganymede occur with some frequency in 17th century Spanish theater. In El castigo sin venganza (1631) by Lope de Vega, Federico, the son of the Duke of Mantua, rescues Casandra, his future step-mother, and the pair will later develop an incestuous relationship. To emphasize the non-normative relation, the work includes a long passage, possibly an ekphrasis derived from Italian art, in which Jupiter in the form of an eagle abducts Ganymede.[43] Two plays by Tirso de Molina, and in particular La purdencia en la mujer, include intriguing references to Ganymede. In this particular play, a Jewish doctor who seeks to poison the future king, carries a cup which is compared to Ganymede's.[44]

One of the earliest surviving non-ancient depictions of Ganymede is a woodcut from the first edition of Emblemata (ca. 1531), which shows the youth riding the eagle as opposed to being carried away, however, this composition is likely not typical, as an earlier composition by Michelangelo that survives only as sketches depicts Ganymede being carried.[45] Painter-architect Baldassare Peruzzi included a panel of The Rape of Ganymede in a ceiling at the Villa Farnesina, Rome, (ca 1509–1514), Ganymede's long blond hair and girlish pose make him identifiable at first glance, though he grasps the eagle's wing without resistance. In Antonio Allegri Correggio's Ganymede Abducted by the Eagle (Vienna) Ganymede's grasp is more intimate. Rubens' version portrays a young man. But when Rembrandt painted the Rape of Ganymede for a Dutch Calvinist patron in 1635, a dark eagle carries aloft a plump cherubic baby (Paintings Gallery, Dresden) who is bawling and urinating in fright.[46] In contrast, Johann Wilhelm Baur portrays a full-grown Ganymede confidently riding the eagle towards Olympus in Ganymede Triumphant (ca. 1640s).[45] A 1685 statue of Ganymede and Zeus entitled Ganymède Médicis by Pierre Laviron stands in the gardens of Versailles.

Examples of Ganymede in 18th century France have been studied by Michael Preston Worley.[47] The image of Ganymede was invariably that of a naive adolescent accompanied by an eagle and the homoerotic aspects of the legend were rarely dealt with. In fact, the story was often "heterosexualized." Moreover, the Neoplatonic interpretation of the myth, so common in the Italian Renaissance, in which the rape of Ganymede represented the ascent to spiritual perfection, seemed to be of no interest to Enlightenment philosophers and mythographers. Jean-Baptiste Marie Pierre, Charles-Joseph Natoire, Guillaume II Coustou, Pierre Julien, Jean-Baptiste Regnault and others contributed images of Ganymede to French art during this period.

The Rape of Ganymede (1611) by Rubens

The Rape of Ganymede (1611) by Rubens The Abduction of Ganymede (1635) by Rembrandt

The Abduction of Ganymede (1635) by Rembrandt.jpg) The Induction of Ganymede in Olympus (1768) by van Loo

The Induction of Ganymede in Olympus (1768) by van Loo Ganymède Médicis (1684-1685) by Pierre Laviron at Versailles.

Ganymède Médicis (1684-1685) by Pierre Laviron at Versailles.

Modern

_MRABASF_01.jpg)

- José Álvarez Cubero's sculpture of Ganymede, executed in Paris in 1804, brought the Spanish sculptor immediate recognition as one of the leading sculptors of his day.[48]

- Vollmer's Wörterbuch der Mythologie aller Völker,[49] (Stuttgart, 1874) illustrates "Ganymede" by an engraving of a "Roman relief," showing a seated bearded Zeus who holds the cup aside to draw a naked Ganymede into his embrace. That engraving however was nothing but a copy of Raphael Mengs's counterfeit Roman fresco, painted as a practical joke on the eighteenth-century art critic Johann Winckelmann who was growing desperate in his search for homoerotic Greek and Roman antiquities. This story is very briefly told by Goethe in his Italienische Reise.[50]

- At Chatsworth in the nineteenth century the bachelor Duke of Devonshire added to his sculpture gallery Adamo Tadolini's Neoclassic "Ganymede and the Eagle," in which a luxuriously reclining Ganymede, embraced by one wing, prepares to exchange a peck with the eagle. The delicate cup in his hand is made of gilt-bronze, lending an unsettling immediacy and realism to the white marble group.

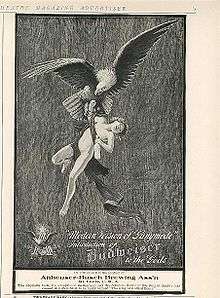

- In the early years of the twentieth century, the topos of Ganymede's abduction by Zeus was drafted into the service of commercial enterprise. Adapting an 1892 lithograph by Frank Kirchbach, the brewery of Anheuser-Busch launched in 1904 an ad campaign publicizing the successes of Budweiser beer. Collectibles featuring the graphics of the poster continued to be produced into the early 1990s.

- The poem “Ganymed” by Goethe was set to music by Franz Schubert in 1817; published in his Opus 19, no. 3 (D. 544). Also set by Hugo Wolf.

- The Portuguese sculptor António Fernandes de Sá represented the abduction of Ganymede in 1898. The sculpture can be found in Jardim da Cordoaria, in Porto (Portugal).

- In stories by P. G. Wodehouse, the Junior Ganymede is a servants' club, analogous to the Drones, to which Jeeves belongs. Wodehouse named it after Ganymede presumably in reference to his role of cup-bearer.

- Ganymede is a reluctant music fan in Kurtis Blow's 1980 song "Way Out West". After hours of rap by "The Stranger" (Kurtis), he eventually gets up to dance.

- American artist Henry Oliver Walker painted a mural in the Library of Congress in Washington D.C. circa 1900, depicting an adolescent, nude Ganymede on the back of an eagle.

- Ganymede and the god Dionysus make an appearance in Everworld VI: Fear the Fantastic, of K.A. Applegate's fantasy series Everworld. Ganymede is described as attracting both males and females.

My first thought, my first flash was that it was a beautiful woman.... The angel was beautiful, with a face dominated by immense, lustrous green eyes and framed by golden ringlets, and with a bow mouth and full lips and brilliant white teeth.

And only then, only after I had felt that first rush of improbable carnal lust, did it occur to me that this angel was a man.[51]

- In 1959 Robert Rauschenberg referenced the myth in one of his best-known works, Canyon and in another work, Pail for Ganymede. In "Canyon", a photo of Rauschenberg's son Christopher beautifully reiterates the infant portrayed by Rembrandt in the 17th century. A stuffed eagle emerges from the flat picture plane with a pillow tied to a piece of string very near his claw. The pillow also reflects upon the young boy's body and Rembrandt's painting.

- Ganymede is a reluctant son in W.H.Auden's poem of that name, but he adores the eagle which teaches him how to kill.

- Felice Picano's 1981 novel An Asian Minor reinvents the story of Ganymede.

- In the 2016 video game Overwatch, the character Bastion has a bird named Ganymede.

- A character in the Terra Ignota series by Ada Palmer is named Ganymede de la Trémoille

- The opening of Will Self's 2017 novel Phone refers to 'agents of Ganymede' (p.6) to explore caution within the homosexual community in previous decades.

Ancient sources

Ganymede is named by various ancient Greek and Roman authors:

- Homer – Iliad 5.265; Iliad 20.232;

- Homerica – The Little Iliad, Frag 7;

- Homeric Hymns – Hymn V, To Aphrodite, 203-217;

- Theognis – Fragments 1.1345;

- Pindar – Olympian Odes 1; 11;

- Euripides – Iphigenia at Aulis 1051;

- Plato – Phaedrus 255; Laws 636c

- Apollonios Rhodios – Argonautica 3.112f;

- ps-Apollodorus – Bibliotheke 2.104; 3.141;

- Strabo – Geography 13.1.11;

- Pausanias – Guide to Greece V.24.5; V.26.2-3;

- Diodorus Siculus – The Library of History 4.75.3;

- Hyginus

- Fabulae 89; 224; 271;

- Astronomica 2.16; 2.29;

- Ovid – Metamorphoses 10.152;

- Virgil – Aeneid 1.28; 5.252;

- Cicero – De Natura Deorum 1.40;

- Valerius Flaccus – Argonautica 2.414; 5.690;

- Statius

- Apuleius – The Golden Ass 6.15; 6.24;

- Quintus Smyrnaeus - Fall of Troy 8.427; 14.324;

- Nonnus – Dionysiaca 8.93; 10.258; 10.308; 12.39; 14.430; 15.279; 17.76; 19.158; 25.430; 27.241; 31.252; 33.74; 39.67; 47.98;

- Suda – Ilion; Minos;

Modern sources

![]()

Family tree

References

- "Ganymede". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- "Ganymedes". Dictionary.com Unabridged. Random House.

- Lattimore, Richard, trans. The Iliad of Homer. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1951.

- According to AMHER (2000), catamite, p. 291.

- "Plato: Laws". Perseus Digital Library. 636C. Retrieved 2020-03-13.CS1 maint: location (link)

- Diodorus Siculus, Bibliotheca historica 4.75.3-5

- Homer, Iliad 20.230-240

- Suda v.s. Minos

- Tzetzes on Lycophron, 29

- Scholiast on Homer's Iliad 20.231 who refers to Hellanicus as his authority

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca 3.12.2

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus, Antiquitates Romanae 1.62.2

- Dictys Cretensis, Trojan War Chronicle 4.22

- Cicero, Tusculanae Disputationes 1.65

- Euripides, Troad 822

- Tzetzes ad Lycophron 34

- Clement of Alexandria, Recognitions 22

- Hyginus, Fabulae 224

- Hyginus, Fabulae 271

- Virgil, Aeneid, 5.252

- Strabo. "Geography 13.1.11". Perseus Digital Library. Tufts University. Retrieved 19 March 2020.

- Homer, Iliad 20.230

- Combellack, Frederick M. (1987). "The lusis ek ths lecews". The American Journal of Philology. 108 (2): 202–219. doi:10.2307/294813. JSTOR 294813.

- Edmund Veckenstedt, Ganymedes, Libau, 1881.

- Virgil, Aeneid, 1.28

- Marshall, David Weston (2018). Ancient Skies: Constellation Mythology of the Greeks. New York, NY: The Countryman Press. pp. 45–46. ISBN 978-1682682111.

- Marius/Schlör, Mundus Iovialis, p. 78 f. (with misprint In for Io)

- The Achaean Diomedes is keen to capture the horses of Aeneas because "...they are of that stock wherefrom Zeus, whose voice is borne afar, gave to Tros recompense for his son Ganymedes, for that they were the best of all horses that are beneath the dawn and the sun.": Homer, Iliad 5.265ff.

- Plato, Laws 636D, as cited by Thomas Hubbard, Homosexuality in Greece and Rome, p252

- Koehl, Robert B. (1986). "The Chieftain Cup and a Minoan Rite of Passage". The Journal of Hellenic Studies. 106: 99–110. doi:10.2307/629645. JSTOR 629645.

- Xenophon, Symposium 8.29–30; Craig Williams, Roman Homosexuality (Oxford University Press, 1999, 2010), p. 153.

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 3.112

- Virgil, Aeneid 5.256–7.

- Statius, Thebaid 1.549.

- For the cockerel as an emblematic gift to the eromenos, see, for example, H.A. Shapiro, "Courtship scenes in Attic vase-painting", American Journal of Archaeology, 1981; the gift is "gender specific, and it is clear that the cock had significance as evocative of male potency", T.J. Figueira observes, in reviewing two recent works on Greek pederasty, in American Journal of Archaeology, 1981.

- Woodford, Susan (1993). The Trojan War in Ancient Art. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press. p. 39. ISBN 978-0801481642.

- Bartman, Elizabeth (2002). "Eros's Flame: Images of Sexy Boys in Roman Ideal Sculpture". Memoirs of the American Academy in Rome. Supplementary Volumes 1: 249–271. JSTOR 4238454.

- "www.louvre.fr".

- D'Souza, J.P. (1947). "The Story of Vasu Uparichara and Its Sumerian, Greek and Roman Parallels". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 10: 171–176. JSTOR 44137123.

- Waters, Sarah (1995). ""The Most Famous Fairy in History": Antinous and Homosexual Fantasy". Journal of the History of Sexuality. 6 (2): 194–230. JSTOR 3704122.

- Williams, Deanne (2006). "Dido, Queen of England". ELH. 73 (1): 31–59. doi:10.1353/elh.2006.0010. JSTOR 30030002.

- Levin, Richard A. (1997). "The Dark Color of a Cardinal's Discontentment: The Political Plot of "Women Beware Women"". Medieval & Renaissance Drama in England. 10: 201–217. JSTOR 24322350.

- Frederick A. de Armas, "From Mantua to Madrid: The License of Desire in Giulio Romano, Correggio and Lope de Vega’s El castigo sin venganza” Bulletin of the Comediantes59.2 (2008): 233-65.

- Felipe E. Rojas, "Representing An-'Other' Ganymede: The Multi-Faceted Character of Ismael in Tirso de Molina's La purdencia en la mujer (1634)," Bulletin of Hispanic Studies (2014): 347-64.

- Orgel, Stephen (2004). "Ganymede Agonistes". GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies. 10 (3): 485–501. doi:10.1215/10642684-10-3-485.

- Barfoot, C.C.; Todd, Richard. The Great Emporium : the Low Countries as cultural crossroads in the Renaissance and the eighteenth century. Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi B.V.

- Worley, "The Image of Ganymede in France, 1730–1820: The Survival of a Homoerotic Myth," Art Bulletin 76 (December 1994: 630–643).

-

- "Vollmer-mythologie.de". Vollmer-mythologie.de. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- "Textlog.de". Textlog.de. Retrieved 2014-01-22.

- Applegate, K. A., Everworld VI: Fear the Fantastic, p. 50.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ganymede. |

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article "Ganymede". |