Sexual orientation and gender identity in military service

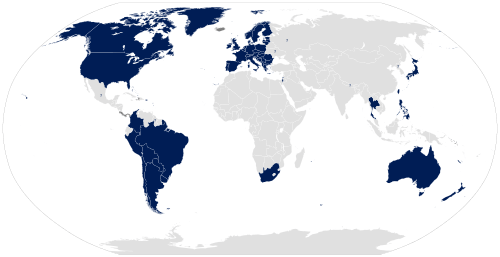

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) personnel are able to serve in the armed forces of some countries around the world: the vast majority of industrialized, Western countries, (including some Latin American countries such as Brazil and Chile,[1][2]) in addition to South Africa, and Israel.[3] The rights concerning intersex people are more vague.

|

| Part of a series on |

| Sexual orientation and gender identity in military service |

|---|

|

General articles

|

|

By country

|

|

Trans service by country

|

|

Intersex service by country

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT rights |

|---|

|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

Overview

|

|

Organizations

|

|

|

| Part of a series on |

| LGBT topics |

|---|

| lesbian ∙ gay ∙ bisexual ∙ transgender |

|

Issues

|

|

Academic fields and discourse |

|

|

This keeps pace with the latest global figures on acceptance of homosexuality, which suggest that acceptance of LGBTQ communities is becoming more widespread only in secular, affluent countries.[4]

However, an accepting policy toward gay and lesbian soldiers does not invariably guarantee that LGBTQ citizens are immune to discrimination in that particular society. Even in countries where LGBTQ persons are free to serve in the military, activists lament that there remains room for improvement. Israel, for example, a country that otherwise struggles to implement LGBTQ-positive social policy, nevertheless has a military well known for its broad acceptance of openly gay soldiers.[5][6]

History has seen societies that both embrace and shun openly gay service-members in the military. But more recently, the high-profile 2010 hearings on "Don't ask, don't tell" in the United States propelled the issue to the center of international attention. They also shed light both on the routine discrimination, violence, and hardship faced by LGBTQ-identified soldiers, as well as arguments for and against a ban on their service.[7]

LGBT Military Index

The LGBT Military Index is an index created by the Hague Centre for Strategic Studies that uses 19 indicative policies and best practices to rank over 100 countries on the inclusion of lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender service members in the armed forces. Countries with higher rankings, especially the ones at the top, stand out for their multiple concerted efforts to promote the inclusion of gay and lesbian soldiers. In many of them special support and advocacy organizations are present. By contrast, countries near the bottom of the index show the lack of aspiration to promote greater inclusion of the LGBT military personnel.[8][9][10]

History of sexual orientation in the military

Throughout history, there have been several cultures that have looked favorably on homosexual behavior in the military. Perhaps the most well-known example is found in ancient Greece and Rome. Homosexual behavior was encouraged among soldiers because it was thought to increase unit cohesiveness, morale and bravery.[11] The Sacred Band of Thebes was a military unit from 378 BCE which consisted of male lovers who were known for their effectiveness in battle.[12] Same-sex love was also prevalent among the Samurai class in Japan and was practiced between an adult and a younger apprentice.[13]

However, homosexual behavior has been considered a criminal offense according to civilian and military law in most countries throughout history. There are various accounts of trials and executions of members of the Knights Templar in the 14th century and British sailors during the Napoleonic wars for homosexuality.[14] Official bans on gays serving in the military first surfaced in the early 20th century. The U.S. introduced a ban in a revision of the Articles of War of 1916 and the UK first prohibited homosexuality in the Army and Air Force Acts in 1955.[15] However some nations, of which Sweden is the most well-known case, never introduced bans on homosexuality in the military, but issued recommendations on exempting homosexuals from military service.[16]

To regulate homosexuality in the U.S. military, physical exams and interviews were used to spot men with effeminate characteristics during recruitment. Many soldiers accused of homosexual behavior were discharged for being "sexual psychopaths", although the number of discharges greatly decreased during wartime efforts.[17]

The rationale for excluding gays and lesbians from serving in the military is often rooted in cultural norms and values and has changed over time. Originally, it was believed that gays were not physically able to serve effectively. The pervading argument during the 20th century focused more on military effectiveness. And finally, more recent justifications include the potential for conflict between heterosexual and homosexual service members and possible "heterosexual resentment and hostility."[18]

Many countries have since revised these policies and allow gays and lesbians to openly serve in the military (e.g. Israel in 1993 and the UK in 2000). There are currently more than 30 countries, including nearly all of the NATO members which allow gays and lesbians to serve and around 10 more countries that don't outwardly prohibit them from serving.[19]

The U.S. is one of the last more developed nations to overturn its ban on allowing gays, lesbians and bisexuals to openly serve in the military when it repealed the Don't Ask Don't Tell policy in 2010.[20]

Transgender military service

Like sexual orientation, policies regulating the service of transgender military personnel vary greatly by country. Based on data collected by the Hague Centre for Strategic Studies[21] seventeen countries currently allow transgender people to serve in their military. They are: Australia, Austria, Belgium, Bolivia, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Israel, Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Spain, Sweden, and the United Kingdom.[22]

While the US military's Don't Ask, Don't Tell policy was rescinded in 2011 allowing open service by gay, lesbian, and bisexual service members, transgender people are still barred from entering the US military.[23] This ban is effective via enlistment health screening regulations: "Current or history of psychosexual conditions (302), including but not limited to transsexualism, exhibitionism, transvestism, voyeurism, and other paraphilias."[24] Unlike Don't Ask, Don't Tell, this policy is not a law mandated by Congress, but an internal military policy. Despite this, studies suggest that the propensity of trans individuals to serve in the US military is as much as twice that as cisgender individuals. In the Harvard Kennedy School's 2013 National Transgender Discrimination Survey, 20% of transgender respondents reported having served in the armed forces, compared with 10% of cisgender respondents.[25][26]

American transgender veterans face institutional hardships, including the provision of medical care while in the armed services and after discharge stemming from their gender identity or expression. Transgender veterans may also face additional challenges, such as facing a higher rate of homelessness and home foreclosure, higher rates of losing jobs often directly stemming from their trans identity, and high rates of not being hired for specific jobs because of their gender identity.[26][27]

Intersex military service

The armed forces of Israel, the United States and Australia have employed intersex individuals depending on the nature of their conditions, but the guidelines are vague and seldom talked about.[28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39]

Discrimination in militaries without explicit limitations or welcoming

In the US army, six states (Texas, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma and West Virginia) initially refused to comply with Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel's order that gay spouses of National Guard members be given the same federal marriage benefits as heterosexual spouses, forcing couples to travel hours round trip to the nearest federal installation. Furthermore, some benefits offered on bases, like support services for relatives of deployed service members, could still be blocked.[40] This changed with a ruling by US Attorney General Loretta Lynch in the Supreme Court on 26 June 2015 which ruled that Federal marriage benefits would be made available to gay couples in all 50 US states.[41]

In 2013 legal changes were said to revert to practices to those before Don't Ask, Don't Tell, the National Defense Authorization Act contains language some claimed permitted individuals to continue discriminating against LGB soldiers.[42]

From June 30, 2016 to April 11, 2019, transgender personnel in the United States military were allowed to serve in their preferred gender upon completing transition. From January 1, 2018 to April 11, 2019, transgender individuals could enlist in the United States military under the condition of being stable for 18 months in their preferred or biological gender. On July 26, 2017, President Donald Trump announced on his Twitter page that transgender individuals would no longer be allowed "to serve in any capacity in the U.S. Military", effectively reinstating the ban.[43][44][45]

Further, throughout the US army, transgender people are still suffering from discrimination: they are prohibited from serving openly because of medical regulations that label them as mentally unstable.[46] On the contrary, in Australia, Canada, Germany, Israel, Italy, the Netherlands, and United Kingdom, as of 2010, when civil partnerships became legal in the respective countries, military family benefits followed the new laws, without discrimination.[47]

Fear of discrimination may prevent military service members to be open about their sexual orientation. In some cases, in Belgium, homosexual personnel have been transferred from their unit if they have been "too open with their sexuality." The Belgian military also continues to reserve the right to deny gay and lesbian personnel high-level security clearances, for fear they may be susceptible to blackmail.[48] In 1993, a study showed that in Canada, France, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands and Norway, the number of openly homosexual service members was small, representing only a minority of homosexuals usually serving. Serving openly may make their service less pleasant or impede their careers, even though there were no explicit limitations to serve. Thus service members who acknowledged their homosexuality were "appropriately" circumspect in their behavior while in military situations; i.e. they did not call attention to themselves.[49] Today, in the Danish army, LGBT military personnel refrain from being completely open about their homosexuality. Until training is completed and a solid employment is fixed they fear losing respect, authority and privileges, or in worse cases their job in the Danish army.[50] In 2010, the same updated study showed that in Australia, Canada, Germany, Israel, Italy and United Kingdom, no special treatment to prevent discrimination was in place in those armies, the issue is not specifically addressed, it is left to the leadership discretion. Commanders said that sexual harassment of women by men poses a far greater threat to unit performance than anything related to sexual orientation.[47]

On the other hand, the Dutch military directly addressed the issue of enduring discrimination, by forming the Homosexuality and Armed Forces Foundation, a trade union that continues to represent gay and lesbian personnel to the ministry of defense, for a more tolerant military culture. Although homosexuals in the Dutch military rarely experience any explicitly aggressive acts against them, signs of homophobia and cultural insensitivity are still present.[48]

Violence faced by LGBT people in the military

Physical, sexual, psychological (harassment, bullying) violence faced by LGBT is a fact of life for many LGBT identified persons. In an inherently violent environment, LGBT people may face violence unique to their community in the course of military service.

For instance, the Israeli Defense Force does not ask the sexual orientation of its soldiers, however half of the homosexual soldiers who serve in the IDF suffer from violence and homophobia. LGBT soldiers are often victims of verbal and physical violence and for the most part, commanders ignore the phenomenon.[51]

SAPRO, the organization responsible for the oversight of the Department of Defense (DoD - USA) sexual assault policy, produces the "Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Member (WGRA)": The 2012 report doesn't have any paragraph studying the specific situation of LGBT people. The study focuses on men and women. The specificity of the violence faced by LGBT people is not considered.[52]

In the Australian army, the problem is not known officially; only a few cases of harassment and discrimination involving gays and lesbians have been recorded. A researcher mentioned that "one would not want to be gay and in the military": Although there has been no major public scandal regarding harassment of gays, this does not mean that such behavior does not occur, but it has been under-studied. Generally, however, incidents of discrimination or harassment brought to the attention of commanders are handled appropriately, incidents in which peers who had made inappropriate remarks are disciplined by superiors promptly and without reservation.[53]

Being LGBT in the military

In the United States, despite policy changes allowing for open LGBQ military service and the provision of some benefits to same-sex military couples, cultures of homophobia and discrimination persist.[54]

Several academics have written on the effects on employees in non-military contexts concealing their sexual orientation in the workplace. Writers on military psychology have linked this work to the experiences of LGBQ military service personnel, asserting that these studies offer insights into the lives of open LGBQ soldiers and those who conceal their orientation.[55] Sexual orientation concealment and sexual orientation linked harassment are stressors for LGBT individuals that lead to negative experiences and deleterious job-related outcomes. Specifically, non-open LGBT persons are found to experience social isolation.[55][56] In particular these products of work related stress can affect military job performance, due to the high reliance on connection and support for the well-being of all service members.[55][57][58][59]

In the United States LGBQ soldiers are not required to disclose their sexual orientation, suggesting that some LGBQ service members may continue to conceal their sexual orientation.[60] Studies suggest this could have harmful effects for the individual. A 2013 study conducted at the University of Montana found that non-open LGB US veterans face significantly higher rates of depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, and alcohol or other substance abuse than their heterosexual counterparts. These veterans also reported facing significant challenges serving while concealing their sexual orientation; 69.3% of subjects in the study reported experiencing fear or anxiety as a result of concealing their sexual identity, and 60.5% reported that those experiences led to a more difficult time for the respondent than heterosexual colleagues. This study also concludes that 14.7% of LGB American veterans made serious attempts at suicide.[61] This rate of suicide attempts compares to another study of the entire American veteran community that found .0003% of American veterans attempt suicide.[62]

Evidence suggests that for LGB service members in the United States, the conditions of service and daily life have improved dramatically following the repeal of Don't Ask, Don't Tell. Soldiers who choose to come out experience feelings of liberation, and report that no longer having to hide their orientation allows them to focus on their jobs.[63] Support groups for LGB soldiers have also proliferated in the United States.[64]

Arguments for including openly LGBT people

Until recently, many countries banned gays and lesbians from serving openly in the armed forces. The reasons to enforce this ban included the potential negative impact on unit cohesion and privacy concerns. However, many studies commissioned to examine the effects on the military found that little evidence existed to support the discriminatory policy.[65] Moreover, when the bans were repealed in several countries including the UK, Canada, and Australia, no large scale issues arose as a result.[66]

In fact, several studies provide evidence that allowing gays and lesbians to openly serve in the armed forces can result in more positive work related outcomes. Firstly, discharging trained military personnel for their sexual orientation is costly and results in loss of talent. The total cost for such discharges in the U.S for violating the Don't Ask Don't Tell policy amounted to more than 290 million dollars.[67] Secondly, privacy for service members has actually increased in countries with inclusive policies and led to a decrease in harassment. Although, it is important to note that many gays and lesbians do not disclose their sexual orientation once the ban is repealed.[68] Finally, allowing gays to openly serve ends decades of discrimination in the military and can lead to a more highly qualified pool of recruits. For instance, the British military reduced its unfilled position gap by more than half after allowing gays to openly serve.[69] Therefore, more evidence exists now to support policies that allow gays and lesbians to openly serve in the military.

Arguments for not including openly LGBT people

The arguments against allowing openly gay servicemen and women in the military abound. While most research data have all but debunked traditional arguments in favor of policies like Don't Ask, Don't Tell, homosexuality is still perceived by most countries to be incompatible with military service.[70]

A recurrent argument for a ban on homosexuals in the military rests on the assumption that, in the face of potentially homosexual members of their unit, prospective recruits would shy away from military service. Based on an inconclusive study produced by the RAND Corporation in the run-up to the repeal of Don't Ask, Don't Tell, American military recruits were expected to decrease by as much as 7%.[71] However, this does not appear to have materialized.[72]

In a line of work that regularly demands that personnel be in close living quarters, allowing openly homosexual servicemen is argued to flout a fundamental tenet of military service: ensuring that soldiers remain undistracted from their mission. If gay men are allowed to shower with their fellow male soldiers, so goes the argument, this would, in effect, violate the "unique conditions" of military life by putting sexually compatible partners in close proximity, with potentially adverse effects on retention and morale of troops.[73] Testimony advanced during the hearings on Don't Ask, Don't Tell of 1993, with US Senator Sam Nunn and General Norman Schwarzkopf, Jr. recalled "instances where heterosexuals have been solicited to commit homosexual acts, and, even more traumatic emotionally, physically coerced to engage in such acts".[74]

Military historian Mackubin Thomas Owens conjectured in an Op-Ed for The Wall Street Journal that gay men and women would be partial to their lovers in the heat of battle. "Does a superior order his or her beloved into danger," Owens asks, "if he or she demonstrates favoritism, what is the consequence for unit morale and discipline? What happens when jealousy rears its head?" Owens echoes the fear that allowing gay soldiers would be deleterious to unit cohesion on the battlefield, arguing that concern for one's lover in a given unit could override any sense of loyalty to the unit as a whole, particularly in situations of life and death.[75]

Owens further asserts that homosexuality may be incompatible with military service because it undermines the very ethos of a military, that is, one of nonsexual "friendship, comradeship or brotherly love".[75]

Tony Perkins of the Family Research Council, a socially conservative advocacy organization, believes that allowing openly homosexual soldiers threatens the religious liberty of servicemen who disapprove of homosexuality for religious reasons.[76]

By country

References

- "Chile's National Military Announce a Milestone in Sexual Orientation". Archived from the original on 4 January 2015. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

- "Gay rights group lauds efforts to make Chilean military more inclusive". The Santiago Times. Archived from the original on 16 August 2014. Retrieved 13 August 2014.

- Frank, Nathaniel. "How Gay Soldiers Serve Openly Around the World". NPR. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "The Global Divide on Homosexuality Greater Acceptance in More Secular and Affluent Countries". Pew Research Center. 2013-06-04. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- Yaron, Oded (2013-12-12). "Israeli LGBTQ activists mobilize online after gay rights bill fails". Haaretz. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- Sherwood, Harriet (2012-06-13). "Israeli military accused of staging gay pride photo". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- Bacon, Perry (2010-05-28). "House votes to end 'don't ask, don't tell' policy". The Washington Post. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- Ed Pilkington (2014-02-20). "US ranks low in first-ever global index of LGBT inclusion in armed forces". The Guardian.

- "LGBT Military Index - News - HCSS Centre for Strategic Studies". HCSS Centre for Strategic Studies.

- "LGBT Military Index - Monitor". hcss.nl.

- A Brief History of Gays in the Military, Feb 2, 2010, Times, Retrieved 2013-11-15.

- Homosexuality in Greece and Rome , 2.14 Plutarch, Pelopidas 18-19

- Love of the Samurai: A Thousand Years of Japanese Homosexuality, Tsuneo Watanabe and Junʼichi Iwata, 1989.

- Brief History of Gays in the Military

- European Court of Human Rights Overturns British Ban on Gays in Military, Richard Kamm, Human Rights Brief 7, no. 3, 2000, p. 18-20

- Sundevall, Fia; Persson, Alma (2016). "LGBT in the Military: Policy Development in Sweden 1944–2014". Sexuality Research and Social Policy. 13 (2): 119–129. doi:10.1007/s13178-015-0217-6. PMC 4841839. PMID 27195050.

- Homosexuals in the U.S. Military: Open Integration and Combat Effectiveness, By Elizabeth Kier, International Security 23, no.2, MIT Press, 1998, p. 5-39

- "GAYS IN FOREIGN MILITARIES 2010: A GLOBAL PRIMER" (PDF). Palm Center. 2010.

- Countries Where Gays Do Serve Openly In The Military, May 25, 2011 Retrieved 2013-15-11

- 'Don't ask, don't tell' ban on openly gay troops overturned, Senate passes bill 65-31, Dec 18, 2010, Retrieved 2013-15-11

- Joshua Polchar et al., LGBT Military Personnel; A Strategic Vision for Inclusion (The Hague, the Netherlands: The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2014)

- Elders et al, "Medical Aspects of Transgender Military Service" Armed Forces & Society (2014) vol. 41 no. 2 pp 199-220

- Halloran, Liz (20 September 2011). "With Repeal Of 'Don't Ask, Don't Tell,' An Era Ends". National Public Radio. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "Medical Standards for Appointment, Enlistment, or Induction in the Military Services" (PDF). Department of Defense. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Harrison-Quintana, Jack; Jody L. Herman (2013). "Still Serving in Silence: Transgender Service Members and Veterans in the National Transgender Discrimination Survey" (PDF). LGBTQ Policy Journal. 3. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Brydum, Sunnivie (1 August 2013). "Trans Americans Twice As Likely to Serve in Military, Study Reveals". The Advocate. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- Srinivasan, Rajiv (November 11, 2013). "How to Really Honor Veterans: Extend Benefits to Transgender Vets". Time. Retrieved 17 November 2013.

- "Gender, Sexuality and Joining the Military". 2010-02-10.

- "The great hermaphrodites-in-the-military debate".

- "DADT: And then They Came for the Hermaphrodites".

- Marom, T.; Itskoviz, D.; Ostfeld, I. (2008). "Intersex patients in military service". Military Medicine. 173 (11): 1132–5. doi:10.7205/MILMED.173.11.1132. PMID 19055190.

- "Does VA distinguish between transsexual gender-confirmation surgery and intersex surgery?".

- "VHA Issues New Directive on Trans and Intersex Veteran Health Care".

- Danon, Limor Meoded (2015). "The Body/Secret Dynamic". SAGE Open. 5 (2): 215824401558037. doi:10.1177/2158244015580370.

- Marom, Tal; Itskoviz, David; Ostfeld, Ishay (2008). "Intersex Patients in Military Service". Military Medicine. 173 (11): 1132–1135. doi:10.7205/MILMED.173.11.1132. PMID 19055190.

- "Witch-hunts and surveillance: The hidden lives of LGBTI people in the military". 2017-04-25.

- "Celebrating 25 years of diversity in the armed forces". 2017-09-24.

- Serving in Silence?: Australian LGBT servicemen and women Foreword

- "What is gender X and why it matters to government and Defence". 2017-09-26.

- OPPEL Jr., Richard A. (2013-11-10). "Texas and 5 Other States Resist Processing Benefits for Gay Couples". The New York Times. Retrieved 2013-11-14.

- "US extends federal marriage benefits to gay couples in all states". Gay Star News. 2015-07-10. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- Dao, James (January 4, 2013). "How Defense Act Addresses Military Suicides and Issues of Conscience". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- "Trump bans transgender people in military". 2017-07-26. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- Bromwich, Jonah Engel (2017-07-26). "How U.S. Military Policy on Transgender Personnel Changed Under Obama". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- staff, Guardian; agencies (2019-04-13). "Trans troops return to era of 'don't ask, don't tell' as Trump policy takes effect". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved 2019-06-04.

- Grant, Jaime M. (2011-01-10). "Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey" (PDF). National Center for Transgender Equality, National Gay and Lesbian Task Force. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-09-08. Retrieved 2013-11-14.

- Rostker, Bernard D. (2010). "Sexual Orientation and U.S. Military Personnel Policy: An Update of RAND's 1993 Study" (PDF). RAND Corporation. Retrieved 2013-11-14.

- Bateman, Geoffrey W.; Assistant Director for the Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military, University of California, Santa Barbara (2004-06-23). "Military Culture: European". glbtq: An Encyclopedia of Gay, Lesbian, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer Culture. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2013-11-14.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- RAND Corporation report (1993). "Sexual Orientation and U.S. Military Personnel Policy: Options and Assessment" (PDF). RAND Corporation, National Defense Research Institute. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- Hansen, Hans Henrik (2010-01-20). "Seksuel orienteringsdiskriminering - et studie af seks homoseksuelle mænds oplevelser og erfaringer i det danske Forsvar". Nordic School of Public Health. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2013-11-10.

- Katz, Yaakov (2012-12-06). "Does viral IDF Gay Pride photo show full picture?". JPost.com. Retrieved 2013-11-28.

- "2012 Workplace and Gender Relations Survey of Active Duty Members" (PDF). Sexual Assault Prevention and Response Office - USA. 2013-03-15. Retrieved 2013-11-14.

- Belkin, Aaron; McNichol, Jason (2010-09-10). "The Effects Of Including Gay And Lesbian Soldiers In The Australian Defence Forces: Appraising The Evidence". Palm Center White Paper. Archived from the original on 2010-08-13. Retrieved 2013-11-14.

- Geidner, Chirs (November 24, 2013). "After Repeal Of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell," Pockets Of Difficulty For Equality". BuzzFeed. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- Moradi, Bonnie (2009). "Sexual Orientation Disclosure, Concealment, Harassment, and Military Cohesion: Perceptions of LGBT Military Veterans". Military Psychology. 21 (4): 513–533. doi:10.1080/08995600903206453.

- Croteau, J.M. (1996). "Research on the work experience of lesbian, gay, and bisexual people: An integrative review of methodology and findings". Journal of Vocational Behavior. 48 (2): 195–209. doi:10.1006/jvbe.1996.0018.

- Griffith, James (2002). "Multilevel analysis of cohesion's relation to stress, well-being, identification, disintegration, and perceived combat readiness". Military Psychology. 14 (3): 217–239. doi:10.1207/s15327876mp1403_3.

- Griffith, James; Mark Vaitkus (1999). "Relating cohesion to stress, strain, disintegration, and performance: An organizing framework". Military Psychology. 11: 27–55. doi:10.1207/s15327876mp1101_3.

- Sinclair, James; Venessa Tucker (2006). "Stress-CARE: An integrated model of individual differences in soldier performance under stress". Military Life: The Psychology of Serving in Peace and Combat. 1: 202–231.

- "Freedom to Serve: The Definitive Guide to LGBT Military Service" (PDF). OutServe SLDN. Service Members Legal Defense Network. July 27, 2011. p. 3. Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 August 2011. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- Cochran, Bryan; Kimberly Balsam; Annese Flentje; Carol A. Malte; Tracy Simpson (2013). "Mental Health Characteristics of Sexual Minority Veterans". Journal of Homosexuality. 60 (1–2): 419–435. doi:10.1080/00918369.2013.744932. PMID 23414280.

- Flanagan, Jack (March 1, 2013). "Closeted gay soldiers more likely to attempt suicide". Gay Star News. Retrieved 29 November 2013.

- Swarns, Rachel (November 16, 2012). "Out of the Closet and Into a Uniform". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Frosch, Dan (June 29, 2013). "In Support Groups for Gay Military Members, Plenty of Asking and Telling". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Herek, Gregory (2006). "Sexual Orientation and Military Service: Prospects for Organizational and Individual Change in the United States" (PDF). UC Davis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-06.

- "FOREIGN MILITARIES PRIMER 2010" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-05-25.

- "Lesbian, gay, and bisexual men and women in the US military: Updated estimates". The Williams Institute. 2010.

- , Gays in Foreign Militaries 2010: A Global Primer.

- U.S. allies say integrating gays in military was nonissue, May 20, 2010, Retrieved 2013-15-11

- Frank, Nathaniel. "How Gay Soldiers Serve Openly Around The World". NPR. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Sexual Orientation and US Military Personnel Policy" (PDF). RAND Corporation. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "One Year Out: An Assessment of DADT Repeal's Impact on Military Readiness" (PDF). Palm Center. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- "Readiness, Retention, Recruitment: Repeal of "Don't Ask, Don't Tell"". House Republicans. Archived from the original on 13 December 2012. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- Belkin, Aaron. "Don't Ask, Don't Tell: Is the Gay Ban Based on Military Necessity?" (PDF). Strategic Studies Institute. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- Owens, Mackubin Thomas (2 February 2010). "The Case Against Gays in the Military". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

- Perkins, Tony (2010-06-01). "My Take: Ending 'don't ask, don't tell' would undermine religious liberty". CNN. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

Sources

- Shilts, Randy (1994/1997/2005). Conduct Unbecoming: Gays and Lesbians in the US Military. ISBN 5-551-97352-2 / ISBN 0-312-34264-0.

Further reading

- Belkin, Aaron; et al. (2013). "Readiness and DADT Repeal: Has the New Policy of Open Service Undermined the Military?". Armed Forces & Society. 39 (4): 587–601. doi:10.1177/0095327x12466248.

- Belkin, Aaron; Levitt, Melissa (2001). "Homosexuality and the Israel Defense Forces: Did Lifting the Gay Ban Undermine Military Performance?". Armed Forces & Society. 27 (4): 541–565. doi:10.1177/0095327x0102700403.

- Burg, B. R. (2002) Gay Warriors: A Documentary History from the Ancient World to the Present (New York University Press, 2002)

- De Angelis, Karin, et al. (2013) "Sexuality in the military." in International Handbook on the Demography of Sexuality (Springer Netherlands, 2013) pp 363–381.

- Frank, Nathaniel, ed. (2010) Gays in foreign militaries 2010: A global primer online

- Frank, Nathaniel. (2013) "The President's Pleasant Surprise: How LGBT Advocates Ended Don't Ask, Don't Tell," Journal of homosexuality 60, no. 2-3 (2013): 159–213.

- Frank, Nathaniel. (2009) Unfriendly Fire: How the Gay Ban Undermines the Military and Weakens America

- Okros, Alan, and Denise Scott. (2014) "Gender Identity in the Canadian Forces A Review of Possible Impacts on Operational Effectiveness." Armed Forces & Society 0095327X14535371.

- Polchar, Joshua, et al. (2014) LGBT Military: A Strategic Vision for Inclusion (The Hague Centre for Strategic Studies, 2014)

External links

- The Palm Center, University of California, Santa Barbara.

- Center for Military Readiness, Livonia, MI, Non-profit educational organization focusing on traditionalist military personnel policy: see Center for Military Readiness

- Military Culture: European

- Center for the Study of Sexual Minorities in the Military of the University of California, Santa Barbara

- Proud2Serve.net: Information and Resources on the UK Armed Forces approach to homosexuality

- ArmyLGBT.org.uk: Website of the British Army's LGBT Employee Network

- Stonewall UK: Armed Forces

- Defence Gay and Lesbian Information Service - Australia

- OutServe, US Site for serving soldiers

- West Point LGBT Alumni

- Human Rights Watch report: Uniform Discrimination The Don't Ask, Don't Tell Policy of the U.S. Military

- Survivor bashing – bias-motivated hate crimes

- Blue Alliance – LGBT Alumni of the US Air Force Academy

- History of gay and lesbian discrimination in Canadian Military

- Thomasson v. Perry – The 1st "As Applied" challenge of Don't Ask, Don't Tell to reach the U.S. Supreme Court

- DEFGLIS is an organisation of Regular, Reserve and Civilian members of the Australian Defence Organisation who are gay, lesbian, bisexual, intersex and transgender (GLBIT) and allies.

- Watch Open Secrets, a National Film Board of Canada documentary on homosexuals in the military during World War II