Siren (mythology)

In Greek mythology, the Sirens (Greek singular: Σειρήν, Seirḗn; Greek plural: Σειρῆνες, Seirênes) were dangerous creatures, who lured nearby sailors with their enchanting music and singing voices to shipwreck on the rocky coast of their island. Roman poets placed them on some small islands called Sirenum scopuli. In some later, rationalized traditions, the literal geography of the "flowery" island of Anthemoessa, or Anthemusa,[1] is fixed: sometimes on Cape Pelorum and at others in the islands known as the Sirenuse, near Paestum, or in Capreae.[2] All such locations were surrounded by cliffs and rocks.

| |

| Grouping | Mythological |

|---|---|

| Country | Greece |

According to the Greek Neoplatonist philosopher Proclus, Plato said there were three kinds of sirens: the celestial, the generative, and the purificatory / cathartic. The first were under the government of Zeus, the second under that of Poseidon, and the third of Hades. When the soul is in heaven the sirens seek, by harmonic motion, to unite it to the divine life of the celestial host; and when in Hades, to conform the soul to eternal infernal regimen; but when on earth their only job to "produce generation, of which the sea is emblematic".[3]

Etymology

The etymology of the name is at present contested. Robert S. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek origin.[4] Others connect the name to σειρά (seirá "rope, cord") and εἴρω (eírō "to tie, join, fasten"), resulting in the meaning "binder, entangler",[5] i. e. one who binds or entangles through magic song. This could be connected to the famous scene of Odysseus being bound to the mast of his ship, in order to resist their song.[6]

Appearance

Sirens were believed to look like a combination of women and birds in various different forms. In early Greek art, Sirens were represented as birds with large women's heads, bird feathers and scaly feet. Later, they were represented as female figures with the legs of birds, with or without wings, playing a variety of musical instruments, especially harps and lyres.

The seventh-century Anglo-Latin catalogue Liber Monstrorum says that Sirens were women from their heads to their navels, and instead of legs they had fish tails.[7] The tenth-century Byzantine encyclopedia Suda says that from their chests up, Sirens had the form of sparrows, and below they were women or, alternatively, that they were little birds with women's faces.[8]

By the Middle Ages, the figure of the siren has transformed into the enduring mermaid figure.[9]

Originally, Sirens were shown to be male or female, but the male Siren disappeared from art around fifth century BC.[10]

The first-century Roman historian Pliny the Elder discounted Sirens as a pure fable, "although Dinon, the father of Clearchus, a celebrated writer, asserts that they exist in India, and that they charm men by their song, and, having first lulled them to sleep, tear them to pieces."[11] In his notebooks, Leonardo da Vinci wrote of the Siren, "The siren sings so sweetly that she lulls the mariners to sleep; then she climbs upon the ships and kills the sleeping mariners."

Family

Although a Sophocles fragment makes Phorcys their father,[12] when Sirens are named, they are usually as daughters of the river god Achelous,[13] with Terpsichore,[14] Melpomene,[15] Calliope[16] or Sterope. In Euripides's play, Helen (167), Helen in her anguish calls upon "Winged maidens, daughters of the Earth (Chthon)." Although they lured mariners, the Greeks portrayed the Sirens in their "meadow starred with flowers" and not as sea deities. Roman writers linked the Sirens more closely to the sea, as daughters of Phorcys.[17] Sirens are found in many Greek stories, notably in Homer's Odyssey.

List of Sirens

_01.jpg)

Their number is variously reported as from two to eight.[18] In the Odyssey, Homer says nothing of their origin or names, but gives the number of the Sirens as two.[19] Later writers mention both their names and number: some state that there were three, Peisinoe, Aglaope and Thelxiepeia[20] or Parthenope, Ligeia, and Leucosia;[21] Apollonius followed Hesiod gives their names as Thelxinoe, Molpe, and Aglaophonos;[22] Suidas gives their names as Thelxiepeia, Peisinoe, and Ligeia;[23] Hyginus gives the number of the Sirens as four: Teles, Raidne, Molpe, and Thelxiope;[24][25] Eustathius[26] states that they were two, Aglaopheme and Thelxiepeia; an ancient vase painting attests the two names as Himerope and Thelxiepeia. Their individual names are variously rendered in the later sources as Thelxiepeia/Thelxiope/Thelxinoe, Molpe, Himerope, Aglaophonos/Aglaope/Aglaopheme, Pisinoe/Peisinoë/Peisithoe, Parthenope, Ligeia, Leucosia, Raidne, and Teles.[27][28][29][30]

- Aglaopheme (Αγλαοφήμη), Aglaophonos (Αγλαόφωνος), or Aglaope (Αγλαόπη), all to be translated as "with lambent voice"),[31] attested as a daughter of Achelous and Melpomene.[32]

- Leucosia (Λευκωσία): Her name was given to the island opposite to the Sirens' cape.[33] Her body was found on the shore of Poseidonia.[34]

- Ligeia (Λιγεία): She was found ashore of Terina in Bruttium (modern Calabria).[35]

- Molpe (Μολπή), another daughter of Achelous and Melpomene.[36]

- Parthenope (Παρθενόπη): Her tomb was presented in Naples and called "constraction of sirens".[37]

- Peisinoe (Πεισινόη) or Peisithoe (Πεισιθόη), daughter of Achelous and Melpomene.[32]

- Thelxiepeia (Θελξιέπεια) or Thelxiope (Θελξιόπη) "eye pleasing"), daughter of Achelous and Melpomene.[32][36]

| Relation | Names | Sources | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hesiod | Homer | Sophocles | (Sch. on) Apollonius | Lycophron | Strabo | Apollodorus | Hyginus | Servius | Eustathius | Suidas | Tzetzes | Vase Painting | Euripides | ||

| Parentage | Chthon | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Achelous and Terpsichore | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Achelous and Melpomene | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Achelous and Sterope | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Achelous and Calliope | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Phorcys | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Number | 2 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| 3 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| 4 | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Individual Names | Thelxinoe or Thelxiope | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Thelxiepia | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Thelxiepe | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Thelxiepeia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Aglaophonus | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Aglaope | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Aglaopheme | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Molpe | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Aglaonoe | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Parthenope | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Leucosia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Ligeia | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Peisinoe or Pisinoe | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Himerope | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

Mythology

Demeter

According to Ovid (43 BC–17 AD), the Sirens were the companions of young Persephone.[38] Demeter gave them wings to search for Persephone when she was abducted by Hades. However, the Fabulae of Hyginus (64 BC–17 AD) has Demeter cursing the Sirens for failing to intervene in the abduction of Persephone. According to Hyginus, sirens were fated to live only until the mortals who heard their songs were able to pass by them.[39]

The Muses

It is also said that Hera, queen of the gods, persuaded the Sirens to enter a singing contest with the Muses. The Muses won the competition and then plucked out all of the Sirens' feathers and made crowns out of them.[40] Out of their anguish from losing the competition, writes Stephanus of Byzantium, the Sirens turned white and fell into the sea at Aptera ("featherless"), where they formed the islands in the bay that were called Leukai ("the white ones", modern Souda).[41]

Argonautica

In the Argonautica (third century BC), Jason had been warned by Chiron that Orpheus would be necessary in his journey.[42] When Orpheus heard their voices, he drew out his lyre and played his music more beautifully than they, drowning out their voices. One of the crew, however, the sharp-eared hero Butes, heard the song and leapt into the sea, but he was caught up and carried safely away by the goddess Aphrodite.

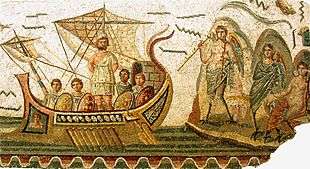

Odyssey

.jpg)

Odysseus was curious as to what the Sirens sang to him, and so, on the advice of Circe, he had all of his sailors plug their ears with beeswax and tie him to the mast. He ordered his men to leave him tied tightly to the mast, no matter how much he would beg. When he heard their beautiful song, he ordered the sailors to untie him but they bound him tighter. When they had passed out of earshot, Odysseus demonstrated with his frowns to be released.[43] Some post-Homeric authors state that the Sirens were fated to die if someone heard their singing and escaped them, and that after Odysseus passed by they therefore flung themselves into the water and perished.[44]

Sirens and death

%2C_f.47v_-_BL_Harley_MS_4751.jpg)

Statues of Sirens in a funerary context are attested since the classical era, in mainland Greece, as well as Asia Minor and Magna Graecia. The so-called "Siren of Canosa"—Canosa di Puglia is a site in Apulia that was part of Magna Graecia—was said to accompany the dead among grave goods in a burial. She appeared to have some psychopomp characteristics, guiding the dead on the after-life journey. The cast terracotta figure bears traces of its original white pigment. The woman bears the feet, wings and tail of a bird. The sculpture is conserved in the National Archaeological Museum of Spain, in Madrid. The Sirens were called the Muses of the lower world, classical scholar Walter Copland Perry (1814–1911) observed: "Their song, though irresistibly sweet, was no less sad than sweet, and lapped both body and soul in a fatal lethargy, the forerunner of death and corruption."[45] Their song is continually calling on Persephone. The term "siren song" refers to an appeal that is hard to resist but that, if heeded, will lead to a bad conclusion. Later writers have implied that the Sirens were cannibals, based on Circe's description of them "lolling there in their meadow, round them heaps of corpses rotting away, rags of skin shriveling on their bones."[46] As linguist Jane Ellen Harrison (1850–1928) notes of "The Ker as siren": "It is strange and beautiful that Homer should make the Sirens appeal to the spirit, not to the flesh."[47] The siren song is a promise to Odysseus of mantic truths; with a false promise that he will live to tell them, they sing,

Once he hears to his heart's content, sails on, a wiser man.

We know all the pains that the Greeks and Trojans once endured

on the spreading plain of Troy when the gods willed it so—

all that comes to pass on the fertile earth, we know it all![48]

"They are mantic creatures like the Sphinx with whom they have much in common, knowing both the past and the future", Harrison observed. "Their song takes effect at midday, in a windless calm. The end of that song is death."[49] That the sailors' flesh is rotting away, suggests it has not been eaten. It has been suggested that, with their feathers stolen, their divine nature kept them alive, but unable to provide food for their visitors, who starved to death by refusing to leave.[50]

Christian belief and modern reception

By the fourth century, when pagan beliefs were overtaken by Christianity, the belief in literal sirens was discouraged. Although Saint Jerome, who produced the Latin Vulgate version of the bible, used the word sirens to translate Hebrew tannīm ("jackals") in Isaiah 13:22, and also to translate a word for "owls" in Jeremiah 50:39, this was explained by Ambrose to be a mere symbol or allegory for worldly temptations, and not an endorsement of the Greek myth.[51]

The Early Christian euhemerist interpretation of mythologized human beings received a long-lasting boost from Isidore's Etymologiae:

They [the Greeks] imagine that "there were three Sirens, part virgins, part birds," with wings and claws. "One of them sang, another played the flute, the third the lyre. They drew sailors, decoyed by song, to shipwreck. According to the truth, however, they were prostitutes who led travelers down to poverty and were said to impose shipwreck on them." They had wings and claws because Love flies and wounds. They are said to have stayed in the waves because a wave created Venus.[52]

By the time of the Renaissance female court musicians known as courtesans filled the role of an unmarried companion and musical performances by unmarried women could be seen as immoral. Seen as a creature who could control a man's reason, female singers became associated with the mythological figure of the siren, who usually took a half-human, half-animal form somewhere on the cusp between nature and culture.[53]

Sirens continued to be used as a symbol for the dangerous temptation embodied by women regularly throughout Christian art of the medieval era; however, in the 17th century, some Jesuit writers began to assert their actual existence, including Cornelius a Lapide, who said of woman, "her glance is that of the fabled basilisk, her voice a siren's voice—with her voice she enchants, with her beauty she deprives of reason—voice and sight alike deal destruction and death."[54] Antonio de Lorea also argued for their existence, and Athanasius Kircher argued that compartments must have been built for them aboard Noah's Ark.[55]

Charles Burney expounded c. 1789, in A General History of Music: "The name, according to Bochart, who derives it from the Phoenician, implies a songstress. Hence it is probable, that in ancient times there may have been excellent singers, but of corrupt morals, on the coast of Sicily, who by seducing voyagers, gave rise to this fable."[56] John Lemprière in his Classical Dictionary (1827) wrote, "Some suppose that the Sirens were a number of lascivious women in Sicily, who prostituted themselves to strangers, and made them forget their pursuits while drowned in unlawful pleasures. The etymology of Bochart, who deduces the name from a Phoenician term denoting a songstress, favors the explanation given of the fable by Damm.[57] This distinguished critic makes the Sirens to have been excellent singers, and divesting the fables respecting them of all their terrific features, he supposes that by the charms of music and song they detained travellers, and made them altogether forgetful of their native land."[58]

Other cultures

The theme of perilous mythical female creatures seeking to seduce men with their beautiful singing is paralleled in the Danish medieval ballad known as "Elvehøj", in which the singers are elves. The ballad is also conserved in a Swedish version. A modern literary appropriation of the myth is to be seen in Clemens Brentano's Lore Lay ballad, published in his novel Godwi oder Das steinerne Bild der Mutter (1801).

In the folklore of some modern cultures, the concept of the siren has been assimilated to that of the mermaid. For example, the French word for mermaid is sirène, and similarly in certain other European languages.

Emily Wilson, the first woman to translate the Odyssey into English, pointed out that "the Sirens in Homer aren't sexy. e.g. we learn nothing even about their hair—in contrast to other divine temptresses. The seduction they offer is cognitive: they claim to know everything about the war in Troy, and everything on earth. They tell the names of pain."[59]

In music

Rolf Riehm composed an opera based on the myth, Sirenen – Bilder des Begehrens und des Vernichtens (Sirens – Images of Desire and Destruction) which premiered at the Oper Frankfurt in 2014. Susumu Hirasawa composed an album named Siren, which contains a track that is also named Siren. Darren Hayes wrote a song called “The Sirens Call” that was included on the 2011 album Secret Codes and Battleships.

In the hit video game, Ace Combat 7: Skies Unknown, during a combat mission over the ocean (Mission 11: ‘Fleet Destruction), a song in the game’s official soundtrack is titled: “Siren’s Song”. It contains an angelic, presumably all-female choir, similar to the Greek accounts of sirens.

Honours

Siren Lake in Antarctica is named after the mythological creature.

See also

References

- "We must steer clear of the Sirens, their enchanting song, their meadow starred with flowers" is Robert Fagles's rendering of Odyssey 12.158–9.

- Strabo i. 22; Eustathius of Thessalonica's Homeric commentaries §1709; Servius I.e.

- Brewer, E.Cobham (1883). Brewer's Dictionary of Phrase and Fable. London: Odham Press Limited. pp. 1003 f.

- Robert S. P. Beekes, Etymological Dictionary of Greek, Brill, 2009, p. 1316 f.

- Cf. the entry in the Wiktionary and the entry in the Online Etymology Dictionary.

- Homer, Odyssey, book 12.

- Orchard, Andy. "Etext: Liber monstrorum (fr the Beowulf Manuscript)". members.shaw.ca. Archived from the original on 2005-01-18.

- "Suda on-line". Archived from the original on 2015-09-24. Retrieved 2010-01-30.

- Mittman, Asa Simon; Dendle, Peter J (2016). The Ashgate research companion to monsters and the monstrous. London: Routledge. p. 352. ISBN 9781351894326. OCLC 1021205658.

- "CU Classics – Greek Vase Exhibit – Essays – Sirens". www.colorado.edu. Archived from the original on 2016-06-25. Retrieved 2017-10-20.

- Pliny the Elder, Natural History X, 70.

- Sophocles, fragment 861; Fowler, p. 31; Plutarch, Quaestiones Convivales – Symposiacs, Moralia.

- Ovid XIV, 88.

- Nonnus, Dionysiaca 13.309; John Tzetzes, Chiliades, 1.14, line 338.

- John Tzetzes, Chiliades, 1.14, line 339.

- Servius, Commentary on the Aeneid of Vergil, Book 5, 864.

- Virgil, V.846.

- Page, Michael; Ingpen, Robert (1987). Encyclopedia of Things That Never Were. New York: Viking Penguin Inc. p. 211. ISBN 0-670-81607-8.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - Odyssey 12.52

- Tzetzes, ad Lycophron 7l2; Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca E7. 18

- Eustathius, loc. cit.; Strabo v. §246, 252 commentary on Virgil's Georgics iv. 562

- Scholiast on Homer's Odyssey 12. 168, trans. Evelyn-White

- Suidas s.v. Seirenas

- Fabulae, praefat. p. 30, ed. Bunte

- Apollodorus. Apollodorus: The Library, with an English Translation by Sir James George FrĜĝĦazer, F.B.A., F.R.S. in II Volumes, 1921.

- Eustathius Commentaries §1709

- Linda Phyllis Austern, Inna Naroditskaya, Music of the Sirens, Indiana University Press, 2006, p.18

- William Hansen, William F. Hansen, Classical Mythology: A Guide to the Mythical World of the Greeks and Romans, Oxford University Press, 2005, p.307

- Ken Dowden, Niall Livingstone, A Companion to Greek Mythology, Wiley-Blackwell, 2011, p.353

- Mike Dixon-Kennedy, Encyclopedia of Greco-Roman Mythology, ABC-Clio, 1998, p.281

- Hesiod, The Catalogue of Women 27.

- Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheca VII, 18.

- Strabo, Geographica VI, 1.1.

- Lycophron, Alexandra 720.

- Lycophron, Alexandra 724.

- Hyginus, The myths, Introduction 30.

- Lycophron, Alexandra 716.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses V, 551.

- Pseudo-Hyginus, Fabulae 141 (trans. Grant).

- Lemprière 768.

- Caroline M. Galt, "A marble fragment at Mount Holyoke College from the Cretan city of Aptera", Art and Archaeology 6 (1920:150).

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica IV, 891–919.

- Odyssey XII, 39.

- Hyginus, Fabulae 141; Lycophron, Alexandra 712 ff.

- Perry, "The sirens in ancient literature and art", in The Nineteenth Century, reprinted in Choice Literature: a monthly magazine (New York) 2 (September–December 1883:163).

- Odyssey 12.45–6, Fagles' translation.

- Harrison 198

- Odyssey 12.188–91, Fagles' translation.

- Harrison, 199.

- Liner notes to Fresh Aire VI by Jim Shey, Classics Department, University of Wisconsin

- Ambrose, Exposition of the Christian Faith, Book 3, chap. 1, 4.

- Grant, Robert McQueen (1999). Early Christians and Animals. London: Routledge, 120. Translation of Isidore, Etymologiae (c. 600–636 AD), Book 11, chap. 3 ("Portents"), 30.

- Dunbar, Julie C. (2011). Women, Music, Culture. Routledge. p. 70. ISBN 978-1351857451. Retrieved 9 August 2019.

- Longworth, T. Clifton, and Paul Tice (2003). A Survey of Sex & Celibracy in Religion. San Diego: The Book Tree, 61. Originally published as The Devil a Monk Would Be: A Survey of Sex & Celibacy in Religion (1945).

- Carlson, Patricia Ann (ed.) (1986). Literature and Lore of the Sea. Amsterdam: Editions Rodopi, 270.

- Austern, Linda Phyllis, and Inna Naroditskaya (eds.) (2006). Music of the Sirens. Bloomington, IN: University of Indiana Press, 72.

- Damm, perhaps Mythologie der Griechen und Römer (ed. Leveiow). Berlin, 1820.

- Lemprière 768. Brackets in the original.

- "The Sirens In 'The Odyssey' Are Actually Way Cooler — And Creepier — Than You Thought". Bustle. Retrieved 2019-07-28.

Bibliography

- Fowler, R. L. (2013), Early Greek Mythography: Volume 2: Commentary, Oxford University Press, 2013. ISBN 978-0198147411.

- Harrison, Jane Ellen (1922) (3rd ed.) Prolegomena to the Study of Greek Religion. London: C.J. Clay and Sons.

- Homer, The Odyssey

- Lemprière, John (1827) (6th ed.). A Classical Dictionary;.... New York: Evert Duyckinck, Collins & Co., Collins & Hannay, G. & C. Carvill, and O. A. Roorbach.as mentioned in the scriptures

- Sophocles, Fragments, Edited and translated by Hugh Lloyd-Jones, Loeb Classical Library No. 483. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-674-99532-1. Online version at Harvard University Press.

Further reading

- Siegfried de Rachewiltz, De Sirenibus: An Inquiry into Sirens from Homer to Shakespeare, 1987: chs: "Some notes on posthomeric sirens; Christian sirens; Boccaccio's siren and her legacy; The Sirens' mirror; The siren as emblem the emblem as siren; Shakespeare's siren tears; brief survey of siren scholarship; the siren in folklore; bibliography"

- "Siren's Lament", a story based around one writer's perception of sirens. Though most lore in the story does not match up with lore we associate with the wide onlook of sirens, it does contain useful information.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sirens. |

- Theoi Project, Seirenes the Sirens in classical literature and art

- The Suda (Byzantine Encyclopedia) on the Sirens

- A Mythological Reference by G. Rodney Avant