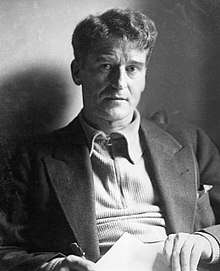

Ernie O'Malley

Ernie O'Malley (Irish: Earnán Ó Maille; born Ernest Bernard Malley; 26 May 1897 – 25 March 1957[1]) was an Irish Republican Army (IRA) officer during the Irish War of Independence and a commander of the anti-Treaty IRA during the Irish Civil War. He wrote three books, On Another Man's Wound, The Singing Flame, and Raids and Rallies. The first describes his early life and role in the War of Independence, while the second covers the Civil War.

Ernie O'Malley | |

|---|---|

| |

| Teachta Dála | |

| In office 27 August 1923 – 9 June 1927 | |

| Constituency | Dublin North |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Ernest Bernard Malley 26 May 1897 Castlebar, County Mayo, Ireland |

| Died | 25 March 1957 (aged 59) Howth, County Dublin, Ireland |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Irish Republican Army (1919–1922) Anti-Treaty IRA |

| Years of service | 1917–1923 |

| Battles/wars | Irish War of Independence Irish Civil War |

Early life

Born Ernest Bernard Malley, in Castlebar, County Mayo, on 26 May 1897. He was born into a lower-middle class Roman Catholic family and was the second of eleven children. His father, Luke Malley, was a solicitor's clerk with conservative Irish nationalist politics; he supported the Irish Parliamentary Party. His mother was Marion Malley (nee Kearney). The Malley family lived opposite a RIC barracks, and Ernie later noted the family's cordial relations with the RIC, saying that policemen would nod in courtesy when his father walked by. Ernie's first cousin, Gilbert Laithwaite, would become the British ambassador to Ireland in the 1950s.[2][3][4][5][6]

The Malleys moved to Dublin when Ernie was still a child and the 1911 census lists them living at 7 Iona Drive, Glasnevin.[7] His older brother, Frank, joined the Army at the outbreak of World War I.[5] O'Malley was studying medicine at University College Dublin in 1916 when the Easter Rising convulsed the city, and he was almost persuaded by some unionist friends to join them in defending Trinity College, Dublin from the rebels should they attempt to take it. After some thought, he decided his sympathies were with the rebels and he and a friend took some shots at British troops with a borrowed Mauser rifle during the fighting, provided by the Gaelic League.[5] He joined F Company, 1st battalion, Dublin Brigade, because its base was north of the Liffey. From only 12 men the company grew to 60 during 1916. Collins, De Valera, and O'Hegarty visited the Drill Hall hidden at 25 Parnell Square.[8]

IRA career

War of Independence

After the Easter Rising, O'Malley became deeply involved in Irish republican activism, a fact he had to hide from his family, who had close ties to the establishment. In 1917, he joined the Irish Volunteers and also Conradh na Gaeilge. During the Westmoreland Street riots, he stole a policeman's baton, and scarpered to the safety of the Fairview slums.

He left his studies and worked as a full-time organiser for the IRA from 1918 onward: work that brought him to almost every corner of Ireland.[5] On one occasion he attended a semi-public meeting of the Ulster Volunteer Force in County Tyrone for intelligence gathering, lamenting that such able men were opposed to his ideals.

GHQ sent O'Malley to Assistant chief of staff, Dick Mulcahy at Dungannon. He was appointed 2nd Lieutenant of the Coalisland district. Sinn Féin opposed conscription in principle, organising a mass boycott the Dublin government's policy. O'Malley was on the run in Tullamore where he first met Austin Stack and Darrell Figgis.

At Philipstown he was stopped by RIC, and went to draw on a concealed gun. From Athlone, where he tried to seize the magazine fort, he was sent to south Roscommon. There the police caught up with him and Brig. Brennan in the corner shop at Ballintubber. Escaping, he was crossing a bridge at the River Suck, Galway when the RIC fired and wounded, the fleeing suspect. He crossed again to Roscommon and went to ground in the mountains. Espying on FM Lord French at Rockingham House was hazardous; it was very dangerous for the IRA, in the vicinity of Carrick.[9] Night drilling continued in near silence behind village school houses, but the secret organising continued regardless.

Although officially attached to IRA GHQ, O'Malley was tasked as a training officer for rural IRA units, which involved IRA operations throughout the country once the war got under way.[5] In February 1920, Eoin O'Duffy and O'Malley led an IRA attack on the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) barracks in Ballytrain, County Monaghan, and were successful in taking it. This was the first capture of an RIC barracks in the war.[10]

In September, O'Malley and Liam Lynch led 2nd County Cork Brigade in the only capture of a British Army barracks of the conflict, in Mallow. They left with a haul of rifles, two Hotchkiss machine-guns and ammunition. In retaliation, several main street premises were subsequently torched by the British Army, including the town hall. The soldiers were finally brought under control by members of the Auxiliary Division of the RIC.

He was captured by the British at Kilkenny in December 1920, found in possession of a handgun. Much to his disgust, he had failed to destroy some notes, which contained the names of members of the 7th West Kilkenny Brigade, all of whom were subsequently arrested. At his arrest he gave his name as Bernard Stewart. Having been badly beaten during his interrogation at Dublin Castle and in severe danger of execution, he escaped from Kilmainham Gaol on 21 February 1921 along with IRA men Frank Teeling and Simon Donnelly, with the aid of a soldier who was also an Irish republican.[5] O'Malley was placed in command of the IRA's Second Southern Division in Munster, and for operations in Limerick, Kilkenny and Tipperary.[5]

Civil War

O'Malley objected to the Anglo-Irish Treaty that formally ended the "Tan War" (the term by which he and many other anti-Treaty Republicans preferred to refer to the War of Independence), opposing any settlement that fell short of an independent Irish Republic, particularly one backed up by British threats of restarting hostilities. He was one of the anti-Treaty IRA officers who occupied the Four Courts in Dublin, an event that helped to spark the Irish Civil War. O'Malley was appointed assistant chief of staff in the anti-Treaty forces.[11]

O'Malley surrendered to the Free State Army after the Battle of Dublin but escaped captivity and travelled via the Wicklow Mountains to Blessington then County Wexford and finally County Carlow.[5] This was probably fortunate for him, as four of the other Four Courts leaders were later executed. Thereafter, he was appointed Commander of the anti-Treaty forces in the provinces of Ulster and Leinster, and lived a clandestine existence in Dublin.[11]

In August 1922 O'Malley, Peadar O'Donnell and Joe McKelvey became supporters of Liam Mellows proposed 10 Point Programme for the Anti-Treaty IRA, which would have seen them adopt Communistic policies in an attempt to secure support from left-wing elements in Ireland, in contrast with the support base for the Treaty which skewed conservative. The programme was put before a vote of the Anti-Treaty IRA's executive but ultimately was defeated.[11]

In October 1922, he went to Dundalk and met with Frank Aiken (commander of the Fourth Northern Division of the Irish Republican Army) and Padraig Quinn (quartermaster-general) to review plans for an attack to free IRA soldiers from Dundalk jail. While Aiken's men did manage to free the prisoners, they were unable to hold Dundalk and dispersed after the operation was over. This type of incident is reflective of O'Malley's frustration at the defensive strategy of Liam Lynch, chief of staff of the anti-Treaty forces, which allowed the "Free Staters" (the Irish Free State Army) to build up their strength in preparation for a gradual take-over of areas of the country dominated by the "Irregulars". O'Malley expressed the view in his memoir, The Singing Flame, that the anti-Treaty side needed to use conventional warfare, as opposed to guerrilla warfare, if they were to win the war.

O'Malley was captured again after a shoot-out with Free State soldiers at the family home of Nell Humphreys at 26 Ailesbury Rd, in the Ballsbridge area of Dublin city on 4 November 1922.[5] O'Malley was severely wounded in the incident, being hit over twenty times (three bullets remained lodged in his back for the remainder of his life). A Free State soldier was also killed in the gun fight.[5] Anno O'Rahilly who lived at the house was accidentally shot by O'Malley during the raid.[12]

By the time O'Malley recovered from his wounds, the Civil War was over and he was transferred to Mountjoy Prison. During this period of imprisonment, he went on hunger strike for forty-one days, in protest at the continued detention of IRA prisoners after the war. During this time he was elected as a Sinn Féin Teachta Dála (TD) for Dublin North at the 1923 general election.[13] He did not contest the June 1927 general election.[14] He was one of the last republican prisoners to be released following the end of hostilities.

Subsequent literary life

O'Malley returned to University College Dublin to continue his medical studies in 1926 where he was heavily involved in the university hillwalking club, and its Literary and Historical societies, but he left Ireland in 1928 without graduating. In 1928, he toured the USA on behalf of Éamon de Valera raising funds for the establishment of the new Irish Republican newspaper, The Irish Press.

He spent the next few years travelling throughout the United States before arriving in Taos, New Mexico in 1930, where he lived among the Native Americans for a time and began work on his account of the manuscript that would later become On Another Man's Wound. He fell in with Mabel Dodge Luhan and her artistic circle that included such figures as D. H. Lawrence, Georgia O'Keeffe, Paul Strand, Ella Young and Aaron Copland.

Later that year he travelled to Mexico where he studied at the Mexico City University of the Arts and worked as a high school teacher. His US visa having expired, he slipped across the Rio Grande and returned to Taos where he worked as a teacher again until 1932 where he travelled to New York, where he met Helen Hooker, a wealthy young sculptor and tennis player, whom he would later marry.

In 1934, O'Malley was granted a pension by the Fianna Fáil government as a combatant in the Irish War of Independence. Now possessed of a steady income, he married Helen Hooker in London on 27 September 1935 and returned to Ireland. The O'Malleys had three children and divided their time between Dublin and Burrishoole, County Mayo. Hooker and O'Malley devoted themselves to the arts, she was involved in sculpture and theatre, while he made his living as a writer. In 1936, On Another Man's Wound was published to critical and commercial acclaim. O'Malley remained in neutral Ireland during The Emergency, involving himself as a member of the Local Security Force. However, during the war years the O'Malleys' marriage began to fail.[15]

Helen O'Malley began to spend more and more time with her family in the United States and, in 1950, took two of the couple's three children to live with her in Colorado. She divorced her husband in 1952.[15]

The third child stayed with his father. O'Malley sent his son to a boarding school in England, as, despite his republican politics, O'Malley was an admirer of the English public school system of education.

Throughout his life O'Malley endured considerable ill-health from the wounds and hardship he had suffered during his revolutionary days. He was given a state funeral after his death in 1957. A sculpture of Manannán mac Lir, donated by O'Malley's family, stands in the Mall in Castlebar, County Mayo.

Writings

O'Malley's most celebrated writings are On Another Man's Wound, a memoir of the War of Independence, and The Singing Flame, an account of his involvement in the Civil War. Raids and Rallies includes an account of the period he was required by the IRA Command under Lynch to hide in secret at Sheila Humphreys' house near Ballsbridge. The house was raided on 4 November 1922 during which the Ryan sisters were arrested with O'Malley. They were consigned to internment in Mountjoy Prison. He spent nearly three years inside before being released due to pressure from De Valera. The two volumes were written during O'Malley's time in New York, New Mexico and Mexico City between 1929 and 1932.[16]

On Another Man's Wound was published in London in 1936, although the seven pages detailing O'Malley's ill-treatment while under arrest in Dublin Castle were omitted. An unabridged version was published in America a year later under the title Army Without Banners: Adventures of an Irish Volunteer. The New York Times described it as "a stirring and beautiful account of a deeply felt experience" while The New York Herald Tribune called it "a tale of heroic adventure told without rancor or rhetoric."[16]

In 1928 O'Malley defined his attitude in a letter to fellow-Republican Sheila Humphreys:

I have the bad and disagreeable habit of writing the truth as I see it, and not as other people (including yourself) realise it, in which we are a race of spiritualised idealists with a world idea of freedom, having nothing to learn for we have made no mistakes.[17]

In an article in The Irish Times in 1996, the writer John McGahern described On Another Man's Wound as "the one classic work to have emerged directly from the violence that led to independence", adding that it "deserves a permanent and honoured place in our literature."[17]

Perhaps reflecting its more controversial theme in Ireland, The Singing Flame was not published until 1978, well after O'Malley's death.[16] He also wrote another book on the revolutionary period, Raids and Rallies, describing his and other fighters' experiences. This book was based on a lengthy series of interviews he had conducted in the 1950s with former IRA men and ran as a highly popular serial in The Sunday Press from 1955-56.[16] In addition, O'Malley wrote large volumes of poetry and contributed to a literary and cultural magazine "The Bell", set up by his fellow republican Peadar O'Donnell.

O'Malley's extensive notes, compiled while he was an active IRA officer, are one of the best primary historical sources for the revolutionary period in Ireland, 1919–23, from the republican perspective. In the 1930s and 1940s he also toured Ireland interviewing veterans of the republican struggle. His papers are now housed in the University College Dublin archives,[18] to whom they were donated by O'Malley's son, Cormac, in 1974. Cormac O'Malley retains the bulk of the remainder of his father's personal papers, poetry, and some manuscripts in his New York residence.

Ernie O'Malley's official military papers on the revolutionary and Civil Wars were published in 2008, under the title, No Surrenders Here!. His autobiographical works are the main inspiration behind the Ken Loach film The Wind That Shakes the Barley, and the character of Damien is based partly on O'Malley.[19]

See also

- Tom Barry

- Dan Breen

References

- O'Farrell, pages 10 and 106

- Birth Record, Superintendent Registrar District of Castlebar 1897, Group Registration ID - 9965997

- "Census of Ireland, 1911". nationalarchives.ie. 2 April 1911. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- Ernie O'Malley, On another man's wound, p.10

- English, Richard (1999). Amazon.com: Ernie O'Malley: IRA Intellectual (9780198208075): Richard English: Books. ISBN 0198208073.

- Lysaght, Charles (16 July 2006). "The excellent honour of ambassador suits you, sir". Irish Independent.

- "National Archives: Census of Ireland 1911". census.nationalarchives.ie. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- E O'Malley, On another man's wound, p.61.

- O'Malley, On another man's wound, p. 95.

- Cottrell, Peter (2006). The Anglo-Irish War: The Troubles of 1913–1922. Essential Histories. 65. Osprey Publishing. p. 47. ISBN 978-1-84603-023-9. Retrieved 19 December 2014.

- O'Connor, Emmet (March 2003). "Communists, Russia, and the IRA, 1920-1923". The Historical Journal. 46 (1): 115–131. doi:10.1017/S0018246X02002868. JSTOR 3133597.

- "Anno O'Rahilly, Genealogy research by Mark Humphrys, 1983-2017". Humphrysfamilytree.com. Retrieved 25 May 2017.

- "Ernie O'Malley". Oireachtas Members Database. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Ernie O'Malley". ElectionsIreland.org. Retrieved 20 May 2012.

- "Ernie O'Malley profile". irishartsreview.com. Archived from the original on 9 May 2004. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- O'Malley, Cormac K. H. (5 December 2003). "Project MUSE - The Publication History of On Another Man's Wound". New Hibernia Review. muse.jhu.edu. 7 (3): 136–139. doi:10.1353/nhr.2003.0067.

- English, R. (1999). Ernie O'Malley: IRA Intellectual. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198208075. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- "Papers of Ernie O'Malley (1897–1957)". Archived from the original on 25 August 2006. Retrieved 2 August 2006.

- Smith, Damon (18 March 2007). "The agitator". The Boston Globe.

Bibliography

Writings

- O'Malley, Ernie (1936). On Another Man's Wound.

- O'Malley, Ernie. The Singing Flame. (revised and expanded 2002)

- O'Malley, Ernie (1985). Raids and Rallies.

- O'Malley, Ernie (2004). Cormac K.H. O'Malley & Anne Dolan (ed.). No Surrender Here!: The Civil War Papers of Ernie O'Malley 1922–1924.

Secondary sources

- Cosgrove, Mary (Fall–Winter 2005). Ernie O'Malley: Art and Modernism in Ireland. Éire-Ireland. pp. 85–103.

- Richard English (1998). Ernie O'Malley, IRA Intellectual.

- O'Farrell, Padraic (1983). The Ernie O'Malley Story.

Further reading

- O’Malley, Cormac and Barron, Juliet Christy, (2015) Western Ways: Remembering Mayo Through the Eyes of Helen Hooker and Ernie O’Malley, Mercier Press.

External links

- A website dedicated to sharing information O'Malley's life and times

- "The inborn hate of things English": Ernie O'Malley and the Irish Revolution 1916–1923

- An account of O'Malley's association with Achill Island

- Ernie O'Malley Papers at Tamiment Library and Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives at New York University