Unionism in Ireland

Unionism in Ireland is a political tradition on the island that professes loyalty to the Crown and Constitution of the United Kingdom. The overwhelming sentiment of a once ascendant minority Protestant population, in the decades following Catholic Emancipation (1829) it mobilised to oppose the restoration of an Irish parliament. As "Ulster unionism," in the century since Partition (1921), its commitment has been to the retention within the United Kingdom of the six Ulster counties of Northern Ireland. Within the framework of a peace settlement for Northern Ireland, since 1998 unionists have reconciled to sharing office with Irish nationalists in a devolved administration, while continuing to rely on the connection with Great Britain to secure their cultural and economic interests.

Irish Unionism 1800-1904

The Act of Union 1800

.jpg)

In the last decades of the Kingdom of Ireland (1542-1800) Protestants in public life advanced themselves as "Irish patriots." The focus of their patriotism was an Ascendancy parliament in Dublin. Largely confined on a narrow franchise to members of the Anglican communion, the established Church of Ireland, the parliament denied equal protection and public office to Protestant "Dissenters" and to the Kingdom's dispossessed Roman Catholic majority. The high point of this parliamentary patriotism was the formation during the American War of Independence, of the Irish Volunteers and, as that militia drilled and paraded, the securing in 1782 of the parliament's legislative independence from British Privy Council in London.

In Presbyterian Ulster, where confident in their own numbers Protestants looked upon the Catholic interest with relative equanimity, combinations of tradesmen, merchants, and tenant farmers protested against a parliament that continued in the service of the Kingdom's greatest proprietors and of an executive in Dublin Castle still appointed, through the office of the Lord Lieutenant, by English ministers. Despairing of reform and emboldened by the prospect of aid from revolutionary France, these United Irishmen resolved that "if the men of property will not support us, they must fall,"[1] and that if they were to fall that "Protestant, Catholic and Dissenter" should unite "to break the connection with England."[2] Such Jacobin resolve was broken upon the wheel of their 1798 uprising, and by the reporting of rebel outrages against Protestant Loyalists in the South (the Scullabogue and Wexford Bridge massacres).[3]

The British government, that had had to deploy its own forces to suppress the rebellion and to turn back and defeat French intervention, resolved upon a Union. For the chief of Castle executive Lord Castlereagh, the principal merit of a bringing Ireland directly under the Crown in the Westminster Parliament was a resolution of what was ultimately the key issue for the governance of the country, the Catholic question.:[4]

Linked with England, the Protestants, feeling less exposed, would be more confident and liberal; and the Catholics would have less inducement to look beyond that indulgence which is consistent with the security of our establishment.[5]

However, opposition from within this "establishment," and not least from the King, George III, obliged Castlereagh to defy what he saw as "the very logic of the Union."[6] The Union bill that, with a generous distribution of titles and emoluments, he put through the Irish Parliament omitted the provision for Catholic emancipation. A separate Irish executive in Dublin was retained, but representation, still wholly Protestant, was transferred to Westminster constituted as the Parliament of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland.

In decades that followed the Act of Union (1800) Protestants of every sectarian persuasion and class reconciled to the loss of an Irish parliament which, having refused every call for reform--to remove the last of the sacramental tests, to curb patronage, to broaden the franchise--"they had in any case little cause to lament."[7] In time the legislative union with Great Britain came to be seen both as occasion for their relative prosperity and, as the Roman Catholic majority in Ireland began to stir and gather in a new national movement, as a guarantee of their "liberty."

Catholic Emancipation and the emergence of Nationalist Ireland

It took the Union thirty years to deliver on the promise of Catholic Emancipation (1829)—to admit Catholics to Parliament—and permit an erosion of the Protestant monopoly on position and influence. An opportunity, had the Union been earlier "complete," to integrate Catholics through their re-emerging propertied and professional classes as a "dilute minority" may have passed. As it was, on the morrow of Emancipation it was clear they had chosen "another route."[8] In 1830, their champion, leader of the Catholic Association, Daniel O’Connell, invited Protestants to join in a campaign to "repeal" the Union and restore the Kingdom of Ireland under the Constitution of 1782.

Contending under that constitution with a parliament narrow and corrupt but whose historic jurisdiction they implicitly accepted, Dissenters had been content to invoke general democratic principle, those universal "Rights of Man and of the Citizen" proclaimed in 1789 by the French Constituent Assembly and defended by Thomas Paine. Emancipated within the jurisdiction of the Westminster parliament, Catholics had to preface principle with the vindication of an historical right—of the Irish as "a people" deserving of a separate representation. Ireland was re-imagined as a political nation through popular history, balladry, and literature which chronicled the centuries-long resistance of "the Gael" and, when all else was lost, of the "dark days" of endurance under the Penal Laws.[9] Scarcely avoided was the suggestion that in this "story of the nation" Irish Protestants were, as John Banim (the "Walter Scott of Ireland") proposed, "half-countrymen."[10]

One response to this imputation of "foreignness" to Protestants was inscribed defiantly upon the Williamite banners of the marching Orange Order: "Derry, Aughrim, and the Boyne," "Sons of Conquerors." But short of embracing what Catholics viewed as Ascendancy "triumphalism," the difficulty for Protestants in orientating themselves to the nationalist movement was acute. It was made more so by the reality that in the greater part of country the only element around which the movement could reliably build was the Catholic clergy.[11]

Protestant unity and the New Reformation

In an incident celebrated by unionists, in 1841, disdaining to engage a "bully . . . the Cock of the North," O’Connell refused the challenge of the then Moderator of the Presbyterian General Assembly, Henry Cooke, to debate Repeal in Belfast.

Look at the town of Belfast. When I was myself a youth I remember it almost as a village. But what a glorious sight does it now present—the masted grove within our harbour—our mighty warehouses teeming with the wealth of every climate - our giant manufactories lifting themselves on every side...And all this we owe to the Union... Mr. O'Connell look at Belfast, and be a Repealer--if you can.[12]

A critic of the "lax" ("Arian") theology he believed had indulged the republicanism of the 1790s, Cooke had emerged as an early evangelist for a New or Second Reformation. This was a revivalist movement that owed much to Ulster-Presbyterian ministries in the United States (from where Cooke received his doctorate). In Ireland the new evangelism lent itself to a politically-charged prosperity gospel. In The Mystery Solved: or, Ireland's Miseries; the Grand Cause and Cure, a work that caused a "sensation" on its publication in 1852 (a copy was sent to every member of Parliament, and one was "graciously accepted" by Queen Victoria), Dr. Edward Marcus Dill, a "General missionary agent" of the Presbyterian Assembly, argued that the poverty of Catholic Ireland was rooted, not in a history of political disability, but in a counterfeit faith.[13]

Venture the supposition that Romanism is false and Protestantism is true, and like some dissected map the most shapeless part of Ireland's puzzle falls into its place in a moment. Observe how its unfolds every mystery in our physical and moral state: and explains why the 'Black North' is a garden, and the 'Sunny South' a wilderness; why southern jails are crowded and northern ones half empty . . . Mark how its solves our political enigmas; shows why Ulster flourishes and Munster declines beneath the same law[14]

Accused of seeking proselytising advantage in hunger and distress, Dill's "home mission" of preaching the gospel to the Irish peasantry was the subject of bitter Catholic commentary.[15] The Catholic Church itself responded with its own "devotional revolution" and an "Hiberno-Roman" mission that, under the direction of Cardinal Archbishop Paul Cullen, was ultimately extended through Britain to the entire English-speaking world.[16]

Victim of this polarisation of Protestant-Catholic relations were the proposals of the Dublin Castle executive to provide Ireland, "in advance of anything available at that time in England", a system of grant-aided non-denominational education.[17] In 1830, when the proposal was for primary schools, Cooke, at once scented danger to the Protestant interest. He persuaded the Presbyterian Synod to independently organise schools in which there could be no "mutilating of scripture."[18] The Catholic hierarchy reciprocated in 1845, objecting to a similar scheme for tertiary education, the Queen's Colleges, as "dangerous to the faith and morals of the people."[19] Disregarding the plea of Young Irelander Thomas Davis that "the reasons for separate [Catholic/Protestant] education are reasons for separate life", O'Connell joined the more recalcitrant of the bishops in condemning the "Godless colleges".[20]

To the Presbyterian home mission Cooke lent his enthusiasm for preaching in the Irish language, but he saw in the new evangelism occasion to advance a more immediate purpose, "Protestant unity." It had been a newly installed Church of Ireland Archbishop of Dublin, William Magee, who in 1822 had first declared the absolute necessity for a "Second Reformation," and Methodists had been at the forefront of the subsequent "Bible War."[21] The central revivalist commitment to personal witness through Jesus Christ did appear to transcend the ecclesiastical differences between Protestants[22] at a time, so Cooke insisted, of supreme political peril.[23]

In 1834, at a mass demonstration hosted upon his estate by the 3rd Marquess of Downshire, a disillusioned "Emancipationist", Cooke proposed a "Christian marriage" between the two main Protestant denominations. It would be a union of "forbearance where they may differ" but of "cooperation in all matters [of] common safety."[24]

Most Presbyterians, at the time, were not as "forebearing" as Cooke would have wished. They continued to baulk at the Ascendancy's high Tory politics and patronage of the Orange Order. With other Nonconformists, at election Presbyterians tended to favour Whigs (notwithstanding their dalliance with O'Connell) or, as they later emerged tenant-rights Liberals.[25] But Cooke's "marriage banns" were a portent of the future. Their call for a pan-Protestant alliance resonated from the moment it was clear that nationalists, where they had failed to persuade in Ulster, were beginning to succeed in England.

The Irish party challenge at Westminster

In December 1885, the Liberal Party leader William Ewart Gladstone announced his conversion to a compromise that had been prepared by O’Connell prior to his death in 1847. Ireland would have a measure of "home rule" within the United Kingdom.

Up to, and through, the great starvation, the Irish Famine, of the 1840s, successive governments, Whig and Tory, had maintained a studied indifference to the systemic consequences in Ireland of peasant dispossession and unchecked landlordism. The issues of a low-level agrarian war came to Westminster in 1852. In a direct challenge to the landed-interest Irish Conservative Party, what the Young Irelander Gavan Duffy optimistically described as the "League of North and South" returned 50 tenant-rights MPs. For unionism the more momentous challenge lay in the wake of the 1867 Reform Act. In Great Britain it produced an electorate that no longer identified instinctively with the landed interest. In Ireland, where it more than doubled in size, in 1874 the electorate returned 59 Members for the Home Rule League who were to sit as the Irish Parliamentary Party (IPP). Of these, only two were returned from Ulster (from the border county of Cavan): "Ulster protestants, as a body, were as strongly opposed to home rule as they had been to repeal."[26]

The Home Rule League was led nonetheless by the son of a Church of Ireland rector and an Ulsterman. Isaac Butt had been seduced from his commitments to the Conservative Party and Orange Order by the failure of the Union to give famine-stricken Cork the relief that he believed would have been given Cornwall.[27] In the British House of Commons Butt was seconded by another maverick from the north, a Catholic convert, Joseph Biggar. Biggar led an aggressive form of obstructionism that deliberately courted the judgement that as a body the IPP was "practically foreign" and "valued its place in the House only as a means of making itself so-disagreeable as to obtain its release."[28]

Gladstone in his first ministry (1868-1874) attempted conciliation. In 1869 the Church of Ireland was disestablished and in 1870 a Land Act acknowledged for the first time a political responsibility for agrarian conditions. But spurred by the collapse of agricultural prices in the Long Depression, the Land War intensified. From 1879 it was organised by the direct-action Irish National Land League, led by another of Butt's lieutenants (and who, like Butt, bestowed upon the Nationalist movement "a deceptively ecumenical air") the southern Protestant Charles Stewart Parnell.[29] As late as 1881 Gladstone resorted (over a 41-hour filibuster by IPP) to a Coercion Act allowing for arbitrary arrest and detention in protection of "person and property."

The final and decisive shift in favour of constitutional concessions came in the wake of the Third Reform Act of 1884. The near-universal admission to the suffrage of male heads of household tripled the electorate in Ireland. The 1885 election returned an IPP of 85 Members (including 17 from Catholic-majority areas of Ulster), marshalled now under the leadership of Parnell. Gladstone, whose Liberals lost all 15 of their Irish seats, was able to form his second ministry only with their Commons support.

Reaction to Gladstone’s Home Rule Bills

The Government of Ireland Bill that Gladstone tabled in June 1886 incorporated what he imagined were assurances for Unionism. The 200 or so popularly elected members of the "Irish Legislative Body" would sit in session with 28 Irish Peers and a further 75 Members elected on a highly restrictive property franchise. The anticipated result might have been rough nationalist-unionist parity.

What was clear to unionists was that Ireland was being put out of the United Kingdom. The "Imperial Parliament" in London would retain sovereignty ("devolving" powers to Dublin) but no Irish representation. What was proposed was a proximate restoration of the constitution of the Kingdom of Ireland as it had existed before 1782: a colonial legislature in Dublin with an executive accountable to London through the Lord Lieutenant. But it was with arrangements for representation in Ireland on terms, and in an era, that unionists feared could only march in one direction, toward majority rule and total separation. "No Irishman worthy of the name", declared the anti-home-rule Liberal James Shaw, "would be contented" with the "subordination and dependence" implicit in the new dispensation. The only "reasonable hope of peace" lay in either "complete union or complete separation".[30]

The alarm among Protestants appeared to surmount all previous distinctions of party or class and, in addition to express fears of "Rome Rule," spoke to their growing material concerns. These were not only those of the existential struggles in the countryside over land and rent. The upper and middle classes found in Britain and the Empire "a wide range of profitable careers--in the army, in the public services, in commerce--from which they might be shut out if the link between Ireland and Great Britain were weakened or severed."[31] That same link was critical for all those engaged in the great export industries of the North—textiles, engineering, shipbuilding—for whom the Irish hinterland was less present than Clydeside or the North of England.

For Protestant workers there was the concern that Home Rule would force accommodation of the growing numbers of Catholics arriving at mill and factory gates from the outlying country and western districts. While the plentiful supply of cheap labour helped attract the English and Scottish capital that employed them, Protestant workers organised to protect "their" jobs (a function performed in the skilled trades by the apprenticeship system) and tied housing. The once largely rural Orange Order was given a renewed lease and mandate.[32] The pattern, in itself, was not unique to Belfast or its satellites. Glasgow, Manchester, Liverpool and other British centres experiencing heavy Irish immigration developed similar nativist, and even Orange, ward and workplace politics,[33] to which Irish Unionists made conscious appeal.[34]

Gladstone's own party was split on Home Rule and the House divided against the measure. People were already battling on the streets when the news reached Belfast. The rumour among unionists was that the rioting, which took upwards of fifty lives, had been triggered when a group of Catholic navvies, anticipating the Bill's passage, pushed a Protestant out of their dock, warning him that "neither he nor any of his sort should get leave to work there, or earn a loaf there or any other place."[35]

In 1891 Ulster's Liberal Unionists, part of larger Liberal break with Gladstone, entered the Irish Unionist Alliance and at Westminster took the Conservative whip. In an epitaph for the Liberal Party in Ireland, Shaw attributed Gladstone's swing from coercion to Home Rule to "half-hearted, wavering, inconsequent policy. . . , continued through centuries of confusion and misrule, which would neither thoroughly subdue the Irish as enemies, nor frankly accept them as friends and fellow subjects."[36]

In 1892, despite bitter division, in which the Catholic hierarchy took a heavy hand, over the personally-compromised leadership of Parnell, the Nationalists were able to help Gladstone to a third ministry. The result was a second Home Rule bill. It was greeted by an Ulster opposition more highly developed and better organised.

A great Ulster Unionist Convention was held in Belfast organised by the Liberal Unionist Thomas Sinclair, in earlier years "an articulate critic of the Orange Ascendancy."[37] Speakers and observers dwelt on the diversity of creed, class and party represented among the 12,300 delegates attending. As reported by the Northern Whig there were "the old tenant-righters of the 'sixties' . . . the sturdy reformers of Antrim. . . the Unitarians of Down, always progressive in their politics . . . the old-fashioned Tories of the Counties . . . modern Conservatives . . . Orangemen . . . All these various elements--Whig, Liberal, Radical, Presbyterian, Episcopalian, Unitarian and Methodist . . united as one man."[38]

While references to Catholics were conciliatory the Convention resolved:

to retain unchanged our present position as an integral portion of the United Kingdom, and protest in the most unequivocal manner against the passage of any measure that would rob us of our inheritance in the Imperial Parliament, under the protection of which our capital has been invested and our home and rights safeguarded; that we record out determination to have nothing to do with a Parliament certain to be controlled by men responsible for the crime and outrage of the Land League . . . many of whom have shown themselves the ready instrument of clerical domination.[39]

After mammoth parliamentary sessions the bill, which did allow for Irish MPs, was passed by a narrow majority in the Commons but went down to defeat in the overwhelmingly Conservative House of Lords. The Conservatives formed a new ministry.

Constructive Unionism

.svg.png)

The new Prime Minister Lord Salisbury, who had expressed the view that "free representative institutions" are best confined to "people who are of Teutonic race," believed his government should "leave Home Rule sleeping the sleep of the unjust."[40] Irish Conservatives applauded when in 1887 Dublin Castle was given standing power to suspend habeas corpus. However, as Chief Secretary for Ireland, his nephew Gerald Balfour, determined upon a "constructive" course, pursuing reforms intended, as some saw it, to "kill home rule with kindness."

For the express purpose of relieving poverty and reducing emigration, in the "congested districts" of the west Balfour initiated a programme not only of public works, but of subsidy for local craft industries. A new Department of Agriculture and Technical instruction broke with the traditions of Irish Boards by announcing that its aim was to "be in touch with public opinion of the classes whom its work concerns, and to rely largely for its success upon their active assistance and co-operation."[41] It supported and encouraged dairy cooperatives, the "creameries" that were to be an important institution in the emergence of a new class of independent smallholders.[42]

Greater reform followed when, with the support of the splinter Liberal Unionist Party, Salisbury returned to office in 1895. The Land Act of 1896 introduced for the first time the principle of compulsory sale to tenants, through its application was limited to bankrupt estates. "You would suppose," said Sir Edward Carson, Dublin barrister and the leading spokesman for Irish Conservatives, "that the Government were revolutionists verging on Socialism.".[43] Having been first obliged to surrender their hold on local government (transferred at a stroke in 1898 to democratically-elected councils), the old landlord class had the terms of their retirement fixed by the Wyndham Land Act of 1903. They had ceased to be an effective social or political influence.

"The Ulster Option" 1905-1920

"The democracy of Ulster"

.jpg)

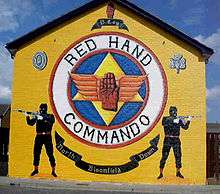

In 1905 the Ulster Unionist Council was established to coalesce unionists in the north including, with 50 of 200 seats, the Orange Order. Until then, unionism had largely placed itself behind those of Anglo-Irish landed interest valued for their high-level connections in England. The UUC still accorded a degree of precedence to aristocracy. Castlereagh's descendant and former Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, the Marquess of Londonderry presided over its Executive (and Lady Londonderry over the Ulster Women's Unionist Council). The Council also retained the services of Carson, from 1892 MP for Trinity College, Dublin. But marshalled by Captain James Craig, a millionaire director of Belfast's Dunville Whiskey, it was northern employers who were undertaking the real political and organisational work.

The manufacturers and merchants of Belfast and neighbouring industrial districts were, for the most part, of farming and Presbyterian stock and had little natural sympathy for the old landed interest.[44] Crucially, while southern landowners had been politically at war with their tenants, northern employers could generally count on voting with the majority of their own workforce. For Nationalists this was a matter employers playing "the Orange card." Employers did look to sectarian division to weaken labour protest, but sash-wearing loyalists were not necessarily reliable. In the mind of many ordinary Belfast Protestants there was no contradiction between the defence of Protestant principle and political radicalism, "indeed, these were often seen as one and the same because it was the wealthy who were most prone to conciliation and treachery".[45]

In 1902 the shipyard worker Thomas Sloan, presented as the democratic candidate by the plebeian Belfast Protestant Association, defeated the Conservative Party nominee for South Belfast. His campaign was marked by what his opponents considered a classic piece of bigotry. Sloan protested the exemption of Catholic convents from inspection by the Hygiene Commission (the Catholic Church should not be "a state within a state"). But it was also as a trade unionist that Sloan criticised the "fur-coat brigade" in the leadership of unionism. With his Independent Orange Order Sloan supported dock and linen-mill workers, led by the syndicalist James Larkin, in great Belfast Lockout of 1907.[46][47] ("Russellite Unionists" were another expression of class-related tension. Thomas Russell MP, the son of an evicted Scottish crofter, broke with the Conservatives in the Irish Unionist Alliance to be returned to Westminster from South Tyrone in 1906 as the champion of the Ulster Farmers and Labourers Union).[48][49]

Loyalist workers were conscious, and resentful, of the imputation that they were the retainers of "big-house unionists." A manifesto signed in the spring of 1914 by two thousand labour men, on behalf of the only "fully organised and articulate" trade unionists in Ireland, repudiated the suggestion of the "Radical and Socialist press" that Ulster was being manipulated by "an aristocratic plot." If Sir Edward Carson led in the battle for the Union it was "because we, the workers, the people, the democracy of Ulster, have chosen".[50] Chairman of the Boilermakers’ Society, J. Hanna, insisted that it was as the "freemen and as members of the greatest democracy in Great Britain and Ireland, the organised trade unions of the country," that "they would not have Home Rule."[51]

The difficulty for nationalists and for those, like James Connolly, who believed that class solidarity should draw workers down the path of Irish independence, was that without having to break unionist ranks with their employers, workers were beginning to see the link to what the Belfast labour leader William Walker represented to Connolly as a "larger and more advanced democracy" paying dividends.[52] Thanks to the legislative union with Great Britain, workers in Ireland were able to benefit from the majorities found "across the water" for labour and social reform-—under the a Liberal-majority government from 1906, for the Trade Disputes Act 1906, for the National Insurance Act 1911 and for the People's Budget 1911.

The nationalist cause in the industrial North was not helped by those who suggested that collective bargaining, social security and progressive taxation were principles for which majorities would not be as readily found in a Dublin Parliament. Objecting to an "inefficient and extravagant government . . . which had no parallel in Europe," Sinn Fein President Arthur Griffith proposed that "imperialism and socialism—forms of the cosmopolitan heresy and in essence one—have offered man the material world. Nationalism has offered him a free soul".[53] For Ulster workers, as for Ulster employers, there was interest and calculation in a common Unionism.

In an open letter to U.S. President Woodrow Wilson, in 1918 Edward Carson wrote:[54]

The Ulstermen of to-day, forming as they do the chief industrial community in Ireland, are as devoted adherents to the cause of democratic freedom as were their forefathers in the eighteenth century. But the experience of a century of social and economic progress under the legislative Union with Great Britain has convinced them that under no other system of government could more complete liberty be enjoyed by the Irish people.

Unionism and women's suffrage

At what was to be the high point of mobilisation in Ulster against Home Rule, the "Covenant Campaign" of September 1912, the Unionist leadership decided that men alone could not attest to the determination of the Unionist people to defend "their equal citizenship in the United Kingdom." Women were asked, not to sign the Covenant, whose commitment to "all means which may be found necessary" implied a readiness to bear arms, but to "associate" themselves "with the men of Ulster" through their own Declaration. A total of 234,046 women signed the Ulster Women's Declaration; 237,368 men signed the Solemn League and Covenant.[55]

Unionist women had been involved in political campaigning from the time of the first Home Rule Bill in 1886. Some were active suffragettes. Isabella Tod, an anti-Home Rule Liberal and campaigner for girls education, was an early pioneer. Determined lobbying by her North of Ireland Women's Suffrage Society ensured the 1887 Act creating a new municipal franchise for Belfast (a city in which, thanks to their employment in linen and tobacco mills, women predominated) conferred the vote on "persons" rather than men. This was eleven years before women elsewhere Ireland gained the vote in local government elections.[56] During the height of the Home Rule crisis in 1912-1913 the WSS held at least 47 open-air meetings in Belfast, and mounted dinner-hour pickets at factory gates to engage working women.[57]

Unionist WSS activists were not impressed by the women's Ulster Declaration. Elizabeth McCracken, a regular contributor to the Belfast News Letter, noted the failure Unionist women to formulate "any demand on their own behalf or that of their own sex."[58] The Declaration, nonetheless, was a political affirmation of intent by women, organised and publicly staged by women. Founded in January 1911, with well over 100,000 members the Ulster Women's Unionist Council UWUC was the largest women's political group in Ireland.[59]

Determined to "sink all differences in favour of the Union," the UWUC avoided public comment on the suffrage question. But for many women signing the Council's Declaration was a first taste of political involvement. In September 1913 it appeared that the Unionist Council had determined it should not be their last. The Council informed the UWUC that "the draft articles" for a Provisional Government to be set up in the event of Home Rule being legislated "include the franchise for women."[60] The Irish Parliamentary Party made no such commitment for a Dublin parliament. In contrast to the Ulster Unionists who divided, in 1912 the Nationalists had voted as a bloc against a "Conciliation" Bill that would have conceded the principle of women's parliamentary suffrage, albeit on a highly restrictive property basis.[61]

In the spring in 1914, seeming to over rule Craig whom WSS noted had "always supported suffragist measures in parliament," Carson made it clear he could not commit his party on so contentious an issue as votes for women.[62] Dorothy Evans of the militant Women's Social and Political Union declared that as Carson had proved himself "no friend of women" the WSPU was ending "the truce we have held in Ulster." In the months that followed, together with Elizabeth Bell, the first woman in Ireland to qualify as a doctor and gynaecologist, McCracken was implicated in a series of arson attacks on Unionist-owned buildings and on male recreational and sports facilities.[63] In July 1914, in a plan hatched with Evans, Lillian Metge bombed Lisburn Cathedral.[64]

In August 1914, following the lead of Emmeline and Christabel Pankhurst in Britain, unionist suffragists suspended their agitation for the duration of the European war.

1912 Home Rule Crisis

In 1911 a Liberal administration was once again dependent on Irish nationalist MPs. In 1912 the Prime Minister, Herbert Asquith, introduced the Third Home Rule Bill. A more generous dispensation than the earlier bills, it would, for the first time, have given an Irish parliament an accountable executive. It was carried in the Commons by a majority of ten. As expected, it was defeated in the Lords, but as result of the crisis engendered by the opposition of the peers to the 1909 People's Budget the Lords now only had the power of delay. Home Rule would become law in 1914.

There had long been discussion of giving "an option to Ulster." As early as 1843, The Northern Whig reasoned that if differences in "race" and "interests" argue for Ireland's separation from Great Britain then "the Northern 'aliens', holders of 'foreign heresies' (as O'Connell says they are)" could not be denied their own "distinct kingdom", Belfast as its capital.[65] In response to the First Home rule Bill in 1886, "Radical Unionists" (Liberals who proposed federalising the relationship between all countries of the United Kingdom) likewise argued that "the Protestant part of Ulster should receive special treatment . . . on grounds identical with those that support the general contention for Home Rule"[66] Northern unionists expressed no interest in a Belfast legislature. As The Northern Whig had noted, the only desire was "to continue as fellow-subjects of all the inhabitants of the British Isles." But the riposte to nationalists remained. In summarising The Case Against Home Rule (1912), L. S. Amery observed that against "every argument that can justify three million Nationalists asserting their national idea over a million Unionists" is "the stubborn fact that if Irish Nationalism constitutes a nation, then Ulster is a nation too."[67]

Faced with the eventual enactment of Home Rule, Carson appeared to press the point. On 28 September 1912, ‘Ulster Day’ he was the first to sign, in Belfast City Hall, Ulster's Solemn League and Covenant.[68] This bound signatories "to stand by one another in defending for ourselves and our children our position of equal citizenship in the United Kingdom, and in using all means which may be found necessary to defeat the present conspiracy to set up a Home Rule Parliament in Ireland." (The historic reference, widely understood, was to the sixteenth-century Scottish Covenants that had bound Presbyterians to defend in arms their reformed faith)

In January 1913, Carson declared for the exclusion of Ulster and called for the enlistment of up to 100,000 Covenanters as drilled and armed Ulster Volunteers. On 23 September, the second Ulster Day, he accepted Chairmanship of a Provisional Government, elaborately organised by Craig. If Home Rule were imposed "we will be governed as a conquered community and nothing else."[69]

For Carson and for other southern Unionists the object of the gamble on Ulster, with the surety of support from British Conservatives and possibly, following the incident at Curragh, in the Army, was to out manoeuvre both the Government and the Nationalists, so as to retain Ireland as a whole under the direct authority of the Crown in Westminster. Ulster excluding itself from the jurisdiction of a Dublin Parliament was the threat, but if "an option" for Ulster was all that was achieved, it would have been, as Carson later accounted it, a loss.[70]

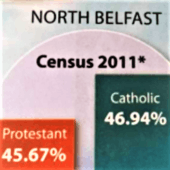

For Unionists in the North, the integrity of Ireland within the United Kingdom was not an existential issue. With the signing of the Covenant and the creation of the Provisional government, northern Protestants had effectively "proclaimed themselves a people apart from the rest of Ireland, and decreed the exclusion of Unionists, as well as Nationalists, who had the misfortune to reside on the wrong bank of the Boyne." The differences in class between the two sections of Unionism were complicated by the unresolved differences of creed. One of the arguments that was now employed behind the scenes for the exclusion of a smaller enclave of six, rather than the full nine, Ulster counties is that it would possess not merely a Protestant but a Presbyterian majority.[71]

Economic differences also made for separation. Agricultural Ulster, and Belfast as a distribution centre, might have important links with the south and west of the country. But the major industries, textiles, shipbuilding and engineering brought those they engaged into routine contact, not with Limerick, Cork or even Dublin, but with Glasgow, Liverpool and London. An Irish partition would not involve the potential loss of a valued hinterland, entrepôt or market.

Ultimately, as recalled by the man celebrated for landing German guns for Ulster Volunteers, Major Frederick H. Crawford, the decision on the Ulster Unionist Council was that “we could not dictate to the rest of Ireland.” Beyond the Protestant pale in Ulster there was simply no hope of rescuing Unionist brethren from the strength of the demand for Home Rule and from the British sympathy it engaged.

I moved a resolution that in future our policy be confined to Ulster . . . This very naturally caused dismay among the Unionists of the South and West but when we asked them for an alternative they could suggest no alternative.[72][73]

Partition

With the Nationalists seeking to match the Ulster Volunteers by drilling and arming of National Volunteers, in July 1914 King George V called the parties to a conference of Buckingham Palace. The IPP leader John Redmond insisted that if any part of Ireland was to be excluded from Dublin's jurisdiction it should only be those limited areas in the north-east with clear Unionist majorities. Carson, still seeking the leverage that might induce Nationalists to settle on terms more conducive to the continued sovereignty of the Crown in Westminster, insisted on a “clean cut” for the whole nine counties of Ulster. If this was done generously, he suggested that Ulster might, in time, “come in.” For a few days the conference, in words of Winston Churchill, “toiled round the muddy byways of Fermanagh and Tyrone” and no amending bill was agreed.[74]

On August 4, 1914, the United Kingdom declared war on Germany. A few weeks later the Home Rule bill received Royal Assent but with implementation suspended for the duration of European hostilities. With the issue of exclusion unresolved, leaders on both sides entered into a rival solicitation of Government favour by committing themselves, and their volunteers, to the war effort. Having, on the eve of war, been under growing pressure to set up his Provisional Government, Carson declared that “England difficulty is not Ulster’s opportunity . . . We do not seeks to purchase terms by selling our patriotism.”[75]

That, however, was how Redmond's position came to be perceived on the nationalist side. Seizing upon “England difficulty,” contingents of republican Irish Volunteers and Connolly's Citizen Army, ensured that while Irishmen, at Redmond's urging, were sacrificing themselves for the sake of “Catholic Belgium,” Britain could be seen on the streets of Dublin in Easter 1916 suppressing an Irish “strike for freedom.” In the aftermath of the Rising and in the course of a national campaign against military conscription, the IPP ‘s capital was exhausted.[76][77]

Sensing an opportunity, at the hastily arranged Irish Convention in Dublin in 1917, the Southern unionists' leader Lord Middleton offered the beleaguered IPP the immediate establishment of an all-Ireland parliament that, among other guarantees for unionists, would split fiscal powers with Westminster and surrender any ambition for an independent tariff policy. But the decision of the Lloyd George and his Cabinet to simultaneously introduce conscription to Ireland--in effect, to make the first order of an Irish government cooperation in the impressment of men for the Western Front--ruined the credibility of the proposal with nationalists[78] and spelt the end of Home Rule as a popular cause.[79] Ulster Unionists remained committed to "exclusion."

In February 1918, Carson, pressed by Lloyd George for concessions, returned to the Radical Unionist scheme of the 1880s. He proposed a United Kingdom federation of England, Scotland, Ulster and the South of Ireland. But the plan evoked no nationalist response.[80]

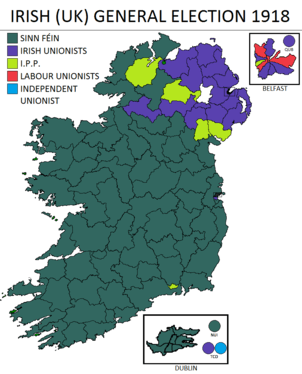

In the "Khaki election" of December 1918, the first Westminster poll since 1910 and the first with all adult males and women from age thirty eligible to vote (the electorate tripled), the IPP was almost wholly replaced in nationalist constituencies by Sinn Féin. Acting on their mandate, Sinn Féin MPs met in Dublin in January 1919 as the Dáil Éireann, the national assembly, of the Republic declared in 1916 and demanded that the "English garrison" evacuate. In the six north-east counties the Unionists took 22 out of 29 seats, with Carson, wary of "Bolshevik" sedition, having taken the additional precaution of running candidates in Belfast as Labour Unionists. (Joining "Red Glasgow" in the demand for a ten hour reduction in the work week, early in 1919 Belfast shipyard and engineering workers sustained the largest and longest walk out in the history of the city).[81]

Violence against Catholics in Belfast, driven out of workplaces and attacked in their districts, and a boycott of Belfast goods, accompanied by looting and destruction, in the South, helped consolidate "real partition, spiritual and voluntary"[82] in advance of the constitutional partition. This otherwise uncompromising Republicans recognised was, at least for now, inevitable. In August 1920 Éamon de Valera, President of Dáil, declared in favour of "giving each county power to vote itself out of the Republic if it so wished."[83]

As they battled with the Republic in the South and West, the British Government, in the hope of brokering a compromise that might yet hold Ireland within the jurisdiction of the "Imperial Parliament," proceeded with the Government of Ireland Act 1920. This provided for two subordinate parliaments. In Belfast a "Northern Ireland" parliament would convene for the six rather than nine Ulster counties (in three, Craig conceded, Sinn Féiners would make government "absolutely impossible for us").[84] The island's remaining twenty-six counties, "Southern Ireland," would be represented in Dublin. In a joint Council, the two parliaments would be free to enter into all-Ireland arrangements.

In 1921, elections for these parliaments were duly held. But in "Southern Ireland" this was for parliament which, by British agreement, would now constitute itself as the Dáil Éireann of the Irish Free State. Under the terms of the Anglo-Irish Treaty, the twenty-six counties were to have the "same constitutional status in the Community of Nations known as the British Empire as the Dominion of Canada."[85] It was not clear to all parties at the time—civil war ensued—but this was de facto independence.

Unionists in Northern Ireland thus found themselves in the unanticipated and unsought position of having to work a constitutional arrangement that was the "by-product of the desperate attempt by British statesmen" to reconcile "the determination of the Protestant population of the North to remain firmly and without qualification within the United Kingdom" with the aspirations of the Nationalist majority in Ireland for Irish unity and independence,[86] a system of government for the six north-eastern counties that was "set up as an instrument of British policy towards Ireland as a whole" and not for their "own good."[87]

Writing to Lloyd George, Craig did insist that its was only as "a supreme sacrifice in the interest of peace" that the North had accepted a home-rule arrangement "not asked for by her representatives."[88] No regret, however, was evident when addressing Belfast shipyard workers. Once Unionists had their own parliament, Craig assured the workers, "no power on earth would ever be able to touch them."[89]

In debating the Government of Ireland Bill, Craig had conceded that, while unionists did "not want" a parliament by which they would be "to a certain extent separated from England", having in the six counties "all the paraphernalia of Government" might help them resist pro-Dublin pressures from a future Liberal and/or Labour government. The argument--the only argument--for a Belfast parliament was "safety".[90]

Unionist majority rule: Northern Ireland 1921-1972

Exclusion from Westminster Politics

Unionists have emphasised that their victory in the Home Rule struggle was "partial." It was not only that twenty-six of thirty-two Irish counties were lost to the Union, but that within the six retained unionists were "unable to make the British government in London fully acknowledge their full and unequivocal membership of the United Kingdom."[91] Even while paying "lip-service" to the proposition, successive British governments failed to act on the principle that Northern Ireland is "an integral part of the United Kingdom."[92]

Although formally constituted by the decision of the six-county Parliament elected in 1920 to opt out of Irish Free State, the Government of Northern Ireland was nonetheless dressed in the trappings of the Canada-style dominion status accorded to the new state in the South. Belfast, like Ottawa, had a two-chamber Parliament, a Cabinet and Prime Minister (Sir James Craig), and the Crown represented by a Governor (the Duke of Abercorn) and advised by a Privy Council. All this was suggestive, not of a devolved administration within the United Kingdom, but of a state constituted under the Crown outside the direct jurisdiction of the Westminster parliament.

The impression that Ireland as a whole was being removed from the orbit of Westminster politics was reinforced by refusal of the parties of Government and Opposition to organise, or canvass for votes, in the six counties.[93] The Conservatives were content that Ulster Unionist Party MPs took their party whip in the House of Commons where, by general agreement, matters within the competence of the Belfast Parliament could not be raised. The Labour Party formed its first (minority) government in 1924 led by a man who in 1905 had been the election agent in North Belfast for the trade-unionist William Walker, Ramsey MacDonald.[94] In 1907 MacDonald's party had held their first party conference in Belfast. Yet, at the height of the Home Rule Crisis in 1913, the British Labour Party had decided not stand against Irish Labour, and in their determination to defer to Irish parties they were to prove unyielding.[95]

There was little incentive for unionists in Northern Ireland to assume the risks of splitting ranks in order to reproduce the dynamic of Westminster politics. Despite its broad legislative powers, the Belfast Parliament did not, in any case, have the kinds of tax and spending powers that might have engendered that kind of party competition. For all its crown-in-parliament pretension and, from 1932, the grandeur of its Buildings at Stormont, the Northern Ireland Parliament was "effectively dependant for supply on the Parliament at Westminster."[96] The principal sources of government revenue, income and corporation taxes, customs and excise, were entirely beyond Belfast's control.[97]

The one unambiguous remit of the Belfast parliament was precisely that in which the Gladstone Home Rule bills had sought to limit a Dublin parliament: internal "law and order." Unionists argue that these were "responsibilities thrust upon them":

[U]nionists leaders had no desire to "dominate" Catholics in the pursuit of loyalist self-determination. As Lord Carson argued in the House of Commons . . ., unionists never asked to govern any Ulster Catholic but were perfectly happy that both Protestants and Catholics should be governed from Westminster. The strongest foundation for the good government of Ulster, he argued, was the fact that Westminster was aloof from the religious and racial distinction of its inhabitants.[98]

Catholics were a third of the population in the six counties: a minority in four, Antrim, Londonderry, Down and Armagh, and a majority in two, Fermanagh and Tyrone. Carson was apprehensive, fearing that with a separate parliament sectarianism could be the only basis for politics. In 1921 he reminded Craig and other Unionist leaders: "We used to say that we could not trust an Irish parliament in Dublin to do justice to the Protestant minority. Let us take care that that reproach can no longer be made against your parliament, and from the outset let them see that the Catholic minority have nothing to fear from a Protestant majority."[99]

On the edge of the Union

In retirement in London Carson confided to the historian Sir Charles Petrie his disillusionment with Belfast politics: "I fought to keep Ulster part of the United Kingdom, but Stormont is turning her into a second-class Dominion."[100] Yet in the first critical years of the new Northern Ireland administration, Carson had stood with other Unionist leaders in urging measures that were both resented by nationalists and poorly understood or appreciated in Great Britain.

One of the first acts of Northern Ireland legislature was to scrap proportional representation (PR), prescribed for all Irish elections 1919. Preference voting was seen as having assisted nationalists to the control of a large number of local and district councils including, in a "blow to Unionist pride", Derry,[101] authorities which then pledged themselves to Dublin. At the annual 12th of July Orange celebrations Carson denounced those who elected swore allegiance to the Republic and vowed that Ulster would "tolerate no Sinn Féin organisation or methods" within its border. At the same time, he declared that "real object" of the independent Labour movement (which had displaced Unionist councillors in Belfast) was "to bring about disunity among our people."[102]

The 1922 Local Government Act that restored the winner-take-all voting system also authorised the N.I. Minister of Home Affairs to rearrange local government constituencies. Unionists dispute that this led to a systematic policy of gerrymander. In what is generally cited as the most egregious example, Derry, from 1923 a "nationalist city" with a Unionist council, they point to the low turnout among a dispirited and abstentionist nationalist electorate, and among Catholics voting to the comparatively strong support for labour candidates.[103] But a generation later, in 1968 when nationalists were taking to the streets of the city, the veteran Unionist MP and former Northern Ireland Attorney General Edmunnd Warnock advised the then Prime Minister Terence O'Neill that "If ever a community had a right to demonstrate against a denial of civil rights, Derry is the finest example." Warnock confessed to his own role in the "manipulation of ward boundaries for the sole purpose of retaining unionist control". Consulting with Craig he had been told that "the fate of our constitution was on a knife edge at that time, and in the circumstances it was defensible."[104][105]

The "knife-edge" fate of the constitution was the justification for much else that was seen to define the unionist dispensation in Northern Ireland not only for nationalists but also, when forced again to attend to the Irish Question, for British opinion. The Royal Ulster Constabulary, the rump of the old RIC, was reinforced by a re-mobilised Special Constabulary. It was an almost entirely Protestant force, an excuse the nationalists alleged for arming Orangemen. A 1922 Special Powers Act gave the Northern Ireland Home Affairs Minister discretionary powers to direct the RUC and Specials as his agents in searches, arrests, detentions, and proscriptions. Despite of loyalist provocations these were directed almost exclusively at nationalists[106] (left-wing "agitators" were a target of later exclusion orders).[107] Unionists were to protest that such powers were no more controversial or divisive "than the existence of the Government itself", and less draconian than those the Dublin government had seen fit to exercise in defence of the Free State.[108]

The first extensive use of "special powers" followed the IRA assassination in May 1922 of the Unionist (NI) MP for West Belfast William J. Twaddell. A string of decrees followed: internment of 500 suspects, a province-wide curfew and flogging as "special punishment."[109] In 1922 in Northern Ireland a total of 232 people were killed, including four other Unionist MPs. Nearly a thousand were wounded.[110] The Civil War in the South drew away men, material and support for the IRA in the North. In 1925 Craig and the Southern premier William Cosgrave resolved the unsettling issue of border adjustment by agreeing to respect the county boundaries.

Unionists argue that the extent discrimination against Catholics was "absurdly exaggerated",[111] and that many Catholics preferred "second-class citizenship to working for the government".[112][113] But that there was Protestant preferment in public employment they acknowledge citing mitigating circumstances. The discrimination, they argue, was not one sided: few Protestants were employed by nationalist-controlled councils or indeed in Catholic-owned businesses. But ultimately they insist that "some element of preference [was] likely to be given to Protestants [because] so many Catholics withheld support from the state and were no unnaturally regarded as security risks."[114] Nationalists recall statements by Sir Edward Archdale, Northern Ireland's first Minister of Agriculture, "apologising that as many as 4 of 109 officials in his ministry were Catholics,"[115] and of the future prime minister Basil Brooke (Lord Brookeborough) labelling 97 per cent of Roman Catholics in Northern Ireland as "disloyal and disruptive."[116] No allowance was made for the reluctance of the minority to serve a "foreign" government. Loyalty oaths were required.

Stormont government

_-_geograph.org.uk_-_693330.jpg)

"The safety of the State" may have been, as Sir James Craig maintained, "the supreme law" in Northern Ireland.[117] But by the time the parliament had moved out of the Presbyterian Church's Assembly's College and into its new buildings at Stormont in 1932, "the state" was to outward appearances secure.

In 1932 unemployment had climbed to 28 percent. When the Belfast Board of Guardians refused assistance to many of the rapidly increasing number of applicants for Outdoor Relief, Catholics and Protestants joined in mass demonstrations that, accompanied by considerable disorder, secured a doubling of the relief. For many on left the victory kept alive "the hope that class — rather than national or sectarian — loyalties" might become a "decisive force in Irish politics"—hopes of a kind that, in the previous century, had centred on the struggle for tenant rights.[118] However, when in this expectation the Revolutionary workers Group (Communist Party of Ireland) took to the streets in 1935 they found themselves pushed aside in bitter sectarian rioting.[119] While the Outdoor Relief protests had expressed a measure of working-class disaffection with an "out-of-touch" Unionist leadership that spilled beyond control of the UUP's in-house Ulster Unionist Labour Association (UULA), it did not fundamentally alter "the expectations the Protestant masses had of 'their' state."[120]

Despite the efforts in the forties of such singular figures as writer and anti-conscription campaigner Denis Ireland, and the IRA "Protestant squad" leader John Graham, to "recapture for Ulster Protestants their true tradition as Irishmen,"[121] Protestants did not find occasion to revisit the "constitutional question." The Second World War "in many ways . . . strengthened and fulfilled unionist identification with Britain and by the same token hardened their attitude to their Catholic fellow citizens who had not, and could not have in their view, shared the experience of drawing together." At the same time the relative prosperity induced by wartime food and armaments production helped further "differentiate the North from the South" turning "citizenship in each of the part of Ireland into different experiences."[122]

For unionists, democracy in Northern Ireland effectively meant rule by one party. In his 28 years in Stormont (1925-1953) Tommy Henderson, a North Belfast independent ex-UULA, was a one-man unionist opposition. In the 1938 the Ulster Progressive Unionist Association attempted to join him, averaging a little better than a quarter of the vote in ten otherwise safe Government seats. After resolving positively for the Union, in 1953 the Northern Ireland Labour Party won three seats. But for the most part Government candidates were returned by unionist voters without contest. The Nationalist Party did not take their seats during the first Stormont parliament (1921–25), and did not accept the role of official Opposition for a further forty years.[123] Proclaimed by Craig a "Protestant parliament",[124] and with a "substantial and assured" Unionist-Party majority[125] the Stormont legislature could not, in any case, play a significant role. Real power "lay with the regional government itself and its administration": a structure "run by a very small number of individuals." Between 1921 and 1939 only twelve people served in cabinet, some continuously.[126]

Although they had no positive political programme for a devolved parliament, the Unionist regime did hazard an early reform. Consistent with the obligation under the Government of Ireland Act to neither establish nor endow a religion, a 1923 Education Act provided that in schools religious instruction would only be permitted after school hours and with parental consent. Lord Londonderry, as Minister of Education, owned that his ambition was mixed Protestant-Catholic education. In a reprise of the reception of Dublin-Castle National Schools proposal a century before, a coalition of Protestant clerics, school principals and Orangemen insisted on the imperative of bible teaching. Craig relented, amending the act in 1925. Meanwhile, the Catholic hierarchy refused to transfer any schools, and would not allow male Catholic student teachers to enrol in a common training college with Protestants or women.[127] In the North (as in the South) a pillar of sectarian division, the school-age segregation of Protestants and Catholics, was sustained.

In looking to the post-war future, the Unionist Government under Basil Brooke (Lord Brookeborough) did make two reform commitments. First, it promised a programme of "slum clearance" and public housing construction (in the wake of the Belfast Blitz the authorities acknowledged that much of the housing stock had been "uninhabitable" before the war). Second, the Government accepted an offer from London—understood as a reward for the province's wartime service—to match the parity in taxation between Northern Ireland and Great Britain with parity in the services delivered. What Northern Ireland might loose in autonomy, it was going to gain in a closer, more equal, Union. Since the Belfast government could not in any case control the tax implications, it seemed that they could only welcome British financial support for the public spending that would follow.[128]

By the 1960s Unionism was administering something at odds with the conservatism of those to whom leadership had been conceded in the resistance to Irish Home Rule. Under the impetus of the post-War Labour government in Britain, and thanks to the generosity of British exchequer, Northern Ireland had emerged with an advanced welfare state. The Education Act (NI), 1947, "revolutionised access" to secondary and further education. Catholic grant-aided schools were fully funded, and a school transfer test (the Eleven Plus) enabled qualifying students to receive a grammar-school education irrespective of background or circumstances. Health-care provision was expanded and re-organised on the model of the National Health Service in Great Britain to ensure universal access. The Victorian-era Poor Law, sustained after 1921, was replaced with a comprehensive system of social-security. Under the Housing Act (NI) 1945 the public subvention for new home construction was even greater, proportionately, than in England and Wales. The distinction between rural and urban housing was abolished, and local councils become housing authorities.[129]

1960s: reform and protest

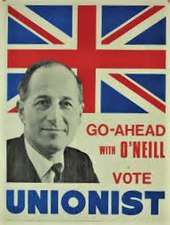

In the 1960s, under premiership of Terence O'Neill, Ulster Unionism was led through seeming economic-policy successes into a political crisis that upended the 1921 devolved constitution. A scion of a landed family (brought up partly in Abyssinia and partly at Eton) and, like all contenders for his position, a member of the Orange Order, O'Neill was the unlikely champion of a technocratic approach to government that was impatient with what he decried as "ancient hatreds."[130]

Recognising the decline of the province's Victorian-era industries, under O'Neill the Stormont administration intensified its efforts to attract outside capital. Investment in new infrastructure, training schemes coordinated with trade unions, and direct grants succeeded in attracting American, British and continental firms (some of these introducing into the one time linenopolis artificial fibres). In its own terms, the strategy was a success: the level of manufacturing employment was better than sustained. Yet Protestant workers and local Unionist leadership were unsettled. Unlike the established family firms and skilled-trades apprenticeships that had been "a backbone of unionism and protestant privilege," the new companies readily employed Catholics and women.[131]

Unionist unease was particularly acute in Derry and the west.[132] Already in 1956 O'Neill's predecessor, Lord Brookborough, had received a delegation "on industries" from Derry Unionists "anxious that we not get an invasion from the other side."[133] When Derry lost out to Coleraine for siting of the New University of Ulster, and to Lurgan and Portadown for a new urban-industrial development, some "from the other side" suspected a wider conspiracy. Speaking to Labour MPs in London, John Hume suggested that "the plan" was "to develop the strongly Unionist-Belfast-Coleraine-Portadown triangle and to cause a migration from West to East Ulster, redistributing and scattering the minority to that the Unionist Party will not only maintain but strengthen its position."[134]

Hume, a teacher from Derry, presented himself as a spokesman for an emerging "third force": a "generation of younger Catholics in the North" frustrated with a "flags and slogans" nationalism whose seeming indifference to "the general welfare of Northern Ireland" had made "the task of Unionist ascendancy simpler." Determined to engage the "great social problems of housing, unemployment and emigration", these new "political wanderers" were willing to acknowledge that "the Protestant tradition in the North is as strong and as legitimate" as their own (if "a man wishes Northern Ireland to remain part of the United Kingdom [that] does not necessarily make him a bigot or a discriminator") and that Irish unity, "if it is to come," could be achieved only "by the will of the Northern majority."[135] Although they appeared to meet Unionists half way, Hume and those who joined him in what he proposed would be "the emergence of normal politics" presented the Unionist government with a new challenge. Drawing on the struggle for black equality in the United States, they spoke a language of universal rights that had an international resonance far beyond that of the particularist claims of Irish nationalism.

Since 1964, the Campaign for Social Justice had been collating and publicising evidence of discrimination in employment and housing. From April 1967 the cause was taken up by the Belfast-based Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association, a broad labour and republican grouping with Communist Party veteran Betty Sinclair as chair. Seeking to "challenge . . . by more vigorous action than Parliamentary questions and newspaper controversy," NICRA decided to carry out a programme of marches.[136]

"Resembling a traditional nationalist parade" (complete with renditions of The Soldiers Song), the first march sponsored by NICRA in August 1968 into Dungannon went off comparatively peacefully. The second march was organised in October by the Derry Housing Action Committee. The march was to cross the River Foyle, from one side of Derry to the other "symbolising that the marchers were not sectarian,"[137] When a sectarian confrontation threatened—the Apprentice Boys of Derry announced their intention to march the same route—the NICRA executive was in favour of calling it off. But DHAC pressed ahead with activist Eamon McCann conceding that the "conscious, if unspoken strategy, was to provoke the police into overreaction and thus spark off mass reaction against the authorities.".[138] A later official inquiry suggests that, in the event (and as witnessed by three Westminster Labour MPs), all that had been required for police to begin "using their batons indiscriminately" was defiance of the initial order to disperse.[139] The day ended with street battles in Derry's Catholic Bogside area. For the first time in decades Northern Ireland was making British and international headlines, and television news.

Opposition to O'Neill

O'Neill had not disguised an ambition to bring the politics as well as the economy of Northern Ireland "into the twentieth century." In January 1965, at O'Neill personal invitation, the taoiseach Sean Lemass (whose government was pursuing a similar "modernising" agenda in the South) made an unheralded visit to Stormont. After O'Neill reciprocated with a visit to Dublin, the Nationalists were persuaded, for the first time, to assume the role at Stormont of Her Majesty's Opposition. With this and other conciliatory gestures (unprecedented visits to a Catholic hospitals and schools, flying the Union flag at half mast for the death of Pope John XXIII) O'Neill incurred the wrath of those he understood as "self-styled 'loyalists' who see moderation as treason, and decency as weakness,"[140] among these the Reverend Ian Paisley.

As Moderator of his own Free Presbyterian Church, and at a time when he believed mainline presbyteries were being led down a "Roman road" by the Irish Council of Churches, Paisley saw himself treading in the path of the "greatest son" of Irish Presbyterianism, Dr. Henry Cooke.[141] Like Cooke, Paisley was alert to ecumenicism "both political and ecclesiastical." After the Lemass meeting, Paisely announced that "the Ecumenists . . . are selling us out. Every Ulster Protestant must unflinchingly resist these leaders and let it be known in no uncertain manner that they will not sit idly by as these modern Lundies pursue their policy of treachery." Paisley had his own ideas of a "third force" in Ulster politics. He had been one of the founders of Ulster Protestant Action (UPA). Organised in 1956 to defend Protestant areas against anticipated Irish Republican Army (IRA) activity.[142][143] the UPA promoted and defended Protestant claims to housing and employment.[144][145]

Not only for the Paisleyites but for many within his own party O'Neills "policy of treachery" was confirmed when in December 1968 he sacked his hard-line Minister of Home Affairs, William Craig and proceeded with a reform package that addressed many of NICRA's demands. There was to be a needs-based points system for public housing; an ombudsman to investigate citizen grievances; the abolition of the rates-based franchise in council elections ("One man, one vote"); and The Londonderry Corporation was suspended and replaced by Development Commission. The Special Powers Act was to be reviewed.

At a Downing Street summit on 4 November, Harold Wilson had warned O'Neill that his government could not "tolerate a situation in which the liberalising trend was being retarded rather than accelerate," and that if that were the case they might "feel compelled to propose a radical course involving the complete liquidation of all financial agreement with Northern Ireland." The British Prime Minister muttered darkly about how, with British subsidy, the major Belfast employers, Shorts, the aircraft manufacturer, and Harland and Wolff, the shipyard, "had become a kind of soup kitchen."[146]

With members of his cabinet urging him to call Wilson's "bluff," and facing a Backbencher motion of no-confidence, in January 1969 O'Neill called a general election. Having reminded his television audience that under the Government of Ireland Act 1920 "the supreme authority of the Parliament of the United Kingdom [remained] unaffected and undiminished over all persons, matters and things" in Northern Ireland, O'Neill employed the talking points supplied by Wilson.

I make no apology for the financial and economic support we have received from Britain. As a part of the United Kingdom we have always considered this to be our right. But we cannot be a part of the United Kingdom merely when it suits us. And those who talk so glibly about acts of impoverished defiance do not know or care what is at stake. Your job if you are a worker at Shorts or Harland and Wolff; your subsidies if you are a farmer; your pension if you are retired; all these aspects of our life, and many others depend on support from Britain. Is a freedom to pursue the un-Christian path of communal strife and sectarian bitterness really more importent to you than all the benefits of the British Welfare state?[147]

O'Neill, who in Belfast personally canvassed Catholic households,[148] did not get from the traditional Unionist vote the answer he had sought. The UUP effectively split. "Pro-O'Neill" candidates picked up Liberal and Labour votes but won only a plurality of seats. In his own constituency of Bannside, from which he had previously been returned unopposed, the Prime Minister was humiliated by achieving only a narrow victory over Paisely standing as a Protestant Unionist. On 28 April 1969, O'Neill resigned.

O'Neill's position had been weakened when, focused on demands not conceded (redrawing of electoral boundaries, immediate repeal of the Special Power Act and disbandment of the Special Constabulary), republicans and left-wing students disregarded appeals from within NICRA and Hume's Derry Citizens Action Committee to suspend protest.[149] On 4 January 1969 People's Democracy marchers en route from Belfast to Derry were ambushed and beaten by loyalists, including off-duty Specials, at Burntollet Bridge[150][151] That night, there was renewed street fighting in the Bogside. From behind barricades, residents declared "Free Derry", briefly Northern Ireland's first security-force "no-go area".[152]

Tensions had been further heightened in the days before O'Neill's resignation when a number of explosions at electricity and water installations were attributed to the IRA. The later Scarman Tribunal established that the "outrages" were "the work of Protestant extremists . . . anxious to undermine confidence" in O'Neill's leadership.[153] (The bombers, styling themselves "the Ulster Volunteer Force," had announced their presence in 1966 with a series of sectarian killings).[154][155] The IRA did go into action on the night of 20/21 April, bombing ten post offices in Belfast in an attempt to draw the RUC away from Derry where there was again serious violence.[156]

O'Neill's parting judgement, bitterly contested by his critics who were convinced of the rising republican threat, typically focused on economic opportunity forgone: "We had all the benefits of belonging to a large economy, which were denied to the Republic of Ireland, but we threw it all away in trying to maintain an impossible position of Protestant ascendancy at any price".[157]

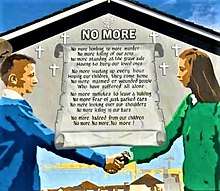

Unionist perspectives on The Troubles

All parties to the 1998 Good Friday Agreement dedicate themselves in its preamble to "the achievement of reconciliations, tolerance and mutual trust, and to the protection and vindication of the human rights of all." For many, particularly outside observers, the assumption was that the path to reconciliations, tolerance and mutual trust would run through the protection and vindication of rights. This rights-based perspective drew on what, internationally, proved to be the most compelling account of a conflict that over thirty years took more than 3,600 lives, and injured and bereaved many thousands more. This places at the heart of the conflict the movement for the "civil rights of the Catholic/Nationalist community."[158] It is the belief that many in that community came to support or acquiesce in the Republican return to "physical force" in 1970-71 because, in the words of Eamonn McCann, the notion that it was possible to achieve full citizenship within the North "was beaten out of people's heads by the cops and their semi-official auxiliaries."[159][160]

As an account of The Troubles, this is consistent with the broad support that the two main nationalist parties expressed for the provision in the Agreement for a possible Bill of Rights for Northern Ireland. As a party that "has its origins in the civil rights movement", Hume's Social Democratic and Labour Party (SDLP) maintained that it had "been a consistent voice [often the solitary voice] calling for effective protection of the human rights of all."[161] As the Provisional IRA began to explore a negotiated settlement with the British government, they too laid claim to the civil rights legacy. Already in the mid-1980s Sinn Féin President Gerry Adams was pointing to the involvement of the Wolf Tone Clubs in NICRA, and arguing that human rights had always been an integral part of the republican struggle.[162]

Given that it appears to extenuate the republican resort to terrorism, Unionists have tended to reject the civil-rights account of the Troubles in almost every particular. in the late 1960s Paisley was not alone is dismissing talk of civil rights as much "cant" behind which stood preparations for a renewed armed campaign. There was broad Unionist belief that the civil rights movement's demand for "simple justice" or, as was often presented in the metropolitan press, for "British standards", was "largely a charade," and that what was really "going on" was a "modern version of the old battle between nationalities."[163]

While they might concede "that several abuses of normal civil right did occur under the Stormont government", unionists argue that nationalists greatly exaggerated their impact upon the Catholic community.[164][165] Paul Kingsley's frequently cited "loyalist analysis of the Civil Rights controversy" maintains that, to the limited extent they occurred, the abuses protested by NICRA were as nothing compared to the profounder disadvantages for Catholic community represented by the nationalist policy of non-participation in public affairs ("much of the blame must fall on those who behaved as if they were not citizens at all")[166] and by the "structural" characteristics of low social status, of larger families and lower education attainment.[167][168]

The real interest behind the agitation for civil rights in Kingsley's account, is the social and political ambition of an emergent Catholic middle class (beneficiaries of the 1947 Education Act). Through the polemic of civil rights those who wished to pursue careers in law, public administration and elective office found release from the self-denying nationalist ordinances of non-recognition and abstention. They could represent themselves "as people who were heroically breaking down the barriers of discrimination: the promoters of Catholic group interests rather than traitors to the cause." "The political necessity to find a way to get the Catholic middle class into positions of influence," Kingsley argues, "meant that the discrimination argument had to be brought to the fore".[169]

If not from the outset, then by the summer of 1968 as republicans and left-wing militants took the initiative, "civil rights leaders" also came to realise the ability of their campaign "to convince the British government of the moral superiority of the Catholics position", and to "win changed which would be of symbolic importance." These in turn would "undermine Unionist self-confidence, and open the way for further demands".[170] On the street this was the calculation that urged a strategy of tension: provoking violent reactions from an ill-prepared police force and the "entirely predictable" and—Kingsley and other unionist commentators[171] allow--"ill disciplined" and "ferocious", intrusions into the picture of Protestant mobs, ever anxious to lend the authorities a hand in teaching "the rebels" a lesson. If inadvertently, the civil-rights agitation fostered the perceptions of deteriorating security and legitimacy that contributed not only to the introduction of British troops (August 1969) but also, over the course of 1970-71, to the ascendancy within IRA-Sinn Féin of an ultra-nationalist "Provisional" wing committed to a return to republicanism's "physical force" tradition.[172][173]

Unionists viewed the Provisionals' interpretation of physical-force republicanism as ruthlessly sectarian. Attacks on "Crown forces" and their supporting infrastructure, gave the Provisional IRA a broad field to target Protestants: locally recruited soldiers of the Ulster Defence Regiment/Royal Irish Regiment (successors to the Specials), members of the judiciary and prison services and base ancillary workers, suppliers and contractors. In border areas the policy was viewed as "ethnic cleansing", targeting Protestant farmers who, in the interest of community protection, were part-time members of the UDR-RIR, or who were seeking to buy land in what PIRA deemed to be "nationalist" territory.[174][175][176] Then there were the massacres such as Tullyvallen (an Orange hall), Darkley (a gospel hall), and Kingsmill (a labourers' bus) and the so-called "Baedeker raids", bombing "the heart out of small [largely Protestant] provincial towns", all an attempt "to break the spirit of the Unionist population."[177]

The charge that the Provisional IRA (PIRA) discriminated with religious bias, and that they actively targeted Protestant civilians has been broadly challenged. But it is allowed that "the PIRA were either unable or unwilling to recognise the gap between the actual impact of their 'armed struggle' and the intentions that lay behind it."[178]

Imposition of direct rule

To the extent they acknowledge inequities in Unionist rule from Stormont—in latter years, Paisley did allow "it wasn't . . a fair government. It wasn't justice for all"[179]—unionists argue that the responsibility ultimately lay with the failure of the government in London to acknowledge "their full and unequivocal membership of the United Kingdom."