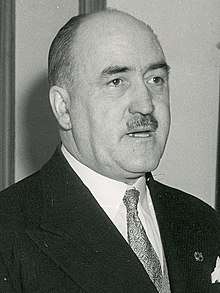

Frank Aiken

Francis Thomas Aiken (13 February 1898 – 18 May 1983) was an Irish revolutionary and politician who served as Tánaiste from 1965–1969, Minister for External Affairs from 1957 to 1969 and 1951 to 1954, Minister for Finance from 1945 to 1948, Minister for the Co-ordination of Defensive Measures 1939 to 1945, Minister for Defence from 1932 to 1939 and Minister for Lands and Fisheries from June–November 1936.

Frank Aiken | |

|---|---|

Aiken in 1944 | |

| Tánaiste | |

| In office 21 April 1965 – 2 July 1969 | |

| Taoiseach | |

| Preceded by | Seán MacEntee |

| Succeeded by | Erskine H. Childers |

| Minister for External Affairs | |

| In office 20 March 1957 – 2 July 1969 | |

| Taoiseach |

|

| Preceded by | Liam Cosgrave |

| Succeeded by | Patrick Hillery |

| In office 13 June 1951 – 2 June 1954 | |

| Taoiseach | Éamon de Valera |

| Preceded by | Seán MacBride |

| Succeeded by | Liam Cosgrave |

| Minister for Finance | |

| In office 19 June 1945 – 18 February 1948 | |

| Taoiseach | Éamon de Valera |

| Preceded by | Seán T. O'Kelly |

| Succeeded by | Patrick McGilligan |

| Minister for the Co-ordination of Defensive Measures | |

| In office 8 September 1939 – 18 June 1945 | |

| Taoiseach | Éamon de Valera |

| Preceded by | New office |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Minister for Defence | |

| In office 9 March 1932 – 8 September 1939 | |

| Taoiseach | Éamon de Valera |

| Preceded by | Desmond FitzGerald |

| Succeeded by | Oscar Traynor |

| Minister for Lands and Fisheries | |

| In office 3 June 1936 – 11 November 1936 | |

| Taoiseach | Éamon de Valera |

| Preceded by | Joseph Connolly |

| Succeeded by | Gerald Boland |

| Teachta Dála | |

| In office August 1923 – February 1973 | |

| Constituency | Louth |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Francis Thomas Aiken[1] 13 February 1898 Camlough, County Armagh, Ireland |

| Died | 18 May 1983 (aged 85) Blackrock, Dublin, Ireland |

| Resting place | Camlough, Armagh, Northern Ireland |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Political party | Fianna Fáil (from 1926) |

| Other political affiliations | Sinn Féin (1923–26) |

| Spouse(s) | Maud Aiken (1934–1978) |

| Children | 3 |

| Education | |

| Alma mater | University College Dublin |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Irish Volunteers Irish Republican Army |

| Years of service | 1914–1925 |

| Rank | Chief of Staff |

| Battles/wars | Irish War of Independence Irish Civil War |

He served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for the Louth constituency from 1923 to 1973. He was Chief of Staff of the Irish Republican Army. Originally a member of Sinn Féin, he was later a founding member of Fianna Fáil.[2]

Life

Early years

Aiken was born on 13 February 1898 at Carrickbracken, Camlough, County Armagh, Ireland, the seventh and youngest child of James Aiken, a builder from County Tyrone, and Mary McGeeney of Corromannon, Beleek, County Armagh. James Aiken built Catholic churches in South Armagh. Aiken was a nationalist, a member of the IRB and a county councillor, who refused an offer to stand as an MP. James was Chairman of the Local Board of the Poor Guardians. In 1900, on her visit to Ireland, he told Queen Victoria that he would not welcome her "until Ireland has become free."[3]

Frank Aiken was educated at the Camlough National School, and in Newry by Irish Christian Brothers at Abbey Christian Brothers Grammar School although he had only a 'vague' recollection of school. He was elected a lieutenant in 1914 when he joined the Camlough Company of Irish Volunteers and the Gaelic League. But the northern nationalists split so they took no part in the Easter Rising. He became secretary of the local branch in 1917, and joined Sinn Féin. His sister Nano Aiken organised Cumann na mBan in Newry, setting up a local branch at Camlough. While working at the Co-Operative Flax-Scutching Society, Aiken committed to speaking Irish which he learned at the Donegal Gaeltacht, Ormeath Irish College.

Activist and organiser

Aiken was elected Lieutenant of the local Irish Volunteers in 1917 (from 1919 better known as Irish Republican Army or IRA). He first met Eamonn de Valera at the East Clare election in June 1917, riding despatches for Austin Stack.[4] During a rowdy by-election at Bessbrook in February 1918, Aiken was elected a Captain of Volunteers, stewarding electioneering. As secretary and chairman of the South Armagh district executive (Comhairle Ceanntair) it was his job to be chief fund-raiser for the Dublin Executive, responsible for the Dáil loan masterminded by Michael Collins, the first to be issued by Dáil Éireann. The IRA units in South Armagh were more advanced than elsewhere in the north-east largely down to Aiken's leadership and training.[5] In 1917, making an outward display of defiance, Aiken raised the republican Irish tricolor, opposite Camlough Barracks in Armagh, a move designed as deliberate provocation.[6]

In March 1918 he was arrested by the RIC for illegal drilling; an act of open defiance that provoked a sentence of imprisonment for one month. On release that summer he joined the secretive Irish Republican Brotherhood fighting Hibernianism in the area. By 1919 Aiken's IRA activities mainly consisted of arms raids on dumps of the Ulster Volunteers who had imported weapons to resist Home Rule in 1913-14. As well as UVF dumps, Aiken and the Newry Brigade also raided prominent local unionist barracks at Dromilly, Ballyedmond Castle and Loughall Manor. Although they failed to capture many weapons the raids gave experience to newly recruited Volunteers.[7] Aiken was also responsible for setting up GAA Club, Gaelic League branch, a Cumann na mBan Camogie League.[8] At a sports event at Cullyhanna in June 1920, during the war of independence, Aiken led a group that demanded three RIC officers surrender their revolvers; shooting broke out killing one on each side. Within a few years he would become Chairman of the Armagh branch of Sinn Féin, and was also elected onto Armagh County Council.

Irish Republican Army involvement

War of Irish Independence

Aiken, operating from the south Armagh/north Louth area, was one of the most effective IRA commanders in Ulster during the Irish War of Independence. In May 1920 he led 200 IRA men in an attack on the Royal Irish Constabulary barracks in Newtownhamilton, assaulting the building and then burning it with paraffin spayed from a potato sprayer, though the police garrison did not surrender.[9] Aiken himself led a squad which blasted a hole in the wall of the barracks with gelignite and entered it, exchanging shots with the policemen inside.[10] In July, the new councillor was almost killed at Banbridge; while riding a motorcycle to Lurgan he was chased by an angry mob.[11]

In December 1920 he led another assault, this time abortive, on the RIC station in his home village of Camlough. In reprisal, the newly formed Ulster Special Constabulary burned Aiken's home and those of ten of his relatives in the Camlough area. They also arrested and killed two local republicans. From this point onward, the conflict in the area took on an increasingly bitter and sectarian quality. Aiken tried on a number of occasions to ambush USC patrols from the ruins of his family home.[12]

In April 1921, Aiken's IRA unit mounted an operation in Creggan, County Armagh to ambush the police and Special Constabulary. One Special was killed in the ensuing firefight. Some accounts have reported that Aiken took the Protestant Church congregation in the village hostage, to lure the Specials out onto the road.[13] But Mathew Lewis's televised account in 'Frank Aiken's War' implied that both Catholic and Protestant churchgoers were held in a pub to avoid the crossfire.[14]

Nevertheless sectarian bitterness deepened in the area. The following month, the Special Constabulary started shooting Catholic civilians in revenge for IRA attacks. In June 1921 Aiken organised his most successful attack yet on the British military, when his men derailed a train line under a British troop train heading from Belfast to Dublin, killing the train guard, three cavalry soldiers and 63 horses.[15] Shortly afterwards, the Specials took four Catholics from their homes in Bessbrook and Altnaveigh shooting them dead.

After an IRA reorganisation in April 1921, Aiken was put in command of the Fourth Northern Division of the Irish Republican Army.[16] The cycle of violence in south-east Ulster area continued the following year, despite a formal truce with the British from 11 July 1921. Michael Collins organised a clandestine guerrilla offensive against the newly created Northern Ireland State. In May 1922, for reasons that have never been properly determined, Aiken and his Fourth Northern Division never took part in the operation, although it was planned that they would. Aiken remained Head of the Ulster Council Command however. He was quickly promoted through the ranks, rising to Commandant of Newry Brigade and eventually commander of 4th Northern Division from the spring 1921. The IRA units he would eventually command extended from County Louth, southern and western County Down, and from March 1921 the whole of County Armagh.

Nonetheless the local IRA's inaction at this time did not end the bloodshed in South Armagh. Aiken has been accused by unionists of ethnic cleansing of Protestants from parts of South Armagh, Newry, and other parts of the north,.[17] In particular Aiken's critics cite the killing of six Protestant civilians, called the Altnaveigh Massacre on 17 June 1922.[18] The attack was in reprisal for the Special Constabulary's killing of three nationalists near Camlough on June 13 and the sexual assault of the wife of one of Aiken's friends. As well as the six civilians, two Special Constables were killed in an ambush and two weeks later a unionist politician named William Frazer was abducted, killed and the body secretly buried. It was not found until 1924.[19]

Irish Civil War

The IRA split over the Anglo-Irish Treaty of 1921 and this left Aiken ultimately aligned with the anti-Treaty side in the Irish Civil War in spite of personal efforts to prevent division and civil war. Aiken tried to remain neutral and after fighting broke out between pro- and anti-Treaty units in Dublin on June 28, 1922, he wrote to Richard Mulcahy on 6 July 1922 calling for a truce, the election of a new re-united IRA army council and the removal of the Oath of Allegiance from the Free State constitution.[20] Mulcahy was evasive however and said he 'could not see a way to advise the government' to agree with Aiken's proposals. Subsequently Aiken travelled to Limerick meet with anti-Treaty IRA leader Liam Lynch to urge him too to consider a truce in return for the removal of the British monarch from the constitution.[21]

Despite his pleas for neutrality and a negotiated end to the Civil War, Aiken was arrested by pro-Treaty troops on July 16, 1922, under Dan Hogan and imprisoned at Dundalk Gaol along with about 2-300 of his men.[22] After just ten days imprisonment, he was freed in a mass escape of 100 men from Dundalk prison on 28 July. Then, on 14 August, he led a surprise attack of between 300 and 400 anti-treaty IRA men on Dundalk. They blew holes in the army barracks there and rapidly took control of the town at a cost of just two of his men killed. The operation freed 240 republican prisoners seizing 400 rifles. While in possession of the town, Aiken publicly called for an end to the civil war. For the remainder of the conflict he remained at large with his unit, carrying out guerrilla assaults on Free State forces; however, Aiken was never enthusiastic about the internecine struggle.[23]

Ending the Civil War

Aiken was with IRA Chief of Staff Liam Lynch's patrol when they were ambushed at Knockmealdown, where the chief of staff was shot and killed. He rescued the IRA's papers "saved and brought through at any cost".[24] Aiken's reward was promotion in succession to Liam Lynch as IRA Chief of Staff in March 1923. Always ambivalent about the war against the Free State on becoming Chief of Staff, Aiken and the IRA Executive ordered a ceasefire or 'suspension of offensive operations on April 26, 1922. He remained close to Eamon de Valera, who had long wanted to end the Civil War, and together the two came up with a compromise that would save the anti-Treaty IRA from a formal surrender. Instead of giving up their weapons they would 'dump arms', ordering their fighters simply to return home as honourable republicans. Aiken wrote 'we took up arms to free our country and we'll keep them until we see an honourable way or reaching our objective without arms'.[25]

The cease-fire and dump-arms orders, issued on 24 May 1923 effectively ended the Irish Civil War, though the Free State government did not issue a general amnesty until the following year. Aiken remained Chief of Staff of the IRA until 12 November 1925. In the summer the anti-treaty IRA sent a delegation led by Pa Murray to the Soviet Union for a personal meeting with Joseph Stalin, in the hopes of gaining Soviet finance and weaponry assistance.[26] A secret pact was agreed whereby the IRA would spy on the United States and the United Kingdom and pass information to Red Army military intelligence in New York City and London in return for £500 a month.[26] The pact was originally approved by Aiken, who left soon after, before being succeeded by Andrew Cooney and Moss Twomey who kept up the secret espionage relationship.[26]

Founder of Fianna Fáil and government minister

Aiken was at the April 1925 Commemoration ceremony at Dundalk, but by March 1926—when De Valera founded a new party, Fianna Fáil—he was in America. Aiken was first elected to Dáil Éireann as a Sinn Féin candidate for Louth in 1923; in June 1927 he was re-elected there for Fianna Fáil, continuing to be re-elected for that party at every election until his retirement from politics fifty years later.[27] He entered the first Fianna Fáil government as Minister for Defence, later becoming Minister for the Co-ordination of Defensive Measures with responsibility for overseeing Ireland's national defence and neutral position during the Second World War (see The Emergency). In May 1926 he bought Dun Gaiothe, a dairy farm, at Sandyford, County Dublin. Aiken was an innovative, creative individual, an amateur inventor, taking out patents for a turf stove, a beehive, an air shelter, an electric cooker, and a spring heel for a shoe.[28]

Clash with the Governor General

Aiken became a source of controversy in mid-1932 when he, along with Vice-President of the Executive Council Seán T. O'Kelly publicly snubbed the Governor-General of the Irish Free State, James McNeill, by staging a public walkout at a function in the French legation in Dublin. McNeill privately wrote to Éamon de Valera, the President of the Executive Council, to complain at what media reports called the "boorishness" of Aiken and O'Kelly's behaviour. While agreeing that the situation was "regrettable" de Valera, instead of chastising the ministers, suggested that the Governor-General inform the Executive Council of his social engagements to enable ministers to avoid ones he was attending. Aiken had in March 1932 been trying to reach a new rapprochement, and "reconciled the Army to the new regime".[29] On 9 March he visited republican prisoners in Arbour Hill prison released the next day - he was given the vice-presidency Agriculture to James Ryan at the Ottawa Conference. He advised on the usage of cutting peat bogs in County Meath, and visited Curragh Camp to use the turf to accelerate land distribution to the poor tenantry. Land was released in 'the Midlands' for development.

When McNeill took offence at de Valera's response and against government advice, published his correspondence, De Valera formally advised King George V to dismiss the Governor General. The King arranged a special deal between both men, whereby McNeill would retire from his post a few weeks earlier than planned, with the resignation coinciding with the dates de Valera had suggested for the dismissal. On 25 April 1938, Aiken was too closely associated with the IRA to be allowed into the Anglo-Irish Agreement negotiations. Although the governor-generalship of the Irish Free State was controversial, the media and even anti-governor-generalship politicians in the opposition Labour Party publicly, and even members of de Valera's cabinet privately, criticised Aiken and O'Kelly for their treatment of McNeill, whom all sides saw as a decent and honourable man. Later in life Aiken refused to discuss the affair; but De Valera made amends by appointing Mrs McNeill as an Irish ambassador.

Minister for the Coordination of Defensive Measures and the Second World War

At the outbreak of war, Aiken was appointed to this post by de Valera. He gained notoriety in liberal Dublin circles for overseeing censorship: his clashes with R. M. Smyllie, editor of The Irish Times, ensured this censorious attitude was resented by many. Aiken not only corrected war coverage by the Irish Times, whose editorial line was largely pro-British, but also banned pro-allied war films and even forbade the reporting of parliamentarians' speeches that went against the government line of strict neutrality.[30] Aiken justified these measures, citing the 'terrible and all prevailing force of modern warfare' and the importance therein of morale and propaganda.[31]

Aiken remained opposed to a British role in Ireland and to partition of Ireland and was therefore a strong supporter of de Valera's policy of Irish neutrality, denying Britain use of Irish ports during the Battle of the Atlantic. Aiken considered that Ireland had to stand ready to resist invasion by both Germany and Britain. The Irish Army was therefore greatly expanded under Aiken's ministry, up to a strength of 41,000 regulars and 180,000 in auxiliary units the Local Defence Force and Local Security Force, by 1941, although these formations were relatively poorly equipped.[32]

Aiken wanted to incorporate the IRA into the Army and offered them an amnesty in the spring of 1940, which the underground organisation turned down.[33] Nevertheless, during wartime as the IRA cooperated with German intelligence, and pressed for a German landing in Northern Ireland, the government, with Aiken's approval, interned several hundred IRA members and executed six for the shooting of Irish police officers. Even so Aiken remained somewhat sympathetic to them in private, and visited their prisoners in Arbour Hill prison in Dublin, he did not appeal for clemency for those condemned to death.[34]

Thinking that Britain would lose the war in 1940, he refused to back senior British civil servant Malcolm MacDonald's plan for the unification of Ireland in return for the Irish state joining the British effort. In diplomatic negotiations Aiken told him that a united Ireland, if it was conceded, would still stay neutral to safeguard its security and that further talks were 'a sheer waste of time'. Furthermore the Irish people 'would not support their government taking them into the war without some actual provocation from Germany'.[35] When asked on American radio about the offer of unity in return for entering the war, he replied, 'most certainly not. We want union and sovereignty, not union and slavery'.[36]

In March 1941, Aiken was sent to America to secure US supplies, both military and economic, that Britain was withholding owing to Irish neutrality. Aiken had a bad tempered meeting with President Franklin Roosevelt in Washington DC. Roosevelt urged Aiken and Ireland to join the war on the allied side asking if it was true that he had said that 'Ireland had nothing to fear from a German victory'. Aiken denied saying this but cited the British 'supply squeeze' as an act of aggression and asked the US to help. Roosevelt agreed to send supplies only if Britain consented. At the close Aiken asked the President to 'support us in our stand against aggression'. 'German aggression, yes' Roosevelt replied, to which Aiken retorted 'British aggression too'. This infuriated Roosevelt, who shouted 'nonsense' and 'pulled the tablecloth [from under his lunch] sending cutlery flying around the room'.[37] Ultimately, Aiken was not able to secure a promise of American arms, but was able to get a shipment of grain, two merchant ships and coal. Roosevelt also gave 'his personal guarantee' that Britain would not invade Ireland.[38]

Minister for External Affairs

Aiken was Minister for Finance for three years following the war and was involved in economic post–war development in the industrial, agricultural, educational and other spheres. However, it was during his two periods as Minister for External Affairs—1951 to 1954, and 1957 to 1969—that Aiken fulfilled his enormous political potential. As Foreign Minister he adopted where possible an independent stance for Ireland at the United Nations and other international forums such as the Council of Europe. Despite a great deal of opposition, both at home and abroad, he stubbornly asserted the right of smaller UN member countries to discuss the representation of communist China at the General Assembly. Unable to bring the issue of the partition of Ireland to the UN, because of Britain's veto on the Security Council and unwillingness of other Western nations to interfere in what they saw as British affairs at that time (the US taking a more ambiguous position), Aiken ensured that Ireland vigorously defended the rights of small nations such as Tibet and Hungary, nations whose problems he felt Ireland could identify with and had a moral obligation to help.

Aiken also supported the right of countries such as Algeria to self-determination and spoke out against apartheid in South Africa. Under Ireland's policy of promoting the primacy of international law and reducing global tension at the height of the Cold War, Aiken promoted the idea of "areas of law", which he believed would free the most tense regions around the world from the threat of nuclear war.

The 'Aiken Plan' was introduced at the United Nations in an effort to combine disarmament and peace in the Middle East, Ireland a country being on good terms with both Israel and many Arab countries. In the UN the Irish delegation sat between Iraq and Israel forming a kind of physical 'buffer': in Aiken's time (who as a minister spent a lot of time with the UN delegation) both the Italians (who on their turn sat in the vicinity of the Iraqi delegation), the Irish and the Israelis claimed to be the one and only UN delegation of New York, a city inhabited by many Irish, Jewish and Italians. Aiken was also a champion of nuclear non-proliferation, for which he received the honour of being the first minister to sign the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty in 1968 at Moscow. Aiken's impact as Minister for External Affairs was such that he is sometimes referred to as the father of Irish foreign policy. His performance was praised in particular by a later Minister for Foreign Affairs, Fine Gael's Garret FitzGerald.

Quit politics over Charles Haughey

Aiken retired from Ministerial office and as Tánaiste in 1969. During the Arms Crisis it is said that the Taoiseach, Jack Lynch, turned to Aiken for advice on a number of issues. He retired from politics in 1973 due to the fact that Charles Haughey, whose style of politics Aiken strongly disliked, was allowed to run as a Fianna Fáil candidate in the 1973 general election. Initially he planned to announce the reason for his decision, but under pressure finally agreed to announce that he was retiring on medical advice.[39]

Refused candidacy for the presidency of Ireland

After his retirement the outgoing President of Ireland, Éamon de Valera, sought to convince Aiken—one of his closest friends—to run for Fianna Fáil in the 1973 presidential election. However, Aiken refused all requests to run and the party finally selected Erskine H. Childers to be its candidate. Childers won the election. In 1966, Aiken was appalled by the candidature of Charles Haughey, who was an open anti-partitionist.

When Jack Lynch, the Taoiseach and friend, announced his retirement, and future rise owed to Haughey, Aiken refused to serve. Haughey was a shrewd, but corruptible campaigner: running a gang of 500 businessmen out of Gresham's Hotel, Dublin to raise funds for his cause. Haughey's support for the Provisional IRA's bombing war was eventually exposed as in defiance of Aiken's warnings and persistent advice.[40]

Clash with Ernest Blythe

Shortly before his death, former Cumann na nGaedheal minister Ernest Blythe accused Aiken of rudely snubbing him in public throughout his political career. He said that, because of his support for the Treaty and Aiken's opposition, Aiken would pointedly turn his back on him whenever they came into contact.

Aiken's continuing bitterness towards Blythe was in contrast with the cross-party friendship which had developed between their colleagues Seán MacEntee (anti-treaty) and Desmond FitzGerald (pro-treaty) who, after the divide, re-established relationships and ensured their children held no civil war bitterness. The great rivals Éamon de Valera and W. T. Cosgrave, after years of enmity, also became reconciled in the 1960s. However Aiken refused to reconcile with former friends who had taken sides in the Civil War.

Family

In 1934 Aiken married Maud Davin, the director of the Dublin Municipal School of Music. The couple had three children: Aedamar, Proinnsias, and Lochlann.[41]

Death

Frank Aiken died on 18 May 1983 in Dublin from natural causes at the age of 85. He was buried with full State honours in his native Camlough, County Armagh, Northern Ireland.

Honours and memorials

Aiken received many decorations and honours, including honorary doctorates from the National University of Ireland and University College Dublin. He received the Grand Cross of St. Olav, the highest honour Norway can give to a foreigner, during a state visit to Norway in 1964.[42] He was also a lifelong supporter of the Irish language. His son, also named Frank, ran unsuccessfully in the 1987 and 1989 general elections for the Progressive Democrats. His wife died in a road accident in 1978.

Aiken Barracks in Dundalk, County Louth, now the headquarters of the 27 Infantry Battalionis named in his honour.

The extensive property owned by the Aiken family in the Lamb's Cross area of County Dublin (lying between Sandyford and Stepaside) has been transformed into the housing estate called Aiken's Village.

References

- "Frank Aiken - Family and Early Life, 1898-1921 | eoin magennis". Academia.edu. 1 January 1970. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Frank Aiken". Oireachtas Members Database. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- Matthew Lewis, Frank Aiken's War: The Irish revolution, 1916-1923, (Dublin: University College Dublin Press, 2014), 12

- M. Laffan, Resurrection of Ireland: The Sinn Fein Party, 1916-1923 (Cambridge: CUP, 1999), 94

- M. Lewis, 'The Newry Brigade at Independence War in Armagh and South Down,' Irish Sword XXVII (2010), 225-232; Eoin Magennis, Frank Aiken, 5.

- University College of Dublin Archive P104/1309, cited by Townshend in "The Republic", 32.

- Matthew Lewis, Frank Aiken's War, p.64-65

- C.Townshend, "The Republic: The Fight For Irish Independence" (London 2014), p.23.

- Matthew Lewis, Frank Aiken's War p67-72

- Lewis, Frank Aiken's War, p.90-91

- Newry Reporter, 23, 27 July 1920.; E. Magennis, Frank Aiken: Earl Life, 11.

- Lewis, Frank Aiken's War p.71-72

- Toby Harnden, Bandit Country, The IRA and South Armagh (1999), p/127-128

- Lewis, Frank Aiken's War, p.78-79

- "South Armagh History – The 4th Northern Division". Sinn Féin Cumann South Armagh. Archived from the original on 12 February 2008. Retrieved 19 April 2008.

- C. Townshend, "The Republic: The Fight For Irish Independence" (Penguin 2014), 457.

- "Families Acting for Innocent Relatives (FAIR)". Victims.org.uk. 8 February 2008. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "History Ireland". History Ireland. 17 June 1922. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- Pearse Lawlor, The Outrages p.298-300

- Lewis, Frank Aiken's War, p.174

- Lewis, Frank Aiken's War, p174-175

- The Irish Story, The Anti-Treaty attack on Dundalk

- Irish Dictionary of National Biography

- Florence O'Donoghue, "No Other Law" (Dublin, 1954, 1986), 305.

- Lewis, Frank Aiken's War, p197

- "The secret IRA–Soviet agreement, 1925". History Ireland. 8 February 2015.

- "Frank Aiken". ElectionsIreland.org. Retrieved 15 January 2011.

- Liam Skinner, 'Frank Aiken', in Politicians by Accident (Dublin: Metropolitan Publishing, 1946), 178; Tim Horgan, Dying for the Cause: Kerry's Republican dead (Mercier Press Ltd, 2015), 67-8.

- John Joseph Lee, Ireland: 1912-1985: Politics and Society, (Cambridge University Press, 1985), 176.

- Robert Fisk, In Time of War, Ireland, Ulster and the Price of Neutrality, 1939-1945, (Paladin, London, 1985) p.165-168

- Bryce Evans, 'The Iron Man with the Wooden Head'. Frank Aiken and the Second World War, in Bryce Evans and Stephen Kelly, (eds), Frank Aiken: Nationalist and Internationalist (Dublin, IAP, 2014)

- Evans, Frank Aiken, Nationalist And Internationalist, p.134-135

- Evans, Frank Aiken, p.135.

- Evans, Frank Aiken, p.137

- Robert Fisk, In Time of War, Ireland, Ulster and the Price of Neutrality, 1939-1945, (Paladin, London, 1985) p.204-206

- Evans, Frank Aiken, p.140

- Evans, Frank Aiken, p.141-142

- Evans, Frank Aiken, p.142

- Bruce Arnold, Jack Lynch: Hero in Crisis (Merlin Publishing, 2001) pp. 173-75.

- Stephen Kelly (24 June 2014). "The Haughey factor: why Frank Aiken really retired from party politics". Irishtimes.com. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- "Dictionary of Irish Biography - Cambridge University Press". dib.cambridge.org. Retrieved 29 June 2018.

- "First Irish State Visit to Norway 1964". RTÉ Archives. Retrieved 5 April 2014.

Bibliography

- Kelly, Dr. S & Evans, B, (eds.) Frank Aiken: Nationalist and Internationalist (Irish Academic Press, 2014)

- Bowman, J, De Valera and the Ulster Question 1917-1973 (Oxford 1982)

- Campbell, Colm, Emergency Law in England 1918-1925 (Oxford 1994)

- Cronin, S, The Ideology of the IRA (Ann Arbor 1972)

- Harnden, Toby, Bandit Country the IRA and South Armagh, Hodder & Staughton, (London 1999)

- Hart, P, The IRA at war 1916-1923 (London 2003)

- Henry, R.M, The Evolution of Sinn Fein (Dublin and London, 1920)

- Hepburn, A.C, Catholic Belfast and Nationalist Ireland in the era of Joe Devlin 1871-1934 (Oxford 2008)

- Hopkinson, Michael, The Irish War of Independence (Dublin and Montreal 2002).

- Lewis, Matthew, Frank Aiken's War, The Irish Revolution 1916-1923, UCD Press (Dublin 2014)

- Ni Dhonnchadha, Máirín and Dorgan, Theo (eds), Revising the Rising(Derry 1991).

- McCartan, Patrick, With de Valera in America (New York 1932)

- McDermott, J, Northern Divisions: The Old IRA and the Belfast Pogroms, 1920-22 (Belfast 2001)

- Phoenix, E, Northern Nationalism: Nationalist Politics, Partition and the Catholic minority in Northern Ireland 1890-1941 (Belfast 1994)

- Skinnider, Margaret, Doing My Bit For Ireland (New York 1917).

Further reading

- Matthew Lewis, Frank Aiken's War: The Irish Revolution, 1916-23 (2014)

- Bryce and Kelly, Frank Aiken: Nationalist and Internationalist (2014)

External links

- Frank Aiken Papers, Archives Department, University College Dublin

- Press Photographs from the Papers of Frank Aiken (1898–1983) A UCD Digital Library Collection.

| Oireachtas | ||

|---|---|---|

| New constituency | Teachta Dála for Louth 1923–1973 |

Succeeded by Joseph Farrell |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by Desmond FitzGerald |

Minister for Defence 1932–1939 |

Succeeded by Oscar Traynor |

| Preceded by Joseph Connolly |

Minister for Lands and Fisheries 1936 (acting) |

Succeeded by Gerald Boland |

| New office | Minister for the Co-ordination of Defensive Measures 1939–1945 |

Succeeded by Office abolished |

| Preceded by Seán T. O'Kelly |

Minister for Finance 1945–1948 |

Succeeded by Patrick McGilligan |

| Preceded by Seán MacBride |

Minister for External Affairs 1951–1954 |

Succeeded by Liam Cosgrave |

| Preceded by James Dillon |

Minister for Agriculture 1957 (acting) |

Succeeded by Seán Moylan |

| Preceded by Liam Cosgrave |

Minister for External Affairs 1957–1969 |

Succeeded by Patrick Hillery |

| Preceded by Seán Moylan |

Minister for Agriculture Nov. 1957 (acting) |

Succeeded by Paddy Smith |

| Preceded by Seán MacEntee |

Tánaiste 1965–1969 |

Succeeded by Erskine H. Childers |