Liberalism in Hong Kong

Liberalism has a long tradition in Hong Kong as an economic philosophy and has become a major political trend since the 1980s, often represented in the pro-democracy camp, apart from conservatism which often constitutes the pro-Beijing camp.

Although economic freedom was highly celebrated since the establishment of Hong Kong as a free trade port under British rule, several attempts at liberal reform received little success in the racially segregated and politically closed colony. However, many western-educated Chinese who were influenced by liberal thinkers became the most vocal reformists and revolutionaries in the late Qing dynasty period, including Ho Kai, Yeung Ku-wan and Sun Yat-sen. Reformist political groups also mushroomed in the early post-war period in response to Governor Mark Aitchison Young's proposed constitutional reform.

Liberal movements resurfaced again in the 1980s in the midst of the Sino-British negotiations over Hong Kong's sovereignty, where the liberals demanded for an autonomous democratic Hong Kong under Chinese rule. The liberals engaged in electoral politics when the colonial government carried out massive democratic reforms towards the end of colonial rule. The liberals won landslide victories in the last Legislative Council elections in 1991 and 1995.

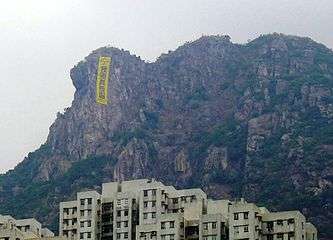

The influence of liberalism was curbed under the Chinese rule after 1997 due to the indirectly elected elements in the legislature. However, due to the unpopular Tung Chee-hwa administration in the first years of the SAR administration, the liberal movement regained its momentum after the historic 1 July demonstration against a restrictive law on national security, which was denounced by the liberals as an act of censorship. As the Beijing government tightened its grip on Hong Kong's society, the civil movements grew larger and more confrontational in the early 2010s. The 79-day occupy protests which were often referred to as the "Umbrella Revolution" broke out after the Beijing government's restrictive framework on the constitutional reform proposal gained international coverage.

19th to early 20th century

Laissez-faire liberalism

The cession of Hong Kong under the Treaty of Nanking in 1842 was overseen by then-British Foreign Secretary Lord Palmerston. Lord Palmerston was a prime figure of the Whig Party, which was the predecessor of the Liberal Party. The aims of the Opium War was to open up the Chinese market in the name of free trade. As the British free port of Hong Kong, taking advantage as the gateway to the vast Chinese market, Hong Kong merchants, the so-called compradors, had taken a leading role in investment and trading opportunities by serving as middlemen between the European and indigenous population in China and Hong Kong,[1] in the principles of laissez-faire classical liberalism, which has since dominated the economic discourse of Hong Kong.

Sir John Bowring, the Governor of Hong Kong from 1854 to 1859 and a disciple of liberal philosopher Jeremy Bentham for instance was a chief campaigner of free trade at the time. He believed that "Jesus Christ is free trade and free trade is Jesus Christ."[2] In 1858, Bowring proudly claimed that "Hong Kong presents another example of elasticity and potency of unrestricted commerce."[1] For that reason, Hong Kong has been rated the world's freest economy for the past 18 years, a title bestowed on it by the Heritage Foundation, a conservative Washington think tank,[3] and was greatly admired by libertarian economist Milton Friedman.[4][5]

Political liberalism

Compared to economic liberalism, political liberalism remained marginal in Hong Kong and did not gain much political influence. However, as the debate over Chinese modernisation got fiercer by the end of the 20th century, Hong Kong became the home of Chinese reformists and revolutionaries, namely Sir Ho Kai, who was inspired by classical liberal thinkers such as John Locke, Montesquieu, Adam Smith, Jeremy Bentham and John Stuart Mill.[6] He was an advocate of constitutional monarchy in China and a sympathiser of the revolutionary cause, along with his protegé, Dr. Sun Yat-sen, who had studied in Hong Kong and had stated that he got the inspiration for his revolutionary and modernist ideas from Hong Kong.[7]

One of the earliest revolutionary organisations, the Furen Literary Society, was set up in Hong Kong by Yeung Ku-wan in 1892. The society met in Pak Tsz Lane, in Central, Hong Kong, and released books and papers discussing the future of China and advocating the overthrow of the Qing dynasty and the establishment of a democratic republic in China. The society was later merged into the Revive China Society.

There were very few liberal reforms carried out by the colonial government towards the end of the 19th century. For instance, Sir John Bowring proposed that the elections to the Legislative Council should be based on property and not racial qualification. He believed that voting rights for the Chinese would "earn their support for the British government", which was strongly opposed by the local European community and the Colonial Office.[8]

Sir John Pope Hennessy, the Governor of Hong Kong from 1877 to 1893, was a liberal-minded governor who attempted to tackle the problem of racial segregation in the colony, but had received stiff resistance within the colonial establishment for his radical agenda.[9] Hennessy also proposed to abolish flogging as a form of punishment, which received widespread opposition from the European community, who even held a public protest meeting against his proposal.[10]

There were sporadic voices for political liberalisation in Hong Kong during the late 19th and early 20th century. One of the examples was the Constitutional Reform Association of Hong Kong, which was formed by the expatriate British business community in 1917. Headed by Henry Pollock and P. H. Holyoak, it submitted a proposal of introducing unofficial majority within the Legislative Council to the House of Commons of the United Kingdom, represented by member of parliament Colonel John Ward, but the proposal was ultimately rejected by the Colonial Office.[11] Failing to obtain any meaningful success for their proposals, the Constitutional Reform Association ceased to exist by October 1923.[12]

Post war years

Young Plan

The liberal movement experienced a resurgence following the return of British rule in 1945, after a 3 year long Japanese occupation of Hong Kong. Governor Mark Aitchison Young announced the plan for constitutional changes on the day of the return of the civil government in 1946, as "an appropriate and acceptable means of affording to all communities in Hong Kong an opportunity of more active political participation, through their responsible representatives, in the administration of the Territory."[13] It proposed to set up a municipal council which would give Hong Kong a limited degree of representative government.[14]

The Young Plan generated debates in the local community. Several political groups were set up to participate in the debate over political liberalisation, such as the Reform Club of Hong Kong, consisting mainly of the expatriate community, and the Hong Kong Chinese Reform Association, consisting of mostly Chinese citizens in 1949. After the Young Plan was eventually shelved in 1952, the Chinese community strongly protested and demanded immediate constitutional reforms. The Reform Club, along with the Hong Kong Civic Association set up in 1954, were the closest to opposition parties in Hong Kong during the post-war colonial period which participated in the Urban Council elections.

Self-government movement

The call for liberalisation and sovereignty continued in the 1950s and 1960s. The United Nations Association of Hong Kong (UNAHK), formed by Ma Man-fai in 1953, demanded sovereignty in Hong Kong. In a proposal drafted in 1961, the association laid out a plan for an ultimately fully direct election for the Legislative Council, which in that period was appointed by the governor. The Reform Club and the Civic Association also formed a coalition in 1960 and sent a delegate to London to demand fully direct elections to the Legislative Council and universal suffrage, but failed to negotiate any meaningful reforms.

The self-proclaimed "anti-communist" and "anti-colonial" Democratic Self-Government Party of Hong Kong was set up in 1963, calling for a fully independent government in which the Chief Minister would be elected by all Hong Kong residents, while the British government would only preserve its power over diplomacy and military.[15]

There were also the Hong Kong Socialist Democratic Party and the Labour Party of Hong Kong, which took a more left-leaning and democratic socialist approach to Hong Kong's independence and decolonization. In 1966, Urban Councillor Elsie Elliott, who was also member of the UNAHK, visited London and met with British government officials and Members of Parliament, asking for constitutional reform towards sovereignty, a reform of the judiciary towards impartiality and equal representation, and comprehensive anti-corruption investigations of the colonial nomenklatura and legal authorities. After once again failing to obtain any successful concessions, all the parties advocating for the sovereignty of Hong Kong ceased to exist by the mid-1970s.

Positive non-interventionism

Economic liberalism and free-market capitalism remained the dominant economic philosophy in Hong Kong throughout its history. In 1971, Financial Secretary John Cowperthwaite coined the term "positive non-interventionism", which stated that the economy was doing well in the absence of government intervention and excessive regulation, but it was important to create the regulatory and physical infrastructure to facilitate market-based decision making. This policy was continued by subsequent Financial Secretaries, including Sir Philip Haddon-Cave, who said that "positive non-interventionism involves taking the view that it is usually futile and damaging to the growth rate of an economy, particularly an open economy, for the Government to attempt to plan the allocation of resources available to the private sector and to frustrate the operation of market forces", although he stated that the description of Hong Kong as a laissez-faire society was "frequent but inadequate".

The economic philosophy was highly praised by economist Milton Friedman, who wrote in 1990 that the Hong Kong economy was perhaps the best example of a free market economy.[5] Right before he died in 2006, Friedman wrote the article "Hong Kong Wrong – What would Cowperthwaite say?" in the Wall Street Journal, criticizing Donald Tsang, the Chief Executive of Hong Kong who had the slogan of "big market, small government," where small government is defined as less than 20% of GDP, for abandoning the doctrine of "positive non-interventionism."[16]

1970s student movements

The 1970s in Hong Kong were the prime years of socially liberal student movements. Although the student unions were all dominated by the Chinese nationalists which were largely inspired by the Cultural Revolution and personality cult of Mao Zedong in Mainland China at the time, a liberal cabinet led by Mak Hoi-wah and assisted by Albert Ho won the 1974 election of the Hong Kong University Students' Union (HKUSU). The liberals held slightly Chinese nationalist sentiments but strongly opposed the blind-eyed pro-Communist nationalist discourse and stressed caring for the Hong Kong society and its citizens. Many of them also opposed colonial rule. They participated in social movements, such as the Chinese Language Movement, the anti-corruption movement, the Baodiao movement and so on, in which many of the student leaders became the main leaders of the contemporary pro-democracy movement.

The rise of the pro-democracy camp

In the early years of the 1980s, Hong Kong politics were dominated by the issue of the sovereignty of Hong Kong after 1997. Deng Xiaoping, the paramount leader of the Chinese Communist government, insisted China shall rule Hong Kong, while the British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher insisted that the legality of the Treaty of Nanking must be upheld. Some Hong Kong liberal intellectuals saw it as an opportunity to change the colonial status quo to a democratic and fairer society. This view was held by Tsang Shu-ki, a prominent thinker in the social activist circle at the time. In January 1983, the liberals forming the Meeting Point favoured Chinese rule with the slogan of the new Three Principles of People, "Nation, Democracy and People's Livelihood." It became one of the earliest groups in Hong Kong that favoured Chinese sovereignty over Hong Kong, but they also wanted a free, democratic and autonomous Hong Kong.[17]

The Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984 guaranteed Hong Kong would retain a high degree of autonomy under Chinese rule with the preservation of the maintained Western lifestyle in Hong Kong.[18] Deng Xiaoping also emphasised the principle of "Hong Kong's people ruling Hong Kong." Starting from 1984, the colonial government began to gradually introduce representative democracy into Hong Kong. The reform proposals were first carried out in the Green Paper: the Further Development of Representative Government in July 1984 which allowed 24 seats in the Legislative Council to be indirectly elected by electoral college.[19] Direct elections were also introduced at the district and municipal levels.

During the period, many liberal political groups were formed to contest the elections in different levels. By the late 1980s, the Meeting Point led by Yeung Sum, the Hong Kong Affairs Society led by Albert Ho formed in 1985, and the Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People's Livelihood (HKADPL) led by Frederick Fung became the three major liberal political forces active in electoral politics.

The liberals also formed the Joint Committee on the Promotion of Democratic Government (JCPDG) to demand a faster pace of democratisation and to introduce direct elections in the 1988 Legislative Council.[20] It was led by the two most prominent liberal icons, Martin Lee and Szeto Wah, who were also appointed by Beijing into the Hong Kong Basic Law Drafting Committee (BLDC), to draft the provisional constitution of the Hong Kong government after 1997. The liberal demands faced strong opposition from the conservative coalition of the business elites and the pro-Communist Beijing-loyalists.[21] In the BLDC, the liberal faction, the Group of 190 also faced the conservative Group of 89, who favoured a less democratic system after 1997.

Tiananmen protests and the tide of democracy

The liberals supported the democratic cause of the Tiananmen protests of 1989 and formed the Hong Kong Alliance in Support of Patriotic Democratic Movements in China (HKASPDMC). They were shocked by the bloody crackdown on 4 June 1989. Martin Lee and Szeto Wah resigned from the BLDC as an act of protest against the Beijing government after the massacre and the relationship between Beijing and pro-democrats severely deteriorated. The democrats have held the Annual Tiananmen vigil since then and called for the end of one-party rule in China. The pro-democrats became sharply anti-Beijing while the Beijing government accused the liberals of "treason".

The widespread fear among the Hong Kong public also helped the rise of the pro-democracy camp. The liberals formed the United Democrats of Hong Kong (UDHK) in 1990 as the first major political party in Hong Kong's history. The UDHK and Meeting Point alliance and other pro-democratic independents including Emily Lau swept the votes in the first direct elections of the Legislative Council in 1991, by winning 16 of the 18 direct elected seats. To counter the liberal rise in the legislature, the conservative business elites formed the Liberal Party in 1993 which positioned itself as economically liberal and politically conservative.

The arrival of the last governor Chris Patten, the former chairman of the British Conservative Party also brought huge political changes in Hong Kong. Despite Beijing's strong opposition, he put forward the much more liberal constitutional reform proposals to enfranchise 2.7 million new voters and lower the voting age from 21 to 18.[22] Safeguarded by the liberal majority, the Patten proposals were passed in the Legislative Council after unprecedented political wrangling.

In the substantially more democratic elections in 1995, the Democratic Party, formed out of the merger of the United Democrats and the Meeting Point movement received another landslide victory, winning half of the Legislative Council seats. Many liberal pieces of legislation were able to pass in the last years of colonial rule, such as the Hong Kong Bill of Rights Ordinance. At the time, there were also new liberal parties being set up, such as the radical The Frontier, led by Emily Lau, and the Citizens Party, led by Christine Loh.

In response to the Patten proposals, the Beijing government set up the Provisional Legislative Council (PLC) which was seen as unconstitutional by the pro-democrats. The pro-democrats, except for the HKADPL, boycotted the PLC and stepped down as legislators during the last days of colonial rule. The pro-democrats ran again in the first legislative elections of the SAR period. Although the pro-democrats continuously received about 60% of the popular vote in every election held since 1997, their influence was contained and hampered by the indirectly elected trade-based functional constituencies.

1 July 2003 protest and further struggle for universal suffrage

Since the handover of Hong Kong, constitutional reform remained the dominant political agenda and goal of the liberals. The Hong Kong Basic Law Article 45 promised that "the ultimate aim is the election of the Chief Executive (CE) by universal suffrage" while Article 68 stipulated that "the ultimate aim is the election of all members of the Legislative Council (LegCo) by universal suffrage". Pro-democratic politicians and activists demanded an early implementation of universal suffrage for the CE and LegCo elections from the beginning.[23] The pro-democrats launched a protest on 1 July, the establishment day of the Special Administrative Region (SAR) to call for the implementation of universal suffrage and the abolishing of the functional constituencies.

The Democratic Party, the flagship liberal party of Hong Kong, suffered intra-party conflicts in the late 1990s, as the left-leaning pro-grassroots "Young Turks" challenged the leadership and subsequently left the party. It formed the Social Democratic Forum, who held a more social democratic and working-class stance on economics and social matters, and later joined The Frontier.

In 2002, the Tung Chee-hwa administration proposed legislation enforcing Hong Kong Basic Law Article 23, an anti-subversion law. The liberals feared the proposed legislation would undermine the civil liberties of Hong Kongers, and several legal professionals formed the Hong Kong Basic Law Article 23 Concern Group and raised their concerns over the legislation. Protests against the national security bill resulted in a massive demonstration held on July 1, 2003.

An estimated 350,000 to 700,000 people (out of the total population of 6,730,800 Hong Kongers) demonstrated against the bill, as well as the failing economy, the government's handling of the SARS epidemic, and the unpopular administration of Chief Executive Tung Chee-hwa and Secretary for Security Regina Ip, who was responsible for the creation of the bill. The only protests held in Hong Kong larger than this one were the gatherings contemporarily supporting and commemorating the 1989 Tiananmen square protests, and the 2019 Hong Kong protests against the Hong Kong extradition bill.[24][25]

On 26 April 2004, the National People's Congress Standing Committee (NPCSC) issued a verdict stating that the elections of the 2007 CE and 2008 LegCo will not be decided by universal suffrage, thereby defeating the democrats' appeal for universal suffrage by 2007–2008.[26] The popularity of the liberal forces rebounded after the massive demonstration held on July 1, 2003. In the 2004 Legislative Council election, the Article 23 Concern Group, having renamed itself to the Article 45 Concern Group, had all four of its candidates elected onto the LegCo.

In 2005, Tung Chee-hwa resigned due to ill health and was replaced by Chief Secretary for Administration Donald Tsang. The Tsang administration put forward the Fifth Report constitutional reform proposals, but were turned down by the pro-democrats, who thought it was an insufficient half-measure which did not actually implement democracy within Hong Kong.

In March 2006, the Article 45 Concern Group transformed itself into the Civic Party, which became the second largest liberal party behind the Democratic Party. In October of that same year, the former leaders of the social democratic faction of the Democratic Party, Andrew To and former Trotskyist Leung Kwok-hung, also known as "Longhair", founded the League of Social Democrats (LSD) with Albert Chan and former popular radio host Wong Yuk-man, which positioned itself as a radically pro-democratic and left-wing party.

In the 2007 Hong Kong Chief Executive election, Alan Leong of the Civic Party successfully entered the race against the incumbent Chief Executive Donald Tsang. As the Chief Executive was elected by the 800-member Election Committee which was tightly controlled by Beijing officials, Alan Leong ultimately lost to Donald Tsang, receiving only 15% of the electoral votes.

In December 2007, the NPCSC once again ruled out universal suffrage for the Chief Executive and LegCo elections, but stated that the 2017 Chief Executive election may be held with universal suffrage.[27]

Five Constituencies Referendum and the 2010 great split

In 2009, when the government carried out the constitutional reform proposals for the 2012 Chief Executive and LegCo elections, the League of Social Democrats suggested the "Five Constituencies resignation" proposal to pressure the government to implement universal suffrage by having pro-democratic legislators resign in each constituency and run for the successive by-elections in order to initiate a de facto referendum on democracy, the functional constituencies, and universal suffrage. The proposal was rejected by the Democratic Party and the moderate Alliance for Universal Suffrage, who instead sought to engage in peaceful negotiations with Beijing, and officially split with the Civic Party and the League of Social Democrats, fostering discontent from the supporters of the resignation plan.

In June 2010, the moderate democrats held a secret meeting with the central government representative in the central government's liaison office, which was the first meeting between Beijing representatives and pro-democratic politicians since the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre.[28] The central government subsequently accepted the Democratic Party's modified proposals to allow ten new seats to be directly elected by Hong Kongers. The Democrats' move was seen as an "act of betrayal" by the radical pro-democrats. In the 2011 District Council election, the radical People Power movement split from the League of Social Democrats and ran against the established Democratic candidates in order to "punish" the Democratic Party for their overtures towards Beijing. The intensifying split between the moderates and radicals saw the emergence of localism in Hong Kong during the early 2010s.

Umbrella Revolution and aftermath

In 2013, legal scholar Benny Tai proposed an act of civil disobedience carried out in Central, Hong Kong to put pressure on the government if its universal suffrage proposals proved to be "fake" democracy.[29] The Occupy Central with Love and Peace (OCLP) demanded that the government proposal should satisfy the "international standards" in relation to universal suffrage with no unreasonable restrictions on the right to stand for election. It also said that any civil disobedience should be non-violent,[30] although it cannot guarantee Occupy Central will be absolutely peaceful.[31]

On 31 August 2014, the NPCSC of the set limits for the 2017 Chief Executive election. While notionally allowing for universal suffrage, the candidate would need to be nominated by a nominating committee, mirroring the present Beijing-controlled 1200-member Election Committee and must receive the support of more than half of the members of the nominating committee.[32]

In response to the NPCSC decision, the OCLP announced that it would organise civil disobedience protests.[33] The Hong Kong Federation of Students and Scholarism mobilised students and staged a coordinated class boycott. At the same time, Scholarism organised a demonstration outside of the Central Government Offices barricade on 13 September where they declared a class-boycott on 26 September.[34] On 26 September night, up to 100 protesters led by Joshua Wong, convenor of Scholarism, clambered over the fence of the square in the Central Government Offices.[35] The police clearance of the protesters in the square drew more protesters to the scene and eventually escalated to the 79-day massive sit-in. The protests precipitated a rift in Hong Kong society, and galvanised youth, a previously apolitical section of society, into political activism or heightened awareness of their civil rights and responsibilities. The protests ended without any political concessions from the government.

After the 2014 Hong Kong protests, there were a group of young generation new faces participated in the 2015 District Council elections which were loosely labelled as "umbrella soldiers" with mixed localist factions. They had a better-than-expected results with eight of them managed to win a seat by beating some incumbents.[36] In April 2016 ahead of the 2016 Legislative Council election, the former student leaders Joshua Wong and Nathan Law in the 2014 Occupy protests announced the formation of a new party called Demosistō advocating a referendum to determine Hong Kong's sovereignty after 2047, when the One Country, Two Systems principle as promised in the Sino-British Joint Declaration and the Hong Kong Basic Law is supposed to expire.[37] Barred from running in the election due to the age limit, Demosistō only filled one ticket in Hong Kong Island where chairman Nathan Law was elected. Together with other activists Lau Siu-lai and Eddie Chu under the banner of "democratic self-determination", they took away about seven percent of the total votes and gained three seats, while older generation of democrats including Emily Lau, Alan Leong and Albert Ho chose to step down.

As a result of the Legislative Council oath-taking controversy and the National People's Congress Standing Committee's interpretation of the Basic Law, four pro-democrat legislators, Leung Kwok-hung, Nathan Law, Lau Siu-lai and Yiu Chung-yim were disqualified from the office in July 2017, following the two localist Youngspiration legislators Baggio Leung and Yau Wai-ching were disqualified earlier, over their behaviours during the oath-taking ceremony in which the court deemed as invalid.[38] Shortly afterwards on 17 August, three main leaders in the Occupy protests Joshua Wong, Alex Chow and Nathan Law were given prison sentences for storming the forecourt of the Central Government Complex on 26 and 27 September 2017. 13 other activists who stormed the Legislative Council Complex were also handed prison sentences during the protest against the planned North East New Territories new towns few days before.[39][40]

List of liberal parties

Meeting Point

- 1983: Formation of the Meeting Point

- 1990: Members of the group formed the ⇒ United Democrats of Hong Kong

- 1994: The party merged into the ⇒ Democratic Party

- 2002: Anthony Cheung of the Democratic Party left and formed think tank ⇒ SynergyNet

- 2015: Tik Chi-yuen of the Democratic Party left and formed ⇒ Third Side

Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People's Livelihood

- 1986: Formation of the Hong Kong Association for Democracy and People's Livelihood

- 1990: Members of the group formed the ⇒ United Democrats of Hong Kong

- 1996: The radical faction left and formed the ⇒ Social Democratic Front

Hong Kong Democratic Foundation

- 1989: Formation of the Hong Kong Democratic Foundation

- 1992: Leong Che-hung of the group joined the ⇒ Meeting Point

United Democrats to Democratic Party

- 1990: The liberals united in the United Democrats of Hong Kong

- 1994: The Meeting Point merged into the ⇒ Democratic Party

- 2000: The left-wing faction left and formed the ⇒ Social Democratic Forum

- 2008: The Frontier merged into the ⇒ Democratic Party

- 2010: The young Turks left and formed the ⇒ Neo Democrats

- 2015: The moderate faction left and formed the ⇒ Third Side

Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions

- 1990: Hong Kong Christian Industrial Committee formed the Hong Kong Confederation of Trade Unions

- 2012: The union formed the ⇒ Labour Party

Democratic Alliance

- 1994: Pro-Taiwan politicians formed 123 Democratic Alliance

- 2000: The party was dissolved

- 2003: Former members formed Yuen Long Tin Shui Wai Democratic Alliance

- 2011: The Democratic Alliance formed alliance with the ⇒ People Power

- 2012: The Democratic Alliance broke away from the People Power

The Frontier

- 1996: The United Ants formed the Frontier

- 2003: Cyd Ho of the group formed the ⇒ Civic Act-up

- 2006: The social democratic faction left and formed the ⇒ League of Social Democrats

- 2008: The party merged into the ⇒ Democratic Party

- 2010: The radical faction re-registered the party

- 2011: The party formed alliance with the ⇒ People Power

- 2016: The party broke away from the People Power

Citizens Party

- 1997: Formation of the Citizens Party

- 2008: The party was dissolved

Article 23 Concern Group to Civic Party

- 2002: Formation of the Article 23 Concern Group

- 2003: The group renamed to the ⇒ Article 45 Concern Group

- 2006: The group transformed into the ⇒ Civic Party

- 2008: Fernando Cheung left the party and later formed the ⇒ Labour Party

- 2015: Ronny Tong left the party and formed the think tank ⇒ Path of Democracy

- 2016: Claudia Mo left the party and represented ⇒ HK First

Civic Act-up

- 2003: Cyd Ho formed the Civic Act-up

- 2012: The group formed the ⇒ Labour Party

League of Social Democrats

- 2006: Formation of the League of Social Democrats

- 2011: Members of the party left and formed the ⇒ People Power

Neo Democrats

- 2010: Formation of the Neo Democrats

People Power

- 2011: Formation of the People Power

- 2012: Wong Yeung-tat left along with the ⇒ Civic Passion

- 2013: Wong Yuk-man left along with the ⇒ Proletariat Political Institute

Labour Party

- 2012: Formation of the Labour Party

Demosistō

- 2016: Formation of Demosistō

Liberal figures and organisations

See also

Other ideologies in Hong Kong

References

- Ngo, Tak-Wing (2002). Hong Kong's History: State and Society Under Colonial Rule. Routledge. p. 30. ISBN 1134630948.

- Hoppen, K. Theodore (2000). The Mid-Victorian Generation, 1846-1886. Clarendon Press. p. 156. ISBN 019873199X.

- Hunt, Katie (12 January 2012). "Is Hong Kong really the world's freest economy?". BBC.

- Ingdahl, Waldemar (22 March 2007). "Real Virtuality". The American. Archived from the original on 3 October 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- Friedman, Milton; Friedman, Rose (1990). Free to Choose: A Personal Statement. Harvest Books. p. 34. ISBN 0-15-633460-7.

- Chan, Ming K.; Young, John D. (2015). Precarious Balance: Hong Kong Between China and Britain, 1842-1992. Routledge.

- "Sun's Address at HKU, 1923". The University of Hong Kong.

- Bowring, Philip (2014). Free Trade's First Missionary: Sir John Bowring in Europe and Asia. Hong Kong University Press. p. 164. ISBN 9888208721.

- Tsang, Steve (2007). A Modern History of Hong Kong: 1841-1997. I.B.Tauris. p. 66. ISBN 0857730835.

- Chu, Cindy Yik-yi (2005). Foreign Communities in Hong Kong, 1840s-1950s. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 46. ISBN 1403980551.

- Tsang, Steve Yui-Sang (1995). A Documentary History of Hong Kong: Government and Politics. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 79–81.

- Miners, Norman (1987). Hong Kong under Imperial Rule, 1912-1941. Oxford University Press. p. 138.

- Tsang, Steve Yui-sang (1995). Government and Politics. Hong Kong University Press. pp. 121–2. ISBN 9622093922.

- Tsang, Steve Yui-sang (1995). Government and Politics. Hong Kong University Press. p. 122. ISBN 9622093922.

- 貝加爾 (2014). "馬文輝與香港自治運動" (PDF). 思想香港 (3).

- Friedman, Milton (6 October 2006). "Dr. Milton Friedman". Opinion Journal. Archived from the original on 6 October 2006. Retrieved 20 February 2008.

- Scott, Ian. Political Change and the Crisis of Legitimacy in Hong Kong. University of Hawaii Press. p. 210.

- Tucker, Nançy Bernkopf (2001). China Confidential: American Diplomats and Sino-American Relations, 1945–1996. Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231106306.

- The Hong Kong Government (1984). Green Paper: The Further Development of Representative Government in Hong Kong. Hong Kong: Government Printer. p. 3.

- Béja, Jean-Philippe (2011). The Impact of China's 1989 Tiananmen Massacre. Taylor & Francis. pp. 186–187.

- Loh, Christine (2010). Underground Front: The Chinese Communist Party in Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. p. 164.

- Loh, Christine (2010). Underground front. p. 181.

- Fong, Brian C. H. (2014). Hong Kong’s Governance Under Chinese Sovereignty: The Failure of the State-Business Alliance After 1997. Routledge. p. 43.

- Williams, Louise; Rich, Roland (2000). Losing Control: Freedom of the Press in Asia. Asia Pacific Press. ISBN 0-7315-3626-6.

- "A historic day in Hong Kong concludes peacefully as organisers claim almost 2 million people came out in protest against the fugitive bill". South China Morning Post. 16 June 2019. Retrieved 6 October 2019.

- Fong, Brian C. H. (2014). Hong Kong’s Governance Under Chinese Sovereignty: The Failure of the State-Business Alliance After 1997. Routledge. p. 43.

- Decision Of The Standing Committee Of The National People's Congress On Issues Relating To The Methods For Selecting The Chief Executive Of The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region And For Forming The Legislative Council Of The Hong Kong Special Administrative Region In The Year 2012 And On Issues Relating To Universal Suffrage (Adopted By The Standing Committee Of The Tenth National People's Congress At Its Thirty-First Session On 29 December 2007), Hong Kong Legal Information Institute Archived 2008-12-23 at the Wayback Machine

- "Reform on agenda as alliance readies for talks with Beijing". The Standard. 17 March 2010. Archived from the original on 29 June 2011.

- "公民抗命的最大殺傷力武器". Hong Kong Economic Journal. Retrieved 27 March 2013.

- "OCLP Manifesto". Archived from the original on 30 September 2014. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- "Occupy Central is action based on risky thinking". The Standard. Archived from the original on 12 September 2014.

- "Full text of NPC decision on universal suffrage for HKSAR chief selection". Xinhua News Agency. 31 August 2014. Archived from the original on 19 January 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2014.

- Buckley, Chris; Forsythe, Michael (31 August 2014). "China Restricts Voting Reforms for Hong Kong". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015.

- "學民思潮發動926中學生罷課一天". RTHK. 13 September 2014. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015.

- Jacobs, Harrison (27 September 2014). "REPORT: Hong Kong's 17-Year-Old 'Extremist' Student Leader Arrested During Massive Democracy Protest". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015.

- Cheung, Tony (23 November 2015). "Hong Kong district council elections: the top 4 surprises and what they mean to the future of politics in the city". South China Morning Post.

- "Mission". Demosistō. Archived from the original on 20 January 2017. Retrieved 4 November 2017.

- "Four More Hong Kong Lawmakers Ousted In a Blow to Democratic Hopes". TIME. 17 July 2017.

- Steger, Isabella (17 August 2017). "Hong Kong's government finally managed to put democracy fighter Joshua Wong behind bars". Quartz.

- "Lester Shum calls on public to join protest march". Radio Television Hong Kong. 19 August 2017.