Climate change in Canada

In Canada, mitigation of anthropogenic climate change and global warming is a topic of central political concern. According to the 2019 report Canada's Changing Climate Report (CCCR)[1] which was commissioned by Environment and Climate Change Canada, Canada's annual average temperature over land has warmed by 1.7 C since 1948. The rate of warming is even higher in Canada's North, in the Prairies and northern British Columbia.[2]

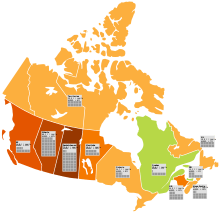

2 eq. per capita

Observed impacts

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC), formerly Environment Canada, is a federal department with the stated role of protecting the environment, conserving national natural heritage, and also providing weather and meteorological information.[3] According to ECCC[4] "warming over the 20th century is indisputable and largely due to human activities" adding "Canada's rate of warming is about twice the global rate: a 2°C increase globally means a 3 to 4ºC increase for Canada".[5] Berkeley Earth has reported that 2015 was "unambiguously" the warmest year on record across the world, with the Earth’s temperature more than 1.0 C (1.8 F) above the 1850-1900 average.[6]

ECCC lists impacts of climate change consistent with global changes. Temperature-related changes include longer growing season, more heatwaves and fewer cold spells, thawing permafrost, earlier river ice break-up, earlier spring runoff, and earlier budding of trees. Meteorological changes include an increase in precipitation and more snowfall in northwest Arctic.[4] Highlighting that "Warming is not uniform ...(the) Arctic is warming even faster", ECCC notes 2012 had the lowest extent of Arctic sea ice on record up to 2014.

ECCC's Climate Research Division summarized annual precipitation changes to support biodiversity assessments by the Canadian Councils of Resource Ministers. Evaluating records up to 2007 they observed: "Precipitation has generally increased over Canada since 1950 with the majority of stations with significant trends showing increases. The increasing trend is most coherent over northern Canada where many stations show significant increases. There is not much evidence of clear regional patterns in stations showing significant changes in seasonal precipitation except for significant decreases which tend to be concentrated in the winter season over southwestern and southeastern Canada. While the previous sentence might be technically correct in part, all seasons show increased precipitation in Canada, especially in the Winter, Spring, and Fall months.[7] Also, increasing precipitation over the Arctic appears to be occurring in all seasons except summer."[8]

ECCC climate specialists have assessed trends in short-duration rainfall patterns using Engineering Climate Datasets: "Short-duration (5 minutes to 24 hours) rainfall extremes are important for a number of purposes, including engineering infrastructure design, because they represent the different meteorological scales of extreme rainfall events." A "general lack of a detectable trend signal", meaning no overall change in extreme,short-duration rainfall patterns was observed in the single station analysis. In relation to design criteria used for traditional water management and urban drainage design practice (e.g., Intensity-Duration-Frequency (IDF) statistics), the evaluation "shows that fewer than 5.6% and 3.4% of the stations have significant increasing and decreasing trends, respectively, in extreme annual maximum single location observation amounts." On a regional basis, southwest and the east (Newfoundland) coastal regions generally showed significant increasing regional trends for 1- and 2-hour extreme rainfall durations. Decreasing regional trends for 5 to 15 minute rainfall amounts were observed in the St. Lawrence region of southern Quebec and in the Atlantic provinces.[9]

Climate change melts ice and increases the mobility of the ice. In May and June 2017 dense ice—up to 8 metres (25ft) thick—was in the waters off the northern coast of Newfoundland, trapping fishing boats and ferries.[10]

The Public Health Agency of Canada reported that incidences of Lyme Disease increased from 144 cases in 2009 to 2017. Dr. Duncan Webster, an infectious disease consultant at Saint John Regional Hospital, links this increase in disease incidence to the increase in the population of blacklegged ticks. The tick population has increased due largely to shorter winters and warmer temperatures associated with climate change.[11]

Emissions

In 2000, Canada ranked ninth out of 186 countries in terms of per capita greenhouse gas emissions without taking into account land use changes. In 2005 it ranked eighth.[12] In 2009, Canada was ranked seventh in total greenhouse gas emissions behind Germany and Japan.[13] In 2018 of all the G20 countries, Canada was second only to Saudi Arabia for per capita emissions.[14]

Canada is a large country with a low population density, so transportation—often in cold weather when fuel efficiency drops—is a big part of the economy. In 2016, 25 per cent of Canada's greenhouse gases (GHG)s came from trucks, trains, airplanes and cars .[15] The largest source of GHG emissions, accounting for 26% of the national total, is from the oil and gas sector, driven by high emissions from tar sands projects.

According to Canada's Energy Outlook, the Natural Resources Canada (NRCan) report,[16] NRCan estimates that Canada's GHG emissions will increase by 139 million tonnes between 2004 and 2020, with more than a third of the total coming from petroleum production and refining. Upstream emissions will decline slightly, primarily from gas field depletion and from increasing production of coalbed methane, which requires less processing than conventional natural gas. Meanwhile, emissions from unconventional resources and refining will soar.[17] However, the estimates for carbon emissions differ amongst Environment Canada, World Resources Institute and the International Energy Agency by nearly 50%. The reasons for the differences have not been determined.

Public policy

Kyoto Protocol

Canada is a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol. However, the Liberal government that later signed the accord took little action towards meeting Canada's greenhouse gas emission targets. Although Canada committed itself to a 6% reduction below the 1990 levels for the 2008–2012 as a signatory to the Kyoto Protocol, the country did not implement a plan to reduce greenhouse gasses emissions. Soon after the 2006 federal election, the new minority government of Conservative Prime Minister Stephen Harper announced that Canada could and would not meet Canada's commitments. The House of Commons passed several opposition-sponsored bills calling for government plans for the implementation of emission reduction measures.

Canadian and North American environmental groups feel that Canada lacks credibility on environmental policy and regularly criticize Canada in international venues. In the last few months of 2009, Canada's attitude was criticized at the Asia-Pacific Economic Co-operation (APEC) conference,[18] at the Commonwealth summit,[19] and the Copenhagen conference.[20]

In 2011, Canada, Japan and Russia stated that they would not take on further Kyoto targets.[21] The Canadian government invoked Canada's legal right to formally withdraw from the Kyoto Protocol on December 12, 2011.[22] Canada was committed to cutting its greenhouse emissions to 6% below 1990 levels by 2012, but in 2009 emissions were 17% higher than in 1990. Environment minister Peter Kent cited Canada's liability to "enormous financial penalties" under the treaty unless it withdrew.[21][23] He also suggested that the recently signed Durban agreement may provide an alternative way forward.[24] Canada's decision was strongly criticized by representatives of other ratifying countries, including France and China.

Harper Government (2006–2015)

Under the tenure of Stephen Harper, who was Prime Minister from 2006 to 2015, the Kyoto Accord was abandoned and the Clean Air Act was unveiled on October 19, 2006.[25]

In 2009, Canada's two largest provinces, Ontario and Quebec, became wary of federal policies shifting the burden of greenhouse reductions on them in order to give Alberta and Saskatchewan more room to further develop their oil sands reserves.[26]

In 2010 Graham Saul, who represented the Climate Action Network Canada (CAN) — a coalition of 60 non-governmental organisations — commented on the 40-page CAN report "Troubling Evidence"[27] which claimed that,[28]

"Canada's climate researchers are being muzzled, their funding slashed, research stations closed, findings ignored and advice on the critical issue of the century unsought by Prime Minister Stephen Harper's government."

— Leahy The Guardian 2010

By 2014 award-winning American/Canadian limnologist, David Schindler, argued that Harper's administration had put "economic development ahead of all other policy objectives", in particular the environment.[29]

"It’s like they don’t want to hear about science anymore. They want politics to reflect economics 100 per cent - economics being only what you can sell, not what you can save."

— David Schindler 2014

Trudeau Government (2015–present)

Election promises

After being elected, prime minister Justin Trudeau outlined the Liberal government's Climate Action Plan:[30]

- “We will fulfil our G20 commitment and phase out subsidies for the fossil fuel industry over the medium-term.”

- “We will also work in partnership with the United States and Mexico to develop an ambitious North American clean energy and environmental agreement.”

- “Together, we will attend the Paris climate conference, and within 90 days formally meet to establish a pan-Canadian framework for combatting climate change.”

- “We will endow the Low Carbon Economy Trust with $2 billion in our mandate.”

While the Liberal government has fulfilled many of its program commitments relating to climate change, environment commissioner Julie Gelfand described the country's lack of progress in reducing emissions as “disturbing" and noted that it was on track to miss its climate change targets.[30]

Cabinet appointments and Paris Summit

Trudeau has appointed Stéphane Dion to the position of Foreign Affairs. Dion is known as being very supportive of climate change policies. Catherine McKenna has been appointed Minister to the newly named Environment and Climate Change. McKenna is known for her legal work surrounding social justice. Trudeau and McKenna garnered the attention of the global media when they attended the Paris climate summit. Canada has committed to the following:[30]

- arrest global temperature increase at 1.5 °C

- phase out fossil fuels

- financial support of clean energy

- assist developing countries to meet their targets

Fossil fuel emissions

Even though fossil fuels will be phased out in "the medium term" Trudeau has stated that the Kinder Morgan Pipeline will be built. The federal government has also approved the Woodfibre LNG Terminal in Vancouver.[30]

Overview of federal climate policies

Canada has established a special liaison with the IPCC dubbed IPCC Focal Point for Canada. [31]

Canada has established the following climate change funding programs:[31]

- The Low Carbon Economy Fund

- Public Transit Infrastructure Fund

- Climate Action Fund

- Green Infrastructure Fund

- Clean Technology Programs

Indigenous peoples

New climate change programs for Indigenous Peoples:[32]

- Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program

- Northern Responsible Energy Approach for Community Heat and Electricity Program

- Climate Change Preparedness in the North Program

- First Nation Adapt Program

- Indigenous Community-Based Climate Monitoring Program

Carbon tax

The Trudeau government has introduced a carbon tax. Details are different for each province. [31] The federal tax is $20 a tonne in 2018 and will increase by $10 a year until it reaches $50 in April 2022. It also places levies on natural gas, pump gas, propane, butane, and aviation fuel.[33]

Ontario Premier Doug Ford, Albertan Premier Jason Kenney (UCP) and Manitoba Premier Brian Pallister (PC) took the federal government to court on April 15, 2019 and the court ruled in favour (3–2) of the constitutionality of the carbon tax. Ford was criticised by the Green Party for spending $30M on the lawsuit instead of using it for environmental concerns. The provinces are appealing the decision to the Supreme Court of Canada.

Climate change adaptation measures

The Canadian government has adopted 4 adaptation-related programs:[31]

- The Pan-Canadian Framework on Clean Growth

- Export clean technologies globally

- Adopt clean, indigenous energy solutions with less regulation

- Improve the access to information on clean technology

- Expert Panel on Climate Change Adaptation and Resilience Results

- Advise federal government

- Federal Adaptation Policy Framework

- Ensure education of the public on climate change

- Ensure that tools to adapt to climate change are available to Canadians

- Ensure that the federal government is resilient to climate change

- Canadian Centre for Climate Services

- Library of climate resources

- Climate information basics

- Climate Services Support Desk

- Display and download climate data

Canada's Changing Climate Report

Environment and Climate Change Canada (ECCC) released a report called Canada's Changing Climate Report (CCCR). It is essentially a summary of the IPCC 5th Assessment Report, customised for Canada. [34] The report states that coastal flooding is expected to increase in many areas due to global sea-level rise and local land subsidence or uplift.

Legislation

- Climate Change Action Plan 2001

Climate emergency

Following on a motion by prime minister Justin Trudeau, on June 12, 2019 the House of Commons has voted to declare a national climate emergency.[35]

Lobbying

The Canadian Wildlife Federation (CWF), one of the largest conservation organisations in the country, takes an active stance in lobbying on mitigation of global warming. According to CWF the organisation recognised the need for action in 1977.[36] It had published Checkerspot, a now discontinued biannual climate change magazine.

Fossil fuel divestment

Fossil fuel divestment is a social movement which urges everyone from individual investors to large institutions to remove their investments (to divest) from publicly listed oil, gas and coal companies, with the intention of combating climate change by reducing the amount of Green-house gases released into the atmosphere, and holding the oil, gas and coal companies responsible for their role in climate change.

Founder of the movement Bill McKibben, a researcher and academic from the University of Victoria, and creator of the webpage 350.org stated: "If it is wrong to wreck the climate, then it is wrong to profit from the wreckage. We believe […] organizations that serve the public good should divest from fossil fuels".

Movement intentions

- 1. Protect the investor from exposure to the financial risks of ‘unburnable carbon’ whereby fossil fuel reserves become uneconomic or are no longer viable to process due to future climate policy or market conditions

- 2. Divesting from these companies can keep a substantial portion of fossil fuels in the ground

- 3. Large institutions can substitute high-carbon investments with low-carbon transition investments

Limits of divestment

Although the impact of divestment is likely to have limited quantitative success in reducing carbon emissions, the movement can gain momentum as a symbolic gesture that has the potential to shift social expectations of investment practices within businesses. Divestment has the potential to be effective if the divested funds are re-invested into the infrastructure of a low-carbon economy. The impact of divestment is believed to be minimal as the continual purchase of oil and gas (and oil and gas derived products such as plastics) will still sustain the oil and gas companies.

Climate change by province

While the federal government was slow to develop a monitoring and credible reduction regime, several provincial governments have established substantial programs to reduce emissions on their respective territories. British Columbia, Manitoba, Ontario and Quebec have joined the Western Climate Initiative,[37] a group of 7 states of the Western United States whose aim is to establish a common framework to establish a carbon credit market. These provinces have also made commitments regarding the reduction and announced concrete steps to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Alberta has an established "Climate Change Action Plan",[38] released in 2008. The Specified Gas Emitters Regulation in Alberta made it the first jurisdiction in North America to have a price on carbon.[38] Reduction programs in other provinces are much less developed.

However, a cost-effectiveness analysis of these programs by the Fraser Institute has questioned their value. In other jurisdictions, carbon markets, renewable energy sources, electric vehicles, and energy efficiency programs have yielded disappointing benefits in comparison to the funds and regulations that have created them.[39]

Public opinion

Canadian opinion on the threat posed by climate change is higher than their United States counterparts, but sits slightly below the median acceptance opinion rates of other nations included in a Pew Research Center survey in 2018.[40] However the majority of Canadians in every electoral riding of every province in Canada believe that Climate change is happening.[41]

Rates of acceptance for ongoing Climate change are highest in British Columbia and Quebec, and lowest in the prairie provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan. In a survey published by the University of Montreal and colleagues, national belief that the earth was warming was at 83%, while 12% of respondents said the earth was not warming. However when asked if this warming is due to human activity, only 60% of respondents said yes.[42] These numbers are consistent with a 2015 survey that showed 85% of Canadians believed the earth was warming, while only 61% felt this warming was due to human activity; Canadian public opinion that human activity is responsible for global warming slightly declined overall between 2007 to 2015.[43] When asked whether their province has already felt the effects of Climate change, 70% of Canadians responded "yes," including a majority of respondents in almost all electoral ridings; the three ridings in Alberta where opinion was lowest each polled at 49% "yes" just below a majority. National support for action to stop Climate change sits at 58%, with similar levels of support for either a "cap and trade" system (58%) or a direct tax on carbon emissions (54%).[42]

Alberta

The Specified Gas Emitters Regulation has placed a price on carbon dioxide emissions in Alberta since 2007[44] and was renewed to 2017 with increased stringency. It requires "large final emitters", defined as facilities emitting more than 100,000tCO2e per year, to comply with an emission intensity reduction which increases over time and caps at 12% in 2015, 15% in 2016 and 20% in 2017. Facilities have several options for compliance. They may actually make reductions, pay into the Climate Change and Emission Management Fund (CCEMF), purchase credits from other large final emitters or purchase credits from non-large final emitters in the form of offset credits.[45] Criticisms against the intensity-based approach to pricing carbon include the fact that there is no hard cap on emissions and actual emissions may always continue to rise despite the fact that carbon has a price. Benefits of an intensity-based system include the fact that during economic recessions, the carbon intensity reduction will remain equally as stringent and challenging, while hard caps tend to become easily met, irrelevant and do not work to reduce emissions. Alberta has also been criticized that its goals are too weak, and that the measures enacted are not likely to achieve the goals. In 2015, the newly elected government committed to revising the climate change strategy.[46][47]

In Alberta there has been a trend of high summer temperatures and low summer precipitation. This has led much of Alberta to face drought conditions.[48] Drought conditions are harming the agriculture sector of this province, mainly the cattle ranching area.[49] When there is a drought there is a shortage of feed for cattle (hay, grain). With the shortage on crops ranchers are forced to purchase the feed at the increased prices while they can. For those who cannot afford to pay top money for feed are forced to sell their herds.[50][51]

During the drought of 2002, Ontario had a good season and produced enough crops to send a vast amount of hay to those hit the hardest in Alberta. However this is not something that can or will be expected every time there is a drought in the prairie provinces.[52] This causes a great deficit in income for many as they are buying heads of cattle for high prices and selling them for very low prices.[53] By looking at historical forecasts, there is a strong indication that there is no true way to estimate or to know the amount of rain to expect for the upcoming growing season. This does not allow for the agricultural sector to plan accordingly.[54]

As of 2008, Alberta's electricity sector was the most carbon-intensive of all Canadian provinces and territories, with total emissions of 55.9 million tonnes of CO

2 equivalent in 2008, accounting for 47% of all Canadian emissions in the electricity and heat generation sector.[55]

In November 2015, Premier Rachel Notley unveiled plans to increase the province's carbon tax to $20 per tonne in 2017, increasing further to $30 per tonne by 2018.[56] This policy shift came about partly because of the rejection of the Keystone XL pipeline, which the premier likened to a "kick in the teeth".[57] The province's new climate policies also include phasing out coal-fired power plants by 2030, and cutting emissions of methane by 45% by 2025.[58]

Alberta witnessed the effects of climate change in a dramatic manner when a "perfect storm" of El Niño and global warming contributed to the 2016 Fort McMurray wildfire, which led to the evacuation of the oil-producing town at the heart of the tar sands industry.[59] The area has witnessed an increased frequency of wildfires, as Canada's wildfire season now starts a month earlier than it used to and the annual area burned is twice what it was in 1970.[60]

As to 2019, climate change has already increased wildfires frequency and power in Canada, especially in Alberta. "We are seeing climate change in action," says University of Alberta wildland fire Prof. Mike Flannigan. "The Fort McMurray fire was 1 1/2 to six times more likely because of climate change. The 2017 record-breaking B.C. fire season was seven to 11 times more likely because of climate change."[61].

British Columbia

The extreme weather events of greatest concern in British Columbia include heavy rain and snow falls, heat waves, and drought. They are linked to flooding and landslides, water shortages, forest fires, reduced air quality, as well as costs related to damage to property and infrastructure, business disruptions, and increased illness and mortality. In recent years, significant extreme events and climate impacts in BC have included:

- the pine beetle epidemic, which resulted in 18 million hectares of dead trees and economic impacts for forest-dependent communities;[62]

- 330,000 hectares of forest lost to forest fire in the 2010 fire season alone,[63] and the loss of 334 homes in the 2003 forest fire season;

- flooding in 2010 leading to the destruction of the Bella Coola highway and evacuation of residents from Kingcome Inlet;[64] and

- heat waves, including the one in the summer of 2009, which are associated with increases in heat stroke and respiratory illness.

BC has announced many ambitious policies to address climate change mitigation, particularly through its Climate Action Plan,[65] released in 2008. It has set legislated greenhouse gas reduction targets of 33% below 2007 levels by 2020 and 80% by 2050.[66] BC’s revenue neutral carbon tax is the first of its kind in North America. It was introduced at $10/tonne of CO2e in 2008 and has risen by $5/tonne annual increases until it reached $30/tonne in 2012, where the rate has remained. It is required in legislation that all revenues from the carbon tax are returned to British Columbians through tax cuts in other areas.[67]

BC’s provincial public sector organizations became the first in North America to be considered carbon neutral in 2010, partly by purchasing carbon offsets.[68][69] The Clean Energy Vehicles Program provides incentives for the purchase of approved clean energy vehicles and for charging infrastructure installation.[70] There has been action across sectors including financing options and incentives for building retrofits, a Forest Carbon Offset Protocol, a Renewable and Low Carbon Fuel Standard, and landfill gas management regulation.

BC’s GHG emissions have been going down, and in 2012 (based on 2010 data) BC declared it was within reach of meeting its interim target of a 6% reduction below 2007 levels by 2012. GHG emissions went down by 4.5% between 2007 and 2010, and consumption of all the main fossil fuels are down in BC as well while GDP and population have both been growing.[71]

In 2018 it was announced that the province "after stalling on sustained climate action for several years, admitted they could not meet their 2020 target", the 33% reduction target had stalled at 6.5%.[72] Provincially BC is the second-largest consumer of natural gas at 2.3 billion cubic feet per day.[73]

Ontario

Ontario is Canada’s most populated province [74] and, in 2010, had the second highest greenhouse gas emissions inventory in the country. In 1990, Ontario’s greenhouse gas emissions were 176 megatonnes (Mt) of CO2 equivalent. According to Canada’s 2012 National Inventory Report [75] Ontario’s emissions were 171 Mt in 2010, an amount that represented 25% of Canada’s total emissions for that year. Over the 20-year period between 1990 and 2010, Ontario’s emissions continued to increase until the mid-2000s. Emissions declined significantly in 2008-2009 due in large part to the economic recession. In 2010, Ontario emitted 12.95 tonnes per person,[76] compared with the Canadian average of 20.3 tonnes per person.[77]

In August 2007, the Ontario government released Go Green: Ontario’s Action Plan on Climate Change. The plan established three targets: a 6% reduction in emissions by 2014, 15% by 2020 and 80% by 2050. The government has committed to report annually on the actions it is taking to reduce emissions and adapt to climate change.[78] With the initiatives currently in place, the government projects it will achieve 90% of the reductions needed to meet its 2014 target, and only 60% of those needed to meet the 2020 target.[79]

The largest emissions reductions to date have come from the phase-out of coal-fired power generation by Ontario Power Generation. In August 2007, the government issued a regulation that required the end of coal burning at Ontario’s four remaining coal-fired power plants by the end of 2014.[80] Since 2003, emissions from these plants have dropped from 36.5 Mt to 4.2 Mt.[81] In January 2013, the government announced that coal will be completely phased out one year early, by the end of 2013.[82] The last coal generating station was closed on April 8, 2014 in Thunder Bay.[83]

Through the Green Energy and Green Economy Act, 2009[84] Ontario implemented a feed-in tariff to promote the development of renewable energy generation. Ontario is also a member of the Western Climate Initiative. In January 2013, a discussion paper was posted on the Environmental Registry seeking input on the development of a greenhouse gas emissions reduction program for industry.

Over the years, transportation emissions have continued to increase. Growing from 44.8 Mt in 1990 to 59.5 Mt in 2010, transportation is responsible for the largest amount of greenhouse gas emissions in the province. Efforts to reduce these emissions include investing in public transit and providing incentives for the purchase of electric vehicles.

The government also recognizes the need for climate change adaptation and, in April 2011, released Climate Ready: Ontario’s Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan 2011–2014.[85]

As required by the Environmental Bill of Rights, 1993, the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario does an independent review and reports annually to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario on the progress of activities in the province to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

On June 7, 2018, the Progressive Conservative Party of Ontario under Doug Ford was elected to a majority government.[86][87] Since then there has been a great deal of controversy regarding the environmental policies of his government. Among the changes to environmental policy by Ford's government were the withdrawal of Ontario from the Western Climate Initiative emissions trading system, which had been implemented by the previous Liberal government, and eliminating the office of the Environmental Commissioner of Ontario, a non-partisan officer of the Legislative Assembly of Ontario charged with enforcing Ontario's Environmental Bill of Rights (EBR).[88] The Ford government released a report indicating that the duties of the Environmental Commissioner would be transferred to the Auditor General of Ontario.[89][90][91]Other criticisms levelled by Mike Schreiner of the Green Party of Ontario include cuts to the Ministry of the Environment, Conservation and Parks as well as making unspecified changes to the Endangered Species Act.[88] Of all of Ford's policies, the abandoning of the Cap and Trade system and mounting a legal challenge to the federal government's carbon tax (which was imposed to replace Cap and Trade) have been the most controversial. Ford is spending $30M to fight the constitutionality of the federally imposed carbon tax, along with the provinces of Manitoba and Saskatchewan. All three provinces involved have Progressive Conservative governments, the traditional nemesis of the Liberals. Ford has been criticised for not putting the money to better use and causing an unnecessary burden on taxpayers. The court ruled in favour of the federal government but the provinces are appealing the decision.[92] Ford has been very vocal about this and maintains that the carbon tax will cause a recession. Economists have studied the issue and do not agree, citing the example of British Columbia, which has had a carbon tax since 2008 causing no economic downturn for the province.[93] A December 2018 Ipsos-Reid poll was conducted to gauge the public's opinion of Ford's environmental policies. The poll results were as follows[94]:

- Negative - 45%

- Positive - 27%

- Neutral - 28%

The federal minister of Environment and Climate Change Canada, Catherine McKenna states that the carbon tax has been shown to be the most economical way of reducing emissions.[93]

Quebec

Greenhouse gas emissions increased by 3.8% in Quebec between 1990 and 2007, to 85.7 megatonnes of CO2 equivalent before falling to 81.7 in 2015. At 9.9 tonnes per capita, Quebec's emissions are well below the Canadian average (20.1 tonnes) and accounted for 11.1% of Canada's total in 2015.[95].

Emissions in the electricity sector spiked in 2007, due to the operation of the TransCanada Energy combined cycle gas turbine in Becancour. The generating station, Quebec's largest source of greenhouse gas emissions that year, released 1,687,314 tonnes of CO2 equivalent in 2007[96] or 72.1% of all emissions from the sector and 2% of total emissions. The plant was closed in 2008[97] in 2009[98] and in 2010.[99]

Between 1990—the reference year of the Kyoto Protocol—and 2006, Quebec's population grew by 9.2% and Quebec's GDP of 41.3%. The emission intensity relative to GDP declined from 28.1% during this period, dropping from 4,500 to 3,300 tonnes of CO2 equivalent per million dollars of gross domestic product (GDP).[100]

In May 2009, Quebec became the first jurisdiction in the Americas to impose an emissions cap after the Quebec National Assembly passed a bill capping emissions from certain sectors. The move was coordinated with a similar policy in the neighboring province of Ontario and reflects the commitment of both provinces as members of the Western Climate Initiative.[101]

On November 23, 2009, the Quebec government pledged to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 20% below the 1990 base year level by 2020, a goal similar to that adopted by the European Union. The government intends to achieve its target by promoting public transit, electric vehicles and intermodal freight transport. The plan also calls for the increased use of wood as a building material, energy recovery from biomass, and a land use planning reform.[102] As of 2015 the rate of emissions has been reduced by 8.8% [103]. In order to encourage electrification of the transportation sector, Quebec has introduced numerous policies to promote the purchase of electric vehicles, with the result that 9.8% of all new car sales in Quebec are electric vehicles.[104]

Impacts on forestry

According to Environment Canada’s 2011 annual report, there is evidence that some regional areas within the western Canadian boreal forest have increased by 2 °C since 1948.[105] The rate of the changing climate is leading to drier conditions in the boreal forest, which leads to a whole host of subsequent issues.[106] This leads to a challenge for the forestry industry to sustainably manage and conserve trees within boreal forest. Climate change will have a direct impact on the productivity of the boreal forest, as well as health and regeneration.[106] As a result of the rapidly changing climate, trees are migrating to higher latitudes and altitudes (northward), but some species may not be migrating fast enough to follow their climatic habitat.[107][108][109] Moreover, trees within the southern limit of their range may begin to show declines in growth.[110] Drier conditions are also leading to a shift from conifers to aspen in more fire and drought-prone areas.[106]

Assisted migration of tree species within the boreal forest is one tool that has been proposed and is currently under study.[111] It involves deliberately moving tree species to locations that may better climatically suit them in the future.[111][112] For species that may not be able to disperse easily, have long generation times or have small populations, this form of adaptative management and human intervention may help them survive in this rapidly changing climate.[111] Assisted migration may offer a potential option to lessen the risks that climate change poses to towards maintaining a sustainable industry, in terms of productivity and health.[113]

There may be benefits and/or consequences to applying assisted migration on wide scale in Canada.[109][111][113] Assisted migration may prevent the extinction of certain tree species, enable and conserve market-based goods such as wood products, and conserve processes and services of an ecosystem.[111] Unfortunately, assisted migration could result in competition between the already established trees with the introduced trees, breeding of the introduced trees with established trees or the disruption of key ecological processes. Any decision made on assisted migration to be implemented in the forestry industry will need continued and rely on informed research and long-term studies.[109][113]

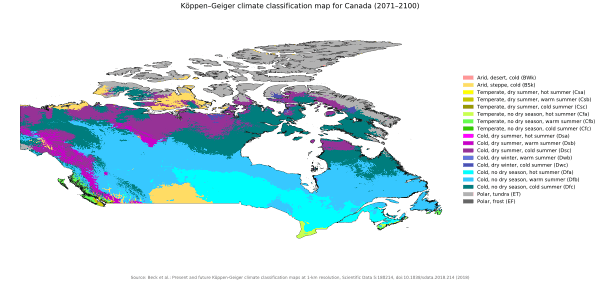

Present and future Köppen-Geiger climate classification maps

Statistics

| in Mt CO2 equivalent | Change 2005-2017 (%) | Share in 2017 (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2005 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | ||||

| Energy (Stationary Combustion Sources) | Public Electricity and Heat Generation | 125 | 91 | 87 | 84 | 87 | 81 | 79 | 11% | |

| Petroleum Refining Industries | 20 | 19 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 18 | 3% | ||

| Oil and Gas Extraction | 63 | 86 | 92 | 97 | 99 | 100 | 106 | 15% | ||

| Mining | 4.3 | 6.0 | 5.4 | 5.0 | 4.6 | 4.3 | 3.9 | 1% | ||

| Manufacturing Industrie | 48 | 44 | 45 | 45 | 44 | 42 | 43 | 6% | ||

| Construction | 1.5 | 1.4 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 1.3 | 0% | ||

| Commercial & Institutional | 33 | 29 | 30 | 31 | 30 | 30 | 31 | 4% | ||

| Residential | 46 | 42 | 44 | 46 | 43 | 39 | 41 | 6% | ||

| Agriculture and forestry | 2.2 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.6 | 3.8 | 3.7 | 1% | ||

| Energy (Transport) | Domestic Aviation | 7.6 | 7.3 | 7.6 | 7.2 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 7.1 | 1% | |

| Road Transportation | 130 | 140 | 144 | 141 | 143 | 145 | 144 | 20% | ||

| Railways | 6.6 | 7.6 | 7.3 | 7.5 | 7.1 | 6.5 | 6.6 | 0% | 1% | |

| Domestic Navigation | 6.4 | 5.6 | 5.2 | 4.8 | 4.7 | 3.6 | 4.4 | 1% | ||

| Other Transportation | 42 | 36 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 39 | 40 | 6% | ||

| Energy (Fugitives Sources) | 61 | 59 | 61 | 63 | 60 | 55 | 56 | 8% | ||

| Total Energy Uses | 595 | 578 | 589 | 594 | 592 | 575 | 583 | 81% | ||

| Industrial processes and product use | 56 | 58 | 55 | 53 | 47 | 55 | 54 | 8% | ||

| Agriculture | Enteric Fermentation | 31 | 25 | 25 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 3% | |

| Manure Management | 8,8 | 7,7 | 7,8 | 7,7 | 7,8 | 7,9 | 8 | 1% | ||

| Agricultural Soils | 19 | 22 | 24 | 23 | 24 | 24 | 25 | 3% | ||

| Liming, Urea Application and Other Carbon-containing Fertilizers | 1,4 | 2,3 | 2,7 | 2,5 | 2,6 | 2,5 | 2,5 | 0% | ||

| Waste | 20 | 18 | 18 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 19 | 3% | ||

| Total Non-Energy Sources | 136 | 133 | 132 | 130 | 124 | 133 | 133 | 19% | ||

| Total GHG | 730 | 711 | 722 | 723 | 722 | 708 | 716 | 100% | ||

| in Mt CO2 equivalent | Change 1990-2017 (%) | Share in 2017 (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2005 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |||

| Oil and Gas | 106 | 158 | 176 | 186 | 193 | 192 | 187 | 195 | 27% | |

| Electricity | 94 | 119 | 84 | 81 | 78 | 81 | 76 | 74 | 10% | |

| Transportation | 122 | 162 | 172 | 175 | 173 | 174 | 174 | 174 | 24% | |

| Heavy Industry | 97 | 87 | 80 | 78 | 78 | 77 | 76 | 73 | 10% | |

| Buildings | 74 | 86 | 86 | 86 | 88 | 86 | 82 | 85 | 12% | |

| Agriculture | 57 | 72 | 70 | 72 | 71 | 71 | 72 | 72 | 10% | |

| Waste & Others | 52 | 47 | 42 | 43 | 42 | 42 | 41 | 42 | 6% | |

| National GHG Total | 602 | 730 | 711 | 722 | 723 | 722 | 708 | 716 | 100.0% | |

| in Mt CO2 equivalent | Change 1990-2017 (%) | Share in 2017 (%) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1990 | 2005 | 2012 | 2013 | 2014 | 2015 | 2016 | 2017 | |||

| 9,4 | 9,9 | 9,4 | 9,4 | 10 | 11 | 11 | 10 | 1,40% | ||

| 1,9 | 2 | 2,1 | 1,7 | 1,7 | 1,7 | 1,8 | 1,8 | 0,25% | ||

| 20 | 23 | 19 | 18 | 16 | 17 | 16 | 16 | 2,24% | ||

| 16 | 20 | 17 | 15 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 14 | 1,96% | ||

| 86 | 86 | 80 | 80 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 78 | 10,92% | ||

| 180 | 204 | 169 | 168 | 166 | 165 | 162 | 159 | 22,27% | ||

| 18 | 20 | 20 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 21 | 22 | 3,08% | ||

| 44 | 68 | 71 | 73 | 76 | 79 | 76 | 78 | 10,92% | ||

| 173 | 231 | 261 | 271 | 276 | 275 | 264 | 273 | 38,24% | ||

| 52 | 63 | 60 | 61 | 60 | 59 | 61 | 62 | 8,68% | ||

| 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,6 | 0,6 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0,5 | 0% | 0,07% | |

| n/a | 1,6 | 1,5 | 1,3 | 1,5 | 1,7 | 1,6 | 1,2 | n/a | 0,17% | |

| n/a | 0,4 | 0,5 | 0,7 | 0,7 | 0,6 | 0,6 | 0,6 | n/a | 0,08% | |

| Canada[note 1] | 602 | 730 | 711 | 722 | 723 | 722 | 708 | 714 | 100% | |

See also

- Arctic Climate Impact Assessment

- Climate change in the Arctic

- Environmental issues in Canada

- Hard Choices: Climate Change in Canada (2004 book)

- List of countries by greenhouse gas emissions per capita

- Renewable energy in Canada

- Regional effects of global warming

- 2012 North American drought

- Summer 2012 North American heat wave

- List of articles about Canadian tar sands

Notes and references

Notes

- Some emissions are only reported at the national level.

References

- Bush, E.; Lemmen, D.S., eds. (2019). Canada's Changing Climate Report (PDF). Government of Canada (Report). Ottawa, Ontario. p. 444. ISBN 978-0-660-30222-5. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- April 1, 2019 (April 1, 2019). "Canada warming at twice the global rate, leaked report finds". CBC News. Retrieved May 22, 2019.

- "About Environment and Climate Change Canada". About Environment and Climate Change Canada. Government of Canada. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Environment and Climate Change. "Environment and Climate Change Canada - Publications - The Science of Climate Change". www.ec.gc.ca. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Environment and Climate Change. "Environment and Climate Change Canada - Climate Change - The Science of Climate Change". ec.gc.ca. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- "Temperature Reports - Berkeley Earth". Berkeley Earth. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Environment (2016-04-28). "Precipitation change in Canada". Retrieved 2018-03-05.

- Canada, Government of Canada, Environment (January 27, 2011). "biodivcanada.ca - Technical Reports". www.biodivcanada.ca. Retrieved January 24, 2016.

- Shephard, Mark W.; Mekis, Eva; Morris, Robert J.; Feng, Yang; Zhang, Xuebin; Kilcup, Karen; Fleetwood, Rick (October 20, 2014). "Trends in Canadian Short‐Duration Extreme Rainfall: Including an Intensity–Duration–Frequency Perspective". Atmosphere-Ocean. 52 (5): 398–417. doi:10.1080/07055900.2014.969677. ISSN 0705-5900.

- change study in Canada's Hudson Bay thwarted by climate change Guardian June 14, 2017

- "Woman gets Lyme disease diagnosis after 13-year battle, as number of cases rises". February 12, 2020. Retrieved February 21, 2020.

- "WRI Climate Analysis Indicators Tool (registration required to access data)".

- Rogers, Simon; Evans, Lisa (January 31, 2011). "World carbon dioxide emissions data by country: China speeds ahead of the rest". The Guardian. London. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- https://www.climate-transparency.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/11/Brown-to-Green-Report-2018_rev.pdf

- https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/environmental-indicators/greenhouse-gas-emissions.html |date=November 25, 2018

- Canada's Energy Outlook: The Reference Case 2006 Archived June 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- Beyond Bali

- Cheadle, Bruce (November 14, 2009). "Harper Criticized On Climate Change At APEC Summit". Canadian Press. Toronto: CITY-TV. Archived from the original on June 4, 2011. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- Carrington, Damian (November 26, 2009). "Scientists target Canada over climate change". The Guardian. London. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- Cryderman, Kelly (December 6, 2009). "Canada has target on its back headed into Copenhagen summit". Canwest News Service. Global TV. Retrieved December 18, 2009.

- "Canada pulls out of Kyoto protocol". The Guardian. London. December 13, 2011. Retrieved December 13, 2011.

- "Canada withdrawing from Kyoto". The Toronto Star. December 12, 2011. Retrieved December 12, 2011.

- David Ljunggren; Randall Palmer (December 13, 2011), "Canada to pull out of Kyoto protocol", Reuters, Financial Post, retrieved January 9, 2012

- "Canada under fire over Kyoto protocol exit". BBC News. December 13, 2011.

- McMillan Binch Mendelsohn (May 2007). "Made-in-Canada Clean Air Act – Stepping back from Kyoto?" (PDF). Emissions Trading and Climate Change Bulletin. Archived from the original (PDF) on January 29, 2016. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- Woods, Allan (December 15, 2009). "Ontario and Quebec fear chill over climate pact". Toronto Star. Toronto. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- Cuddy, Andrew (March 2010). "Troubling Evidence: The Harper Government's Approach to Climate Science Research in Canada" (PDF). Climate Action Network Canada (CAN). p. 38. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- Leahy, Stephen (March 18, 2010). "Canadian government 'hiding truth about climate change', report claims". London: Guardian. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- "Research Cutbacks By Government Alarm Scientists". CBC via Huffington Post. October 1, 2014. Retrieved October 28, 2015.

- Prime Minister Justin Trudeau on Climate Change, ,The Narwahl,Unknown author, Retrieved May 20, 2019

- Canada's action on climate change,Government of Canada, Retrieved May 20, 2019

- Indigenous and Northern Affairs,,AANDC, Retrieved May 20, 2019

- Pricing Pollution. How it will work.,ECCC Website, Retrieved May 20, 2019

- Canada's Changing Climate Report,Natural Resources Canada, Retrieved May 20, 2019

- Vote No. 1366, House of Commons of Canada, Retrieved July 4, 2019

- Climate Change Policy, archived from the original on July 21, 2010

- Government of Canada (2015). "Canada's Action on Climate Change" (PDF). Retrieved September 14, 2015.

- Government of Alberta (2008). "Climate Change Action Plan" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on January 27, 2016. Retrieved September 8, 2015.

- Green, Kenneth (November 16, 2017). "Canada's Climate Action Plans: Are They Cost-effective?" (PDF). Fraser Institute. Retrieved November 23, 2017.

Canadian governments have aggressively, and with little up-front analysis, rolled out climate action plans that are going to cost a great deal of money, but, most likely, will yield very little return in terms of environmental benefits.

- Fagan, Moira; Huang, Christine. "A look at how people around the world view climate change". Pew Research Center. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- "Canadians in every riding support climate change action". Macleans. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- "Changements climatique". Université de Montreal. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- "Canadian public opinion about climate change" (PDF). David Suzuki Foundation. Retrieved December 22, 2019.

- "Climate Change and Emissions Management Act: Specified Gas Emitters Regulation", Alberta Queen’s Printer, Edmonton, Alberta, p. 27, 2007, retrieved October 28, 2015

- "Specified Gas Emitters Regulation", Alberta Environment and Parks (AEP), 2007, retrieved October 28, 2015

- "Climate Leadership", Government of Alberta, 2015, archived from the original on October 14, 2015, retrieved October 28, 2015

- "Climate Leadership Discussion Document" (PDF), Government of Alberta, p. 57, August 2015, archived from the original (PDF) on November 20, 2015, retrieved October 28, 2015

- "Alberta Environment: Alberta River Basins Precipitation Maps". Environment.alberta.ca. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- "Agriculture Drought Risk Management Plan for Alberta - Strategic Plan". .agric.gov.ab.ca. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- "Alberta ranchers forced to sell herds". CBC. August 18, 2009. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- "Drought forcing Alberta ranchers to sell off cattle". Cbc.ca. July 9, 2002. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- "CBC News - Canada - Ontario hay arrives in drought-stricken Alberta". Cbc.ca. August 7, 2002. Archived from the original on July 30, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- "CBC News - Edmonton - Alberta county declares 'state of agricultural disaster' over drought". Cbc.ca. June 17, 2009. Archived from the original on June 26, 2009. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- "The Atlas of Canada - Precipitation". Atlas.nrcan.gc.ca. July 27, 2004. Archived from the original on October 2, 2012. Retrieved November 21, 2009.

- Environment Canada (April 15, 2010). National Inventory Report Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada 1990–2008 (3 volumes). UNFCCC.

- Bakx, Kyle (April 24, 2016). "Alberta's carbon tax: What we still don't know". CBC News. Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- Giovanetti, Justin; Jones, Jeffrey (November 22, 2015). "Alberta carbon plan a major pivot in environmental policy". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- "Climate Leadership". Alberta Government. Archived from the original on May 7, 2016. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- McGrath, Matt (May 5, 2016). "'Perfect storm' of El Niño and warming boosted Alberta fires". BBC News. BBC. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- Kahn, Brian (May 4, 2016). "Here's the Climate Context For the Fort McMurray Wildfire". Climate Central. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- Derworiz, Colette (June 9, 2019). "'Can't be any more clear': Scientist says fires in Alberta linked to climate change". CTV News. Retrieved June 12, 2019.

- "Mountain Pine Beetle". Ministry of Forestry. Archived from the original on April 5, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- "Summary of Previous Fire Seasons". Wildfire Management Branch. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- "Flooding Cuts Off B.C. Communities". CBC News. September 26, 2010. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- "Climate Action Plan". Climate Action Secretariat. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- "Greenhouse Gas Reduction Targets Act". BC Laws. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- "Carbon Tax". Ministry of Finance. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- "Carbon Neutral BC Public Sector". Province of BC. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- https://www2.gov.bc.ca/gov/content/environment/climate-change/public-sector/cnar?keyword=carbon&keyword=neutral

- "Clean Energy Vehicle Incentives". Province of BC. Archived from the original on November 14, 2011. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- "Making Progress on B.C.'s Climate Action Plan" (PDF). Province of BC. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 12, 2013. Retrieved April 4, 2013.

- https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/b-c-government-drops-greenhouse-gas-target-for-new-2030-goal-1.4653075

- https://www.neb-one.gc.ca/nrg/ntgrtd/mrkt/nrgsstmprfls/cda-eng.html

- Statistics Canada. Table 051-0005 - Estimates of population, Canada, provinces and territories, quarterly (persons), CANSIM (database).

- National Inventory Report 1990-2010: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada

- Climate Vision: Climate Change Progress Report. Technical Appendix

- National Inventory Report 1990-2010: Greenhouse Gas Sources and Sinks in Canada, Part I.

- "Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change". Ministry of the Environment and Climate Change. Retrieved August 2, 2016.

- Climate Vision: Climate Change Progress Report. Technical Appendix.

- Ontario Regulation 496/07 – Cessation of Coal Use – Atikokan, Lambton, Nanticoke and Thunder Bay Generating Stations, issued under the Environmental Protection Act.

- Ontario Power Generation , 2011 Annual Report Archived March 9, 2013, at the Wayback Machine

- Cleaner Air and More Green Space for Ontarians to Enjoy: McGuinty Government Closing Coal Plants Earlier, Growing Greenbelt. January 20, 2013

- "Ontario Power Generation Moves to Cleaner Energy Future: Thunder Bay Station Burns Last Piece of Coal" (PDF). Ontario Power Generation. Retrieved January 7, 2020.

- An Act to enact the Green Energy Act, 2009 and to build a green economy, to repeal the Energy Conservation Leadership Act, 2006 and the Energy Efficiency Act and to amend other statutes.

- Climate Ready: Ontario’s Adaptation Strategy and Action Plan 2011 – 2014

- Doug Ford's Progressive Conservatives win majority in Ontario, CTV News, Graham Slaughter, Retrieved May 22, 2019

- Doug Ford has won Ontario’s election. What happens now? A guide, The Globe and Mail, Nathan Denette, Retrieved May 22, 2019

- Doug Ford government one of the most 'anti-environmental' in generations, says Green Party leader CBC News, Lisa Xing, Retrieved May 22, 2019

- Ontario environment watchdogs say Doug Ford just gutted a law that protects your rights,National Observer, Fatima Syed, Retrieved May 22, 2019

- Doug Ford's Climate Policy Is 'Very Frightening,' Watchdog SaysHuffington Post, Canadian Press, Retrieved May 22, 2019

- FAQs — Integrating the Work of the Environmental Commissioner into the Auditor General’s Office,Government of Ontario PDF, Retrieved May 22, 2019

- LILLEY: Carbon tax ruling splits court, appeal to come,Toronto Sun, Brian Lilley, Retrieved May 21, 2019

- Doug Ford warns of recession with carbon tax, economists disagree,The Globe and Mail, Laura Stone, Retrieved May 22, 2019

- Internal poll finds voters have negative opinion of PCs environmental policies,CBC News, Allison Jones, Retrieved May 22, 2019

- http://www.budget.finances.gouv.qc.ca/budget/2018-2019/en/documents/ClimateChange_1819.pdf |date =Nov25 2018

- Environnement Canada. "Search Facility Data - Results". Monitoring, Accounting and Reporting on Greenhouse Gases. Archived from the original on June 27, 2013. Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- Baril, Hélène (December 4, 2007). "Ratés dans la stratégie énergétique du Québec". La Presse (in French). Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- Couture, Pierre (July 25, 2008). "Bécancour : Hydro-Québec devra verser près de 200 M$". Le Soleil (in French). Archived from the original on January 15, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2009.

- Couture, Pierre (July 10, 2009). "Hydro-Québec versera 250 millions $ à TransCanada Energy". Le Soleil (in French). Retrieved December 19, 2009.

- Government of Quebec (November 2008). "Inventaire québécois des émissions de gaz à effet de serre en 2006 et évolution depuis 1990" (PDF) (in French). Ministère du Développement durable, de l'Environnement et des Parcs. p. 5. Archived from the original (PDF) on June 16, 2011. Retrieved May 15, 2009.

- Francoeur, Louis-Gilles (May 12, 2009). "Le Québec et l'Ontario tiendront un registre conjoint des émissions de GES". Le Devoir (in French). Montreal. p. 1. Retrieved May 12, 2009.

- Francoeur, Louis-Gilles (November 24, 2009). "Climat: le Québec vise haut". Le Devoir (in French). Montreal. p. 1. Retrieved November 26, 2009..

- http://www.budget.finances.gouv.qc.ca/budget/2018-2019/en/documents/ClimateChange_1819.pdf | date November 25, 2018

- https://www.fleetcarma.com/electric-vehicles-sales-update-q3-2018-canada/ | date=November 25, 2018

- "Annual Regional Temperature Departures". Environment Canada. Archived from the original on January 18, 2012. Retrieved April 2, 2012.

- Hogg, E.H.; P.Y. Bernier (2005). "Climate change impacts on drought-prone forests in western Canada". Forestry Chronicle. 81 (5): 675–682. doi:10.5558/tfc81675-5.

- Jump, A.S.; J. Peñuelas (2005). "Running to stand still: Adaptation and the response of plants to rapid climate change". Ecology Letters. 8 (9): 1010–1020. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2005.00796.x.

- Aiken, S.N.; S. Yeaman; J.A. Holliday; W. TongLi; S. Curtis- McLane (2008). "Adaptation, migration or extirpation: Climate change outcomes for tree populations". Evolutionary Applications. 1 (1): 95–111. doi:10.1111/j.1752-4571.2007.00013.x. PMC 3352395. PMID 25567494.

- McLane, S.C.; S.N. Aiken (2012). "Whiteback pine (Pinus albicaulis) assisted migration potential: testing establishment north of the species range". Ecological Applications. 22 (1): 142–153. doi:10.1890/11-0329.1.

- Reich, P.B.; J. Oleksyn (2008). "Climate warming will reduce growth and survival of Scots pine except in the far north". Ecology Letters. 11 (6): 588–597. doi:10.1111/j.1461-0248.2008.01172.x. PMID 18363717.

- Aubin, I.; C.M. Garbe; S. Colombo; C.R. Drever; D.W. McKenney; C. Messier; J. Pedlar; M.A. Saner; L. Vernier; A.M. Wellstead; R. Winder; E. Witten; E. Ste-Marie (2011). "Why we disagree about assisted migration: Ethical implications of a key debate regarding the future of Canada's forests". Forestry Chronicle. 87 (6): 755–765. doi:10.5558/tfc2011-092.

- Vitt, P.; K. Havens; A.T. Kramer; D. Sollenberger; E. Yates (2010). "Assisted migration of plants: Changes in latitudes, changes in attitudes". Biological Conservation. 143 (1): 18–27. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2009.08.015.

- Ste-Marie, C.; E.A. Nelson; A. Dabros; M.E. Bonneau (2011). "Assisted migration: Introduction to a multifaceted concept". Forestry Chronicle. 87 (6): 724–730. doi:10.5558/tfc2011-089.

- Canada, Environment and Climate Change (August 19, 2019). "Greenhouse gas sources and sinks: executive summary 2019". aem. Retrieved April 6, 2020.

External links

- Canada's Action on Climate Change - Government of Canada

- Environment And Climate Change Canada - Climate Change page

- Canadian Wildlife Federation - Climate change page

- map showing average changes in ice thickness in centimeters per year from 2003 to 2010 with 4 cm ice mass loss shown within Nunavut