Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari

The Autodromo Internazionale Enzo e Dino Ferrari is a race track near the Italian town of Imola, 40 kilometres (24.9 mi) east of Bologna. It is one of the few major international circuits to run in an anti-clockwise direction. The circuit is named after Ferrari's late founder, Enzo Ferrari, and his son, Alfredo Ferrari, who died in 1956 at age 24. The circuit has a FIA Grade One license.[1]

| |

| Location | Imola, Emilia-Romagna, Italy |

|---|---|

| Time zone | UTC+01:00 |

| Coordinates | 44°20′28″N 11°42′48″E |

| FIA Grade | 1 |

| Major events |

|

| Length | 4.909 km (3.050 mi) |

| Turns | 21 |

| Previous layout (1995–2006) | |

| Length | 4.959 km (3.081 mi) |

| Turns | 22 |

| Race lap record |

|

| Original layout with Acque Minerali chicane (1981–1994) | |

| Length | 5.040 km (3.132 mi) |

| Turns | 22 |

| Race lap record |

|

| Original layout (1980) | |

| Length | 5.000 km (3.107 mi) |

| Turns | 20 |

| Race lap record |

|

| Website | autodromoimola.it |

It was the venue for the San Marino Grand Prix. For many years, two Grands Prix were held in Italy every year, so the race held at Imola was named after the nearby state. It also hosted the 1980 Italian Grand Prix, the Italian Grand Prix usually takes place at the Autodromo Nazionale Monza. When Formula One visits Imola, it is seen as the home circuit of Scuderia Ferrari, and masses of supporters come out to support the local team.

History

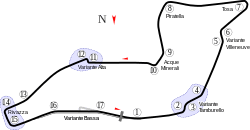

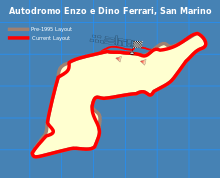

The track was inaugurated as a semi-permanent venue in 1953. It had no chicanes, so the runs from Acque Minerali to Rivazza, and from Rivazza all the way to Tosa, through the pits and the Tamburello, were just straights with a few small bends; the circuit remained in this configuration until 1972.

In April 1953, the first motorcycle races took place, while the first car race took place in June 1954. In April 1963, the circuit hosted its first Formula One race, as a non-championship event, won by Jim Clark for Lotus. A further non-championship event took place at Imola in 1979, which was won by Niki Lauda for Brabham-Alfa Romeo. In 1980 Imola officially debuted in the Formula One calendar by hosting the 1980 Italian Grand Prix. It was the first time since the 1948 Edition held at Parco del Valentino that the Autodromo Nazionale Monza did not host the Italian Grand Prix. The race was won by Nelson Piquet and it was such a success that a new race, the San Marino Grand Prix, was established especially for Imola in 1981. The race was held over 60 laps of the 5 kilometre circuit for a total race distance of 300 kilometres.

Imola has hosted a round of the Superbike World Championship from 2001 to 2006 and later since 2009. It hosts the final round of the FIM Motocross World Championship since 2018.

The World Touring Car Championship visited Imola in 2005 (Race of San Marino), 2008 (Race of Europe), and 2009 (Race of Italy). The venue hosted a round of the International GT Open from 2009 to 2011. The TCR International Series raced at Imola in 2016.

The 6 Hours of Imola was revived in 2011 and added to the Le Mans Series and Intercontinental Le Mans Cup as a season event until 2016. Since 2017 it hosts the 12 Hours of Imola, a round of the 24H Series.

The track was also used as part of the finishing circuit for the 1968 UCI Road World Championships, which saw Italian cyclist Vittorio Adorni winning with a lead of 10 minutes and 10 seconds over runner up Herman Van Springel, the second largest winning margin in the history of the championships, after Georges Ronsse's victory in 1928. In addition Adorni's countryman Michele Dancelli took the bronze and five of the top six finishers were Italian.[2] The circuit was also used for stage 11 of the 2015 Giro d'Italia, which was won by Ilnur Zakarin,[3] and stage 12 of the 2018 Giro d'Italia, won by Sam Bennett.[4]

The Tamburello corner

Despite the addition of the chicanes, the circuit was subject to constant safety concerns, mostly regarding the flat-out Tamburello corner, which was very bumpy and had dangerously little room between the track and a concrete wall which protects the Santerno river that runs behind it. In 1987, Nelson Piquet had an accident there during practice and missed the race due to injury. In the 1989 San Marino Grand Prix, Gerhard Berger crashed his Ferrari at Tamburello after a front wing failure. The car caught fire after the heavy impact but thanks to the quick work of the firefighters and medical personnel Berger survived and missed only one race (the 1989 Monaco Grand Prix) due to burns to his hands. Michele Alboreto also had a fiery accident at the Tamburello corner testing his Footwork Arrows at the circuit in 1991 but escaped injury. Riccardo Patrese also had an accident at the Tamburello corner in 1992 while testing for the Williams team. The death of Ayrton Senna on 1 May 1994 sealed the fate of the corner being run flat out ever again.

1994 San Marino Grand Prix

In the 1994 San Marino Grand Prix, during Friday practice Rubens Barrichello was launched over a kerb and into the top of a tyre barrier at the Variante Bassa, knocking the Brazilian unconscious, though quick medical intervention saved his life. During Saturday qualifying Austrian Roland Ratzenberger crashed head-on into a wall at over 310 km/h at the Villeneuve corner after his Simtek lost the front wing, dying instantly from a basilar skull fracture. The tragedy continued the next day, when the three-time World Champion Ayrton Senna lost control of his car and crashed into the concrete wall at the Tamburello corner on Lap 7. He succumbed shortly after impact as a piece of the car had pierced his helmet and skull. In two unrelated incidents, several spectators and mechanics were also injured during the event.

In the aftermath, the circuit continued to host Grands Prix, but revisions were immediately made in an attempt to make it safer. The flat-out Tamburello corner was reduced to a 4th gear left-right sweeper, and a gravel trap was added to the limited space on the outside of the corner. Villeneuve corner, previously an innocuous 6th gear right-hander into Tosa, was made a complementary 4th gear sweeper, also with a gravel trap on the outside of the corner. In an attempt to retain some of the quickness and character of the old circuit, the arduous chicane at Acqua Minerali was eliminated, and the Variante Bassa was straightened into a single chicane. Many say that the new circuit configuration is not as good as it used to be as a result of the new chicanes at Tamburello and Villeneuve.[5][6]

Another modification made to the Imola track is that of Variante Alta, which is situated at the top of the hill leading down to Rivazza and has the hardest braking point on the lap. The Variante Alta, formerly a high-kerbed chicane, was hit quite hard by the drivers which caused damage to the cars and occasionally was the site of quite a few accidents. Before the 2006 Grand Prix, the kerbs were lowered considerably and the turn itself was tightened to reduce speeds and hopefully reduce the number of accidents at the chicane.

The Grand Prix was removed from the calendar of the 2007 Formula One season.[7] SAGIS, the company that owns the circuit, hoped that the race would be reinstated at the October 2006 meeting of the FIA World Motor Sport Council and scheduled for the weekend of 29 April 2007, provided renovations to the circuit were completed in time for the race, but the reinstatement was denied.[8]

Recent developments

Since 2007, the circuit has undergone major revisions. A bypass to the Variante Bassa chicane was added for cars, making the run from Rivazza 2 to the first Tamburello chicane totally flat-out, much like the circuit in its original fast-flowing days. However the chicane is still used for motorcycle races.

The old pit garages and paddock have been demolished and completely rebuilt while the pitlane was extended and resurfaced. The reconstruction was overseen by German F1 track architect Hermann Tilke.

In June 2008, with most of the reconstruction work completed, The FIA gave the track a "1T" rating, meaning that an official Formula One Test can be held at the circuit; circuits require the "1" homologation to host a Formula One Grand Prix.[9] As of August 2011, the track received a '1' FIA homologation rating after an inspection by Charlie Whiting.[10]

In June 2015, the owners of the circuit confirmed they were in talks to return to the Formula One calendar should Monza, whose contract was scheduled to run out after the 2016 season, be unable to make a new deal to keep hosting a round of the world championship.[11] On 18 July 2016, Imola signed a deal to host the Italian Grand Prix from the 2017 season.[12] However, on 2 September 2016, it was announced that Monza secured a new deal to continue in hosting the race,[13] and Imola's officials took legal action against this decision citing that its contract has been breached.[14] On 8 November 2016, they withdrew their case.[15] In February 2020, the owners at Imola submitted a bid to replace the 2020 Chinese Grand Prix pending its cancellation as a precaution in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.[16]

Non-motorsport events

Since 1981[17], the circuit has been hosting the early-September Mostra Scambio ("Trading Exposition"), an open-air market primarily focused on the exhibition and trade of vintage vehicles and their parts; this event is also popularly (but inaccurately) called CRAME, after the name of the historical society organizing it[18]. The 2020 edition has been canceled due to the COVID-19 [17].

Among the major musical performances held on the track can be listed:

- Heineken Jammin' Festival (1998-2006)

- Sonisphere (2011)

- AC/DC - Rock or Bust World Tour (2015)

- Laura Pausini - Pausini Stadi (2016)

- Guns N' Roses - Not in this Lifetime Tour (2017)

- Mario Biondi (2019)

Partially due to the vicinity of the Romeo Galli athletics stadium, the Acque Minerali park, and the Tre Monti hills, the Autodromo is not commonly used for bicycle or on-foot sporting activities (albeit with notable exceptions, such as two segments of the Giro d'Italia in the 2010s); however, the civic administration does occasionally allocate summer days in which the public can walk or cycle along the track[19].

References

- "List of FIA licensed circuits" (PDF). FIA. 6 February 2015. Retrieved 28 May 2015.

- Fotheringham, Alasdair (19 May 2015). "Giro d'Italia stage 11 preview: Organizers bring back 1968 Worlds finish circuit in Imola". cyclingnews.com. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- O'Shea, Sadhbh (20 May 2015). "Giro d'Italia stage 11: Zakarin motors to win on F1 track in Imola". cyclingnews.com. Retrieved 20 May 2015.

- Arthurs-Brennan, Michelle (17 May 2018). "Sam Bennett breaks into early charge to win stage 12 of the Giro d'Italia". Cycling Weekly. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- BBC (17 February 2006). "Circuit Guide - Imola". BBC News. Retrieved 1 January 2010.

- The Guardian (3 March 2003). "Imola, San Marino". London. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- "San Marino loses Grand Prix race". news.bbc.co.uk. 29 August 2006. Retrieved 27 March 2008.

- "Imola hopes to get back on 2007 calendar". f1.gpupdate.net. 30 August 2006. Retrieved 30 January 2011.

- "Imola receives '1T' FIA rating". en.f1-live.com. 30 August 2006. Archived from the original on 21 July 2008. Retrieved 2 September 2008.

- "F1: Imola Eyes Return With Top FIA Rating". 5 September 2011. Archived from the original on 19 March 2012. Retrieved 5 September 2011.

- "Exclusive: Imola begins talks to save Italian Grand Prix". Motorsport.com. 15 June 2015. Retrieved 11 July 2015.

- Cooper, Adam (18 July 2016). "Imola signs agreement with Ecclestone for Italian GP". Motorsport.com. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- Parkes, Ian (2 September 2016). "Monza secures new three-year F1 deal to host Italian Grand Prix". Autosport.com. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- Rencken, Dieter; Barretto, Lawrence (6 September 2016). "Imola taking legal action over Monza's new Italian GP deal". Autosport.com. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- Rencken, Dieter; Barretto, Lawrence (8 November 2016). "Imola withdraws legal action over Monza's F1 Italian GP". Autosport.com. Retrieved 9 November 2016.

- "2020 F1 Chinese Grand Prix postponed due to novel coronavirus outbreak". formula1.com. 12 February 2020. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- "L'Autodromo di Imola - Storia dell'Autodromo". Mostra Scambio Imola (in Italian). Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Club Romagnolo Auto e Moto d'Epoca" (in Italian). Retrieved 26 June 2020.

- "Attività – Visitare Imola" (in Italian). IAT - Informazione e Accoglienza Turistica, Comune di Imola. Retrieved 26 June 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Autodromo Enzo e Dino Ferrari. |