Caracas

Caracas (/kəˈrækəs, -ˈrɑːk-/, Spanish: [kaˈɾakas]), officially Santiago de León de Caracas, abbreviated as CCS, is the capital and largest city of Venezuela, and the center of the Metropolitan Region of Caracas (or Greater Caracas).[3] Caracas is located along the Guaire River in the northern part of the country, within the Caracas Valley of the Venezuelan coastal mountain range (Cordillera de la Costa). The valley is close to the Caribbean Sea, separated from the coast by a steep 2,200-metre-high (7,200 ft) mountain range, Cerro El Ávila; to the south there are more hills and mountains. The Metropolitan Region of Caracas has an estimated population of almost 3 million inhabitants.

Caracas | |

|---|---|

| Santiago de León de Caracas | |

Caracas as seen from Ávila; Sunset at Plaza Venezuela | |

Flag  Coat of arms | |

| Nicknames: La Sucursal del Cielo La Odalisca del Ávila La Ciudad de la Eterna Primavera | |

| Motto(s): Muy Noble y Leal Ciudad | |

.jpg) Caracas Location in Venezuela and South America  Caracas Caracas (South America) | |

| Coordinates: 10°28′50″N 66°54′13″W | |

| Country | Venezuela |

| State | Capital District |

| Founded | 25 July 1567 |

| Founded by | Diego de Losada |

| Government | |

| • Type | Mayor–council |

| • Body | Government of the Capital District |

| • Chief of Government | Darío Vivas |

| Area | |

| • Capital City | 433 km2 (167 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 4,715.1 km2 (1,820.5 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 900 m (3,000 ft) |

| Highest elevation | 1,400 m (4,600 ft) |

| Lowest elevation | 870 m (2,850 ft) |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Capital City | 2,245,744 |

| Demonyms | Caraquenian (Spanish: caraqueño (m), caraqueña (f)) |

| Time zone | UTC-04:00 (VET) |

| Postal codes[2] | 1000–1090, 1209 |

| Area code | 212 |

| ISO 3166 code | VE-A |

| Website | http://www.caracas.gob.ve/ |

| The area and population figures are the sum of the figures of the five municipalities (listed above) that make up the Distrito Metropolitano. | |

The center of the city is still Catedral, located near Bolívar Square,[4] though some consider the center to be Plaza Venezuela, located in the Los Caobos area.[3][5][6] Businesses in the city include service companies, banks, and malls. Caracas has a largely service-based economy, apart from some industrial activity in its metropolitan area.[7] The Caracas Stock Exchange and Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) are headquartered in Caracas. PDVSA is the largest company in Venezuela. Caracas is also Venezuela's cultural capital, with many restaurants, theaters, museums, and shopping centers. Caracas has some of the tallest skyscrapers in Latin America,[8] such as the Parque Central Towers.[9] The Museum of Contemporary Art of Caracas is one of the most important in South America.[10]

Caracas has one of the highest per capita murder rates in the world, with 111.19 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants.[11]

History

Before the city was founded in 1567,[12] the valley of Caracas was populated by indigenous peoples. Francisco Fajardo, the son of a Spanish captain and a Guaiqueri cacica, who came from Margarita, began establishing settlements in the area of La Guaira and the Caracas valley between 1555 and 1560. Fajardo attempted to establish a plantation in the valley in 1562 after these unsuccessful coastal towns, but it did not last long: it was destroyed by natives of the region led by Terepaima and Guaicaipuro.[13][14] Fajardo's 1560 settlement was known as Hato de San Francisco, and another attempt in 1561 by Juan Rodríguez de Suárez was called Villa de San Francisco, and was also destroyed by the same native people.[1] The eventual settlers of Caracas came from Coro, the German capital of their Klein-Venedig colony around the present-day coastal Colombia–Venezuela border; from the 1540s, the colony had been de facto controlled by Spaniards. Moving eastward from Coro, groups of Spanish settlers founded inland towns including Barquisimeto and Valencia before reaching the Caracas valley.[13]

On 25 July 1567, Captain Diego de Losada laid the foundations of the city of Santiago de León de Caracas.[12] De Losada had been commissioned to capture the valley, and was successful by splitting the natives into different groups to work with, then fighting and defeating each of them.[1] The town was the closest to the coast of these new settlements, and the colonists retained a native workforce, which allowed a trade network to develop between Caracas, the interior, and Margarita; the towns further inland produced ample cotton products and beeswax, and Margarita was a rich source of pearls. The Caracas valley had a good environment for both agricultural and arable farming, which contributed to the system of commerce but meant that the town's population was initially sparse, as it was only large enough to support a few farms.[13]

In 1577, Caracas became the capital of the Spanish Empire's Venezuela Province[15] under the province's new governor, Juan de Pimentel (1576–1583).[1] In the 1580s, Caraqueños started selling food to the Spanish soldiers in Cartagena, who often docked in the coastal city when collecting products from the empire in South America. Wheat was growing increasingly expensive in the Iberian Peninsula, and the Spanish profited from buying it from Caracas farmers. This cemented the city in the empire's trade circuit.[13]

During the 16th and 17th centuries, the coast of Venezuela was frequently raided by pirates. With the coastal mountains of the Central Range as a barrier, Caracas was relatively immune to such attacks, compared to other Caribbean coastal settlements,[13] but in 1595 the Preston–Somers expedition landed and around 200 English privateers, including George Somers and Amyas Preston, crossed the mountains through a little-used pass while the town's defenders were guarding the more frequently used one. Encountering little resistance, the invaders sacked and set fire to the town after a failed ransom negotiation.[16][17] The city managed to rebuild, using wheat profits and "a lot of sacrifice".[1] In the 1620s, farmers in Caracas discovered that cacao beans could be sold, first selling them to native people of Mexico and quickly growing across the Caribbean. The city became important in the Viceroyalty of New Spain, as well as moving from largely native slave labor to African slaves, the first of the Spanish colonies to become part of the slave trade. The city was successful and operated on cacao and slave trade until the 1650s, when an alhorra blight, the Mexican Inquisition of many of their Portuguese traders, and increased cacao production in Guayaquil greatly affected the market. This and the destructive 1641 earthquake put the city into decline, and they likely began illegally trading with the Dutch Empire, which Caraqueños later proved sympathetic to; by the 1670s, Caracas had a trading route through Curaçao.[13]

In 1728, the Guipuzcoan Company of Caracas was founded by the king, and the cacao business grew in importance. Caracas was made one of the three provinces of Nueva Granada, corresponding to Venezuela, in 1739. Over the next three decades the Viceroyalty was variously split, with Caracas province becoming the Venezuela province and then the Captaincy General of Venezuela in 1777, with Caracas as the capital.[1] Venezuela then attempted to become independent, first with the 1797 Gual and España conspiracy, based in Caracas,[18] and then the successful 1811 Venezuelan Declaration of Independence.[1] Caracas then came under worse luck: in 1812, an earthquake destroyed Caracas, a quarter of its population migrated in 1814, and the Venezuelan War of Independence continued until 24 June 1821, when Simón Bolívar defeated royalists in the Battle of Carabobo.[1][19] Urban reforms only took place towards the end of the 19th century, under Antonio Guzmán Blanco: some landmarks were built, but the city remained distinctly colonial until the 1930s.[1]

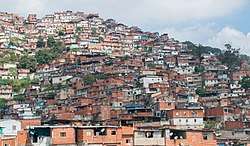

Caracas grew in size, population, and economic importance during Venezuela's oil boom in the early 20th century. In the 1950s, the metropolitan area of Gran Caracas was developed, and the city began an intensive modernization program, funding public buildings, which continued throughout the 1960s and early 1970s.[1] Cultural landmarks, like the University City of Caracas, designed by modernist architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva and declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 2000;[20] the Caracas Museum of Contemporary Art; and the Teresa Carreño Cultural Complex were built, as well as the Caracas Metro and a developed downtown area. Urban development was rapid, leading to the growth of slums on the hillsides surrounding the new city. Much of the city development also fell into disrepair come the end of the 20th century, with the 1980s oil glut and political instability like the Caracazo, meaning maintenance can not be sustained. The economic and social problems persist throughout the capital and country, characterized as the Crisis in Venezuela. Caracas is the most violent city in the world.[1]

Coat of arms

The coat of arms was adopted in 1591. Simón de Bolívar, an ancestor of Venezuelan liberator Simón Bolívar,[21] had been named the first procurator general of the Venezuelan province in 1589. He served as the representative of Venezuela to the Spanish Crown, and vice versa.[22] In 1591, de Bolívar introduced a petition to King Philip II for a coat of arms, which he granted by Royal Cedula on 4 September that year in San Lorenzo. The coat of arms represents the city's name with the red Santiago (St. James') cross. It originally depicted "a brown bear rampant on a field of silver, holding between its paws a golden shell with the red cross of Santiago; and its seal is a crown with five golden points".[23] In the same act, the king declared Caracas as "The Most Noble and Very Loyal City of Santiago de León de Caracas".[24]

The anthem of the city is the Marcha a Caracas, written by the composer Tiero Pezzuti de Matteis with the lyrics by José Enrique Sarabia and approved in 1984.[25]

Geography

Caracas is contained entirely within a valley of the Venezuelan Central Range, and is separated from the Caribbean coast by a roughly 15-kilometre (9 mi) expanse of El Ávila National Park. The valley is relatively small and quite irregular, and the altitude varies from between 870 and 1,043 meters (2,854 and 3,422 ft) above sea level; the historic center lies at about 900 meters (3,000 feet) above sea level.[26] This, along with the rapid population growth, has profoundly influenced the urban development of the city.[27] The most elevated point of the Capital District, wherein the city is located, is the Pico El Ávila, which rises to 2,159 meters (7,083 feet).[26]

The main body of water in Caracas is the Guaire River, which flows across the city and empties into the Tuy River, which is also fed by the El Valle and San Pedro rivers, in addition to numerous streams which descend from El Ávila. The La Mariposa and Camatagua reservoirs provide water to the city.[28][29][30][31] The city is occasionally subject to earthquakes – notably in 1641 and 1967.

Geologically, Caracas was formed in the Late Cretaceous period, with much of the rest of the Caribbean, and sits on what is mostly metamorphic rock. Deformation of the land in this period formed the region.[32]

Climate

Under the Köppen climate classification, Caracas has a mix of tropical savanna climate (Aw) with subtropical highland (Cwb) influences due to its altitude. Caracas is also intertropical, with precipitation that varies between 900 and 1,300 millimeters (35 and 51 inches) (annual), in the city proper, and up to 2,000 millimeters (79 inches) in some parts of the Mountain range. While Caracas is within the tropics, due to its altitude temperatures are generally not nearly as high as other tropical locations at sea level. The annual average temperature is approximately 23.8 °C (75 °F), with the average of the coldest month (January) 22.8 °C (73 °F) and the average of the warmest month (July) 25.0 °C (77 °F), which gives a small annual thermal amplitude of 2.2 °C (4.0 °F).[33]

In the months of December and January abundant fog may appear, in addition to a sudden nightly drop in temperature, until reaching 8 °C (46 °F).[33] This peculiar weather is known by the natives of Caracas as the Pacheco. In addition, nightly temperatures at any time of the year are much (14 to 20 °C) lower than daytime highs and usually do not remain above 24 °C (75 °F), resulting in very pleasant evening temperatures. Hail storms appear in Caracas, although only on rare occasions. Electrical storms are much more frequent, especially between June and October, due to the city being in a closed valley and the orographic action of Cerro El Ávila.[34]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 31.9 (89.4) |

34.1 (93.4) |

35.3 (95.5) |

33.5 (92.3) |

34.4 (93.9) |

32.8 (91.0) |

33.6 (92.5) |

31.5 (88.7) |

32.2 (90.0) |

31.4 (88.5) |

31.2 (88.2) |

30.8 (87.4) |

35.3 (95.5) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 23.3 (73.9) |

23.6 (74.5) |

24.3 (75.7) |

25.0 (77.0) |

25.8 (78.4) |

26.0 (78.8) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.8 (78.4) |

25.5 (77.9) |

25.2 (77.4) |

24.6 (76.3) |

23.8 (74.8) |

24.9 (76.8) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 19.6 (67.3) |

19.7 (67.5) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.2 (70.2) |

22.0 (71.6) |

22.0 (71.6) |

21.7 (71.1) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.9 (71.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

21.3 (70.3) |

20.2 (68.4) |

21.1 (70.0) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 15.9 (60.6) |

15.8 (60.4) |

16.0 (60.8) |

17.5 (63.5) |

18.2 (64.8) |

18.1 (64.6) |

17.9 (64.2) |

18.1 (64.6) |

18.3 (64.9) |

18.4 (65.1) |

18.0 (64.4) |

16.5 (61.7) |

17.4 (63.3) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 7.1 (44.8) |

10.9 (51.6) |

11.4 (52.5) |

12.5 (54.5) |

13.1 (55.6) |

14.9 (58.8) |

14.1 (57.4) |

14.3 (57.7) |

15.5 (59.9) |

13.1 (55.6) |

11.9 (53.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

7.1 (44.8) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 15.3 (0.60) |

13.2 (0.52) |

11.4 (0.45) |

59.2 (2.33) |

81.7 (3.22) |

134.1 (5.28) |

118.4 (4.66) |

123.8 (4.87) |

115.4 (4.54) |

126.3 (4.97) |

72.6 (2.86) |

41.4 (1.63) |

912.8 (35.94) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 6 | 4 | 3 | 7 | 13 | 19 | 19 | 18 | 15 | 15 | 13 | 10 | 142 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 73.7 | 74.2 | 73.0 | 76.3 | 75.4 | 75.1 | 74.1 | 74.0 | 74.9 | 74.7 | 73.7 | 74.7 | 74.5 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 229.4 | 217.5 | 235.6 | 183.0 | 182.9 | 183.0 | 210.8 | 217.0 | 213.0 | 210.8 | 210.0 | 213.9 | 2,506.9 |

| Source 1: Instituto Nacional de Meteorología e Hidrología (INAMEH)[35][36] | |||||||||||||

| Source 2: World Meteorological Organization (rainfall data),[37] Hong Kong Observatory (sun only),[38] NOAA(extremes)[39] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

According to the population census of 2011 the Caracas proper (Distrito Capital) is over 1.9 million inhabitants,[40] while that of the Metropolitan District of Caracas is estimated at 2.9 million as of 2011. The majority of the population is mixed-race, typically with varying degrees of European, African, Indigenous and occasional Asian ancestry. There is a noteworthy Afro-Venezuelan community. Additionally, the city has a large number of both European Venezuelans and Asian Venezuelans who descend from the massive influx of various immigrants Venezuela received from all across Eurasia during the 20th century; in particular are descendants of Spaniards, Portuguese, Italians, Chinese, Colombians, Germans, Syrians and Lebanese people.[40][41] In 2020, the poorest 55% of the Caracas population lived on about a third of its land, in poorly-planned slums that are generally dangerous to live in and access.[42]

Crime

Venezuela and its capital, Caracas, are reported to both have among the highest per capita murder rates in the world. Caracas is the city with the highest homicide rate in the world outside of a warzone, with a 2016 rate of around 120 murders per 100,000 people.[43][44][45][46][47][48] Most murders and other violent crimes go unsolved, with estimates of the number of unresolved crimes as high as 98%.[49][50][51] The U.S. Department of State and British Foreign and Commonwealth Office have issued travel warnings for Venezuela (especially Caracas) due to high rates of crime.[52][53]

Economy

Businesses that are located in Caracas include service companies, banks, and malls, among others. It has a largely service-based economy, apart from some industrial activity in its metropolitan area.[7] The Caracas Stock Exchange and Petróleos de Venezuela (PDVSA) are headquartered here. PDVSA, a state-run organization, is the largest company in Venezuela,[54] and negotiates all the international agreements for the distribution and export of petroleum.[55] When it existed, the airline Viasa had its headquarters in the Torre Viasa.[56][57]

Several international companies and embassies are located in El Rosal and Las Mercedes, in the Caracas area. The city also serves as a hub for communication and transportation infrastructure between the metropolitan area and the rest of the country. Important industries in Caracas include chemicals, textiles, leather, food, iron, and wood products. There are also rubber and cement factories.[58] Its nominal GDP is US$70 billion and the GDP (PPP) per capita is US$24,000.[59]

A 2009 United Nations survey reported that the cost of living in Caracas was 89% of that of the survey's baseline city, New York.[60] However, this statistic is based upon a fixed currency-exchange-rate of 2003 and might not be completely realistic, due to the elevated inflation rates of the last several years.[61]

Tourism

In 2013, the World Economic Forum evaluated countries in terms of how successful they were in advertising campaigns to attract foreign visitors. Out of the 140 countries evaluated, Venezuela came last. A major factor that has contributed to the lack of foreign visitors has been poor transport for tourists. Venezuela has limited railway systems and airlines. High crime rates and the negative attitude of the Venezuelan population towards tourism also contributed to the poor evaluation.[62]

In an attempt to attract more foreign visitors, the Venezuelan Ministry of Tourism invested in multiple hotel infrastructures. The largest hotel investment has been in the Hotel Alba Caracas. The cost for the general maintenance of the north and south towers of the hotel is approximately 231.5 million Venezuelan bolivars. Although the Venezuelan Ministry of Tourism has taken the initiative to recognize the importance of the tourism industry, the Venezuelan government has not placed the tourism industry as an economic priority. In 2013, the budget for the Ministry of Tourism was only 173.8 million bolivars, while the Ministry of the Youth received approximately 724.6 million bolivars.[62] The tourism industry in Venezuela contributes approximately 3.8 percent of the country GDP. The World Economic Forum predicts Venezuela's GDP to rise to 4.2 percent by 2022.[63]

Government

On 8 March 2000, the year after a new constitution was introduced in Venezuela, it was decreed in Gaceta Official N° 36,906 that the Metropolitan District of Caracas would be created and that some of the powers of the Libertador, Chacao, Baruta, Sucre, and El Hatillo municipalities would be delegated to the Alcaldía Mayor, physically located in the large Libertador municipality, in the center of the city.[64] The Metropolitan District of Caracas was suppressed on 20 December 2017 by the Constituent National Assembly of Venezuela.[65]

Landmarks

Culture

Caracas is Venezuela's cultural capital, with many restaurants, theaters, museums, and shopping centers. The city is home to many immigrants from Spain, Italy, Portugal, the Middle East, Germany, China, and other Latin American countries.[66][67][68][69]

Sports

Professional sports teams in the city include the football clubs Caracas Fútbol Club, Deportivo Petare, Atlético Venezuela, SD Centro Italo Venezolano, Estrella Roja FC and Deportivo La Guaira. Deportivo Petare has reached the semi-finals of international tournaments, such as the Copa Libertadores, while the Caracas Fútbol Club has reached the quarterfinals. Baseball teams Tiburones de La Guaira and Leones del Caracas play at University Stadium, with a capacity of nearly 26,000 spectators.[70]

The football stadiums in the city include the Olympic Stadium, home to Caracas Fútbol Club and Deportivo La Guaira, with a capacity of 30,000 spectators, and the Brígido Iriarte Stadium, home to Atlético Venezuela, with a capacity of 12,000 spectators. In basketball, the Cocodrilos de Caracas play their games in the Poliedro de Caracas in the El Paraíso neighborhood.

Caracas is the seat of the National Institute of Sports and of the Venezuelan Olympic Committee. The city hosted the 1983 Pan American Games.

Education

Central University of Venezuela

The Central University of Venezuela (Universidad Central de Venezuela, UCV) is a public university founded in 1721: it is the oldest university in Venezuela.[71] The university campus was designed by architect Carlos Raúl Villanueva and declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2000.[72]

Simón Bolívar University

The Simón Bolívar University (Universidad Simón Bolívar, USB) is a public institution in Caracas that focuses on science and technology. Its motto is "La Universidad de la Excelencia" ("University of Excellence").

Other universities

- Academia Militar de Venezuela

- Escuela de Formación de Oficiales de las Fuerzas Armadas de Cooperación

- Universidad Católica Andrés Bello

- Universidad Nacional Experimental de la Gran Caracas

- Universidad Metropolitana

- Universidad Nacional Experimental de las Artes

- Universidad Monteávila

- Universidad Nueva Esparta

- Universidad Santa Maria

- Universidad Alejandro de Humboldt

- Universidad Nacional Experimental de las Fuerzas Armadas

- Universidad Nacional Experimental Simón Rodríguez

- Universidad Bolivariana de Venezuela

- Universidad José María Vargas

- Universidad Pedagógica Experimental Libertador

- Universidad Experimental Politécnica Antonio José de Sucre

International schools

- British School of Caracas

- Colegio Internacional de Caracas

- Escuela Campo Alegre

- International Christian School

- Tomchei Tmimim

- Lycée Français de Caracas - Colegio Francia

Transportation

The Caracas Metro has been in operation since 27 March 1983. With 4 lines, 47 stations and about 10 more to be constructed. It covers a great part of the city and also has an integrated ticket system that combines the route of the Metro with those offered by the Metrobús, a bus service of the Caracas Metro. In 2010, the first segment of a new ariel cable car system opened, Metrocable[73] which feeds into the larger metro system.

Buses are the main means of mass transportation. There are two bus systems: the traditional system and the Metrobús. Other transportation services include the IFE train to and from the Tuy Valley cities of Charallave and Cúa; the Simón Bolívar International Airport, the biggest and most important in the country; the metro additional services Caracas Aerial Tramway and Los Teques Metro (connecting Caracas with the suburban city of Los Teques); and the Generalissimo Francisco de Miranda Air Base used by military aviation and government airplanes.

Notable people

International relations

Twin towns and Sister Cities

Caracas is twinned with:

- Honolulu, United States[74]

- New Orleans, United States[74]

- Melilla, Spain[75]

- Rosario, Argentina, since 1998[76]

- Santa Cruz de Tenerife, Spain, since 1981[77]

Union of Ibero-American Capital Cities

Caracas is part of the Union of Ibero-American Capital Cities[78] from 12 October 1982 establishing brotherly relations with the following cities:

- Andorra la Vella, Andorra

- Asunción, Paraguay

- Bogotá, Colombia

- Buenos Aires, Argentina

- Caracas, Venezuela

- Guatemala City, Guatemala

- Havana, Cuba

- Quito, Ecuador

- La Paz, Bolivia

- Lima, Peru

- Lisbon, Portugal

- Madrid, Spain[79]

- Managua, Nicaragua

- Mexico City, Mexico

- Montevideo, Uruguay

- Panama City, Panama

- Rio de Janeiro, Brazil

- San Jose, Costa Rica

- San Juan, Puerto Rico, United States

- San Salvador, El Salvador

- Santiago, Chile

- Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic

- Tegucigalpa, Honduras

See also

Notes and references

- Straka, Tomás; Guzmán Mirabal, Guillermo; Cáceres, Alejandro E. (2017). Historical dictionary of Venezuela. Rudolph, Donna Keyse (Third ed.). Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-5381-0949-6. OCLC 993810331.

- "Postal Codes in Caracas". Páginas Amarillas Cantv. Archived from the original on 12 April 2018. Retrieved 30 December 2015.

- "Caracas, Presente y Futuro: Ideas para Transformar una Ciudad". Alcaldía de Caracas. 1995.

- Martín Frechilla, Juan José (2004). Diálogos reconstruidos para una historia de la Caracas moderna. Caracas, Venezuela: CDCH UCV.

- "Plaza Venezuela (Caracas) - Ciberturista". Ciberturista (in Spanish). 20 January 2010. Archived from the original on 15 May 2018. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- Rodríguez, Verónica; Valero, Carla. "Una rayuela que se borra y se vuelve a dibujar cada día. Semblanza de lugar sobre la transformación urbanística y cultural de Sabana Grande" (PDF). Tesis de Grado. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 September 2016. Retrieved 15 March 2018.

- "Caracas". Caracas.eluniversal.com. Archived from the original on 3 September 2008. Retrieved 30 April 2010.

- "The Skyscraper Center". www.skyscrapercenter.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2018. Retrieved 3 May 2018.

- "Caracas The Skyscraper Center". www.skyscrapercenter.com. Archived from the original on 2 May 2018. Retrieved 1 May 2018.

- Valentina Quintero. 1998. Venezuela. Corporación Venezolana de Turismo. Caracas. 118p.

- "The Most Dangerous Cities in the World".

- Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Ferry, Robert J. (1989). The colonial elite of early Caracas: formation & crisis, 1567-1767. Berkeley, Calif.: University of California Press. ISBN 0-585-28540-3. OCLC 45728929.

- Layrisse, Miguel; Wilbert, Johannes; Arends, Tulio (1958). "Frequency of blood group antigens in the descendants of Guayquerí Indians". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 16 (3): 307–318. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330160304. ISSN 0002-9483. PMID 13649899.

- McCudden, Mary Rose (May 2014). Britannica Student Encyclopedia : an A to Z Encyclopedia. [Chicago, Illinois]. p. 36. ISBN 978-1-62513-172-0. OCLC 882262198.

- John Lombardi, Venezuela, Oxford, England, 1982, p 72.

- "George Somers, Amyas Preston and the Burning of Caracas". The Bermudian. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

- "The connection between the United Utates independence and the hispanic american independence movement, and the role played by some key books published at the beginning of the xix century" (PDF). allanbrewercarias.net. Retrieved 29 July 2019.

- Maurice Wiesenthal, The History and Geography of a Valley, 1981.

- "Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas". UNESCO. Retrieved 28 May 2010.

- Sánchez, George Isidore (1963). The Development of Education in Venezuela. U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare, Office of Education. p. 13.

- de Oviedo y Baños, José (2018). CONQUEST AND SETTLEMENT OF VENEZUELA. University of California Press. pp. 260–261. ISBN 978-0-520-30135-1. OCLC 1031451450.

- de Oviedo y Baños, José (1987). The conquest and settlement of Venezuela. Varner, Jeannette Johnson. Berkeley: University of California Press. pp. 190–191. ISBN 0-520-05851-8. OCLC 14240336.

- Rowe, John Carlos (2000). Literary culture and U.S. imperialism : from the Revolution to World War II. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 413. ISBN 978-0-19-535123-1. OCLC 71801841.

- "Himno a Caracas". htr.noticierodigital.com. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Parsons, James J. (1982). "The Northern Andean Environment". Mountain Research and Development. 2 (3): 253–264. doi:10.2307/3673089. JSTOR 3673089.

- Morris, A.S. (1978). "Urban Growth Patterns in Latin America with Illustrations from Caracas". Urban Studies. 15 (3): 299–312. doi:10.1080/713702382. ISSN 0042-0980.

- "Guaire River". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Jaffe, Rudolf; Leal, Ivan; Alvarado, Jose; Gardinali, Piero; Sericano, José (1 December 1995). "Pollution effects of the Tuy River on the central Venezuelan coast: Anthropogenic organic compounds and heavy metals in Tivela mactroidea". Marine Pollution Bulletin. 30 (12): 820–825. doi:10.1016/0025-326X(95)00087-4. ISSN 0025-326X.

- Aloui, Fethi; Dinçer, İbrahim (22 August 2018). Exergy for a better environment and improved sustainability. 2, Applications. Cham, Switzerland. p. 716. ISBN 978-3-319-62575-1. OCLC 1049802575.

- Steward, Julian Haynes (1946). Handbook of South American Indians. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 475.

- Dengo, Gabriel (1 January 1953). "Geology of the Caracas Region, Venezuela". GSA Bulletin. 64 (1): 7–40. Bibcode:1953GSAB...64....7D. doi:10.1130/0016-7606(1953)64[7:GOTCRV]2.0.CO;2. ISSN 0016-7606.

- "Weather Base – World Weather – Average Conditions – Caracas". BBC. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ""Llegó Pacheco" con su historia y origen". Televen (in Spanish). 11 December 2017. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Estadísticos Básicos Temperaturas y Humedades Relativas Máximas y Mínimas Medias" (PDF). INAMEH (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "Estadísticos Básicos Temperaturas y Humedades Relativas Medias" (PDF). INAMEH (in Spanish). Archived from the original (PDF) on 15 June 2013. Retrieved 31 July 2012.

- "World Weather Information Service – Caracas". World Meteorological Organization. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- "Climatological Information for Caracas, Venezuela". Hong Kong Observatory. Archived from the original on 4 October 2014. Retrieved 16 October 2012.

- "Caracas-La-Carlota Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 15 January 2013.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 October 2012. Retrieved 2010-04-30.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Censo Nacional Deciembre 2014

- Hernández, Felipe; Kellett, Peter William; Allen, Lea K. (2010). Rethinking the informal city : critical perspectives from Latin America. New York: Berghahn Books. p. 119. ISBN 978-1-84545-972-7. OCLC 647933862.

- "List of cities by murder rate". seguridadjusticiaypaz.org.mx. Retrieved 26 January 2016.

- "Most Dangerous Cities in the World". WorldAtlas.

- Tait, Robert (28 January 2016). "Caracas, Venezuela named as the world's most violent city". The Telegraph. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Grillo, Ioan. "Venezuela's Murder Epidemic Rages on Amid State of Emergency". TIME. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Tegel, Simeon. "Venezuela's capital is world's most murderous city". USA Today. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- "Caracas World's Most Violent City: Report". Insight Crime. 27 March 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Woody, Christopher. "Venezuela admits homicides soared to 60 a day in 2016, making it one of the most violent countries in the world". Business Insider. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- "'98% Impunity Rate in Venezuela': Opposition". InSight crime. Archived from the original on 26 September 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- Mendoza, Samuel. "Impunity and insecurity go hand in hand in Venezuela". El Universal. Archived from the original on 23 April 2017. Retrieved 22 April 2017.

- "Venezuela Travel Warning". U.S. Department of State. Archived from the original on 16 June 2017. Retrieved 16 June 2017.

- "Venezuela travel advice". GOV.UK. Retrieved 6 November 2018.

- "Sitio Web PDVSA". Pdvsa.com. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "Petróleos de Venezuela S.A." PDVSA. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- "World Airline Directory." Flight International. 30 March 1985. 130." Retrieved on 17 June 2009.

- "World Airline Directory." Flight International. 26 March 1988. 125.

- "CIA – The World Factbook". Cia.gov. Retrieved 16 March 2012.

- "The Online Journal of McKinsey & Company". McKinsey Quarterly. Archived from the original on 14 July 2012. Retrieved 12 March 2013.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 December 2009. Retrieved 2009-09-18.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- En_eco_art_venezuela With The H_13A884453 – 2007 – El Universal Archived 12 January 2014 at the Wayback Machine

- Blanke, Jennifer; Chiesa, Thea (2013). "The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2013" (PDF). World Economic Forum. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- MARTÍNEZ RODRÍGUEZ, M. (2013). Venezuela: un destino nada chévere. Debates IESA, 18(4), 73–75.

- Goldfrank, Benjamin (2011). Deepening Local Democracy in Latin America: Participation, Decentralization, and the Left. Penn State Press. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-271-07451-1.

- "ANC aprobó supresión y liquidación del Área Metropolitana de Caracas" (in Spanish). El Nacional. 20 December 2017. Retrieved 21 April 2018.

- Ingham, James (20 April 2007). "Americas | Airships to tackle Caracas crime". BBC News. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- "Venezuela". Travel.state.gov. Archived from the original on 11 January 2014. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- "Venezuela Warnings or Dangers – Travel Guide". VirtualTourist.com. Archived from the original on 3 May 2009. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- Feinman, Sacha (27 November 2006). "Crime and class in Caracas. – By Sacha Feinman – Slate Magazine". Slate.com. Retrieved 7 July 2009.

- "Estadio Universitario". www.ucv.ve. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Abner J. Colmenares, "Urban and Real Estate Development of the Central University of Venezuela's Rental Zone", in Wim Wiewel and David C. Perry, eds., Global Universities and Urban Development: Case Studies and Analysis (Armonk NY: M.E. Sharpe, 2008), 181. ISBN 9780765638922

- "Ciudad Universitaria de Caracas". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. Unesco. Archived from the original on 25 March 2019. Retrieved 25 March 2019.

- "Caracas Metro Cable". www.urbanrail.net.

- "Caracas, Venezuela". Sister Cities International. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 9 February 2015.

- Terra. "Hermanamiento de Melilla con Caracas".

- "Town Twinning Agreements". Municipalidad de Rosario – Buenos Aires 711. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- Santa Cruz más. "Ciudades hermanadas con Santa Cruz de Tenerife". Archived from the original on 16 July 2011. Retrieved 21 October 2015.

- "Declaración de Hermanamiento múltiple y solidario de todas las Capitales de Iberoamérica (12-10-82)" (PDF). 12 October 1982. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2013. Retrieved 2015-03-12.

- "Madrid International". Ayuntamiento de Madrid. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015. Retrieved 22 July 2009.

.jpg)