Aomori Prefecture

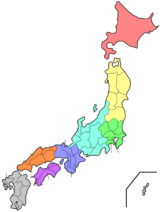

Aomori Prefecture (青森県, Aomori-ken) is a prefecture of Japan located in the Tōhoku region.[1] The prefecture's capital, largest city, and namesake is the city of Aomori.[2] The prefecture was made out of the northern part of the Mutsu Province during the Meiji Restoration. The prefecture, which is bordered on the east by the Pacific Ocean, Iwate Prefecture to the southeast, Akita Prefecture to the southwest, the Sea of Japan to the west, and the Tsugaru Strait to the north, is the northernmost prefecture on Japan's main island, Honshu.

Aomori Prefecture 青森県 | |

|---|---|

| Japanese transcription(s) | |

| • Japanese | 青森県 |

| • Rōmaji | Aomori-ken |

Flag  Symbol | |

| |

| Country | Japan |

| Region | Tōhoku |

| Island | Honshu |

| Capital | Aomori |

| Subdivisions | Districts: 8, Municipalities: 40 |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Shingo Mimura |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9,645.64 km2 (3,724.20 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 8th |

| Population (June 1, 2019) | |

| • Total | 1,249,314 |

| • Rank | 31st |

| • Density | 130/km2 (340/sq mi) |

| ISO 3166 code | JP-02 |

| Website | www |

| Symbols | |

| Bird | Bewick's swan (Cygnus bewickii) |

| Flower | Apple blossom (Malus domestica) |

| Tree | Hiba (Thujopsis dolabrata) |

Aomori Prefecture is the 8th largest prefecture, with an area of 9,645.64 square kilometers (3,724.20 sq mi), and the 31st most populous prefecture, with more than 1.2 million people. Approximately 45 percent of Aomori Prefecture's residents live in its two core cities, Aomori and Hachinohe that lie on coastal plains. The majority of the prefecture is covered in forested mountain ranges, with population centers occupying valleys and plains. Aomori is the third most populous prefecture in the Tōhoku region, after Miyagi Prefecture and Fukushima Prefecture. Mount Iwaki, an active stratovolcano, is the prefecture's highest point, at almost 1,624.7 meters (5,330 feet).

Geography

Aomori Prefecture is the northernmost prefecture in the Tōhoku region, lying on the northern end of the island of Honshu. It faces Hokkaido from across the Tsugaru Strait. It borders Akita and Iwate in the south. The prefecture is flanked by the Pacific Ocean to the east and the Sea of Japan to the west with the Tsugaru Strait linking those bodies of water to the north of the prefecture. Oma, at the northwestern tip of the axe-shaped Shimokita Peninsula, is the northernmost point of Honshu. The Shimokita and Tsugaru Peninsulas enclose Mutsu Bay. Between those peninsulas lies the smaller Natsudomari Peninsula, the northern end of the Ōu Mountains. The three peninsulas are prominently visible in the prefecture's symbol, a stylized map.[3]

Lake Towada, a crater lake, straddles Aomori's boundary with Akita. Oirase River flows easterly from Lake Towada. The Shirakami Mountains are located in western Aomori and contain the last of the virgin beech tree forest which is home to over 87 species of birds.[3]

As of 31 March 2019, 12% of the total land area of the prefecture was designated as Natural Parks, namely the Towada-Hachimantai and Sanriku Fukkō National Parks; Shimokita Hantō and Tsugaru Quasi-National Parks; and Asamushi-Natsudomari, Ashino Chishōgun, Iwaki Kōgen, Kuroishi Onsenkyō, Nakuidake, Ōwani Ikarigaseki Onsenkyō, and Tsugaru Shirakami Prefectural Natural Parks; and Mount Bonju Prefectural Forest.[4][5]

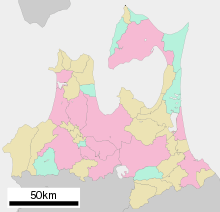

Cities

Towns and villages

City Town Village

These are the towns and villages in each district:

- Higashitsugaru District

- Hiranai

- Imabetsu

- Sotogahama

- Yomogita

- Kamikita District

- Kitatsugaru District

- Minamitsugaru District

- Nakatsugaru District

- Nishitsugaru District

- Sannohe District

- Shimokita District

- Higashidōri

- Kazamaura

- Ōma

- Sai

Mergers

Climate

The climate of Aomori Prefecture is relatively cool for the most part. It has four distinct seasons with an average temperature of 10 °C. Variations in climate exist between the eastern (Pacific Ocean side) and the western (Japan Sea side) parts of the prefecture. This is in part due to the Ōu Mountains that run north to south and divide the two regions. The western side is subject to heavy monsoons and little sunshine which results in heavy snowfall during the winter. The eastern side receives little sunlight during the summer months, June through August, with temperatures staying relatively low. The lowest recorded temperature during the winter is -9.3 °C, and the highest recorded temperature during the summer is 33.1 °C.[3]

History

Jōmon period

The oldest evidence of pottery in Japan was found at the Odai Yamamoto I site in the town of Sotogahama in the northwestern part of the prefecture. The relics found there suggest that the Jōmon period began about 15,000 years ago.[7] By 7,000 BCE fishing cultures had developed along the shores of the prefecture which were three meters higher than the present day shoreline.[8] Around 3,900 BCE settlement at the Sannai-Maruyama site in the present-day city of Aomori began.[9] The settlement shows evidence the wide interaction between the site's inhabitants and people from across Jōmon period Japan, including Hokkaido and Kyushu.[7] The settlement of Sannai-Maruyama ended around 2300 BCE due to unknown reasons. Its abandonment was likely due to the population's subsistence economy being unable to result in sustained growth, with its end being spurred on by the reduced amount of natural resources during the neoglaciation.[10] The Jōmon period continued up to 300 BCE in present-day Aomori Prefecture at the Kamegaoka site in the city of Tsugaru where the Shakōki-dogū was found.[7]

Yayoi period to Heian period

During the Yayoi period the area that would become Aomori Prefecture was impacted by the migration of settlers from continental Asia to a lesser extent than the rest of Japan to the south and west of the region. The region, known then as Michinoku, was inhabited by the Emishi. It is not clear if the Emishi were the descendants of the Jōmon people, a group of the Ainu people, or if both the Ainu and Emishi were descended from the Jōmon people. The northernmost tribe of the Emishi that inhabited what would become Aomori Prefecture was known as the Tsugaru.[11] The Emishi were slowly subdued by the Imperial Court in Kyoto before being incorporated into Mutsu Province by the Northern Fujiwara around 1094.[12] The Northern Fujiwara set up the port settlement Tosaminato in present-day Goshogawara to develop trade between their lands, Kyoto, and continental Asia.[13] The Northern Fujiwara were deposed in 1189 by Minamoto no Yoritomo who would go on to establish the Kamakura shogunate.[14]

Kamakura period

Minamoto no Yoritomo incorporated Mutsu Province into the holdings of the Kamakura shogunate. Nanbu Mitsuyuki was awarded vast estates in Nukanobu District after he had joined Minamoto no Yoritomo at the Battle of Ishibashiyama and the conquest of the Northern Fujiwara. Nanbu Mitsuyuki built Shōjujidate Castle in what is now Nanbu, Aomori. The area was dominated by horse ranches, and the Nanbu grew powerful and wealthy on the supply of warhorses. These horse ranches were fortified stockades, numbered one through nine (Ichinohe through Kunohe), and were awarded to the six sons of Nanbu Mitsuyuki, forming the six main branches of the Nanbu clan.

Meiji era to World War II

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% p.a. |

| 1880 | 475,413 | — |

| 1890 | 545,026 | +1.38% |

| 1903 | 665,691 | +1.55% |

| 1913 | 764,485 | +1.39% |

| 1920 | 756,454 | −0.15% |

| 1925 | 812,977 | +1.45% |

| 1930 | 879,914 | +1.60% |

| 1935 | 967,129 | +1.91% |

| 1940 | 1,000,509 | +0.68% |

| 1945 | 1,083,250 | +1.60% |

| 1950 | 1,282,867 | +3.44% |

| 1955 | 1,382,523 | +1.51% |

| 1960 | 1,426,606 | +0.63% |

| 1965 | 1,416,591 | −0.14% |

| 1970 | 1,427,520 | +0.15% |

| 1975 | 1,468,646 | +0.57% |

| 1980 | 1,523,907 | +0.74% |

| 1985 | 1,524,448 | +0.01% |

| 1990 | 1,482,873 | −0.55% |

| 1995 | 1,481,663 | −0.02% |

| 2000 | 1,475,728 | −0.08% |

| 2005 | 1,436,657 | −0.54% |

| 2010 | 1,373,339 | −0.90% |

| 2015 | 1,308,649 | −0.96% |

| source:[15] | ||

In 1868 Mutsu Province was broken up into five provinces in the aftermath of the Boshin War, with its namesake province, Rikuō occupying what would later become Aomori Prefecture and the northwestern corner of Iwate Prefecture. In 1871 Rikuō Province was abolished and divided, establishing today's Aomori Prefecture.[16] The town of Aomori was established in 1889. The town was incorporated as a city in 1898 with a population of 28,000. On 3 May 1910, a fire broke out in the Yasukata district. Fanned by strong winds, the fire quickly devastated the whole city. The conflagration claimed 26 lives and injured a further 160 residents. It destroyed 5,246 houses and burnt 19 storage sheds and 157 warehouses. At 10:30 p.m. on 28 July 1945, a squadron of American B29 bombers bombed over 90% of the city.

1945 to present

Radio Aomori made its first broadcast in 1951. Four years later, the first fish auctions were held. 1958 saw the completion of the Municipal Fish Market as well as the opening of the Citizen's Hospital. In the same year, the Tsugaru Line established a rail connection with Minmaya Village at the tip of the peninsula.

Various outlying towns and villages were incorporated into the growing city and with the absorption of Nonai Village in 1962, Aomori became the largest city in the prefecture.

In March 1985, after 23 years of labor and a financial investment of 700 billion yen, the Seikan Tunnel finally linked the islands of Honshū and Hokkaidō, thereby becoming the longest tunnel of its kind in the world. Almost exactly three years later, on March 13, railroad service was inaugurated on the Tsugaru Kaikyo Line.

That same day saw the end of the Seikan ferry rail service. During their 80 years of service, the familiar ferries of the Seikan line sailed between Aomori and Hakodate some 720,000 times, carrying 160 million passengers.

In April 1993, Aomori Public College opened. In August 1994, Aomori City made an "Education, Culture and Friendship Exchange Pact" with Kecskemét in Hungary. One year later, a similar treaty was signed with Pyongtaek in South Korea, and cultural exchange activities began with exchanges of woodblock prints and paintings.

In April 1995, Aomori Airport began offering regular international air service to Seoul, South Korea, and Khabarovsk, Russia; however, the flights to Khabarovsk were discontinued in 2004.[17]

In June 2007, four North Korean defectors reached Aomori Prefecture, after having been at sea for six days, marking the second known case ever where defectors have successfully reached Japan by boat.[18]

In March 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake struck the east coast of Japan. The southeastern coast of Aomori Prefecture was affected by the resulting tsunami. Buildings along harbors were damaged along with boats thrown about in the streets.[19]

Economy

Like much of the Tōhoku Region, Aomori Prefecture remains dominated by primary sector industries such as farming, forestry, and fishing.

Aomori Prefecture is Japan's largest producer of apples, accounting for 54 percent of Japan's total apple production. The cultivation of apples in the prefecture began in 1875 when the prefecture was given three varieties of western origin to grow. The apples are consumed within Japan and exported to the United States, China, Taiwan, and Thailand.[3] Aomori also boasts being the home to Hakkōda cattle, a rare, region-specific breed of Japanese Shorthorn.[20] The town of Gonohe has a long history as a breeding center for horses of exceptional quality, popular among the samurai. With the decline of the samurai, Gonohe's horses continued to be bred for their meat. The lean horse meat is coveted as a delicacy, especially when served in its raw form, known as Basashi (馬刺し). The Aomori coast along Mutsu Bay is a large source of scallops, but they are particularly a specialty of the town Hiranai where the calm water around Natsudomari Peninsula makes a good home for them.[21]

Aomori Prefecture generates the largest amount of wind energy, with large wind farms located on the Shimokita Peninusla. The peninsula is also home to the inactive Rokkasho Reprocessing Plant. The city of Hachinohe is home to the Pacific Metals Company, a manufacturer of ferronickel products.[3]

Tourism

Big Buddha

Aomori Shōwa Daibutsu (昭和大仏), also known as the Big Buddha in Aomori, is the tallest seated Buddha in Japan. Located at Seiryū-ji (Blue-Green Dragon Temple) in Aomori City, this statue was built as a symbol of gratitude for WWII soldiers as well as a symbol for Buddha's teachings. The Seiryuu-ji temple itself is relatively new and was founded in 1982 by a priest named Ryuko Oda. The temple grounds have traditional style Japanese architecture. In 1984, the Big Buddha statue was built, weighing in at 220 tons and is 21.35 metres (70.0 ft) tall. Underneath the Buddha there is a circular hallway with many paintings, pictures and small statues. A Buddha shrine with an offering table can also be found inside.[22]

Hirosaki Castle

Hirosaki Castle, a castle in Hirosaki known for its gardens' cherry blossoms.

Jesus Christ's grave legend

There is a localized Japanese legend that Jesus Christ did not die on the cross but made his way to Shingō, Aomori where he became a rice farmer, married, and had a family.[23] The legend owes its existence to a supposed 1930s discovery of what were claimed to be "ancient Hebrew documents detailing Jesus's life and death in Japan". The legend also claims that his grave is located in Aomori.[24]

This legend, and the documents it originated from have largely been dismissed as a hoax,[23] but the tourist attraction still persists, along with a traditional song and dance to placate the spirit of Jesus. The meaning of the song though has been lost over time.[25]

Shimokita Geopark

Mount Osore

Mount Osore, the Mountain of Dread, is near Mutsu on the Shimokita Peninsula. This is one of three mountains in Japan that is dedicated to Buddha. The Japanese believe the souls of the dead reside here, and during the summer and autumn festivals many Japanese and tourists travel to this mountain.

Mutsu Bay

Wild horses can be seen at Cape Shiriya and Shipwreck Beach. The peninsula that forms the bay is known as Shimokita Peninsula or "The Hatchet".

Towada-Hachimantai National Park

Hakkōda Mountains

The Hakkōda Mountains in Aomori provide excellent hiking in the warmer seasons. However, the winter of 1902 proved disastrous to 199 of 210 soldiers who died during a military exercise in the area in deep snow.

Lake Towada

Lake Towada, a caldera, lies on the boundary between Akita and Aomori Prefectures. During the summer, firework displays light up the sky and reflect off the water offering a spectacular show. Oirase Gorge lies near Lake Towada and is a popular location for hiking.

Oirase River

The upper reaches of the river form a scenic gorge with numerous rapids and waterfalls, it is one of the 100 Soundscapes of Japan.[26]

Tsugaru Quasi-National Park

Juniko Lakes

Located in the town of Fukaura, the name means “twelve lakes” despite the fact that there are 33. One unique characteristic is the lakes' brilliant colors; one in particular, Aoike Lake, is a rich blue color.

Shirakami-Sanchi

A UNESCO World Heritage Site, this mountainous area includes the last virgin forest of Siebold's beech which once covered most of northern Japan. The area straddles both Akita and Aomori prefectures. The tract that covers 169.7 square kilometers (65.5 sq mi) was included in the list of World Heritage Sites in 1993. Fauna found in the area includes Japanese black bear, the Japanese serow, Japanese macaque, and 87 species of birds.

Other places of interest

- Aomori Museum of Art

- Aomori Prefecture Tourist Center

- Aomori Bay Bridge

- Aomori City Forestry Museum

- Aomori Prefectural Museum

- Aomori City History and Folk Arts Museum

- Hakkoda Ship

- Munakata Shiko Memorial Museum of Art

- Nebuta Museum Wa Rasse

- Sannai-Maruyama site

- Towada Art Center

Military

Aomori Prefecture is host to the Misawa Air Base, the only combined, joint U.S. service installation in the western Pacific servicing Army, Navy, and Air Force, as well as the Japan Self-Defense Forces.

On 20 February 2018 a U.S. Air Force F-16 fighter jet caught fire in flight. The pilot dumped two fuel tanks into Lake Ogawara in eastern Aomori Prefecture.[27]

Culture

Aomori is well known for its tradition of Tsugaru-jamisen, a virtuosic style of shamisen playing. It is also where the decorative embroidery style, kogin-zashi, originated.[28]

Festivals

Aomori Prefecture boasts a variety of festivals year round offering a unique look into northern Japan. Spring is the cherry blossom festival and is celebrated throughout Japan by gathering together to view the blooming cherry blossoms. Summer and autumn hold many distinct festivals with bright lights, floats, dancing and music. Winter is centered on snow festivals where one can view ice sculptures and enjoy Japanese cuisine inside an ice hut.

|

|

Transportation

Airports

There are two airports located within the Aomori Prefecture. Both airports are relatively small, though Aomori Airport offers regular international flights to South Korea and Taiwan, seasonal flights to China, and chartered flights to Thailand, in addition to domestic flights.[33]

Railway

Stations

The following major stations are located in Aomori Prefecture.

Lines

The following lines, operated by East Japan Railway Company (JR East), run through Aomori Prefecture.

Road

Expressways

National highways

Education

Universities

- Aomori Chuo Gakuin University

- Aomori Public University

- Aomori University

- Aomori University of Health and Welfare

- Hachinohe Gakuin University

- Hachinohe Institute of Technology

- Hirosaki Gakuin University

- Hirosaki University

- Hirosaki University of Health and Welfare

- Tohoku Women's College

- Kitasato University (Towada Campus)

Sports

Aomori Prefecture hosted the 2003 Asian Winter Games.

Major professional teams

| Club | Sport | League | Stadium and city |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aomori Curling Club | Curling | Japan Curling Association | Aomori |

| Aomori Wat's | Basketball | B.League (East Second Division) | Maeda Arena, Aomori |

| ReinMeer Aomori | Association football | Japan Professional Football League (JFL) | Maeda Arena, Aomori |

| Tohoku Free Blades | Ice hockey | Asia League Ice Hockey | Flat Arena, Hachinohe |

| Vanraure Hachinohe | Association football | Japan Professional Football League (J3 League) | Prifoods Stadium, Hachinohe |

Minor professional and amateur teams

| Club | Sport | League | Stadium and city |

|---|---|---|---|

| Blancdieu Hirosaki FC | Association football | Tohoku Soccer League (Division 1) | Hirosaki Sports Park, Hirosaki |

| Hachinohe Reds | Ice hockey | Japan Women's Ice Hockey League | Tanabu Ice Hockey Arena, Hachinohe |

| Hirosaki Areds | Baseball | Japan Amateur Baseball Association | Hirosaki |

| King Blizzard | Baseball | Japan Amateur Baseball Association | Goshogawara |

Prefectural symbols

The Aomori prefectural symbol is a stylized map of the prefecture, showing the crown of Honshū: the Tsugaru, Natsudomari and Shimokita Peninsulas.

Dialects

According to Ken Cannon, there are three major dialects spoken in Japan; standard Japanese, Kansai dialect and Tōhoku dialect . Tohoku dialect, or Tohoku-ben, is found in northern Japan and is spoken between farmers and country folks. This dialect is also referred to as "zuu zuu-ben" because its phonology causes the Standard Japanese syllables /(d)zɯ, (d)ʑi/, as well as, intervocally, /tsɯ, tɕi, sɯ, ɕi/ to merge into /zɯ/. There is a negative connotation that surrounds people that speak this dialect, labeling them as lazy country folks. Due to this negativity speakers of Tohoku-ben will hide their accents when speaking standard Japanese.[34]

There are dozens of versions of this Tohoku-ben, with two notably major ones in found in the Aomori Prefecture; Tsugaru-ben (津軽弁) and Nambu-ben (南部弁). The former is prevalent in the area around Hirosaki City, and the latter is heard in and around the city of Hachinohe. According to a study done by Hideki Tanaka, the "dz" and "s" consonants undergo palatalization in the Nambu dialect. There is also the dialect Shimokita-ben (下北弁), which was used in the early Russian–Japanese Dictionary made by a Japanese Russian man whose father came from the Shimokita Peninsula. It is a combination of Tsugaru-ben and Nambu-ben.[35]

Media

The largest newspaper by readership is The Tōō Nippō Press with a daily readership of 245,000, 56% of the total share of the newspaper market in the prefecture.[36]

Notable people from Aomori Prefecture

- Osamu Dazai, author

- Miki Hanada, nurse

- Miki Furukawa, musician, and former bass guitarist and singer for the Japanese rock band Supercar

- Junji Ishiwatari, musician, and former guitarist and songwriter for the Japanese rock band Supercar

- Daimaou Kosaka, comedian

- Kenichi Matsuyama, actor

- Daisuke Matsuzaka, Major League Baseball pitcher[37]

- Hani Motoko, journalist

- Koji Nakamura, musician, and former guitarist and lead singer for the Japanese rock band Supercar

- Yoshie Shiratori, escape artist

- Daigo Umehara, fighting game player, one of the most successful Street Fighter players

- Yoshisada Yonezuka, martial arts instructor

- Yokoyama Yui, Aomori Representative for AKB48 Team 8

Notes

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005). "Aomori-ken" in Japan Encyclopedia, p. 35, p. 35, at Google Books; "Tōhoku" in p. 970, p. 970, at Google Books

- Nussbaum, "Aomori" in p. 35, p. 35, at Google Books

- Takaaki Nihei (2018). The Regional Geography of Japan. Sapporo: The Hokkaido University Press. pp. 13–19. ISBN 978-4-8329-0373-9.

- 自然公園都道府県別面積総括 [General overview of area figures for Natural Parks by prefecture] (PDF) (in Japanese). Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- 青森県内の自然公園 [Natural Parks in Aomori Prefecture] (in Japanese). Aomori Prefecture. 31 March 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- "Aomori (Japan): Prefecture, Cities, Towns and Villages - Population Statistics, Charts and Map". www.citypopulation.de. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- "Historic Site, Odai-Yamamoto Site" (PDF). Jomon Archaeological Sites in Hokkaido and Northern Tohoku. 2019. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "Choshichiyachi Shell Midden". Jomon Archaeological Sites in Hokkaido and Northern Tohoku. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Junko Habu (September 2008). "Growth and decline in complex hunter-gatherer societies: a case study from the Jomon period Sannai Maruyama site, Japan" (PDF). Antiquity. Cambridge University Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2014-12-25. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Junko Habu; Mark Hall (1 December 2013). Climate Change, Human Impacts on the Landscape, and Subsistence Specialization: Historical Ecology and Changes in Jomon Hunter-Gatherer Lifeways. The Archaeology and Historical Ecology of Small Scale Economies. University of California, Berkeley. ISBN 9780813042428. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Kazuro Hanihara (1990). "Emishi, Ezo and Ainu: An Anthropological Perspective". Japan Review. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Mark J. Hudson (1999). "Ainu Ethnogenesis and the Northern Fujiwara". Arctic Anthropology. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "十三湊遺跡" [Ruins of Tosaminato]. The Agency for Cultural Affairs (in Japanese). Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- "History of Hiraizumi". Hiraizumi, Pure Land's World. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Statistics Bureau of Japan

- "地名「三陸地方」の起源に関する地理学的ならびに社会学的問題" [Geographical and sociological issues concerning the origin of the place name "Sanriku region"] (PDF) (in Japanese). 30 June 1994. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 July 2011. Retrieved 30 June 2020.

- Aomori City Homepage - The Story of Aomori. Retrieved on 7 June 2007 Archived May 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- "4 North Korean defectors reach Japan after 6 days on the open sea" Archived 2014-02-02 at the Wayback Machine Japan News Review (3 June 2007). Retrieved on 19 July 2008

- "The area is searched". Earthquake Memorial Museum. Tohoku Regional Bureau, Ministry of Land, Infrastructure, Transport and Tourism. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- Aomori City Homepage - The Story of Aomori. Retrieved on 7 June 2007 Archived May 22, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- 青森県平内町. "水産業 - 青森県平内町". town.hiranai.aomori.jp. Retrieved 28 March 2018.

- "Seiryu-ji Temple: aka: The Big Buddha in Aomori". Aomoristory.blogspot.com. August 1, 2010. Retrieved July 15, 2012.

- "Behold! Christ's grave in Shingo, Aomori Prefecture, The Japan Times". Retrieved 2012-06-06.

- BBC News: "The Japanese Jesus trail" by Duncan Bartlett (9 September 2006) Retrieved 7 September 2010.

- "'Jesus tomb' Aomori tourist draw, The Japan Times". Retrieved 2012-06-06.

- "残したい"日本の音風景100選"パンフレット" ["100 Soundscapes of Japan" pamphlet] (PDF) (in Japanese). Ministry of the Environment. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "UPDATE: U.S. fighter dumps fuel tanks during flight after engine fire". The Asahi Shimbun. Archived from the original on 19 February 2019. Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "Kogin-zashi Embroidery". Retrieved 15 November 2019.

- "Festivals and Fireworks : Aomori Prefecture". Northern-Tohoku. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013.

- "Tachi Neputa Festival in Goshogawara City". Aomorimori.wordpress.com. September 15, 2009. Retrieved July 13, 2012.

- "Fall Festivals : Aomori Prefecture". Northern-Tohoku. Archived from the original on May 14, 2013.

- "Lake Towada Winter Festival". MisawaJapan.com. Retrieved August 6, 2009.

- "出発便:青森空港発" [Departures from Aomori Airport]. Aomori Airport (in Japanese). Retrieved 15 June 2020.

- "All You Need to Know About Japan's Weirdest Dialect, Tohoku-ben". Tofugu. July 25, 2011. Archived from the original on November 7, 2011.

- "Web東奥・天地人20110201" (in Japanese). Toonippo. February 1, 2011. Archived from the original on 20 March 2011. Retrieved March 20, 2011.

- "Company listing". The Tōō Nippō Press. Retrieved 20 May 2020.

- "Matsuzaka". nikkansports.com. Archived from the original on 2008-06-09. Retrieved 2008-05-23.

References

- Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric and Käthe Roth. (2005). Japan encyclopedia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01753-5; OCLC 58053128

- Tanaka, Hideki (1996-09-10). "On the Palatalization of [dz] and [s] in the Nambu Dialect" (PDF). Tsukuba English Studies. 15: 159–186.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aomori prefecture. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Aomori prefecture. |

- Aomori Prefecture Official Website (in Japanese)

- Aomori Prefecture Official Website (in English)