Emishi

The Emishi, Ebisu or Ezo (蝦夷) constituted an ancient ethnic group of people who lived in parts of Honshū, especially in the Tōhoku region which was referred to as michi no oku (道の奥) in contemporary sources. The first mention of them in literature dates to AD 400, in which they are mentioned as "the hairy people" from the Chinese records. Some Emishi tribes resisted the rule of the Japanese Emperors during the late Nara and early Heian periods (7th–10th centuries AD).

Emishi paying homage to Prince Shotoku. Produced in 1324, based on Shotokutaishi e-den e-maki, made in 1069. | |

| Origin | |

|---|---|

| Word/name | Japanese |

| Region of origin | Japan |

| from Namio, Egami, et al., Ainu to kodai Nippon. Japan: Shogakukan, 1982, p. 92. | |

The origin of the Emishi is currently disputed. They are often thought to have descended from some tribes of the Jōmon people. Some historians believe that they were related to the Ainu people, but others disagree with this theory and see them as a distinct ethnicity.[1]

History

The Emishi were represented by different tribes, some of whom became allies of the Japanese (fushu, ifu) and others of whom remained hostile (iteki).[2] The Emishi in northeastern Honshū relied on their horses in warfare. They developed a unique style of warfare in which horse archery and hit-and-run tactics proved very effective against the slower contemporary Japanese imperial army that mostly relied on heavy infantry. Their livelihood was based on hunting and gathering as well as on the cultivation of grains such as millet and barley. Recently, it has been thought that they practiced rice cultivation in areas where rice could be easily grown. The first major attempts to subjugate the Emishi in the 8th century were largely unsuccessful. The imperial armies, which were modeled after the mainland Chinese armies, were no match for the guerrilla tactics of the Emishi.[3]

It was the development of horse archery and the adoption of Emishi tactics by the early Japanese warriors that led to the Emishi defeat. The success of the gradual change in battle tactics came at the very end of the 8th century in the 790s under the command of the general Sakanoue no Tamuramaro.[4] They either submitted themselves to imperial authority as fushu and ifu or migrated further north, some to Hokkaidō. By the mid-9th century, most of their land in Honshū was conquered, and they ceased to be independent. However, they continued to be influential in local politics as subjugated, though powerful, Emishi families created semi-autonomous feudal domains in the north. In the two centuries following the conquest, a few of these domains became regional states that came into conflict with the central government.

They are described in the Nihon Shoki in the following way:

Amongst these Eastern savages the Yemishi are the most powerful; their men and women live together promiscuously; there is no distinction of father and child. In winter, they dwell in holes; in summer, they live in nests. Their clothing consists of furs, and they drink blood. Brothers are suspicious of one another. In ascending mountains, they are like flying birds; in going through the grass, they are like fleet quadrupeds. When they receive a favour, they forget it, but if an injury is done them they never fail to revenge it. Therefore, they keep arrows in their top-knots and carry swords within their clothing. Sometimes, they draw together their fellows and make inroads on the frontier. At other times, they take the opportunity of the harvest to plunder the people. If attacked, they conceal themselves in the herbage; if pursued, they flee into the mountains. Therefore, ever since antiquity, they have not been steeped in the kingly civilizing influences.[5]

Etymology

The record of Emperor Jimmu in the Nihon Shoki mentions the "Emishi" (愛瀰詩 in ateji) whom his armed forces defeated before he was enthroned as the Emperor of Japan.[6] According to Nihon Shoki, Takenouchi no Sukune in the era of Emperor Keikō proposed that they should subjugate Emishi (蝦夷) of Hitakami no Kuni (日高見国) in eastern Japan[1][6]. The first mention of Emishi from a source outside Japan was in the Chinese Book of Song in 478 which referred to them as "hairy people" (毛人). The book refers to "the 55 kingdoms (国) of the hairy people (毛人) of the East" as a report by King Bu—one of the Five kings of Wa.

Most likely by the 7th century AD, the Japanese used this kanji to describe these people, but changed the reading from kebito or mōjin to Emishi. Furthermore, during the same century, the kanji character was changed to 蝦夷, which is composed of the kanji for "shrimp" and for "barbarian". This is thought to refer to the long whiskers of a shrimp; however, this is not certain. The barbarian aspect clearly described an outsider, living beyond the border of the emerging empire of Japan, which saw itself as a civilizing influence; thus, the empire was able to justify its conquest. This kanji was first seen in the T'ang sources that describe the meeting with the two Emishi that the Japanese envoy brought with him to China (see below). The kanji character may have been adopted from China, but the reading "Ebisu" and "Emishi" were Japanese in origin and most likely came from either the Japanese "yumishi" which means bowman (their main weapon) or "emushi" which is sword in the Ainu tongue.[7]

Other origins—such as the word enchiu for "man" in the Ainu tongue—have been proposed. However, the way it sounds is almost phonetically identical to emushi so it may most likely have had an Ainoid origin. "Ainoid" distinguishes the people who are related to, or who are ancestors of, the Ainu, who first emerge as "Ezo" in Hokkaido in the Kamakura period and then become known as Ainu in the modern period.

Battles with Yamato army

The Nihon Shoki's entry for Emperor Yūryaku, also known as Ohatsuse no Wakatakeru, records an uprising, after the Emperor's death, of Emishi troops who had been levied to support an expedition to Korea. Emperor Yūryaku is suspected to be King Bu, but the date and the existence of Yūryaku are uncertain, and the Korean reference may be anachronistic. However, the compilers clearly felt that the reference to Emishi troops was credible in this context.

In 658, Abe no Hirafu's naval expedition of 180 ships reaches Aguta (present day Akita) and Watarishima (Hokkaidō). An alliance with Aguta Emishi, Tsugaru Emishi and Watarishima Emishi was formed by Abe who then stormed and defeated a settlement of the Mishihase (Su-shen in the Aston translation of the Nihongi), a people of unknown origin. This is one of the earliest reliable records of the Emishi people extant. The Mishihase may have been another ethnic group who competed with the ancestors of the Ainu for Hokkaidō. The expedition happens to be the furthest northern penetration of the Japanese Imperial army until the 16th century, and that later settlement was from a local Japanese warlord who was independent of any central control.[8][9]

In 709, the fort of Ideha was created close to present day Akita. This was a bold move since the intervening territory between Akita and the northwestern countries of Japan was not under government control. The Emishi of Akita in alliance with Michinoku attacked Japanese settlements in response. Saeki no Iwayu was appointed Sei Echigo Emishi shōgun. He used 100 ships from the Japan sea side countries along with soldiers recruited from the eastern countries and defeated the Echigo (present day Akita) Emishi.[10]

In 724, Taga Fort was built by Ōno no Omi Azumahito near present-day Sendai and became the largest administrative fort in the northeast region of Michinoku. As Chinju shōgun he steadily built forts across the Sendai plain and into the interior mountains in what is now Yamagata Prefecture. Guerilla warfare was practiced by the horse riding Emishi who kept up pressure on these forts, but Emishi allies ifu and fushu were also recruited and promoted by the Japanese to fight against their kinsmen.

In 758, after a long period of stalemate, the Japanese army under Fujiwara no Asakari penetrated into what is now northern Miyagi Prefecture, and established Momonofu Castle on the Kitakami River. The fort was built despite constant attacks by the Emishi of Isawa (present-day southern Iwate prefecture).

Thirty-Eight Years' War

773 AD marked the beginning of the Thirty-Eight Years' War (三十八年戦争) with the defection of Korehari no Azamaro, a high-ranking Emishi officer of the Japanese army based in Taga Castle. The Emishi counterattacked along a broad front starting with Momonohu Castle, destroying the garrison there before going on to destroy a number of forts along a defensive line from east to west established painstakingly over the past generation. Even Taga Castle was not spared. Large Japanese forces were recruited, numbering in the thousands, the largest forces perhaps ten to twenty thousand strong fighting against an Emishi force that numbered at most around three thousand warriors, and at any one place around a thousand. In 776 a huge army of over 20,000 men was sent to attack the Shiwa Emishi, but failed to destroy the enemy who then successfully counterattacked their cumbersome foes in the Ōu Mountains. In 780 the Emishi attacked the Sendai plain, torching Japanese villages there. The Japanese were in a near panic as they tried to tax and recruit more soldiers from the Bandō.[11]

In the 789 AD Battle of Koromo River (also known as Battle of Sufuse) the Japanese army under Ki no Kosami Seito shōgun was defeated by the Isawa Emishi under their general Aterui. A four thousand-strong army was attacked as they tried to cross the Kitakami River by a force of a thousand Emishi. The imperial army suffered its most stunning defeat, losing a thousand men, many of whom drowned.

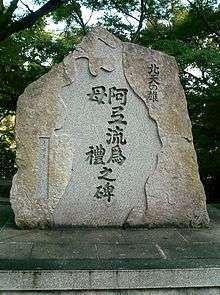

In 794, many key Shiwa Emishi including Isawa no kimi Anushiko of what is now northern Miyagi Prefecture became allies of the Japanese. This was a stunning reversal to the aspirations of those Emishi who still fought against the Japanese. The Shiwa Emishi were a very powerful group and were able to attack smaller Emishi groups successfully as their leaders were promoted into imperial rank. This had the effect of isolating one of the most powerful and independent Emishi, the Isawa confederation. The newly appointed shōgun general, Sakanoue no Tamuramaro, then attacked the Isawa Emishi, relentlessly using soldiers trained in horse archery. The result was a desultory campaign that eventually led to Aterui's surrender in 802. The war was mostly over and many Emishi groups submitted themselves to the imperial government. However, skirmishes still took place and it was not until 811 that the so-called Thirty-Eight Years' War was over.[12] North of the Kitakami River, the Emishi were still independent, but the large scale threat that they posed ceased with the defeat of the Isawa Emishi in 802.

Abe clan, Kiyohara clan and Northern Fujiwara

After their conquest, some Emishi leaders became part of the regional framework of government in the Tōhoku culminating with the Northern Fujiwara regime. This regime and others such as the Abe and Kiyohara were created by local Japanese gōzoku and became regional semi-independent states based on the Emishi and Japanese people. However, even before these emerged, the Emishi people progressively lost their distinct culture and ethnicity as they became minorities.

The Northern Fujiwara were thought to have been Emishi, but there is some doubt as to the lineage of them, and if they were descended from local Japanese families who resided in the Tōhoku (unrelated to the Fujiwara of Kyoto) then the study would confirm this. Both the Abe and Kiyohara families were almost certainly of Japanese descent, both of whom represented gōzoku, powerful families who had moved into the provinces of Mutsu and Dewa perhaps during the ninth century though when they emigrated is not known for certain. They were likely a Japanese frontier family who developed regional ties with the descendants of the Emishi fushu, and may have been seen as fushu themselves since they had lived in the region for several generations.

Soon after World War II, mummies of the Northern Fujiwara family in Hiraizumi (the capital city of the Northern Fujiwara), hence thought to have been related to the Ainu, were studied by scientists. However, the researchers concluded that the rulers of Hiraizumi were not related to the ethnic Ainu but more similar to contemporary Japanese of Honshū.[13] This was seen as evidence that the Emishi were not related to the Ainu. This had the effect of popularizing the idea that the Emishi were like other contemporary ethnic Japanese who lived in northeast Japan, outside of Yamato rule.

Minamoto no Yoritomo, a descendant of Emperor Seiwa, finally defeated the Northern Fujiwara in 1189 and established the Kamakura shogunate in 1192.

Ethnic relations

Emishi–Ainu theory

This theory suggests that Emishi are related to the Ainu. This theory is controversial as many Emishi tribes were known as excellent horse archers and warriors. Although the Ainu are also known as archers, they did not use horses and their war-style was clearly different. They also differed in cultural terms.[1][14]

Other theories

There is a theory that the Emishi spoke the "Zūzū dialect" (the ancestor of Tōhoku dialect) and are a different ethnic group from the Ainu and early Yamato.[15] Especially from the similarity of Tōhoku dialect and Izumo dialect, it is suggested that some of the Izumo people, who did not obey Yamato royalty after the delegation of governance, escaped to the Tōhoku region and became the Emishi.[16][17]

Relationship to the Jōmon and Ainu

Recent scholarship has created a much more complicated portrait of this people.

The Emishi appear to have been united by a common Jōmon-era derived language, albeit of unknown origin and linguistic relation. Some link the Jōmon-language(s) to the Ainu language but this view is controversial.

In the study of Jōmon skeletal remains dating from thousands of years ago, a direct connection with the Emishi (and Ainu) was confirmed, showing a definite linkage between the two groups. This linkage however, shows that the Jōmon people were very different from both modern Japanese and other modern East Asians. The physical appearance of a number of the Ainu who were first encountered by the Europeans in the 19th century were similar to Caucasians, and thus caused quite a stir among contemporary academics, and has spurred debate about their origins. It is thus surmised that the Jōmon also were physically unlike other East Asians. That said, physical anthropologists have found that diachronically, and geographically, the skeletal structure of the Jōmon population changed over time from southwest to northeast, paralleling the actual migration of Japanese speakers historically, so that more Jōmon traits are preserved in the north. It is known today that the Jōmon people were not a homogeneous group but a mixture of two or more distinct populations that lived in Japan before and during the Jōmon period.[18]

Studies of skeletal remains from larger settlements in the Tōhoku –corresponding to places where burial mounds (kofun) were built – suggest that the Emishi had physical traits that were midway between Jōmon and other Japanese. Hence the Emishi may have descended from both a Jōmon-like population and so-called "kofun people", who were not a distinct or genetic/ethnic group, but a mixture of both Jōmon and the more recent groups identified with the Yayoi culture. This dovetails with the so-called "transformation theory", that native Jōmon peoples changed gradually with the infusion of Yayoi immigrants into the Tōhoku, rather than the "replacement theory", which posits that the Jōmon were entirely replaced by Yayoi.[19]

These two populations were not distinguished by contemporaries, but rather by present-day physical anthropologists. Historically, they were seen as one group by contemporaries, mainly those who were descendants of the natives (the Jōmon) called Emishi and Ebisu who also had in their population those of mixed ethnicity, most likely descendants of early Japanese colonists. In addition, the contemporary Japanese for their part looked upon the Emishi as foreigners and barbarians whose lands they desired to conquer and incorporate into the Japanese state.

Though it is not known how much the Emishi population changed as Japanese settlers and frontiersmen began to live in their territories even before the conquest, the existence of Emishi Kofun types attests to some form of ethnic mixing. The Japanese established trading relations with the Emishi by which their horses were imported and iron tools and weapons exported to their territories. To complicate matters, some ethnic Japanese allied themselves with the Emishi in their wars against the Yamato court. The latter were known in the Nihon Shoki as "Japanese captives" of the Emishi.

The people who migrated to the northern tip of Honshū and Hokkaidō region retained their identity and their separate ethnicity, and their descendants eventually formed the Satsumon culture in Hokkaidō. Historically, they became a distinctly different population from those who were conquered and integrated into the Japanese state.

Genetics

_worldwide.png)

The Emishi appear to be directly related to the local population during the Jōmon period. In contrast to the Ainu, the Emishi samples largely belonged to paternal Haplogroup C-M8 (C1a1), which is one of the two major Jōmon markers and only found in Japan. The next relative marker, C1a2, was commonly found in Paleolithic and Neolithic Europeans and today in some Europeans, Armenians and Berber people. About 10% of modern Japanese belong to C1a1. This is seen as evidence for their direct relation to one of the Jōmon people and their ethnic distinction from the Ainu people, who mostly belong to haplogroup D1b.[21]

Envoys to the Tang court

The evidence that the Emishi were also related to the Ainu comes from historical documents. One of the best sources of information comes from both inside and outside Japan, from contemporary Tang- and Song-dynasty histories as these describe dealings with Japan, and from the Shoku Nihongi. For example, there is a record of the arrival of the Japanese foreign minister in AD 659 in which conversation is recorded with the Tang Emperor. In this conversation we have perhaps the most accurate picture of the Emishi recorded for that time period. This episode is repeated in the Shoku Nihongi in the following manner:

Two Emishi, a man and woman, from contemporary Tōhoku accompanied the minister Sakaibe no Muraji to Tang China. The emperor was delighted with the two Emishi because of their "strange" physical appearance. This emperor was most likely the Emperor Tang Taizong who was familiar with many ethnic groups throughout his Empire, from Uyghurs and Turks to Middle Eastern traders. The Japanese envoy for his part describes the contemporary relationship with the various Emishi: those who had allied themselves with the Yamato court (known as 和蝦夷 niki-emishi, i.e. "gentle Emishi"), those who remained as enemies staunchly opposed to Yamato (known as 荒蝦夷 ara-emishi, i.e. "rough Emishi" or "wild Emishi"), and the distant Tsugaru Emishi (located in present-day northern Aomori and in southern Hokkaidō). All Chinese documents from the Tang and Song refer to them as having a separate state north of Japan and call them 毛人 (Mandarin máo rén, Sino-Japanese mōjin, "hairy people"). This is also corroborated in the Shoku Nihongi, in which they are described consistently as having long beards and as kebito, or "hairy people", characteristics that have been used to describe the Ainu in the modern period. These same kanji characters were read as "emishi" before the Nara period.

In popular culture

- The term Emishi is used for the village tribe of the main character Ashitaka in the Hayao Miyazaki animated film Princess Mononoke. The village was a last pocket of Emishi surviving into the Muromachi period (16th century).[22]

Notes

- Aston, W.G., trans. Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to AD 697. Tokyo: Charles E.Tuttle Co., 1972 (reprint of two volume 1924 edition), VII 18. Takahashi, Tomio. "Hitakami." In Egami, Namio ed. Ainu to Kodai Nippon. Tokyo: Shogakukan, 1982.

- Takahashi, pp. 110–113.

- Farris, William Wayne, Heavenly Warriors (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992), p. 117.

- Farris, pp. 94–95, 108–113.

- Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from the Earliest Times to A.D. 697, Volume 1.

- 朝廷軍の侵略に抵抗 (in Japanese). Iwate Nippo. September 24, 2004. Archived from the original on March 3, 2016. Retrieved March 1, 2011.

- Takahashi, Takashi, 蝦夷 (Emishi) (Tokyo: Chuo koron, 1986), pp.22–27. Good discussion on the possible origins of the name.

- Aston, W. G. trans. Nihongi (Tokyo: Charles E. Tuttle), pp. 252, 260, 264.

- Nakanishi, Susumu, エミシとは何か (Emishi to wa nanika), (Tokyo:Kadokawa shoten,1993), pp. 134–140. Modern analysis of the expedition.

- Farris, p.86. Farris's account does not have all the details, but is a readily available source for the war's chronology in English.

- Farris, pp. 90–96.

- Takahashi, pp. 168–196. Very detailed analysis of the end of the war and the effects on the former Emishi territory.

- Farris, p.83.

- Hubbard, Ben (2016-12-15). Samurai Warriors. Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC. ISBN 9781502624598.

- 小泉保(1998)『縄文語の発見』青土社 (in Japanese)

- 高橋克彦(2013)『東北・蝦夷の魂』現代書館 (in Japanese)

- 『古代に真実を求めて 第七集(古田史学論集)』2004年、古田史学の会(編集) (in Japanese)

- 上田正昭他『日本古代史の謎再考(エコール・ド・ロイヤル 古代日本を考える1)』 学生社 1983年 pp.52より

- Ossenberg, Nancy (see reference) has the best evidence of this relationship with the Jōmon. Also, a newer study, Ossenberg, et al., "Ethnogenesis and craniofacial change in Japan from the perspective of nonmetric traits" (Anthropological Science v.114:99-115) is an updated analysis published in 2006 which confirms this finding.

- 崎谷満『DNA・考古・言語の学際研究が示す新・日本列島史』(勉誠出版 2009年)(in Japanese)

- 崎谷満『DNA・考古・言語の学際研究が示す新・日本列島史』(勉誠出版 2009年)(in Japanese)

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/311680710_Japanese_Mythology_in_Film_A_Semiotic_Approach_to_Reading_Japanese_Film_and_Anime_Paperback

References

- Aston, W. G. Nihongi: Chronicles of Japan from Earliest Times to A.D. 697. London: Kegan Paul, 1924. Originally published in 1896. The standard English translation of the ancient Japanese compilation known as the Shoku Nihongi.

- Farris, William Wayne. Heavenly Warriors: The Evolution of Japan's Military: 500–1300. Harvard: Harvard University Press, 1996. ISBN 978-0-674-38703-4, ISBN 978-0-674-38704-1.

- Nagaoka, Osamu. 古代東国物語 (Kodai Tōgoku Monogatari). Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 1986. For readers of Japanese, a detailed account of the campaign against Aterui. ISBN 978-4-04-703170-8.

- Nakanishi, Susumu. エミシとは何か: 古代東アジアと北方日本 (Emishi to wa nani ka: kodai higashiajia to hoppō nihon). Tokyo: Kadokawa Shoten, 1993. Japanese source that conducted a study of the skeletal remains of persons who lived in the Tōhoku region both during the Jōmon and Yayoi periods. Limited coverage of skeletal remains of the historical period, but covers the history. ISBN 978-4-04-703247-7.

- Ossenberg, Nancy S., "Isolate Conservatism and Hybridization in the Population History of Japan" in Akazawa, T. and C. M. Aikens, eds., Prehistoric Hunter Gatherers in Japan: New Research Methods. Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press, 1986. ISBN 978-0-86008-395-5.

- Takahashi, Takashi. 蝦夷: 古代東北人の歴史 (Emishi: kodai Tōhokujin no rekishi). Tokyo: Chūō Kōronsha, 1986. ISBN 978-4-12-100804-6.