Alice's Adventures in Wonderland

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (commonly shortened to Alice in Wonderland) is an 1865 novel written by English author Lewis Carroll (the pseudonym of Charles Dodgson).[1] It tells of a young girl named Alice, who falls through a rabbit hole into a subterranean fantasy world populated by peculiar, anthropomorphic creatures. It is considered to be one of the best examples of the literary nonsense genre.[2][3] The tale plays with logic, giving the story lasting popularity with adults as well as with children.[2]

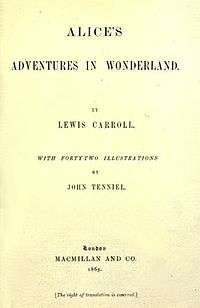

.jpg) Cover of the original edition (1865) | |

| Author | Lewis Carroll |

|---|---|

| Illustrator | John Tenniel |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Genre | Fantasy Literary nonsense |

| Publisher | Macmillan |

Publication date | 26 November 1865 |

| Followed by | Through the Looking-Glass |

One of the best-known and most popular works of English-language fiction, its narrative, structure, characters, and imagery have been enormously influential in popular culture and literature, especially in the fantasy genre.[3] The work has never been out of print, and it has been translated into at least 97 languages.[4] Its ongoing legacy encompasses many adaptations for stage, screen, radio, art, theme parks, board games, and video games.[5] Carroll published a sequel in 1871, entitled Through the Looking-Glass, and a version for young children, The Nursery "Alice", in 1890.

Background

"All in the golden afternoon..."

Alice's Adventures in Wonderland was published in 1865, three years after Lewis Carroll and the Reverend Robinson Duckworth, on 4 July,[6] rowed up the Isis river in a boat with three young girls—a day known as the "golden afternoon,"[7] prefaced in the novel as a poem. The poem might be a confusion or even another Alice-tale, for it turns out that particular day was cool, cloudy and rainy.[8] The three girls would be the daughters of scholar Henry Liddell: Lorina Charlotte Liddell (aged 13; "Prima" in the book's prefatory verse); Alice Pleasance Liddell (aged 10; "Secunda" in the verse); and Edith Mary Liddell (aged 8; "Tertia" in the verse).[9]

The journey began at Folly Bridge, Oxford and ended five miles away in the Oxfordshire village of Godstow. During the trip Dodgson told the girls a story that featured a bored little girl named Alice who goes looking for an adventure. The girls loved it, and Alice Liddell asked Dodgson to write it down for her.[10]

Manuscript: Alice's Adventures Under Ground

He would begin writing the manuscript of the story the next day, although that earliest version is lost to history. The girls and Dodgson took another boat trip a month later when he elaborated the plot to the story of Alice, and in November he began working on the manuscript in earnest.[11]

To add the finishing touches he would research natural history for the animals presented in the book, and then had the book examined by other children—particularly those of George MacDonald. Though Dodgson did add his own illustrations, he would approach John Tenniel to illustrate the book for publication, telling him that the story had been well liked by children.[11]

On 26 November 1864, Dodgson gave Alice the handwritten manuscript of Alice's Adventures Under Ground, with illustrations by Dodgson himself, dedicating it as "A Christmas Gift to a Dear Child in Memory of a Summer's Day".[12] Some, including Martin Gardner, speculate that there was an earlier version that was destroyed later by Dodgson when he wrote a more elaborate copy by hand.[13]

Before Alice received her copy, Dodgson was already preparing it for publication and expanding the 15,500-word original to 27,500 words,[14] most notably adding the episodes about the Cheshire Cat and the Mad Tea Party.

Synopsis

Chapter One – Down the Rabbit Hole: Alice, a seven-year-old girl, is feeling bored and drowsy while sitting on the riverbank with her elder sister. She notices a talking, clothed white rabbit with a pocket watch run past. She follows it down a rabbit hole where she suddenly falls a long way to a curious hall with many locked doors of all sizes. She finds a little key to a door too small for her to fit through, but through it, she sees an attractive garden. She then discovers a bottle on a table labelled "DRINK ME," the contents of which cause her to shrink too small to reach the key which she had left on the table. She subsequently eats a cake labelled "EAT ME" in currants as the chapter closes.

Chapter Two – The Pool of Tears: The chapter opens with Alice growing to such a tremendous size that her head hits the ceiling. Unhappy, Alice begins to cry and her tears literally flood the hallway. Shrinking down again due to a fan she had picked up, Alice swims through her own tears and meets a mouse, who is swimming as well. Alice, thinking he may be a French mouse, tries to make small talk with him in elementary French. Her opening gambit "Où est ma chatte?" (transl. "Where is my cat?"), however, offends the mouse, who then tries to escape her.

Chapter Three – The Caucus Race and a Long Tale: The sea of tears becomes crowded with other animals and birds that have been swept away by the rising waters. Alice and the other animals convene on the bank and the question among them is how to get dry again. Mouse gives them a very dry lecture on William the Conqueror. A dodo decides that the best thing to dry them off would be a Caucus-Race, which consists of everyone running in a circle with no clear winner. Alice eventually frightens all the animals away, unwittingly, by talking about her (moderately ferocious) cat.

Chapter Four – The Rabbit Sends a Little Bill: White Rabbit appears again in search of the Duchess's gloves and fan. Mistaking her for his maidservant, Mary Ann, Rabbit orders Alice to go into the house and retrieve them. Inside the house she finds another little bottle and drinks from it, immediately beginning to grow again. The horrified Rabbit orders his gardener, Bill the Lizard, to climb on the roof and go down the chimney. Outside, Alice hears the voices of animals that have gathered to gawk at her giant arm. The crowd hurls pebbles at her, which turn into little cakes. Alice eats them, and they reduce her again in size.

Chapter Five – Advice from a Caterpillar: Alice comes upon a mushroom and sitting on it is a blue caterpillar smoking a hookah. Caterpillar questions Alice, who begins to admit to her current identity crisis, compounded by her inability to remember a poem. Before crawling away, the caterpillar tells Alice that one side of the mushroom will make her taller and the other side will make her shorter. She breaks off two pieces from the mushroom. One side makes her shrink smaller than ever, while another causes her neck to grow high into the trees, where a pigeon mistakes her for a serpent. With some effort, Alice brings herself back to her normal height. She stumbles upon a small estate and uses the mushroom to reach a more appropriate height.

Chapter Six – Pig and Pepper: A fish-footman has an invitation for the Duchess of the house, which he delivers to a frog-footman. Alice observes this transaction and, after a perplexing conversation with the frog, lets herself into the house. The Duchess's cook is throwing dishes and making a soup that has too much pepper, which causes Alice, the Duchess, and her baby (but not the cook or grinning Cheshire Cat) to sneeze violently. Alice is given the baby by the Duchess and, to Alice's surprise, the baby turns into a pig. The Cheshire Cat appears in a tree, directing her to the March Hare's house. He disappears but his grin remains behind to float on its own in the air prompting Alice to remark that she has often seen a cat without a grin but never a grin without a cat.

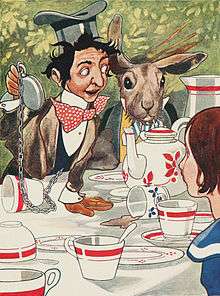

Chapter Seven – A Mad Tea-Party: Alice becomes a guest at a "mad" tea party along with the March Hare, the Hatter, and a very tired Dormouse, who falls asleep frequently only to be violently awakened moments later by the March Hare and the Hatter. The characters give Alice many riddles and stories, including the famous "why is a raven like a writing desk?." The Hatter reveals that they have tea all day because Time has punished him by eternally standing still at 6 PM (tea time). Alice becomes insulted and tired of being bombarded with riddles and she leaves claiming that it was the stupidest tea party that she had ever been to.

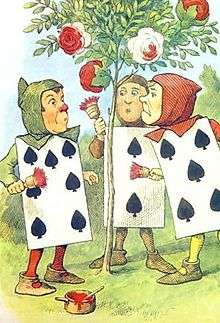

Chapter Eight – The Queen's Croquet Ground: Alice leaves the tea party and enters the garden where she comes upon three living playing cards painting the white roses on a rose tree red because The Queen of Hearts hates white roses. A procession of more cards, kings and queens and even the White Rabbit enters the garden. Alice then meets the King and Queen. The Queen, a figure difficult to please, introduces her signature phrase "Off with his head!" which she utters at the slightest dissatisfaction with a subject. Alice is invited (or some might say ordered) to play a game of croquet with the Queen and the rest of her subjects but the game quickly descends into chaos. Live flamingos are used as mallets and hedgehogs as balls and Alice once again meets the Cheshire Cat. The Queen of Hearts then orders the Cat to be beheaded, only to have her executioner complain that this is impossible since the head is all that can be seen of him. Because the cat belongs to the Duchess, the Queen is prompted to release the Duchess from prison to resolve the matter.

Chapter Nine – The Mock Turtle's Story: The Duchess is brought to the croquet ground at Alice's request. She ruminates on finding morals in everything around her. The Queen of Hearts dismisses her on the threat of execution and she introduces Alice to the Gryphon, who takes her to the Mock Turtle. The Mock Turtle is very sad, even though he has no sorrow. He tries to tell his story about how he used to be a real turtle in school, which the Gryphon interrupts so they can play a game.

Chapter Ten – Lobster Quadrille: The Mock Turtle and the Gryphon dance to the Lobster Quadrille, while Alice recites (rather incorrectly) "'Tis the Voice of the Lobster". The Mock Turtle sings them "Beautiful Soup" during which the Gryphon drags Alice away for an impending trial.

Chapter Eleven – Who Stole the Tarts?: Alice attends a trial whereby the Knave of Hearts is accused of stealing the Queen's tarts. The jury is composed of various animals, including Bill the Lizard, the White Rabbit is the court's trumpeter, and the judge is the King of Hearts. During the proceedings, Alice finds that she is steadily growing larger. The dormouse scolds Alice and tells her she has no right to grow at such a rapid pace and take up all the air. Alice scoffs and calls the dormouse's accusation ridiculous because everyone grows and she cannot help it. Meanwhile, witnesses at the trial include the Hatter, who displeases and frustrates the King through his indirect answers to the questioning, and the Duchess's cook.

Chapter Twelve – Alice's Evidence: Alice is then called up as a witness. She accidentally knocks over the jury box with the animals inside them and the King orders the animals be placed back into their seats before the trial continues. The King and Queen order Alice to be gone, citing Rule 42 ("All persons more than a mile high to leave the court"), but Alice disputes their judgement and refuses to leave. She argues with the King and Queen of Hearts over the ridiculous proceedings, eventually refusing to hold her tongue, only to say, "It's not that I was the one who stole the tarts in the first place", in the process. Finally, the Queen confirms that Alice was the culprit responsible of stealing the tarts after all (which automatically pardons the Knave of Hearts of his charges), and shouts, "Off with her head!", but Alice is unafraid, calling them just a pack of cards; although Alice holds her own for a time, the card guards soon gang up and start to swarm all over her. Alice's sister wakes her up from a dream, brushing what turns out to be some leaves and not a shower of playing cards from Alice's face. Alice leaves her sister on the bank to imagine all the curious happenings for herself.

Characters

The main characters in Alice's Adventures in Wonderland are the following:

- Alice

- The White Rabbit

- The Mouse

- The Dodo

- The Lory

- The Eaglet

- The Duck

- Pat

- Bill the Lizard

- Puppy

- The Caterpillar

- The Duchess

- The Cheshire Cat

- The Mad Hatter

- The March Hare

- The Dormouse

- The Queen of Hearts

- The King of Hearts

- The Knave of Hearts

- The Gryphon

- The Mock Turtle

Character allusions

In The Annotated Alice, Martin Gardner provides background information for the characters. The members of the boating party that first heard Carroll's tale show up in Chapter 3 ("A Caucus-Race and a Long Tale"). Alice Liddell herself is there, while Carroll is caricatured as the Dodo (because Dodgson stuttered when he spoke, he sometimes pronounced his last name as Dodo-Dodgson). The Duck refers to Canon Duckworth, and the Lory and Eaglet to Alice Liddell's sisters Lorina and Edith.[13]:27

Bill the Lizard may be a play on the name of British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli.[15] One of Tenniel's illustrations in Through the Looking-Glass—the 1871 sequel to Alice—depicts the character referred to as the "Man in White Paper" (whom Alice meets as a fellow passenger riding on the train with her) as a caricature of Disraeli, wearing a paper hat.[13]:172 The illustrations of the Lion and the Unicorn (also in Looking-Glass) bear a striking resemblance to Tenniel's Punch illustrations of Gladstone and Disraeli as well.[13]:226

Gardner has suggested that the Hatter is a reference to Theophilus Carter, a furniture dealer known in Oxford, and that Tenniel apparently drew the Hatter to resemble Carter, on a suggestion of Carroll's.[13]:69 The Dormouse tells a story about three little sisters named Elsie, Lacie, and Tillie. These are the Liddell sisters: Elsie is L.C. (Lorina Charlotte); Tillie is Edith (her family nickname is Matilda); and Lacie is an anagram of Alice.[13]:75

The Mock Turtle speaks of a drawling-master, "an old conger eel," who came once a week to teach "Drawling, Stretching, and Fainting in Coils." This is a reference to the art critic John Ruskin, who came once a week to the Liddell house to teach the children drawing, sketching, and painting in oils. (The children did, in fact, learn well; Alice Liddell, for one, produced a number of skilful watercolours.)[13]:98

The Mock Turtle also sings "Turtle Soup." This is a parody of a song called "Star of the Evening, Beautiful Star", which was performed as a trio by Lorina, Alice and Edith Liddell for Lewis Carroll in the Liddell home during the same summer in which he first told the story of Alice's Adventures Under Ground.[16]

Poems and songs

Carroll wrote multiple poems and songs for Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, including:

- "All in the golden afternoon..."—the prefatory verse to the book, an original poem by Carroll that recalls the rowing expedition on which he first told the story of Alice's adventures underground

- "How Doth the Little Crocodile"—a parody of Isaac Watts' nursery rhyme, "Against Idleness and Mischief"

- "The Mouse's Tale"—an example of concrete poetry

- "You Are Old, Father William"—a parody of Robert Southey's "The Old Man's Comforts and How He Gained Them"

- The Duchess's lullaby, "Speak roughly to your little boy..."—a parody of David Bates' "Speak Gently"

- "Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Bat"—a parody of Jane Taylor's "Twinkle Twinkle Little Star"

- "The Lobster Quadrille"—a parody of Mary Botham Howitt's "The Spider and the Fly"

- "'Tis the Voice of the Lobster"—a parody of Isaac Watts' "The Sluggard"

- "Beautiful Soup"—a parody of James M. Sayles's "Star of the Evening, Beautiful Star"

- "The Queen of Hearts"—an actual nursery rhyme

- "They told me you had been to her..."—White Rabbit's evidence

Writing style and themes

Symbolism

Martin Gardner, along with other scholars, have shown the book to be filled with many parodies of Victorian popular culture, suggesting it belongs in spirit with W. S. Gilbert and Alfred Cellier's Topsyturveydom.[17]

Most of the book's adventures may have been based on/influenced by people, situations, and buildings in Oxford and at Christ Church. For example, the "Rabbit Hole" symbolised the actual stairs in the back of the Christ Church's main hall. A carving of a griffon and rabbit, as seen in Ripon Cathedral, where Carroll's father was a canon, may have provided inspiration for the tale.[18]

In the eighth chapter, three cards are painting the roses on a rose tree red, because they had accidentally planted a white-rose tree that The Queen of Hearts hates. Red roses symbolised the English House of Lancaster, while white roses symbolised their rival House of York, thus the wars between them were the Wars of the Roses.[19]

While the book has remained in print and continually inspires new adaptations, the cultural material from which it draws has become largely specialized knowledge. Dr Leon Coward asserts the book 'suffers' from "readings which reflect today's fascination with postmodernism and psychology, rather than delving into an historically informed interpretation," and speculates that this has been partly driven by audiences encountering the narrative through a 'second-hand' source, explaining "our impressions of the original text are based on a multiplicity of reinterpretations. We don't necessarily realise we're missing anything in understanding the original product, because we're usually never dealing with the original product."[17]

Language

It has been suggested by several people, including Martin Gardner and Selwyn Goodacre,[20] that Dodgson had an interest in the French language, choosing to make references and puns about it in the story. It is most likely that these are references to French lessons—a common feature of a Victorian middle-class girl's upbringing. For example, in the second chapter Alice posits that the mouse may be French. She therefore chooses to speak the first sentence of her French lesson-book to it: "Où est ma chatte?" ("Where is my cat?"). In Henri Bué's French translation, Alice posits that the mouse may be Italian and speaks Italian to it.

Pat's "Digging for apples" could be a cross-language pun, as pomme de terre (literally; "apple of the earth") means potato and pomme means apple.[21]

In the second chapter, Alice initially addresses the mouse as "O Mouse", based on her memory of the noun declensions "in her brother's Latin Grammar, 'A mouse – of a mouse – to a mouse – a mouse – O mouse!'" These words correspond to the first five of Latin's six cases, in a traditional order established by medieval grammarians: mus (nominative), muris (genitive), muri (dative), murem (accusative), (O) mus (vocative). The sixth case, mure (ablative) is absent from Alice's recitation.

Mathematics

As Carroll was a mathematician at Christ Church, it has been suggested that there are many references and mathematical concepts in both this story and Through the Looking-Glass.[20][22] Literary scholar Melanie Bayley asserted in the magazine New Scientist that Dodgson wrote Alice in Wonderland in its final form as a scathing satire on new modern mathematics that were emerging in the mid-19th century.[23]

Examples of references to mathematics in Alice include:

- Chapter 1 ("Down the Rabbit-Hole"): in the midst of shrinking, Alice waxes philosophic concerning what final size she will end up as, perhaps "going out altogether, like a candle"; this pondering reflects the concept of a limit.

- Chapter 2 ("The Pool of Tears"): Alice tries to perform multiplication but produces some odd results: "Let me see: four times five is twelve, and four times six is thirteen, and four times seven is—oh dear! I shall never get to twenty at that rate!" This explores the representation of numbers using different bases and positional numeral systems: 4 × 5 = 12 in base 18 notation, 4 × 6 = 13 in base 21 notation, and 4 × 7 could be 14 in base 24 notation. Continuing this sequence, going up three bases each time, the result will continue to be less than 20 in the corresponding base notation. (After 4 × 12 = 19 in Base 39, the product would be 4 × 13 = 1A in Base 42, then 1B, 1C, 1D, and so on.)

- Chapter 7 ("A Mad Tea-Party"): The March Hare, the Hatter, and the Dormouse give several examples in which the semantic value of a sentence A is not the same value of the converse of A (for example, "Why, you might just as well say that 'I see what I eat' is the same thing as 'I eat what I see'!"); in logic and mathematics, this is discussing a converse relation. Alice also ponders what it means when the changing of seats around the circular table places them back at the beginning. This is an observation of addition on the ring of integers modulo N.

- The Cheshire cat fades until it disappears entirely, leaving only its wide grin, suspended in the air, leading Alice to marvel and note that she has seen a cat without a grin, but never a grin without a cat. Deep abstraction of concepts, such as non-Euclidean geometry, abstract algebra, and the beginnings of mathematical logic, was taking over mathematics at the time Dodgson was writing. Dodgson's delineation of the relationship between cat and grin can be taken to represent the very concept of mathematics and number itself. For example, instead of considering two or three apples, one may easily consider the concept of 'apple', upon which the concepts of 'two' and 'three' may seem to depend. A far more sophisticated jump is to consider the concepts of 'two' and 'three' by themselves, just like a grin, originally seemingly dependent on the cat, separated conceptually from its physical object.

Eating and devouring

Carina Garland notes how the world is "expressed via representations of food and appetite", naming Alice's frequent desire for consumption (of both food and words), her 'Curious Appetites'.[24] Often, the idea of eating coincides to make gruesome images. After the riddle "Why is a raven like a writing-desk?", the Hatter claims that Alice might as well say, "I see what I eat…I eat what I see" and so the riddle's solution, put forward by Boe Birns, could be that "A raven eats worms; a writing desk is worm-eaten"; this idea of food encapsulates idea of life feeding on life, for the worm is being eaten and then becomes the eater – a horrific image of mortality.[25]

Nina Auerbach discusses how the novel revolves around eating and drinking which "motivates much of her [Alice's] behaviour", for the story is essentially about things "entering and leaving her mouth".[26] The animals of Wonderland are of particular interest, for Alice's relation to them shifts constantly because, as Lovell-Smith states, Alice's changes in size continually reposition her in the food chain, serving as a way to make her acutely aware of the ‘eat or be eaten’ attitude that permeates Wonderland.[27]

Illustrations

The manuscript was illustrated by Dodgson himself who added 37 illustrations—printed in a facsimile edition in 1887.[12]:117 John Tenniel provided 42 wood engraved illustrations for the published version of the book. The first print run was destroyed (or sold to the United States[28]) at Carroll's request because he was dissatisfied with the quality. The book was reprinted and published in 1866.[12]

John Tenniel's illustrations of Alice do not portray the real Alice Liddell, who had dark hair and a short fringe. The Guardian states, “John Tenniel’s illustrations to this first edition remain indelibly Alice, with her apron and puffed sleeves and sweep of blond hair.”[29] Alice has provided a challenge for other illustrators, including those of 1907 by Charles Pears and the full series of colour plates and line-drawings by Harry Rountree published in the (inter-War) Children's Press (Glasgow) edition. Other significant illustrators include: Arthur Rackham (1907), Willy Pogany (1929), Mervyn Peake (1946), Ralph Steadman (1967), Salvador Dalí (1969), Graham Overden (1969), Max Ernst (1970), Peter Blake (1970), Tove Jansson (1977), Anthony Browne (1988), Helen Oxenbury (1999), and Lisbeth Zwerger (1999).

Publication history

On 26 November 1865, Dodgson's tale was published by Macmillan of London as Alice's Adventures in Wonderland under the pseudonym "Lewis Carroll" with illustrations by John Tenniel.[30] The first print run of 2,000 was held back because Tenniel objected to the print quality.[12] A new edition, released in December of the same year for the Christmas market, but carrying an 1866 date, was quickly printed.[30] The text blocks of the original edition were removed from the binding and sold with Dodgson's permission to the New York publishing house of D. Appleton & Company. The binding for the Appleton Alice was identical to the 1866 Macmillan Alice, except for the publisher's name at the foot of the spine. The title page of the Appleton Alice was an insert cancelling the original Macmillan title page of 1865, and bearing the New York publisher's imprint and the date 1866.[30]

The entire print run sold out quickly. Alice was a publishing sensation, beloved by children and adults alike.[30] Among its first avid readers were Queen Victoria and the young Oscar Wilde.[31][32][33] The book has never been out of print.[30] Alice's Adventures in Wonderland has been translated into at least 97 languages,[4] or as many as 174 languages.[34] There have now been over a hundred editions of the book, as well as countless adaptations in other media, especially theatre and film.

The book is commonly referred to by the abbreviated title Alice in Wonderland, which has been popularised by the numerous stage, film and television adaptations of the story produced over the years. Some printings of this title contain both Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and its sequel Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There.

Publication timeline

The following list is a timeline of major publication events related to Alice's Adventures in Wonderland:

- 1865: First U.K. edition (the second printing); first U.S. edition (the first printing of U.K. edition).[35]

- 1869: Published in German as Alice's Abenteuer im Wunderland, translated by Antonie Zimmermann.[36]

- 1869: Published in French as Aventures d'Alice au pays des merveilles, translated by Henri Bué.[37]

- 1870: Published in Swedish as Alice's Äventyr i Sagolandet, translated by Emily Nonnen.[38]

- 1871: Dodgson meets another Alice, Alice Raikes, during his time in London. He talks with her about her reflection in a mirror, leading to the sequel, Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There, which sells even better.

- 1872: Published in Italian as Le Avventure di Alice nel Paese delle Meraviglie, translated by Teodorico Pietrocòla Rossetti.[39]

- 1879: First Russian edition published as Соня в царстве Дива, translated by Yury Nesterenko.[40]

- 1882: Selchow & Righter releases The Game of Alice in Wonderland, the first game based on the book.[41]

- 1886: Carroll publishes a facsimile of the earlier Alice's Adventures Under Ground manuscript.

- 1890: Carroll publishes The Nursery "Alice", a special edition "to be read by Children aged from Nought to Five".

- 1899: First Japanese edition of an Alice novel is published as 鏡世界, a translation of Through the Looking-Glass rather than the first book.[42]

- 1905: Mrs J. C. Gorham publishes Alice's Adventures in Wonderland Retold in Words of One Syllable in a series of such books published by A. L. Burt Company, aimed at young readers. (ISBN 978-1-904808-44-2)

- 1906: Published in Finnish as Liisan seikkailut ihmemaailmassa, translated by Anni Swan.[42]

- 1907: Copyright on Alice's Adventures in Wonderland expires in UK, entering the tale into the public domain. At least 8 new editions would be published in this year alone.[43]

- 1910: Published in Esperanto as La Aventuroj de Alicio en Mirlando, translated by E. L. Kearney.[42]

- 1915: A dramatic screenplay script rendering of Alice in Wonderland by Alice Gerstenberg is published as Alice in Wonderland; a dramatization of Lewis Carrolls 'Alices adventures in Wonderland' and 'Through the looking glass.[44]

- 1916: First edition of the Windermere Series is published: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, illustrated by Milo Winter.[42]

- 1928: The manuscript of Alice's Adventures Under Ground written and illustrated by Carroll, which he had given to Alice Liddell, was sold at Sotheby's on 3 April. It sold to Philip Rosenbach for £15,400, a world record for the sale of a manuscript at the time.[45]

- 1945: Animated picture book is published, with illustrations and paper engineering by Julian Wehr.[46]

- 1960: American writer Martin Gardner publishes a special edition, The Annotated Alice, incorporating the text of both Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. It includes extensive annotations explaining the hidden allusions in the books, as well as full texts of the Victorian-era poems parodied in them. Later editions expand on these annotations.[47]

- 1961: The Folio Society edition is published, including 42 illustrations by John Tenniel.

- 1988: Lewis Carroll and Anthony Browne, illustrator of an edition from Julia MacRae Books, wins the Kurt Maschler Award (aka the Emil) for the year's best British "work of imagination for children, in which text and illustration are integrated so that each enhances and balances the other."[48]

- 1998: Carroll's own copy of Alice, one of only six surviving copies of the 1865 first edition, is sold at an auction for US$1.54 million to an anonymous American buyer, becoming the most expensive children's book (or 19th-century work of literature) ever sold to that point.[49]

- 1999: Lewis Carroll and Helen Oxenbury, illustrator of an edition from Walker Books, win the Kurt Maschler Award for integrated writing and illustration.[48]

- 2001: Harper Collins publishes an edition with illustrations by Deloss McGraw.[50]

- 2007: In celebration of the British Kate Greenaway Medal's 50th anniversary (1955–2005), the 1999 Walker Books edition illustrated by Helen Oxenbury is named as one of the top ten Medal-winning works, composing the ballot for a public election of the all-time favourite.[51]

- 2008: Folio publishes Alice's Adventures Under Ground facsimile edition (limited to 3,750 copies, boxed with The Original Alice pamphlet).

- 2009: Children's book collector and former American football player Pat McInally reportedly sold Alice Liddell's own copy at auction for US$115,000.[52]

Reception by reviewers

The book Alice in Wonderland failed to be named in an 1888 poll of the publishing season's most popular children's stories. Generally it received poor reviews, with reviewers giving more credit to Tenniel's illustrations than to Carroll's story. At the release of Through the Looking-Glass, the first Alice tale gained in popularity and by the end of the 19th century Sir Walter Besant wrote that Alice in Wonderland "was a book of that extremely rare kind which will belong to all the generations to come until the language becomes obsolete".[53]

In 2014, Robert McCrum named the tale "one of the best loved in the English canon", and called it "perhaps the greatest, possibly most influential, and certainly the most world-famous Victorian English fiction".[30]

Adaptations and influence

.jpg)

In 2015, Robert Douglas-Fairhurst in The Guardian wrote, “Since the first publication of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland 150 years ago, Lewis Carroll’s work has spawned a whole industry, from films and theme park rides to products such as a 'cute and sassy' Alice costume ('petticoat and stockings not included'). The blank-faced little girl made famous by John Tenniel's original illustrations has become a cultural inkblot we can interpret in any way we like."[5]

Alice and the rest of Wonderland continue to inspire or influence many other works of art to this day, sometimes indirectly via the 1951 Disney movie, for example. References, homages, reworkings and derivative works can be found in many works of literature, film, theatre, visual art, music, and games (such as playing cards).[54] Labelled “a dauntless, no-nonsense heroine” by The Guardian, the character of the plucky, yet proper, Alice has proven immensely popular and inspired similar heroines in literature and pop culture, many also named Alice in homage.[55]

Cinema and television

The book has inspired numerous film and television adaptations which have multiplied as the original work is now in the public domain in all jurisdictions. The following list is of direct adaptations of Adventures in Wonderland (sometimes merging it with Through the Looking-Glass), not other sequels or works otherwise inspired by the works (such as Tim Burton's 2010 film Alice in Wonderland):

.jpg)

- Alice in Wonderland (1903), a British silent film directed by Cecil Hepworth and Percy Stow, with May Clark as Alice.[56]

- Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1910), a silent film directed by Edwin Stanton Porter

- Alice in Wonderland (1915), a silent film directed by W. W. Young

- Alice in Wonderland (1931), the first talkie adaptation, directed by Bud Pollard

- Alice in Wonderland (1933), a film version directed by Norman Z. McLeod, US

- Alice in Wonderland (1937), a TV adaptation directed by George More O'Ferrall

- Alice in Wonderland (1937) TV adaptation again directed by George More O'ferrall with Usula Henray as Alice.[57]

- Alice in Wonderland (1944) TV adaptation of Eva La Gaillenne's stage version of both books, US.[58]

- Alice (1946), a BBC production starring Vivian Pickles directed by George More O'Ferrall, UK

- Alice in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass (1948) BBC TV broadcast.[59]

- Alice in Wonderland (1949), a live-action/animated film with stop motion segments, directed by Dallas Bower

- Through the Crystal Ball: Alice in Wonderland (1949) US TV performance.[60]

- Alice in Wonderland (1950), televised on the CBS Ford Theatre, with Iris Mann as Alice, directed by Franklin J. Schaffner

- Alice in Wonderland (1951), a film version in traditional animation from Walt Disney Feature Animation. Arguably the most well known of the Alice film adaptations, and today considered one of Disney's great classics.[61]

- Alice au pays des Merveilles (1951) France TV broadcast of a stage version

- Alice in Wonderland (1954) BBC broadcast of a ballet version.[62]

- Alice in Wonderland (1955), a live television adaptation of the 1932 Eva LeGallienne /Florida Friebus stage adaptation of the novel, directed for television by George Schaefer for the Hallmark Hall of Fame

- The Adventures of Alice (1960) Televised opera.[63]

- The BP Super Show: Alice in Wonderland (1962) Australian TV musical special.[64]

- Alice in Wonderland (1965), a TV movie directed by Dennis Potter

- Alice in Wonderland (1966), an animated Hanna-Barbera TV movie with Janet Waldo as Alice

- Alice in Wonderland (1966), a BBC television play directed by Jonathan Miller

- Alice au pays des merveilles (1972), a version made for television, by Jean-Christophe Averty.

- Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (1972), a musical film version starring Fiona Fullerton as Alice

- Alice in Wonderland (sometimes listed as Alice in Wonderland: An X-Rated Musical Comedy) (1976), an American erotic musical comedy film, starring Kristine DeBell

- Nel Mondo Di Alice (In the World of Alice) Italian TV series in 4 parts.[65]

- Alice in Wonderland (1983), a PBS Great Performances presentation of a 1982 stage play which was in turn a revival of the 1932 LeGallienne production

- Alice in Wonderland (1985), a two-part made-for-TV special produced by Irwin Allen and featuring a large all-star cast

- Alice in a Winter Wonderland (1985): a BBC One Christmas Special parody, performed by sketch-comedy duo The Two Ronnies, featuring Ronnie Barker and Ronnie Corbett.[66][67]

- Alice in Wonderland (1986), a BBC adaptation directed by Barry Letts and starring Kate Dorning

- Alice (1988 film) by Jan Švankmajer, stop motion and live action

- Alice in Wonderland (1995), an animated film by Jetlag Productions and directed by Toshi Hiruma

- Alice in Wonderland (1999), a 1999 television movie first shown on NBC and then shown on British television on Channel 4

- Once Upon a Time in Wonderland (2013–2014): an American fantasy-drama series that parodies the Alice tales, created by Edward Kitsis, Adam Horowitz, Zack Estrin, and Jane Espenson for ABC Studios.[68]

Comic strips and books

Alice in Wonderland (1934–1935) was a comic strip adaptation drawn by Edward D. Kuekes and written by Olive Ray Scott. This version also featured a "topper" strip, Knurl the Gnome. The strip was distributed by United Feature Syndicate.[69]

Literary and comic-book adaptations include:

- The Westminster Alice (1902): a parody by Hector Hugh Munro (Saki), illustrated by Francis Carruthers Gould

- Walt Disney's Alice in Wonderland (1951, Dell Comics)

- Walt Disney's Alice in Wonderland (1965, Gold Key Comics)

- Walt Disney's Alice in Wonderland (Whitman, 1984)

- "The Complete Alice in Wonderland" (2005, Dynamite Entertainment)

- Return to Wonderland (2009, Zenescope Entertainment)

- Alice in Wonderland (2011, Zenescope Entertainment)

- Alice in Weirdworld (2020, Flying Buffalo Incorporated)

Live performance

The first full major production of 'Alice' books during Carroll's lifetime was Alice in Wonderland, an 1886 musical play in London's West End by H. Saville Clark (book) and Walter Slaughter (music), which played at the Prince of Wales Theatre. The musical was frequently revived during West End Christmas seasons during the four decades after its premiere, including a London production at the Globe Theatre in 1888, with Isa Bowman as Alice.[70]

As the book and its sequel are Carroll's most widely recognised works, they have also inspired numerous live performances, including plays, operas, ballets, and traditional English pantomimes. These works range from fairly faithful adaptations to those that use the story as a basis for new works. An example of the latter is The Eighth Square, a murder mystery set in Wonderland, written by Matthew Fleming and music and lyrics by Ben J. Macpherson. This goth-toned rock musical premiered in 2006 at the New Theatre Royal in Portsmouth, England. The TA Fantastika, a popular Black light theatre in Prague performs "Aspects of Alice"; written and directed by Petr Kratochvíl. This adaptation is not faithful to the books, but rather explores Alice's journey into adulthood while incorporating allusions to the history of Czech Republic.

Over the years, many notable people in the performing arts have been involved in Alice productions. Actress Eva Le Gallienne famously adapted both Alice books for the stage in 1932; this production has been revived in New York in 1947 and 1982. One of the most well-known American productions was Joseph Papp's 1980 staging of Alice in Concert at the Public Theater in New York City. Elizabeth Swados wrote the book, lyrics, and music. Based on both Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, Papp and Swados had previously produced a version of it at the New York Shakespeare Festival. The actress Meryl Streep played Alice, the White Queen, and Humpty Dumpty.[71] The cast also included Debbie Allen, Michael Jeter, and Mark Linn-Baker. Performed on a bare stage with the actors in modern dress, the play is a loose adaptation, with song styles ranging the globe. A community theater production of Alice was Olivia de Havilland's first foray onto the stage.

.jpg)

Similarly, the 1992 operatic production Alice used both Alice books as its inspiration. It also employs scenes with Charles Dodgson, a young Alice Liddell, and an adult Alice Liddell, to frame the story. Paul Schmidt wrote the play, with Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan writing the music. Although the original production in Hamburg, Germany, received only a small audience, Tom Waits released the songs as the album Alice in 2002. A musical adaption was written by Michael Sirotta and Heather M. Dominick in 1997, titled Alice in Wonderland, a Musical Adventure.[72][73]

The English composer Joseph Horovitz composed an Alice in Wonderland ballet commissioned by the London Festival Ballet in 1953. It was performed frequently in England and the US.[74] A ballet by Christopher Wheeldon and Nicholas Wright commissioned for The Royal Ballet entitled Alice's Adventures in Wonderland premiered in February 2011 at the Royal Opera House in London.[75][76] The ballet was based on the novel Wheeldon grew up reading as a child and is generally faithful to the original story, although some critics claimed it may have been too faithful.[77] The ballet overall stays generally light hearted for its running time of an hour and forty minutes. The ballet returned to the Royal Opera House in 2012.[78]

Gerald Barry's 2016 one-act opera, Alice's Adventures Under Ground, first staged in 2020 at the Royal Opera House, is a conflation of the two Alice books.[79]

Gallery

The cover illustration of The Nursery "Alice", by E. Gertrude Thomson

The cover illustration of The Nursery "Alice", by E. Gertrude Thomson_-_The_Nursery_Alice_(1890)_-_BL.jpg) The White Rabbit by John Tenniel, coloured

The White Rabbit by John Tenniel, coloured Mad tea party, John Tenniel, 1865

Mad tea party, John Tenniel, 1865 Statue of Alice in Rymill Park, Adelaide, South Australia

Statue of Alice in Rymill Park, Adelaide, South Australia Alice in Wonderland sculpture in Central Park, New York

Alice in Wonderland sculpture in Central Park, New York Lewis Carroll memorial window at All Saints' Church, Daresbury, Cheshire

Lewis Carroll memorial window at All Saints' Church, Daresbury, Cheshire

See also

References

- BBC's Greatest English Books list

- Lecercle, Jean-Jacques (1994) Philosophy of nonsense: the intuitions of Victorian nonsense literature Routledge, New York. ISBN 978-0-415-07652-4. p. 1 ff

- Schwab, Gabriele (1996) "Chapter 2: Nonsense and Metacommunication: Alice in Wonderland" in The mirror and the killer-queen: otherness in literary language Indiana University Press, Bloomington, Indiana. ISBN 978-0-253-33037-6. pp. 49–102

- Bandersnatch: The Newsletter of The Lewis Carroll Society, Issue 149 (January 2011). p. 11.

- "Alice in Wonderland: the never-ending adventures". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "The real Alice". Story Museum. Archived from the original on 17 November 2010. Retrieved 24 April 2010.

- Lewis Carroll, "Alice on the Stage, The Theatre, April 1887

- Astronomical and Meteorological Observations Made at the Radcliffe Observatory, Oxford, Vol. 23

- The Background & History of Alice In Wonderland. Bedtime-Story Classics. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- "Meet the Girl Who Inspired 'Alice in Wonderland'". The Atlantic. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1985). Secret Gardens: The Golden Age of Children's Literature. Houghton Mifflin. p. 57. ISBN 978-0-395-35293-9.

- Ray, Gordon Norton (1991). The Illustrator and the book in England from 1790 to 1914. New York: Dover. p. 117. ISBN 978-0-486-26955-9.

- Gardner, Martin (2000). The Annotated Alice: The Definitive Edition. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04847-6.

- Everson, Michael (2009) "Foreword", in Carroll, Lewis (2009). Alice's Adventures under Ground. Evertype. ISBN 978-1-904808-39-8.

- Brooker, Will (2004). Alice's Adventures: Lewis Carroll in Popular Culture. New York: Continuum. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-8264-1433-5.

- The diary of Lewis Carroll, 1 August 1862 entry

- Coward, Leon (November 2015). "Alice in Wonderland: 150 years". The Greek Australian Vema. Sydney, Australia: St Andrews Orthodox Press. p. 18.

- "Ripon Tourist Information". Hello-Yorkshire.co.uk. Archived from the original on 26 November 2009. Retrieved 1 December 2009.

- "Alice's Adventures In Wonderland Turns 150". Marie Claire. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- Gardner, Martin (1990). More Annotated Alice. New York: Random House. p. 363. ISBN 978-0-394-58571-0.

- Lewis Carroll (2009). Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-955829-2.

- Bayley, Melanie (6 March 2010). "Algebra in Wonderland". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 12 March 2010. Retrieved 13 March 2010.

- Bayley, Melanie. "Alice's adventures in algebra: Wonderland solved". New Scientist. Retrieved 21 August 2012.

- Garland, C. (2008). "Curious Appetites: Food, Desire, Gender and Subjectivity in Lewis Carroll's Alice Texts". The Lion and the Unicorn. 32: 22–39. doi:10.1353/uni.2008.0004.

- Boe Birns, Margaret (1984). "Solving the Mad Hatter's Riddle". The Massachusetts Review. 25 (3): 457–468 (462). JSTOR 25089579.

- Auerbach, Nina (1973). "Alice and Wonderland: A Curious Child". Victorian Studies. 17 (1): 31–47 (39). JSTOR 3826513.

- Lovell-Smith, R. (2004). "The Animals of Wonderland: Tenniel as Carroll's Reader". Criticism. 45 (4): 383–415. doi:10.1353/crt.2004.0020.

- Ovenden, Graham (1972). The Illustrators of Alice. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-902620-25-4.

- "The Guardian view on Alice in Wonderland: a dauntless, no-nonsense heroine". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- "The 100 best novels: No 18 – Alice's Adventures in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll (1865)". The Guardian. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "10 things you didn't know about Alice in Wonderland". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 October 2019.

- Tucker, Rebecca (25 February 2011). "Oscar Reads: Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, by Lewis Carroll". Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- "Alice in Wonderland". QI. Quite Interesting Ltd. Archived from the original on 22 April 2017. Retrieved 15 April 2017.

- "Alice in a World of Wonderlands – The Books". aliceinaworldofwonderlands.com.

- Carroll, Lewis (1995). The Complete, Fully Illustrated Works. New York: Gramercy Books. ISBN 978-0-517-10027-1.

- "Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland – in German". Evertype.com. Retrieved 28 October 2019

- "Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland – in French". Evertype.com. Retrieved 28 October 2019

- "Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland – in Swedish". Evertype.com. Retrieved 28 October 2019

- "Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland – in Italian". Evertype.com. Retrieved 28 October 2019

- "Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland – in Russian". Evertype.com. Retrieved 28 October 2019

- "Pastimes: Children's Games and Their Literary Inspirations". Indiana University. Retrieved 9 October 2012.

- “Wonderland and Carrolliana”. Evertype.com. Retrieved 28 October 2019

- Page 11 of Introduction, by John Davies, of Ovenden, Graham (1972). The Illustrators of Alice. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-902620-25-4.

- Gerstenberg, Alice (1915). Alice in Wonderland; a dramatization of Lewis Carrolls "Alices adventures in Wonderland" and "Through the looking glass," Chicago: A. C. McClurg & Co. Produced by the Players Producing Company of Chicago, at the Fine Arts Theater, Chicago (2/11/1915) and Booth Theater, New York (3/23/1915).

- Basbanes, Nicholas (1999). A Gentle Madness: Bibliophiles, Bibliomanes, and the Eternal Passion for Books. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-8050-6176-5.

- Wehr, Julian; Carroll, Lewis. The animated picture book of Alice in Wonderland. OCLC 11319992.

- Self, Will (25 December 2000). "Dirty Old Man" on The New Statesman. Review.

- "Kurt Maschler Awards". Book Awards. bizland.com. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- "Auction Record for an Original 'Alice'". The New York Times. 11 December 1998. p. B30.

- “Alice's Adventures in Wonderland”. Publishers Weekly. Retrieved 28 October 2019

- "70 Years Celebration: Anniversary Top Tens" Archived 27 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine. The CILIP Carnegie & Kate Greenaway Children's Book Awards. CILIP. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- "Real Alice in Wonderland book sells for $115,000 in USA". BBC News. 17 December 2009. Retrieved 8 January 2012.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1985). Secret Gardens: The Golden Age of Children's Literature. Houghton Mifflin. p. 68. ISBN 978-0-395-35293-9.

- "Novels About Playing Cards: Alice in Wonderland". 6 May 2020. Retrieved 7 May 2020.

- "The Guardian view on Alice in Wonderland: a dauntless, no-nonsense heroine". The Guardian. Retrieved 5 November 2019.

- Mills, Ted (31 March 2016). "The First Film Adaptation of Alice in Wonderland (1903)". Open Culture. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- "Phantomwise". Phantomwise. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- "Phantomwise". Phantomwise. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- "Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass". British Universities Film & Video Council. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- "Phantomwise". Phantomwise. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- Louis Peitzman, "17 Adaptations Of "Alice's Adventures In Wonderland" Through The Years", BuzzFeed (11 October 2013), describing the 1951 Disney film as "undoubtedly the most well known".

- "All-in-the-golden-afternoon96, still-she-haunts-me-phantomwise: London's..." All-in-the-golden-afternoon96. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- "Phantomwise". Phantomwise. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- "Phantomwise". Phantomwise. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- fictionrare2 (29 September 2014), Nel mondo di Alice 1p, retrieved 23 April 2016

- "Episode #12.1" – via www.imdb.com.

- "Watch two classic Two Ronnies Christmas songs". Smooth Radio.

- Hibberd, James (13 May 2013). "'Once Upon a Time' to crossover with 'Wonderland' spin-off". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- "Ed Kuekes". Lambiek Comiclopedia. Lambiek. 11 April 2008. Retrieved 9 August 2017.

- Moses, Belle (2009). Lewis Carroll in Wonderland and at Home: The Story of His Life. BiblioBazaar. pp. 244–247. ISBN 978-1-103-29348-3.

- "'Alice' Through the Years: 16 Actresses Who Played the Iconic Character". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 15 April 2020.

- "Winter Children's Theatre "Alice in Wonderland" Runs Through March 24th". North Coast Oregon. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- "First Redeemer conservatory of music and fine arts presents Alice in Wonderland". APPEN MEDIA GROUP. Retrieved 9 January 2015.

- "Horovitz Alice in Wonderland (excs)". Gramophone.co.uk. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- "Royal Ballet Takes a Chance on Alice". Time. 3 March 2011.

- "Joby Talbot – Alice's Adventures in Wonderland (2010) – Music Sales Classical". Chesternovello.com. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- Sulcas, Roslyn (1 March 2011). "'Alice in Wonderland' at the Royal Ballet – Review". The New York Times.

- "Calendar < Events – Royal Opera House < August 2013". Roh.org.uk. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- "Alice's Adventures Under Ground". Royal Opera House. Retrieved 6 February 2020.

Citations

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1985). Secret Gardens: The Golden Age of Children's Literature. Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-35293-9.

- Gardner, Martin (2000). The Annotated Alice: the definitive edition. New York and London: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04847-6.

- Ray, Gordon Norton (1991). The Illustrator and the book in England from 1790 to 1914. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-26955-9.

External links

- Project Gutenberg:

- Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, plain text

- Alice's Adventures Under Ground, HTML with facsimiles of original manuscript pages, and illustrations by Carroll

- LibriVox:

- GASL.org: First editions of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland and Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There With 92 Illustrations by Tenniel, 1866/1872.

- Images of the 1st editions of the book and other works by Lewis Carroll: https://sites.google.com/site/lewiscarroll1steditions/

- British Library: Original manuscript and drawings by Lewis Carroll (requires Flash)

- Afterlife of Alice and Her Adventures in Wonderland is a collection of various editions of Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, Through the Looking-Glass, What Alice Found There, and other similar works.