Afghanistan conflict (1978–present)

The Afghanistan conflict (Persian: جنگ های افغانستان, Pashto: د افغانستان جنګونه) is a series of wars that has been fought in Afghanistan since 1978. Starting with the Saur Revolution military coup, an almost continuous series of armed conflicts has dominated and afflicted Afghanistan. The wars include:

- The Soviet–Afghan War began in 1979 and ended in 1989. The Soviet Army "invaded" or "intervened" in the country to secure the ruling People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA) following large waves of rebellion against the government. Soviet troops along with the allied Afghan Army fought against rebel factions mostly known collectively as the "Afghan mujahideen", whose main backers were the Soviet Union's Cold War enemies the United States and Pakistan. The Soviet Union was forced to withdraw its troops in 1989.

- The Afghan Civil War (1989–92) was the continuing war between the government and rebels, but without the involvement of Soviet troops. The Soviet Union nevertheless continued to financially support the Afghan government in its fight, and likewise rebel factions continued receiving support from the United States and Pakistan. The Soviet-backed Afghan government survived until the fall of Kabul in 1992.

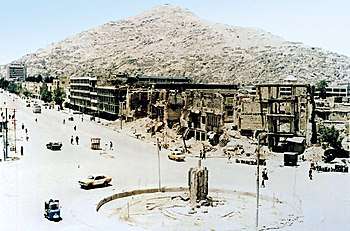

- The Afghan Civil War (1992–96) began when infighting between the mujahideen rebel factions, after taking Kabul and establishing the Islamic State of Afghanistan, escalated into another full blown conflict. Violent wars were fought between different occupying factions in Kabul, and the city experienced heavy bombardment from them. Each of these were supported by an outside power, such as Pakistan, Iran, or Saudi Arabia, who were seeking influence in Afghanistan. This conflict ended in 1996 after the Taliban, a relatively new militia backed by Pakistan and enforced by several thousand al-Qaeda fighters from Arab countries, took Kabul.

- The Afghan Civil War (1996–2001) started immediately after the Taliban's capture of Kabul which involved a new military-political resistance force called Northern Alliance fighting against the Taliban and their partially recognized Emirate. Throughout this period the Taliban were in control of almost all of the country, as the Northern Alliance fought most of the time on the defense. The Alliance's leader was assassinated by al-Qaeda members on September 9, 2001.

- The United States invasion of Afghanistan started on October 7, 2001. The United States sought to remove the Taliban from power as they were hosting al-Qaeda terrorists and camps, who were the main suspects of the September 11 attacks. The United States fought the Taliban from the air and provided support to Northern Alliance ground troops, who successfully drove the Taliban away from most of the country by December 2001. The invasion also marked the start of the United States's War on Terror.

- The War in Afghanistan (2001–present) is the continuous incumbent war in Afghanistan, where the main conflict consists of Afghan Army troops, backed by additional United States troops, fighting against insurgents of the Taliban and sporadically other groups as well.[6] NATO has also been involved in this war.

It has been estimated that 1,405,111 to 2,084,468 lives have been lost since the start of the conflict.[1][2][3][4][5]

Rise and fall of communism

Prelude

From 1933 to 1973 Afghanistan experienced a lengthy period of peace and relative stability.[7] It was ruled as a monarchy by King Zahir Shah, who belonged to the Afghan Musahiban Barakzai dynasty.[7][8] In the 1960s, Afghanistan as a constitutional monarchy held limited parliamentary elections.[9]

Zahir Shah, who would become the last King of Afghanistan, was overthrown by his cousin Mohammed Daoud Khan in July 1973, after discontent with the monarchy grew in the urban areas of Afghanistan.[7] The country had gone through several droughts, and charges of corruption and poor economic policies were leveled against the ruling dynasty. Khan transformed the monarchy into a republic, and he became the first President of Afghanistan. He was supported by a faction of the People's Democratic Party of Afghanistan (PDPA), Afghanistan's communist party, which had been founded in 1965 and enjoyed strong relations with the Soviet Union. Neamatollah Nojumi writes in The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass Mobilization, Civil War, and the Future of the Region:

The establishment of the Republic of Afghanistan increased the Soviet investment in Afghanistan and the PDPA influence in the government's military and civil bodies.[10]

In 1976, alarmed by the growing power of the PDPA and the party's strong affiliation with the Soviet Union, Daoud Khan tried to scale back the PDPA's influence.[11] He dismissed PDPA members from their government posts, appointed conservative elements instead and finally announced the dissolution of the PDPA, arresting senior party members.[10]

Communist coup

.jpg)

On April 27, 1978, the PDPA and military units loyal to the PDPA killed Daoud Khan, his immediate family and bodyguards in a violent coup, seizing control of the capital, Kabul.[12] As the PDPA had chosen a weekend holiday to conduct the coup, when many government employees were having a day off, Daoud Khan was not able to fully activate the well-trained armed forces which remained loyal to him to counter the coup.[12]

The new PDPA government, led by a revolutionary council, did not enjoy the support of the masses.[13] Therefore, it soon announced and implemented a hostile doctrine against any political dissent, whether inside or outside the party.[10] The first communist leader in Afghanistan, Nur Muhammad Taraki, was assassinated by his fellow communist Hafizullah Amin.[14] Amin was known for his independent and nationalist inclinations, and was also seen by many as a ruthless leader. He has been accused of killing tens of thousands of Afghan civilians at Pul-e-Charkhi and other national prisons: 27,000 politically motivated executions reportedly took place at Pul-e-Charkhi prison alone.[15]

Soviet intervention and withdrawal

The Soviet Union intervened in Afghanistan on December 24, 1979. Amin was deposed from power almost immediately, as he and 200 of his guards were killed on December 27 by Soviet Army Spetsnaz, replaced by Babrak Karmal. After deployment into Afghanistan, Soviet forces along with government forces would begin to engage in a protracted counter-insurgency war with mujahideen fighters. Some of those Islamic fighters would later transform into the Taliban according to Professor Carole Hillenbrand who stated: "The West helped the Taliban to fight the Soviet takeover of Afghanistan".[16]

The Soviet government realized that a military solution to the conflict would require far more troops. Because of this they discussed troop withdrawals and searched for a political and peaceful solution as early as 1980, but they never took any serious steps in that direction until 1988. Early Soviet military reports confirm the difficulties the Soviet army had while fighting on the mountainous terrain, for which the Soviet army had no training whatsoever. Parallels with the Vietnam War were frequently referred to by Soviet army officers.[17]

Policy failures, and the stalemate that ensued after the Soviet intervention, led the Soviet leadership to become highly critical of Karmal's leadership. Under Mikhail Gorbachev, the Soviet Union was able to depose Karmal and replace him with Mohammad Najibullah. Karmal's leadership was seen as a failure by the Soviet Union because of the rise of violence and crime during his administration.

Throughout the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, troop convoys came under attack by Afghan rebel fighters. In all, 523 Soviet soldiers were killed during the withdrawal. The total withdrawal of all Soviet troops from Afghanistan was completed in February 1989.[18] The last Soviet soldier to leave was Lieutenant General Boris Gromov, leader of the Soviet military operations in Afghanistan at the time of the Soviet invasion.[19] In total 14,453 Soviet soldiers died during the Afghan war.

The Soviet war had a damaging impact on Afghanistan. The deaths of up to 2 million Afghans in the war has been described as "genocide" by a number of sources.[20][21][22] Five to ten million Afghans fled to Pakistan and Iran, amounting to 1/3 of the prewar population of the country, and another 2 million were displaced within the country. Pakistan's North-West Frontier Province functioned as an organisational and networking base for the anti-Soviet Afghan resistance, with the province's influential Deobandi ulama playing a major supporting role in promoting the 'jihad'.[23]

Fall of communism

After the Soviet withdrawal, the Republic of Afghanistan under Najibullah continued to face resistance from the various mujahideen forces. Najibullah received funding and arms from the Soviet Union until 1991 when the Soviet Union collapsed.[24] For several years the Afghan Army had actually increased their effectiveness past levels ever achieved during the Soviet military presence. But the government was dealt a major blow when Abdul Rashid Dostum, a leading general, created an alliance with the Shura-e Nazar of Ahmad Shah Massoud. Large parts of the Afghan communist government capitulated to the forces of Massoud in early 1992. After the Soviet defeat, The Wall Street Journal named Massoud "the Afghan who won the Cold War".[25] He had defeated the Soviet forces nine times in his home region of the Panjshir Valley in northeastern Afghanistan.[26]

Pakistan tried to install Gulbuddin Hekmatyar in power in Afghanistan against the opposition of all other mujahideen commanders and factions.[27] As early as October 1990, the Inter-Services Intelligence had devised a plan for Hekmatyar to conduct a mass bombardment of the Afghan capital Kabul with possible Pakistani troop enforcements.[27] This unilateral ISI-Hekmatyar plan came although the thirty most important mujahideen commanders had agreed on holding a conference inclusive of all Afghan groups to decide on a common future strategy.[27] Peter Tomsen reports that the protest by the other mujahideen commanders was like a "firestorm". Ahmad Zia Massoud, the brother of Ahmad Shah Massoud, said that his faction strongly opposed the plan and like other factions would take measures if any "Pakistani troops reinforced Hekmatyar". Abdul Haq was reportedly so angry about the ISI plan that he was "red in the face".[27] And Nabi Mohammad, another commander, pointed out that "Kabul's 2 million could not escape Hekmatyar's rocket bombardment – there would be a massacre."[27] Massoud's, Abdul Haq's and Amin Wardak's representatives said that "Hekmatyar's rocketing of Kabul ... would produce a civilian bloodbath."[27] The United States finally put pressure on Pakistan to stop the 1990 plan, which was subsequently called off until 1992.[27]

Islamic State and foreign interference

After the fall of Najibullah's government in 1992, the Afghan political parties agreed on a power-sharing agreement, the Peshawar Accord. The Peshawar Accord created the Islamic State of Afghanistan and appointed an interim government for a transitional period to be followed by general democratic elections. According to Human Rights Watch:

The sovereignty of Afghanistan was vested formally in the Islamic State of Afghanistan, an entity created in April 1992, after the fall of the Soviet-backed Najibullah government. [...] With the exception of Gulbuddin Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, all of the parties [...] were ostensibly unified under this government in April 1992. [...] Hekmatyar's Hezb-e Islami, for its part, refused to recognize the government for most of the period discussed in this report and launched attacks against government forces and Kabul generally. [...] Shells and rockets fell everywhere.[28]

Gulbuddin Hekmatyar received operational, financial and military support from Pakistan.[29] Afghanistan expert Amin Saikal concludes in Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival:

Pakistan was keen to gear up for a breakthrough in Central Asia. [...] Islamabad could not possibly expect the new Islamic government leaders [...] to subordinate their own nationalist objectives in order to help Pakistan realize its regional ambitions. [...] Had it not been for the ISI's logistic support and supply of a large number of rockets, Hekmatyar's forces would not have been able to target and destroy half of Kabul.[30]

In addition, Saudi Arabia and Iran—as competitors for regional hegemony—supported Afghan militias hostile towards each other.[30] According to Human Rights Watch, Iran was assisting the Shia Hazara Hezb-i Wahdat forces of Abdul Ali Mazari, as Iran was attempting to maximize Wahdat's military power and influence.[28][30][31] Saudi Arabia supported the Wahhabite Abdul Rasul Sayyaf and his Ittihad-i Islami faction.[28][30] Conflict between the two militias soon escalated into a full-scale war. A publication by the George Washington University describes the situation:

[O]utside forces saw instability in Afghanistan as an opportunity to press their own security and political agendas.[32]

Due to the sudden initiation of the war, working government departments, police units or a system of justice and accountability for the newly created Islamic State of Afghanistan did not have time to form. Atrocities were committed by individuals of the different armed factions while Kabul descended into lawlessness and chaos as described in reports by Human Rights Watch and the Afghanistan Justice Project.[28][33] Because of the chaos, some leaders increasingly had only nominal control over their (sub-)commanders.[34] For civilians there was little security from murder, rape and extortion.[34] An estimated 25,000 people died during the most intense period of bombardment by Hekmatyar's Hezb-i Islami and the Junbish-i Milli forces of Abdul Rashid Dostum, who had created an alliance with Hekmatyar in 1994.[33] Half a million people fled Afghanistan.[34] Human Rights Watch writes:

Rare ceasefires, usually negotiated by representatives of Ahmad Shah Massoud, Sibghatullah Mojaddedi or Burhanuddin Rabbani [the interim government], or officials from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), commonly collapsed within days.[28]

Taliban rise to power

Southern Afghanistan was under the control of neither foreign-backed militias nor the government in Kabul, but was ruled by local leaders such as Gul Agha Sherzai and their militias. In 1994, the Taliban (a movement originating from Jamiat Ulema-e-Islam-run religious schools for Afghan refugees in Pakistan) also developed in Afghanistan as a politico-religious force, reportedly in opposition to the tyranny of the local governor.[35] Mullah Omar started his movement with fewer than 50 armed madrassah students in his hometown of Kandahar.[35] When the Taliban took control of the city in 1994, they forced the surrender of dozens of local Pashtun leaders who had presided over a situation of complete lawlessness and atrocities.[34] In 1994, the Taliban took power in several provinces in southern and central Afghanistan.

In late 1994, most of the militia factions (Hezb-i Islami, Junbish-i Milli and Hezb-i Wahdat) which had been fighting in the battle for control of Kabul were defeated militarily by forces of the Islamic State's Secretary of Defense Ahmad Shah Massoud. Bombardment of the capital came to a halt.[33][36][37] Massoud tried to initiate a nationwide political process with the goal of national consolidation and democratic elections, also inviting the Taliban to join the process.[38] Massoud had united political and cultural personalities, governors, commanders, clergymen and representatives to reach a lasting agreement. Massoud, like most people in Afghanistan, saw this conference as a small hope for democracy and for free elections. His favourite for candidacy to the presidency was Dr. Mohammad Yusuf, the first democratic prime minister under Zahir Shah, the former king. In the first meeting representatives from 15 different Afghan provinces met, in the second meeting there were already 25 provinces participating. Massoud went unarmed to talk to several Taliban leaders in Maidan Shar, but the Taliban declined to join this political process.[38] When Massoud returned safely, the Taliban leader who had received him as his guest paid with his life: he was killed by other senior Taliban for failing to execute Massoud while the possibility was there.

The Taliban started shelling Kabul in early 1995 but were defeated by forces of the Islamic State government under Ahmad Shah Massoud.[36] Amnesty International, referring to the Taliban offensive, wrote in a 1995 report:

This is the first time in several months that Kabul civilians have become the targets of rocket attacks and shelling aimed at residential areas in the city.[36]

The Taliban's early victories in 1994 were followed by a series of defeats that resulted in heavy losses.[34] Pakistan provided strong support to the Taliban.[30][39] Many analysts like Amin Saikal describe the Taliban as developing into a proxy force for Pakistan's regional interests which the Taliban decline.[30]

On September 26, 1996, as the Taliban, with military support by Pakistan and financial support by Saudi Arabia, prepared for another major offensive, Massoud ordered a full retreat from Kabul.[40] The Taliban seized Kabul on September 27, 1996, and established the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan.

Taliban Emirate against United Front

Taliban offensives

.png)

The Taliban imposed on the parts of Afghanistan under their control their interpretation of Islam. The Physicians for Human Rights (PHR) stated that:

To PHR's knowledge, no other regime in the world has methodically and violently forced half of its population into virtual house arrest, prohibiting them on pain of physical punishment.[41]

Women were required to wear the all-covering burka, they were banned from public life and denied access to health care and education, windows needed to be covered so that women could not be seen from the outside, and they were not allowed to laugh in a manner that could be heard by others.[41] The Taliban, without any real court or hearing, cut people's hands or arms off when they were accused of stealing.[41] Taliban hit-squads watched the streets, conducting arbitrary brutal public beatings.[41]

The Taliban began preparing offensives against the remaining areas controlled by Ahmad Shah Massoud and Abdul Rashid Dostum. Massoud and Dostum, former foes, responded by allying to form the United Front (Northern Alliance) against the Taliban.[42] In addition to the dominantly Tajik forces of Massoud and the Uzbek forces of Dostum, the United Front included Hazara factions and Pashtun forces under the leadership of commanders such as Abdul Haq or Haji Abdul Qadir. Prominent politicians of the United Front were in example diplomat and Afghan prime minister Abdul Rahim Ghafoorzai or the UF's foreign minister Abdullah Abdullah. From the Taliban conquest in 1996 until November 2001 the United Front controlled roughly 30% of Afghanistan's population in provinces such as Badakhshan, Kapisa, Takhar and parts of Parwan, Kunar, Nuristan, Laghman, Samangan, Kunduz, Ghōr and Bamyan.

According to a 55-page report by the United Nations, the Taliban, while trying to consolidate control over northern and western Afghanistan, committed systematic massacres against civilians.[43][44] UN officials stated that there had been "15 massacres" between 1996 and 2001.[43][44] They also said, that "[t]hese have been highly systematic and they all lead back to the [Taliban] Ministry of Defense or to Mullah Omar himself."[43][44] In a major effort to retake the Shomali plains, the Taliban indiscriminately killed civilians, while uprooting and expelling the population. Kamal Hossein, a special reporter for the UN, reported on these and other war crimes. Upon taking Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998, about 4,000 civilians were executed by the Taliban and many more reported tortured.[45][46] The Taliban especially targeted people of Shia religious or Hazara ethnic background.[43][44] Among those killed in Mazari Sharif were several Iranian diplomats. Others were kidnapped by the Taliban, touching off a hostage crisis that nearly escalated to a full-scale war, with 150,000 Iranian soldiers massed on the Afghan border at one time.[47] It was later admitted that the diplomats were killed by the Taliban, and their bodies were returned to Iran.[48]

The documents also reveal the role of Arab and Pakistani support troops in these killings.[43][44] Bin Laden's so-called 055 Brigade was responsible for mass-killings of Afghan civilians.[49] The report by the United Nations quotes eyewitnesses in many villages describing Arab fighters carrying long knives used for slitting throats and skinning people.[43][44]

Role of the Pakistani Armed Forces

Pakistan's intelligence agency, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI), wanted the Mujahideen to establish a government in Afghanistan. The director-general of the ISI, Hamid Gul, was interested in an Islamic revolution which would transcend national borders, not just in Afghanistan and Pakistan but also in Central Asia. To set up the proposed Mujahideen government, Hamid Gul ordered an assault on Jalalabad-with the intent on using it as the capital for the new government Pakistan was interested in establishing in Afghanistan.[50]

The Taliban were largely funded by Pakistan's ISI in 1994.[51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58] The ISI used the Taliban to establish a regime in Afghanistan which would be favorable to Pakistan, as they were trying to gain strategic depth.[59][60][61][62] Since the creation of the Taliban, the ISI and the Pakistani military have given financial, logistical and military support.[63][64][65]

According to Pakistani Afghanistan expert Ahmed Rashid, "between 1994 and 1999, an estimated 80,000 to 100,000 Pakistanis trained and fought in Afghanistan" on the side of the Taliban.[66] Peter Tomsen stated that up until 9/11 Pakistani military and ISI officers along with thousands of regular Pakistani Armed Forces personnel had been involved in the fighting in Afghanistan.[67]

In 2001 alone, according to several international sources, 28,000–30,000 Pakistani nationals, 14,000–15,000 Afghan Taliban and 2,000–3,000 Al Qaeda militants were fighting against anti-Taliban forces in Afghanistan as a roughly 45,000-strong military force.[38][49][68][69] Pakistani President Pervez Musharraf – then as Chief of Army Staff – was responsible for sending thousands of Pakistanis to fight alongside the Taliban and Bin Laden against the forces of Ahmad Shah Massoud.[38][39][70] Of the estimated 28,000 Pakistani nationals fighting in Afghanistan, 8,000 were militants recruited in madrassas filling regular Taliban ranks.[49] A 1998 document by the U.S. State Department confirms that "20–40 percent of [regular] Taliban soldiers are Pakistani."[39] The document further states that the parents of those Pakistani nationals "know nothing regarding their child's military involvement with the Taliban until their bodies are brought back to Pakistan."[39] According to the U.S. State Department report and reports by Human Rights Watch, the other Pakistani nationals fighting in Afghanistan were regular Pakistani soldiers especially from the Frontier Corps but also from the Pakistani Army providing direct combat support.[39][71]

Human Rights Watch wrote in 2000:

Of all the foreign powers involved in efforts to sustain and manipulate the ongoing fighting [in Afghanistan], Pakistan is distinguished both by the sweep of its objectives and the scale of its efforts, which include soliciting funding for the Taliban, bankrolling Taliban operations, providing diplomatic support as the Taliban's virtual emissaries abroad, arranging training for Taliban fighters, recruiting skilled and unskilled manpower to serve in Taliban armies, planning and directing offensives, providing and facilitating shipments of ammunition and fuel, and ... directly providing combat support.[71]

On August 1, 1997 the Taliban launched an attack on Sheberghan, the main military base of Abdul Rashid Dostum. Dostum has said the reason the attack was successful was that 1500 Pakistani commandos took part and that the Pakistani Air Force also gave support.[72]

In 1998 Iran accused Pakistani troops of war crimes at Bamiyan in Afghanistan and claimed that Pakistani warplanes had, in support of the Taliban, bombarded Afghanistan's last Shia stronghold.[73][74] The same year Russia said, Pakistan was responsible for the "military expansion" of the Taliban in northern Afghanistan by sending large numbers of Pakistani troops some of whom had subsequently been taken as prisoners by the anti-Taliban United Front.[75]

In 2000, the UN Security Council imposed an arms embargo against military support to the Taliban, with UN officials explicitly singling out Pakistan. The UN secretary-general implicitly criticized Pakistan for its military support and the Security Council stated it was "deeply distress[ed] over reports of involvement in the fighting, on the Taliban side, of thousands of non-Afghan nationals."[76] In July 2001, several countries including the United States, accused Pakistan of being "in violation of U.N. sanctions because of its military aid to the Taliban."[77] The Taliban also obtained financial resources from Pakistan. In 1997 alone, after the capture of Kabul by the Taliban, Pakistan gave $30 million in aid and a further $10 million for government wages.[78]

In 2000, British Intelligence reported that the ISI was taking an active role in several Al Qaeda training camps.[79] The ISI helped with the construction of training camps for both the Taliban and Al Qaeda.[79][80][81] From 1996 to 2001 the Al Qaeda of Osama Bin Laden and Ayman al-Zawahiri became a state within the Taliban state.[82] Bin Laden sent Arab and Central Asian Al-Qaeda militants to join the fight against the United Front, among them his Brigade 055.[82][83]

Anti-Taliban resistance

Abdul Rashid Dostum and his forces were defeated by the Taliban in 1998. Dostum subsequently went into exile. The only leader to remain in Afghanistan, and who was able to defend vast parts of his area against the Taliban, was Ahmad Shah Massoud. In the areas under his control Ahmad Shah Massoud set up democratic institutions and signed the Women's Rights Declaration.[84] In the area of Massoud, women and girls did not have to wear the Afghan burqa. They were allowed to work and to go to school. In at least two known instances, Massoud personally intervened against cases of forced marriage.[38] To Massoud there was reportedly nothing worse than treating a person like an object.[38] He stated:

It is our conviction and we believe that both men and women are created by the Almighty. Both have equal rights. Women can pursue an education, women can pursue a career, and women can play a role in society — just like men.[38]

Author Pepe Escobar wrote in Massoud: From Warrior to Statesman:

Massoud is adamant that in Afghanistan women have suffered oppression for generations. He says that 'the cultural environment of the country suffocates women. But the Taliban exacerbate this with oppression.' His most ambitious project is to shatter this cultural prejudice and so give more space, freedom and equality to women — they would have the same rights as men.[38]

While it was Massoud's stated conviction that men and women are equal and should enjoy the same rights, he also had to deal with Afghan traditions which he said would need a generation or more to overcome. In his opinion that could only be achieved through education.[38] Humayun Tandar, who took part as an Afghan diplomat in the 2001 International Conference on Afghanistan in Bonn, said that "strictures of language, ethnicity, region were [also] stifling for Massoud. That is why ... he wanted to create a unity which could surpass the situation in which we found ourselves and still find ourselves to this day."[38] This applied also to strictures of religion. Jean-José Puig describes how Massoud often led prayers before a meal or at times asked his fellow Muslims to lead the prayer but also did not hesitate to ask a Christian friend Jean-José Puig or the Jewish Princeton Professor Michael Barry: "Jean-José, we believe in the same God. Please, tell us the prayer before lunch or dinner in your own language."[38]

Human Rights Watch cites no human rights crimes for the forces under direct control of Massoud for the period from October 1996 until the assassination of Massoud in September 2001.[85] One million people fled the Taliban, many to the area of Massoud.[86][87] National Geographic concluded in its documentary "Inside the Taliban":

The only thing standing in the way of future Taliban massacres is Ahmad Shah Massoud.[70]

The Taliban repeatedly offered Massoud a position of power to make him stop his resistance. Massoud declined. He explained in one interview:

The Taliban say: "Come and accept the post of prime minister and be with us", and they would keep the highest office in the country, the presidentship. But for what price?! The difference between us concerns mainly our way of thinking about the very principles of the society and the state. We can not accept their conditions of compromise, or else we would have to give up the principles of modern democracy. We are fundamentally against the system called "the Emirate of Afghanistan".[88]

And in another:

There should be an Afghanistan where every Afghan finds himself or herself happy. And I think that can only be assured by democracy based on consensus.[89]

Massoud with his Proposals for Peace wanted to convince the Taliban to join a political process leading towards nationwide democratic elections in a foreseeable future.[88] Massoud also stated:

The Taliban are not a force to be considered invincible. They are distanced from the people now. They are weaker than in the past. There is only the assistance given by Pakistan, Osama bin Laden and other extremist groups that keep the Taliban on their feet. With a halt to that assistance, it is extremely difficult to survive.[89]

In early 2001 Massoud employed a new strategy of local military pressure and global political appeals.[90] Resentment was increasingly gathering against Taliban rule from the bottom of Afghan society including the Pashtun areas.[90] Massoud publicized their cause of "popular consensus, general elections and democracy" worldwide. At the same time he was very wary not to revive the failed Kabul government of the early 1990s.[90] In 1999, he began training police forces specifically to keep order and protect the civilian population, in case the United Front was successful.[38]

In early 2001 Ahmad Shah Massoud addressed the European Parliament in Brussels asking the international community to provide humanitarian help to the people of Afghanistan.[91] (Video on YouTube) He stated that the Taliban and Al Qaeda had introduced "a very wrong perception of Islam" and that without the support of Pakistan and Bin Laden the Taliban would not be able to sustain their military campaign for up to a year.[92] On this visit to Europe he also warned that his intelligence had gathered information about a large-scale attack on U.S. soil being imminent.[93][94] The president of the European Parliament, Nicole Fontaine, called him the "pole of liberty in Afghanistan".[95]

On September 9, 2001, Massoud, then aged 48, was the target of a suicide attack by two Arabs posing as journalists at Khwaja Bahauddin, in the Takhar Province of Afghanistan.[96][97] Massoud died in a helicopter taking him to a hospital. The funeral, though in a rather rural area, was attended by hundreds of thousands of mourning people.[98]

The assassination was not the first time Al-Qaeda, the Taliban, the Pakistani ISI, and before them the Soviet KGB, the Afghan Communist KHAD and Hekmatyar had tried to assassinate Massoud. He survived countless assassination attempts over a period of 26 years. The first attempt on Massoud's life was carried out by Hekmatyar and two Pakistani ISI agents in 1975, when Massoud was only 22 years old.[31] In early 2001, Al-Qaeda would-be assassins were captured by Massoud's forces while trying to enter his territory.[90]

9/11 connection

The assassination of Massoud is considered to have a strong connection to the September 11, 2001 attacks on the United States, which killed nearly 3000 people, and which appeared to be the terrorist attack that Massoud had warned against in his speech to the European Parliament several months earlier.[99]

John P. O'Neill was a counter-terrorism expert and the Assistant Director of the FBI until late 2001. He retired from the FBI and was offered the position of director of security at the World Trade Center (WTC). He took the job at the WTC two weeks before 9/11. On September 10, 2001, O'Neill allegedly told two of his friends, "We're due. And we're due for something big.... Some things have happened in Afghanistan. [referring to the assassination of Massoud] I don't like the way things are lining up in Afghanistan...I sense a shift, and I think things are going to happen...soon."[100] O'Neill died on September 11, 2001, when the South Tower collapsed.[100]

After the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, Massoud's United Front troops, with American air support, ousted the Taliban from power in Kabul in Operation Enduring Freedom. In November and December 2001, the United Front gained control of much of the country and played a crucial role in establishing the post-Taliban interim government of Hamid Karzai in late 2001.[101]

Islamic Republic and NATO

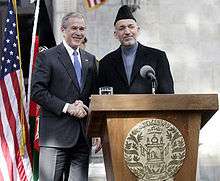

The US-led war in Afghanistan began on October 7, 2001, as Operation Enduring Freedom. It was designed to capture or kill Osama bin Laden and al-Qaeda militants, as well as replace the Taliban with a US-friendly government. The Bush Doctrine stated that, as policy, it would not distinguish between al-Qaeda and nations that harbor them.

Several Afghan leaders were invited to Germany in December 2001 for the UN sponsored Bonn Agreement, which was to restore stability and governance in their country. In the first step, the Afghan Transitional Administration was formed and was installed on December 22, 2001.[102] Chaired by Hamid Karzai, it numbered 30 leaders and included a Supreme Court, an Interim Administration, and a Special Independent Commission.

A loya jirga (grand assembly) was convened in June 2002 by former King Zahir Shah, who returned from exile after 29 years. Hamid Karzai was elected President for the two years in the jirga, in which the Afghan Interim Authority was also replaced with the Transitional Islamic State of Afghanistan (TISA). A constitutional loya jirga was held in December 2003, adopting the new 2004 constitution, with a presidential form of government and a bicameral legislature.[103] Karzai was elected in the 2004 presidential election followed by winning a second term in the 2009 presidential election. Both the 2005 and the 2010 parliamentary elections were also successful.

In the meantime, the reconstruction process of Afghanistan began in 2002. There are more than 14,000 reconstruction projects under way in Afghanistan, such as the Kajaki and the Salma Dam.[104] Many of these projects are being supervised by the Provincial Reconstruction Teams. The World Bank contribution is the multilateral Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund (ARTF), which was set up in 2002. It is financed by 24 international donor countries and has spent more than $1.37 billion as of 2007.[105] Approximately 30 billion dollars have been provided by the international community for the reconstruction of Afghanistan, most of it from the United States. In 2002, the world community allocated $4 billion at the Tokyo conference followed by another $4 billion in 2004. In February 2006, $10.5 billion were committed for Afghanistan at the London Conference[106] and $11 billion from the United States in early 2007. Despite these vast investments by the international community, the reconstruction effort's results have been mixed. Implementation of development projects at the district and sub-district level has been frequently marred by lack of coordination, knowledge of local conditions, and sound planning on the side of international donors as well as by corruption and inefficiency on the side of Afghan government officials. On the provincial and national level, projects such as the National Solidarity Programme, inter-provincial road construction, and the US-led revamping of rural health services have met with more success. As NATO prepares to withdraw the majority of remaining ISAF troops by the end of 2014, whether the Afghan government will be able to sustain the developmental gains made over the past 12 years, and to what extent international civilian aid organizations will be able to continue operations or refocus their efforts based on lessons learned, remains to be seen.

The UN Security Council established the International Security Assistance Force (ISAF) in December 2001 to provide basic security for the people of Afghanistan and assist the Karzai administration. Since 2002, the total number of ISAF and U.S. forces have climbed from 15,000 to 150,000. The majority of them belong to various branches of the United States Armed Forces, who are not only fighting the Taliban insurgency but also training the Afghan Armed Forces and Afghan National Police. They are scheduled to withdraw slowly until the end of 2014 but Vice President Joe Biden has proposed to retain an unknown number of U.S. military personnel after the 2014 deadline if the security situation required and the Afghan government and people desired.[107] Germany has announced that they will continue training Afghan police recruits after the 2014 withdrawal date for military troops.[108]

NATO and Afghan troops led many offensives against the Taliban in this period. By 2009, a Taliban-led shadow government began to form, complete with their own version of mediation court.[109] In 2010, U.S. President Barack Obama deployed an additional 30,000 soldiers over a period of six months and proposed that he would begin troop withdrawals by 2012. At the 2010 International Conference on Afghanistan in London, Afghan President Hamid Karzai said he intended to reach out to the Taliban leadership (including Mullah Omar, Sirajuddin Haqqani and Gulbuddin Hekmatyar). Supported by senior U.S. officials Karzai called on the group's leadership to take part in a loya jirga meeting to initiate peace talks. According to The Wall Street Journal, these steps were initially reciprocated with an intensification of bombings, assassinations and ambushes.[110]

Many Afghan groups (including the former intelligence chief Amrullah Saleh and opposition leader Dr. Abdullah Abdullah) believe that Karzai's plan aims to appease the insurgents' senior leadership at the cost of the democratic constitution, the democratic process and progress in the field of human rights, especially women's rights.[111] Dr. Abdullah stated:

I should say that Taliban are not fighting in order to be accommodated. They are fighting in order to bring the state down. So it's a futile exercise, and it's just misleading. ... There are groups that will fight to the death. Whether we like to talk to them or we don't like to talk to them, they will continue to fight. So, for them, I don't think that we have a way forward with talks or negotiations or contacts or anything as such. Then we have to be prepared to tackle and deal with them militarily. In terms of the Taliban on the ground, there are lots of possibilities and opportunities that with the help of the people in different parts of the country, we can attract them to the peace process; provided, we create a favorable environment on this side of the line. At the moment, the people are leaving support for the government because of corruption. So that expectation is also not realistic at this stage.[112]

According to a report by the United Nations, the Taliban were responsible for 76% of civilian casualties in 2009.[113] Afghanistan is currently struggling to rebuild itself while dealing with the results of 30 years of war, corruption among high-level politicians and the ongoing Taliban insurgency which according to different scientific institutes such as the London School of Economics, senior international officials, such as former United States Chairman of the Joint Chief of Staff Admrial Mike Mullen, believe the Taliban is backed by Pakistan's intelligence service.[114][115]

At the end of July 2010, the Netherlands became the first NATO ally to end its combat mission in Afghanistan after 4 years military deployment including the most intense period of hostilities. They withdrew 1,900 troops. The Atlantic Council described the decision as "politically significant because it comes at a time of rising casualties and growing doubts about the war."[116] Canada withdrew troops in 2011, but about 900 were left to train Afghani soldiers.[117][118]

In February 2012, a small number of American service members burned several copies of the Quran. Some Afghans responded with massive demonstrations and riots in Kabul and other areas. Assailants killed several American military personnel, including two officers in the Interior Ministry building following this event.

On March 11, 2012, an American soldier, Robert Bales, killed 16 civilians in the Kandahar massacre.

According to ISAF there were about 120,000 NATO-led troops in Afghanistan per December 2012, of which 66,000 were US troops and 9,000 British. The rest were from 48 different countries. A process of handing over power to local forces has started and according to plans a majority of international troops will leave in 2014.[119]

On November 24, 2013, President Karzai made a Loya jirga and put a ban on NATO house raids. This ban was put in place, and NATO soldiers were instructed to obey and follow this ban. In December 2013, a house raid in Zabul Province was exceptionally carried out by two NATO soldiers. Karzai condemned this in a highly publicised speech. On January 3, 2014 a bomb was heard by NATO soldiers in a base in Kabul; there were no reported casualties or injuries. The day after, a bomb hit a US military base in Kabul and killed one US citizen. The bomb was planted by the Taliban and the American service member was the first combat casualty in Afghanistan in that year. The Taliban immediately claimed responsibility for the attack.

On May 1, 2015 the media reported about a scheduled meeting in Qatar between Taliban insurgents and peacemakers, including the Afghan President, about ending the war.[120][121][122]

See also

Bibliography

- Hillenbrand, Carole (2015), Islam: A New Historical Introduction, London: Thames & Hudson Ltd, ISBN 978-0-500-11027-0

References

- Isby, David C. (15 June 1986). Russia's War in Afghanistan. ISBN 9780850456912. Archived from the original on 6 April 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Giustozzi, Antonio (2000). War, Politics and Society in Afghanistan, 1978–1992. ISBN 9781850653967. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "Afghanistan : Demographic Consequences of War : 1978–1987" (PDF). Nonel.pu.ru. Archived (PDF) from the original on 10 October 2017. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- "Life under Taliban cuts two ways". The Christian Science Monitor. 20 September 2001. Archived from the original on 14 June 2006. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "Human Costs of War: Direct War Death in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Pakistan : October 2001 – February 2013" (PDF). Costsofwar.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2013. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Apart from Taliban, since 2001 war has also involved other groups including al-Qaeda, Haqqani network, Hezb-e Islami Gulbuddin and ISIS-K

- Bearak, Barry (24 July 2007). "Mohammad Zahir Shah, Last Afghan King, Dies at 92". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017.

- Judah, Tim (23 September 2001). "Profile: Mohamed Zahir Shah". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 25 August 2013. Retrieved 18 March 2008.

- Katzman, Kenneth (30 March 2012). "Afghanistan: Politics, Elections, and Government Performance" (PDF). Congressional Research Service. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 September 2015.

- Neamatollah Nojumi (2002). The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass Mobilization, Civil War, and the Future of the Region (2002 1st ed.). Palgrave, New York. pp. 38–42.

- Neamatollah Nojumi (2002). The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass Mobilization, Civil War, and the Future of the Region (2002 1st ed.). Palgrave, New York. p. 39.

- Neamatollah Nojumi (2002). The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass Mobilization, Civil War, and the Future of the Region (2002 1st ed.). Palgrave, New York. p. 41.

- Neamatollah Nojumi (2002). The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass Mobilization, Civil War, and the Future of the Region (2002 1st ed.). Palgrave, New York. p. 42.

- "World: Analysis Afghanistan: 20 years of bloodshed". BBC News. 26 April 1998. Archived from the original on 16 October 2009. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- Soldiers of God: With Islamic Warriors in Afghanistan and Pakistan Archived 2016-01-31 at the Wayback Machine by Robert D. Kaplan. Vintage, 2001. ISBN 1-4000-3025-0 p.115

- Hillenbrand 2015, p. 284

- Svetlana Savranskaya. "Volume II: Afghanistan: Lessons from the Last War". The National Security Archive. Archived from the original on 12 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- "How Not to End a War". The Washington Post. 17 July 2007. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2009.

- "Russia marks Afghanistan retreat". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 9 March 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- Kakar, Mohammed (1997-03-03). The Soviet Invasion and the Afghan Response, 1979–1982. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20893-3. Archived from the original on 2017-01-06. Retrieved 2017-01-07.

The Afghans are among the latest victims of genocide by a superpower. Large numbers of Afghans were killed to suppress resistance to the army of the Soviet Union, which wished to vindicate its client regime and realize its goal in Afghanistan.

- Klass, Rosanne (1994). The Widening Circle of Genocide. Transaction Publishers. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-4128-3965-5.

During the intervening fourteen years of Communist rule, an estimated 1.5 to 2 million Afghan civilians were killed by Soviet forces and their proxies- the four Communist regimes in Kabul, and the East Germans, Bulgarians, Czechs, Cubans, Palestinians, Indians and others who assisted them. These were not battle casualties or the unavoidable civilian victims of warfare. Soviet and local Communist forces seldom attacked the scattered guerilla bands of the Afghan Resistance except, in a few strategic locales like the Panjsher valley. Instead they deliberately targeted the civilian population, primarily in the rural areas.

- Reisman, W. Michael; Norchi, Charles H. "Genocide and the Soviet Occupation of Afghanistan" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 October 2016. Retrieved 7 January 2017.

According to widely reported accounts, substantial programmes of depopulation have been conducted in these Afghan provinces: Ghazni, Nagarhar, Lagham, Qandahar, Zabul, Badakhshan, Lowgar, Paktia, Paktika and Kunar...There is considerable evidence that genocide has been committed against the Afghan people by the combined forces of the Democratic Republic of Afghanistan and the Soviet Union.

- Haroon, Sana (2008). "The Rise of Deobandi Islam in the North-West Frontier Province and Its Implications in Colonial India and Pakistan 1914–1996". Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society. 18 (1): 66–67. JSTOR 27755911.

- "1988: USSR pledges to leave Afghanistan". BBC News. 14 April 1988. Archived from the original on 17 April 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- "Charlie Rose March 26, 2001". CBS. 2001. Archived from the original on April 17, 2011.

- "He would have found Bin Laden". CNN. 27 May 2009. Archived from the original on 28 June 2011.

- Tomsen, Peter (2011). Wars of Afghanistan. PublicAffairs. pp. 405–408. ISBN 978-1-58648-763-8.

- "Blood-Stained Hands, Past Atrocities in Kabul and Afghanistan's Legacy of Impunity". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 2009-03-14. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- Neamatollah Nojumi (2002). The Rise of the Taliban in Afghanistan: Mass Mobilization, Civil War, and the Future of the Region (2002 1st ed.). Palgrave, New York.

- Amin Saikal (2004-11-13). Modern Afghanistan: A History of Struggle and Survival (2006 1st ed.). I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd., London New York. p. 352. ISBN 1-85043-437-9.

- GUTMAN, Roy (2008): How We Missed the Story: Osama Bin Laden, the Taliban and the Hijacking of Afghanistan, Endowment of the United States Institute of Peace, 1st ed., Washington D.C.

- "The September 11 Sourcebooks Volume VII: The Taliban File". George Washington University. 2003. Archived from the original on 2013-10-31. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

- "Casting Shadows: War Crimes and Crimes against Humanity: 1978–2001" (PDF). Afghanistan Justice Project. 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-10-04. Retrieved 2011-03-23.

- "II. BACKGROUND". Human Rights Watch. Archived from the original on 2008-11-02. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- Matinuddin, Kamal, The Taliban Phenomenon, Afghanistan 1994–1997, Oxford University Press, (1999), pp.25–6

- "Document – Afghanistan: Further information on fear for safety and new concern: deliberate and arbitrary killings: Civilians in Kabul – Amnesty International". Amnesty.org. Archived from the original on 3 April 2015. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "Afghanistan: escalation of indiscriminate shelling in Kabul". International Committee of the Red Cross. 1995. Archived from the original on 2011-05-10. Retrieved 2010-12-22.

- Marcela Grad. Massoud: An Intimate Portrait of the Legendary Afghan Leader (March 1, 2009 ed.). Webster University Press. p. 310.

- "Documents Detail Years of Pakistani Support for Taliban, Extremists". George Washington University. 2007. Archived from the original on 2008-07-08. Retrieved 2010-12-22.

- Coll, Ghost Wars (New York: Penguin, 2005), 14.

- "The Taliban's War on Women. A Health and Human Rights Crisis in Afghanistan" (PDF). Physicians for Human Rights. 1998. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2007-07-02. Retrieved 2010-12-22.

- Video on YouTube

- Newsday (October 2001). "Taliban massacres outlined for UN". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 2011-09-16.

- Newsday (2001). "Confidential UN report details mass killings of civilian villagers". newsday.org. Archived from the original on November 18, 2002. Retrieved October 12, 2001.

- "Afghanistan: Situation in, or around, Aqcha (Jawzjan province) including predominant tribal/ethnic group and who is currently in control". UNHCR. February 1999. Archived from the original on 2011-05-10.

- Human Rights Watch (November 1998). "INCITEMENT OF VIOLENCE AGAINST HAZARAS BY GOVERNOR NIAZI". AFGHANISTAN: THE MASSACRE IN MAZAR-I SHARIF. hrw.org. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved December 27, 2007.

- "Iranian military exercises draw warning from Afghanistan". CNN News. 1997-08-31. Archived from the original on December 11, 2008.

- "Taliban threatens retaliation if Iran strikes". CNN. 1997-09-15. Archived from the original on 2009-04-23. Retrieved 2009-03-14.

- Ahmed Rashid (2001-09-11). "Afghanistan resistance leader feared dead in blast". Telegraph. London. Archived from the original on 2013-11-08. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- Nasir, Abbas (18 August 2015). "The legacy of Pakistan's loved and loathed Hamid Gul". Al Jazeera. Archived from the original on 3 January 2017. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

His commitment to jihad – to an Islamic revolution transcending national boundaries, was such that he dreamed one day the "green Islamic flag" would flutter not just over Pakistan and Afghanistan, but also over territories represented by the (former Soviet Union) Central Asian republics. After the Soviet withdrawal from Afghanistan, as the director-general of the Pakistan's intelligence organisation, Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) directorate, an impatient Gul wanted to establish a government of the so-called Mujahideen on Afghan soil. He then ordered an assault using non-state actors on Jalalabad, the first major urban centre across the Khyber Pass from Pakistan, with the aim capturing it and declaring it as the seat of the new administration.

- Shaffer, Brenda (2006). The Limits of Culture: Islam and Foreign Policy. MIT Press. p. 267. ISBN 978-0-262-69321-9.

Pakistani involvement in creating the movement is seen as central

- Forsythe, David P. (2009). Encyclopedia of human rights (Volume 1 ed.). Oxford University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-19-533402-9.

In 1994 the Taliban was created, funded and inspired by Pakistan

- Gardner, Hall (2007). American global strategy and the 'war on terrorism'. Ashgate. p. 59. ISBN 978-0-7546-7094-0.

- Jones, Owen Bennett (2003). Pakistan: eye of the storm. Yale University Press. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-300-15475-7.

The ISI's undemocratic tendencies are not restricted to its interference in the electoral process. The organisation also played a major role in creating the Taliban movement.

- Randal, Jonathan (2005). Osama: The Making of a Terrorist. I.B.Tauris. p. 26. ISBN 978-1-84511-117-5.

Pakistan had all but invented the Taliban, the so-called Koranic students

- Peiman, Hooman (2003). Falling Terrorism and Rising Conflicts. Greenwood. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-275-97857-0.

Pakistan was the main supporter of the Taliban since its military intelligence, the Inter-Services Intelligence (ISI) formed the group in 1994

- Hilali, A. Z. (2005). US-Pakistan relationship: Soviet invasion of Afghanistan. Ashgate. p. 248. ISBN 978-0-7546-4220-6.

- Rumer, Boris Z. (2002). Central Asia: a gathering storm?. M.E. Sharpe. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-7656-0866-6.

- Pape, Robert A (2010). Cutting the Fuse: The Explosion of Global Suicide Terrorism and How to Stop It. University of Chicago Press. pp. 140–141. ISBN 978-0-226-64560-5.

- Harf, James E.; Mark Owen Lombard (2004). The Unfolding Legacy of 9/11. University Press of America. p. 122. ISBN 978-0-7618-3009-2.

- Hinnells, John R. (2006). Religion and violence in South Asia: theory and practice. Routledge. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-415-37290-9.

- Boase, Roger (2010). Islam and Global Dialogue: Religious Pluralism and the Pursuit of Peace. Ashgate. p. 85. ISBN 978-1-4094-0344-9.

Pakistan's Inter-Services Intelligence agency used the students from these madrassas, the Taliban, to create a favourable regime in Afghanistan

- Armajani, Jon (2012). Modern Islamist Movements: History, Religion, and Politics. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 48. ISBN 978-1-4051-1742-5.

- Bayo, Ronald H. (2011). Multicultural America: An Encyclopedia of the Newest Americans. Greenwood. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-313-35786-2.

- Goodson, Larry P. (2002). Afghanistan's Endless War: State Failure, Regional Politics and the Rise of the Taliban. University of Washington Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-295-98111-6.

Pakistani support for the Taliban included direct and indirect military involvement, logistical support

- Maley, William (2009). The Afghanistan wars. Palgrave Macmillan. p. 288. ISBN 978-0-230-21313-5.

- Tomsen, Peter (2011). Wars of Afghanistan. PublicAffairs. p. 322. ISBN 978-1-58648-763-8.

- Edward Girardet. Killing the Cranes: A Reporter's Journey Through Three Decades of War in Afghanistan (August 3, 2011 ed.). Chelsea Green Publishing. p. 416.

- Rashid 2000, p. 91

- "Inside the Taliban". National Geographic Society. 2007. Archived from the original on 2015-12-16. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- "Pakistan's support of the taliban". Human Rights Watch. 2000. Archived from the original on 2010-06-15.

- Clements, Frank (2003). Conflict in Afghanistan: a historical encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 54. ISBN 978-1-85109-402-8.

- Schmetzer, Uli (14 September 1998). "Iran Raises Anti-pakistan Outcry". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

KARACHI, Pakistan — Iran, which has amassed 200,000 troops on the border with Afghanistan, accused Pakistan on Sunday of sending warplanes to strafe and bombard Afghanistan's last Shiite stronghold, which fell hours earlier to the Taliban, the Sunni militia now controlling the central Asian country.

- Constable, Pamela (16 September 1998). "Afghanistan: Arena For a New Rivalry". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 5 February 2017. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

Taliban officials accused Iran of providing military support to the opposition forces; Tehran radio accused Pakistan of sending its air force to bomb the city in support of the Taliban's advance and said Iran was holding Pakistan responsible for what it termed war crimes at Bamiyan. Pakistan has denied that accusation and previous allegations of direct involvement in the Afghan conflict. Also fueling the volatile situation are ethnic and religious rivalries between the Taliban, who are Sunni Muslims of Afghanistan's dominant Pashtun ethnic group, and the opposition factions, many of which represent other ethnic groups or include Shiite Muslims. Iran, a Shiite Muslim state, has a strong interest in promoting that sect; Pakistan, one of the Taliban's few international allies, is about 80 percent Sunni.

- "Pak involved in Taliban offensive – Russia". Express India. 1998. Archived from the original on 2005-01-28.

- "Afghanistan & the United Nations". United Nations. 2012. Archived from the original on 2013-10-31.

- "U.S. presses for bin Laden's ejection". The Washington Times. 2001. Archived from the original on 2013-05-11.

- Byman, Daniel (2005). Deadly connections: states that sponsor terrorism. Cambridge University Press. p. 195. ISBN 978-0-521-83973-0.

- Atkins, Stephen E. (2011). The 9/11 Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 540. ISBN 978-1-59884-921-9.

- Litwak, Robert (2007). Regime change: U.S. strategy through the prism of 9/11. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 309. ISBN 978-0-8018-8642-3.

- McGrath, Kevin (2011). Confronting Al-Qaeda. Naval Institute Press. p. 138. ISBN 978-1-59114-503-5.

the Pakistani military's Inter-services Intelligence Directorate (IsI) provided assistance to the Taliban, to include its military and al Qaeda–related terrorist training camps

- "Book review: The inside track on Afghan wars by Khaled Ahmed". Daily Times. 2008. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013.

- "Brigade 055". CNN. Archived from the original on 2015-07-19. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- Marcela Grad. Massoud: An Intimate Portrait of the Legendary Afghan Leader (March 1, 2009 ed.). Webster University Press. p. 310.

- "Human Rights Watch Backgrounder, October 2001". Human Rights Watch. 2001. Archived from the original on 2010-10-19. Retrieved 2016-12-04.

- "Inside the Taliban". National Geographic. 2007. Archived from the original on 2015-12-16. Retrieved 2015-12-13.

- "Inside the Taliban". National Geographic. 2007. Archived from the original on September 29, 2008.

- "The Last Interview with Ahmad Shah Massoud". Piotr Balcerowicz. 2001. Archived from the original on 2006-09-25. Retrieved 2013-11-23.

- "The man who would have led Afghanistan". St. Petersburg Times. 2002. Archived from the original on 2010-08-13. Retrieved 2010-08-30.

- Steve Coll (2005). Ghost Wars: The Secret History of the CIA, Afghanistan, and Bin Laden, from the Soviet Invasion to September 10, 2001 (February 23, 2004 ed.). Penguin Press HC. p. 720.

- "Massoud in the European Parliament 2001". EU media. 2001. Archived from the original on 2014-02-25. Retrieved 2014-04-05.

- "Massoud in the European Parliament 2001". EU media. 2001. Archived from the original on 2015-07-12. Retrieved 2014-04-05.

- "Secret document" (PDF). Gwu.edu. Archived (PDF) from the original on 17 June 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Boettcher, Mike (November 6, 2003). "How much did Afghan leader know?". CNN.com. Archived from the original on September 16, 2010. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- "see video". Youtube.com. March 5, 2001. Archived from the original on July 12, 2015. Retrieved October 31, 2010.

- "Taliban Foe Hurt and Aide Killed by Bomb". Afghanistan: Nytimes.com. September 10, 2001. Archived from the original on February 5, 2013. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- Burns, John F. (September 9, 2002). "THREATS AND RESPONSES: ASSASSINATION; Afghans, Too, Mark a Day of Disaster: A Hero Was Lost". Afghanistan: Nytimes.com. Archived from the original on February 17, 2011. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- Ahmad Shah Massoud Sad Day Part 2 on YouTube

- Mike Boettcher; Henry Schuster. "How much did Afghan leader know? - Nov. 6, 2003". www.cnn.com. Archived from the original on 2014-12-23. Retrieved 2018-05-20.

- "The Man Who Knew". PBS. 2002. Archived from the original on 2017-09-03. Retrieved 2017-09-18.

- The Far East and Australasia 2003 (34th ed.). London: Europa. 2002. pp. xix. ISBN 1-85743-133-2. OCLC 59468141.

- "UN factsheet on Bonn Agreement" (PDF). United Nations. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 March 2009. Retrieved 15 March 2009.

- "Afghan MPs hold landmark session". BBC News. 2005-12-19. Archived from the original on 2009-01-03. Retrieved 2009-03-15.

- "Afghanistan: NATO Pleased With Offensive, But Goals Still Unmet". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Archived from the original on 9 July 2008. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- "Afghanistan Reconstruction Trust Fund". World Bank. Archived from the original on 2 February 2009. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- "Government to have greater control over aid pledged in London". IRIN Asia. 2004-09-27. Archived from the original on 2006-11-29. Retrieved 2009-03-13.

- https://news.yahoo.com/s/afp/20110111/wl_sthasia_afp/afghanistanunrestusbiden_20110111142049. Retrieved October 14, 2010. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - "Berlin to train Afghan police even after security handover". DW.DE. Archived from the original on 26 September 2010. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Witte, Griff (2009-12-08). "Taliban shadow officials offer concrete alternative". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 2011-05-16. Retrieved 2010-03-30.

- Trofimov, Yaroslav (2010-09-11). "Karzai Divides Afghanistan in Reaching Out to Taliban". The "Wall Street Journal". Archived from the original on 12 September 2010. Retrieved 2010-09-11.

- "Karzai's Taleban talks raise spectre of civil war warns former spy chief". The Scotsman. Edinburgh. 2010-09-30. Archived from the original on 2010-12-03.

- "Abdullah Abdullah: Talks With Taliban Futile". National Public Radio (NPR). 2010-10-22. Archived from the original on 2018-09-21.

- "UN: Taliban Responsible for 76% of Deaths in Afghanistan". The Weekly Standard. 2010-08-10. Archived from the original on 2011-01-02.

- "Pakistan Accused of Helping Taliban". ABC News. 2008-07-31. Archived from the original on 2013-12-21. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- Crilly, Rob; Spillius, Alex (26 July 2010). "Wikileaks: Pakistan accused of helping Taliban in Afghanistan attacks". London: U.K. Telegraph. Archived from the original on 29 January 2014. Retrieved 28 September 2010.

- "Dutch become 1st NATO member to quit Afghanistan". Atlantic Council. August 1, 2010. Archived from the original on December 24, 2011. Retrieved March 12, 2012.

- Theophilos Argitis: Canada’s Harper Makes Afghanistan Stop to Mark End of Military Mission Archived 2014-02-22 at the Wayback Machine Bloomberg.com, 31 May 2011

- Brian Stewart:Let's be clear, Canada is still at war in Afghanistan Archived 2013-02-18 at the Wayback Machine CBC News, November 2, 2011

- "BBC News – Q&A: Foreign forces in Afghanistan". BBC News. Archived from the original on 14 October 2014. Retrieved 18 October 2014.

- Rafiq Sharzad (1 May 2015). "Afghan delegation to meet with Taliban in Qatar – officials". Reuters. Archived from the original on 23 August 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- "Afghan delegation heads to Qatar for talks with the Taliban". The Guardian. 2 May 2015. Archived from the original on 7 August 2015. Retrieved 3 September 2015.

- "Afghan delegation to meet with Taleban in Qatar". Arab News. 2 May 2015. Archived from the original on 2 May 2015. Retrieved 2 May 2015.

Further reading

- Collins, Joseph J. (2011). Understanding War in Afghanistan (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Defense University Press. ISBN 978-1-78039-924-9.

- George Friedman (June 29, 2010). "The 30-Year War in Afghanistan". Geopolitical Weekly. Stratfor.

- Chiovenda, Andrea, and Melissa Chiovenda. "The specter of the “arrivant”: hauntology of an interethnic conflict in Afghanistan." Asian Anthropology 17.3 (2018): 165-184.

External links

- Afghanistan Conflict Monitor

- Backgrounder on Afghanistan: History of the War October 2001

- Ending Afghanistan’s Civil by James Dobbins, The RAND Corporation, Testimony presented before the House Armed Services Committee on January 30, 2007

- Fueling Afghanistan's War-Press Backgrounder

- More information on Post-Conflict Reconstruction from the Center for Strategic and International Studies

.png)