Szmalcownik

Szmalcownik (Polish pronunciation: [ʂmalˈtsɔvɲik]); in English, also spelled shmaltsovnik) is a pejorative Polish slang expression that originated during the Holocaust in Poland in World War II and refers to a person who blackmailed Jews who were in hiding, or who blackmailed Poles who protected Jews during the German occupation.

Etymology

The term originated in the German word Schmalz (Polish phonetic spelling: szmalc, literally meaning "lard") and indicated the blackmailer's financial motive.

History

Extent and effects

The damage that these criminals did was substantial.[1] Gunnar S. Paulsson estimates that the total number of szmalcowniks in Warsaw alone was "as high as 3–4 thousand."[2] Many szmalcowniks came from the "dregs of society" – either organized or petty criminals. Some were also on the Gestapo's payroll. They included individuals of all ethnicities found in Poland: ethnic Poles and members of the German, Ukrainian, and Lithuanian minorities, and in extreme cases, even Jews themselves.[1]

Most were interested in money. By stripping Jews of assets needed for food and bribes, harassing rescuers, raising the overall level of insecurity, and forcing hidden Jews to seek safer accommodations, blackmailers added substantially to the danger that Jews and Poles who hid them (endangered by the German-imposed death penalty) faced and increased their chances of getting caught and killed.[1] At the beginning of the German occupation, szmalcowniks were satisfied with a few hundred zlotys in extortion, but after the death penalty was introduced for hiding Jews, the sums rose to several hundred thousand zlotych.

Countermeasures

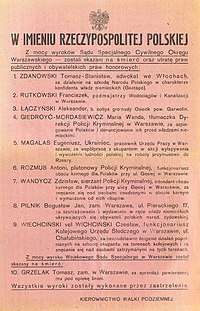

"Every Pole who cooperates with their murderous action, whether blackmailing or denouncing Jews, exploiting their cruel situation or participating in looting, commits a serious crime against the laws of the Republic of Poland and will be immediately punished ..."[3]

The Polish Secret State considered szmalcownictwo an act of collaboration with the occupying Germans. The Home Army (Armia Krajowa) punished it with death as a criminal act of treason.[3] Blackmailers were sentenced to death by Polish Underground Special Courts for crimes perpetrated against Polish citizens. A decree of 31 August 1944 of Polski Komitet Wyzwolenia Narodowego (the Polish Committee of National Liberation) also condemned such acts as collaboration with Germany. This decree remains valid law in Poland, and anyone convicted of szmalcownictwo during the war may face life imprisonment.

Approximately 30% of the Special Courts executions in Warsaw were of szmalcowniks.[4]

Starting summer of 1943 the Home Army started carrying out death sentences for szmalcowniks in Warsaw.[5]

According to Władysław Bartoszewski, despite the fact that the Home Army carried out more death sentences on blackmailers than any other resistance organization in occupied Europe, these death sentences did not have a significant effect on the scale of blackmail and denunciation because of the difficulty of tracking down extortionists.[6] Joanna Drzewieniecki however cites two accounts from the diaries of the Warsaw Jews in which the subjects themselves believed that those executions deterred at least some of the szmalcowniks.[5]

The Germans sometimes also treated szmalcowniks as criminals and punished them. The reason was that szmalcowniks also bribed German officials and police: after a rich Jew had been denounced, the szmalcownik and corrupt German shared the loot.

References

- Irene Tomaszewski; Tecia Werbowski (2010). Code Name Żegota: Rescuing Jews in Occupied Poland, 1942-1945 : the Most Dangerous Conspiracy in Wartime Europe. ABC-CLIO. p. 70. ISBN 978-0-313-38391-5.

- Biuletyn IPN 3 (12)/2013, p. 5, Instytut Pamięci Narodowej

- Żydzi polscy, zeszyt 24, "Sprawiedliwi wśród narodów" str. 11 artykuł "Śmierć dla szmalcowników" dodatek do Rzeczpospolitej z 23 września 2008

- Joshua D. Zimmerman (5 June 2015). The Polish Underground and the Jews, 1939–1945. Cambridge University Press. pp. 414–415. ISBN 978-1-107-01426-8.

- Joanna Drzewieniecki (30 November 2019). Dance with Death: A Holistic View of Saving Polish Jews during the Holocaust. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 256–257. ISBN 978-0-7618-7167-5.

- Andrzej Kunert: Żegota. Rada Pomocy Żydom 1942 – 1945. Warszawa: 2002, s. 34. Cytat: – Andrzej Friszke: Czy skala wyroków śmierci wydawanych w tych sprawach przez sądy Polski Podziemnej była na tyle znaczna, by mogła odstraszyć szmalcowników? – Władysław Bartoszewski: Nie, ale to była bardzo trudna sprawa. Mimo że w żadnym kraju okupowanej Europy podziemie nie wydało tylu wyroków, co u nas, to jednak trzeba zauważyć, że była to sprawa wyjątkowo trudna. Jak wytropić szmalcownika? Muszą być grupy, które obserwują i łapią. Gdzie? Na ulicy. I na gorącym uczynku. Bo przecież ofiara szantażu nigdy go nie znajdzie..

Further reading

- Jan, Grabowski (2004). "Ja tego żyda znam!": szantażowanie żydów w Warszawie, 1939–1943 / "I know this Jew!": Blackmailing of the Jews in Warsaw 1939–1945 (in Polish). Warsaw, Poland: Wydawn. IFiS PAN : Centrum Badań nad Zagładą Żydów. ISBN 83-7388-058-5. OCLC 60174481.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Szmalcownik. |