Yugambeh people

| Yugambeh, Ngarangwal, Nganduwal, Mibin/Miban, Danggan Balun(Five Rivers) | |

|---|---|

| Total population | |

| ~10,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Yugambeh language | |

| Religion | |

| Dreaming, Christianity |

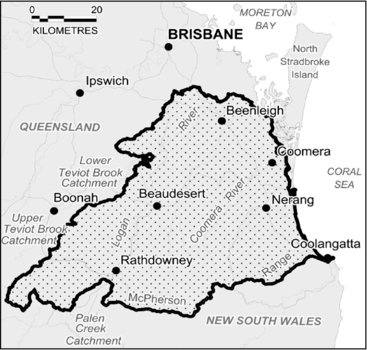

The Yugambeh (Yugambeh: Miban) are a group of Australian Aboriginal clans whose ancestors all spoke one or more dialects of the Yugambeh Language. Their traditional lands are located in south-east Queensland and north-east New South Wales, now within the Logan City, Gold Coast, Scenic Rim, and Tweed City regions.

Name, and etymology

Their ethnonym in the Yugambeh language derives from their word for "no", namely yukum, reflecting a widespread practice in aboriginal languages to identify a tribe by the word they used for a negative.[1] Language speakers use the word Miban which means "Man", "Human", "Wedge-Tailed Eagle"[lower-alpha 1] and is the preferred endonym for the people. The Kombumerri Corporation for Aboriginal Culture prefers not to use the generic umbrella term "Bundjalung", as opposed to Yugambeh, to describe themselves or language.[3] They call their language Mibanah meaning "of man", "of human", "of eagle" (the -Nah suffix forming the genitive of the word "Miban").

Language

The Yugambeh language is also known as the Tweed-Albert language, a dialect cluster of the wider Bandjalangic branch of the Pama–Nyungan language family.[4] At the 2016 Census, 22 people reported being speakers of the language. This was the first census where Yugambeh was included in the Australian Standard Classification of Languages as Yugambeh (8965).[5]

Dialects

The Tweed-Albert languages are split into three major dialect groups:

- Ngarangwal This was spoken between the Logan River and Point Danger,[6] and divided into a dialect employed between the Coomera and Logan rivers, and another between the Nerang and the Tweed, which had a 75% overlap with Nganduwal.[7] Crowley originally called this dialect Gold Coast, but the term Ngarangwal is often used today. This term was given by informants at Woodenbong in the 40s, who maintained however that it was a dialect of Bundjalung and not mutually intelligible with Yugambeh.[lower-alpha 2]

- Yugambeh (Proper)

- Nganduwal/Ngandowul (Livingstone gives this as the name of the dialect spoken on the Tweed, calling it a "sister dialect" of his Minyung which was spoken at Byron Bay and on the Brunswick River [the Tweed people referred to this language as Ngendu]. Norman Tindale also includes Nganduwal as an alternative name of his distinct Minyungbal tribe from Byron Bay.[9][10][11])

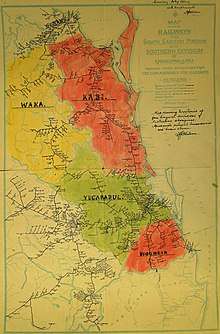

Country

The Yugambeh live within the Logan, Albert, Coomera, Nerang, and Tweed River basins.[10] Norman Tindale estimated their territorial reach as extending over roughly 1,200 square miles (3,100 km2), along the Logan River from Rathdowney to its mouth, and running south as far as the vicinity of Southport. Their western frontier lay around Boonah and the slopes of the Great Dividing Range.[12]

The Yuggera are to their west and north, the Quandamooka to their north-east (North Stradbroke and Moreton Island), the Githabul to their south-west, and the Bundjalung to their south.

Dreaming

The Three Brothers

In Yugambeh tradition, part of a larger story which is conserved among the neighbouring Minyungbal, the people descend from one of three brothers, Yarberri or Jabreen who travelled to the north and established the sacred site of Jebbribillum, the point at which he emerged from the waters onto the land.[13] The Legend of the Three Brothers is used to explain the kinship bonds that extend through the Yugambeh-Bundjalung language groups, one Yugambeh descendant writing:

"These bonds between Bundjalung and Yugambeh people are revealed through geneaology, and are evident in our common language dialects. Our legends unite us."

"Yugambeh people are the descendants of the brother Yarberri who travelled to the north. In Yugambeh legend he is known as Jabreen. Jabreen created his homeland by forming the mountains, the river systems and the flora and fauna. The people grew out of this evironment."

"Jabreen created the site known as Jebbribillum when he came out of the water onto the land. As he picked up his fighting waddy, the land and water formed into the shape of a rocky outcrop (Little Burleigh). This was the site where people gathered to learn and to share resources created by Jabreen. The ceremony held at this site became known as the Bora and symbolised the initiation of life. Through the ceremony, people learned to care for the land and their role was to preserve its integrity."[14]

The Great Battle

The Yugambeh have a tradition of a great battle between the creatures of the sky, land, and sea that took place at the mouth of the Logan river; this battle resulted in the creation of many landforms and rivers across the region. W.E. Hanlon recorded a version of this story in his reminiscences, which he titled "The Genesis of Pimpama Island":

In the old days "plenty long before whiteman bin come-up" (the legend runs), all that part of Moreton Bay, from Doogurrumburrum (Honeycomb), now Rocky Point, at the mouth of the Logan River, to Kanaipa (Ironbark spear) was the theatre of a titanic war between all the denizens of the land, the air, and the water then inhabiting that region. In those times the country bordering on this watery tract was high and dry, not like it is now, all swamps and marshes - and mosquitos. The real reason of this epic conflict is obscure, but it is generally supposed that the three main divisions of animal life - terrestrial, aerial, and aquatic - fought, triangularly, for supremacy; birds, flying foxes, sharks, purooises, "goannas", snakes, etc., all participated in the strife.

Yowgurra, the goanna, was early in the fray, armed with a spear; but, just as he joined in the melee, Boggaban, the sparrow hawk, swooped down and snatched the spear (juan) out of the grasp of Yowgurra. With this in its hands, it flew over the water and drove the spear into the back of a porpoise that just at that moment exposed itself. The porpoise, with a spear sticking it its back, exerted itself to a mighty blast and blew the weapon out; but there ensued such an incessant torrent of mingled blood and water from the spear wound that all the neighbouring territory became inundated, of channels and creeks of that portion of the Bay, and from this cause originated Pimpama Island Tajingpa (the well), Yawulpah (wasp), Wahgumpa (turkey), Coombabah (a pocket of land), etc., all great areas of swampy country.[15]

History

Pre-European Arrival (Pre-1840)

Archaeological evidence suggests that Aboriginal people have inhabited the Gold Coast region for about 23,000 years before European settlement and the present. By the early 18th century there were several distinct clan estate groups (previously referred to as tribes) living between the Tweed and Logan Rivers; they are believed to be: the Gugingin, Bullongin, Kombumerri, Tul-gi-gin, Moorang-Mooburra, Cudgenburra, Birinburra, Wangerriburra, Mununjali[16] and Migunberri.[17]

The coastal clans of the area were hunters, gatherers and fishers. The Stradbroke Island blacks had dolphins aid them in the hunting and fishing processes. On sighting a shoal of mullet, they would hit the water with their spears to alert their dolphins, to whom they gave individual names, and the dolphins would then chase the shoal towards the shore, trapping them in the shallows and allowing the men to net and spear the fish. Some modern traditions state that this practice was shared by the Yugameh Kombumerri clan.[18]

The dolphin is known to have played an important role in a myth of the Nerang River Yugambeh, according to which the culture hero Gowonda was transformed into one on his death.[19] Various species were targeted in various seasons, including shellfish including eugaries, (cockles or pipis), oysters and mudcrabs. In winter, large schools of finfish species "running" along the coast in close inshore waters were targeted, those being sea mullet, which were followed by a fish known as tailor. Turtles and dugong were eaten, but the latter only rarely due to their more northerly distribution.

Various species of parrots and lizards were eaten along with bush honey. Echidnas, (an Australian native similar to a porcupine, but a monotreme not a rodent), are still hunted with dogs today and various marsupials including koalas and possums were also consumed. Numerous plants and plant products were included in the diet including macadamias and Bunya nuts and were used for medicinal purposes.

The area around present day Bundall, proximate to the Nerang River and Surfers Paradise, along with various other locations in the region was an established meeting place for tribes visiting from as far away as Grafton and Maryborough. Great corroborees were held there and traces of Aboriginal camps and intact bora rings are still visible in the Gold Coast and Tweed River region today.

Settlement Period (1840-1900)

The earliest mention of the Yugambeh comes from the diary of the Reverend Henry Stobart in 1853, who remarked on the abundance of resources in the area, and noted in particular thriving stands of walking stick palms, endemic to the Numinbah Valley and in Yugambeh called midyim,[20] a resource already being harvested for sale in England.[21] William E. Hanlon's family of English immigrants settled there around 1863. He states that the Yugambeh were friendly from the outstart:-

There were many blacks in the district, but on no occasion did they give us any trouble. On the contrary, we were always glad to see them, for they brought us fish, kangaroo tails, crabs, or honey, to barter for our flour, sugar, tea, or "tumbacca."[22]

As settlers encroached Yugambeh lands were alienated from their traditional users and by the turn of the century they were being forced into reserves such as that created at Deebing Creek.[23] Many Yugambeh remained in their traditional country and found employment with farmers, oyster producers and fishermen, timber cutters and mills constructed for the production of resources like sugar and arrowroot, whilst continuing to varying degrees with Yugambeh cultural practices, laws and customs. Many of them, both men and women (and sometimes children), found employment as servants or staff in the houses of the wealthy squatters and businessmen. Hanlon wrote of the areas rich resources. In a single morning he and 4 friends shot down 200 bronzewing pigeons[24] and large stands of much sought after red cedar, pine and beech were harvested by incoming woodcutters, while stands of the now highly prized tulip wood were burnt off as "useless".[25] Returning to the area in the early 1930s after a half century absence, he wrote:-

I found the rivers denuded of all their old and glorious scrubs, and their whilom denizens were neither to be seen nor heard. The streams themselves seemed to be sullen and sluggish, and polluted, and wore an air of being ashamed of their now-a-days nudity. Utility and ugliness were the dominant notes everywhere. In many places the physical features of the places were changed or entirely obliterated; watercourse and chain of ponds of my day were, nearly all, filled in with the accumulated debris of the past half century or so.[22]

The Yugambeh suffered from violent attacks undertaken by the Australian native police under their colonial leaders. According to the informant John Allen, over 60 years old at the time, and referring to his earliest memories sometime in the 1850s, a group of his tribe were surprised by troopers at Mount Wetheren and fired upon.

The blacks—men, women, and children—were in a dell at the base of a cliff. Suddenly a body of troopers appeared on the top of the cliff and without warning opened fire on the defenceless party below. Bullumm remembers the horror of the time, of being seized by a gin and carried to cover, of cowering under the cliff and hearing the shots ringing overhead, of the rush through the scrub to get away from the sound of the death-dealing guns. In this affair only two were killed, an old man and a gin. Those sheltered under the cliff could hear the talk of the black troopers, who really did not want to kill, but who tried to impress upon the white officer in charge the big number they had slaughtered.[26]

In 1855 an incident caused by a local tribesman sparked off a running spree of killings as troopers sought to kill the culprit. Allen recounted the story thus:

'About 1855. A German woman and her boy were killed at Sandy Creek, Jimboomba, near where is now the McLean Bridge, by a blackfellow known as "Nelson." The murderer was coming back from Brisbane on horseback and met the woman and boy on the road walking to Brisbane. The man was caught soon after committing the crime, but escaped from custody. He was a Coomera black, but sometimes lived with the Albert and Nerang tribes. The black troopers knew this, and were constantly on his tracks but never caught him. They had no scruples in shooting any blacks in the hope that the victim might be the escaped murderer. From 30 to 40 blacks were killed by troopers in this way, but "Nelson" died a natural death in spite of it all, some years after in Beenleigh.'[26]

In 1857, he recalled, again under the direction of Frederick Wheeler, a further massacre took place on the banks of the Nerang River (which may have followed theft on William Duckett White's Murry Jerry run there):[27]

A party of " Alberts," among whom was old blind Nyajum, was there camped on a visit to their friends and neighbours of the Nerang and Tweed. There had been a charge of cattle-killing brought against the local tribes, and someone had to pay. The police heard of this camp, and, under command of Officer Wheeler, cut it off on the land side with a body of troopers. The alarm was given. The male aboriginals plunged into the creek, swam to the other side, and hid in the scrub. The black troopers again were bad marksmen—probably with intent—as the only casualties were one man shot in the leg and one boy drowned. The old blind man had been hidden under a pile of skins in a hut, but was found by the troopers and dragged out by the heels. The gins told the troopers he was blind from birth. The troopers begged the officer not to order the poor fellow to be killed. The gins crowded round Wheeler imploring mercy for the wretched victim; some hung on to the troopers to prevent them firing. But prayers were useless; Wheeler was adamant. The gins were dragged off or knocked off with carbines, and the blind man was then shot by order of the white officer.'[26]

In another incident, which took place in 1860, six Yugambeh youths were kidnapped from camps in the area of the Nerang River area and forcibly transported to Rockhampton where they were to be inducted into, and trained to carry out punitive missions, by Frederick Wheeler, an officer with a notorious record for brutality. On witnessing the murder of one of the trainees, the small group planned their escape and, one night, snuck away to embark on an epic walk of some 550 kilometres back home. Fearing betrayal, they shied clear even of other aboriginal groups of their route which followed the coast on their left. After three months trekking, one youth climbed a tree and cried out Wollumbin! Wollumbin! (Mount Warning), much in the manner of the Greeks in Xenophon's Anabasis. They had made it back home. One of the youths, Keendahn, who was ten years old at the time, was so traumatised by the experience that he would hide in the bush for decades later, whenever word of police in the vicinity reached their camps.[28]

Modern day

Due to the harshness of the 1897 Act, and the various equally draconian amendments to it in the last century, and with respect to various government administrations, Yugambeh people have to date maintained a relatively low political profile in the region so that they would not be removed from their families, or from their traditional country with which they had (and retain) strong spiritual links.

As a result, and since that time, the Yugambeh people have maintained close and generally closed networks of communication amongst themselves regarding their cultural practices and use of language which were not accommodated by the authorities.

Commonwealth Games 2018

The Yugambeh People were involved with the Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games Corporation (GOLDOC) community consultation with Traditional Owners since early 2015 which lead to the establishment of a Yugambeh Elders Advisory Group (YEAG) consisting of nine local aunts and uncles[29] . A Reconciliation Action Plan (RAP) was developed for the Commonwealth Games 2018, and endorsed by YEAG, this was the first International Sporting Event and Commonwealth Games to have a RAP.[30]

The Games Mascot was named Borobi, a word from the local Yugambeh language, meaning Koala; it was the first Australian sporting mascot to have an Indigenous name, which one Yugambeh descendant described as:

....a huge credit to our Elders and their work to revive language in everyday use, and it sends a powerful message to the rest of the world that the Commonwealth Games 2018 is serious about including Aboriginal story and culture.[31]

Yugambeh culture was incorporated into the Queens Baton with the use of native Macadamia wood, known in Yugambeh language as Gumburra. A story given by Elder Patricia O'Connor served as the inspiration for the Baton, as Macadamia nuts were often planted by groups travelling through country, to mark the way and provide sustenance to future generations - upon hearing the story, the baton's designers decided to use macadamia wood as a symbol of traditional sustainable practice.

When I was a little girl, probably seven or eight years old, I was cracking Queensland nuts,

My grandmother said "when I was a little girl I planted those nuts as I walked with my father along the Nerang river" and she said "you call them Queensland nuts, I call them Goomburra".

She planted them when she walked with her dad, and as an adult she saw them bearing fruit.

Patricia O'Connor and another Elder, Ted Williams, travelled to London to launch the Queen's Baton Relay- marking the first time Traditional Owners had attended the ceremony.[32] After a 288-day journey, the Queen's Baton was passed from New Zealand to Australia in the Māori Court of the Auckland Museum, where in a traditional farewell ceremony to farewell and handover the baton the Ngāti Whātua elders of Auckland passed the Queen's Baton to representatives of the Yugambeh people. Yugambeh performers were present to respond to the Maori farewell ceremony.[33][34]

Social organisation

Social divisions

R. H. Mathews visited the Yugambeh in 1906 and picked up the following information concerning their social divisions, which were fourfold. Mathews also noted specific animals, plants and stars as associated with the divisions.[35]

| Mother | Father | Son | Daughter |

|---|---|---|---|

| Baranggan | Deroin | Banda | Bandagan |

| Bandjuran | Banda | Deroin | Deroingan |

| Deroingan | Barang | Bandjur | Bandjuran |

| Bandagan | Bandjur | Barang | Baranggan |

Clans

The Yugambeh People are made of 9 named clan estate groups, each with their own allocated area of country; family groups did not often travel into the country of other Yugambeh family groups without reason. Clans would frequently visit and stay on each other's estates during times of ceremony, dispute resolution, resource exchange, debt settlement and scarcity of resources, but followed strict protocols governing announcing their presence and their use of other's lands.

Each clan has ceremonial responsibilities in their respective countries, like those that ensure that food and medicinal plants grow and that there is a plentiful supply of fish, shellfish, crabs, and other animal food in general.[36] The clan group boundaries tend to follow noticeable geological formations such as river basin systems and mountain ranges.

Eastern Clans / Saltwater

Bullongin

Etymology: River People

Location: The Coomera River basin.

"Alternative names": Balunjali

Etymology: Mudgrove-worm People.[lower-alpha 3]

Location: The Nerang River basin.[38]

"Alternative names": Chabbooburri, Birinburra

Western Clans / Freshwater

Gugingin

Etymology: Northern People

Location: The Lower-Logan River Basin.[39]

"Alternative names": Guwangin

Mununjali

Etymology: Burnt-Earth People

Location: Beaudesert.[39]

Migunberri

Etymology: Mountain Spike People

Location: Christmas Creek.[39]

"Alternative names": Migani, Balgaburri

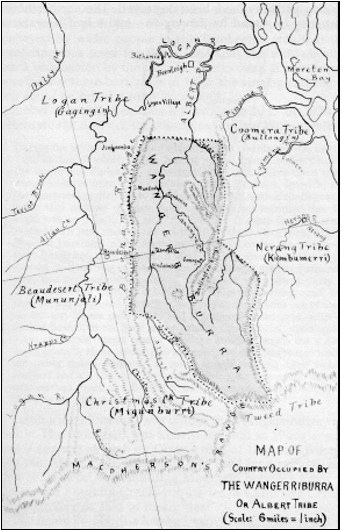

Wanggeriburra

Etymology: Pretty-Faced Wallaby People

Location: Albert River basin.[39]

Valley clans

Tul-gi-gin

Etymology: Dry-Forest People

Location: The Northern Lower-Tweed River basin.

"Alternative names": Tulgiburri

Moorung-Mooburra

Etymology: Water-Vine People

Location: Upper-Tweed River basin.

Cudgenburra

Etymology: Red-Ochre People

Yugambeh Museum

The Yugambeh Museum, Language and Heritage Research Centre is located on the corner of Martens Street and Plantation Road in Beenleigh. It was opened in 1995 by Senator Neville Bonner, Australia's first Aboriginal Federal Parliamentarian.

The museum is the main resource for objects and information relating to the ongoing story of the Yugambeh people, their spiritual and cultural history, and their language. The museum organises education programs, exhibitions and events, including traditional ceremonies.[42]

Armed Forces Service

The Yugambeh, like other Aboriginal Australians, had their efforts to join the armed forces resisted due to official policy that saw them as unsuitable because of their "racial origin". In a few cases however they were successful, with 10 Yugambeh people serving in World War I, then subsequently 47 in World War II, they have fought in every major conflict from World War I to the 1991 Gulf War.

The Yugambeh Museum maintains records and research on Yugambeh descendants who served in the armed forces.

After service, their contributions were rarely recognised by historians or brought to the attention of the public.[43]

War memorial

The Yugambeh, represented by the Kombumerri Aboriginal Corporation for Culture with the support and assistance from the Gold Coast City Council, erected a War Memorial on the site of the Jebribillum Bora Park Burleigh Heads at Burleigh Heads in 1991.[44][45]

Jebbribillum bora has been chosen as a site most appropriate for the Yugambeh Aboriginal War Memorial because of its spiritual and historical significance. Jebbribillum symbolises the fighting waddy of Jabreen, the maker of boomerangs - the creation spirit who made us human. [46]

The memorial consists of a stone taken from nearby Mt Tamborine, a sacred site to the Yugambeh clans. Sources provide three transcriptions for the inscription, which means "Many Eagles(Yugambeh warriors) Protecting Our Country":

Native title

The Yugambeh clans filed a Native Title Claim in the Federal Court on 27 June 2017 under the application name 'Danggan Balun (Five Rivers) People'. Their claim was accepted for registration by the Registrar on 14 September 2017.

The claim names nineteen Apical Ancestors and encompasses lands and waters across five Local Government Areas within the State of Queensland.[48]

Previous claims

The Eastern Clans filed a Native Title Claim in the Federal Court on the 5 September 2006 under the application name 'Gold Coast Native Title Group (Eastern Yugambeh)'. Their claim was accepted for registration by the Registrar on 23 September 2013.

The claim named ten Apical Ancestors and encompassed lands and waters across the Gold Coast Local Government Area within the State of Queensland. It was Dismissed on the 13 September 2014 with a Part Determination that Native Title did not exist on lands granted a prior lease.[49][50]

Notable people

- Billy Drumley - Indigenous community leader

- Ellen van Neerven - Writer.[51]

Alternative names

Some words

- dagay. (whiteman/ghost)

Notes

- ↑ the word, referring to the indigenous people, means "Eaglehawk".[2]

- ↑ "Regarding Ngaragwal, Woodenbong opinion is agreed in placing it on the coast between Southport and Cape Byron, which would equate it with A&L's Nerang people. Those at Woodenbong can give no information on Ngaragwal and claim it is quite different from Gidabal. Allen appeared to consider this coastal language as a dialect of Bandjalang, yet not mutually intelligible with Yugumbir.".[8]

- ↑ According to Germaine Greer, Archibald Meston called people in this area Talgiburri, equivalent to what Margaret Sharpe transcribes as the Dalgaybara, a word meaning "people of the dalgay or dry sclerophyll forest" rather than saltwater people. Greer argues that there is an apparent confusion, asserting that "The Kombumerri called themselves people of the dry forest; Bullum called them mangrove-worm (cobra) eaters, and now they describe themselves as 'saltwater people'."[37]

Citations

- ↑ Tindale 1974, p. 42.

- ↑ Prior et al. 1887, p. 213.

- ↑ Sharpe 2005b, p. 2.

- ↑ Sharpe 2007, pp. 53–55.

- ↑ ABS 2017.

- ↑ Crowley 1978, p. 145.

- ↑ Longhurst 1980, p. 18.

- ↑ Cunningham 1969, p. 122 note 34.

- ↑ Livingstone 1892, p. 2.

- 1 2 Crowley 1978, p. ?.

- ↑ Tindale 1974, p. 197.

- 1 2 Tindale 1974, p. 171.

- ↑ Horsman 1995, p. 53.

- ↑ Best & Barlow 1997, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Hanlon 1935, pp. 233–4.

- ↑ Holmer 1983, p. ?.

- ↑ Allen & Lane 1914, p. ?.

- ↑ Best & Barlow 1997, pp. 16–21.

- ↑ Longhurst 1980, p. 19.

- ↑ Greer 2014, p. 123.

- ↑ Best 1994, p. 88.

- 1 2 Hanlon 1935, p. 210.

- ↑ Best 1994, p. 90.

- ↑ Hanlon 1935, p. 212.

- ↑ Hanlon 1935, p. 214.

- 1 2 3 Allen & Lane 1914, p. 24.

- ↑ Longhurst 1980, p. 20.

- ↑ Keendahn.

- ↑ GC2018 - RAP.

- ↑ GC2018 YouTube 2018.

- ↑ Borobi Mascot.

- ↑ NITV 2018.

- ↑ QBR 2017.

- ↑ NZOC 2017.

- ↑ Mathews 1906, pp. 74–86.

- ↑ Best & Barlow 1997, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Greer 2014, pp. 118–119.

- ↑ Allen & Lane 1914, p. 36.

- 1 2 3 4 Horsman 1995, p. 42.

- ↑ Bray 1899, p. 93?.

- ↑ Tweed Regional Museum.

- ↑ YM 2017.

- ↑ O'Connor 1991.

- 1 2 Memorial 2017.

- 1 2 QWMR 2009.

- ↑ Best & Barlow 1997, pp. 50.

- ↑ Monument.

- ↑ NNTT 2017.

- ↑ NNTT.

- ↑ Stolz 2006.

- ↑ Wheeler & van Neerven 2016, p. 294.

- ↑ Meston & Small 1898, p. 46.

- ↑ Fison & Howitt 1880, pp. 205,268,327.

- ↑ Howitt 1904, pp. 137,318–319,326,354,385,468,578–583,767.

Sources

- "Aboriginal Cultural Heritage". Tweed Regional Museum. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Allen, John; Lane, John (1914). "Grammar, Vocabulary, and Notes of the Wangerriburra Tribe" (PDF). Annual Report of the Chief Protector of Aborigines for the year 1913. Brisbane: Anthony James Cumming for the Queensland Government. pp. 23–36.

- Australian Standard Classification of Languages (ASCL), 2016: What has changed. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 28 March 2017.

- Best, Ysola (1994). "An Uneasy Coexistence: An Aboriginal Perspective of Contact History in southeast Queensland" (pdf). Aboriginal History. 18 (1/2): 87–94.

- Best, Ysola; Barlow, Alex (1997). Kombumerri, Saltwater People. Port Melbourne: Heinemann Library Australia. ISBN 978-1-863-91037-8. OCLC 52249982.

- "Borobi the Commonwealth Games Mascot! | Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Languages". State Library of Queensland. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Bray, Joshua (21 November 1899). "Tweed River. On dialects and place names". Science of Man. 2 (10): 192–194.

- "Burleigh Bora ring to host memorial service for Gold Coast's Yugambeh and Aboriginal servicemen". Gold Coast Sun. 2 November 2017.

- "Burleigh Heads Aboriginal War Memorial". Queensland War Memorial Register. 16 March 2009.

- Crowley, Terry (1978). The middle Clarence dialects of Bandjalang. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies.

- Cunningham, M. (1969). A Description of the Yugumbir Dialect of Bandjalang (PDF). Volume 1. University of Queensland Papers. pp. 69–122.

- Dixon, Robert M. W. (2002). Australian Languages: Their Nature and Development. Volume 1. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-47378-1.

- Dutton, H. S. (22 March 1904a). "Aboriginal place names". Science of Man. 7 (2): 24–27.

- Dutton, H. S. (27 June 1904b). "Aboriginal dialects and place names (Queensland)". Science of Man. 7 (5): 72–77.

- "Elders take centre stage at Buckingham Palace". NITV. 14 March 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- "Extract from Schedule of Native Title Applications" (PDF). National Native Title Tribunal.

- "Extract from Schedule of Native Title Applications" (PDF). National Native Title Tribunal. 14 September 2017. Retrieved 18 September 2017.

- Fison, Lorimer; Howitt, Alfred William (1880). Kamilaroi and Kurnai (PDF). Melbourne: G Robinson.

- "GC2018 Reconciliation Action Plan". Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games. 29 May 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2018 – via YouTube.

- Greer, Germaine (2014). White Beech: The Rainforest Years. A&C Black. ISBN 978-1-408-84671-1.

- Hanlon, William E. (1935). "The early settlement of the Logan and Albert districts" (pdf). Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland. 2 (5): 208–262.

- Holmer, Nils M. (1983). Linguistic Survey of South-Eastern Queensland. Pacific Linguistics. ISBN 978-0-858-83295-4.

- Horsman, Margaret Joan (1995). Patterns of Settlement, Development and Land Usage: Currumbin Valley 1852-1915 (PDF). University of Queensland MA Thesis.

- Howitt, Alfred William (1904). The native tribes of south-east Australia (PDF). Macmillan.

- "The International QBR Journey Ends In New Zealand: Queen's Baton Relay". Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games. 23 December 2017. Retrieved 14 March 2018 – via YouTube.

- Kidnapped: Keendahn's story. National Museum Australia.

- Livingstone, H. (1892). "Short Grammar and Vocabulary of the Dialect spoken by the Minyung People" (PDF). In Fraser, John. An Australian language as spoken by the Awabakal, the people of Awaba, or lake Macquarie (near Newcastle, New South Wales) being an account of their language, traditions, and customs. Sydney: C. Potter, Govt. Printer. pp. Appendix 2–27.

- Longhurst, Robert I. (1980). "The Gold Coast: Its First Inhabitants" (PDF). John Oxley Journal: a bulletin for historical research in Queensland. John Oxley Library. 1 (2): 15–24.

- Mathews, R. H. (1906). "Notes on the Aborigines of the Northern Territory, Western Australia and Queensland". Queensland Geographical Journal. 22: 74–86.

- Meston, Archibald; Small, John Frederick (21 March 1898). "Customs and traditions of the Clarence River aboriginals". Science of Man. 1 (2): 46–47.

- O'Connor, Rory (1991). Yugambeh in defence of our country - mibun wallul mundindehla ŋaliŋah dhagun. Kombumerri Aboriginal Corporation for Culture.

- O'Donnell, Dan (1990). "The Ugarapul tribe of the Fassifern Valley" (PDF). Journal of the Royal Historical Society of Queensland. 14 (4): 149–160.

- Prior, T.de M. M.; Landsborough, W.; White, W.G.; O'Connor, J. (1887). "Between Albert and Tweed Rivers" (PDF). In Curr, Edward Micklethwaite. The Australian race: its origin, languages, customs, place of landing in Australia and the routes by which it spread itself over the continent. Volume 3. Melbourne: J. Ferres. pp. 231–239.

- "Queen's Baton Farewelled in Auckland". New Zealand Olympic Committee. 23 December 2017.

- "RAP GOVERNANCE & ENGAGEMENT | Gold Coast 2018 Commonwealth Games". Gold Coast 2018. Retrieved 14 March 2018.

- Sharpe, Margaret C. (2005a). Grammar and texts of the Yugambeh-Bundjalung dialect chain in Eastern Australia. Munich: Lincom Europa. ISBN 978-3-895-86784-2.

- Sharpe, Margaret C. (2005b). An Introduction to the Yugambeh-Bundjalung Language and its Dialects (4th ed.). Armidale, NSW: University of New England.

- Sharpe, Margaret C. (2007). "A revised view of the verbal suffixes of Yugambeh-Bundjalung". In Siegel, Jeff; Lynch, John Dominic; Eades, Diana. Language Description, History and Development: Linguistic Indulgence in Memory of Terry Crowley. John Benjamins Publishing. pp. 53–68. ISBN 978-9-027-25252-4.

- Steele, John Gladstone (1984). Aboriginal Pathways: in Southeast Queensland and the Richmond River. University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-702-25742-1.

- Stolz, Greg (21 September 2006). "Tribes feud over claim". Courier-Mail. Brisbane.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Jukambe (NSW)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- Wheeler, Belinda; van Neerven, Ellen (December 2016). "An Interview with Heat and Light Author Ellen van Neerven". Antipodes. 30 (2): 294–300. JSTOR 10.13110/antipodes.30.2.0294.

- "Yugambeh Aboriginal War Memorial". Gold Coast Sun.

- "Yugambeh Museum Language and Heritage Research Centre". earthstory.com.au. 2017.