Yellow-eyed penguin

| Yellow-eyed penguin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Sphenisciformes |

| Family: | Spheniscidae |

| Genus: | Megadyptes |

| Species: | M. antipodes |

| Binomial name | |

| Megadyptes antipodes | |

| |

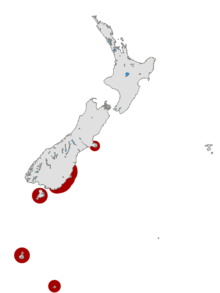

| Distribution of Yellow-eyed penguin | |

The yellow-eyed penguin (Megadyptes antipodes) or hoiho is a penguin native to New Zealand. Previously thought closely related to the little penguin (Eudyptula minor), molecular research has shown it more closely related to penguins of the genus Eudyptes. Like most other penguins, it is mainly piscivorous.

The species breeds along the eastern and south-eastern coastlines of the South Island of New Zealand, as well as Stewart Island, Auckland Islands, and Campbell Islands. Colonies on the Otago Peninsula are a popular tourist venue, where visitors may closely observe penguins from hides, trenches, or tunnels.

On the New Zealand mainland, the species has experienced a significant decline over the past 20 years. On the Otago Peninsula, numbers have dropped by 75% since the mid-1990s and population trends indicate the possibility of local extinction in the next 20 to 40 years. While the effect of rising ocean temperatures is still being studied, an infectious outbreak in the mid 2000s played a large role in the drop. Human activities at sea (fisheries, pollution) may have an equal if not greater influence on the species' downward trend.[2]

Taxonomy

The yellow-eyed penguin is the sole extant species in the genus Megadyptes. (A smaller, recently extinct species, M. waitaha, was discovered in 2008.[3]) Previously thought closely related to the little penguin (Eudyptula minor), new molecular research has shown it more closely related to penguins of the genus Eudyptes. Mitochondrial and nuclear DNA evidence suggests it split from the ancestors of Eudyptes around 15 million years ago.[4]

The yellow-eyed penguin was described by Jacques Bernard Hombron and Honoré Jacquinot in 1841. The Māori name is hoiho.

Description

This is a mid-sized penguin, measuring 62–79 cm (24–31 in) long (fourth largest penguin). Weights vary through the year being greatest, 5.5 to 8 kg (12–18 lbs), just before moulting and least, 3 to 6 kg (6.6–13.2 lbs), after moulting. The males are larger than the females.[5][6] It has a pale yellow head and paler yellow iris with black feather shafts. The chin and throat are brownish-black. There is a band of bright yellow running from its eyes around the back of the head. The juvenile has a greyer head with no band and their eyes have a grey iris.

The yellow-eyed penguin may be long lived, with some individuals reaching 20 years of age. Males are generally longer lived than females, leading to a sex ratio of 2:1 around the age of 10–12 years.[7]

Distribution and habitat

This penguin usually nests in forest or scrub, among native flax (Phormium tenax) and lupin (Lupinus arboreus), on slopes or gullies, or the shore itself, facing the sea. These areas are generally sited in small bays or on headland areas of larger bays.[8] It is found in New Zealand, on the south-east coast of the South Island most notably on Otago Peninsula, Foveaux Strait, Stewart Island, and sub-Antarctic islands of Auckland and Campbell Islands. It expanded its range from the sub-Antarctic islands to the main islands of New Zealand after the extinction of the Waitaha penguin several hundred years ago.

Health

In spring 2004, a previously undescribed disease killed off 60% of yellow-eyed penguin chicks on the Otago peninsula and in North Otago. The disease has been linked to an infection of Corynebacterium, a genus of bacteria that also causes diphtheria in humans. It has recently been described as diphtheritic stomatitis. However, it seems as if this is just a secondary infection. The primary pathogen remains unknown. A similar problem has affected the Stewart Island population.[9]

Foraging behaviour

The yellow-eyed penguin forages predominantly over the continental shelf between 2 km (1 mi) and 25 km (16 mi) offshore, diving to depths of 40 m (131 ft) to 120 m (394 ft) [10][11] Breeding penguins usually undertake two kinds of foraging trips: day trips where the birds leave at dawn and return in the evening ranging up to 25 km from their colonies, and shorter evening trips during which the birds are seldom away from their nest longer than four hours or range farther than 7 km.[11] Yellow-eyed penguins are known to be an almost exclusive benthic forager that searches for prey along the seafloor. Accordingly, up to 90% of their dives are benthic dives.[11] This also means that their average dive depths are determined by the water depths within their home ranges.[12]

Diet

Around 90% of the yellow-eyed penguin's diet is made up of fish, chiefly demersal species that live near the seafloor (e.g. blue cod (Parapercis colias), red cod (Pseudophycis bachus), opalfish (Hemerocoetes monopterygius) [13]). Other species taken are New Zealand blueback sprat (Sprattus antipodum) and cephalopods such as arrow squid (Nototodarus sloanii). Jellyfish including species in the genera Chrysaora and Cyanea were found to be actively sought-out food items, while they previously had been thought to be only accidentally ingested. Similar preferences were found in the Adélie penguin, little penguin and Magellanic penguin.[14]

Breeding

Whether yellow-eyed penguins are colonial nesters has been an ongoing issue with zoologists in New Zealand. Most Antarctic penguin species nest in large high density aggregations of birds. For an example see the photo of nesting emperor penguin. In contrast yellow-eyed penguins do not nest within visual sight of each other. While they can be seen coming ashore in groups of four to six or more individuals then disperse along track to individual nests sites out of sight of each other. The consensus view of New Zealand penguin workers is that it is preferable to use habitat rather than colony to refer to areas where yellow-eyed penguins nest. Nest sites are selected in August and normally two eggs are laid in September. The incubation duties (lasting 39–51 days) are shared by both parents who may spend several days on the nest at a time. For the first six weeks after hatching, the chicks are guarded during the day by one parent while the other is at sea feeding. The foraging adult returns at least daily to feed the chicks and relieve the partner.

After the chicks are six weeks of age, both parents go to sea to supply food to their rapidly growing offspring. Chicks usually fledge in mid-February and are totally independent from then on. Chick fledge weights are generally between 5 and 6 kg.

First breeding occurs at three to four years of age and long term partnerships are formed.

Penguins and humans

Conservation

This species of penguin is endangered, with an estimated population of 4000. It is considered one of the world's rarest penguin species. The main threats include habitat degradation and introduced predators. It may be the most ancient of all living penguins.[15]

A reserve protecting more than 10% of the mainland population was established at Long Point in the Catlins in November 2007 by the Department of Conservation and the Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust.[16][17]

In August 2010, the yellow-eyed penguin was granted protection under the U.S. Endangered Species Act.[18]

Tourism

Several mainland habitats have hides and are relatively easily accessible for those wishing to watch the birds come ashore. These include beaches at Oamaru, Moeraki light-house, a number of beaches near Dunedin, and The Catlins. In addition, commercial tourist operations on Otago Peninsula also provide hides to view yellow-eyed penguins.

In culture

- The hoiho appears on the reverse side of the New Zealand five-dollar note.

- The yellow-eyed penguin is the mascot to Dunedin City Council's recycling and solid waste management campaign.[19]

- The yellow-eyed penguin is also featured in Farce of the Penguins, in which they complain about global warming.

References

- ↑ BirdLife International (2012). "Megadyptes antipodes". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2013.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 26 November 2013.

- ↑ Mattern T, Meyer S, Ellenberg U, Houston DM, Darby JD, Young M, van Heezilk Y, Seddon PJ (2017). "Quantifying climate change impacts emphasises the importance of managing regional threats in the endangered Yellow-eyed penguin". PeerJ. 5: e3272. doi:10.7717/peerj.3272. PMC 5436559. PMID 28533952.

- ↑ Boessenkool, Sanne; et al. (2008). "Relict or colonizer? Extinction and range expansion of penguins in southern New Zealand". Proc. R. Soc. B. 276 (1658): 815–821. doi:10.1098/rspb.2008.1246. PMC 2664357. PMID 19019791.

- ↑ Baker AJ, Pereira SL, Haddrath OP, Edge KA (2006). "Multiple gene evidence for expansion of extant penguins out of Antarctica due to global cooling". Proc Biol Sci. 273 (1582): 11–17. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3260. PMC 1560011. PMID 16519228.

- ↑ Marion, Remi, Penguins: A Worldwide Guide. Sterling Publishing Co. (1999), ISBN 0-8069-4232-0

- ↑

- ↑ Richdale, L (1957). A population study of penguins. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- ↑ Williams, Tony D. (1995). The Penguins. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-854667-X.

- ↑ Kerrie Waterworth, Mystery illness strikes penguins, Sunday Star Times, 25 November 2007.

- ↑ Moore, P. J. 1999: Foraging range of the yellow-eyed penguin, Megadyptes antipodes. Marine Ornithology 27: 49-59

- 1 2 3 Mattern, T.; Ellenberg, U.; Houston, D.M.; Davis, L.S. 2007: Consistent foraging routes and benthic foraging behaviour in yellow-eyed penguins. Marine Ecology Progress Series 343: 295-306

- ↑ Mattern, T.; Ellenberg, U.; Houston, D.M.; Lamare, M.; van Heezik, Y.; Seddon, P.J., Davis, L.S. 2013: The Pros and Cons of being a benthic forager: How anthropogenic alterations of the seafloor affect Yellow-eyed penguis. Keynote presentation. 8th International Penguin Conference, Bristol, UK. 2–6 September 2013. https://web.archive.org/web/20131111100029/combine.cs.bris.ac.uk/opencms/ipc/materials/IPC8_Abstract_Book_complete.pdf

- ↑ Moore, P.J.; Wakelin, M.D. 1997: Diet of the yellow-eyed penguin Megadyptes antipodes, South Island, New Zealand, 1991-1993. Marine Ornithology 25:17-29

- ↑ Christie Wilcox (15 September 2017). "Penguins Caught Feasting on an Unexpected Prey". National Geographic.

- ↑ Other Penguin Species. Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust. Accessed 28 November 2007.

- ↑ Gwyneth Hyndman, Land set aside for yellow-eyed penguin protection in Catlins. The Southland Times, Wednesday, 28 November 2007.

- ↑ 12km coastal reserve declared for yellow-eyed penguins, Radio New Zealand News, 27 November 2007.

- ↑ Five Penguins Win U.S. Endangered Species Act Protection Turtle Island Restoration Network

- ↑ "Rubbish and Recycling - Services". Dunedin City Council. Retrieved 14 March 2011.

External links

| Wikispecies has information related to Megadyptes antipodes |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Megadyptes antipodes. |

- BBC Science and nature page about Megadyptes waitaha

- Official Yellow-eyed Penguin Trust site in New Zealand

- Yellow-eyed penguin facts at Penguins in New Zealand

- penguinpage.net - Research blog about a project investigating yellow-eyed penguin foraging behaviour

- Yellow-eyed penguins from the International Penguin Conservation website

- "Hoiho (Megadyptes antipodes) recovery plan 2000–2025" (PDF). Department of Conservation, Wellington, New Zealand. 2001. Retrieved 2007-10-04.

- Roscoe, R. "Yellow-eyed Penguin". Photo Volcaniaca. Retrieved 13 April 2008.