Western Australia Police

| Western Australia Police Force | |

|---|---|

Badge of the Western Australia Police | |

| Agency overview | |

| Formed | 1 January 1834 |

| Employees | 8,973 (30 June 2017)[1] |

| Annual budget | A$1.395 billion (2016–17)[2] |

| Jurisdictional structure | |

| Operations jurisdiction | Western Australia, Australia |

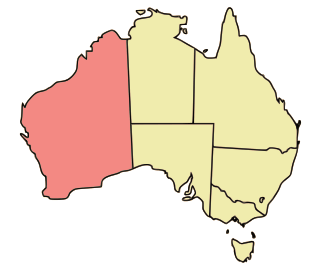

| |

| Map of Western Australia Police Force's jurisdiction. | |

| Size | 2,645,615 km2 |

| Population | 2,474,410[3] |

| Governing body | Government of Western Australia |

| Headquarters |

2 Adelaide Terrace, East Perth, WA 6004 31°57′41″S 115°52′43″E / 31.9613°S 115.8787°ECoordinates: 31°57′41″S 115°52′43″E / 31.9613°S 115.8787°E |

|

| |

| Minister responsible |

|

| Agency executive |

|

| Units |

List

|

| Facilities | |

| Stations | 158[5] |

| Website | |

| www.police.wa.gov.au | |

The Western Australia Police Force, colloquially WAPOL, provides police services throughout the state of Western Australia, an area of 2.5 million square kilometres, the world's largest non-federated area of jurisdiction, with a population of only 2.4 million, of which 1.94 million[6] reside in the Perth Metropolitan Region.

History

Early history

The genesis of the police was the appointment of a sheriff by Captain Stirling on 18 June 1829, as part of the proclamation of the Swan River Colony.[7] The proclamation provided for the appointment of a sheriff having under his direction a high constable, constables, bailiffs and surveyors of highways. The sheriff still exists as an officer of the Western Australian Justice Department—no longer having jurisdiction over police or highways. The sheriff retains responsibility for enforcement of court judgments and the administration of jury service. Police continue to carry out sheriff and bailiff duties, particularly in remote country locations.

Early colonial policemen were recruited by magistrates and worked part-time. They were paid only for specific tasks, such as one shilling for serving a summons. By 1830, there were fifteen part-time constables in the state, of whom five worked in Perth.

A mounted force was established in 1834, proving unpopular with citizens on the grounds that it was not efficient and was being paid out of their taxes for duties which the military should be performing. It was involved in the "Pinjarra Massacre", in which Captain Ellis, the police superintendent, was killed together with a large number of Aboriginal people.[8] The first full-time constable for Perth was appointed in 1840.

The Legislative Council passed a police ordinance in 1849 that outlined police powers and responsibilities. An organised police force was formally established in 1853.

Convict period

After convicts started arriving in the colony in 1849, the police acquired the duties of registering and supervising ticket-of-leave men.[9] By 1870, after transportation had ceased, some 1,244 ticket-of-leave men had to be supervised by 146 police employees.

Applicants for police service were required to be aged under forty, literate and physically fit. Leave was difficult to obtain and officers were not to appear in public when out of uniform. Until the end of the nineteenth century, the monthly pay day was marked by a parade with band.

A Criminal Investigation Department was set up in 1873, although two detectives had been sent out from Britain in 1854. A fingerprint bureau was set up in 1902 and the first female officer was appointed in 1917.

Organisation

The Police Headquarters is located in East Perth overlooking the Causeway, near the WACA Ground. The 1960s curved building also housed the former East Perth Lockup.[10] and a magistrates courtroom. The structure is entered on the State Heritage Register. Recruits are trained at the Western Australian Police Academy at Joondalup. Previously the Academy was located at Maylands, in premises still used by various units including the mounted and K-9 (police dog) sections.

The command structure has the state divided into three regions and sub-divided into fourteen districts. As of 2017 there were 35 metropolitan and 123 regional police stations.[11]:pp.8–9 The highest-ranking officer is the Commissioner of Police. As of October 2017, the Commissioner is Chris Dawson, who commenced duties on 16 August 2017.[12] There is an Assistant Commissioner (Professional Standards), a Deputy Commissioner (Operations), a Deputy Commissioner (Specialist Services) and an Executive Director.[13]:p.6 Politically, the service comes within the portfolio of the Minister for Police.

A number of specialist units have been established, including the Tactical Response Group (TRG), Dog Squad (K9), Gang Crime Squad, Crime Investigation and Intelligence Services, Water Police, Traffic Enforcement Group, Specialist Police Motorcycle Unit, Regional Operations Group, Police Air Wing, Liquor Enforcement Unit and the Gold Stealing Detection Unit.[14]

Personnel

As of 2017, some 6,793 police officers were employed, including auxiliary officers and Aboriginal liaison officers; together with about 2180 police staff.[15]:9 (Police staff includes public servants and wages employees, but not school street-crossing guards.) Females constituted 21.6% of the police officers, including two of 13 senior officers.[15]:149

Police Auxiliary Officers

The Western Australia Police have Police Auxiliary Officers (Custody Support), members of staff who are employed to support WA Police officers through the admission, custody and release of detainees in the Perth Watch House and other station-based lock-ups, including the supervision and transferring of detainees to court and for medical treatment in hospitals. Other duties include managing and handling drugs and firearms, processing property and exhibits and a range of station support tasks.[16] They are distinguishable by their maroon epaulettes, white name patches and their uniforms display 'Auxiliary Officer' instead of 'Police'.

Police Auxiliary Officers (Protective Service Officers) are authorised to carry a firearm and a Taser[17] and are equipped with telescopic batons, handcuffs and Oleoresin Capsicum (OC) Spray. They have limited police powers and training lasts only 12 weeks.[18]

Regional Operations Group

Created in 2004 the Regional Operations Group provides WAPOL with a specialist public order capability. The unit is split into two sub units, North and South. ROG officers undergo intensive public order training and typically carry extra equipment to assist with this whenever they are on duty.

Perth Police Complex

In 2013 the organisation opened a new facility at Northbridge. Accommodating up to 500 police officers, the complex includes the Perth Police Station, the Central Metropolitan District Office, the Northbridge Magistrate's Court and a new state-of-the-art Perth Watch House.[19][20] Before long, the police union complained that insufficient staff had been assigned to the new lock-up in the context of state government budget constraints.[21]

Commissioner of police

Traditionally the Commissioner came from within the service though, in 1994 and 1999, police commissioners were head-hunted from outside WA Police ranks. In 1994, Victorian Bob Falconer APM was imported from the Victoria Police where he had been a deputy commissioner. Falconer was effective in implementing the Delta Program designed to achieve organisational and cultural change.[22] Falconer later argued that internal measures were inadequate and that a standing crime and corruption commission was necessary to combat police corruption.[23] In 1999 Barry Matthews, then a deputy commissioner of the New Zealand Police, was appointed and served until 2004.[24] Matthews was, however, succeeded in June 2004 by Karl O'Callaghan APM, PhD who had been employed in the WA service since age 17 and was one of the service's first officers to achieve a PhD.[25] O'Callaghan retired on 14 August 2017 and was succeeded by Chris Dawson.[12]

Ranks

| Constable | Constable First Class | Senior Constable | Sergeant | Senior Sergeant | Inspector | Superintendent | Commander | Assistant Commissioner | Deputy Commissioner | Commissioner |

|  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |  |

All officers that graduate from the police academy become probationary constables for 18 months before graduating up to a normal constable. Their insignia stays the same as a normal constable. Constables are general duties officers and are not allowed to branch out to different divisions of the Western Australia Police Force. Any officer must reach the rank of First Class Constable before more opportunities with other divisions within the police become available.

Reform initiative

In 2013, the organisation announced "a new reform program Frontline 2020, to reposition the agency to deal with current and future demands". Goals include "locally focussed policing", demand reduction and a "leaner" approach.[13]:p.5

Equipment and weaponry

All officers are armed when on duty. The standard firearm is the Glock 22 .40-calibre pistol. Officers also carry the X-26 Taser Electronic Control Device (ECD), often described in the media as a "less-than-lethal-force" option. Prior to the Glock transition officers were armed with a .38 Special Smith & Wesson Model 10 as well as some units using the .40 S&W Smith & Wesson Sigma.[26]

Because of the weight of equipment carried on officers' belts, Western Australian uniformed officers are being progressively issued with equipment vests fitted with pockets to safely contain equipment including ammunition magazines for the service pistol, pepper spray, baton, handcuffs, radio and mobile phone. The vests are navy blue in colour, although a fluorescent yellow version is worn for some operations.

Further specialised equipment is utilised by the TRG, as detailed in that section below.

Vehicles

Marked police cars

Marked Yamaha FJR1300 Traffic Enforcement Group Motorcycle

Marked Yamaha FJR1300 Traffic Enforcement Group Motorcycle_SV6_Sportwagon%2C_Western_Australia_Police_(2017-11-18).jpg) Holden VF II SV6 Commodore Sportwagon – General policing patrol

Holden VF II SV6 Commodore Sportwagon – General policing patrol_XR6_sedan%2C_Western_Australia_Police_(2018-07-19).jpg) Ford Falcon FG X XR6 sedan – General policing patrol

Ford Falcon FG X XR6 sedan – General policing patrol_SV6_sedan%2C_Western_Australia_Police_(2016-11-12).jpg) Holden VF II SV6 Commodore sedan – Traffic Enforcement Group 2

Holden VF II SV6 Commodore sedan – Traffic Enforcement Group 2_SR_4-door_utility%2C_Western_Australia_Police_(2017-11-18).jpg) Western Australia Police Toyota HiLux paddy wagon

Western Australia Police Toyota HiLux paddy wagon_SR_4-door_utility%2C_Western_Australia_Police_(2018-08-06).jpg) Western Australia Police Toyota HiLux paddy wagon

Western Australia Police Toyota HiLux paddy wagon_utility%2C_Western_Australia_Police_(2018-08-06).jpg) Holden VF Ute - Prisoner van (new livery)

Holden VF Ute - Prisoner van (new livery)

Unmarked police cars

_Sportivo_sedan_(2017-02-18)_01.jpg) Toyota Aurion Sportivo

Toyota Aurion Sportivo_SV6_sedan_(2017-11-18).jpg) Holden Commodore SV6

Holden Commodore SV6_XR6_sedan_(2017-11-18).jpg) Ford Falcon XR6

Ford Falcon XR6_TX_AWD_wagon_(2018-09-17).jpg) Ford Territory TX

Ford Territory TX_GX_wagon_(2018-09-17)_01.jpg) Toyota Kluger GX

Toyota Kluger GX

Water police

Water police boat

Water police boat

Honours and awards

Recognition of the bravery and diligent service of Western Australia Police Force personnel is through the awarding of honours and awards. Personnel are eligible to receive awards both as a part of the Australian honours system and the internal Western Australia Police Force honours system.

Australian honours system

Western Australia Police Force personnel are eligible for awards under the Australian honours system, including:

- Australian Bravery Awards – Cross of Valour, Star of Courage, Bravery Medal, Commendation for Brave Conduct, and Group Bravery Citation.

- Australian Police Medal – for distinguished service in the Office of Constable.

- Police Overseas Service Medal – for service with international peace-keeping organisations and/or service following requests for assistance from foreign governments.

- Humanitarian Overseas Service Medal – for humanitarian service overseas.

- National Emergency Medal – for sustained service during specified dates in specified places in response to nationally significant emergencies within Australia.

- National Police Service Medal – for 15 years ethical and diligent service in the Office of Constable.

- National Medal – for 15 years good conduct in operational service as members of specified organisations which serve or protect the community at hazard to themselves.

Western Australia Police Force honours system

- Cross for Bravery - Awarded to Western Australia Police Force personnel for an act of most conspicuous courage whereby the person placed themselves at peril and risk of significant personal injury or death.

- Western Australia Police Star – Awarded to Western Australia Police Force personnel who are killed or seriously injured whilst carrying out their primary functions on or off duty.

- Commissioner's Medal for Excellence - Awarded to Western Australia Police Force personnel who have consistently contributed to the achievement of the goals and objectives of the Western Australia Police.

- Western Australia Police Medal - Awarded to Western Australia Police Force personnel to recognise the sustained diligent and ethical service of its personnel.

- Special Commendation - Awarded to Western Australia Police Force personnel for an act of bravery whereby the person placed themselves at risk of personal injury, the action exceeding that might reasonably be expected.

- Commendation - Awarded to Western Australia Police Force personnel for meritorious conduct and devotion to duty under stressful conditions, whilst in the execution of his or her duty.

- Commissioner's Group Citation for Conduct - Awarded to a team/unit/district for displaying a significant level of commitment, dedication and professionalism to their duty in extenuating circumstances that reflects credit upon the Western Australia Police.

- Certificate of Outstanding Performance – Awarded for consistent outstanding performance by both individuals and teams at a District/Divisional and Regional/Portfolio level.

- Certificate of Appreciation – Awarded for significant contributions by individuals or community groups who, in partnership with Western Australia Police, have provided innovative, quality police services necessary to create a safer and more secure Western Australia.

Tactical Response Group

The Tactical Response Group (TRG) is a Police Tactical Group, a component of the Counter-Terrorism and State Protection Group (CT&SP TRG). It is a civilian body accountable under the state's police legislation (1892)[27] and criminal code.[28]

Since 1978, the Australian Government's National Anti-Terrorism Plan[29] has required each state police force to maintain a specialised counter-terrorist and hostage-rescue unit.

TRG officers are trained for high-risk situations and provide support to police and other agencies.[30] Such situations include dealing with armed offenders, attending sieges and civil-disorder incidents, protecting endangered witnesses, undertaking searches of premises, securing and escorting dangerous prisoners, heads of state, VIPs and internationally protected persons, as well as the state's counter-terrorist responsibility. Specialist positions include marksmen, bomb technicians and negotiators.[30][31]

The TRG is equipped with a wide range of less-lethal devices as well as specialist firearms and equipment for 'domestic' and counter-terrorist operations. Training includes tactical roping, fieldcraft, water borne operations, paramedical courses, the use of chemical, biological and radiological equipment, self-contained breathing apparatus and various weapons systems.[30] Specialised vehicles include 2 Lenco BearCat armoured police rescue vehicles and a forward-command vehicle for emergencies and other major events.[32]

The TRG has in recent times also expanded its capability to respond to counter-terrorist and high-risk incidents in a maritime environment including specialist divers, swimmers and the ability to board ships and oil/gas platforms.[33]

Police Air Wing

The Police Air Wing provides support services to gt frontline police, including deployment of police personnel, crime detection and prevention, search & rescue and medical transfers.

As of 2017 the fleet[34] comprises:

- Helicopters

- one twin-engine Eurocopter AS365 Dauphin N3 for special operations, transport and rescue;

- one twin-engine Kawasaki BK117 for general operations and backup capability

- Fixed-wing

- one single-engine Gippsland Aeronautics GA8 Airvan

- two single-engine Pilatus PC-12

The Air Wing has a primary base at Jandakot Airport, in addition to a PC-12 being based at Karratha Airport.

The Pilatus PC-12 is a single-engine turbo-prop aeroplane which can carry a maximum of eight passengers 1800 km (as far as Broome). It can cruise up to a height of 30,000 ft (9,100 m) and can travel at approximately 500 km/h. The PC-12's primary role is to transport staff statewide, but it can be utilised for search and rescue (SAR) and disaster relief efforts. The Cessna 182 is mainly used for surveillance and patrol work and can be fitted with a Leo400 FLIR unit. It is also used for inshore and land SAR searches.

The Kawasaki BK117 is a twin-engine helicopter, which has been upgraded to B2 specification. Purchased in 1990, and known as Polair 61, the aircraft’s role is police patrol, surveillance, search and rescue and officer deployment. It is fitted with a Star Safire III FLIR unit with downlink capabilities, Avalex digital recorder, Avalex moving map system, four monitors, Wulfsberg tactical radio, Nitesun searchlight and a double-lift 600 lb (270 kg) rescue winch. FLIR (Forward looking infrared) cameras track heat sources, such as a vehicle or human body in darkness and have a high-powered zoom video camera for daylight hours.

In September 2011, the Police Air Wing took delivery of a new Eurocopter AS365 N3 helicopter, known as Polair 62.[35] The cost of the new helicopter has been reported at $13 million for the helicopter, plus $9 million of equipment enhancements including Forward Looking Infra-Red cameras, winches, and live surveillance with downlink capabilities to the Police Operations Centre.[36]

Helicopter crash

On 8 May 1992, the police Polair One helicopter crashed while attempting to land on a sports oval for a public display in Kelmscott. The helicopter, an Aerospatiale AS355F1, was destroyed after a fire started in the engine bay following ground impact. The Bureau of Air Safety Investigation report determined "The helicopter probably entered a vortex ring state during the final approach". The pilot and crewman received minor injuries, and the two passengers serious injuries, as a result of the accident.[37]:p 1

Newman plane crash

On the 26 January 2001, four police officers lost their lives when their Cessna 310R plane crashed at night near the mining town of Newman. The plane was returning from Kiwirrkurra, on the edge of the Gibson Desert, when the aircraft's engines failed due to fuel starvation on the approach to Newman airstrip.[38]:p vii The crash was the single biggest loss of police lives in West Australian history, and the first involving a police aircraft.[39] The officers killed in the crash were: Senior Constable Donald Richard Everett 4600 – 49 years - Pilot of Karratha Police Airwing; Senior Constable Phillip Gavin Ruland 7877 – 32 years - Newman Police Station; First Class Constable David Adrian Dewar 9178 – 31 years - Newman Police Station; Constable Gavin Ashley Capes 10305 – 27 years - Newman Police Station. A remembrance ceremony is held each year by the people of Newman to honour this tragic event.[40]

Controversies

Prostitution murder in 1975

The murder of brothel keeper Shirley Finn around midnight on 23 June 1975 has long been suspected by some journalists to have resulted from a police conspiracy with political ramifications.[41] The circumstances, including the victim's alleged appearance in the canteen bar of the police headquarters at East Perth shortly before the killing,[42] have never been officially disclosed, despite several purported investigations and a royal commission.[43] Resulting from incessant public unrest over the matter, the WA coroner announced an inquest into the murder, commencing 11 September 2017.[44]

2002 Royal Commission

Throughout the 1990s there was widespread public concern about police activities and perceived shortcomings in internal integrity, resulting in development by the Labor parliamentary opposition of draft terms of reference for a proposed royal commission.[45] In 2002, the Kennedy Royal commission commenced to examine aspects of the behaviour and culture of the service. It concluded in 2004, finding that

...the full range of corrupt or criminal conduct from stealing to assaults, perjury, drug dealing and the improper disclosure of confidential information have been examined. [The Western Australian Police Service] has been ineffective in monitoring those events and modifying its procedures to deal with that conduct and to prevent its repetition.[46]:pp 1–2 The fact that there remain in WAPS a number of officers who participated in this conduct, and who not only refused to admit it, but also uniformly denied it with vehemence, is a matter of concern.[46]:p 4

In 2003, largely as a result of the findings of the Royal Commission, a permanent investigative Corruption and Crime Commission was established by the Government of Western Australia.

Deaths in custody

The 1987-1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody reported on the death of John Pat at Roebourne in 1983, and commissioner Elliott Johnston, QC, was critical of the lack of any disciplinary charges against five officers implicated in the violent death of a 16-year-old Aboriginal boy—calling this "a most unsatisfactory state of affairs".[47]

The 2002 royal commission investigated the February 1988 death of 18-year-old Stephen Wardle, who died whilst in custody in the East Perth lockup.[48] A particularly controversial aspect of the case was that 17 police witnesses declined to give evidence at the coronial inquiry "for the reason that their evidence might have had the tendency to incriminate them."[49]:pp 364–365 The commission's report noted:

"The royal commission has no authority under its terms of reference to go beyond the determination of whether or not there has been criminal or corrupt conduct by any police officer with respect to the death of Stephen Wardle. The evidence does not sustain any contention that there was corrupt or criminal conduct by any police officer or officers in relation to his death"[49]:p 367

Taser misuse

In November 2008, an academic and his wife were tasered by police during an arrest in Fremantle. The couple's lengthy requests for investigation and retribution were unsuccessful, so in December 2016, they successfully sued and were awarded over $1 million in damages.[50][51]

Two Rockingham senior police officers were sacked in 2010 for using Tasers on their colleagues during hooligan-style antics at the station over 18 months.[52] In September 2010 a video was released of an event in which numerous police officers tasered a man 13 times inside a police station. The incident, which occurred in August 2008, sparked worldwide publicity and renewed debate about the inclusion of tasers in the police force and officers' excessive use of it.[53] In April 2012, the state's Corruption and Crime Commission made several misconduct findings, recommended charges and said the policemen used "undue and excessive" force. The same man was also tasered 11 times on 6 September 2008 by Emergency Support Group officers from the Department of Corrective Services while being removed from a cell in the Perth Watch House.[54] In April 2013, it was reported that two senior officers were to be tried on criminal charges over the first incident.[55] At a hearing on 22 January 2014, the two officers were fined and given suspended jail terms for unlawful assault.[56]

In March 2018, a police officer was suspended for tasering a man seated at the wheel of his vehicle in Fremantle. The tasering had been deemed lawful by a police internal investigation but was described as unlawful, unreasonable and oppressive in a report by the state's Corruption and Crime Commission.[57]

Investigative abuses

In his judgment of a murder trial initiated in 2012 following the death of Corryn Rayney, Justice Brian Martin handed down a "not guilty" verdict and was critical of some police actions, stating that "there were instances of unacceptable conduct by some investigators ranging from inappropriate to reprehensible". He added that he had found "no evidence that lines of inquiry were not properly investigated".[58]:p1 Some five years before charges were laid, the senior sergeant in charge of the investigation had publicly named Lloyd Rayney as the force's "only suspect" and the "primary person of interest".[59] At the trial, which extended over three months, the judge found that "the State case is bereft of any evidence [establishing] a crime scene".[60]:p324 He concluded "The case for the State is beset by improbabilities and uncertainties. Crucial evidence is lacking and the absence of evidence tells strongly against the State. Endeavours by the State to fill critical gaps and explain away improbabilities are primarily no more than speculation without foundation in the evidence."[60]:p369 These findings were substantially upheld and vindicated by an appeal bench of three judges who unanimously dismissed the prosecutors' appeal, and upheld the trial judge's analysis and verdict.[61]

Justice Martin's criticism followed the exposure of a number of notorious cases of wrongful prosecution by Western Australia Police, including those of John Button, Darryl Beamish, the Mickelberg brothers and Andrew Mallard, resulting in reversal of long-standing convictions and large compensation payouts by government. In the case of Mallard, who spent 12 years in prison after an unjust conviction, a former WA assistant commissioner has concluded "Mallard is a very clear example of how police and prosecutorial misconduct can lead to a wrongful conviction and a miscarriage of justice...It is also another clear example of the difficulties in holding people to account."[62] A clemency petition drafted by the eminent barrister Malcolm McCusker, and lodged with the Western Australian attorney-general in 2012, alleged that key evidence was planted, withheld and misrepresented in police investigations leading to a 2009 murder trial in which Scott Douglas Austic was found guilty and sentenced to a minimum 25-year jail term.[63][64] After two successive attorneys-general declined to act on the petition, a fresh petition for clemency was lodged in March 2018 with a more receptive Attorney-General John Quigley, who also proposed legislation to allow people convicted of crimes to apply directly to the Court of Appeal.[65] Quigley, formerly an honorary life member of the Police Union of Western Australia, has subsequently become a fierce critic of the WA Police culture and hierarchy.[66]

An April 2014 report of the Western Australian Crimes and Corruption Commission cleared two police officers of any serious misconduct in the Corryn Rayney murder investigation. Their behaviour in threatening a female lawyer had been described as ranging from "inappropriate to reprehensible" by the trial judge. A second matter reviewed by the CCC related to "attempts by a third officer to encourage an independent pathologist involved in the case to change a report to better fit police evidence. That officer was found to have acted unreasonably."[67] In September 2014, lawyer and former state governor Malcolm McCusker supported calls for an independent review, and also a Corruption and Crime Commission investigation of "claims that police manufactured evidence to incriminate...Lloyd Rayney".[68]

On 12 April 2017, Gene Gibson, an illiterate and mentally impaired 25-year-old Aboriginal man, was released from prison by an appeals court after unjustly serving five years of a manslaughter sentence. Gibson, who was 20 when charged with a two-year-old unsolved murder, was interviewed for many hours by two junior detectives without benefit of an interpreter or legal counsel, which ultimately led to a fake confession and wrongful conviction.[69] Police Commissioner Karl O'Callaghan apologised for the investigative failure but disclosed that three officers "had not accepted blame and would now face an internal disciplinary process".[70] Similarly, after 10 years, the senior investigating officer in the Rayney murder case continued in 2017 to regard Lloyd Rayney as "the prime and only suspect" notwithstanding Rayney's comprehensive exoneration by the courts.[71] A defamation action brought by Rayney resulted in a record compensation award of over $2.6 million and legal costs of over $10 million.[72]

History of racism

On 12 July 2018, in a NAIDOC Week address, Police Commissioner Chris Dawson formally acknowledged a "history of racism or 'unconscious bias'" and publicly apologised to Aboriginal people for past mistreatment, urging his officers to treat Aboriginal people the same as they would a person of another race or background.[73][74][75]

See also

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Western Australia Police Force, About Us on official website. Retrieved 23 January 2018

- ↑ WA Police Force Annual Report, 2017

- ↑ "2016 Census QuickStats - Western Australia". abs.gov.au.

- ↑ "Premier of Western Australia & Cabinet Ministers". Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 23 January 2018.

- ↑ Western Australia Police Force, About Us on official website. Retrieved 23 January 2018

- ↑ 2016 Data in pictures—Greater Perth. Australian Bureau of Statistics, 27 June 2017

- ↑ Lieutenant-Governor Stirling's Proclamation of the Colony 18 June 1829 (UK)

- ↑ "Death of Captain Ellis, Principal Superintendent of the Corps of Mounted Police". The Perth Gazette and Western Australian Journal. WA. 15 Nov 1834. p. 390. Retrieved 17 Nov 2010.

- ↑ "Cooping the Convicts". Sunday Times (196). Western Australia. 29 September 1901. p. 8. Retrieved 17 February 2018 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ Jonescu, Emil Police custodial design is capricious and arbitrary: Formulating a specialised architectural strategy appropriate to short-term custodial facilities Curtin University 2008. Accessed 21 November 2013

- ↑ 2012 Annual Report, at official website.

- 1 2 Menagh, Joanna. WA's new police commissioner named as Australian Criminal Intelligence Commission boss Chris Dawson. ABC News, 1 August 2017. Accessed 11 September 2017

- 1 2 2013 Annual Report, at official website.

- ↑ "Gold Squad celebrates its 100th birthday". Government Media Office - Ministerial Media Statements. Archived from the original on 13 July 2009. Retrieved 25 June 2009.

- 1 2 WA Police Annual Report, 2017, 9 August 2017. On official website

- ↑ "Police Auxiliary Officer (Custody Support)". Police.wa.gov.au. 2017.

- ↑ "Police Auxiliary Officer (Protective Service Officer)". Police.wa.gov.au. 2017.

- ↑ "Police Auxiliary Officer (Protective Service Officer) - Training". Police.wa.gov.au. 2017.

- ↑ Northbridge police complex opens doors WAToday, 31 July 2013. Accessed 29 November 2013

- ↑ Relocation of Perth Police Station Official website

- ↑ Police Complex in need of more staff to handle demand ABC News, 11 September 2013

- ↑ Allen, Murray, WA Ombudsman "Police" (PDF). in Annual Report. 1999. , Chapter 3, page 17. 18 November 1999. Retrieved 17 March 2012

- ↑ Hughes, G., Wallace, R. "Cop watchdog's leash too tight". The Australian. 12 October 2007.

- ↑ "WA Police Commissioners: 1955-present". on WA Police official site

- ↑ "PM report". ABC Radio. 15 June 2004.

- ↑ http://www.parliament.wa.gov.au/hansard/hans35.nsf/16ab30a0303e54f448256bf7002049e8/3bb419a339c2425448256612000e833c?OpenDocument

- ↑ "Police Act (1892)".

- ↑ "W.A. Criminal Code".

- ↑ "Australia's National Anti-Terrorism Plan" (PDF).

- 1 2 3 "Tactical Response Group". (W.A. Police recruitment information site) Accessed 17 March 2012

- ↑ Talking it through—TRG sieges handled with care at NewsBeat (official police magazine) Spring 2010. Accessed 17 March 2012

- ↑ Perry, Philippa Police add specialist vehicles to existing fleet The West Australian, 19 October 2007, news article copy at Lenco Armoured Vehicles official website. Accessed 17 March 2012

- ↑ Water warriors—TRG tactical swimmer training at NewsBeat (official police magazine) Winter 2010. Accessed 17 March 2012

- ↑ "Police Air Wing". Western Australia Police.

- ↑ "Australian Aerospace announces sale of Dauphin Helicopter to WA Police". Australian Aerospace (Eurocopter).

- ↑ "Seven News, 29/09/2011". Seven Network.

- ↑ "Accident Investigation Report: B/921/1036" (PDF). Department of Transport and Communications - Bureau of Air Safety Investigation.

- ↑ Air Safety Investigation 200100348 at Australian Transport Safety Bureau. Report issued October 2002, ISBN 1 877071 15 3

- ↑ Newman, WA: Police Aircraft Crash. Australian Government - Attorney General's Department. 13 September 2006.

- ↑ Ten years on at Western Australia Police Force official website

- ↑ Maumill, Bob. Shirley Finn murder: more cops open up. WAtoday, 22 May 2015. Accessed 16 March 2017

- ↑ Shirley Finn cold case: Former cop reveals new details about 1975 murder of brothel madam. Sunday Times, 21 May 2015. Accessed 16 March 2017

- ↑ Norris, John Gerald (Commissioner) (1976). Report of the Royal Commission into matters surrounding the administration of the law relating to prostitution. Perth: Government of Western Australia

- ↑ Menagh, Joanna. Shirley Finn murder: Date set for inquest, 42 years after brothel madam's death. ABC News, Perth, 5 May 2017

- ↑ "Legislative Assembly Hansard record" (PDF). 11 October 2000. Page 1926 (pdf page 21)

- 1 2 Final Report Vol. 1, Part 1 of Kennedy Royal Commission, 30 January 2004

- ↑ John Peter Pat - 14.1.2 An Overview Royal Commission report, at Indigenous Law Resources, austlii.edu.au

- ↑ Weber, David "Royal Commission dubs WA police 'worst in nation'". ABC. 3 March 2004. at AM Transcript Archive

- 1 2 Final Report Vol. 1, Part 2 of Kennedy Royal Commission, 30 January 2004

- ↑ Hickey, Phil. "Perth couple 'tasered' eight years ago awarded more than $1 million in damages". WAtoday, 9 December 2016. Retrieved 26 March 2018

- ↑ Foster, Brendan. "CCC slammed for not probing Perth couple wrongfully tasered by police". The Age, 12 October 2017. Retrieved 26 March 2018

- ↑ Styles, Aja. "With Rayney in the dock police take out the trash. SMH, 10 December 2010. Accessed 28 April 2017

- ↑ "Possible criminal charges over taser use". ABC News. October 12, 2010.

- ↑ Bolton, Hayley. "CCC recommends police be charged over Kevin Spratt taser case". Perth Now, 16 April 2012

- ↑ Knowles, Gabrielle. "Spratt welcomes police taser charges" The West Australian, 11 April 2013. Accessed 28 April 2013

- ↑ AAP. "Perth Taser victim charged with assaulting police". The Australian, 24 January 2014. Retrieved 24 June 2014

- ↑ Hickey, Phil. "WA police officer stood aside following release of disturbing Fremantle taser footage". SMH, 21 March 2018. Retrieved 26 March 2018

- ↑ The State of Western Australia v Rayney Judgment summary, published by the Supreme Court of Western Australia 1 November 2012

- ↑ Caccetta, Wendy 'Prime suspect' cop Sen Sgt Jack Lee takes Rayney witness stand at Perth Now, 5 September 2012

- 1 2 The State of Western Australia v Rayney Full judgment, 1 November 2012,

- ↑ Appeal Judgment Summary at Supreme Court of Western Australia, delivered 23 September 2013

- ↑ Etter, Barbara. The Contribution of “Corruption” to Miscarriage of Justice Cases Address to the Corruption Prevention Network Forum in Sydney on 6 September 2012, p.16

- ↑ Banks, Amanda "Murder Doubts: Petition drafted by McCusker claims evidence was planted" Weekend West, 8 December 2012, p.1

- ↑ Media Report at Networked Knowledge website

- ↑ Hickey, Phil. "Lawyers lodge 'petition for clemency' for WA man jailed for murder he says he didn't commit". WAtoday, 9 March 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018

- ↑ Adshead, Gary. "Re-heated Cold War with WA Police shows John Quigley is just getting started". The West Australian, 27 March 2018. Retrieved 27 March 2018

- ↑ "Watchdog clears Rayney cops". The West Australian, 1 April 2014

- ↑ Egan, Colleen; Taylor, Grant. "McCusker calls for Rayney Inquiry", The Weekend West, 27–28 September 2014, p.1

- ↑ Taylor, Grant. "The morning two men's fates crossed". The West Australian, pp.4-5, 13 April 2017

- ↑ Clarke, Tim. "How Justice Failed". The West Australian, 13 April 2017, p.1

- ↑ Clarke, Tim. "Detective still believes his 'suspect' call". The West Australian, p.5, 6 April 2017

- ↑ Adshead, Gary; Clarke, Tim. "Lawyers fees swell Rayney bill to $13 million". The West Australian, 22 December 2017, p.3

- ↑ Carmody, James. "Police Commissioner Chris Dawson apologises to WA Aboriginal people for past mistreatment". ABC News, Perth, 12 July 2018

- ↑ Knowles, Gabrielle. "Police apology to Aboriginals". The West Australian, 12 July 2018, pp 1,9. (Temporary online version)

- ↑ Henriques-Gomes, Luke. "'Deeply sorry': Western Australia police chief apologises to Indigenous people", Guardian Australia, 12 July 2018

Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Western Australia Police. |

- Western Australia Police Force Annual Reports (Series from 2001)

- Western Australian Year Book 1974.

- Lieutenant-Governor Stirling's Proclamation of the Colony, 18 June 1829 (UK)

- Western Australia Police Service 2003

- WA Parliamentary Select Committee on the Western Australian Police Service Interim Report, June 1996

- Episodes in Western Australia's Policing History (1834-2002) on official website

External links

- Western Australia Police Force website

- Crime Stoppers WA

- Neighbourhood Watch

- Office of Crime Prevention

- Report on the Management of Misconduct by Western Australia Police at Western Australian Corruption and Crime Commission, 2 September 2011. Accessed 17 March 2012