Viroconium Cornoviorum

Remains of the public baths, known as "The Old Work" | |

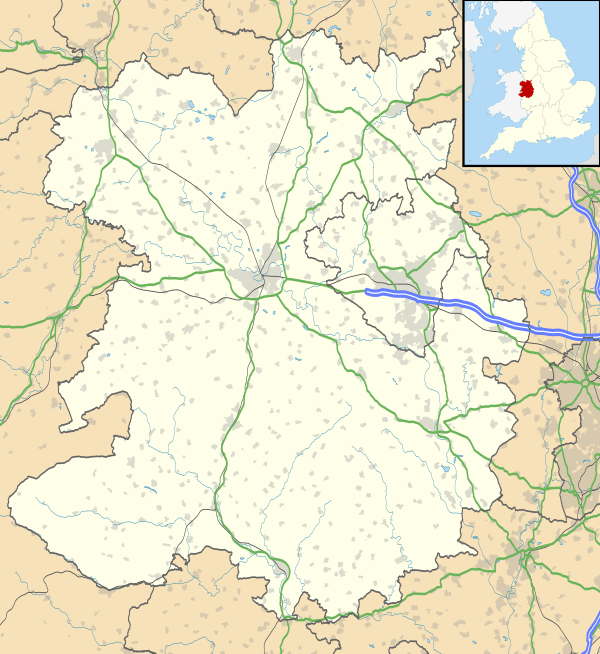

Shown within Shropshire | |

| Location | Wroxeter, Shropshire, England |

|---|---|

| Region | Britannia |

| Coordinates | 52°40′26″N 2°38′42″W / 52.674°N 2.645°WCoordinates: 52°40′26″N 2°38′42″W / 52.674°N 2.645°W |

| Type | Settlement |

- For the fictional city in the works of M. John Harrison, see Viriconium.

Viroconium or Uriconium, formally Viroconium Cornoviorum, was a Roman town, one corner of which is now occupied by Wroxeter, a small village in Shropshire, England, about 5 miles (8.0 km) east-south-east of Shrewsbury. At its peak, Viroconium is estimated to have been the 4th-largest Roman settlement in Britain, a civitas with a population of more than 15 000.[1] The settlement probably lasted until the end of the 7th century or the beginning of the 8th.[2] Extensive remains can still be seen.

Name

Viroconium is a Latinised form of a toponym that was reconstructed as Common Brittonic *Uiroconion "[city] of *Uirokū". *Uirokū (lit. "man-wolf") is believed to have been a masculine given name meaning "werewolf".[3][4]

The term "Cornoviorum" distinguishes the site as the Viroconium "of the Cornovii", the Celtic tribe whose civitas the settlement became. The original site of the Cornovian capital (also thought to have been named *Uiroconion) was a hillfort on the Wrekin.

History

Roman

The site at Wroxeter was strategically located near the end of the primary Watling Street Roman trunk road that ran across England from Dubris (Roman Dover). During the early years the site was a key frontier position lying on the bank of the Severn river whose valley penetrated deep into Wales and also lying on a route to the south leading to the Wye valley.

The site was first established in about AD 55 as a frontier post for a Thracian legionary cohort located at a fort near the Severn river crossing.[5] A few years later a legionary fortress (castrum) was built within the site of the later city for the Legio XIV Gemina during their invasion of Wales.

They were replaced in about 69 AD by the Legio XX Valeria Victrix which left to fight with Agricola in Scotland in 78 AD although the fortress may not have been completely abandoned until around 88 AD when it was taken over by the civilian settlement (canabae) that had grown up around the fort.

The local British tribe of the Cornovii probably had their original capital (also thought to have been named *Uiroconion) at the impressive hillfort on the Wrekin. When the Cornovii were eventually subdued their capital was moved to Wroxeter and given its Roman name.

When the legion left, an unfinished bath house remained in the centre of the town where the forum was later to be built. In the 90's AD the main street grid was being laid out based around the plan of the fort.[6]

The colonnaded forum was started in the 120s AD covering the unfinished bath house, and with the impressive dedicatory inscription to Hadrian found in excavations dating the completion to 130 AD. By 130, the town had expanded especially under Hadrian to cover an area of more than 173 acres (70 ha). It then had many public buildings, including thermae. Simpler temples and shops have also been excavated. At its peak, Viroconium is estimated to have been the one of the richest and the fourth largest Roman settlement in Britain with a population of more than 15,000.[1] Its wealth is surprising for what remained a frontier town and is perhaps explained by its access to Wales and to other trade routes.

Between 165-185 AD the forum was burnt down, including neighbouring shops and houses, and many shop contents were subsequently found in excavations. The forum was rebuilt with several modifications.

Middle Ages

Following the end of Roman rule in Britain around 410, the Cornovii seem to have divided into Pengwern and Powys. The later minor Magonsæte sub-kingdom of the Angles emerged in the area when Oswiu conquered Pengwern in 656.

Viroconium may have served as the early sub-Roman capital of Powys. The city has been variously identified with the Cair Urnarc[7] and Cair Guricon[8] which appeared in the Historia Brittonum's list the 28 civitates of Britain.[9]

N.J. Higham proposes that Viroconium became the site of the court of a sub-Roman kingdom known as the Wrocensaete, which was the successor territorial unit to Cornovia. Wrocensaete means the ‘inhabitants of Wroxeter’.[10]

Town life in Viroconium continued in the fifth century, but many of the buildings fell into disrepair. Between 530 and 570, when most Roman urban sites and villas in Britain were being abandoned,[11] there was a substantial rebuilding programme. The old basilica was carefully demolished and replaced with new timber-framed buildings on rubble platforms. These probably included a very large two-storey building and a number of storage buildings and houses. In all, 33 new buildings were "carefully planned and executed" and "skillfully constructed to Roman measurements using a trained labour force".[12] Who instigated this rebuilding programme is not known, but it may have been a bishop.[13] Some of the buildings were renewed three times, and the community probably lasted about 75 years until, for some reason, many of the buildings were dismantled.[14]

The site was probably abandoned peacefully in the second half of the seventh century or the beginning of the eighth.[15] The court of Powys is believed to have moved to Mathrafal sometime before 717 following famine and plague in its original location.

Reuse of building stone

According to archaeologist Philip A. Barker, the parish churches of Atcham, Wroxeter, and Upton Magna are largely built of stone taken from the buildings of Viroconium Cornoviorum.[16]

Wroxeter Roman City

Some remains are still standing, and further buildings have been excavated. These include "the Old Work" (an archway, part of the baths' frigidarium and the largest free-standing Roman ruin in England) and the remains of a baths complex. These are on display to the public and, along with a small museum, are looked after by English Heritage under the name "Wroxeter Roman City". Some of the more important finds are housed in the Music Hall Museum in Shrewsbury. Most of the town still remains buried, but it has largely been mapped through geophysical survey and aerial archaeology.

Reconstructed villa

A reconstructed Roman villa was opened to the public on 19 February 2011[17] to give visitors an insight into Roman building techniques and how the Romans lived.[18] A Channel 4 television series, Rome Wasn't Built in a Day,[19] showed how it was built using authentic ancient techniques. The builders were assisted by a team of local volunteers and supervised by archaeologist Dai Morgan Evans, who designed the villa.

Literature

- A. E. Housman referred to the town as "Uricon" in his poem "On Wenlock Edge" in A Shropshire Lad.

- Wilfred Owen saw archaeological digs in progress at Wroxeter and referred to it in his 1913 poem "Uriconium: an Ode".[20]

- "Viroconium" is a poem by the Shropshire novelist and poet Mary Webb.[21]

- Viroconium in its latter days is featured in Rosemary Sutcliff's 1961 historical novel Dawn Wind, part of her Roman-Britain series following the descendants of the lead character from The Eagle of the Ninth.

- Viroconium features in Mary Stewart's Merlin Chronicles The Crystal Cave, The Hollow Hills and The Last Enchantment.

Notes

- 1 2 Frere, Britannia, p.253

- ↑ White, Roger; Dalwood, Hal (March 1995). "Archaeological assessment of Wroxeter, Shropshire" (PDF). The Archaeology Data Service. p. 5. Retrieved 2016-04-15.

The occupation in the town seems to have ended peacefully, possibly in the late 7th or early 8th century

- ↑ Delamarre, Xavier (2012). Noms de lieux celtiques de l'europe ancienne. Arles: Editions Errance. p. 273. ISBN 978-2-87772-483-8.

- ↑ Wodtko, Dagmar (2000). Wörterbuch der keltiberischen Inschriften: Monumenta Linguarum Hispanicarum, Band V.1. Reichert-Verlag. p. 452. ISBN 978-3-89500-136-9.

- ↑ The Towns of Roman Britain, J.Wacher. Anchor Press 1974. p. 358 et seq.

- ↑ The Towns of Roman Britain, J.Wacher. Anchor Press 1974. p. 359

- ↑ Newman, John Henry & al. Lives of the English Saints: St. German, Bishop of Auxerre, Ch. X: "Britain in 429, A. D.", p. 92. James Toovey (London), 1844.

- ↑ Ford, David Nash. "The 28 Cities of Britain" at Britannia. 2000.

- ↑ Nennius (attrib.). Theodor Mommsen (ed.). Historia Brittonum, VI. Composed after AD 830. (in Latin) Hosted at Latin Wikisource.

- ↑ Higham, Nick J. (1993). The Origins of Cheshire. Manchester University Press. pp. 68–77. ISBN 0-7190-3160-5.

- ↑ Loseby, Simon T. (2000). "Power and towns in Late Roman Britain and early Anglo-Saxon England". In Gisela Ripoll, Josep M. Gurt. Sedes regiae (ann. 400–800). Barcelona. p. 339.

The likes of Verulamium and Wroxeter... are the best representatives of a 'post-Roman' phase of activity on town sites, a phenomenon which is not attested beyond the middle of the fifth century elsewhere.

- ↑ Barker 1998, pp. 121–128.

- ↑ Barker 1998, p. 125.

- ↑ Barker 1998, p. 136.

- ↑ Archaeological assessment of Wroxeter, Shropshire

- ↑ Barker, A. Philip (1977). Techniques of Archaeological Excavation. Routledge. p. 11.

- ↑ BBC News Shropshire – Reconstructed Roman villa unveiled at Wroxeter

- ↑ English Heritage – Properties

- ↑ Daily Mail: "Channel 4 series build Roman villa using ancient methods"

- ↑ Uriconium An Ode | The Wilfred Owen Association

- ↑ Representative Poetry Online – Mary Webb : Viroconium

References

- Aston, Michael; Bond, James (1976). The Landscape of Towns. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. pp. 45–48, 51–54. ISBN 0-460-04194-0.

- Anderson, J. Corbet. The Roman City of Uriconium at Wroxeter, Salop. – Illustrative of the History and Social Life of Our Romano-British Forefathers. London: J. Russell Smith, 1867.

- Atkinson, Donald. British Archaeological Society: Report on the Excavations at Wroxeter (the Roman City of Viroconium) in the County of Salop, 1923–1927. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1970.

- Barker, Philip, Ed. Wroxeter Roman City: Excavations 1966–1980. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1980.

- Barker, Philip, and Webster, Graham. From Roman Viroconium to medieval Wroxeter: recent work on the site of the Roman city of Wroxeter. Worcester: West Mercian Archaeological Consultants, 1990. ISBN 0-9516274-1-4

- Barker, Philip, and White, Roger. Wroxeter Roman City (English Heritage Guidebooks). Swindon, Wilts.: English Heritage, 1999. ISBN 1850746982

- Barker, Philip; White, Roger; Corbishley, Mike (1998). The Baths Basilica, Wroxeter: excavations 1966–90. Swindon: English Heritage. ISBN 1850745285.

- Bushe-Fox, J. P. Excavations on the Site of the Roman Town at Wroxeter, Shropshire, in 1912 (Society of Antiquaries of London. Research Committee. Report no. 1). Oxford: Society of Antiquaries, 1913.

- Bushe-Fox, J. P. Excavations on the Site of the Roman Town at Wroxeter, Shropshire, in 1913: Second Report (Society of Antiquaries of London. Research Committee. Report no. 2). Oxford: Society of Antiquaries, 1915.

- Bushe-Fox, J. P. Excavations on the Site of the Roman Town at Wroxeter, Shropshire, in 1914: Third Report (Society of Antiquaries of London. Research Committee. Report no. 4). Oxford: Society of Antiquaries, 1916.

- De la Bedoyere, Guy. (1991). The Buildings of Roman Britain.

- Ellis, Peter. The Roman Baths and Macellum at Wroxeter. Swindon, Wilts.: English Heritage, 2000. ISBN 978-1-85074-606-5

- Ellis, Peter, and White, Roger. 'Wroxeter Archaeology Excavation and Research on the Defences and in the Town – 1968–1992.' in Transactions of the Shropshire Archaeological and Historical Society, Vol. 78. Shrewsbury, Shrops.: Shropshire Archaeological Society, 2006. ISBN 0-9501227-8-5

- Fox, George E. A Guide to the Roman City of Uriconium at Wroxeter, Shropshire. Wellington, Shrops.: Shropshire Archaeological Society, 1927.

- Frere, S. S. Britannia: a History of Roman Britain. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul Ltd., 1987. ISBN 0-7102-1215-1

- Gaffney, V. L., and White, R. H. (2007). 'Wroxeter, the Cornovii, and the Urban Process: Final Report on the Wroxeter Hinterland Project 1994–1997', Journal of Roman Archaeology Supplementary Series, No. 68.

- Jackson, Kenneth (1970). "An Appendix on the Place Names of the British Section of the Antonine Itinerary". Britannia. 1.

- Kenyon, Kathleen M. Excavations at Viroconium, 1936–1937. Shrewsbury, Shrops. Shropshire Archaeological Society, 1937.

- Rivet, A. L. F., and Smith, Colin. (1979). The Place-Names of Roman Britain.

- Urban, Sylvanus. 'The Roman City of Uriconium.' Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Review, 1859. 206: 447–458.

- Webster, Graham. The Cornovii. London: Sutton, 1991. ISBN 0-86299-877-8

- Webster, Graham. The Legionary Fortress at Wroxeter: Excavations by Graham Webster, 1955–1985. Swindon, Wilts.: English Heritage, 2002. ISBN 9781850746850

- Webster, Graham. The Roman Army. London: Grosvenor Museum, 1973. ISBN 0-903235-05-6

- Webster, Graham, The Roman Imperial Army: Of the First and Second Centuries A.D. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1998. ISBN 0-8061-3000-8

- Webster, Graham, and Barker, Philip. Viroconium, Wroxeter Roman City. London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, 1966 & 1978. ISBN 0-11-670323-7

- White, Roger H.; Barker, Philip (1998). Wroxeter: Life and Death of a Roman City. Tempus. ISBN 978-0-7524-1409-6.

- White, Thomas. A Guide to the Ruins of Uriconium, at Wroxeter, Near Shrewsbury. Kessinger Publishing, 2009, ISBN 978-1-120-28973-5. BiblioBazaar, 2010, ISBN 978-1-143-79640-1. Nabu Press, 2010, ISBN 978-1-143-63705-6

- White, Thomas. Uriconium; A Historical Account of the Ancient Roman City, and of the Excavations Made Upon Its Site, at Wroxeter, in Shropshire. General Books, 2010. ISBN 1152210491

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Viroconium Cornoviorum. |

- BBC: Architectural Heritage

- Wroxeter Roman City: English Heritage

- Teachers'Resource pack on Wroxeter: English Heritage

- Viroconium Cornoviorum: Roman Legionary Fortress, British Tribal City – Roman-Britain.org

- Roman Fort and Bridge, Wroxter, Shropshire – Roman-Britain.org

- Wroxeter – Roman Britain's Fourth Largest City: Article by Dr. Gareth Evans

- Excavation report by Thomas Wright

- 1859 Article from Gentleman's Magazine

- Wroxeter, the Cornovii, and the Urban Process

- Report on Uriconium: Archaeological assessment of Wroxeter, Shropshire

- Esmonde Cleary, A., R. Warner, R. Talbert, T. Elliott, S. Gillies. "Places: 79741 (*Viroconium)". Pleiades. Retrieved 8 March 2012.