Calleva Atrebatum

Site plan of Calleva Atrebatum | |

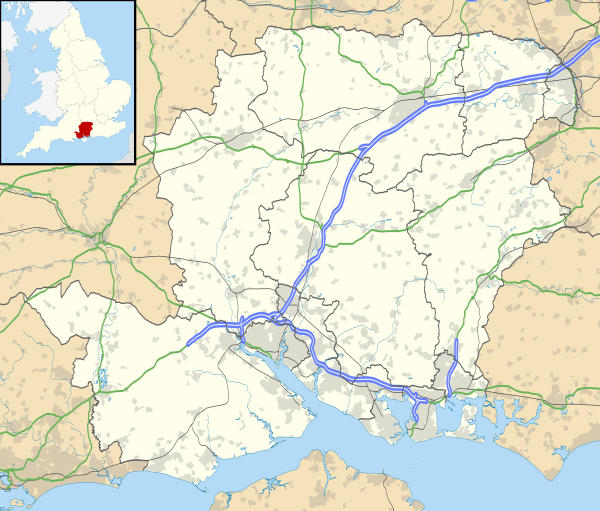

Shown within Hampshire | |

| Alternative name | Silchester Roman Town |

|---|---|

| Location | Silchester, Hampshire, England |

| Region | Britannia |

| Coordinates | 51°21′26″N 1°4′57″W / 51.35722°N 1.08250°WCoordinates: 51°21′26″N 1°4′57″W / 51.35722°N 1.08250°W |

| Type | Settlement |

| Area | Approximately 40 ha (99 acres) |

| History | |

| Builder | Atrebates tribe |

| Founded | Late 1st century BC |

| Abandoned | 5th to 7th century AD |

| Periods | Iron Age to Roman Empire |

| Site notes | |

| Management | English Heritage |

| Website | Silchester Roman City Walls and Amphitheatre |

| OS grid reference: SU639624 | |

Calleva Atrebatum ("Calleva of the Atrebates") was originally an Iron Age settlement, capital of the Atrebates tribe, and subsequently a town in the Roman province of Britannia.[1] Its ruins lie to the west of, and partly beneath, the Church of St Mary the Virgin, Silchester, in the county of Hampshire. The church occupies a site just within the ancient walls of Calleva although the village of Silchester itself now lies about a mile (1.6 km) to the west.

History

Unusually for a tribal capital in Britain, the Iron Age town was situated on the same site as the later Roman town although the layout was revised.

Iron Age

The Late Iron Age settlement at Silchester has been revealed by archaeology and coins of the British Q series link Silchester with the seat of power of the Atrebates. Coins found stamped with "COMMIOS" show that Commius, king of the Atrebates, established his territory and mint here after moving from Gaul.[2][3] The oppidum was situated on the edge of a gravel plateau, underlying the subsequent Roman town. The Inner Earthwork, constructed c. 1 AD, enclosed an area of 32 hectares, and a more extensive series of defensive earthworks was built in the wider area.

Small areas of Late Iron Age occupation have been uncovered on the south side of the Inner Earthwork [4] and around the South Gate.[5] More detailed evidence for Late Iron Age occupation was excavated below the Forum-Basilica. Several roundhouses, wells and pits occupy a north-east - south-west alignment, dated to c. 25 BC - 15 BC. Subsequent occupation, dated to c. 15 BC - AD 40/50, consisted of metalled streets, rubbish pits and palisaded enclosures. Imported Gallo-Belgic finewares, amphorae and iron and copper-alloy brooches show that the settlement was "high status". Also distinctive evidence for food was identified, including oyster shell, a large briquetage assemblage and sherds from amphorae which would have contained olive oil, fish sauce and wine.[6]

Further areas of Late Iron Age occupation have been uncovered by the Insula IX 'Town Life' Project which has revealed a substantial boundary ditch c. 40 - 20 BC, a large rectangular hall c. 25 BC - AD 10 and the laying out of lanes and new property divisions c. AD 10 - 40/50.[7] Archaeobotanical studies have demonstrated the import and consumption of celery, coriander and olive in Insula IX prior to the Claudian Conquest.[8]

Roman

After the Roman conquest of Britain in 43 AD the settlement developed into the Roman town of Calleva Atrebatum. It was slightly larger, covering about 40 hectares (99 acres), and was laid out along a distinctive street grid pattern. The town contained a number of public buildings and flourished until the early Anglo-Saxon period. A large mansio was situated in Insula VIII, near the South Gate, consisting of three wings arranged around a courtyard.[9] A possible nymphaeum was located near to the amphitheatre to the north of the walled city.[10]

Calleva was a major crossroads. The Devil's Highway connected it with the provincial capital Londinium (London). From Calleva, this road divided into routes to various other points west, including the road to Aquae Sulis (Bath); Ermin Way to Glevum (Gloucester); and the Port Way to Sorviodunum (Old Sarum near modern Salisbury).

The earthworks and, for much of the circumference, the ruined walls are still visible. The remains of the amphitheatre, added about AD 70-80 and situated outside the city walls, can also be clearly seen. The area inside the walls is now largely farmland with no visible distinguishing features, other than the enclosing earthworks and walls, with a tiny mediaeval church in one corner.[11][12] There is a spring that emanates from inside the walls, in the vicinity of the original baths, and which flows south-eastwards where it joins Silchester Brook.

Mediaeval

Silchester was finally abandoned in the 5th to 7th century, which is unusually late compared to other deserted Roman settlements.[13] The historian David Nash Ford identifies the site with the Cair Celemion of Nennius's list of the 28 cities of Sub-Roman Britain.[14] Most Roman towns in Britain continued to exist after the end of the Roman era, and consequently their remains underlay their more recent successors, which are often still major population centres. There is a suggestion[15] that the Saxons deliberately avoided Calleva after it was abandoned, preferring to maintain their existing centres at Winchester and Dorchester. There was a gap of perhaps a century before the twin Saxon towns of Basing and Reading were founded on rivers either side of Calleva. As a consequence, Calleva has been subject to relatively benign neglect for most of the last two millennia.[16]

Archaeology

.jpg)

Calleva Atrebatum was first excavated by the Rev. James Joyce who, in 1866, discovered the bronze eagle known as 'The Silchester Eagle' now in the Museum of Reading. It may originally have formed part of a Jupiter statue in the forum.

Calleva was partially excavated by the Society of Antiquaries of London between 1890 and 1909, and this excavation provided valuable information about civic life and daily life in the first centuries AD, as well as a map of the town. Whilst the excavation techniques of the time could deal with buildings with stone foundations, they were not capable of recovering timber construction that predominated in the 1st and 2nd centuries AD and which may have been destroyed.[17]

Molly Cotton carried out excavations on the defences from 1938-39.[18] Since the 1970s Michael Fulford and the University of Reading have undertaken several excavations on the town walls (1974–80),[19] amphitheatre (1979–85) [20] and the forum basilica (1977, 1980–86),[21] which has revealed remarkably good preservation of items from both the Iron Age and early Roman occupations.

From 1997 to 2014 [22][23] Reading University has made sustained and concentrated excavations in Insula IX. Results of the Late Roman [24] and Mid Roman phases have been published.[25] In 2013, excavations began in Insula III, investigating a structure identified by the Victorian excavations as a bathhouse.[26]

Access

Now primarily owned by Hampshire County Council and managed by English Heritage, the site of Calleva is open to the public during daylight hours, seven days a week and without charge.[27] The full circumference of the walls is accessible, as is the amphitheatre. The interior is farmed and, with the exception of the church and a single track that bisects the interior, inaccessible.

The Museum of Reading in Reading Town Hall has a gallery devoted to Calleva, displaying many archaeological finds from the various excavations.[28]

References

- ↑ Silchester: http://www.reading.ac.uk/silchester/about-silchester/sil-about-silchester-calleva.aspx

- ↑ G, Boon (1957). Roman Silchester. London: Max Parrish and Co.

- ↑ Creighton, John (2006). Britannia: the Creation of a Roman Province. Cambridge: Cambridge. pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Boon, G. 1969. Belgic and Roman Silchester: excavations of 1954-8 with an excursus on the early history of Calleva. Archaeologia 102: 1-81.

- ↑ Fulford, M. 1984. Silchester: Excavations on the Defences 1974-80. London: Society for Antiquaries. Britannia Monograph Series No. 5

- ↑ Fulford, M. and Timby, J. 2000. Late Iron Age and Roman Silchester: Excavations on the Site of the Forum Basilica, 1977, 1980-86. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. Britannia monograph Series No. 15

- ↑ Fulford, M; Clarke, A; Pankhurst, N; Lucas, S (2013). Silchester Insula IX: the 'Town Life' Project 2012. Reading: Department of Archaeology, University of Reading.

- ↑ Lodwick, Lisa (2014-09-01). "Condiments before Claudius: new plant foods at the Late Iron Age oppidum at Silchester, UK". Vegetation History and Archaeobotany. 23 (5): 543–549. doi:10.1007/s00334-013-0407-1. ISSN 0939-6314.

- ↑ Boon, George (1957). Roman Silchester: The Archaeology of a Romano-British Town. London: Max Parrish.

- ↑ Fulford, Michael (June 2018). "The Silchester 'Nymphaeum'". Britannia: 7–11. doi:10.1017/S0068113X18000235. ISSN 0068-113X.

- ↑ "Calleva Atrebatum - Roman Silchester". Discover Hampshire. Hampshire County Council. 2006-04-03. Archived from the original on 2007-09-30. Retrieved 2009-08-20.

- ↑ "Silchester Roman City Walls and Amphitheatre". English Heritage. Retrieved 2005-09-22.

- ↑ "History and Research: Silchester Roman City Walls and Amphitheatre". English Heritage. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ↑ Ford, David Nash. "[www.britannia.com/history/ebk/articles/nenniuscities.html The 28 Cities of Britain]" at Britannia. 2000.

- ↑ Kennedy, Maev (1999-04-09). "Burials 'show Roman city was cursed'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2008-12-17.

- ↑ "A Guide to Silchester". Silchester Insula IX. University of Reading. June 2009. Retrieved 2005-09-22.

- ↑ "History of the Excavations". Silchester Roman Town - A Guide to Silchester. University of Reading. 2004. Retrieved 2005-09-22.

- ↑ Cotton, M. A. 1947. Excavations at Silchester 1938-9. Archaeologia 92: 121-167.

- ↑ Fulford, M (1984). Silchester: Excavations on the Defences 1974-80. London: Society for Antiquaries. Britannia Monograph Series No. 5.

- ↑ Fulford, M (1989). The Silchester Amphitheatre: Excavations of 1979-85. London: Society for Antiquaries. Britannia Monograph Series No. 10.

- ↑ Fulford, M; Timby, J (2000). Late Iron Age and Roman Silchester: Excavations on the Site of the Forum Basilica, 1977, 1980-86. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. Britannia monograph Series No. 15.

- ↑ "The Insula IX Excavation". Silchester Roman Town - The 'Town Life' Project 1997-2002. University of Reading. 2004. Retrieved 2008-12-07.

- ↑ Fulford, Michael (2015-03-27). "Silchester: The Town Life Project 1997–2014: Reflections on a Long Term Research Excavation". Brindle, T., Allen, M., Durham, E., and Smith, A. (eds) 2015. TRAC 2014: Proceedings of the Twenty-Fourth Annual Theoretical Roman Archaeology Conference, Reading 2014. Oxford: Oxbow Books (2014): 114–121. doi:10.16995/trac2014_114_121. ISSN 2515-2289.

- ↑ Fulford, M; Clarke, A; Eckardt, H (2006). Life and Labour in Late Roman Silchester: Excavations in Insula IX since 1997. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. Britannia Monograph Series No. 22.

- ↑ Fulford, M; Clarke, A (2011). Silchester: City in Transition: the Mid-Roman Occupation of Insula IX c. A.D. 125-250/300: a Report on Excavations Undertaken Since 1997. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. Britannia Monograph Series no. 25.

- ↑ Fulford, M; Clarke, A; Pankhurst, N; Lambert-Gates, S (2015). Silchester: The 'Town' Life Project 2014 (PDF). Reading: Department of Archaeology, University of Reading.

- ↑ "PRICES AND OPENING TIMES FOR SILCHESTER ROMAN CITY WALLS AND AMPHITHEATRE". English Heritage.

- ↑ "Silchester Gallery". Reading Museum. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

Further reading

- Aston, Michael; Bond, James (1976). The Landscape of Towns. Archaeology in the Field Series. London: J.M. Dent & Sons Ltd. pp. 45–49. ISBN 0-460-04194-0.

- Clarke, A; Fulford, M; Rains, M; Shaffrey, R (2001). "The Victorian Excavations of 1893". Silchester Roman Town - The Insula IX Town Life Project. University of Reading. Retrieved 2005-12-20.

- Clarke, A; Eckardt, H; Fulford, M; Rains, M; Tootell, K (2005). "Late Roman Insula IX". Silchester Roman Town - The Insula IX Town Life Project. University of Reading. Retrieved 2005-12-20.

- Fulford, Michael; Clarke, Amanda; Eckardt, Hella (2006). Life and Labour in Late Roman Silchester: Excavations in Insula IX since 1997. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. Britannia Monograph Series no. 22.

- Fulford, Michael; Clarke, Amanda (2011). Silchester City in Transition: the Mid-Roman Occupation of Insula IX c. A.D. 125-250/300: a Report on Excavations Undertaken Since 1997. London: Society for the Promotion of Roman Studies. Britannia Monograph Series no. 25.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus; Lloyd, David (1967). Hampshire and the Isle of Wight. The Buildings of England. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 503–505.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Calleva Atrebatum. |

- Official website

- Details of archaeological open days

- Reading University web site on Silchester Roman Town

- Reading Museum web site on Silchester Roman Town

- City of the Dead: the Roman Town of Calleva Atrebatum, BBC article by Professor Michael Fulford.

- Pre-Roman Silchester Guardian article on discoveries in 2011-12 leading to reassessment of pre-Roman culture and history