Deities of Slavic religion

| Part of a series on |

| Slavic Native Faith |

|---|

|

| Historical Slavic religion |

|

Denominations Not strictly related ones: |

.jpg)

Deities of Slavic religion, arranged in cosmological and functional groups, are inherited through mythology and folklore. Both in the earliest Slavic religion and in modern Slavic Native Faith's theology and cosmology, gods are arranged as a hierarchy of powers begotten by the supreme God of the universe, Rod, known as Deivos in the earliest Slavic religion.[1] According to Helmold's Chronica Slavorum (compiled 1168–1169), "obeying the duties assigned to them, [the deities] have sprung from his [the supreme God's] blood and enjoy distinction in proportion to their nearness to the god of the gods".[2] The general Slavic term for "god" or "deity" is бог bog, whose original meaning is both "wealth" and its "giver".[3] The term is related to Sanskrit bhaga and Avestan baga.[4] Some Slavic gods are worshipped to this day in folk religion, especially in countrysides, despite longtime Christianisation of Slavic lands,[5] apart from the relatively recent phenomenon of organised Slavic Native Faith (Rodnovery).

Slavic folk belief holds that the world organises itself according to an oppositional and yet complementary cosmic duality through which the supreme God expresses itself, represented by Belobog ("White God") and Chernobog ("Black God"), collectively representing heavenly-masculine and earthly-feminine deities, or waxing light and waning light gods, respectively.[6] The two are also incarnated by Svarog–Perun and Veles, whom have been compared to the Indo-Iranian Mitra and Varuna, respectively.[7] All bright male gods, especially those whose name has the attributive suffix -vit, "lord", are epithets, denoting aspects or phases in the year of the masculine radiating force, personified by Perun (the "Thunder" and "Oak").[8] Veles, as the etymology of his name highlights, is instead the god of poetic inspiration and sight.[9] The underpinning Mokosh ("Moist"), the great goddess of the earth related to the Indo-Iranian Anahita, has always been the focus of a strong popular devotion, and is still worshipped by many Slavs, chiefly Russians.[10]

God of Heaven / absolute Rod

| Concept | Name variations | Description | Image and symbol[lower-greek 1] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –Rod –Deivos[lower-greek 2] |

–Rid (Ukrainian) –Rodu (Old East Slavic)[13] –Hrodo, Chrodo, Crodo, Krodo[14] –Crodone (Latinisation)[15] –Sud (South Slavic)[16] –Prabog, Praboh (Slovak)[16] |

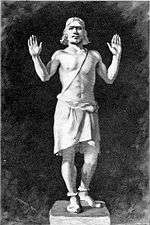

Absolute, primordial God of the universe and of all other gods. Supreme creator of all things and kins and their power of generation. Scholars have defined Rod as the "general power of birth and reproduction".[17] The root *rod means "birth", "origin", "kinship", "tribe" and "destiny". Sud, literally "Judge", is a South Slavic name for the supreme God, especially when conceived as the interweaving of destiny. Prabog is another name for the same concept, this time from the Slovak tradition, and literally means "Pre-God", "First-God", "Primordial God".[16]

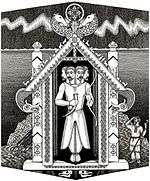

Rod, in its symbolisation of the generative process, has been compared to the Celtic Toutatis (cf. *teutā, "stock", "tribe"), and to the Latin Quirinus, the god of community and procreation (cf. *coviria, cūria). According to Émile Benveniste's definition of the Italic god of generation, it is the "god of the growth of the nation".[18] As supreme God, Rod has also been compared to the Latin Saturn. The iconography of Rod shows him governing the four elements: He stands on a fish, symbol of water; with one hand he heightens a wheel, symbol of the sun and of the cycles of the universe; with the other hand he holds a bucket of flowers, symbol of the blooming earth; and around his waist he has a fluttering linen belt, symbol of air.[19][20] |

Wheels and whirls[lower-greek 3] .jpg) |

Highest cosmological concepts

Basic information from Mathieu-Colas 2017.[16] Further information is appropriately referenced.

Supreme polarity

| Concept | Name variations | Description | Main attestations | Image and symbol[lower-greek 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belobog—Chernobog | ① –Bielobog, Byelobog[16] –Belibog[16] –Bielbog, Bjjelbog[16] –Gilbog[23] ② –Chernabog, Chernebog, Chernibog[16] –Czernabog, Czernibog, Czernobog[16] –Crnobog[16] –Zcerneboch[16] –Zernebog (Germanised Wendish)[24] –Tiarnaglofi, Tjarnaglofi[1] –Zlebog[23] –Pya[25] |

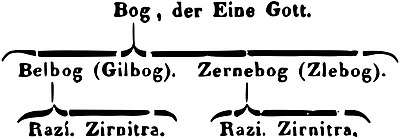

Literally, respectively, "White God" (cf. bieli, "white") and "Black God" (cf. cherni, "black"). They represent the oppositional and complementary duality which inheres reality, expressed for instance as light and darkness, day and night, male and female. Belobog incarnates as Svarog ("Heaven") and the multitude of his manifestations (cf. "threefold–fourfold divinity" hereinbelow), while Chernobog incarnates as Veles (also called Tjarnaglofi, i.e. "Black Head") and female deities.[26] All deities are manifestations of either Belobog or Chernobog, and in both categories they may be either Razi, rede-givers, or Zirnitra, dragon wizards.[27] Black gods were usually represented with the features of fierce animals.[25]

Hierarchy of the divine, with the two categories proceeding from the supreme God, as illustrated by Georg F. Creuzer and Franz J. Mone.[23] |

Baltic Slavs |  |

| Rod—Rozanica | –Rodzanica[16] –Rodzhanitsa, Rojanitsa[16] –Rozhdenica[16] –Rodjenica (Serbo-Croatian, Slovenian)[28] –Razivia, Raziwia[29] –Rodiva, Rodiwa[29] –Deva, Dewa, Dzewa[29] –Baba[30] –Krasopani[29] –Udelnica (north Russian)[31] |

Literally "God and the Goddess", it is a conceptualisation of the supreme polarity as male–female, formed by the masculine form plus the feminine form of the root *rod; it implies the union of the supreme God with matter to shape reality. The feminine form is frequently spelled plural, interpreting Rozanica as the collective representation of the three goddesses of fate. Rozanica is an ancient mother goddess, and her name literally means the "Generatrix" or "Genitrix".[32] In kinships, while Rod represents the forefathers from the male side, Rozanica represents the ancestresses from the female side. Through the history of the Slavs, the latter gradually became more prominent than the former, because of the importance of the mother to the newborn child.[33]

She is also called Deva, meaning the "Young Lady" or simply "Goddess", regarded as the singular goddess of whom all lesser goddesses are manifestations;[34] Baba, meaning the "Old Lady", "Crone", "Hag";[30] and Krasopani, meaning the "Beautiful Lady". She has been compared to the Greek Aphrodite and the Indic Lakshmi,[29] but especially to the Roman Juno, female consort of the supreme God, whom collectively represented the Junones, the Norse Disir, the spirits of female lineages who determined fate.[33] The north Russian name Udelnica means "Bestower" (of fate).[31] The ancient Slavs offered bread, cheese and honey to Rod–Rozanica.[33] |

East Slavs, Russes |  |

| Sud—Sudenica | –Sudenitsa[16] –Sudica[31] –Sudjenica (Serbo-Croatian)[31] –Sojenica, Sujenica (Slovenian)[31] –Sudzhenica (Bulgarian)[31] –Sudicka (Bohemian)[31] –Naruchnica (Bulgarian)[31] –Orisnica, Urisnica, Uresica (Bulgarian)[31] |

Sud literally means "Judge"; God interpreted as the interweaving of fate. Sudenica, literally meaning "She who Judges", is his female counterpart manifesting as the three goddesses (Sudenicy) who determine the fate of men at their birth. They are often presented as Sud's three daughters.[16] The Bulgarian name Orisnica and its variants come from the Greek word ὁρῐ́ζων, horízōn, meaning "determining". Sudenicy are sometimes represented as good-natured old women, and other times as beautiful young women with sparkling eyes, clad in white garments, with their heads covered in white cloths, adorned with gold and silver jewels and precious stones, and holding burning candles in their hands. In other traditions they are planly attired, with only a wreath of flowers around their heads.[31] | South Slavs | - |

| Vid–Vida | ① –Wid –Vit, Wit –Sutvid[35] ② –Wida –Vita, Wita |

The supreme polarity as male–female is documented among South Slavs also as Vid–Vida.[35] The root *vid or *vit refers to "sight", "vision".[36] Vid, as highlighted by the name variant Sutvid, may be identified as Svetovid.[35] Like Rodiva, also her manifestation Vida has been compared to the Latin Juno.[37] Vida is identified as the celestial and rainy aspect of the great goddess, contrasted with the terrestrial and dry Zhiva (cf. herebelow).[38] She is entitled "Empress of Heaven", associated with the theme of the tree of light.[39] | South Slavs, Serbs/Croats | - |

| Zhibog—Zhiva | ① –Zibog –Siebog[16] –Sibog, Shibog –Jibog, Gibog ② –Ziva[16] –Ziwa, Zhiwa[16] –Sieva, Sieba (Germanised Wendish)[24] –Siva, Shiva[16] –Siwa, Shiwa[16] –Jiva, Giva[16] –Zivena, Zhivena[16] –Ziwena[40] –Zywie (Polish)[41] –Sisja[42] |

Conceptualisation of the supreme polarity as life. Zhibog literally means "Life God", "Life Giver", while Zhiva means "She who Lives". They are conceived as either siblings or spouses, and gods of love, fertility and marriage. Zhibog is represented with a cat head.[25] Zhiva has been compared to the ancient Roman Bona Dea, Ceres and Ops.[36] She is the opposite facet of Morana, the goddess of death (cf. "great goddesses" hereinbelow).[16] She has been studied as the terrestrial and dry aspect of the great goddess, contrasted with the celestial and rainy Vida.[38] | East Slavs, Russes |  .png) |

Threefold–fourfold divinity and fire-god

| Concept | Name variations | Polarity | Description | Main attestations | Image and symbol[lower-greek 1] | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Triglav | –Triglov, Triglaf[16] –Triglau[16] –Tryglav, Tryglaw –Tribog[43] –Trojan[44] |

M | Triglav literally means "Three-Headed". The concept represents three gods who personify the three worlds (Prav-Yav-Nav), or Heaven, earth and the underworld,[26] and sovereignty over the three elements of air, water and soil.[16] The three heads are Svarog, Perun and Svetovid or Veles. Triglav is often represented riding a black horse.[45] As the union of the three dimensions of reality represented as a mountain or tree, Triglav was defined as summus deus ("summing god") by Ebbo. Triglav has also been defined as a conceptualisation of the axis mundi.[46] Adam of Bremen described the Triglav of Wolin as Neptunus triplicis naturae (i.e. "Neptune of the three natures/generations") attesting the colours that were associated to the three worlds: white for Heaven, green for earth and black for the underworld.[47] Triglav also represents the union of the three dimensions of time: past, present and future as a whole.[48] | Baltic Slavs |  | ||||

| Svarog | –Swarog –Jarog, Rarog[49] –Tvarog[50] –Svarogu (Old East Slavic)[51] –Shafarjk[52] –Schwayxtix, Swayxtix (Germanised Wendish)[53] –Swetich[52] –Swieticz[52] –Zwaigzdze[52] |

M | Svarog literally means "Heaven" (cf. Indic Svarga), father of Xors Dazhbog and Svarozhich or identical with them.[16] He is compared to the Greco-Roman Saturn–Chronos, the time god.[26] Scholars also consider him cognate with the Iranian Verethragna or Varhran, the Indic Indra Vṛtrahan, the Armenian Vahagn.[49] He is associated with military, smithery, and with fire (Ognebog), both that of the household and that of the sun (Xors Dazhbog).[50] The Indo-European root of the name is *swer ("to speak"), related to *wer ("to close", "defend", "protect"). Jarog and Rarog are alterations of the name, the second applied to a bird god of later folk religion. Indeed, Svarog and his Indo-Iranian cognates are considered able to manifest as wind, birds or other animals, and have the role of the dragon-slayer in mythology.[49] He is the power which makes bright and virile. In some traditions Svetovid, Gerovit, Porevit and Rugievit are considered his four manifestations.[50] | East Slavs, Russes | .jpg)    | ||||

| Perun | –Parun[16] –Peron (Slovak)[16] –Porun[54] –Piorun (Polish)[16] –Peraun (Czech)[16] –Parom (Slovak, Moravian)[54] –Perusan (Bulgarian)[54] –Prone, Prohn, Pyron, Perone (Pomeranian)[54] –Peryn, Perin (Novgorodian)[55] –Prono[56] –Percunust (Germanised Wendish)[24] |

M | Perun literally means "Thunder" but also "Oak", and he is the son of Svarog, worshipped as the god of war. He is related to the Germanic Thor and other Indo-European thunder gods.[16] In Christianised folk religion he is equated with Saint Elias.[57] He is the opposite polarity of Veles, the male god of the earth. In some traditions, he has a mother, Percunatele (a goddess inherited from Baltic traditions), and a sister Ognyena ("She of the Fire").[58]

Perun is the personification of the active, masculine force of nature, and all the bright gods are regarded as his aspects, or different phases during the year. His name, which comes from the Indo-European root *per or *perkw ("to strike", "splinter"), signifies both the splintering thunder and the splintered tree (especially the oak; the Latin name of this tree, quercus, comes from the same root), regarded as symbols of the irradiation of the force.[59] This root also gave rise to the Vedic Parjanya, the Baltic Perkunas, the Albanian Perëndi (now denoting "God" and "sky"), the Norse Fjörgynn and the Greek Keraunós ("thunderbolt", rhymic form of *Peraunós, used as an epithet of Zeus).[60] Perun has also been compared to the Indic Brahma, and together with Potrembog (Vishnu) and Peklabog (Shiva), as a component of the Triglav interpreted as the equivalent of the Indic Trimurti.[61] Traditional iconography shows Perun with a head surrounded by ten beams of light, with two faces—that of a man on the front side, and that of a lion on the back side–, and holding a plough in front of him.[62] |

- |  | ||||

| Svetovid | –Svetovit, Swetowit[63] –Swatowit[16] –Sventovit[51] –Svantovit, Swantowit[64] –Svantevit[51] –Sviatovit, Swiatowit[63] –Swiantowid[51] –Swetobog, Swentobog, Swatobog[65] –Wit, With, Wet[66] |

M–F | Four-headed god of war, light and power. A major temple dedicated to him was located at Cape Arkona. Svetovid and its variants literally mean "Lord of Power" or "Lord of Holiness" (the root *svet defining the "miraculous and beneficial power", or holy power),[67] but it has also been translated as "Worldseer". He may have been a West Slavic version of Svarog. In some traditions, the white northward head is Svarog himself, the red westward head is Perun, the black southward head is Lada, and the green eastward head is Mokosh, thus two are male and two female. In other traditions, the eastward head is Rugievit, the southward head is Porevit, the westward head is Gerovit, and the northward head is Svarog himself. They represent the four directions of space, the four seasons of time, and the four Russias of sacred geography.[68] Svetovid has been described as the complete representation of the axis mundi, symbolising the union of the four directions of space and the three dimensions of reality (Heaven, earth and the netherworld).[69] He is also represented riding a white horse.[45] | Baltic Slavs |   | ||||

| –Ognebog –Svarozhich |

① –Ogne, Ogni –Ognevik ② –Svarogitch, Svarojitch[16] –Svarazhich[70] –Svarozhyn (Kashubian)[71] –Tvarozhich[71] |

M | Ognebog literally means "Fire God", and is the Slavic equivalent of the Indic Agni,[72] personification of the both the celestial and terrestrial fire, and of the sacrificial flame, considered as the energy proceeding from Svarog and connecting back to him.[73] He is often equated with Simargl. Svarozhich, literally meaning "Son of Heaven" (Svarog), is always identified as the god of fire, and was the tutelary deity of the Baltic Slavs.[16] It may be an epithet of the various heavenly gods, among whom Perun, Svetovid or Xors Dazhbog, or be Svarog himself.[71] | - |  |

Sun-god and moon-god

Both the sun god and the moon god, Dazhbog and Jutrobog, are often qualified as "Xors"[lower-greek 4] (![]()

| Concept | Name variations | Polarity | Description | Main attestations | Image and symbol[lower-greek 1] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Xors Dazhbog | –Dazhdbog[16] –Dadzbog (Polish)[73] –Dajbog, Dojbog (Serbo-Croatian)[81] –Dambog[16] –Dabog, Daba (Serbo-Croatian)[73] –Dazibogu (Old East Slavic)[26] |

M | Dazhbog is the sun god, son of Svarog, winner of darkness, warranter of justice and wellbeing. Mathieu-Colas interprets Dazhbog as meaning "Wealth Giver" (cf. dati, "giving").[16] He changes from a young man to an old man as he travels through the sky; he has two daughters accompanying him, the two Zvezda ("Morning Star" and "Evening Star"), and has a brother, the bald moon god (Jutrobog).[26] | East Slavs, Russes |

| ||

| Xors Jutrobog | ① –Jutrebog[82] –Juthrbog[16] –Yutrobog –Jutrenka, Gitrenka[83] –Jutrovit, Jutrowit[84] ② –Mesyats[1] –Myesyats[16] –Messiatz[16] |

M | Jutrobog is the moon god,[16] but also the moon light at daybreak, whence the meaning of his name, "Morning God" or "Morning Giver". The city of Jüterbog, in Brandenburg, is named after him.[85] The theonym may refer to Yarilo as the good of the moon. The name Mesyats literally means "Moon". The moon god was particularly important to the Slavs, regarded as the dispenser of abundance and health, worshipped through round dances, and in some traditions considered the progenitor of mankind. The belief in the moon god was still very much alive in the nineteenth century, and peasants in the Ukrainian Carpathians openly affirm that the moon is their god.[1] | West Slavs, Wends |  |

Goddesses

Basic information from Mathieu-Colas 2017.[16] Further information is appropriately referenced.

Great goddesses

| Concept | Name variations | Description | Main attestations | Image and symbol[lower-greek 1] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –Devana –Ciza –Zizilia |

① –Dewana, Diewana[16] –Diewen[86] –Debena[16] –Diiwica, Dilwica (Serbo-Croatian, Polish)[16] –Dziewanna, Dziewonna (Polish)[16] –Dziewica[86] –Dziewitza, Dziwitza[86] –Dziewina[86] –Dewin, Dewina[86] –Devoina[86] –Zewena[86] –Ziewonia[86] ② –Cisa[40] –Cica, Cyca[40] –Sisa, Ziza[40] –Zeiz (German)[87] ③ –Didilia, Didilla (South Slavic)[16] –Dzidziela, Dziedzilia, Zizilia (Polish)[88] –Zyzlila[86] –Dzydzilelya, Dzidzilelya (Polish)[16] |

Goddess of hunting and of the forests. Her name is etymologically related to the Roman Diana, and she is also functionally correlated with the Greek Artemis.[89] Another name of Devana is Ciza, whose etymology is traced to the Slavic root *cic or *cec, meaning the mother's breast.[40] Under the name variations Dzydzilelya, Zizilia or Didilia, she is known as the goddess of love and wedding, fertility and infancy among West Slavs; this name is explained as meaning "she who pampers babies" (cf. dziecilela), and with these functions she is compared to the Roman Venus or Lucina.[16] Devana has been regarded as a manifestation of the great goddess Rodiva–Deva, especially in her terrestrial fertile aspect, and as such compared to the Germanic Nerthus.[90] | West Slavs, Czechs/Slovaks |  | ||

| –Perperuna –Dodola |

① –Preperuna, Peperuna[91] –Preperuda, Peperuda, Pepereda[91] –Preperuga, Peperuga[91] –Peperunga, Pemperuga[91] –Peperouna (Greek)[91] –Perperona (Albanian)[91] –Pirpiruna (Aromanian)[91] –Perperusha, Preperushe[92] –Prepelice[92] –Prporusha (Dalmatian)[93] ② –Doda[16] –Dudola, Dudula (Serbo-Croatian)[91] –Didjulja, Didjul, Djudjul (Bulgarian)[91] |

Goddess of rain, wife of Perun, in this function also identified as Dodol, the god of the air.[16] According to Vyacheslav Ivanov and Vladimir Toporov, Dodola is a southern equivalent of the West Slavic Zizilia,[94] as evidenced by some Bulgarian variations of her name (cf. Didjulja).[91] The name Perperuna is the feminine form of Perun with a reduplicated root *per, while Dodola means "rumbling", "thundering a bit".[95] The root of the name relates her to the Norse goddess Fjörgyn. Her rituals, still practised among South Slavs in modernity, show similarities with the Vedic hymns to Parjanya.[96] | South Slavs, Serbians West Slavs, Poles |

| ||

| Kupala | –Kupalnica, Kupalnitsa[16] –Kupalo (masculine)[16] –Solntse[97] |

Goddess representing the mighty sun of summer solstice, but also goddess of joy and water. She is celebrated on Kupala Night with rituals of purification through water and fire. She is seldom represented as male, and the name Kupala or Kupalo is etymologically related to the verb kupati, "to wet". Solntse (simply "Sun", but often translated Phoebus) is another name of the goddess of the fully bright sun. The cult of Kupala was Christianised as that of John the Baptist.[16] | - |  | ||

| Lada | –Lado, Ladon (masculine)[16] | Polyfunctional great goddess of the earth, harmony and joy, symbolising youth, spring, beauty, fertility and love. Mother of twins (named either Dido and Dada or Lel and Polel) and mother or wife of Lado (Mathieu-Colas says that among Slavs there is evidence that Lado is the same as Lada conceived as male; he is represented as a phallic god).[16] She is the female counterpart of Svarog.[26] According to scholars, among whom Boris Rybakov, Lada is cognate with the Greek Leda, the Greco-Roman Leto–Latona, and is possibly the same as Rod's supreme counterpart Rodzanica.[21] Lel and Polel are related to Leda's twin sons Castor and Pollux.[98] | Slavs–Balts | .1998%D0%B3.29%2C6%D1%8520%2C2.jpg) | ||

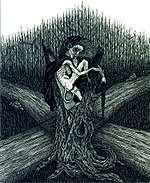

| Marzanna | –Mara –Morana, Morena[16] –Marowit, Merovit[84] –Maslenitsa –Marzyana (Polish) –Baba Yaga |

Rural goddess who grows sprouts, but at the same time goddess of winter and death. Her opposite is Zivena (i.e. Zhiva).[16] Marovit is another name of Marzanna or her male counterpart, symbolising the dying sun; the root *mar means "weakness", "ruin" and "death".[84] Baba Yaga is also the goddess of death, both young and old, associated both with birds and snakes. According to Leeming, who takes Marija Gimbutas as source, she is clearly cognate with the Indic Kali as the deathly aspect of the great goddess of Old Europe.[26] | West Slavs, Poles |  | ||

| –Mokosh –Mat Syra Zemlya |

① –Makosh[16] –Mokosi[16] –Mokosha, Mokysha, Mokusha[16] ② –Mata Syra Zjemlja[26] –Mati Syra Zemlya –Mat Zemlya –Zeme –Matka[26] |

Mother goddess personifying the wet earth, associated with female works (notably weaving) and harvest.[16] She is also the goddess of corn, the "Corn Mother". Her name literally means "Wetness", "Moist", and she is also known by the title Mat Syra Zemlya ("Damp Mother Earth") or Matka.[26] In association with Perun she becomes dry and fiery, Ognyena, personifying the woman in her higher and faithful aspect; whereas in association with Veles she becomes dry and frozen, an aspect of Zhiva personifying the woman in her lower and unfaithful aspect.[99] With Christianisation she was transformed into the Black Madonna, very popular in Poland, and in Saint Paraskevi.[100] Her Indo-Iranian equivalent is Aredvi Sura Anahita.[10] | East Slavs, Russes |   |

Other goddesses

| Concept | Name variations | Description | Main attestations | Image and symbol[lower-greek 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chislobog | –Zislobog, Ziselbog (Germanised Wendish)[101] –Kricco (Wendish)[102] |

Literally "Number Giver". She is the goddess of time calculation, of the lunar month and of the moon's influences. Represented as a youthful female with a crescent moon on her forehead. Kricco is her Wendish name and she was also worshipped as the protectress of the crops.[103] | - |  |

| Karna | - | Goddess of the funerals, personifying tears. She is compared to the Indic Karna.[16] | - |  |

| Kostroma | - | Goddess of spring and fertility.[16] She is the female counterpart of Kostromo, and she is connected with grain. Her celebration falls on 29 June, the Christian Feast of Saints Peter and Paul, during which a village maiden representing the deity would be ritually bathed in a stream and then worshipped for an evening of feasting and dancing. The divine twins Kostroma and Kostromo are one aspect of a fourfold fertility deity, whose other aspects are Lada–Lado, Yarila–Yarilo, and Kupala–Kupalo.[104] | East Slavs, Russes |  |

| Lelia | - | Goddess of spring and mercy, daughter of Lada.[16] According to Boris Rybakov, Lelia is the closest equivalent of the Greek Artemis, being associated with the Ursa Major constellation.[21] | - |  |

| Matergabia | –Matergabiae[16] | Matergabia literally means "Fire Mother". She is the goddess of the hearth, comparable to the Roman Vesta. Her Baltic cognate is Gabija.[16] | Slavs–Balts |  |

| Ognyena | –Ognjena (Marija)[58] –Onennaya (Mariya) (Russian)[105] –Marija Ognjenica[106] –Marija Glavnjenica[106] –Ognevikha |

Ognyena literally means "She of the Fire", "Fiery", and is the goddess of the celestial fire, sister of Perun. She is another personification of the great goddess of the earth (Mokosh) when she is dried up, and thus elevated, by celestial fieriness.[58] She is frequently named Ognyena Maria ("Fiery Mary") in the South Slavic tradition, since, in Christianised folk religion, Ognyena has been syncretised with the figures of both Margaret the Virgin and the Virgin Mary, regarded as the sisters of Saint Elias. She is celebrated on 30 July (Julian 17 July).[105] | South Slavs |  |

| Ozwiena | - | Goddess of the echo,[16] and generally of voice and oral communication. | - | - |

| Baba Slata | –Zlata Baba[16] –Slotaia Baba –Zolotaya Baba, Zolotaja Baba[16] –Zolstoia Baba[16] –Baba Zlatna[107] –Baba Korizma[36] –Baba Gvozdenzuba[39] |

Her name literally means "Golden Old Lady". She is worshipped among Finno-Ugric populations along the Ob River, but also among Slavs.[16] She has two other aspects, Baba Korizma ("Lent Old Lady") and Baba Gvozdenzuba ("Iron-Toothed Old Lady"). She has been compared to the Greek Hecate.[36] | Finno-Ugrics Slavs |

.png) |

| Uroda | - | Goddess of ploughed land, of agriculture.[16] | West Slavs, Slovaks | .jpg) |

| Ursula | –Ursala[16] –Orsel[16] –Horsel[16] –Urschel (German)[16] |

Goddess of the moon associated with the Ursa Minor constellation. She is compared to the German goddess Urschel and the Greek Artemis.[16] | - |  |

| Veliona | –Velonia[16] –Vielona, Vielonia[16] –Veliuona[16] –Velu Mate[16] –Velnias (Lithuanian)[16] –Velns (Latvian)[16] |

Goddess of death, warden of the souls of the ancestors. Though the name is feminine, the polarity of the god/dess is not sure. Among the Balts, Velnias or Velns is male, but there is also a Velu Mate ("Mother of the Souls").[16] Her name shares the same root of Veles, *wel.[108] | Slavs–Balts | _(4).jpg) |

| Vesna | - | Goddess of spring.[16] | - |  |

Other gods and goddesses

Basic information from Mathieu-Colas 2017.[16] Further information is appropriately referenced.

Other important male gods

| Concept | Name variations | Description | Main attestations | Image and symbol[lower-greek 1] | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chur | - | God of boundaries and of the delimitation of properties.[16] He is comparable to the Roman Terminus. | - |  _Germany_(Bad_Muskau).jpg) | ||

| Dogoda | - | God of the west wind.[16] | - | - | ||

| Erisvorsh | –Erishvorsh, Erivorsh[16] –Varpulis, Warpulis[16] |

God of the storm, wind and thunder. He is an aspect, name, or associate of Perun.[16] | - |  | ||

| Flins | –Flyns –Flyntz[25] |

God of death[16] who may be a Wendish name of Veles, although the iconography is rather different. He is sometimes represented as a skeleton with a lion upon his shoulder, holding a burning torch in his hand, and placing a foot on a large pebble. In other cases he is represented as an old man, with the same attributes of the skeleton, except for a flint instead of a pebble.[25] His cult was widespread in Lower Silesia, Lusatia and Saxony.[109] | West Slavs, Wends | |||

| Ipabog | - | Ipabog is the god of hunting.[16] The name may mean "Movement Giver", as its root may be related to the Wendish hybawy and hyban, which mean the idea and action of movement, linked with the Gothic yppa, "to uppen", "heighten". The god was conceived as in constant motion, and he was represented as clothed, with deer horns on his head.[110] | - | |||

| Koliada | –Kolyada, Koljada[16] –Koleda[16] –Ovsen[16] –Tausen |

God representing the young, winter sun returning after solstice.[16] The name is related to kolo ("wheel", "cycle"), and indirectly to Greek kalanda, later Latinised as calendae.[111] | Slavs–Balts |

| ||

| Kresnik | –Krsnik[16] –Skrstnik[112] –Vesnik[112] –Kurent[112] |

God of fire and of the sun.[16] He is a young, solar warrior hero and a benevolent god of fertility, but also a god of rebirth who "waits ... in a mountain cavern for the hour of his awakening and return to true life".[112] | South Slavs, Slovenes |  | ||

| Morskoy | –Morskoi[16] –Morskoy Czar[16] –Czar Morskoy[16] |

He is the god of the sea. His name literally means "Emperor (cf. Latin Caesar) of the Sea", and he is compared to the Greco-Roman Poseidon–Neptune.[16] | East Slavs, Russes |  | ||

| Nemiza | –Nemisa, Nemisia[113] –Nimizia[113] |

God who cuts the thread of life, sometimes represented as a male with four beams around his head, one wing, and on his chest a dove with outstretched wings, and sometimes represented as a naked female with an eagle by her side gazing up to her. Nemiza was regarded both as a calamity for bringing death, and as a beneficial figure for introducing the soul to a new life.[25] | West Slavs, Wends |  | ||

| –Ny –Peklabog |

① –Nija, Nyja[16] ② –Pekla[114] –Pekelnybog (Prussian)[114] –Pekollo, Pekollos, Pikollos[114] –Peklos, Poklos[114] –Peklo, Pieklo (Bohemian)[114] –Pekelle[114] –Pikiello[114] –Patello, Patelo, Patala[114] –Peklenc –Pekelnik –Pekelnipan –Lokton |

Ny is the god of the underworld who acts as psychopomp, that is to say the guide of the souls into the underworld.[16] He is associated with subterranean fire and water, snakes and earthquakes. Peklabog or Pekelnybog is another name of the god of the underworld, and he has been compared to the Indic Shiva.[114] Etymologically, the word peklo means "pitch", and after Christianisation, its meaning became that of "hell", often personified as the Devil, and pekelnik any being of hell. (cf. Finnic Perkele). | West Slavs, Poles |   | ||

| Porevit | –Porewit, Porevith[16] –Porovit, Puruvit[16] –Porenut[16] –Proven, Prove (Germanisation)[115] –Turupit, Tarapita[51] |

Porevit is depicted with five faces, one of which is on his chest,[16] but also with a shield and a lance.[62] A cult centre of Porevit was at Garz, in Rügen.[16] The name means "Lord of Power", with the root *per defining the masculine power of generation. He is an aspect or other name of Perun, as also highlighted by some sources which link the name to the Finnic Tharapita.[116] Germanised as Proven or Prove he is attested as the tutelary deity of Oldenburg,[16] and this name is considered a corruption of Prone.[54] When regarded as an aspect of Svetovid, he represents south and summer.[51] | Baltic Slavs | .jpg) | ||

| Posvist | –Poswist, Poshvist[16] –Pogvist, Pohvist[16] –Pozvizd |

God of the wind, otherwise called "Russian Star". His name literally means "Whistler" or "Blower".[16] | East Slavs, Russes |  | ||

| Pripegala | –Prepeluga[92] | Mathieu-Colas identifies this deity as cognate with the Greco-Roman Priapus.[16] According to other scholarly studies it is a name corruption, made by the Archbishop of Magdeburg, of Prepeluga, another name of Perperuna Dodola.[92] | Baltic Slavs | - | ||

| –Radegast –Potrembog |

① –Radigast, Redigast[16] –Radigost[16] –Radegaste[16] –Radhost[16] ② –Potrebbog[117] –Potrimbo, Potrembo[117] –Potrimpo, Potrimpos[117] |

God of honour, strength and hospitality. He was the tutelary deity of the Redarians.[16] He has been studied as the Slavic equivalent of the Indic Vishnu. The deity is associated with the snake, and the root of Potrembog, another name of Radegast, may be the same of potrebny, "needing".[117] Traditional iconography shows him with a double face, that of a man on one side and that of a lion on the other side, with a swan on his head and a bull head on his chest; otherwise, he is represented as a naked man, with a bird with outstretched wings on his head, a shield with a bull head before his chest, and a halberd in his right hand.[62] | Baltic Slavs |  _18.jpg) | ||

| –Rugievit –Karevit |

① –Rugiewit[16] –Rujevit[16] –Rugiwit[16] –Ruevit[16] –Riuvit[16] –Rinvit[16] ② –Karewit[16] |

Warrior god and tutelary deity of Rügen. Mathieu-Colas explains his name as "Lord of Rugia";[16] other scholars explain it, instead, as "Roaring/Howling Lord" (cf. Old East Slavic rjuti, "to roar", "howl").[118] Like Porevit, he had a cult centre in Garz. Another name or aspect of Rugievit is Karevit (probably "Lord of Charenza").[16] Rugievit himself is perhaps an aspect of Svetovid, representing east and autumn. He is represented with seven heads.[51] | Baltic Slavs |   | ||

| –Simargl –Pereplut |

–Semargl[16] –Simarg[16] –Simarigl[16] –Simariglu (Old East Slavic)[26] –Sinnargual[16] –Simnarguel[16] |

Chimerical or draconian figure compared to the Persian Simurgh.[10] He is frequently associated with Pereplut,[16] an East Slavic name variation of Perperuna Dodola,[95] which would make him the same as Perun. He may be a god of fortune and drinking, abundance and vegetation, or more commonly a tutelary deity of sailors.[16] | East Slavs, Russes |  | ||

| Stribog | –Strybog[16] –Strzybog (Polish) –Stribogu (Old East Slavic)[26] |

Stribog literally means "Wealth Spreader", and he is the god of winds and storms. He is often coupled with Dazhbog, the "Wealth Giver". Stri is the imperative mood of the Slavic root *sterti, from the Indo-European root *ster, which means "to stretch", "spread", "widen", "scatter" (cf. Latin sternō).[119] | East Slavs, Russes |  | ||

| –Veles | –Veless, Weless[16] –Voloss, Woloss[16] –Woles[120] –Wlacie[120] –Wel[120] –Walgino (Polish)[16] –Skotibog, Skotybog[121] –Zembog[16] |

Veles is the chthonic god of cattle—whence his other name, Skotibog, which literally means "Cattle Giver"[121]—, but also master of the forest and of wild animals, and god of commerce.[122] He is also the god of poetic inspiration and sight, as highlighted by his name which comes from the Indo-European root *wel, which implies sight and magical ability.[108] The Book of Veles is dedicated to him. Walgino is the name of the cattle god in Polish tradition,[16] though Weles is more common nowadays. Also known as the "Horned God", Veles is a male god of the earth, incarnating the "Black God" of dual theology. As such he is the opposite of the heavenly manifestations of the "White God" (Svarog and his sons, but especially Perun).[26] An alternative name of Veles that was used by Baltic Slavs is Tjarnaglofi ("Black Head", identifying him as Chernobog).[89] The name Zembog literally means "Earth Giver"[16] and may refer to Veles. He is compared to the Indic Varuna, the Celtic Esus and the Norse Ullr amongst others.[123] | East Slavs, Russes |  | ||

| –Yarilo –Gerovit |

① –Yarylo –Jarilo, Jarylo, Jaryla[16] ② –Gerowit[16] –Gierovit[124] –Yarovit –Jarovit, Jarowit[125] –Jerowit, Dzarowit[26] –Harovit, Harowit[126] –Herovit[118] –Harevit[124] |

God of spring, sexuality and fertility,[16] and also of peace.[83] His original name was Gerovit or Jarovit, which literally mean "Strong/Wroth Lord" (from the root *ger or *jar, "strong" or "wrathful")[16] or "Bright Lord" (cf. Russian jaryj, "bright"), while Yarilo is a modern Russian popular variation.[127] He is also regarded as a warrior god and was the tutelary deity of Wolgast.[16] As an aspect of Svetovid he represents west and spring, and has been compared to the Greek god of Eastern origin Adonis–Dionysus both representing youth, death and resurrection.[26] Kostrubonko is another East Slavic god, or another name of Yarilo, with the same functions of spring and fertility, death and resurrection.[16] Under the name Myesyats ("Moon"), Yarilo is identified as the moon god. | - |   |

Other twosomes and threesomes

| Concept | Name variations | Polarity | Description | Main attestations | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dido–Dida | –Lado–Lada[16] | M–F | Divine twins, just siblings or even spouses, sons either of Lado and Lada, or just of Lada, or rather identical with Lado and Lada themselves. Dido is attested in some traditions as the husband of goddess Lada.[89] | Slavs–Balts | - |

| Dolya–Nedolya | –Dola–Nedola[16] | F | Goddess of fate, personification of the fate bestowed upon a man at birth. She is described as a planly dressed woman able to turn herself into various shapes.[128] When she is positive she is named Dolya, when negative she turns into Nedolya.[16] The good Dolya protects her favourite day and night, serving him faithfully from birth to death; she takes care of his health and wealth, protects his offspring and makes his properties blossom. The evil Nedolya, also called Likho in later folklore, neglects the man to whom she is assigned, and thinks only for herself. It is considered impossible to get rid of Dolya, either in her good or evil aspect.[129] | East Slavs, Russes |  |

| Srecha–Nesrecha | –Sretcha–Nesretcha[16] | F | She is a South Slavic concept similar to the East Slavic Dolya–Nedolya.[16] The relation between Srecha and Dolya has been described as the same between the Latin concepts of fors and fortuna, or sors and fatum. Unlike Dolya, a man may get rid of Srecha. She is represented as a beautiful woman spinning a golden thread, bestowing welfare upon the man to whom she is assigned. As misfortune, Nedolya, she is depicted as an old woman with bloodshot eyes.[130] | South Slavs | - |

| Zorya | –Zoria[16] –Zaria, Zarya[16] –Zora[16] –Zroya[16] –Zimtserla[16] |

F | Zorya is the goddess of beauty,[131] virgin associated with war and with Perun.[16] Her name literally means "Light" or "Aurora", and she manifests as three goddesses, described as daughters of Dazhbog and sisters of Zvezda, with whom they are often conflated:[16]

|

- | .jpg) |

| Zvezda | –Zwezda (Polish)[16] | F | Zvezda literally means "Star", and refers to the planet Venus. It is the name of two sister goddesses, often conflated with Zoria, who represent the two phases of the planet Venus:[16]

|

- |  |

Tutelary deities of specific places, things and crafts

In Slavic religion, everything has a spirit or soul (![]()

Deities of waters, woods and fields

Basic information from Mathieu-Colas 2017.[16] Further information is appropriately referenced.

| Concept | Name variations | Polarity | Description | Main attestations | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bereginia | –Beregynia, Berehynia (Ukrainian)[16] –Przeginia (Polish)[57] |

F | Tutelary deity, or deities, of waters and riverbanks (cf. Old East Slavic beregu, "bank, shore").[16] In modern Ukrainian Native Faith she has been heightened to the status of a national goddess "hearth mother, protectress of the earth".[133] Some scholars identify Bereginia as the same as Rusalka.[134] In Old Church Slavonic, the name was prĕgyni or peregyni, and they were rather—as attested by chronicles and highlighted by the root *per—spirits of trees and rivers related to Perun. The interpretation as female water spirits, bregynja or beregynja, is an innovation of modern Russian folklore.[135] She is cognate with the German goddess Fergunna and the Gothic Fairguni.[136] | East Slavs, Russes |  |

| Vodianoy | –Vodianoi, Vodianoj[16] –Vodnik (Bohemian)[137] –Vodeni Mozh (Slovenian)[137] –Bagiennik –Bolotnik |

M | Vodianoy is a tutelary deity, or are tutelary deities, of waters (cf. voda, "water").[16] He is represented as an old man with a high cap of reeds on his head and a belt of rushes around his waist. To ingratiate themselves with him, Slavic fishermen sacrificed butter in water while millers sacrificed sows.[138] | - |  |

| –Boginka |

–Bogunka (Polish)[16] –Russalka[16] –Navia, Nawia –Navje, Mavje (Slovenian)[139] –Navi, Navjaci (Bulgarian)[139] –Nejka, Majka, Mavka (Ukrainian)[139] –Nemodlika (Bohemian, Moravian)[16] –Latawci (Polish)[140] –Vila, Wila[141] –Samodiva, Samovila, Vila, Iuda (Bulgarian)[141][142] |

F | Boginka literally means "Little Goddess". Always described as plural, boginky ("little goddesses"), they are tutelary deities of waters.[16] They are distinguished into various categories, under different names, and they may be either white (beneficent) or black (maleficent).[143]

The root *nav which is present in some name variants, for instance Navia and Mavka, means "dead", as these little goddesses are conceived as the spirits of dead children or young women. They are represented as half-naked beautiful girls with long hair, but in the South Slavic tradition also as birds who soar in the depths of the skies. They live in waters, woods and steppes, and they giggle, sing, play music and clap their hands. They are so beautiful that they bewitch young men and might bring them to death by drawing them into deep water. They have been compared to the Greek Nymphs.[144] Samodiva/Samovila are a type of woodland spirits known to Bulgaria, of which samodiva is the more commonly used, while samovila is more specific to Western Bulgaria. The words diva has the meanings of "wild", "rage", "rave", "divinity" whereas vila means "spun" or "spinning" (such as tornado or a hailstorm spinning). The "samo-" prefix means "self-". Iuda/Iuda-Samodiva generally refers to an evil spirit (or to Judas if used as a given name). These samodivas/samovilas are said to share a strong resemblance to Roman Nymphs (as well as to a lesser extent to fairies, elves and other similar spirits). They are described as playful woodland humanoid beings clad in white and wearing wreaths that can be beneficent or maleficent to men and women alike, depending on how they perceive being treated. They are sometimes young and beautiful, other times old and revolting. They are said to be found in woods, mountains, near fairy rings, near water sources where they bathe (especially near dictamnus albus ) or in contrast dwelling in graveyards, dangerous places and to build invisible cities below the clouds when they are associated with malice. They can sometimes be attributed to: have wings, transform in various animals such as wolves, send ravens/crows as messengers, ride white-gray deer or bears, shoot arrows. The cult of the Vila was still practiced among South Slavs in the early twentieth century, with various offerings. [145] [142] |

- |  |

| –Leshy –Borewit |

① –Leshak[146] –Leshuk (Belarussian)[16] –Leszy, Lesny (Polish) –Lesnoy, Lesnoi, Lesnoj[146] –Lesovoy, Lesovoi, Lesovoj[146] –Lesovik[147] ② –Barowit[148] –Borovoy, Borovoi, Borovoj[149] –Borovik[149] –Boruta[148] |

M | Leshy is the tutelary deity of forests, with a wife (Leshachikha) and children (leshonky). Another name of the god is Borewit or Boruta, coming from the Slavic root *bor which denotes dark woods. Due to the similarity of the name with Porewit, a relation between the two has been hypothesised.[148] He is represented as an old man with long hair and beard, with flashing green eyes.[147] To secure his protection, people who lived near woods sacrificed cows and salted bread to him.[150] He may manifest in the form of animals, such as bears, wolves and hares.[147] Other names include Berstuk and Zuttibur (also rendered Swiatibor[87]) among the Wends, Modeina and Silinietz among the Poles, and Sicksa.[16] Cf. the Greek Pan. | - |  |

| –Polevoy –Poludnica |

① –Polevoi, Polevoj[16] –Polevik[16] –Belun (Belarusian)[151] –Datan[16] –Lawkapatim[16] –Laukosargan (Prussian)[16] –Tawals[16] ② –Poludnitsa, Poludnitza[16] –Polednica[152] –Poludniowka, Przypoludnika (Polish)[152] |

M–F | Tutelary deity of fields (cf. pole, "field"). Among Poles, the god of the fields is also known by the names Datan, Lawkapatim, or Tawals. Poludnica is his female form; her name is etymologically related to poluden or polden, not only related to fields but also, literally, "midday". She is represented either as an airy, white woman or as an old woman with horse hoofs and a sharp sickle in her hand.[152] The name Lawkapatim reflects the Prussian Laukosargas.[16] | - |

Deities of settings and crafts

| Concept | Name variations | Polarity | Description | Main attestations | Image and symbol[lower-greek 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| –Domovoy –Domania |

① –Domovoi, Domovoj[16] –Domovik (Ukrainian)[153] –Did, Didko, Diduch (Ukrainian)[153] –Ded, Dedushka[154] –Dedek (Czech)[153] –Djadek (Silesian)[153] –Shetek, Shotek (Bohemian)[153] –Skritek[153] –Shkrat, Shkratec (Slovenian)[155] –Shkrata, Shkriatek (Slovak)[155] –Skrzatek, Skrzat, Skrzot (Polish)[155] –Chozyain, Chozyainushko (Russian)[156] –Stopan (Bulgarian)[156] –Domovnichek, Hospodarichek (Bohemian)[156] ② –Domovikha[16] –Kikimora[16] –Marukha[16] –Volossatka[16] |

M–F | Domovoy is the household god, warden of the hearth. The Indo-European root *dom is shared by many words in the semantic field of "abode", "domain" (cf. Latin domus, "house").[16] Domania is sometimes present as his female counterpart,[16] but he is most often a single god.[157] According to the Russian folklorist E. G. Kagarov, Domovoy is a conceptualisation of the supreme Rod itself as the singular kin and its possessions.[98] Domovoy are deified fountainhead ancestors, and all other household deities with specific functions are their extensions.[158] Domovoy may manifest in the form of animals, such as cats, dogs or bears, but also as the master of the house or a departed ancestor of the given kin.[159] In some traditions they are symbolised as snakes.[156] They have been compared to the Roman Di Penates, the genii of the family, and they were worshipped by the Slavs as statuettes which were placed in niches near the house's door, and later above the ovens.[153]

Other household gods are ① Dvorovoy (tutelary deity of courtyards[16]), ② Bannik ("Bath Spirit", tutelary deity of the sauna who corresponds to the Komi Pyvsiansa[16]) and ③ Ovinnik ("Threshing Barn Spirit"),[160] ④ Prigirstitis (known for his fine hearing), and the goddess ⑤ Krimba among Bohemians. Another household deity is the lizard-shaped Giwoitis.[16] |

- | .jpg) |

| Dugnay | –Dugnai[16] | F | Tutelary deity of bread and bakery.[16] | Slavs–Balts |  |

| Julius | - | M | Tutelary deity of Wolin.[16] He is the deified Julius Caesar, who was worshipped as the supposed founding ancestor of the city. The name of the city in medieval Latin texts is Iulin, allegedly a derivative of Julius. In Wolin there was a wooden pillar with an old lance hewn into it; the lance allegedly belonged to Julius Caesar. According to Dynda, this Julius' pillar was another representation of the axis mundi, of the Triglav.[161] | Baltic Slavs | .jpg) |

| Krugis | –Krukis[16] –Kriukis[16] |

M | Tutelary deity of blacksmithery (and pets).[16] | Slavs–Balts |  |

| Pizamar | - | M | Tutelary deity of Asund, in Rügen.[16] | Baltic Slavs | - |

| Podaga | - | M | Tutelary deity of hunting and fishing. Attested as the tutelary deity of Plön.[16] According to some scholars, the name Podaga might have originated as a distortion by metathesis of the name Dazhbog, Dabog, in Helmold's chronicles.[81] | Baltic Slavs | - |

Deities of animals and plants

| Concept | Name variations | Polarity | Description | Main attestations | Image |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kirnis | - | M | Tutelary deity of cherries.[16] | Slavs–Balts | .jpg) |

| –Kremara –Darinka |

- | M–F | Kremara is the tutelary god of pigs.[16] Under the name Priparchis, he is identified as a tutelary deity specifically of young, suckling pigs.[16] Darinka is instead an aspect of the great goddess associated with pigs, seen as a symbol of the earth's abundance. She is attested in folk traditions of Vojvodina and has been compared to the Roman Bona Dea and Ceres, themselves connected with holy swines.[162] | West Slavs, Poles South Slavs, Serbs |

|

| Kurwaichin | - | M | Tutelary deity of lambs.[16] | West Slavs, Poles |  |

| Pesseias | - | M | Tutelary deity of pets.[16] | - | |

| Ratainitsa | –Ratainicza[16] –Ratainycia (Lithuanian)[16] |

M | Tutelary deity of horses.[16] | West Slavs, Poles |  |

| Zosim | - | M | Tutelary deity of bees.[16] | - |  |

Germanic deities and others

The Wends, including those who dwelt in modern-day northern and eastern Germany and were later Germanised, or other never-Germanised West Slavs, also worshipped deities adopted from Germanic religion, as documented by Bernhard Severin Ingemann. However, Germanic gods never rose to prominence over Slavic ones in Wendish religion.[24]

| Concept | Name variations | Polarity | Description | Origin | Image and symbol[lower-greek 1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woda[163] | –Vohda[164] | M | Woda (the Germanic Wotan-Odin) was worshipped as a god of war and leadership, in relation to the Slavic verb *voditi, "to lead". He was also associated with rune wisdom and with Vid (Svetovid), as the supreme God, the "moving force behind all things";[39] runes were called vitha by the West Slavs, which is a genetive of *vid or *vit meaning "image" or "side", "facet" (referring to the multifaceted essence of the supreme God).[164] | Germanic | .jpg) |

| Balduri[24] | - | M | - | Germanic |  |

| –Hela[24] –Mita[165] |

–Myda[25] | F | Hela, the death goddess, is represented with a lion head with an outstretched tongue. As Myda, an aspect or another name of hers, she is represented as a crouching dog.[25] | Germanic |  |

| Morok | - | M | Morok, literally "Darkness" in Russian, is a concept that has been deified in modern Slavic Native Faith (Rodnovery). He is the god of lie and a deceit, ignorance and errors. At the same time, he is a keeper of ways to the truth, hiding such ways to those who pursue truth for vanity and selfishness. He has a twin brother, Moroz ("Frost"), and they switch into one another at will. | 21st-century Rodnovery |

Gallery

Illustrations of Slavic deities, in "Historia Lusatica", Acta Eruditorum, Calendis Aprilis 1715.

Illustrations of Slavic deities, in "Historia Lusatica", Acta Eruditorum, Calendis Aprilis 1715. Illustrations of Slavo-Saxon deities, in Saxonia Museum für saechsische Vaterlandskunde, 1834.

Illustrations of Slavo-Saxon deities, in Saxonia Museum für saechsische Vaterlandskunde, 1834.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 In the tables, black symbols are those with historical attestation and transmitted through folk religion; otherwise, red symbols are some variants in use in modern Rodnovery, especially in Russia. Some of the latter are found, for instance, in: Kushnir, Dimitry (2014). Slavic Light Symbols. The Slavic Way. 5. ISBN 9781505805963.

- ↑ Deivos, cognate with the Proto-Indo-European *Dyeus, is the most ancient name of the Slavic supreme God of Heaven (cf. Sanskrit Deva, Latin Deus, Old High German Ziu and Lithuanian Dievas).[11] This name was abandoned when Slavic religion, in line with Proto-Indo-Iranian religion, shifted the meaning of the Indo-European descriptor of heavenly deities (Avestan daeva, Old Church Slavonic div, both going back to Proto-Indo-European *deiwos, "celestial") to the designation of evil entities, and in parallel began to describe gods by the term for both "wealth" and its "givers" (Avestan baga, Old Church Slavonic bog). At first it was replaced with the term for "clouds", cf. Old Church Slavonic Nebo.[12]

- ↑ Boris Rybakov identifies all wheel, whirl and spiral symbols as representing Rod in its many forms, including the "six-petaled rose" and the "thunder mark" (gromovoi znak),[21] the latter most often associated to Perun. The contemporary design of the symbol called kolovrat, the eight-spoked wheel used as the collective symbol of Rodnovery, was already present in woodcuts produced in the 1920s by the Polish artist Stanisław Jakubowski under the name słoneczko ("little sun").[22]

- ↑ Also spelled Hors,[74] Chors, Chers, Churs, Chros,[75] and Kh- variants, and Xursu (in Old East Slavic).[26]

References

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Gasparini 2013.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, p. 5.

- ↑ Mathieu-Colas 2017; Rudy 1985, p. 5.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, pp. 5, 14–15.

- ↑ Leeming 2005, pp. 359–360; Rudy 1985, p. 9.

- ↑ Gasparini 2013; Hanuš 1842, pp. 151–183; Heck 1852, pp. 289–290.

- ↑ Ivakhiv 2005, p. 214.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, pp. 17–18.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, pp. 24–25.

- 1 2 3 Rudy 1985, p. 9.

- ↑ Gasparini 2013; Rudy 1985, p. 4.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, pp. 4–5, 14–15.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, p. 31.

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, p. 116; "...Krodo, dem Slawen-Gotte, dem grossen Gotte...", trans.: "...Krodo, the God of the Slavs, the great God...".

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, p. 116.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 72 73 74 75 76 77 78 79 80 81 82 83 84 85 86 87 88 89 90 91 92 93 94 95 96 97 98 99 100 101 102 103 104 105 106 107 108 109 110 111 112 113 114 115 116 117 118 119 120 121 122 123 124 125 126 127 128 129 130 131 132 133 134 135 136 137 138 139 140 141 142 143 144 145 146 147 148 149 150 151 152 153 154 155 156 157 158 159 160 161 162 163 164 165 166 167 168 169 170 171 172 173 174 175 176 177 178 179 180 181 182 183 184 185 186 187 188 189 190 191 192 193 194 195 196 197 198 199 200 201 202 203 204 205 206 207 208 209 210 211 212 Mathieu-Colas 2017.

- ↑ Ivanits 1989, pp. 14–17.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, pp. 14–15.

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, pp. 115–116.

- ↑ Pietzsch, Edward, ed. (1935). Museum für sächsische vaterlandskunde. 1–5. p. 66.

- 1 2 3 Ivanits 1989, p. 17.

- ↑ Stanisław Jakubowski (1923). Prasłowiańskie motywy architektoniczne. Dębniki, Kraków: Orbis. Illustrations of Jakubowski's artworks.

- 1 2 3 Creuzer & Mone 1822, p. 197.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Ingemann 1824.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Heck 1852, p. 291.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Leeming 2005, p. 360.

- ↑ Creuzer & Mone 1822, pp. 195–197; Heck 1852, pp. 289–290.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, p. 8; Máchal 1918, p. 249.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hanuš 1842, p. 135.

- 1 2 Marjanić 2003, pp. 193, 197–199.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Máchal 1918, p. 250.

- ↑ Mathieu-Colas 2017; Rudy 1985, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Máchal 1918, p. 249.

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, pp. 135, 280.

- 1 2 3 Marjanić 2003, p. 181.

- 1 2 3 4 Marjanić 2003, p. 193.

- ↑ Marjanić 2003, p. 186.

- 1 2 Marjanić 2003, pp. 181, 189–190.

- 1 2 3 Marjanić 2003, p. 194.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hanuš 1842, p. 279.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, p. 355, note 44.

- ↑ Marjanić 2003, p. 182.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, pp. 287 ff.

- ↑ Trkanjec 2013, p. 17.

- 1 2 Dynda 2014, p. 59.

- ↑ Dynda 2014, p. 64.

- ↑ Dynda 2014, p. 63.

- ↑ Dynda 2014, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 Rudy 1985, pp. 27–29.

- 1 2 3 Rudy 1985, pp. 7–8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Leeming 2005, p. 359.

- 1 2 3 4 Hanuš 1842, p. 160.

- ↑ Ingemann 1824; Hanuš 1842, pp. 160–161.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rudy 1985, p. 17.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, p. 19.

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, p. 99.

- 1 2 Rudy 1985, p. 6.

- 1 2 3 Marjanić 2003, p. 190.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, pp. 17–21.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, pp. 219 ff.

- 1 2 3 Heck 1852, p. 290.

- 1 2 Mathieu-Colas 2017; Hanuš 1842, p. 171.

- ↑ Leeming 2005, p. 359; Hanuš 1842, p. 171.

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, pp. 171, 180.

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, p. 171.

- ↑ Mathieu-Colas 2017; Rudy 1985, p. 18.

- ↑ Leeming 2005, pp. 359–360.

- ↑ Dynda 2014, p. 62.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, p. 286.

- 1 2 3 Rudy 1985, p. 7.

- ↑ Khmara, Anatoly Vladimirovich (2008). Образование: гуманитарные дисциплины, творчество и созидание [Education: Humanities, Creativity and Creation]. Образование через всю жизнь: непрерывное образование в интересах устойчивого развития (Education Throughout Life: Continuing Education for Sustainable Development). p. 68.

- 1 2 3 Rudy 1985, p. 29.

- ↑ Borissoff 2014, p. 9, note 1.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, pp. 296 ff.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, p. 8; Szyjewski 2003, pp. 108–109.

- ↑ Grzegorzewic, Ziemisław (2016). O Bogach i ludziach. Praktyka i teoria Rodzimowierstwa Słowiańskiego [About the Gods and people. Practice and theory of Slavic Heathenism] (in Polish). Olsztyn: Stowarzyszenie "Kołomir". p. 78. ISBN 9788394018085.

- ↑ Borissoff 2014, p. 23, 29.

- ↑ Borissoff 2014, pp. 11–12.

- ↑ Robbins Dexter, Miriam Robbins (1984). "Proto-Indo-European Sun Maidens and Gods of the Moon". Mankind Quarterly. 25 (1–2). pp. 137–144.

- 1 2 Rudy 1985, p. 30.

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, pp. 177–180.

- 1 2 Hanuš 1842, p. 177.

- 1 2 3 Hanuš 1842, p. 180.

- ↑ Buttmann, Alexander (1856). Die deutschen Ortsnamen: mit besonderer Berücksichtigung der ursprünglich wendischen in der Mittelmark und Niederlausitz. F. Dümmler. p. 168.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hanuš 1842, p. 280.

- 1 2 Wagener 1842, p. 626.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, p. 22; Hanuš 1842, p. 279.

- 1 2 3 Mathieu-Colas 2017; Leeming 2005, p. 360.

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, pp. 279–281.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Rudy 1985, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 Rudy 1985, p. 24.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, p. 23.

- ↑ Ivanov, Vyacheslav; Toporov, Vladimir (1994). "Славянская мифология" [Slavic mythology]. Российская энциклопедия (Russian Encyclopedia).

- 1 2 Rudy 1985, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, pp. 21–22.

- ↑ Mathieu-Colas 2017; Gasparini 2013.

- 1 2 Ivanits 1989, p. 14.

- ↑ Marjanić 2003, pp. 190–191.

- ↑ Leeming 2005, p. 360; Marjanić 2003, p. 191, note 20.

- ↑ Ingemann 1824; Heck 1852, p. 291.

- ↑ Kanngiesser 1824, p. 202.

- ↑ Mathieu-Colas 2017; Kanngiesser 1824, p. 202.

- ↑ Dixon-Kennedy 1998, p. 156.

- 1 2 Zhuravylov 2005, p. 239.

- 1 2 Zhuravylov 2005, p. 240.

- ↑ Marjanić 2003, p. 193, note 27.

- 1 2 Rudy 1985, p. 25.

- ↑ Boryna, Maciej (2004). Boski Flins na Dolnym Śla̜sku, Łużycach i w Saksonii [Divine Flins in Lower Silesia, Lusatia and Saxony]. Szprotawa: Zielona Góra Eurodruk.

- ↑ Kanngiesser 1824, p. 205.

- ↑ Hubbs 1993, p. 64.

- 1 2 3 4 Borissoff 2014, p. 25.

- 1 2 Hanuš 1842, p. 275.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Hanuš 1842, pp. 218–219.

- ↑ Mathieu-Colas 2017; Hanuš 1842, pp. 98–99.

- ↑ Leeming 2005, p. 359; Rudy 1985, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 Hanuš 1842, pp. 216–218.

- 1 2 Rudy 1985, p. 18.

- ↑ Mathieu-Colas 2017; Rudy 1985, p. 30.

- 1 2 3 Hanuš 1842, pp. 368–369.

- 1 2 Rudy 1985, pp. 34–35.

- ↑ Ivanits 1989, pp. 13, 17.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, pp. 42–45.

- 1 2 Hanuš 1842, p. 172.

- ↑ Mathieu-Colas 2017; Hanuš 1842, p. 180.

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, p. 176.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, pp. 7, 18.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, p. 251.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, pp. 251–252.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, p. 252.

- ↑ Husain 2003, p. 170.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, pp. 227–228.

- ↑ The hypothesis that Berehynia is a major goddess is argued by Halyna Lozko, leader of the Federation of Ukrainian Rodnovers. Cf. Lozko, Halyna (17 October 2002). "Берегиня: Богиня чи Русалка?" [Bereginia: Goddess or rusalka?]. golosiyiv.kiev.ua. Archived from the original on 20 July 2011.

- ↑ Ivanits 1989, p. 78.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, pp. 20–21.

- ↑ Rudy 1985, p. 21.

- 1 2 Máchal 1918, p. 270.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, pp. 270–271.

- 1 2 3 Máchal 1918, p. 253.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, p. 254.

- 1 2 Máchal 1918, p. 256.

- 1 2 Arnaudov 1968.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, p. 259.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, pp. 253–255.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, pp. 256–259.

- 1 2 3 Dal 1863, p. 2652.

- 1 2 3 Máchal 1918, p. 261.

- 1 2 3 Hanuš 1842, pp. 172–173.

- 1 2 Cherepanova 1983, p. 30.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, p. 262.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, p. 269.

- 1 2 3 Máchal 1918, p. 267.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Máchal 1918, p. 244.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, p. 240.

- 1 2 3 Máchal 1918, p. 245.

- 1 2 3 4 Máchal 1918, p. 246.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, p. 241.

- ↑ Ivanits 1989, p. 61.

- ↑ Máchal 1918, pp. 240–241.

- ↑ Ivanits 1989, p. 58.

- ↑ Dynda 2014, p. 61.

- ↑ Marjanić 2003, p. 192.

- ↑ Ingemann 1824; Hanuš 1842, p. 381.

- 1 2 Hanuš 1842, p. 381.

- ↑ Hanuš 1842, p. 182.

Sources

- Cherepanova, Olga Aleksandrovna (1983). Мифологическая лексика русского Севера [Mythological vocabulary of the Russian North] (in Russian). Leningrad University.

- Dal, Vladmir Ivanovich (1863). Толковый словарь живого великорусского языка [Explanatory Dictionary of the Living Great Russian Language] (in Russian). Consulted 2014 edition by Directmedia.

- Creuzer, Georg Friedrich; Mone, Franz Joseph (1822). Geschichte des Heidentums im nördlichen Europa. Symbolik und Mythologie der alten Völker (in German). 1. Georg Olms Verlag. ISBN 9783487402741.

- Borissoff, Constantine L. (2014). "Non-Iranian origin of the Eastern-Slavonic god Xŭrsŭ/Xors" (PDF). Studia mythologica Slavica. 17. Institute of Slovenian Ethnology. pp. 9–36. ISSN 1408-6271. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 February 2018.

- Dixon-Kennedy, Mike (1998). Encyclopedia of Russian and Slavic Myth and Legend. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576070635.

- Dynda, Jiří (2014). "The Three-Headed One at the Crossroad: A Comparative Study of the Slavic God Triglav" (PDF). Studia mythologica Slavica. 17. Institute of Slovenian Ethnology. pp. 57–82. ISSN 1408-6271. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 July 2017.

- Gasparini, Evel (2013). "Slavic religion". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- Hanuš, Ignác Jan (1842). Die Wissenschaft des Slawischen Mythus im weitesten, den altpreussisch-lithauischen Mythus mitumfassenden Sinne. Nach Quellen bearbeitet, sammt der Literatur der slawisch-preussisch-lithauischen Archäologie und Mythologie (in German). J. Millikowski.

- Heck, Johann Georg (1852). "The Slavono-Vendic Mythology". Iconographic Encyclopaedia of Science, Literature, and Art. 4. New York: R. Garrigue. pp. 289–293.

- Hubbs, Joanna (1993). Mother Russia: The Feminine Myth in Russian Culture. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. ISBN 9780253115782.

- Husain, Shahrukh (2003). The Goddess: Power, Sexuality, and the Feminine Divine. University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472089345.

- Ingemann, B. S. (1824). Grundtræk til En Nord-Slavisk og Vendisk Gudelære [Fundamentals of a North Slavic and Wendish mythology] (in Danish). Copenhagen.

- Ivanits, Linda J. (1989). Russian Folk Belief. M. E. Sharpe. ISBN 9780765630889.

- Ivakhiv, Adrian (2005). "The Revival of Ukrainian Native Faith". In Michael F. Strmiska (ed.). Modern Paganism in World Cultures: Comparative Perspectives. Santa Barbara: ABC-Clio. pp. 209–239. ISBN 9781851096084.

- Kanngiesser, Peter Friedrich (1824). Bekehrungsgeschichte der Pommern zum Christenthum: Die heidnische Zeit. Geschichte von Pommern bis auf das Jahr 1129 (in German). 1. Universität Greifswald.

- Leeming, David (2005). The Oxford Companion to World Mythology. Sydney: Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780190288884.

- Máchal, Jan (1918). "Slavic Mythology". In L. H. Gray. The Mythology of all Races. III, Celtic and Slavic Mythology. Boston. pp. 217–389.

- Marjanić, Suzana (2003). "The Dyadic Goddess and Duotheism in Nodilo's The Ancient Faith of the Serbs and the Croats" (PDF). Studia mythologica Slavica. 6. Institute of Slovenian Ethnology. pp. 181–204. ISSN 1408-6271. Archived from the original (PDF) on 18 September 2016.

- Mathieu-Colas, Michel (2017). "Dieux slaves et baltes" (PDF). Dictionnaire des noms des divinités. France: Archive ouverte des Sciences de l'Homme et de la Société, Centre national de la recherche scientifique. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 August 2017. Retrieved 24 May 2017.

- Robbins Dexter, Miriam Robbins (1984). "Proto-Indo-European Sun Maidens and Gods of the Moon". Mankind Quarterly. 25 (1–2). pp. 137–144.

- Rudy, Stephen (1985). Contributions to Comparative Mythology: Studies in Linguistics and Philology, 1972–1982. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 9783110855463.

- Szyjewski, Aleksander (2003). Religia Słowian [The Religion of the Slavs] (in Polish). Kraków: Wydawnictwo WAM. ISBN 9788373182059.

- Trkanjec, Luka (2013). "Chthonic aspects of the Pomeranian deity Triglav and other tricephalic characters in Slavic mythology" (PDF). Studia mythologica Slavica. 16. Institute of Slovenian Ethnology. pp. 9–25. ISSN 1408-6271. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 December 2015.

- Wagener, Samuel Christoph (1842). Handbuch der vorzüglichsten, in Deutschland entdeckten Alterthümer aus heidnischer Zeit; beschrieben und versinnlicht durch 1390 lithographirte Abblidungen (in German). Voigt.

- Zhuravylov, Anatoly Fedorovich (2005). Язык и миф. Лингвистический комментарий к труду А. Н. Афанасьева "Поэтические воззрения славян на природу" [Language and myth. Linguistic commentary on the work of A. N. Afanasyev "Poetic views of the Slavs on nature"] (PDF). Традиционная духовная культура славян (Traditional spiritual culture of the Slavs) (in Russian). Indrik, Institute for Slavic Studies of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

- Arnaudov, Mihail (1968). Отчерци по българския фолклор [Snapshots of Bulgarian Folklore] (in Bulgarian). I том 1. Sofia: Проф. Марин Дринов, 1996. ISBN 9544304622.

- Arnaudov, Mihail (1968). Отчерци по българския фолклор [Snapshots of Bulgarian Folklore] (in Bulgarian). II том 2. Sofia: Проф. Марин Дринов, 1996. ISBN 9544304630.

_Swastika_(%D0%A1%D0%B2%D0%B0%D1%81%D1%82%D0%B8%D0%BA%D0%B0)_-_Rodnovery.svg.png)