Adonis

| Adonis | |

|---|---|

| God of beauty, desire and vegetation | |

| |

| Abode | Lebanon |

| Symbol | Anemones |

| Personal information | |

| Spouse | Aphrodite |

| Children | Golgos, Beroe |

| Parents | Cinyras and Myrrha (by Ovid), Phoenix and Alphesiboea (by Hesiod) |

| Equivalents | |

| Mesopotamian equivalent | Dumuzid, Tammuz |

| Levantine/Canaanite equivalent | Tammuz, Adonis |

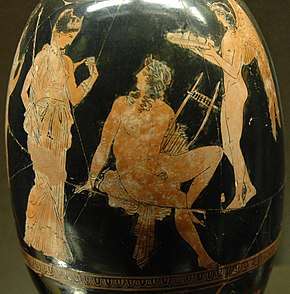

Adonis[lower-alpha 1] was the mortal lover of the goddess Aphrodite in Greek mythology. In Ovid's first-century AD telling of the myth, he was conceived after Aphrodite cursed his mother Myrrha to lust after her own father, King Cinyras of Cyprus. Myrrha had sex with her father in complete darkness for nine nights, but he discovered her identity and chased her with a sword. The gods transformed her into a myrrh tree and, in the form of a tree, she gave birth to Adonis. Aphrodite found the infant and gave him to be raised by Persephone, the queen of the Underworld. Adonis grew into an astonishingly handsome young man, causing Aphrodite and Persephone to feud over him, with Zeus eventually decreeing that Adonis would spend one third of the year in the Underworld with Persephone, one third of the year with Aphrodite, and the final third of the year with whomever he chose. Adonis chose to spend his final third of the year with Aphrodite.

One day, Adonis was gored by a wild boar during a hunting trip and died in Aphrodite's arms as she wept. His blood mingled with her tears and became the anemone flower. Aphrodite declared the Adonia festival commemorating his tragic death, which was celebrated by women every year in midsummer. During this festival, Greek women would plant "gardens of Adonis", small pots containing fast-growing plants, which they would set on top of their houses in the hot sun. The plants would sprout, but soon wither and die. Then the women would mourn the death of Adonis, tearing their clothes and beating their breasts in a public display of grief. The Greeks considered Adonis's cult to be of Oriental origin. Adonis's name comes from a Canaanite word meaning "lord" and modern scholars consider the story of Aphrodite and Adonis to be derived from the earlier Mesopotamian myth of Inanna (Ishtar) and Dumuzid (Tammuz).

In late nineteenth and early twentieth century scholarship of religion, Adonis was widely seen as a prime example of the archetypal dying-and-rising god, but the existence of the "dying-and-rising god" archetype has been largely rejected by modern scholars and its application to Adonis is undermined by the fact that no pre-Christian text ever describes Adonis as rising from the dead and the only possible references to his resurrection are late, ambiguous allusions made by Christian writers. His name is often applied in modern times to handsome youths, of whom he is the archetype.

Etymology and origin

The Greek Ἄδωνις (Greek pronunciation: [ádɔːnis]), Adōnis was a borrowing from the Canaanite word ʼadōn, meaning "lord",[1][2][3] which is related to Adonai (Hebrew: אֲדֹנָי), one of the titles used to refer to the God of the Hebrew Bible and still used in Judaism to the present day.[2] Syrian Adonis is Gaus.[4] or Aos, akin to Egyptian Osiris, the Semitic Tammuz and Baal Hadad, the Etruscan Atunis and the Phrygian Attis, all of whom are associated with vegetation.

Origin of the cult

The myth of Aphrodite and Adonis is probably derived from the ancient Sumerian legend of Inanna and Dumuzid.[6][7][8] The Greek name Ἄδωνις (Adōnis, Greek pronunciation: [ádɔːnis]) is derived from the Canaanite word ʼadōn, meaning "lord".[9][8]

The cult of Inanna and Dumuzid may have been introduced to the Kingdom of Judah during the reign of King Manasseh.[10] Ezekiel 8:14 mentions Adonis under his earlier East Semitic name Tammuz[11][12] and describes a group of women mourning Tammuz's death while sitting near the north gate of the Temple in Jerusalem.[11][12]

The earliest known Greek reference to Adonis comes from a fragment of a poem by the Lesbian poetess Sappho, dating to the seventh century BC,[13] in which a chorus of young girls asks Aphrodite what they can do to mourn Adonis's death.[13] Aphrodite replies that they must beat their breasts and tear their tunics.[13] In Greek mythology, Adonis is from Phoenicia. He was born and died at the foot of the falls in the village of Afqa, located in the Jbeil District of the Mount Lebanon Governorate, 71 kilometres (44 mi) northeast of Beirut in modern-day Lebanon. The ruins of the celebrated temple of Aphrodite Aphakitis— the Aphrodite particular to this site— are located there. The cult of Adonis has also been described as corresponding to the cult of the Phoenician god Baal.[6] As Walter Burkert explains:

Women sit by the gate weeping for Tammuz, or they offer incense to Baal on roof-tops and plant pleasant plants. These are the very features of the Adonis legend: which is celebrated on flat roof-tops on which sherds sown with quickly germinating green salading are placed, Adonis gardens... the climax is loud lamentation for the dead god.[14]

The exact date when the legend of Adonis became integrated into Greek culture is still disputed. Walter Burkert questions whether Adonis had not from the very beginning come to Greece with Aphrodite.[14] "In Greece," Burkert concludes, "the special function of the Adonis legend is as an opportunity for the unbridled expression of emotion in the strictly circumscribed life of women, in contrast to the rigid order of polis and family with the official women's festivals in honour of Demeter." Both Greek and Near Eastern scholars have questioned this connection.[14]

Parentage and birth

Adonis's birth is shrouded in confusion for those who require a single, authoritative version, for various peripheral stories circulated concerning Adonis' parentage.

The most widely accepted version is recounted in Ovid's Metamorphoses, where Adonis is the son of Myrrha and her father Cinyras. Myrrha turned into a myrrh tree and Lucina helped the tree to give birth to Adonis.[15]

The patriarchal Hellenes sought a father for the god, and found him in Byblos and Cyprus, which scholars take to indicate the direction from which Adonis had come to the Greeks. Pseudo-Apollodorus, (Bibliotheke, 3.182) considered Adonis to be the son of Cinyras, of Paphos on Cyprus, and Metharme. According to pseudo-Apollodorus' Bibliotheke, Hesiod, in an unknown work that does not survive, made of him the son of Phoenix and the otherwise unidentified Alphesiboea.[16]

In Cyprus, the cult of Adonis gradually superseded that of Cinyras.[17] Hesiod made him the son of Phoenix, eponym of the Phoenicians, thus a figure of Phoenician origin; his association with Cyprus is not attested before the classical era. W. Atallah[18] suggests that the later Hellenistic myth of Adonis represents the conflation of two independent traditions.

Alternatively the late source Bibliotheke calls him the son of Cinyras and Metharme. Another version of the myth is that Aphrodite compelled Myrrha (or Smyrna) to commit incest with her father Theias, the king of Assyria. Fleeing his wrath, Myrrha was turned into a myrrh tree. Theias struck the tree with an arrow, whereupon it burst open and Adonis emerged. Another version has a wild boar tear open the tree with its tusks, thus foreshadowing Adonis' death.

The city Berytos (Beirut) in Lebanon was named after the daughter of Adonis and Aphrodite, Beroe. Both Dionysus and Poseidon fell in love with her. She would eventually marry Poseidon.

Myth

While Sappho does not describe the myth of Adonis, later sources flesh out the details:[20] Adonis was the son of Myrrha, who was cursed by Aphrodite with insatiable lust for her own father, King Cinyras of Cyprus,[21] after Myrrha's mother bragged that her daughter was more beautiful than the goddess.[21] Driven out after becoming pregnant, Myrrha was changed into a myrrh tree, but still gave birth to Adonis.[22]

Aphrodite found the baby,[19] and took him to the underworld to be fostered by Persephone.[19] She returned for him once he was grown[19] and discovered him to be strikingly handsome.[19] Persephone wanted to keep Adonis;[19] Zeus settled the dispute by decreeing that Adonis would spend one third of the year with Aphrodite, one third with Persephone, and one third with whomever he chose.[19] Adonis chose Aphrodite, and they remained constantly together.[19]

Then, one day while Adonis was out hunting, he was wounded by a wild boar, and bled to death in Aphrodite's arms.[19] In different versions of the story, the boar was either sent by Ares, who was jealous that Aphrodite was spending so much time with Adonis,[23] by Artemis, who wanted revenge against Aphrodite for having killed her devoted follower Hippolytus,[23] or by Apollo, to punish Aphrodite for blinding his son Erymanthus.[24] The story also provides an etiology for Aphrodite's associations with certain flowers.[23] Reportedly, as she mourned Adonis's death, she caused anemones to grow wherever his blood fell,[19][23] and declared a festival on the anniversary of his death.[19] In one version of the story, Aphrodite injured herself on a thorn from a rose bush[23] and the rose, which had previously been white, was stained red by her blood.[23] According to Lucian's De Dea Syria,[25] each year during the festival of Adonis, the Adonis River in Lebanon (now known as the Abraham River) ran red with blood.[19]

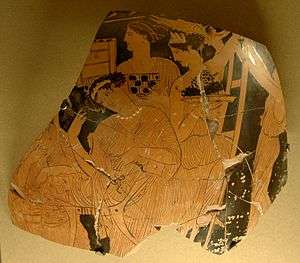

Cult

The myth of Adonis is associated with the festival of the Adonia, which was celebrated by Greek women every year in midsummer.[8][26] The festival, which was evidently already celebrated in Lesbos by Sappho's time,[8] seems to have first become popular in Athens in the mid-fifth century BC.[8] At the start of the festival, the women would plant a "garden of Adonis",[8] a small garden planted inside a small basket or a shallow piece of broken pottery containing a variety of quick-growing plants, such as lettuce and fennel, or even quick-sprouting grains such as wheat and barley.[8][27] The women would then climb ladders to the roofs of their houses,[8] where they would place the gardens out under the heat of the summer sun.[8] The plants would sprout in the sunlight,[8] but wither quickly in the heat.[28] Then the women would mourn and lament loudly over the death of Adonis,[29] tearing their clothes and beating their breasts in a public display of grief.[29] The third century BC poet Euphorion of Chalcis remarked in his Hyacinth that "Only Cocytus washed the wounds of Adonis".[30]

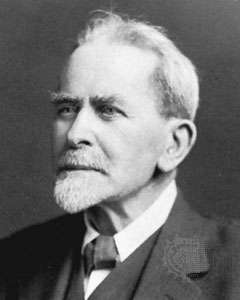

Dying-and-rising god archetype

The late nineteenth-century Scottish anthropologist Sir James George Frazer wrote extensively about Adonis in his monumental study of comparative religion The Golden Bough (the first edition of which was published in 1890)[31][34] as well as in later works.[35] Frazer claimed that Adonis was just one example of the archetype of a "dying-and-rising god" found throughout all cultures.[32][31][36] Frazer's main intention was to prove that all religions were fundamentally the same[37] and that all the essential features of Christianity could be found in earlier religions.[38] Frazer's arguments were criticized as sloppy and amateurish from the beginning,[32] but his claims became widely influential in late nineteenth and early twentieth century scholarship of religion.[32][33][31]

In the mid-twentieth century, scholars began to severely criticize the designation of "dying-and-rising god".[35][39][40] In 1987, Jonathan Z. Smith concluded in Mircea Eliade's Encyclopedia of Religion that "The category of dying and rising gods, once a major topic of scholarly investigation, must now be understood to have been largely a misnomer based on imaginative reconstructions and exceedingly late or highly ambiguous texts."[39][41] He further argued that the deities previously referred to as "dying-and-rising" would be better termed separately as "dying gods" and "disappearing gods",[39][40] asserting that before Christianity, the two categories were distinct and gods who "died" did not return, and those who returned never truly "died".[39][40] By the end of the twentieth century, most scholars had come to agree that the notion of a "dying-and-rising god" was an invention[42][33][43] and that the term was not a useful scholarly designation.[42][33][43]

The foremost problem with the application of the label "dying-and-rising god" to Adonis is the fact that he is never described as rising from the dead in any extant Graeco-Roman writings[41] and the only possible allusions to his supposed resurrection come from late, highly ambiguous statements made by Christian authors.[41][lower-alpha 2] The part of Adonis's myth in which he spends a third of the year in the Underworld with Persephone is not a death and resurrection,[41] but merely an instance of a living person staying in the Underworld.[41]

Cultural references

In relatively modern times, the myth of Adonis has featured prominently in a variety of cultural and artistic works. Giovan Battista Marino's masterpiece, Adone, published in 1623, is a long, sensual poem, which elaborates the myth of Adonis, and represents the transition in Italian literature from Mannerism to the Baroque. Shakespeare wrote the poem Venus and Adonis (Shakespeare Poem). Adonis features prominently in Book 3 of Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene. Percy Bysshe Shelley wrote the poem Adonais for John Keats, and uses the myth as an extended metaphor for Keats' death. Such allusions continue today. Adonis (an Arabic transliteration of the same name, أدونيس) is the pen name of a famous Syrian poet, Ali Ahmad Said Asbar. His choice of name relates especially to the rebirth element of the myth of Adonis (also called "Tammuz" in Arabic), which was an important theme in mid-20th century Arabic poetry, chiefly amongst followers of the "Free Verse" (الشعر الحر) movement founded by Iraqi poet Badr Shakir al-Sayyab. Adunis has used the myth of his namesake in many of his poems, for example in "Wave I", from his most recent book "Start of the Body, End of the Sea" (Saqi, 2002), which includes a complete retelling of the birth of the god.

Venus and Adonis (c. 1595) by Annibale Carracci

Venus and Adonis (c. 1595) by Annibale Carracci Venus and Cupid lamenting the dead Adonis (1656) by Cornelis Holsteyn

Venus and Cupid lamenting the dead Adonis (1656) by Cornelis Holsteyn Death of Adonis (1684-1686) by Luca Giordano.

Death of Adonis (1684-1686) by Luca Giordano. The Death of Adonis (1709) by Giuseppe Mazzuoli

The Death of Adonis (1709) by Giuseppe Mazzuoli Venus and Adonis (1792) by François Lemoyne

Venus and Adonis (1792) by François Lemoyne

See also

- Adonia, feasts celebrating Adonis

- Adonism

- Apheca

- Myrrha, mother of Adonis per Greek mythology

- Adonis belt

Psychology:

- Muscle dysmorphia, as part of Adonis Complex

- Theorizing about Myth, a Jungian interpretation of the Adonis myth by R. Segal

Notes

- ↑ /əˈdɒnɪs,

əˈdoʊnɪs/ ; Greek: Ἄδωνις - ↑ Origen discusses Adonis, (whom he associates with Tammuz), in his Selecta in Ezechielem ( “Comments on Ezekiel”), noting that "they say that for a long time certain rites of initiation are conducted: first, that they weep for him, since he has died; second, that they rejoice for him because he has risen from the dead (apo nekrôn anastanti)" (cf. J.-P. Migne, Patrologiae Cursus Completus: Series Graeca, 13:800).

References

- ↑ W. Burkert (1985), Greek Religion, pp. 176–77.

- 1 2 Botterweck, G. Johannes; Ringgren, Helmer, eds. (1974). Theological Dictionary of the Old Testament. Vol. 1 (reprint, revised ed.). Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing. pp. 59–74. ISBN 9780802823380.

- ↑ West, M. L. (1997). The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press. p. 57. ISBN 0-19-815221-3. Retrieved 30 May 2017.

- ↑ Detienne, Marcel (1994). The Gardens of Adonis: Spices in Greek Mythology, Princeton University Press, ISBN 978-0-691-00104-3 (p.137)

- ↑ Lung 2014.

- 1 2 West 1997, p. 57.

- ↑ Kerényi 1951, p. 67.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Cyrino 2010, p. 97.

- ↑ Burkert 1985, pp. 176–177.

- ↑ Pryke 2017, p. 193.

- 1 2 Pryke 2017, p. 195.

- 1 2 Warner 2016, p. 211.

- 1 2 3 West 1997, pp. 530–531.

- 1 2 3 Burkert 1985, p. 117.

- ↑ Ovid, Metamorphoses X, 298–518

- ↑ Ps.-Apollodorus, iii.14.4.1.

- ↑ Atallah 1966

- ↑ Atallah 1966.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Kerényi 1951, p. 76.

- ↑ Cyrino 2010, p. 95.

- 1 2 Kerényi 1951, p. 75.

- ↑ Kerényi 1951, pp. 75=76.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Cyrino 2010, p. 96.

- ↑ According to Nonnus, Dionysiaca 42.1f. Servius on Virgil's Eclogues x.18; Orphic Hymn lv.10; Ptolemy Hephaestionos, i.306u, all noted by Graves. Atallah (1966) fails to find any cultic or cultural connection with the boar, which he sees simply as a heroic myth-element.

- ↑ Kerényi 1951, p. 279.

- ↑ W. Atallah, Adonis dans la littérature et l'art grecs, Paris, 1966.

- ↑ Detienne 1972.

- ↑ Cyrino 2010, pp. 97–98.

- 1 2 Cyrino 2010, p. 98.

- ↑ Remarked upon in passing by Photius, Biblioteca 190 (on-line translation).

- 1 2 3 4 Ehrman 2012, pp. 222–223.

- 1 2 3 4 Barstad 1984, p. 149.

- 1 2 3 4 Eddy & Boyd 2007, pp. 142–143.

- ↑ Mettinger 2004, p. 375.

- 1 2 Barstad 1984, pp. 149–150.

- ↑ Eddy & Boyd 2007, pp. 140–142.

- ↑ Ehrman 2012, p. 222.

- ↑ Barstad 1984, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith 1987, pp. 521–527.

- 1 2 3 Mettinger 2004, p. 374.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Eddy & Boyd 2007, p. 143.

- 1 2 Ehrman 2012, p. 223.

- 1 2 Mettinger 2004, pp. 374-375.

Bibliography

- Barstad, Hans M. (1984), The Religious Polemics of Amos: Studies in the Preaching of Am 2, 7B-8; 4,1-13; 5,1-27; 6,4-7; 8,14, Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, ISBN 9789004070172

- Burkert, Walter (1985), Greek Religion, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press, ISBN 0-674-36281-0

- Cyrino, Monica S. (2010), Aphrodite, Gods and Heroes of the Ancient World, New York City, New York and London, England: Routledge, ISBN 978-0-415-77523-6

- Detienne, Marcel, 1972. Les jardins d'Adonis, translated by Janet Lloyd, 1977. The Gardens of Adonis, Harvester Press.

- Eddy, Paul Rhodes; Boyd, Gregory A. (2007), The Jesus Legend: A Case for the Historical Reliability of the Synoptic Jesus Tradition, Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, ISBN 978-0801031144

- Mettinger, Tryggve N. D. (2004), "The "Dying and Rising God": A Survey of Research from Frazer to the Present Day", in Batto, Bernard F.; Roberts, Kathryn L., David and Zion: Biblical Studies in Honor of J.J.M. Roberts, Winona Lake, Indiana: Eisenbrauns, ISBN 1-57506-092-2

- Ehrman, Bart D. (2012), Did Jesus Exist?: The Historical Argument for Jesus of Nazareth, New York City, new York: HarperCollins, ISBN 978-0-06-220644-2

- Smith, Jonathan Z. (1987), "Dying and Rising Gods", in Eliade, Mircea, The Encyclopedia of Religion, IV, London, England: Macmillan, pp. 521–527, ISBN 0029097002

- Kerényi, Karl (1951), The Gods of the Greeks, London, England: Thames and Hudson, ISBN 0-500-27048-1

- Lung, Tang (2014), "Marriage of Inanna and Dumuzi", Ancient History Encyclopedia, Ancient History Encyclopedia

- Mahony, Patrick J. An Analysis of Shelley's Craftsmanship in Adonais. Rice University, 1964.

- O'Brian, Patrick. "Post Captain." Aubrey/Maturin series. W.W. Norton, pg. 198. 1994.

- Thiollet, Jean-Pierre, 2005. Je m'appelle Byblos, H & D, p. 71-80.

- Pryke, Louise M. (2017), Ishtar, New York and London: Routledge, ISBN 978-1-138--86073-5

- West, M. L. (1997), The East Face of Helicon: West Asiatic Elements in Greek Poetry and Myth, Oxford, England: Clarendon Press, p. 57, ISBN 0-19-815221-3