Vatnajökull

| Vatnajökull Glacier | |

|---|---|

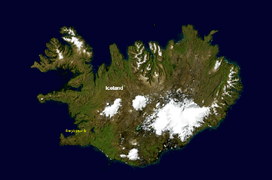

Vatnajökull, Iceland | |

| Type | Ice cap |

| Location | Iceland |

| Coordinates | 64°24′N 16°48′W / 64.400°N 16.800°WCoordinates: 64°24′N 16°48′W / 64.400°N 16.800°W |

| Area | 8,100 km2 (3,100 sq mi) |

| Thickness | 400 m (1,300 ft) average |

| Terminus | Outlet glaciers |

| Status | Retreating |

Vatnajökull (Icelandic pronunciation: [ˈvaʰtnaˌjœːkʏtl̥]), also known as the Water Glacier in English, is the largest and most voluminous ice cap in Iceland, and one of the largest in area in Europe. It is the second largest glacier in area after Austfonna on Svalbard in Norway but, nevertheless, larger by volume. It is located in the south-east of the island, covering more than 9% of the country.[1]

Name

The name Vatnajökull is derived from vatna, the genitive plural form of vatn which means "water" in Icelandic but is also used to refer to a lake, and jökull, the Icelandic for glacier.

Size

With an area of 8,100 km², Vatnajökull is the largest ice cap in Europe by volume (3,100 km³) and the second-largest (after Austfonna on Nordaustlandet, Svalbard, Norway) in area (not counting the still larger Severny Island ice cap of Novaya Zemlya, Russia, which may be regarded as located in the extreme northeast of Europe). On 7 June 2008, it became a part of the Vatnajökull National Park.[2]

The average thickness of the ice is 400 m (1,300 ft), with a maximum thickness of 1,000 m (3,300 ft). Iceland's highest peak, Hvannadalshnúkur (2,109.6 m (6,921 ft)), is located in the southern periphery of Vatnajökull, near Skaftafell National Park.

Volcanoes

Under the ice cap, as under many of the glaciers of Iceland, there are several volcanoes. Eruptions from these volcanoes have led to the development of large pockets of water beneath the ice, which may burst the weakened ice and cause a jökulhlaup (glacial lake outburst flood). During the last ice age, numerous volcanic eruptions occurred under Vatnajökull, creating many subglacial eruptions.[3]

In more modern times, the volcanoes continue to erupt beneath the glaciers, resulting in many documented floods. One jökulhlaup in 1934 caused the release of 15 km3 (3.6 cu mi) of water over the course of several days.[3] The volcanic lake Grímsvötn was the source of a large jökulhlaup in 1996. There was also a considerable but short-lived eruption of the volcano under these lakes at the beginning of November 2004. In May 21, 2011 a volcanic eruption started in Grímsvötn in Vatnajökull National Park at around 7 p.m. The plume reached as high as 20 kilometres (12 mi).

Sight line

According to Guinness World Records (GWR), Vatnajökull is supposedly the object of the world's longest sight line, 550 km (340 mi) from Slættaratindur, the highest mountain in the Faroe Islands. GWR claims that "owing to the light bending effects of atmospheric refraction, Vatnajökull (2,109.6 m), Iceland, can sometimes be seen from the Faroe Islands, 340 miles (550 km) away". This may be based on an alleged sighting by a British sailor in 1939.

In culture

In 1950, a Douglas DC-4 operated by the private airline Loftleiðir crash-landed on the Vatnajökull glacier.[4]

The glacier was used as the setting for the opening sequence (set in Siberia) of the 1985 James Bond film A View to a Kill, in which Bond (played for the last time by Roger Moore) eliminated a host of armed villains before escaping in a submarine to Alaska.[5] Several other films, including another in the Bond franchise, have been filmed on or using Jökulsárlón, the terminal lake of the Breiðamerkurjökull outlet from Vatnajökull.

Westlife's official music video for their twenty-fifth single top 10 and #2 UK hit in 2009 "What About Now" is marked as the last film of the actual scenes on Vatnajökull Glacier was seen because of the distortion happened in the recent volcanic eruption.[6][7]

In November 2011, the glacier was used as a shooting location for the second season of the HBO fantasy TV series Game of Thrones.[8]

Outlet glaciers

Vatnajökull has around 30 outlet glaciers flowing from the ice cap. The Icelandic term for glacier is "jökull", and so is the term for outlet glacier. Given below is a list of outlet glaciers flowing from Vatnajökull, sorted by the four administrative territories of Vatnajökull National Park.[9] This is not a complete list.

Southern territory

- Breiðamerkurjökull

- Brókarjökull

- Falljökull

- Fjallsjökull

- Fláajökull

- Heinabergsjökull

- Hoffellsjökull

- Hólárjökull

- Hrútárjökull

- Kvíárjökull

- Lambatungnajökull

- Morsárjökull

- Skaftafellsjökull

- Skálafellsjökull

- Skeiðarárjökull

- Stigárjökull

- Svínafellsjökull

- Viðborðsjökull

- Virkisjökull

Eastern territory

- Brúarjökull

- Eyjabakkajökull

- Kverkjökull

Northern territory

Western territory

- Köldukvíslarjökull

- Síðujökull

- Skaftárjökull

- Sylgjujökull

- Tungnaárjökul

See also

References

- ↑ Guide to Iceland. "Vatnajökull". https://guidetoiceland.is/travel-iceland/drive/vatnajokull. External link in

|website=(help); Missing or empty|url=(help);|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ "Vatnajokull National Park". Háskóli Íslands. hi.is. Archived from the original on 24 April 2009. Retrieved 9 July 2010.

- 1 2 Scheffel, Richard L.; Wernet, Susan J., eds. (1980). Natural Wonders of the World. United States of America: Reader's Digest Association, Inc. pp. 394–395. ISBN 0-89577-087-3.

- ↑ "COLLISIONS AND BOMBS!". dc3history.org. 2010-04-12. Archived from the original on 2010-04-28. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑

- ↑ "Official News (GB) - New Westlife Blog : Mark". Westlife. 2010-04-16. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ Video on YouTube

- ↑ "Iceland filming location revealed". winter-is-coming.net. 28 October 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2011.

- ↑ "General information map". Vatnajökull National Park. Archived from the original on 10 June 2015. Retrieved 25 October 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Vatnajökull. |