Lawful permanent residents (United States)

Lawful permanent residents, also known as legal permanent residents, and informally known as green card holders, are a special class of immigrants under the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA),[1][2][3] with rights, benefits, and privileges to reside in the United States permanently or until they are deported (removed) from the country pursuant to applicable provisions of the INA.[4] There are an estimated 13.2 million lawful permanent residents of whom 8.9 million are eligible for citizenship of the United States.[5][6] Approximately 65,000 of them serve in the U.S. armed forces.[7]

Lawful permanent residents are entitled to U.S. citizenship after showing by a preponderance of the evidence that they, inter alia, have continuously resided in the United States for at least five years and are persons of good moral character.[8][9] Those who are under the age of 18 years automatically derive U.S. nationality and/or citizenship through at least one of their American parents.[10] Like "nationals but not citizens of the United States," the immigrants who were originally "admitted to the United States" as refugees are statutorily exempt from deportation for lifetime.[3][11][12][13][14][15][16][17]

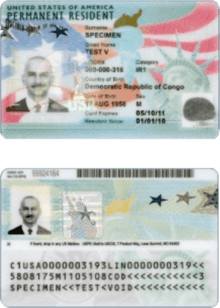

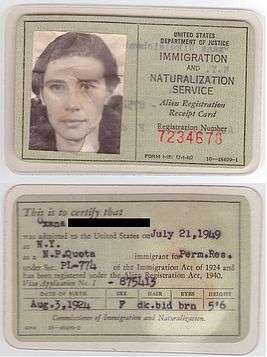

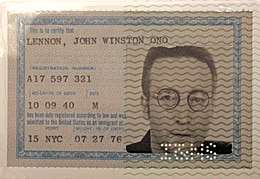

Every lawful permanent resident (LPR) is issued by the U.S. government a "permanent resident card," which is commonly known as a "green card" because of its historical greenish color.[18][19] It was formerly called "alien registration card" or "alien registration receipt card."[20] The permanent resident card serves as proof that its holder is a legal immigrant, with constitutional rights to work and reside in the United States similar to that of all other Americans.[12][13][17][14][15] It may be used to obtain a State ID card and/or a driver's license. Absent exceptional circumstances, immigrants who are 18 years of age or older could spend up to 30 days in jail for not carrying their green cards.[21][20]

Applications for permanent resident cards are decided by the United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS), but in some cases an immigration judge or a member of the Board of Immigration Appeals (BIA), acting on behalf of the U.S. Attorney General, may grant permanent residency in the course of removal proceedings. A federal judge may also do the same in particular case.[22][23]

Comparison of lawful permanent residents to nationals and citizens of the United States

The INA, which was enacted by the U.S. Congress in 1952, states that "[t]he term 'alien' means any person not a citizen or national of the United States."[24] An "immigrant" can either be an "alien" or a "national of the United States," which requires a case-by-case analysis and depends mainly on the number of continuous years he or she has spent in the United States as an LPR (green card holder).[9][1][25]

In Landon v. Plasencia, 459 U.S. 21, 32 (1982), the U.S. Supreme Court reminded the U.S. Attorney General that "once an alien gains admission to our country and begins to develop the ties that go with permanent residence, his constitutional status changes accordingly." That opinion was issued after Congress and the Reagan administration brought into the United States large number of refugee families from countries experiencing wars and genocides, such as Afghanistan, Cambodia, El Salvadore, Liberia, Palestine, Vietnam, etc.[26][3][25][27][28][11] As legal immigrants,[17] these refugee families lost their former nationalities and gradually became nationals and citizens of the United States (i.e., Americans).[24][8]

Expansion of the definition of "nationals but not citizens of the United States"

In 1986, less than a year before the United Nations Convention against Torture (CAT) became effective, Congress expressly and intentionally expanded the definition of "national of the United States" by adding paragraph (4) to 8 U.S.C. § 1408, which reads as follows:

Unless otherwise provided in section 1401 of this title, the following shall be nationals, but not citizens, of the United States at birth: .... (4) A person born outside the United States and its outlying possessions of parents one of whom is an alien, and the other a national, but not a citizen, of the United States who, prior to the birth of such person, was physically present in the United States or its outlying possessions for a period or periods totaling not less than seven years in any continuous period of ten years—(A) during which the national parent was not outside the United States or its outlying possessions for a continuous period of more than one year, and (B) at least five years of which were after attaining the age of fourteen years. (emphasis added).[29][30]

The natural reading of § 1408(4) demonstrates that it was not exclusively written for the 55,000 American Samoans but for all people who statutorily and manifestly qualify as nationals but not citizens of the United States.[30] An LPR who was admitted to the United States as a refugee, especially if he or she was a child under the age of 18, has identical rights as a national but a citizen of the United States.[26][9][12][13][14][15] Such a person can proudly say to everyone that he or she "is not an alien at all but is actually a national of the United States."[31][32] "Deprivation of [nationality]—particularly American [nationality], which is one of the most valuable rights in the world today—has grave practical consequences."[16] Congress has long warned every government employee by stating the following:

Whoever, under color of any law, statute, ordinance, regulation, or custom, willfully subjects any person in any State, Territory, or District to the deprivation of any rights, privileges, or immunities secured or protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States, or to different punishments, pains, or penalties, on account of such person being an alien, or by reason of his color, or race, than are prescribed for the punishment of citizens, shall be subject to specified criminal penalties.[33][30]

In February 1995, U.S. President Bill Clinton issued a directive in which he stated the following:

Our efforts to combat illegal immigration must not violate the privacy and civil rights of legal immigrants and U.S. citizens. Therefore, I direct the Attorney General, the Secretary of Health and Human Services, the Chair of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, and other relevant Administration officials to vigorously protect our citizens and legal immigrants from immigration-related instances of discrimination and harassment. All illegal immigration enforcement measures shall be taken with due regard for the basic human rights of individuals and in accordance with our obligations under applicable international agreements. (emphasis added).[17][30]

Today, there are approximately 13.2 million legal immigrants of whom 8.9 million are "eligible to naturalize."[5][6] An LPR can secure many types of federal jobs just like a citizen can. For example, about 65,000 members of the U.S. armed forces are LPRs.[7]

An LPR can lose the right to become a U.S. citizen and can even get deported from the country upon getting convicted of an aggravated felony, which is generally recognized as a particularly serious crime. A conviction for some lessor offenses may also trigger deportation for LPRs,[4] except those that were admitted to the United States as refugees.[3][26][11] These specific immigrants have already experienced genocide or persecution in the past, and they have no country of permanent residence other than the United States. Deporting them from the United States amounts to a very serious international crime.[12][13][14][15][16][17]

LPRs are also subject to similar obligations as U.S. citizens. Male LPRs between the ages of 18 and 25 are subject to registering in the Selective Service System. LPRs living in the United States must pay taxes on their worldwide income (this includes filing annual U.S. income tax returns), like U.S. citizens. LPRs are not allowed to vote and they cannot be elected to federal or state offices.

Like U.S. citizens, LPRs can petition (sponsor) certain family members to immigrate to the United States, but the number of family members of LPRs who can immigrate is limited by an annual cap, and there is a years-long backlog.[34][35][36]

An LPR can file Form N-400 ("application for naturalization") after five years of continuous residency in the United States.[37] This period may be shortened to three years if married to a U.S. citizen.[38] An LPR may submit his or her applications for naturalization as early as 90 days before meeting the residency requirement. In addition to continuous residency, the applicants must demonstrate good moral character, pass an English test and a civics test, and demonstrate attachment to the U.S. Constitution. In the summer of 2018, a new program was initiated to help LPRs prepare themselves for naturalization.[39]

Types of immigration

The INA stipulates that a person may obtain permanent resident status primarily through the course of the following proceedings:[40]

- immigration through a family member

- immigration through employment

- immigration through investment (from 0.5 to 1 million US dollars)

- immigration through the Diversity Lottery

- immigration through refugee or asylum status

- immigration through "The Registry" provisions of the Immigration and Nationality Act

- immigration approved by the Director of Central Intelligence.

Immigration eligibility and quotas

| Category | Eligibility | Annual quotac | Immigrant visa backlog |

|---|---|---|---|

| Family-sponsored | |||

| IR | Immediate relative (spouse, children under 21 years of age, and parents) of U.S. citizens (A U.S. citizen must be at least 21 years of age in order to sponsor his or her parents.) | No numerical limita | |

| F1 | Unmarried sons and daughters (21 years of age or older) of U.S. citizens | 23,400 | 8–21 yearsb[41] |

| F2A | Spouse and minor children (under 21 year old) of lawful permanent residents | 87,934 | 1–2 yearsb[41] |

| F2B | Unmarried sons and daughters (21 years of age or older) of permanent residents | ??? | ??? |

| F3 | Married sons and daughters of U.S. citizens | 23,400 | 10–22 yearsb[41] |

| F4 | Brothers and sisters of U.S. citizens | 65,000 | 13–24 yearsb[41] |

| Employment-basedc | |||

| EB-1 | Priority workers. There are three sub-groups: 1. Foreign nationals with extraordinary ability in sciences, arts, education, business, or athletics; 2. Foreign nationals that are outstanding professors or researchers with at least three years' experience in teaching or research and who are recognized internationally; 3. Foreign nationals that are managers and executives subject to international transfer to the United States. | 41,455[42] | currently available |

| EB-2 | Professionals holding advanced degrees (Ph.D., master's degree, or at least five years of progressive post-baccalaureate experience) or persons of exceptional ability in sciences, arts, or business | 41,455[42] | 6 months – 9 yearsb |

| EB-3 | Skilled workers, professionals, and other workers | 41,455[42] | 6 months – 10 yearsb[43] |

| EB-4 | Certain special immigrants: ministers, religious workers, current or former U.S. government workers, etc. | 10,291[42] | currently available |

| EB-5 | Investors, for investing either $500,000 in rural projects creating over 10 American jobs or $1 million in other developments[44] | 10,291[42] | currently available |

| Diversity immigrant (DV) | 50,000 | ||

| Political asylum[45] | No numerical limit | ||

| Refugee[45] | 70,000[46] | ||

| a 300,000–500,000 immediate relatives admitted annually. b No more than 7 percent of the visas may be issued to natives of any one country. Currently, individuals from China (mainland), India, Mexico and the Philippines are subject to per-country quotas in most of the categories, and the waiting time may take longer (additional 5–20 years).[47] c Spouse and minor children of the IR/F4/EB applicants, DV winners, asylums & refugees may apply for immigrant visa adjudication with their spouse or parent. The quotas include not only the principal applicants but also their nuclear family members. | |||

Application process

Applications for permanent resident cards (green cards) were decided by the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) until 2003 when the INS was abolished and replaced by the current Department of Homeland Security (DHS).[48] The whole process may take several years, depending on the type of immigrant category and the country of chargeability. An immigrant usually has to go through a three-step process to get permanent residency:

- Immigrant petition (Form I-140 or Form I-130) – in the first step, USCIS approves the immigrant petition by a qualifying relative, an employer, or in rare cases, such as with an investor visa, the applicant himself. If a sibling is applying, she or he must have the same parents as the applicant.

- Immigrant visa availability – in the second step, unless the applicant is an "immediate relative", an immigrant visa number through the National Visa Center (NVC)[49] of the United States Department of State (DOS) must be available. A visa number might not be immediately available even if the USCIS approves the petition, because the number of immigrant visa numbers is limited every year by quotas set in the Immigration and Nationality Act (INA). There are also certain additional limitations by country of chargeability. Thus, most immigrants will be placed on lengthy waiting lists. Those immigrants who are immediate relatives of a U.S. citizen (spouses and children under 21 years of age, and parents of a U.S. citizen who is 21 years of age or older) are not subject to these quotas and may proceed to the next step immediately (since they qualify for the IR immigrant category).

- Immigrant visa adjudication – in the third step, when an immigrant visa number becomes available, the applicant must either apply with USCIS to adjust their current status to permanent resident status or apply with the DOS for an immigrant visa at the nearest U.S. consulate before being allowed to come to the United States.

- Adjustment of status (AOS) – Adjustment of status is for when the immigrant is in the United States and entered the U.S. legally. Except for immediate relatives of U.S. citizens, the immigrant must also be in legal status at the time of applying for adjustment of status. For immediate relatives and other relative categories whose visa numbers are current, adjustment of status can be filed for at the same time with the petition (step 1 above). Adjustment of status is submitted to USCIS via form I-485, Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status.[50] The USCIS conducts a series of background checks (including fingerprinting for FBI criminal background check and name checks) and makes a decision on the application. Once the adjustment of status application is accepted, the alien is allowed to stay in the United States even if the original period of authorized stay on the Form I-94 is expired, but he/she is generally not allowed to leave the country until the application is approved, or the application will be abandoned. If the alien has to leave the United States during this time, he/she can apply for travel documents at the USCIS with form I-131, also called Advance parole.[51] If there is a potential risk that the applicant's work permit (visa) will expire or become invalid (laid off by the employer and visa sponsor) or the applicant wants to start working in the United States, while he/she is waiting for the decision about his/her application to change status, he/she can file form I-765, to get Employment Authorization Documents (also called EAD) and be able to continue or start working legally in the United States.[52][53] In some cases, the applicant will be interviewed at a USCIS office, especially if it is a marriage-based adjustment from a K-1 visa, in which case both spouses (the US citizen and the applicant) will be interviewed by the USCIS. If the application is approved, the alien becomes an LPR, and the actual green card is mailed to the alien's last known mailing address.

- Consular processing – This is the process if the immigrant is outside the United States, or is ineligible for AOS. It still requires the immigrant visa petition to be first completed and approved. The applicant may make an appointment at the U.S. embassy or consulate in his/her home country, where a consular officer adjudicates the case. If the case is approved, an immigrant visa is issued by the U.S. embassy or consulate. The visa entitles the holder to travel to the United States as an immigrant. At the port of entry, the immigrant visa holder immediately becomes a permanent resident, and is processed for a permanent resident card and receives an I-551 stamp in his/her passport. The permanent resident card is mailed to his/her U.S. address within several weeks.

An applicant (alien) in the United States can obtain two permits while the case is pending after a certain stage is passed in green card processing (filing of I-485).

- The first is a temporary work permit known as the Employment Authorization Document (EAD), which allows the alien to take employment in the United States.

- The second is a temporary travel document, advance parole, which allows the alien to re-enter the United States. Both permits confer benefits that are independent of any existing status granted to the alien. For example, the alien might already have permission to work in the United States under an H-1B visa.

Application process for family-sponsored visa for both parents and for children

U.S. citizens may sponsor for permanent residence in the United States the following relatives:

- Spouses, and unmarried children under the age of 21;

- Parents (once the U.S. citizen is at least 21 years old);

- Unmarried children over the age of 21 (called "sons and daughters");

- Married sons and daughters;

- Brothers and sisters (once the U.S. citizen is at least 21 years old).

U.S. permanent residents may sponsor for permanent residence in the United States the following relatives:

- Spouses, and unmarried children under the age of 21;

- Unmarried children over the age of 21 (called "sons and daughters");

The Department of State's "Visa Bulletin," issued every month, gives the priority date for those petition beneficiaries currently entitled to apply for immigrant status through immigrant visas or adjustment of status.[54] There is no annual quota for the spouses, unmarried children, and parents of U.S. citizens, so there is no waiting period for these applicants—just the required processing time. However, all other family-based categories have significant backlogs, even with a U.S. citizen petitioner.

Regardless of whether the family member being sponsored is located in the United States (and therefore likely to be applying for adjustment of status) or outside the United States (in which case the immigrant visa is the likely option), the process begins with the filing of an I-130 Petition for Alien Relative. The form and instructions can be found on the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website.[55] Required later in the process will be additional biographic data regarding the beneficiary (the person being sponsored) and a medical examination. Additional documents, such as police certificates, may be required depending on whether immigrant visa (consular processing) or adjustment of status is being utilized. In the case of consular processing outside the United States one should ensure one is up-to-date with the particular practices of the relevant US embassy or consulate.[56] All petitioners must supply the I-864 Affidavit of Support.[57]

Green-card holders and families

Green-card holders married to non-U.S. citizens are able to legally bring their spouses and minor children to join them in the USA,[58] but must wait for their priority date to become current. The foreign spouse of a green-card holder must wait for approval of an "immigrant visa" from the State Department before entering the United States. Due to numerical limitation on the number of these visas, the wait time for approval may be months or years. In the interim, the spouse cannot be legally present in the United States, unless he or she secures a visa by some other means. Green-card holders may opt to wait to become U.S. citizens, and only then sponsor their spouses and children, as the process is much faster for U.S. citizens. However, many green-card holders can choose to apply for the spouse or children and update their application after becoming a U.S. citizen.

The issue of U.S. green-card holders separated from their families for years is not a new problem. A mechanism to unite families of green-card holders was created by the LIFE Act by the introduction of a "V visa", signed into law by President Clinton. The law expired on December 31, 2000, and V visas are no longer available. From time to time, bills are introduced in Congress to reinstate V visas, but so far none have been successful.

Improving the application process in obtaining a green card

The most common challenges that USCIS faces in providing services in the green card process are: (1) the length of the application and approval process, and (2) the quotas of green cards granted. USCIS tries to shorten the time qualified applicants wait to receive permanent residence.

Challenges with processing time of application

Under the current system, immediate family members (spouse, child, and dependent mother and father), have priority status for green cards and generally wait 6 months to a year to have their green card application approved. For non-immediate family members, the process may take up to 10 years. Paperwork is processed on a first-come, first-served basis, so new applications may go untouched for several months. To address the issue of slow processing times, USCIS has made a policy allowing applicants to submit the I-130 and I-485 forms at the same time. This has reduced the processing time. Another delay in the process comes when applications have mistakes. In these cases papers are sent back to the applicant, further delaying the process. Currently the largest issue creating long wait times is not processing time, but rather immigrant visa quotas set by Congress.[59]

Quota system challenges

Long wait times are a symptom of another issue—quotas preventing immigrants from receiving immigrant visas. Georgia's Augusta Chronicle in 2006 stated that an estimated two million people are on waiting lists in anticipation to become legal and permanent residents of the United States. Immigrants need visas to get off of these waiting lists, and Congress would need to change immigration law in order to accommodate them with legal status.

The number of green cards that can be granted to family-based applicants depends on what preference category they fall under. An unlimited number of immediate relatives can receive green cards because there is no quota for that category. Family members who fall under the other various preference categories have fixed quotas, however the number of visas issued from each category may vary because unused visas from one category may rollover into another category.

Application process for employment-based visa

Many immigrants opt for this route, which typically requires an employer to "sponsor" (i.e. to petition before USCIS) the immigrant (known as the alien beneficiary) through a presumed future job (in some special categories, the applicant may apply on his/her behalf without a sponsor). The three-step process outlined above is described here in more detail for employment-based immigration applications. After the process is complete, the alien is expected to take the certified job offered by the employer to substantiate his or her immigrant status, since the application ultimately rests on the alien's employment with that company in that particular position.

- Immigrant petition – the first step includes the pre-requisite labor certification upon which the actual petition will reside.

- Labor certification – the employer must legally prove that it has a need to hire an alien for a specific position and that there is no minimally qualified U.S. citizen or LPR available to fill that position, hence the reason for hiring the alien. Some of the requirements to prove this situation include: proof of advertising for the specific position; skill requirements particular to the job; verification of the prevailing wage for a position; and the employer's ability to pay. This is currently done through an electronic system known as PERM.[60] The date when the labor certification application is filed becomes the applicant's priority date. In some cases, for highly skilled foreign nationals (EB1 and EB2 National Interest Waiver, e.g. researchers, athletes, artists or business executives) and "Schedule A" labor[61] (nurses and physical therapists), this step is waived. This step is processed by the United States Department of Labor (DOL). The labor certification is valid for 6 months from the time it is approved.

- Immigrant petition – the employer applies on the alien's behalf to obtain a visa number. The application is form I-140, Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker,[62] and it is processed by the USCIS. There are several EB (employment-based) immigrant categories (i.e. EB1-EA, EB2-NIW, EB5)[63] under which the alien may apply, with progressively stricter requirements, but often shorter waiting times. Many of the applications are processed under the EB3 category.[64] Currently, this process takes up to 6 months. Many of the EB categories allow expedited processing of this stage, known as "premium processing".

- Immigrant visa availability. When the immigrant petition is approved by the USCIS, the petition is forwarded to the NVC for visa allocation. Currently this step centers around the priority date concept.

- Priority date – the visa becomes available when the applicant's priority date is earlier than the cutoff date announced on the DOS's Visa Bulletin[65] or when the immigrant visa category the applicant is assigned to is announced as "current". A "current" designation indicates that visa numbers are available to all applicants in the corresponding immigrant category. Petitions with priority dates earlier than the cutoff date are expected to have visas available, therefore those applicants are eligible for final adjudication. When the NVC determines that a visa number could be available for a particular immigrant petition, a visa is tentatively allocated to the applicant. The NVC will send a letter stating that the applicant may be eligible for adjustment of status, and requiring the applicant to choose either to adjust status with the USCIS directly, or apply at the U.S. consulate abroad. This waiting process determines when the applicant can expect the immigration case to be adjudicated. Due to quotas imposed on EB visa categories, there are more approved immigrant petitions than visas available under INA. High demand for visas has created a backlog of approved but unadjudicated cases. In addition, due to processing inefficiencies throughout DOS and USCIS systems, not all visas available under the quota system in a given year were allocated to applicants by the DOS. Since there is no quota carry-over to the next fiscal year, for several years visa quotas have not been fully used, thus adding to the visa backlog.[66]

- Immigrant visa adjudication. When the NVC determines that an immigrant visa is available, the case can be adjudicated. If the alien is already in the USA, that alien has a choice to finalize the green card process via adjustment of status in the USA, or via consular processing abroad. If the alien is outside of the USA he/she can only apply for an immigrant visa at the U.S. consulate. The USCIS does not allow an alien to pursue consular processing and AOS simultaneously. Prior to filing the form I-485 (Adjustment of Status) it is required that the applicant have a medical examination performed by a USCIS-approved civil surgeon. The examination includes a blood test and specific immunizations, unless the applicant provides proof that the required immunizations were already done elsewhere. The civil surgeon hands the applicant a sealed envelope containing a completed form I-693, which must be included unopened with the I-485 application.[67] (The cited reference also states that the February 25, 2010 edition of the Form I-693 reflects that an individual should no longer be tested for HIV infection.)

- Adjustment of status (AOS) – after the alien has a labor certification and has been provisionally allocated a visa number, the final step is to change his or her status to permanent residency. Adjustment of status is submitted to USCIS via form I-485, Application to Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status. If an immigrant visa number is available, the USCIS will allow "concurrent filing": it will accept forms I-140 and I-485 submitted in the same package or will accept form I-485 even before the approval of the I-140.

- Consular processing – this is an alternative to AOS, but still requires the immigrant visa petition to be completed. In the past (pre-2005), this process was somewhat faster than applying for AOS, so was sometimes used to circumvent long backlogs (of over two years in some cases). However, due to recent efficiency improvements by the USCIS, it is not clear whether applying via consular processing is faster than the regular AOS process. Consular processing is also thought to be riskier since there is no or very little recourse for appeal if the officer denies the application.

Green card lottery

Each year, around 50,000 immigrant visas are made available through the Diversity Visa (DV) program, also known as the Green Card Lottery to people who were born in countries with low rates of immigration to the United States (fewer than 50,000 immigrants in the past five years). Applicants can only qualify by country of chargeability, not by citizenship. Anyone who is selected under this lottery will be given the opportunity to apply for permanent residence. They can also file for their spouse and any unmarried children under the age of 21.

If permanent residence is granted, the winner (and his/her family, if applicable) receives an immigrant visa in their passport(s) that has to be "activated" within six months of issuance at any port of entry to the United States. If already in the U.S. adjustment of status may be pursued. The new immigrant receives a stamp on the visa as proof of lawful admittance to the United States, and the individual is now authorized to live and work permanently in the United States. Finally, the actual "green card" typically arrives by mail within a few months.

Crime: green card lottery scam

There is a growing number of fraudulent green card lottery scams, in which false agents take money from applicants by promising to submit application forms for them. Most agents are not working for the distribution service. Some claim that they can increase the chance of winning the lottery. This is not true; in fact, they may delay or not submit the application. Likewise, some claim to provide to winners free airline tickets or other benefits, such as submissions in future years or cash funds. There is no way to guarantee their claims, and there are numerous nefarious reasons for them not to fulfill their promises. Applicants are advised to use only official U.S. government websites, in which the URL ends in .gov.

Green card lottery e-mail fraud

Other fraud perpetrators will e-mail potential victims posing as State Department or other government officials with requests to wire or transfer money online as part of a "processing fee." These fraudulent e-mails are designed to steal money from unsuspecting victims. The senders often use phony e-mail addresses and logos designed to make them look more like official government correspondence. One easy way to tell that an email is a fraud is that it does not end with a ".gov". One particularly common fraud email asks potential victims to wire money via Western Union to an individual (the name varies) at the following address in the United Kingdom: 24 Grosvenor Square, London. These emails come from a variety of email addresses designed to impersonate the U.S. State Department. The USCIS blog has published information on this email scam and how to report fraudulent emails to the authorities.[68] The U.S. government has issued warnings about this type of fraud or similar business practices.[69][70][71]

Registry

The "registry" is a provision of the INA which allows an alien who has previously entered the United States illegally to obtain legal permanent residence simply on the basis of having de facto resided in the country over a very long time. To avail himself of the benefit of this provision, the alien has to prove that he has continuously resided since before the stipulated "registry date".[72] The concept of "registry" was first added to the INA in 1929, with the registry date set to June 3, 1921. Since then, the registry date has been adjusted several times, being set to July 1, 1924; June 28, 1940; and June 30, 1948. The most recent adjustment to the registry date came with the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986, when it was set to January 1, 1972.[73] A number of bills have been introduced in Congress since then to further alter the registry date, but they have not been passed.[72][73]

Conditional permanent residents

As part of immigration reform under the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA), as well as further reform enacted in the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996 (IIRIRA), eligible persons who properly apply for permanent residency based on either a recent marriage to a U.S. citizen or as an investor are granted such privilege only on a conditional basis, for two years. An exception to this rule is the case of a U.S. citizen legally sponsoring a spouse in which the marriage at the time of the adjustment of status (I-485) is more than two years old. In this case, the conditional status is waived and a 10-year "permanent resident card" is issued after the USCIS approves the case. A permanent resident under the conditional clause may receive an I-551 stamp as well as a permanent resident card. The expiration date of the conditional period is two years from the approval date. The immigrant visa category is CR (conditional resident).

When this two-year conditional period is over, the permanent residence automatically expires and the applicant is subject to deportation and removal unless, up to 90 days before the conditional residence expires, the applicant must file form I-751 Petition to Remove Conditions on Residence[74] (if conditional permanent residence was obtained through marriage) or form I-829 Petition by Entrepreneur to Remove Conditions[75] (if conditional permanent residence was obtained through investment) with USCIS to have the conditions removed. Once the application is received, permanent residence is extended in 1-year intervals until the request to remove conditions is approved or denied. For conditional permanent residence obtained through marriage, both spouses must sign the form I-751; if the spouses are divorced, it is possible to get a waiver of the other spouse's signing requirement, if it can be proved that the marriage was bona fide.

The USCIS requires that the application for the removal of conditions provide both general and specific supporting evidence that the basis on which the applicant obtained conditional permanent residence was not fraudulent. For an application based on marriage, birth certificates of children, joint financial statements, and letters from employers, friends and relatives are some types of evidence that may be accepted.[76] That is to ensure that the marriage was in good faith and not a fraudulent marriage of convenience with a sole intention of obtaining a green card. A follow-up interview with an immigration officer is sometimes required but may be waived if the submitted evidence is sufficient. Both the spouses must usually attend the interview.

The applicant receives an I-551 stamp in their foreign passport upon approval of their case. The applicant is then free from the conditional requirement once the application is approved. The applicant's new permanent resident card arrives via mail to their house several weeks to several months later and replaces the old two-year conditional residence card. The new card must be renewed after 10 years, but permanent resident status is now granted for an indefinite term if residence conditions are satisfied at all times. The USCIS may request to renew the card earlier because of security enhancements of the card or as a part of a revalidation campaign to exclude counterfeit green cards from circulation.

It is important to note that the two-year conditional residence period counts toward satisfying a residency requirement for U.S. naturalization, and other purposes. Application for the removal of conditions must be adjudicated before a separate naturalization application could be reviewed by the USCIS on its own merits.

Differences between permanent residents and conditional permanent residents

Conditional permanent residents have all of the equal "rights, privileges, responsibilities and duties which apply to all other lawful permanent residents."[77] The only difference is the requirement to satisfy the conditions (such as showing marriage status or satisfying entrepreneur requirements) before the two-year period ends.

Abandonment or loss of permanent residence status

A green-card holder may abandon permanent residence by filing form I-407, with the green card, at a U.S. Embassy.[78]

Under certain conditions, permanent residence status can be lost involuntarily.[79] This includes committing a criminal act that makes a person removable from the United States. A person might also be found to have abandoned his/her status if he or she moves to another country to live there permanently, stays outside the USA for more than 365 days (without getting a re-entry permit before leaving),[80] or does not file an income tax return on their worldwide income. Permanent resident status can also be lost if it is found that the application or grounds for obtaining permanent residence was fraudulent. The failure to renew the permanent resident card does not result in the loss of status, except in the case of conditional permanent residents as noted above. Nevertheless, it is still a good idea to renew the green card on time because it also acts as a work permit and travel permit (advance parole), but if the green card is renewed late, there is no penalty or extra fee to pay.[81]

A person who loses permanent residence status is immediately removable from the United States and must leave the country as soon as possible or face deportation and removal. In some cases the person may be banned from entering the country for three or seven years, or even permanently.

Tax costs of green card relinquishment

Due to the Heart Act[82] foreign workers who have owned a green card in eight of the last 15 years and choose to relinquish it will be subject to the expatriation tax, which taxes unrealized gains above $600,000, anywhere in the world. However this will only apply to those people who have a federal tax liability greater than $139,000 a year or have a worth of more than $2 million or have failed to certify to the IRS that they have been in compliance with U.S. federal tax obligations for the past five years.[83][84]

If the green card is not relinquished then the holder is subject to double taxation when living or working outside of the United States, whether or not within their home nation, although double taxation may be mitigated by foreign tax credits.

Reading a permanent resident card

While most of the information on the card is self-evident, the computer- and human-readable signature at the bottom is not. The format follows the machine-readable travel document TD1 format:

- First line:

- 1–2: C1 or C2. C1 = resident within the United States, C2 = permanent resident commuter (living in Canada or Mexico)

- 3–5: USA (issuing country, United States)

- 6–14: 9-digit number (A#, alien number)

- 15: check digit over digits 6–14

- 16–30: 13-character USCIS receipt number,[85] padded with "<" as a filler character[86]

- Second line:

- 1–6: birth date (in YYMMDD format)

- 7: check digit over digits 1–6

- 8: gender

- 9–14: expiration date (in YYMMDD format)

- 15: check digit over digits 9–14

- 16–29: country of birth

- 30: cumulative check digit (over digits 6–30 (upper line), 1–7, 9–15, 19–29 (lower line))

- Third line:

- surname, given name, middle name, first initial of father, first initial of mother (this line is spaced with "<<" between the surname and given name). Depending on the length of the name, the father's and mother's initials may be omitted.

A full list of category codes (i.e. IR1, E21, etc.) can be found in the Federal Register[87][88] or Foreign Affairs Manual.[89]

Since May 11, 2010, new green cards contain an RFID chip[90] and can be electronically accessed at a distance. They are shipped with a protective sleeve intended to protect the card from remote access, but it is reported to be inadequate.[91]

Visa-free travel for green-card holders

Note: This list excludes countries that allow visa-free travel with valid U.S. visas (for example, Costa Rica,[92] Dominican Republic,[93] Mexico,[94] and Panama).[95] Also note that the green card holder might already have visa-free access to many destinations by virtue of the nationality already held.

- Albania: 90 days within 180 days

- Antigua and Barbuda: 30 days

- Bahamas: 30 days[96]

- Belize: permanent residents of the USA can obtain a visa on arrival, provided prior approval is obtained from Belizean Immigration (fee USD 50). Visitors may also have to pay a repatriation fee.

- Bosnia and Herzegovina: 90 days within 180 days

- Bermuda[97]

- British Virgin Islands: 1 month[98]

- Turks and Caicos Islands: 30 days

- Canada: 6 months[99] ETA required for travel by air[100]

- Caribbean Netherlands (Netherlands Antilles, Bonaire, Aruba, Sint Maarten or Curaçao): 30 days[101]

- Costa Rica: 30 days[102]

- Cayman Islands: 30 days[103]

- Dominica: 6 months

- Dominican Republic: 30 days[104]

- Georgia: 90 days within 180 days

- Guatemala: 90 days

- Honduras: 3 months

- Jamaica: 6 months

- Mexico: 180 days[105]

- Nicaragua: 3 months

- Panama: 90 days

- Serbia: 90 days[106]

- Montenegro: 30 days

- Taiwan: 30 days max. for holders of a ROC (Taiwan) Business and Academic Travel Card, issued by Republic of China (Taiwan).

- Kosovo: 15 days[107]

See also

- Blue Card (European Union)

- Permanent residency in Canada

- Indefinite leave to remain, a British residence status equivalent to the Canada Permanent Resident Card

- Permanent residency

References

- 1 2 "Lawful Permanent Residents (LPR)". U.S. Dept. of Homeland Security (DHS). April 24, 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- 1 2 ("The term 'lawfully admitted for permanent residence' means the status of having been lawfully accorded the privilege of residing permanently in the United States as an immigrant in accordance with the immigration laws, such status not having changed.") (emphasis added).

- 1 2 3 4 See generally Matter of J-H-J-, 26 I&N Dec. 563, 564-65 (BIA 2015) (collecting court cases); accord ("The provisions of paragraphs (4), (5), and (7)(A) of section 1182(a) ... shall not be applicable to any alien seeking admission to the United States under this subsection, and the Attorney General may waive any other provision of [section 1182(a)] ... with respect to such an alien for humanitarian purposes, to assure family unity, or when it is otherwise in the public interest.") (emphasis added); ("Coordination with section 1182") (same); ("An alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence in the United States shall not be regarded as seeking an admission into the United States for purposes of the immigration laws unless the alien— ... has committed an offense identified in section 1182(a)(2) of this title, unless since such offense the alien has been granted relief under section 1182(h) or 1229b(a) ....") (emphasis added); see also Matter of Campos-Torres, 22 I&N Dec. 1289 (BIA 2000) (en banc) ("Pursuant to section 240A(d)(1) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, (Supp. II 1996), an offense must be one 'referred to in section 212(a)(2)' of the Act, (1994 & Supp. II 1996), to terminate the period of continuous residence or continuous physical presence required for cancellation of removal."); cf. ("No waiver shall be granted under this subsection in the case of an alien who has previously been admitted to the United States as an alien lawfully admitted for permanent residence if either since the date of such admission the alien has been convicted of an aggravated felony or the alien has not lawfully resided continuously in the United States for a period of not less than 7 years immediately preceding the date of initiation of proceedings to remove the alien from the United States.") (emphasis added).

- 1 2 ("The term 'removable' means—(A) in the case of an alien not admitted to the United States, that the alien is inadmissible under section 1182 of this title, or (B) in the case of an alien admitted to the United States, that the alien is deportable under section 1227 of this title."); see also Tima v. Attorney General of the U.S., ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 16-4199, p.11 (3d Cir. Sept. 6, 2018) ("Section 1227 defines '[d]eportable aliens,' a synonym for removable aliens.... So § 1227(a)(1) piggybacks on § 1182(a) by treating grounds of inadmissibility as grounds for removal as well.").

- 1 2 "Estimates of the Lawful Permanent Resident Population in the United States: January 2014" (PDF). James Lee; Bryan Baker. U.S. Dept. of Homeland Security (DHS). June 2017. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- 1 2 Mejia, Brittny (June 28, 2018). "It's not just people in the U.S. illegally — ICE is nabbing lawful permanent residents too". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2018-09-15.

- 1 2 Dowd, Alan (April 2, 2018). "What a Country: Immigrants Serve US Military Well". providencemag.com. Retrieved 2018-09-22.

- 1 2 8 U.S.C. § 1427 ("Requirements of naturalization"); see also ("For the purposes of this chapter—No person shall be regarded as, or found to be, a person of good moral character who, during the period for which good moral character is required to be established is, or was— . . . .");

- "Path to U.S. Citizenship". United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS). January 22, 2013. Retrieved 2018-09-23.

- "How to Apply for U.S. Citizenship". www.usa.gov. September 4, 2018. Retrieved 2018-09-23.

- 1 2 3 Mohammadi v. Islamic Republic of Iran, 782 F.3d 9, 15 (D.C. Cir. 2015) ("The sole such statutory provision that presently confers United States nationality upon non-citizens is 8 U.S.C. § 1408."); Matter of Navas-Acosta, 23 I&N Dec. 586, 587 (BIA 2003) ("If Congress had intended nationality to attach at some point before the naturalization process is complete, we believe it would have said so."); 8 U.S.C. § 1436 ("A person not a citizen who owes permanent allegiance to the United States, and who is otherwise qualified, may, if he becomes a resident of any State, be naturalized upon compliance with the applicable requirements of this subchapter...."); ("The term 'naturalization' means the conferring of [United States nationality] upon a person after birth, by any means whatsoever.") (emphasis added); TRW Inc. v. Andrews, 534 U.S. 19, 31 (2001) ("It is a cardinal principle of statutory construction that a statute ought, upon the whole, to be so construed that, if it can be prevented, no clause, sentence, or word shall be superfluous, void, or insignificant.") (internal quotation marks omitted); see also Saliba v. Att’y Gen., 828 F.3d 182, 189 (3d Cir. 2016) ("Significantly, an applicant for naturalization has the burden of proving 'by a preponderance of the evidence that he or she meets all of the requirements for naturalization.'"); In re Petition of Haniatakis, 376 F.2d 728 (3d Cir. 1967); In re Sotos' Petition, 221 F. Supp. 145 (W.D. Pa. 1963).

- ↑ Khalid v. Sessions, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 16‐3480, p.6 (2d Cir. Sept. 13, 2018) (case involving a U.S. citizen in removal proceedings); Jaen v. Sessions, 899 F.3d 182 (2d Cir. 2018) (same); Anderson v. Holder, 673 F.3d 1089, 1092 (9th Cir. 2012) (same); Dent v. Sessions, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 17-15662, p.10-11 (9th Cir. Aug. 17, 2018) ("An individual has third-party standing when [(1)] the party asserting the right has a close relationship with the person who possesses the right [and (2)] there is a hindrance to the possessor's ability to protect his own interests.") (quoting Sessions v. Morales-Santana, 582 U.S. ___, ___, 137 S.Ct. 1678, 1689 (2017)) (internal quotation marks omitted); Yith v. Nielsen, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 16-15858, p.5-6 (9th Cir. Feb. 7, 2018); Gonzalez-Alarcon v. Macias, 884 F.3d 1266, 1270 (10th Cir. 2018); Hammond v. Sessions, No. 16-3013, p.2-3 (2d Cir. Jan. 29, 2018) (summary order); Morales-Santana v. Lynch, 804 F.3d 520, 527 (2d Cir. 2015).

- 1 2 3 Nguyen v. Chertoff, 501 F.3d 107, 109-10 (2d Cir. 2007) (case of a Vietnamese immigrant "convicted in Massachusetts of the forcible rape of a minor child....").

- 1 2 3 4 "Deprivation Of Rights Under Color Of Law". U.S. Department of Justice. August 6, 2015. Retrieved 2018-09-17.

Section 242 of Title 18 makes it a crime for a person acting under color of any law to willfully deprive a person of a right or privilege protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States. For the purpose of Section 242, acts under 'color of law' include acts not only done by federal, state, or local officials within the their lawful authority, but also acts done beyond the bounds of that official's lawful authority, if the acts are done while the official is purporting to or pretending to act in the performance of his/her official duties. Persons acting under color of law within the meaning of this statute include police officers, prisons guards and other law enforcement officials, as well as judges, care providers in public health facilities, and others who are acting as public officials. It is not necessary that the crime be motivated by animus toward the race, color, religion, sex, handicap, familial status or national origin of the victim. The offense is punishable by a range of imprisonment up to a life term, or the death penalty, depending upon the circumstances of the crime, and the resulting injury, if any.

(emphasis added). - 1 2 3 4 18 U.S.C. §§ 241–249; United States v. Lanier, 520 U.S. 259, 264 (1997) ("Section 242 is a Reconstruction Era civil rights statute making it criminal to act (1) 'willfully' and (2) under color of law (3) to deprive a person of rights protected by the Constitution or laws of the United States."); United States v. Lanier, 123 F.3d 945 (6th Cir. 1997); Hope v. Pelzer, 536 U.S. 730, 736-37 (2002); United States v. Acosta, 470 F.3d 132, 136 (2d Cir. 2006) (holding that 18 U.S.C. §§ 241 and 242 are "crimes of violence"); see also 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981–1985; Ziglar v. Abbasi, 582 U.S. ___ (2017).

- 1 2 3 4 "Article 16". Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved 2018-07-15.

[The United States] shall undertake to prevent in any territory under its jurisdiction other acts of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment which do not amount to torture as defined in article I, when such acts are committed by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity.

(emphasis added). - 1 2 3 4 "Chapter 11 - Foreign Policy: Senate OKs Ratification of Torture Treaty" (46th ed.). CQ Press. 1990. p. 806-7. Retrieved 2018-08-08.

The three other reservations, also crafted with the help and approval of the Bush administration, did the following: Limited the definition of 'cruel, inhuman or degrading' treatment to cruel and unusual punishment as defined under the Fifth, Eighth and 14th Amendments to the Constitution....

(emphasis added). - 1 2 3 Kennedy v. Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144, 160 (1963) (citation and internal quotation marks omitted); see also Arizona v. United States, 567 U.S. 387, 395 (2012) ("Perceived mistreatment of aliens in the United States may lead to harmful reciprocal treatment of American citizens abroad.").

- 1 2 3 4 5 "60 FR 7885: ANTI-DISCRIMINATION" (PDF). U.S. Government Publishing Office. February 10, 1995. p. 7888. Retrieved 2018-07-16. See also Zuniga-Perez v. Sessions, ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 17-996, p.11 (2d Cir. July 25, 2018) ("The Constitution protects both citizens and non‐citizens.") (emphasis added).

- ↑ "USCIS Announces Redesigned Green Card: Fact Sheet and FAQ". AILA. May 11, 2010. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- ↑ "New Design: The Green Card Goes Green". USCIS. May 11, 2010. Retrieved 2014-04-23.

- 1 2 Campos v. United States, 888 F.3d 724, 732 (5th Cir. 2018).

- ↑ INA § 264(e), ("Personal possession of registration or receipt card; penalties"); see also Davila v. United States, 247 F.Supp.3d 650, 656 (W.D. Pa. 2017) (lawsuit involving a U.S. citizen who was mistakenly arrested and detained by the U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE)).

- ↑ Agor v. Sessions, No. 17‐3231 (2d Cir. Sept. 26, 2018).

- ↑ ("Limit on injunctive relief'); Jennings v. Rodriguez, 583 U.S. ___, 138 S.Ct. 830, 875 (2018); Wheaton College v. Burwell, 134 S.Ct. 2806, 2810-11 (2014) ("Under our precedents, an injunction is appropriate only if (1) it is necessary or appropriate in aid of our jurisdiction, and (2) the legal rights at issue are indisputably clear.") (internal quotation marks and brackets omitted); Lux v. Rodrigues, 561 U.S. 1306, 1308 (2010); Correctional Services Corp. v. Malesko, 534 U.S. 61, 74 (2001) (stating that "injunctive relief has long been recognized as the proper means for preventing entities from acting unconstitutionally."); Nken v. Holder, 556 U.S. 418, 443 (2009); see also Alli v. Decker, 650 F.3d 1007, 1010-11 (3d Cir. 2011); Andreiu v. Ashcroft, 253 F.3d 477, 482-85 (9th Cir. 2001) (en banc).

- 1 2 (emphasis added); see also ("The term 'national of the United States' means (A) a citizen of the United States, or (B) a person who, though not a citizen of the United States, owes permanent allegiance to the United States.") (emphasis added); ("The term 'permanent' means a relationship of continuing or lasting nature, as distinguished from temporary, but a relationship may be permanent even though it is one that may be dissolved eventually at the instance either of the United States or of the individual, in accordance with law."); ("The term 'residence' means the place of general abode; the place of general abode of a person means his principal, actual dwelling place in fact, without regard to intent."); Black's Law Dictionary at p.87 (9th ed., 2009) (defining the term "permanent allegiance" as "[t]he lasting allegiance owed to [the United States] by its citizens or [permanent resident]s.") (emphasis added); Ricketts v. Attorney General of the U.S., ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 16-3182, p.5 note 3 (3d Cir. July 30, 2018) ("Citizenship and nationality are not synonymous."); Jennings v. Rodriguez, 138 S.Ct. 830, 855-56 (2018) (Justice Thomas concurring) ("The term 'or' is almost always disjunctive, that is, the words it connects are to be given separate meanings."); Chalmers v. Shalala, 23 F.3d 752, 755 (3d Cir. 1994) (same); Mobin v. Taylor, 598 F.Supp.2d 777, 783-84 (E.D. Va. 2009) (same); Matter of Rotimi, 24 I&N Dec. 567, 569-70 n.2 (BIA 2008) (same).

- 1 2 Ahmadi v. Ashcroft, et al., No. 03-249 (E.D. Pa. Feb. 19, 2003) ("Petitioner in this habeas corpus proceeding, entered the United States on September 30, 1982 as a refugee from his native Afghanistan. Two years later, the Immigration and Naturalization Service (the 'INS') adjusted Petitioner's status to that of a lawful permanent resident.... The INS timely appealed the Immigration Judge's decision to the Board of Immigration Appeals (the 'BIA').") (Baylson, District Judge); Ahmadi v. Att’y Gen., 659 F. App’x 72 (3d Cir. 2016) (Slip Opinion, pp.2, 4 n.1) (invoking statutorily nullified case law, the court dismissed an obvious illegal deportation case by asserting that it lacks jurisdiction to get to the merit of the claim solely due to ) (non-precedential); Ahmadi v. Sessions, No. 16-73974 (9th Cir. Apr. 25, 2017) (same; unpublished single-paragraph order); Ahmadi v. Sessions, No. 17-2672 (2d Cir. Feb. 22, 2018) (same; unpublished single-paragraph order); cf. United States v. Wong, 575 U.S. ___, ___, 135 S.Ct. 1625, 1632 (2015) ("In recent years, we have repeatedly held that procedural rules, including time bars, cabin a court's power only if Congress has clearly stated as much. Absent such a clear statement, ... courts should treat the restriction as nonjurisdictional.... And in applying that clear statement rule, we have made plain that most time bars are nonjurisdictional.") (citations, internal quotation marks, and brackets omitted) (emphasis added); see also Bibiano v. Lynch, 834 F.3d 966, 971 (9th Cir. 2016) ("Section 1252(b)(2) is a non-jurisdictional venue statute") (collecting cases) (emphasis added); Andreiu v. Ashcroft, 253 F.3d 477, 482 (9th Cir. 2001) (en banc) (the court clarified "that § 1252(f)(2)'s standard for granting injunctive relief in removal proceedings trumps any contrary provision elsewhere in the law.").

- 1 2 3 ("The term 'refugee' means ... any person who is outside any country of such person’s nationality or, in the case of a person having no nationality, is outside any country in which such person last habitually resided, and who is unable ... to return to, and is unable ... to avail himself ... of the protection of, that country because of persecution ... on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion....") (emphasis added).

- ↑ Federis, Marnette (March 3, 2018). "Some Vietnamese immigrants were protected from deportation, but the Trump administration may be changing that policy". Public Radio International (PRI). Retrieved 2018-09-23.

- ↑ Levin, Sam (November 10, 2017). "Detained and divided: how the US turned on Vietnamese refugees". The Guardian. Retrieved 2018-09-23.

- ↑ ("Nationals but not citizens of the United States at birth"); see also 8 U.S.C. § 1436.

- 1 2 3 4 Alabama v. Bozeman, 533 U.S. 146, 153 (2001) ("The word 'shall' is ordinarily the language of command.") (internal quotation marks omitted).

- ↑ Ricketts v. Attorney General of the U.S., ___ F.3d ___, ___, No. 16-3182, p.2 (3d Cir. July 30, 2018).

- ↑ ("Treatment of nationality claims"); see also ("In the case of an alien who makes a false ... claim of citizenship, or who registers to vote or votes in a Federal, State, or local election (including an initiative, recall, or referendum) in violation of a lawful restriction of such registration or voting to citizens, if each natural parent of the alien (or, in the case of an adopted alien, each adoptive parent of the alien) is or was a citizen (whether by birth or naturalization), the alien permanently resided in the United States prior to attaining the age of 16, and the alien reasonably believed at the time of such ... claim, or violation that he or she was a citizen, no finding that the alien is, or was, not of good moral character may be made based on it.").

- ↑ United States v. Lanier, 520 U.S. 259, 264-65 n.3 (1997) (internal quotation marks omitted).

- ↑ "I Am a Permanent Resident. How Do I Help My Relative Become a U.S. Permanent Resident?" (PDF). USCIS. Retrieved September 23, 2018.

- ↑ Visa Bulletins Archived 2014-01-01 at the Wayback Machine. State Department

- ↑ Check Case Processing Times USCIS

- ↑ 8 C.F.R. 316.2; 8 U.S.C. § 1427; 8 U.S.C. § 1429

- ↑ See8 C.F.R. 319

- ↑ "Citizenship and Assimilation Grant Program". USCIS. Retrieved September 22, 2018.

- ↑ "Green Card". USCIS. Retrieved 2018-09-23.

- 1 2 3 4 Visa Bulletin for October 2013 U.S. State Dept Visa Bulletin October 2013

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Visa Bulletin for September 2012". USCIS. Archived from the original on 2012-08-15.

- ↑ "Visa Bulletin For October 2015".

- ↑ "Why many rich Chinese don't live in China". The Economist. Retrieved 2018-06-12.

- 1 2 "Humanitarian Immigration Programs, Providing Immigration Benefits & Information". U.S. Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ "Presidential Determination on FY 2007 Refugee Admissions Numbers". Office of the Press Secretary, the White House. 2006-10-11. Retrieved 2007-01-05.

- ↑ See the U.S. Department of State Visa Bulletins Archived 2014-01-01 at the Wayback Machine. and USCIS Processing Dates for details.

- ↑ "Our History". USCIS. May 25, 2011. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ↑ National Visa Center, U.S. Department of State, retrieved December 3, 2007

- ↑ Application To Register Permanent Residence or Adjust Status, form I-485, USCIS Website, retrieved on December 3, 2007

- ↑ Application for Travel Document, Documentation for form I-131, USCIS Website, retrieved December 3, 2007

- ↑ Employment Authorization, US Immigration Website, retrieved September 19, 2016

- ↑ Application for Employment Authorization, Documentation for form I-765, USCIS Website, retrieved December 3, 2007

- ↑ "Visa Bulletin". Travel.state.gov. Archived from the original on 2012-03-14. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ "USCIS – I-130, Petition for Alien Relative". Uscis.gov. 2012-01-01. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ "I Married an Alien, Get Us Out of Here: Immigrant Visas for Spouses of US Citizens Living in the United Kingdom". Usvisalawyers.co.uk. 2012-12-11. Retrieved 2012-12-30.

- ↑ "A Beginner's Guide to the Affidavit of Support". Usvisalawyers.co.uk. 2012-02-14. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ "Family of Green Card Holders (Permanent Residents)". U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services.

- ↑ "Millions stay in green-card limbo". The Augusta Chronicle. 13 December 2006.

- ↑ "Permanent Labor Certification". Employment and Training Administration, US Department of Labor. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ "What is Schedule A and who qualifies? OFLC Frequently Asked Questions and Answers". Employment and Training Administration, U.S. Department of Labor. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ Immigrant Petition for Alien Worker, form I-140, USCIS Website, retrieved on December 3, 2007

- ↑ "Employment-Based Visas". US Department of State. Archived from the original on 2006-12-30. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ "Immigration Statistics". US Department of Homeland Security. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ Visa Bulletin, US Department of State, retrieved on December 3, 2007

- ↑ October 2006, fall 2006.pdf Business Immigration Review, Issue Fall 2006, Immigration Support Services, retrieved December 3, 2007

- ↑ Medical Examination of Aliens Seeking Adjustment of Status, form I-693 description, USCIS Website, retrieved December 3, 2007

- ↑ http://blog.uscis.gov/2011/03/e-mail-scam-avoid-green-card-lottery.html

- ↑ "The Beacon: E-mail Scam: Avoid Green Card Lottery Fraud". Blog.uscis.gov. 2011-03-02. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ "Website Fraud Warning". US Department of State. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- ↑ "FTC Consumer Alert: Diversity Visa Lottery: Read the Rules, Avoid the Rip-Offs". Federal Trade Commission. Retrieved 2006-12-31.

- 1 2 Bruno, Andorra (2001-08-22), " Immigration: Registry as Means of Obtaining Lawful Permanent Residence (CRS Report for Congress), Congressional Research Service

- 1 2 Holtzman, Alexander Thomas (2015-01-01), A Modest Proposal: Legalize Millions of Undocumented Immigrants with the Change of a Single Statutory Date, SSRN 2561911

- ↑ form I-751, USCIS Website, retrieved on December 3, 2007

- ↑ form I-829, USCIS Website, retrieved December 3, 2007

- ↑ , "Legal List of acceptable Green Card evidence"

- ↑ 8 C.F.R. 1216.1 ("Definition of conditional permanent resident").

- ↑ "London US Embassy website". London.usembassy.gov. 2012-02-10. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ "Maintaining US Lawful Permanent Resident Status". usvisalawyers.co.uk. 2014-10-23. Retrieved 2014-10-23.

- ↑ Returning Resident Visas U.S. Department of State, retrieved April 28, 2011

- ↑ "How to Renew a Green Card". immigrationamerica.org.

- ↑ "Giving Up US Citizenship: Is It Right for You?". Gudeon & McFadden. Retrieved 20 May 2016.

- ↑ United States: HEART Act Applicable To Expatriates And Long-Term Residents McDermott Will and Emery

- ↑ "''Expatriate Rules in HEART'' Deloitte". Benefitslink.com. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services. "myUSCIS - Case Status Search". Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- ↑ International Civil Aviation Organization (2015). "Doc 9303: Machine Readable Travel Documents, Part 5: Specifications for TD1 Size Machine Readable Official Travel Documents (MROTDs)" (PDF) (Seventh ed.). p. 13. ISBN 978-92-9249-794-1. Retrieved 2017-01-31.

- ↑ "Visas: Documentation of Immigrants and Nonimmigrants — Visa Classification Symbols" (PDF). Federal Register. 73 (55): 14926. March 20, 2008. Retrieved 2012-02-20.

- ↑ "SI 00502.215 The Affidavits of Support". Secure.ssa.gov. 2009-01-27. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ "U.S. Department of State Foreign Affairs Manual Volume 9 – Visas". Retrieved 2016-02-25.

- ↑ "U.S. issues redesigned, RFID-enhanced 'green cards'". fcw.com. 2010-05-13. Retrieved 2012-05-08.

- ↑ "RFID Hacking - Live Free or RFID Hard" (PDF). Black Hat USA 2013 – Las Vegas, NV. 2013-08-01. p. 49. Retrieved 2017-01-30.

- ↑ "Passports & Visas Requirements – Do I Need a Visa?". Costa Rica. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ "Embassy of the Dominican Republic, in the United States". Domrep.org. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ Mambo Open Source Project. "Embassy of Mexico in India". Portal.sre.gob.mx. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ "Visas, Passports, etc". Nyconsul.com. 2009-07-21. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ "Entering The Bahamas". The Bahamas.

- ↑ "Immigration". Gov.bm. 2008-05-22. Archived from the original on 2007-10-17. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ "Does a Permanent Resident Need a Visa for the Virgin Islands?". Retrieved 2014-09-12.

- ↑ "Countries/Territories requiring visas". Cic.gc.ca. 2011-07-11. Retrieved 2012-04-05.

- ↑ Branch, Government of Canada, Citizenship and Immigration Canada, Communications. "Do I need a visa to visit Canada?".

- ↑ "Nationalities not required to obtain a visa & the visa waiver programme". government.nl.

- ↑ "Visa Consular | Embajada de Costa Rica en DC". www.costarica-embassy.org. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "List of Countries". www.immigration.gov.ky. Retrieved 2017-12-30.

- ↑ "Embassy of the Dominican Republic, in the United States". Domrep.org. Retrieved 2014-08-16.

- ↑ "Instituto Nacional de Migracion". www.inm.gob.mx. Retrieved 2015-08-04.

- ↑ "Embassy of the Republic of Serbia in the USA".

- ↑ "Embassy of the Republic Kosovo, in Washington DC".

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Green Cards (United States). |