USS Princeton (1843)

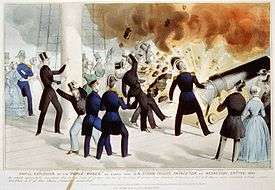

.jpg) Lithograph of Princeton, by Nathaniel Currier, 1844 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Princeton |

| Namesake: | Princeton, a borough in New Jersey |

| Ordered: | November 18, 1841 |

| Laid down: | October 20, 1842 |

| Launched: | September 5, 1843 |

| Commissioned: | September 9, 1843 |

| Fate: | Broken up, October 1849 |

| General characteristics | |

| Displacement: | 954 long tons (969 t) |

| Length: | 164 ft (50 m) |

| Beam: | 30 ft 6 in (9.30 m) |

| Draft: | 17 ft (5.2 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sail and steam |

| Speed: | 7 kn (8.1 mph; 13 km/h) |

| Complement: | 166 officers and enlisted |

| Armament: | 2 × 12 in (300 mm) smoothbore guns, 12 × 42 pdr (19 kg) carronades |

The first USS Princeton was a screw steam warship in the United States Navy. Commanded by Captain Robert F. Stockton, Princeton was launched on September 5, 1843.

The ship's reputation in the Navy never recovered from a devastating incident early in her service. On February 28, 1844, during a Potomac River pleasure cruise for dignitaries that included a demonstration of her two heavy guns, one gun exploded killing six people, including Secretary of State Abel P. Upshur, Secretary of the Navy Thomas Walker Gilmer, and other high-ranking federal officials. President John Tyler, who was aboard but below decks, was not injured.

Early history

Princeton was laid down on October 20, 1842, at the Philadelphia Navy Yard as a 700 long tons (710 t) corvette. The designer of the ship and main supervisor of construction was the Swedish inventor John Ericsson, who later designed the USS Monitor. The construction was partly supervised by Captain Stockton who had secured the political support for the construction of the ship. The ship was named after Princeton, New Jersey, site of an American victory in the Revolutionary War and hometown of the prominent Stockton family. The ship was christened with a bottle of American whiskey and launched on September 5, 1843. It was ordered commissioned on September 9, 1843, with Captain Stockton in command.

Princeton made a trial trip in the Delaware River on October 12, 1843. She departed Philadelphia on October 17 for a sea trial, proceeded to New York, where she engaged in a speed contest with the British steamer SS Great Western, besting her handily, and thence returned to Philadelphia on October 20 to finish outfitting. On November 22, Captain Stockton reported "Princeton will be ready for sea in a week." On November 28, he dressed ship and received visitors on board for inspection. On November 30, she towed the USS Raritan down the Delaware and later returned to the Philadelphia Navy Yard. Princeton sailed on January 1, 1844, for New York, where she received her two big guns, named Peacemaker and Oregon. Princeton was sent to Washington, D.C., in late January, arriving on February 13. Washingtonians displayed great interest in the ship and her guns. She made trial trips with passengers on board down the Potomac River on February 16, 18, and 20, during which the Peacemaker was fired several times.[1] The Tyler administration promoted the ship as part of its campaign for naval expansion and Congress adjourned for February 20 so that members could tour the ship. Former President John Quincy Adams, now a congressman and skeptical of both territorial expansion and the armaments required to support it, said the Navy welcomed politicians "to fire their souls with patriotic ardor for a naval war".[2][3]

Design

The machinery

Princeton included the very first screw propellers powered by an engine mounted entirely below the waterline to avoid the vulnerability of paddle wheels and higher engines to gunfire.[4] Her two vibrating lever engines were built by Merrick & Towne,[lower-alpha 1] and designed by Ericsson. They burned hard coal and drove a six-bladed screw 14 ft (4.3 m) in diameter. The engine was small enough to be below the waterline. Ericsson also designed the ship's collapsible funnel, an improved range-finder, and recoil systems for the main guns.

The guns

Twelve 42-pound (19 kg) carronades were mounted within the ship's iron hull. Ericsson had designed the ship to mount one long gun, named the Oregon, built in England using modern technology to fire 225-pound (102 kg) 12 in (300 mm) diameter shot. Captain Stockton wanted his ship to carry two long guns and had the second, named Peacemaker, built in Philadelphia. The two guns fired identical shot, but the Peacemaker was built with older forging technology creating a larger gun of more impressive appearance, but lower strength.[8] Both guns were mounted onto the Princeton. Though the Oregon had undergone intensive testing and had been reinforced to prevent cracks detrimental to the integrity of the cannon, Stockton rushed the Peacemaker and mounted it without much testing. According to Kilner, the Peacemaker was "fired only five times before certifying it as accurate and fully proofed."

The Oregon, originally named The Orator, was a smooth bore muzzle loader (ML) made out of wrought iron and was capable of firing a shot 5 mi (8.0 km) using a 50 lb (23 kg) charge. It was manufactured at the Mersey Iron Works in Liverpool, England, and shipped to the U.S. in 1841. The design was revolutionary in that it used the "built-up construction" of placing red-hot iron hoops around the breech-end of the weapon, which pre-tensioned the gun and greatly increased the charge the breech could withstand.

The Peacemaker was another 12 in (300 mm) muzzle loader made by Hogg and DeLamater of New York City, under the designs and direction of Captain Stockton. Attempting to copy the Oregon, but not understanding the importance of Ericsson's hoop construction, Stockton instead heavily reinforced it at the breech simply by making the metal of the gun thicker, ending up with a weight of more than 27,000 lb (12,000 kg). This produced a gun that had the typical weakness of a wrought iron gun, the breech being unable to withstand the transverse forces of the charge. This meant it was almost certain to burst at some point.

1844 Peacemaker accident

President Tyler hosted a public reception for Stockton in the East Room of the White House on February 27, 1844.[9] On February 28, USS Princeton departed Alexandria, Virginia, on a pleasure and demonstration cruise down the Potomac with President John Tyler, members of his Cabinet, former First Lady Dolley Madison, Senator Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri, and approximately four hundred guests on board. Captain Stockton decided to fire the larger of her two long guns, Peacemaker, to impress his guests. Peacemaker was fired three times on the trip downriver and was loaded to fire a salute to George Washington as the ship passed Mount Vernon on the return trip. The guests aboard viewed the first set of firings and then retired below decks for lunch and refreshments.[10]

Secretary Gilmer urged those aboard to view a final shot with the Peacemaker. When Captain Stockton pulled the firing lanyard, the gun burst. Its left side had failed, spraying hot metal across the deck[8] and shrapnel into the crowd. Instantly killed were Navy Secretary Gilmer; Secretary of State Upshur; Captain Beverley Kennon,[lower-alpha 2] who was Chief of the Bureau of Construction, Equipment and Repairs; Virgil Maxcy, a Maryland attorney with decades of experience as a state and federal officeholder;[lower-alpha 3] David Gardiner,[lower-alpha 4] a New York lawyer and politician; and the President's valet, a black slave named Armistead.[lower-alpha 5] Another sixteen to twenty people were injured, including several members of the ship's crew, Senator Benton, and Captain Stockton.[14][15] The President was below decks and not injured.[16]

Aftermath

Rather than ascribe responsibility for the explosion to individuals, Tyler wrote to Congress the next day that the disaster "must be set down as one of the casualties which, to a greater or lesser degree, attend upon every service, and which are invariably incident to the temporal affairs of mankind".[17] He said it should not be allowed to impact their positive assessment of Stockton and his improvements in ship construction.[18]

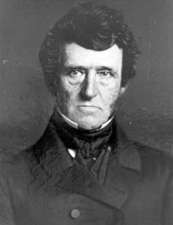

Capt. Robert Stockton |

President John Tyler |

First Lady Julia Tyler |

Plans to construct more ships modeled on the Princeton were promptly scrapped, but Tyler won Congressional approval for the construction of a single gun on the dimensions of the Peacemaker, which was fired once and never mounted.[18] A Court of Inquiry investigated the cause of the explosion and found that all those involved had taken appropriate precautions.[18][lower-alpha 6] At Stockton's request, the Committee on Science and Arts of the Franklin Institute conducted its own inquiry, which criticized many details of the manufacturing process, as well as the use of welded band for reinforcement rather than the shrinking technique used on the Oregon.[18] Ericsson, whom Stockton had originally paid $1,150 for designing and outfitting the Princeton, sought another $15,000 for his additional efforts and expertise. He sued Stockton for payment and won in court, but the funds were never appropriated.[18] Stockton went on to serve as Military Governor of California and a United States Senator from New Jersey.[19] Ericsson had a distinguished career in naval design and is best known for his work on the USS Monitor, the U.S. Navy's first ironclad warship.

To succeed Gilmer as Secretary of the Navy, Tyler appointed John Y. Mason, another Virginian.[8] As his new Secretary of State, Tyler named John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, like his predecessor an advocate of states rights, nullification of federal law by states, the annexation of Texas, and its admission into the union as a slave state.[20][lower-alpha 7] But where Gilmer and Upshur had supported annexation as a national cause, Calhoun recast the political discussion. To Tyler's frustration, he promoted the annexation of Texas while "directly, unambiguously, and full-throatedly celebrating slavery and celebrating sectional advantage", that is, the importance of Texas to the longterm survival of slavery in the United States.[20][21] Upshur was about to win Senate approval of a treaty annexing Texas when he died. Under Calhoun annexation was delayed and became a principal issue in the presidential election of 1844.[22]

Julia Gardiner, who was below deck on the Princeton when her father David died in the Peacemaker explosion, became First Lady of the United States four months later. She had declined President Tyler's marriage proposal a year earlier, and sometime in 1843 they agreed they would marry but set no date. The President had lost his first wife in September 1842, and at the time of the explosion he was almost 54. Julia was not yet 24. She later explained that her father's death changed her feelings for the President: "After I lost my father I felt differently toward the President. He seemed to fill the place and to be more agreeable in every way than any younger man ever was or could be."[23] Because he had been widowed less than two years and her father had died so recently, they married in the presence of just a few family members in New York City on June 26, 1844. A public announcement followed the ceremony.[24] They had seven children before Tyler died in 1862, and his wife never remarried. In 1888, Julia Gardiner told journalist Nelly Bly that at the moment of the Peacemaker explosion "I fainted and did not revive until someone was carrying me off the boat, and I struggled so that I almost knocked us both off the gangplank". She said she later learned that President Tyler was her rescuer.[25][lower-alpha 8] Some historians question her account.[26]

The Peacemaker disaster prompted a reexamination of the process used to manufacture cannons. This led to the development of new techniques that produced cannons that were stronger and more structurally sound, such as the system pioneered by Thomas Rodman.

Later history

During construction and in the years following, Stockton attempted to claim complete credit for the design and construction of Princeton.

_Bell.jpg)

Princeton was employed with the Home Squadron from 1845 to 1847. She later served in the Mediterranean from August 17, 1847, to June 24, 1849. Upon her return from Europe, she was surveyed and found to be in need of 68,000 dollars ($2 million in present-day terms) in repairs to return her to complete order. The price was deemed unacceptable and a second survey was ordered.[27] She was condemned due to her decaying timber and broken up at the Boston Navy Yard that October and November.[28][29]

Legacy

In 1851, her "Ericsson semi-cylinder" design engines, and some usable timbers, were incorporated in the construction of the second Princeton.[30]

The Oregon is on display inside the main gate of the United States Naval Academy in Annapolis, Maryland.[31]

The ship's bell was displayed during the 1907 Jamestown Exposition.[32] It was later installed in the porch of Princeton University's Thomson Hall,[33] which was constructed as a private residence in 1825 by Robert Stockton's father Richard.[34] It is currently on outside display at the Princeton Battle Monument, near Princeton's borough hall.[35]

Notes

- ↑ Merrick & Towne was a foundry based in Philadelphia, founded by John Henry Towne and a Mr. S. V. Verrick,[5] and also notable for building the engines of the USS Mississippi.[6] It was later renamed Merrick & Sons.[7]

- ↑ Beverley Kennon (1793–1844) served in the U.S Navy and saw action during the Second Barbary War (1815–1816). He had command of several ships beginning in 1830 and then was given responsibility for the Washington Navy Yard from April 1841 to March 1843, when he became Chief of the Navy's Bureau of Construction, Equipment and Repairs. He was a lifelong friend of Upshur.[11]

- ↑ Born in 1785, his federal career included service as Solicitor of the U.S. Treasury from 1830 to 1837 and Chargé d'Affaires to Belgium from 1837 to 1842. He was a political ally of Calhoun and an advocate of the resettlement of free blacks in Africa.

- ↑ He managed the property his wealthy wife had inherited and had served for four years in the New York State Senate. Contemporaneous accounts refer to him as Colonel David Gardiner, but that was an error. His son, David L. Gardiner, had recently been appointed Tyler's aide-de-camp with the rank of colonel.[12]

- ↑ Congressman George Sykes of New Jersey, an eyewitness, described Armistead as "a stout black man about 23 or 24 years old" and reported that he lived for short while after the explosion and that "neither the surgeon of the Princeton nor any other person could discover the slightest wound or injury about him".[13]

- ↑ "The court found that every precaution skill could devise had been taken."[18]

- ↑ "The Texas matter was far advanced when Calhoun entered the State Department. Upshur and the [Texas] Republic's representatives in Washington had already worked out the main lines of an agreement between the two countries. The new Secretary of State, a longtime proponent of adding Texas to the United States, swiftly completed the task."[20]

- ↑ The interview appeared in the New York World on October 28, 1888.[26]

References

- This article incorporates text from the public domain Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships. The entry can be found here.

- ↑ Walters, Kerry S. (2013). "Explosion on the Potomac: The 1844 Calamity Aboard the USS Princeton". Charleston. SC: The History Press. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ↑ Karp, Matthew (2016). This Vast Southern Empire: Slaveholders at the Helm of American Foreign Policy. Harvard University Press. pp. 92–3.

- ↑ Adams, John Quincy (1876). Adams, Charles Francis, ed. Memoirs of John Quincy Adams: Comprising Portions of His Diary from 1795 to 1848. 11. Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott & Co. pp. 515–6.

- ↑ Rayback, Robert J. (1992). Millard Fillmore: Biography of a President. Newtown, Connecticut: American Political Biography Press. p. 300. ISBN 0945707045.

- ↑ Hubbard, Edwin (1880). The Towne Family Memorial. Fergus Printing Company. pp. 88–90.

- ↑ Bauer, Karl Jack Bauer; Roberts, Stephen S. (1991). Register of Ships of the U.S. Navy, 1775-1990: Major Combatants. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 53–54. ISBN 978-0313262029.

- ↑ Goodwin, Daniel R. (December 16, 1870). "Obituary Notice of Samuel Vaughan Merrick, Esq". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 11: 584–596.

- 1 2 3 Taylor, John M. (1984). "The Princeton Disaster". Proceedings. United States Naval Institute. 110 (9): 148–9. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Karp, 'Vast Southern Empire, p. 93

- ↑ Blackman, Ann (September 2005). "Fatal Cruise of the Princeton". Naval History. Reprinted by Military.com. Retrieved January 2, 2014.

- ↑ The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. IV. New York: James T. White & Company. 1897. p. 552. Retrieved March 15, 2017.

- ↑ "Obituary, David L. Gardiner" (PDF). New York Times. New York, NY. May 10, 1892.

- ↑ Holland, Jesse J. (2016). The Invisibles: The Untold Story of African American Slaves in the White House. Guilford, Connecticut: Lyons Press. pp. 175–78.

- ↑ United States Congress (1844). Accident on Steam-ship "Princeton"...: Report [of] the Committee on Naval Affairs.

- ↑ "Further Particulars of the Accident on Board the Princeton". Baltimore Sun. Baltimore, MD. March 1, 1844. p. 1. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Merry, Robert W. (2009). A Country of Vast Designs: James K. Polk, the Mexican War, and the Conquest of the American Continent (1st ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 65–66. ISBN 978-0743297431.

- ↑ Evan, William M.; Manion, Mark (2002). Minding the Machines: Preventing Technological Disasters. Prentice Hall. p. 216. ISBN 978-0130656469. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pearson, Lee M. (Spring 1966). "The "Princeton" and the "Peacemaker": A Study in Nineteenth-Century Naval Research and Development Procedures". Technology and Culture. Johns Hopkins University Press and the Society for the History of Technology. 7 (2): 163–83. JSTOR 3102081.

- ↑ "Biography, Robert F. Stockton". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. The Historian of the United States Senate. Retrieved September 22, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Silbey, Joel H. (2005). Storm over Texas: The Annexation Controversy and the Road to Civil War. Oxford University Press. pp. 39–41. ISBN 978-0198031925. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ Crapol, Edward P. (2006). John Tyler, the Accidental President. University of North Carolina Press. pp. 209ff, 226. ISBN 978-0807872239. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

John Tyler consistently had maintained that throughout the Texas venture, beginning with the secret diplomacy of Abel P. Upshur, that national interests, not narrow sectional concerns, were the uppermost consideration in his quest for annexation.

- ↑ Karp, Vast Southern Empire, pp. 93ff

- ↑ Schneider, Dorothy; Schneider, Carl J. (2010). First Ladies: A Biographical Dictionary (3rd ed.). Facts on File. pp. 62ff. ISBN 978-1438127507. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ↑ Walters, Kerry (October 23, 2013). "An Explosion That Changed The Nation". Huffington Post. Retrieved September 1, 2016.

- ↑ Knutson, Lawrence L. "D.C. Disaster Concluded in a Romance". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved February 10, 2016.

- 1 2 Wead, Doug (2003). All the Presidents' Children: Triumph and Tragedy in the Lives of America's First Families. Atria Books. p. 406. Retrieved March 21, 2017.

- ↑ "The Steam-Frigate Princeton". The Republic. Washington D.C. September 10, 1849. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Steam Frigate Princeton". Richmond Enquirer. Richmond, Virginia. October 26, 1849. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ↑ "The Princeton". Wilmington Journal. Wilmington, N.C. November 23, 1849. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ↑ "Princeton II (Screw Steamer)". DANFS. U. S. Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

- ↑ Symonds, Craig L. (2005). Decision at Sea: Five Naval Battles That Shaped American History. Oxford University Press. p. 100n. Retrieved March 29, 2017.

- ↑ "NH 2082-A Bell of USS Princeton (1843-1849)". NH Series. U. S. Naval History and Heritage Command. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

On exhibit at the Jamestown Exposition, Hampton Roads, Virginia, 1907.

- ↑ "Can't You Hear". Princeton Alumni Weekly. 30 (16): 430. January 31, 1930. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ M. Halsey Thomas (1971). "Princeton in 1874: A Bird's Eye View". Princeton History. 1. Retrieved March 20, 2017.

- ↑ "The Princeton Bell". Historical Marker database. Retrieved February 11, 2016.

Further reading

- Beach, Edward L. (1986). The United States Navy : 200 years (1st ed.). New York: Henry Holt and Company. pp. 196–221. ISBN 978-0030447112.

- Canney, Donald L. (1998). Lincoln's Navy: The Ships, Men and Organization, 1861–65. Naval Institute Press. p. 232.

- Chitwood, Oliver Perry (1964) [Orig. 1939, Appleton-Century]. John Tyler, Champion of the Old South. Russell & Russell. OCLC 424864.

- Kathryn Moore, The American President: A Complete History: Detailed Biographies, Historical Timelines, Inaugural Speeches (Fall River Press, 2007), 120.

- Kinard, Jeff, Artillery: An Illustrated History of its Impact (ABC Clio, 2007) 194–202.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to USS Princeton (1843). |

- "Fatal Cruise of the Princeton" by Ann Blackman, U.S. Naval Institute, September 2005

- USS Princeton (1843–1849), Naval Historical Center, Online Library of Selected Images