Merkel-cell carcinoma

| Merkel-cell carcinoma | |

|---|---|

| |

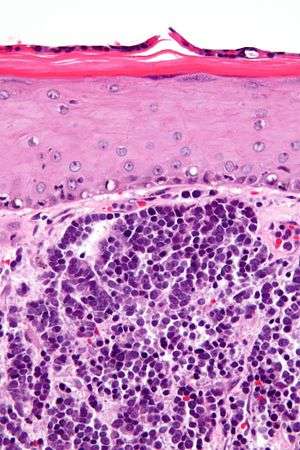

| Micrograph of a Merkel-cell carcinoma. H&E stain. | |

| Specialty | Oncology |

Merkel-cell carcinoma (MCC) is a rare and highly aggressive skin cancer, which, in most cases, is caused by the Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV) discovered by scientists at the University of Pittsburgh in 2008.[1] It is also known as cutaneous APUDoma, primary neuroendocrine carcinoma of the skin, primary small cell carcinoma of the skin, and trabecular carcinoma of the skin.[2]

About 80% of Merkel-cell carcinomas are caused by MCV. The virus is clonally integrated into the cancerous Merkel cells. In addition, the virus has a particular mutation only when found in cancer cells, but not when it is detected in healthy skin cells.[3] Direct evidence for this oncogenetic mechanism comes from research showing that inhibition of production of MCV proteins causes MCV-infected Merkel carcinoma cells to die but has no effect on malignant Merkel cells that are not infected with this virus.[4][5] MCV-uninfected tumors, which account for about 20% of Merkel-cell carcinomas, appear to have a separate and as-yet unknown cause.[6] Those tend to have extremely high genome mutation rates, due to ultraviolet light exposure, whereas MCV-infected Merkel cell carcinomas have low rates of genome mutation.[7]

Signs

Merkel-cell carcinoma (MCC) usually presents as a firm, painless, nodule (up to 2 cm diameter) or mass (>2 cm diameter). These flesh-colored, red, or blue tumors typically vary in size from 0.5 cm (less than one-quarter of an inch) to more than 5 cm (2 inches) in diameter, and usually enlarge rapidly. Although MCC's may arise almost anywhere on the body, about half originate on sun-exposed areas of the head and neck, one-third on the legs, and about one-sixth on the arms. In about 12% of cases, no obvious anatomical site of origin ("primary site") can be identified.[8] The most significant clues in the diagnosis of MCC were summarized 2008 in the acronym AEIOU (Asymptomatic/lack of tenderness, Expanding rapidly, Immune suppression, Older than 50 years, and Ultraviolet-exposed site on a person with fair skin).[9] Ninety percent of MCC´s have 3 or more of those features.[10] MCC is sometimes mistaken for other histological types of cancer, including basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, malignant melanoma, lymphoma, and small cell carcinoma, or as a benign cyst.[6] Merkel cell carcinomas have been described in children, however pediatric cases are very rare.[11]

Merkel-cell cancers tend to invade locally, infiltrating the underlying subcutaneous fat, fascia, and muscle, and typically metastasize early in their natural history, most often to the regional lymph nodes. MCCs also spread aggressively through the blood vessels to many organs, particularly to liver, lung, brain, and bone.[12]

Pathophysiology

Several factors are involved in the pathophysiology of MCC, including a virus called Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV), ultraviolet radiation (UV) exposure, and weakened immune function.

Merkel cell polyomavirus

MCV likely contributes to the development of the majority of MCC.[13] About 80% of MCC tumors are infected with MCV, with the virus integrated in a monoclonal pattern,[13] indicating that the infection was present in a precursor cell before it became cancerous. MCV, a polyomavirus, is the first polyomavirus strongly suspected to cause tumors in humans.[14] MCV is ubiquitous and is thought to be part of the human skin microbiome.[15] Intriguingly, most MCV viruses obtained so far from tumors have specific mutations that render the virus uninfectious.[3][16] MCC patients whose tumors contain MCV have higher antibody levels against the virus than similarly infected healthy adults.[17] A study of a large patient registry from Finland suggests that individuals with MCV-positive MCC's have better prognoses than do MCC patients without MCV infection.[18] Like other tumor viruses, most people who are infected with MCV do not develop MCC. As of 2008, it was unknown what other steps or co-factors were required for MCC-type cancers to develop.[19]

UV light

At least 20% of MCC tumors are not infected with MCV, suggesting that MCC may have other causes, especially sunlight or ultraviolet light as in a tanning beds. MCC can also occur together with other sun exposure-related skin cancers that are not infected with MCV (i.e. basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, melanoma). Ultraviolet radiation such as in sun exposure increases the risk in MCC development, consistent with the fact that MCCs occur more commonly in sun-exposed areas.[9][6]

Immunosuppression

The incidence of MCC is increased in conditions with defective immune functions such as malignancy, HIV infection, and organ transplant patients, etc.[1] Mutations in MCC occur more frequently than would otherwise be expected among immunosuppressed patients, such as transplant patients, AIDS patients, and the elderly, suggesting that the initiation and progression of the disease is modulated by the immune system.[9] While infection with MCV is common in humans,[20]

Diagnosis

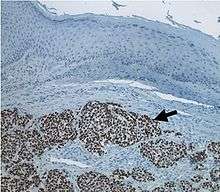

Definitive diagnosis of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) requires examination of biopsy tissue. An ideal biopsy specimen is either a punch biopsy or a full-thickness incisional biopsy of the skin including full-thickness dermis and subcutaneous fat. In addition to standard examination under light microscopy, immunohistochemistry (IHC) is also generally required to differentiate MCC from other morphologically similar tumors such as small cell lung cancer, the small cell variant of melanoma, various cutaneous leukemic/lymphoid neoplasms, and Ewing's sarcoma. Similarly, most experts recommend longitudinal imaging of the chest, typically a CT scan, to rule out that the possibility that the skin lesion is a skin metastasis of an underlying small cell carcinoma of the lung.

Prevention

Sunlight exposure is thought to be one of the causes of Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC). As a result, it is important to prevent the skin from excessive sun exposure. For example, following are some general rules for skin protection:[21] seek shade, especially around noon time. Cover exposed skin with broad-brimmed hat and clothing. Avoid UV tanning. Use broad spectrum sunscreen (UVA/UVB) with an SPF≥15. Apply sunscreen 30 minutes before outdoor activity and reapply every 2 hours. Regular self-examination of the skin should be done every month and a check once a year with a qualified dermatologist. Since reduced immune function is another contributing factor it is equally important to obtain proper nutrition and follow a healthy life style to boost immune function.[21]

Treatment

Early diagnosis and treatment of Merkel-cell cancers are important factors in decreasing the chance of metastasis, after which it is exceptionally difficult to cure.

Surgery

Surgery is usually the first treatment that a patient undergoes for Merkel-cell cancer, especially for the primary tumor.[22] As with surgery for most other forms of cancer, it is normal for the surgeon to remove a border of healthy tissue surrounding the tumor. Complete excision is associated with significant higher survival rates.[23] Due to the capability of vertical growth that may extend into muscle in MCC, Mohs surgery may also be helpful to provide local control.[24][25]

Radiation and chemotherapy

Because of MCC's aggressive local and regional metastatic behavior, radiotherapy is commonly used to treat Merkel-cell cancer. It has been shown to be effective in reducing the rates of recurrence and in increasing the survival of patients with MCC.[26] Radiation therapy can also be an alternative if MCC patients are not surgical candidate.[27]

Chemotherapy may be used to treat both primary and metastatic MCC. Although the definitive role of chemotherapy is unknown chemotherapy plays a role in the treatment, especially in MCC of head and neck regions.[28]

Sentinel lymph node biopsy

Sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) detects MCC spread in one third of patients whose tumors would have otherwise been clinically and radiologically understaged, and who may not have received treatment to the involved node bed. There was a significant benefit of adjuvant nodal therapy, but only when the SLNB was positive. Thus, SLNB is important for both prognosis and therapy and should be performed routinely for patients with MCC. In contrast, computed tomographic scans have poor sensitivity in detecting nodal disease as well as poor specificity in detecting distant disease.[29]

Drug therapy

As of 2013 there had been hope that new targeted anticancer therapy for patients with distant and systemic MCC disease would be available in the near future, particularly to target the MCV either to prevent infection or to inhibit viral-induced carcinogenesis.[30] In March 2017, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration granted accelerated approval to avelumab to treat adults and children above 12 years with metastatic MCC. Avelumab, a checkpoint-inhibitor targets the PD-1/PD-L1 pathway (proteins found on the body’s immune cells and some cancer cells) to help the body’s immune system attack cancer cells.[31]

National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines recommend PD-1 inhibitors, either nivolumab, pembrolizumab or avelumab, for patients with disseminated MCC;systemic therapy is not recommended for early stage MCC.[10]

Prognosis

Overall, the 5-year survival rate for Merkel cell carcinoma is around 60%. It varies depending on the stages of the cancer. In general, a higher cancer stage correlates with a lower survival rate. For example, National Cancer Data Base has survival rates collected from nearly 3000 MCC patients from year 1996-2000 with 5-year survival rates listed as follows:[32] Stage IA: 80%. Stage IB: 60%. Stage IIA: 60%. Stage IIB: 50%. Stage IIC: 50%. Stage IIIA: 45%. Stage IIIB: 25%. Stage IV: 20%. 5 yr survival may be 51% among patients with localized disease, 35% for those with nodal disease, and 14% with metastases to a distant site.[10]

Several other features may also affect prognosis, independent of tumor stage. They include MCV viral status, histological features, and immune status. In viral status, MCV large tumor antigen (LT antigen) and retinoblastoma protein (RB protein) expression correlates with more favorable prognosis, while p63 expression correlates with a poorer prognosis.[33][34] Histological features such as intratumoral CD8+ T lymphocyte infiltration may be associated with a favorable prognosis, while lymphovascular infiltrative pattern may be associated with a poorer prognosis.[35][36] Immune status, especially T cell immunosuppression (e.g., organ transplant, HIV infection, certain malignancy) predicts poorer prognosis and higher mortality.[37]

Epidemiology

This skin cancer occurs most often in Caucasians between 60 and 80 years of age, and its rate of incidence is about twice as high in males as in females. MCC is not a very common skin cancer. In 2013, the annual incidence rate was around 0.7 per 100,000 persons in the U.S.[38] As of 2005, roughly 2,500 new cases of MCC have been diagnosed each year in the United States,[38] as compared to around 60,000 new cases of malignant melanoma and over 1 million new cases of nonmelanoma skin cancer.[39] Similar to melanoma, the incidence of MCC in the US is increasing rapidly.[6]

Since 2006, it has been known that other primary cancers increase the risk of MCC significantly, especially in those with the prior multiple myeloma, chronic lymphocytic leukemia, and malignant melanoma.[40]

Immunosuppression can profoundly increase the odds of developing MCC. As of 2013, MCC occurred 30 times more often in people with chronic lymphocytic leukemia and 13.4 times more often in people with advanced HIV as compared to the general population; solid organ transplant recipients had a 10-fold increased risk compared to the general population.[26] A 2015 review of transplant recipients showed an up to 24-fold increased risk of MCC compared to the general population.[41]

Notable people who have had it

- Avigdor Arikha – Paris-based painter and art historian

- David Brudnoy – Boston talk radio host

- Al Copeland – New Orleans entrepreneur, powerboat racer

- Al Davis – Principal owner of the Oakland Raiders of the National Football League

- Ed Derwinski – U.S. Representative from Illinois and 1st Secretary of Veterans Affairs

- Leonard Hirshan – Showbusiness agent and manager.

- Max Perutz – Nobel Prize–winning chemist

- Lindsay Thompson – Former Premier of Victoria, Australia

- Joe Zawinul – Jazz-fusion keyboardist and composer

- John Fitch – Race car driver and road safety pioneer

- Carl Mundy – 30th Commandant of the United States Marine Corps

- Geoffrey Penwill Parsons – Pianist

- Maria Bueno - Tennis player[42]

References

- 1 2 Tello TL, Coggshall K, Yom SS, Yu SS (March 2018). "Merkel cell carcinoma: An update and review: Current and future therapy". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 78 (3): 445–454. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.12.004. PMID 29229573.

- ↑ Rapini RP, Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL (2007). Dermatology: 2-Volume Set. St. Louis: Mosby. ISBN 1-4160-2999-0.

- 1 2 Shuda M, Feng H, Kwun HJ, Rosen ST, Gjoerup O, Moore PS, Chang Y (October 2008). "T antigen mutations are a human tumor-specific signature for Merkel cell polyomavirus". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 105 (42): 16272–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0806526105. PMC 2551627. PMID 18812503.

- ↑ Houben R, Shuda M, Weinkam R, Schrama D, Feng H, Chang Y, Moore PS, Becker JC (July 2010). "Merkel cell polyomavirus-infected Merkel cell carcinoma cells require expression of viral T antigens". Journal of Virology. 84 (14): 7064–72. doi:10.1128/jvi.02400-09. PMC 2898224. PMID 20444890.

- ↑ Shuda M, Kwun HJ, Feng H, Chang Y, Moore PS (September 2011). "Human Merkel cell polyomavirus small T antigen is an oncoprotein targeting the 4E-BP1 translation regulator". The Journal of Clinical Investigation. 121 (9): 3623–34. doi:10.1172/jci46323. PMC 3163959. PMID 21841310.

- 1 2 3 4 Schrama D, Ugurel S, Becker JC (March 2012). "Merkel cell carcinoma: recent insights and new treatment options". Current Opinion in Oncology. 24 (2): 141–9. doi:10.1097/CCO.0b013e32834fc9fe. PMID 22234254.

- ↑ Wong SQ, Waldeck K, Vergara IA, Schröder J, Madore J, Wilmott JS, et al. (December 2015). "UV-Associated Mutations Underlie the Etiology of MCV-Negative Merkel Cell Carcinomas". Cancer Research. 75 (24): 5228–34. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1877. PMID 26627015.

- ↑ Deneve JL, Messina JL, Marzban SS et al. Merkel Cell Carcinoma of Unknown Primary Origin. Ann Surg Oncol 2012 Jan 21.

- 1 2 3 Heath M, Jaimes N, Lemos B, Mostaghimi A, Wang LC, Peñas PF, Nghiem P (March 2008). "Clinical characteristics of Merkel cell carcinoma at diagnosis in 195 patients: the AEIOU features". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 58 (3): 375–81. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2007.11.020. PMC 2335370. PMID 18280333.

- 1 2 3 Voelker R. Why Merkel Cell Cancer Is Garnering More Attention. JAMA. 2018;320(1):18–20. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7042

- ↑ https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaad.2018.08.021

- ↑ "Merkel Cell Carcinoma Treatment". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- 1 2 Amber K, McLeod MP, Nouri K (February 2013). "The Merkel cell polyomavirus and its involvement in Merkel cell carcinoma". Dermatologic Surgery. 39 (2): 232–8. doi:10.1111/dsu.12079. PMID 23387356.

- ↑ White MK, Pagano JS, Khalili K (July 2014). "Viruses and human cancers: a long road of discovery of molecular paradigms". Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 27 (3): 463–81. doi:10.1128/CMR.00124-13. PMC 4135891. PMID 24982317.

- ↑ Schowalter RM, Pastrana DV, Pumphrey KA, Moyer AL, Buck CB (June 2010). "Merkel cell polyomavirus and two previously unknown polyomaviruses are chronically shed from human skin". Cell Host & Microbe. 7 (6): 509–15. doi:10.1016/j.chom.2010.05.006. PMC 2919322. PMID 20542254.

- ↑ Sastre-Garau X, Peter M, Avril MF, Laude H, Couturier J, Rozenberg F, Almeida A, Boitier F, Carlotti A, Couturaud B, Dupin N (May 2009). "Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin: pathological and molecular evidence for a causative role of MCV in oncogenesis". The Journal of Pathology. 218 (1): 48–56. doi:10.1002/path.2532. PMID 19291712.

- ↑ Tolstov YL, Pastrana DV, Feng H, Becker JC, Jenkins FJ, Moschos S, Chang Y, Buck CB, Moore PS (September 2009). "Human Merkel cell polyomavirus infection II. MCV is a common human infection that can be detected by conformational capsid epitope immunoassays". International Journal of Cancer. 125 (6): 1250–6. doi:10.1002/ijc.24509. PMC 2747737. PMID 19499548.

- ↑ Sihto H, Kukko H, Koljonen V, Sankila R, Böhling T, Joensuu H (July 2009). "Clinical factors associated with Merkel cell polyomavirus infection in Merkel cell carcinoma". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 101 (13): 938–45. doi:10.1093/jnci/djp139. PMID 19535775.

- ↑ "New virus linked to rare but lethal skin cancer". The Age. Archived from the original on 2008-01-19. Retrieved 2008-02-26.

- ↑ Kean JM, Rao S, Wang M, Garcea RL (March 2009). "Seroepidemiology of human polyomaviruses". PLoS Pathogens. 5 (3): e1000363. doi:10.1371/journal.ppat.1000363. PMC 2655709. PMID 19325891.

- 1 2 "Merkel Cell Carcinoma - Prevention Guidelines - SkinCancer.org". www.skincancer.org. Retrieved 2018-03-04.

- ↑ Lebbe, Celeste; Becker, Jürgen C.; Grob, Jean-Jacques; Malvehy, Josep; Del Marmol, Veronique; Pehamberger, Hubert; Peris, Ketty; Saiag, Philippe; Middleton, Mark R. (November 2015). "Diagnosis and treatment of Merkel Cell Carcinoma. European consensus-based interdisciplinary guideline". European Journal of Cancer (Oxford, England: 1990). 51 (16): 2396–2403. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2015.06.131. ISSN 1879-0852. PMID 26257075.

- ↑ Tai, P. T.; Yu, E.; Tonita, J.; Gilchrist, J. (October 2000). "Merkel cell carcinoma of the skin". Journal of Cutaneous Medicine and Surgery. 4 (4): 186–195. doi:10.1177/120347540000400403. ISSN 1203-4754. PMID 11231196.

- ↑ O'Connor, W. J.; Roenigk, R. K.; Brodland, D. G. (October 1997). "Merkel cell carcinoma. Comparison of Mohs micrographic surgery and wide excision in eighty-six patients". Dermatologic Surgery: Official Publication for American Society for Dermatologic Surgery [et Al.] 23 (10): 929–933. ISSN 1076-0512. PMID 9357504.

- ↑ Boyer, John D.; Zitelli, John A.; Brodland, David G.; D'Angelo, Gina (December 2002). "Local control of primary Merkel cell carcinoma: review of 45 cases treated with Mohs micrographic surgery with and without adjuvant radiation". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 47 (6): 885–892. doi:10.1067/mjd.2002.125083. ISSN 0190-9622. PMID 12451374.

- 1 2 Hasan S, Liu L, Triplet J, Li Z, Mansur D (November 2013). "The role of postoperative radiation and chemoradiation in merkel cell carcinoma: a systematic review of the literature". Frontiers in Oncology. 3: 276. doi:10.3389/fonc.2013.00276. PMC 3827544. PMID 24294591.

- ↑ Harrington, Chris; Kwan, Winkle (October 2014). "Outcomes of Merkel cell carcinoma treated with radiotherapy without radical surgical excision". Annals of Surgical Oncology. 21 (11): 3401–3405. doi:10.1245/s10434-014-3757-8. ISSN 1534-4681. PMID 25001091.

- ↑ Chen, Michelle M.; Roman, Sanziana A.; Sosa, Julie A.; Judson, Benjamin L. (February 2015). "The role of adjuvant therapy in the management of head and neck merkel cell carcinoma: an analysis of 4815 patients". JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery. 141 (2): 137–141. doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2014.3052. ISSN 2168-619X. PMID 25474617.

- ↑ Gupta SG, Wang LC, Peñas PF, Gellenthin M, Lee SJ, Nghiem P (June 2006). "Sentinel lymph node biopsy for evaluation and treatment of patients with Merkel cell carcinoma: The Dana-Farber experience and meta-analysis of the literature". Archives of Dermatology. 142 (6): 685–90. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.6.685. PMID 16785370.

- ↑ Munde PB, Khandekar SP, Dive AM, Sharma A (September 2013). "Pathophysiology of merkel cell". Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 17 (3): 408–12. doi:10.4103/0973-029x.125208. PMID 24574661.

- ↑ FDA approves first treatment for rare form of skin cancer FDA News Release, March 23, 2017

- ↑ "Survival Rates for Merkel Cell Carcinoma, by Stage". www.cancer.org. Retrieved 2018-03-03.

- ↑ Sihto H, Kukko H, Koljonen V, Sankila R, Böhling T, Joensuu H (July 2011). "Merkel cell polyomavirus infection, large T antigen, retinoblastoma protein and outcome in Merkel cell carcinoma". Clinical Cancer Research. 17 (14): 4806–13. doi:10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-3363. PMID 21642382.

- ↑ Stetsenko GY, Malekirad J, Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Thibodeau RM, Nagase K, Schmidt M, Storer BE, Argenyi ZB, Nghiem P (December 2013). "p63 expression in Merkel cell carcinoma predicts poorer survival yet may have limited clinical utility". American Journal of Clinical Pathology. 140 (6): 838–44. doi:10.1309/AJCPE4PK6CTBNQJY. PMC 4074520. PMID 24225752.

- ↑ Paulson KG, Iyer JG, Tegeder AR, Thibodeau R, Schelter J, Koba S, Schrama D, Simonson WT, Lemos BD, Byrd DR, Koelle DM, Galloway DA, Leonard JH, Madeleine MM, Argenyi ZB, Disis ML, Becker JC, Cleary MA, Nghiem P (April 2011). "Transcriptome-wide studies of merkel cell carcinoma and validation of intratumoral CD8+ lymphocyte invasion as an independent predictor of survival". Journal of Clinical Oncology. 29 (12): 1539–46. doi:10.1200/JCO.2010.30.6308. PMC 3082974. PMID 21422430.

- ↑ Andea AA, Coit DG, Amin B, Busam KJ (November 2008). "Merkel cell carcinoma: histologic features and prognosis". Cancer. 113 (9): 2549–58. doi:10.1002/cncr.23874. PMID 18798233.

- ↑ Asgari MM, Sokil MM, Warton EM, Iyer J, Paulson KG, Nghiem P (July 2014). "Effect of host, tumor, diagnostic, and treatment variables on outcomes in a large cohort with Merkel cell carcinoma". JAMA Dermatology. 150 (7): 716–23. doi:10.1001/jamadermatol.2013.8116. PMC 4141075. PMID 24807619.

- 1 2 Paulson KG, Park SY, Vandeven NA, Lachance K, Thomas H, Chapuis AG, Harms KL, Thompson JA, Bhatia S, Stang A, Nghiem P (March 2018). "Merkel cell carcinoma: Current US incidence and projected increases based on changing demographics". Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 78 (3): 457–463.e2. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2017.10.028. PMC 5815902. PMID 29102486.

- ↑ Hodgson NC (January 2005). "Merkel cell carcinoma: changing incidence trends". Journal of Surgical Oncology. 89 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1002/jso.20167. PMID 15611998.

- ↑ Howard RA, Dores GM, Curtis RE, Anderson WF, Travis LB (August 2006). "Merkel cell carcinoma and multiple primary cancers". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 15 (8): 1545–9. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-05-0895. PMID 16896047.

- ↑ Clarke CA, Robbins HA, Tatalovich Z, Lynch CF, Pawlish KS, Finch JL, Hernandez BY, Fraumeni JF, Madeleine MM, Engels EA (February 2015). "Risk of merkel cell carcinoma after solid organ transplantation". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. 107 (2). doi:10.1093/jnci/dju382. PMC 4311175. PMID 25575645.

- ↑ Obituaries, The Daily Telegraph, London, UK, 11 June 2018, pg27

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- National Cancer Institute. "Merkel Cell Carcinoma". National Institutes of Health (US). Archived from the original on 2010-12-21. Retrieved 2011-01-20.